- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

_Voilà un homme! _(“What a man!”) is how Napoleon enthused about Johann Wolfgang von Goethe at their meeting at Erfurt in 1808. Goethe reciprocated by recognising an irresistible daemonic

force in the Emperor. By then Napoleon had already read _The Sorrows of Young Werther_ seven times. He kept it under his pillow on campaign, much as Alexander the Great did with Homer’s

_Iliad_. Goethe’s achievements are almost uniquely multifarious. He has been described as “the prince of the mind” and also as the holder of the highest IQ and the largest vocabulary in

history. I once visited the Goethe Haus in Frankfurt and saw the great man’s enormous top hat. If cranial capacity were an indication of intellectual pre-eminence, then Goethe’s hat was

powerful surviving evidence. He was a poet, man of action, dramatist, _bon vivant_, a scientist who was fascinated by plants, minerals and optics (his “Theory of Colour” had the temerity to

disagree with Newton) a statesman, who rose to become Prime Minister of the then independent Principality of Weimar, sage, novelist and theatrical producer. In 1784 he discovered a bone in

the human body, hitherto unknown to science — the intermaxillary bone in the jaw. For five decades Goethe was European Literature. Contemporary sources provide the most eloquent

descriptions. In 1807, a court official wrote of Goethe: “He is tall of stature and gives an impression of slimness. The colour of his face is dark, almost like night. There is a certain

hardness in his features, which are, however, very alive. His eyes retain a hidden beam of light, shining the moment he smiles. I have seen him glow with warmth and heard the seething of the

riches within. I have recognised the lion by his claws.” His patron, the Duke of Weimar, said of him: “Goethe could drink terribly, he could match the best.” A colossal figure indeed, in

his appearance, his conspicuous consumption and in his creative work. In fact, it was Goethe’s essays on nature which inspired Sigmund Freud to take up the study of medicine. Goethe’s output

in his early years was imbued with a spirit of revolt against the political censorship and emotional constraints of the day. His _Werther_ novel, with the death of the young hero,

frustrated in love, swept Europe. Here for the first time in German literature, profound emotion and deep inner passion were exposed for all to see. This was _Sturm und Drang, _“storm and

stress”, later to reach its culmination in the romantic movement, engaging the full enthusiasm of the young, in a way that the straight-laced writings of the moribund late classical school

could no longer achieve. Riding this early romantic crest, Goethe’s play _Egmont _is a stirring tale of the liberation of the Netherlands from the autocratic Spanish Empire. The plot,

centring on the freedom of individual expression, inspired Beethoven to compose his own Egmont overture, a hymn of praise to liberation. The action of Egmont follows chronologically on from

that of Schiller’s play _Don Carlos_; one day, I hope, an enterprising theatre director will fuse them together as a double bill. The convenient thematic link would be the sinister Grand

Duke of Alba, the deadly opponent of Don Carlos in Schiller’s play and the executioner of Count Egmont in Goethe’s counterpart. Goethe’s oeuvre reinforced the sense of national identity

which Germany began to experience with Luther’s translation of the Bible (1520-1530) and which accelerated towards the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th. Goethe led this

resurgence with _Götz von Berlichingen _(1771). This was the work where Goethe described chess as the mind game “par excellence”, the _Probierstein des Gehirns _or “touchstone of the

intellect”. Goethe has become one of the standard-bearers of chess proselytism, proclaiming the value of the game to the world. Indeed, modern psychiatry confirms a definite link between

chess prowess and a very high IQ. As I mentioned here three weeks ago (June 24). this view has recently been endorsed by the Prime Minister. Rishi Sunak also wants pupils to continue to

study mathematics, until they leave school for university, employment or the dole. Personally, I believe that it would be more profitable to continue the study of Shakespeare than of maths.

Yet Shakespeare, though the brightest, was not the sole luminary in the pantheon of the literary genius of Elizabethan England. His chief rival for the laurels was Christopher Marlowe, whose

work was marked out by immense themes, giant characters and powerful blank verse. One such character was the oriental conqueror, Tamburlaine. (In fact Tamburlaine the Great Part Two,

contains my single favourite line in the whole of English literature: “Egregious viceroys of these Eastern parts!”) Tamburlaine was, incidentally, famed as a chess devotee, though, as befits

a megalomaniac world conqueror, he preferred to play on a much enlarged board (11×10 squares) with extra pieces, such as “camels” and “giraffes”. It is said that his son, Shah Rukh, was so

named, because Tamburlaine was moving a rook at the moment of his birth. A second archetypal Marlovian anti-hero was Dr. Faustus, an aged professor, a seeker after occult knowledge from the

depths of German myth, who bartered his soul to the Devil for twenty five years of guaranteed life and the fulfilment of all his earthly desires. It was a powerful story that took its theme

from the roots of western beliefs. It stretched back to the original challenge to God from the Garden of Eden, with its twin forbidden trees with their equally forbidden fruits of Knowledge

and Possession of Immortal Life. Goethe’s most ambitious project was to reclaim the Faust story from the English, who had appropriated one of Germany’s most potent myths, and re-forge it as

a harbinger of German identity and for a German audience. Even the sing-song, earthy verse form Goethe chose for his new epic of a man’s life, of a German Odyssey for a contemporary German

audience, harked back to the simple language of former times — in this case to the poetry of the shoemaker cum poet Hans Sachs, with its vigorous expression and humorous themes. Sachs was a

source who also attracted another German icon, Richard Wagner, in his _Meistersinger_. Goethe, whether he was consciously aware, or not, when he set out to write_ Faust_, ultimately

contributed to the unification of Germany through poetry. “Decide, and do it now, your actions clear as day. When you advance, then others flock your way. Without resolve, a million projects

fail. Commit right now, and let’s blaze history’s trail.” This was a gigantic task, and in the Prologue to his epic, from which the above words are taken, Goethe not only encourages

himself, but the whole incipient German nation, to get on with that task, a task which was rendered that much more imperative by Napoleon himself. With the French Emperor parcelling out and

repackaging Germany as he saw fit, and with England having purloined the natural material for a German national epic, the time had come for German nationalism to sweep to the fore. Within 39

years of the completion of Faust, Prussia and the remaining minor Germanic kingdoms had ceased to exist as disparate formal nation or city states and had been replaced by the homogenous

German Empire. Nowadays, even in Germany, Goethe’s original _Faust_ is largely confined to schools and universities, perhaps because of its extreme length, and appears to have been written

on dry, academic, official paper, as desiccated as anything in Faust’s own library. It is so easy to overlook the dynamic role Faust played in the creation of a new nation. Goethe’s _Faust

Part One _consists of 4,612 lines;_ Faust Part Two _is 7,498 lines, while both parts combined total 12,110 lines. In comparison, Sophocles’s _Oedipus Tyrannos_ is 1,500 lines, the

Anglo-Saxon heroic epic; _Beowulf_ is just over 3,182 lines, while _Hamlet_, Shakespeare’s longest play, is 4,042. Marlowe’s _Faustus_ is 2,197. It is at this point that I must confess a

personal interest. Having studied Goethe as my special paper at Trinity College, Cambridge, where I shared a landing for a year with our future King Charles III, I set myself the ambition of

one day translating Goethe’s _Faust_ into English. I am, therefore, delighted to announce that I have finished my translation into a version which I intend to be accessible for an English

speaking audience. The _Faust_ legend stems from medieval Germany, specifically the town of Wittenberg, where Luther in 1517 had nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Schlosskirche.

Shakespeare’s great rival, Christopher Marlowe, seized on the Faust story, this seeker after knowledge, who abjures his faith and strikes a pact with the Devil, signing away his soul in

words of blood. Marlowe’s _Tragical History of Dr. Faustus_ is one of the stellar works of the western literary cannon. Goethe saw hidden depths in the narrative and was determined to weld

an epic from it to equal those of Homer, Virgil, Dante and Milton. Goethe achieved this, as Virgil did with his hero Aeneas, or Homer with Odysseus, by creating the totality of the life of a

man and fleshing it out with multiple new dimensions. In contrast, Marlowe’s Faustus, as a man, is eloquent, defiant in his rejection of God, but ultimately a mere deceived and defeated

conjuror, who is condemned to an eternity of perdition. Marlowe’s Faustus loses his cosmic chess game against the Almighty, as, arguably does Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost, though in my

piece for _TheArticle_, I take the view that Satan comes out on top in his cosmic battle against _The Armipotent Deity. _ In Goethe’s _Faust_ the cosmic chess game takes place between Faust

and Mephistopheles. Just as the Devil appears to be triumphing, he accidentally snatches defeat from the jaws of victory, by misunderstanding Faust’s subtle use of the subjunctive. So, here

for the first time, I publish my performing version of Goethe’s Faust, so readers may observe for themselves how Mephistopheles is outmanoeuvred at the very end and at the mouth of Hell, by

_THE ANCIENT ONE, _as Mephistopheles refers to God in the Prologue in Heaven. Eighteen hundred years earlier, Virgil’s epic _The Aeneid_, provided for Rome the political, military, moral and

social justification, which bound Augustus’ new Empire together and conferred on it common identity and language, whilst simultaneously reinforcing its traditions. Virgil was thought to

possess vatic powers and was chosen by Dante over a millennium later to be his spiritual guide in his journey from the Divine Comedy to the Inferno and the _Purgatorio_. It is in the

celestial consummation, _The Paradiso,_ that Dante refers to the quasi-infinite numbers of corns doubling and redoubling on the squares of the chessboard, as reflecting the number of angels

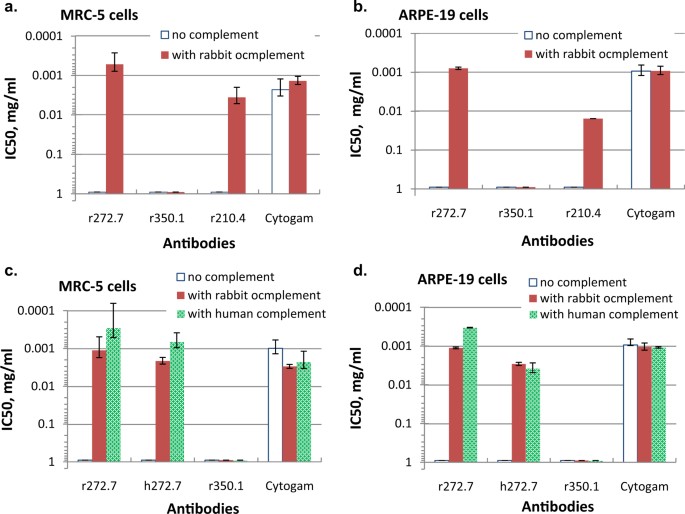

in the firmament. In the absence of any recorded games by Goethe, here are a few entertaining attacks by Schiller — Eric not Friedrich! Reshevsky vs. Schiller (Manhattan CC simul., 1972)

Schiller vs. Redman (University of Chicago Invitational, 1975) Schiller vs. Arne Foster City, 1995) Schiller vs. Collins (Gibraltar Masters, 2012) _Raymond Keene’s latest book “Fifty Shades

of Ray: Chess in the year of the Coronavirus”, containing some of his best pieces from TheArticle, is now available from _ _ Blackwell’s _ _. His 206th book, Chess in the Year of the King,

with a foreword by The Article contributor Patrick Heren, and written in collaboration with former Reuters chess correspondent, Adam Black, is in preparation. It will be published later this

year._ _ _ A MESSAGE FROM THEARTICLE _We are the only publication that’s committed to covering every angle. We have an important contribution to make, one that’s needed now more than ever,

and we need your help to continue publishing throughout these hard economic times. So please, make a donation._