- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

A week has passed since Russian forces invaded Ukraine. The world has watched in horror as Europe’s second largest country has been blasted with a huge and lethal arsenal of weaponry. The

invaders have been denied victory by the astonishing feats of arms by Ukrainians: man for man they have outmatched their Russian foes in bravery and skill. Yet they are gradually yielding to

the superior force of a modern military despotism. In the south, the besieged port cities are being systematically reduced by massive artillery and missile bombardment. Kherson has fallen;

Mariupol probably cannot hold out much longer. The Russians intend to establish a coastal corridor, linking Crimea with Rostov, before advancing westwards to attack Odessa, Ukraine’s biggest

entrepôt and a tourist resort celebrated as “the jewel of the Black Sea”. To the east Kharkiv, though almost encircled and under heavy fire, is resisting fiercely. But it is only a few

miles from the border and, as Ukraine’s technology hub, a great prize for Putin’s war machine. Its mayor has warned the Russians that Kharkiv will be their new Stalingrad, but its older

citizens need no such comparisons: in the Second World War Kharkov, as it then was, suffered almost total destruction after being captured and recaptured twice in four ruinous urban battles.

If such a siege of Kharkiv has now begun, the fate of a million civilians still trapped there does not bear thinking about. Finally, what of Kyiv? It is the main focus of the Russian

onslaught, though all attempts to envelop the capital have thus far failed. The notorious “siege train” that has snaked its way south from Belarus has stalled while still some 20 miles from

the outskirts. The Ukrainian Army is mounting an effective defence on the ground, while its heroic pilots have denied Russia the complete control of the skies over the region necessary for a

full scale assault by land. But if in the coming days other offensives converge on Kyiv from the eastern and southern fronts, this city of nearly three million will be surrounded. With its

food supplies cut off and its ammunition running low, how long could Kyiv withstand the combined forces of the Russian armies? If the unthinkable took place and the capital were to fall,

would President Zelensky and his government be killed or forced to surrender? A Ukrainian government in exile would doubtless be formed, probably based in Poland, but the Russians would

treat the occupation of the rest of the country as a mopping up operation, using brute force to crush resistance and quite possibly deploying repressive measures not seen since Stalin’s

time. The Gulag Archipelago, as Solzhenitsyn called the vast network of Soviet forced labour camps and penal colonies, held up to 1.5 million prisoners at any one time from the late 1930s to

the early 1950s. Over nearly four decades some 18 million people passed through the system, of whom at least 1.5 million died as a direct result of the inhuman conditions. The Gulag was

dismantled by 1960 but has never been entirely abolished: Alexei Navalny is being held in one such penal colony. Putin would not hesitate to re-establish the Gulag to incarcerate any number

of recalcitrant Ukrainians. In case any reader thinks that this is far-fetched, numerous vehicles have already been observed near Kherson that appear to be ready for mass deportations.

Meanwhile, the humanitarian catastrophe that has already happened almost defies belief. In one week, according to the UN, a million Ukrainians have become refugees. More than half of these

people are being cared for in Poland and the burden will quickly become unsustainable for one country. Britain has already promised to take up to 200,000 extended family members of

Ukrainians already living here, but this is clearly not enough to deal with a rapidly evolving crisis, let alone to satisfy public sympathy for the plight of refugees. Because the UK very

seldom deports migrants, while London and the English language are magnetic attractions, the Home Office is rightly wary of allowing in unlimited numbers of undocumented refugees. But a

carefully calibrated scheme could be instituted in the coming days to allow us to shoulder our share of the exodus. Polls suggest that three quarters of the public want Britain to take

refugees without visas, though it is fair to assume that a much smaller proportion would be prepared to offer them accommodation in their own homes. But the fact that few people even

realised that there were already at least 70,000 Ukrainians living in the UK shows that they are quite used to integrating easily into a host country. The overall conclusion must be that,

now that the Russian Blitzkrieg has failed, the increasingly bitter and brutal war of attrition that has replaced it will get very much worse. How long is it likely to last? The best guess

must be: certainly weeks, probably months, possibly years. This war, like all wars, is partly a question of numbers. The statistics for refugees are fairly reliable, albeit constantly out of

date. The statistics for casualties, however, are still speculative and, especially on the Russian side, played down for propaganda reasons. Nevertheless, the numbers we have give much food

for thought. The Ukrainians say they have lost more than 2,000 civilian dead, though in conditions such as prevail in besieged cities accuracy is impossible. The true figure is bound to be

higher, quite possibly much higher, and will now be rising by hundreds every day. If the war in Ukraine were to continue at this level of intensity for the rest of this month, the civilian

death toll is likely to exceed the 30,000 killed in London over the six years of the Second World War — to give one meaningful British comparison. The military casualties are even harder to

interpret. Kyiv claims Ukrainians have killed at least 9,000 Russians, while Moscow admits to fewer than 500. Even the implausibly low estimate given by the Kremlin, however, is already a

worrying large number in the first week of what was claimed to be a limited “special operation” in the Donbas. If the true figure is much closer to the Ukrainian estimate, as seems likely,

then Russian forces have already lost about half as many men in a week as were killed in a decade of war in Afghanistan, a total of 15,000. The latter comparison is relevant because the

losses suffered in that ultimately abortive campaign played a key role in undermining the legitimacy of the Soviet leadership. Putin may imagine that he has avoided the mistakes of his

predecessors Gorbachev and Yeltsin. But it is beginning to look as if he learned the wrong lesson from Afghanistan. He evidently expected to occupy Kyiv as easily as the Taliban occupied

Kabul last year, and with just as anaemic a response from the West. Instead, he has embarked on an invasion that looks as foolhardy as that of 1979 — and with even more sanguinary

consequences for his own soldiers. Morale among the expeditionary forces in Ukraine appears to be low — reports abound of troops sabotaging their own equipment to avoid fighting — and on the

home front, too, apprehension seems to be turning into dismay. Police have already rounded up several thousand anti-war protesters, many of whom may be the usual suspects: students,

activists and dissident intellectuals. But now we are beginning to see a different cohort of demonstrators: elderly veterans of the “Great Patriotic War”, babushkas who cannot be dismissed

so easily by the authorities. Putin cannot afford to allow images of young men returning to their mothers in body bags on television, but Zelensky is broadcasting live Russian soldiers

appealing to their families from Ukrainian captivity. It will be interesting to find out what happens to such Russian prisoners if and when they are recaptured by their comrades. In the

Second World War, “liberated” Soviet POWs were either executed as traitors or at least sent to the Gulag on Stalin’s orders. A week after this war began, we know far more about both the

aggressors and their victims. The numbers of dead, wounded and displaced are known unknowns which will become clearer over time. The unknown unknown, however, is the mind of the dictator. We

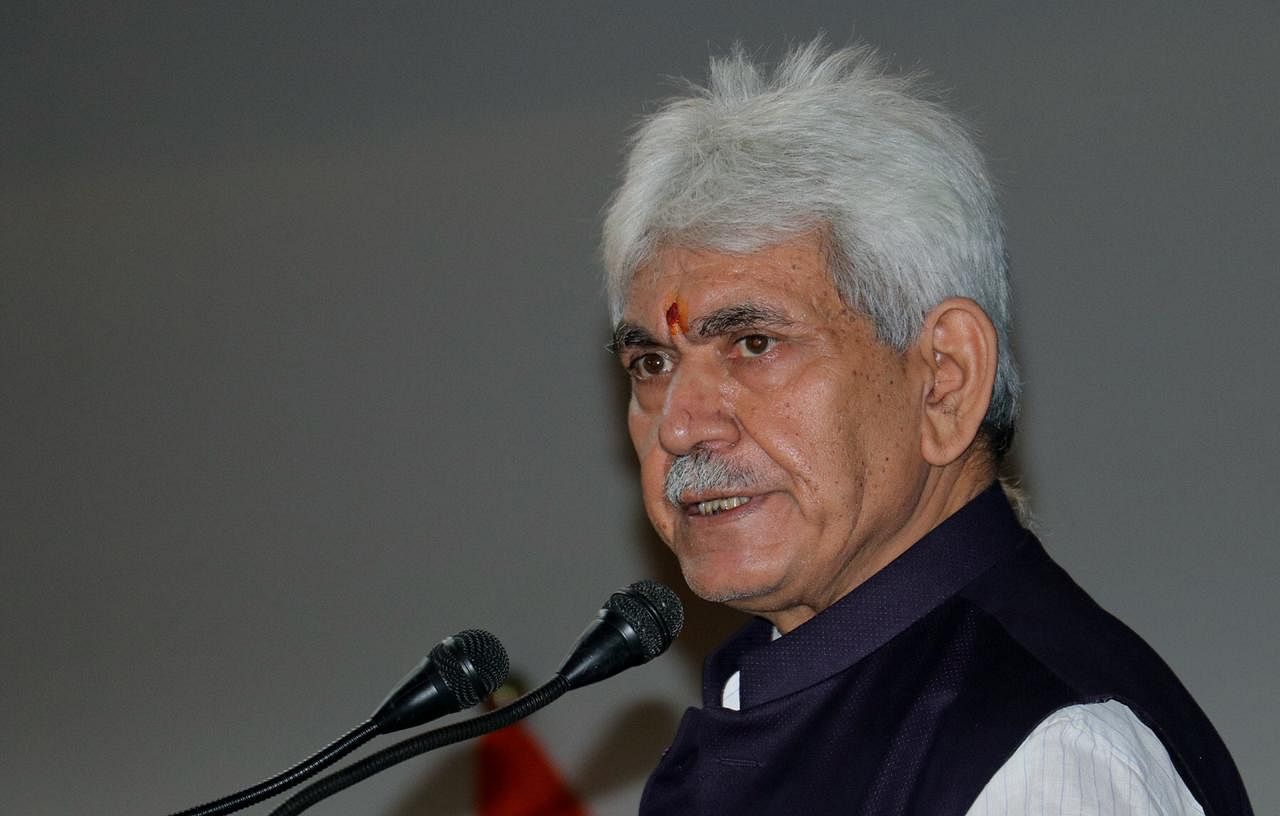

can psychoanalyse Vladimir Putin as much as we like, but the depths of his depravity remain unfathomable. Yet so much depends on his megalomania and detachment from reality. Unlike his

mortal enemy, Volodymyr Zelensky, Vladimir Putin has remained largely hidden from sight. His motives and purposes are even more occluded. All that can be said with certainty is that Putin is

now a desperate man, capable of almost anything except what is probably the only rational course: cutting his losses by withdrawing his troops. The West cannot risk a direct confrontation

with this nuclear-armed fanatic, but we can destroy his domestic credibility instead. An information war, to show the Russian nation that their leader is reducing their country to the status

of North Korea, might be the single most useful contribution that the democracies could make to his defeat. One way or another, Putin will fail — and then he will fall. But it would better

for all concerned if his own people were to remove him, rather than a palace coup. It will matter very much that one dictator should not be replaced by another, perhaps even worse. The best

way to prevent that happening would be for his troops to become bogged down, suffer heavy casualties and ultimately be left with no choice but to retreat from Ukraine. A MESSAGE FROM

THEARTICLE _We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever, and we need your help to

continue publishing throughout the pandemic. So please, make a donation._