- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

You may have noticed people talking about Marxism lately. [MARSHA BLACKBURN] …the unchecked spread of Marxist influence… [TOMMY TUBERVILLE] …as our nation has been taken over by the

Marxists… [LOUIE GOHMERT] …the demands of the anarchists and Marxists rampaging across America… [MARSHA BLACKBURN] …will threaten our very survival. [ELLIE] Okay, woah. Should I be

alarmed? The Marxists are threatening my survival? It seems like our elected officials are pretty worked up about this. But what does Marxism actually mean? Hi! I'm Ellie Anderson and

this is Crash Course Political Theory. [THEME MUSIC] “A spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of communism.” That’s literally the opening line to the “Communist Manifesto.” You can’t

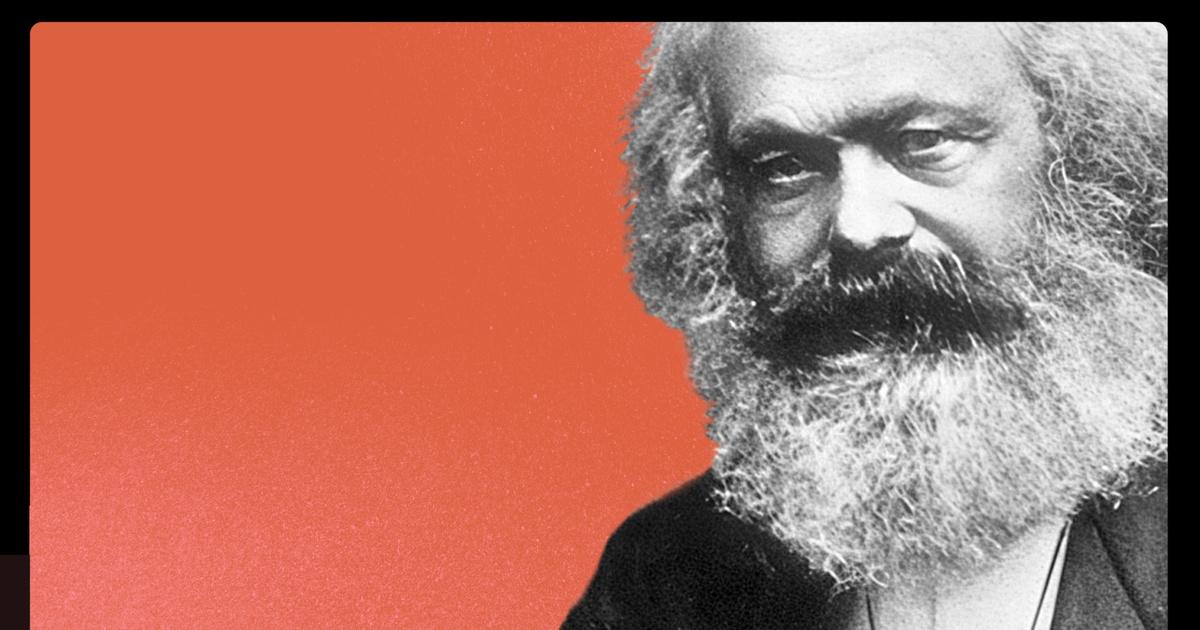

deny it’s a total banger. Ever since Marx and his co-author Friedrich Engels wrote this line in the late 1840s, people have agonized about the supposed evils of communism. In the 1950s,

Joseph McCarthy infamously made his political career rooting out alleged communists, coming for everyone from W.E.B Du Bois to Lucille Ball. And we’re still haunted by that ghost today. A

2024 bill would require high schools in New Hampshire to teach anti-communism. And in Florida, Republican lawmakers are trying to mandate anti-communist education from kindergarten up.

But, are Marx’s ideas really such a threat to freedom? Before I can answer that question, I have to back up into some very philosophical territory. I’m gonna need…a lot more coffee.

[jazzy music plays] [sighs] Okay. Bear with me while I attempt to explain a concept that’s a tough one even for philosophy grad students: dialectical materialism. I know, even the name

sounds scary. But we are in this together. Let's do it. So Karl Marx was a fan of German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel, who had this theory about how ideas evolve. Basically, he thought

that any general way you think about the world— any philosophy, model, or theory— isn’t one solid idea, but rather the result of a bunch of contradictory perspectives in conflict with each

other. And as people try to reconcile their opposing viewpoints, they create new ideas—an ongoing process he called the “dialectic” —think “dia” like dialogue, “lectic” like lecture: two

conflicting ideas talking, and eventually synthesizing into new ones. Still with me? Okay. Now, in Hegel’s view, if you want to understand why the world is the way it is, you have to look to

the realm of ideas. A perspective called idealism. But Marx turned Hegel on his head. He said, if you want to understand why the world is the way it is, you have to look not at ideas, but

at the physical world. The material conditions of the world, especially the economic ones. This is called materialism. So, want to understand why religion is the way it is? You need to

understand wages. Want to understand why a society has the moral values it does? You need to look at the market. In other words, in Marx’s view, material economic systems are the root of

everything. Not just how goods are exchanged, but who controls what gets made, who actually makes the things, the conditions they’re under, and so on. As he put it, “every class struggle is

a political struggle.” And when we put these two big ideas together — the dialectic and materialism — we get a view called dialectical materialism. I know, great name. This is Marx’s real

bread and butter. It’s the view that once we understand the world in terms of its material, economic realities, we can better understand how history works — how things change over time. And

much like what would happen if you gave a roomful of hungry grad students a single sandwich, conflict is inevitable. So, most of what Marx talked about were problems with capitalism. And in

contemporary American society, many people associate critiques of capitalism with communism. Which explains why a lot of people today think of Marx as the spokesperson for communism. Well,

that and the fact that he co-authored a pamphlet called the “Communist Manifesto.” Which if you don’t want to be associated with communism is just bad branding. But hindsight is 20/20. In

reality, Marx didn’t actually write very much about what a communist government might look like. But he did have a lot to say about the problems with capitalism, including these three hot

takes: First, Marx believed that humans are productive by nature-- an idea called homo faber. Homo…human. Faber…fabricate. People make stuff; it’s what we do. But not just for creativity’s

sake; we control our environment through the use of tools, and according to Marx, we get our sense of self partly from seeing the impact of our work on the world. If that’s true, then

making stuff and not seeing the impact is going to really screw people up. Hot take number two. Under a capitalist system, workers make stuff to get money… and that’s all they get. The

person who owns the factory gets all the extra value created by that work— what we would call the profit. And when the worker is doing all this life-affirming labor just to make more profit

for the dude at the top, she feels estranged, not only from the things she makes but even from the work, from herself, and even from her fellow homo fabers. This is what Marx called

alienation. And finally, there’s the cash workers get for their labor—it’s not much. In a capitalist system, Marx said, workers compete with each other to accept the lowest pay. Meanwhile,

capitalists compete with each other to pay the least while producing the most. If a worker demands a higher wage, they’ll be out of a job. The whole system, Marx thought, was built on

exploitation. All this alienation and exploitation leaves me wondering: has anyone ever tried to do it differently? Turns out, yeah. Let’s head to the tape… [TV static] Mondragon, the

world’s largest existing worker-owned cooperative, emerged in 1956, when a Spanish priest named José María Arizmendiarrieta was assigned to an impoverished town in the Basque region of

northern Spain. He started a technical school and helped workers get their engineering degrees, and then the workers started leaving the factory to launch their own cooperatively owned

companies. In a worker-owned co-op, there’s no capitalist at the top scraping off the profit for themselves. The business is owned by the workers — and when a profit is made, the workers

share it. The co-ops grew, and grew, and grew… into the Mondragon Corporation, a group of over ninety cooperatives— including a grocery chain, a consulting firm, and a bike manufacturer.

At Mondragon, all the worker-owners vote on big decisions like strategy and salaries. The highest-paid executive makes, at most, six times the salary of its lowest-paid worker. That might

sound like a lot, but to put it into perspective, American CEOs are paid, on average, three hundred and forty-four times as much as typical workers. [into earpiece] You’re sure that’s

not a typo? Nope? Okay. Still, Mondragon exists within a broader capitalist system. Which means they have to compete with non-worker-owned competitors— so they do things like outsource

production to factories in cheaper markets, whose workers don’t own the means of production. OK, so Mondragon isn’t perfect, but it offers an alternative to some of the problems Marx had

with capitalism. Because, crucially, Marx didn’t think that a bunch of exploited and unfulfilled workers would just put up with it forever. And here’s where Marx’s view of dialectical

materialism and his thinking about capitalism come together. See, as I mentioned, at its core, dialectical materialism is a perspective on how history works. To Marx, he was explaining

something inevitable: a cause and effect. Like a science experiment. And if the material reality that people were living under was capitalism — if that was the cause — Marx thought there was

only one possible effect. The proletarian revolution. These alienated, unhappy workers—the proletariat —would attack the means of production. They’d take down the actual factories. Here’s

how Marx thought it would go down. First, the workers would organize once they recognized their power. They’d form trade unions to combine efforts. There would be walkouts! Strikes! Picket

lines! And finally, the united workers would become a political party and seize the means of production. Capitalists would no longer own the factories or exploit the workers. Workers would

collectively control it all. And here’s the thing. Marx believed this was absolutely inevitable, almost like the laws of physics. But instead like — the laws of history. Because he believed

capitalism was inherently unsustainable. Its internal contradictions would lead to a dialectical shift where it would eventually bring about its own demise. But he didn’t say when this

would happen, which is a source of contention among Marxists. Hey guys, where are you going? Wait, is it happening right now? False alarm. Anyway, turn on the news today and you’re likely to

hear people still talking about Marx centuries later. And often in a… pretty negative way. [Ominous music] But other people think he did at least get some things right. I mean, it seems to

me that a lot of Marx’s predictions about capitalism have come true. For instance, he predicted there would be increasingly rampant income inequality. And look at this: in 2023, the

bottom fifty percent of earners in the US held less than three percent of all household wealth. While the top ten percent? They held over sixty percent. But can we really boil down all

struggle to class struggle? What about racism, sexism, or homophobia? Would giving power to the working class really solve all those problems? These questions have led some critics to

believe that Marx is way overhyped. They’d argue that class isn’t the most important thing to consider—race and gender are. And then there are folks who lie somewhere in the middle, who may

consider themselves Marxists but don’t think he had all the pieces in place. Many contemporary Marxist perspectives recognize that class does matter, but that other aspects of identity

impact people’s lives in overlapping and complex ways. Intersectionality considers how race, gender, sexual orientation, class, and other social identities affect each other. There’s more

on intersectionality in Crash Course Sociology. The point is, Marx didn’t consider different kinds of discrimination and identity perspectives in his theories —but modern Marxists can,

and often do. And what about Marx’s concept of alienation? Is that really a capitalist problem—or simply a human one? Some claim that we can ease our alienation through socialist practices

like worker co-ops. That way, we can get the benefits without chopping capitalism to bits. But as we saw with Mondragón, there are limitations there too. We also don’t know how much more

alienation we’ll have to experience before the proletarian revolution happens. Unless… [into ear piece] Really guys? It’s happening again? Nope. Anyway, the thing about Marx is, we’re

still talking about him. No matter what we think about his theories and ideas, you can’t deny they had an impact. This old German philosopher’s name is still in the mouths of right-wing

pundits and socialist activists alike, thrown around as a political buzzword to ruffle feathers. But by understanding what Marx really had to say, and where his ideas came from, we can have

a more productive conversation about what is and isn’t working in our current system, how class and other aspects of identity affect our lives, and what we can expect for the future.

Next time, we’ll ask if anarchism is really the dystopian nightmare it’s been made out to be.