- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

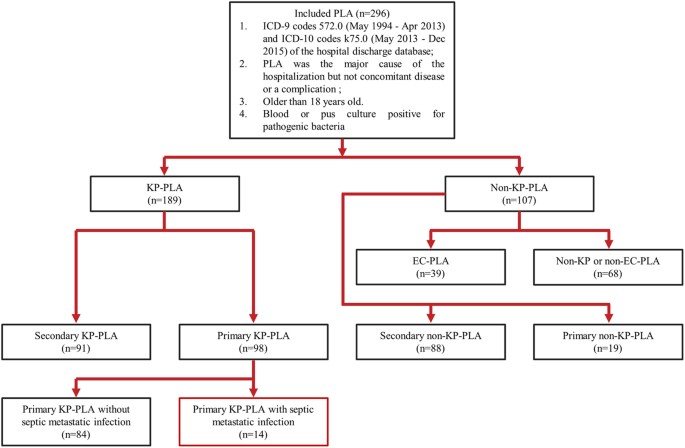

ABSTRACT Spontaneous isopeptide bond formation, a stabilizing posttranslational modification that can be found in gram-positive bacterial cell surface proteins, has previously been used to

develop a peptide-peptide ligation technology that enables the polymerization of tagged-proteins catalyzed by SpyLigase. Here we adapted this technology to establish a novel modular antibody

labeling approach which is based on isopeptide bond formation between two recognition peptides, SpyTag and KTag. Our labeling strategy allows the attachment of a reporting cargo of interest

to an antibody scaffold by fusing it chemically to KTag, available via semi-automated solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), while equipping the antibody with SpyTag. This strategy was

successfully used to engineer site-specific antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) that exhibit cytotoxicities in the subnanomolar range. Our approach may lead to a new class of antibody conjugates

based on peptide-tags that have minimal effects on protein structure and function, thus expanding the toolbox of site-specific antibody conjugation. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS

THE RENAISSANCE OF CHEMICALLY GENERATED BISPECIFIC ANTIBODIES Article 19 January 2021 SPYMASK ENABLES COMBINATORIAL ASSEMBLY OF BISPECIFIC BINDERS Article Open access 16 March 2024

GENERATING A MIRROR-IMAGE MONOBODY TARGETING MCP-1 VIA TRAP DISPLAY AND CHEMICAL PROTEIN SYNTHESIS Article Open access 23 December 2024 INTRODUCTION The conjugation of small molecule drugs

to antibodies represents a promising strategy for the development of cancer therapeutics. By harnessing the capacity of antibodies to home in on specific targets and combining that with the

cytotoxic capability of small molecule drugs, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) can be generated to deliver lethal payloads to cancer cells with precision, while minimizing the off-target

effects of cytotoxic drugs to increase the therapeutic index1. First generation ADCs employing statistic conjugation of cytotoxic payloads via reduced cysteines or lysines led to

heterogenous populations with limited therapeutic index suffering from a low efficacy and inconsistent _in vivo_ performance2,3. Initial attempts to generate homogenous ADCs with a defined

stoichiometry relied on the mutation of selected interchain cysteines to serines and conjugation of the cytotoxic payload to the remaining accessible cysteines originating from reduction4.

Since then, several elegant methods have been developed to conjugate drugs to antibodies in a site-specific manner5,6. Chemical methods include the site-specific chemical conjugation through

engineered cysteines7 or selenocysteines8,9, cysteine containing tag with perfluoroaromatic reagents10 and conjugation to reduced intermolecular disulfides by re-bridging

dibromomalemides11, bis-sulfone reagents12, and dibromopyridazinediones13. In addition, several enzymatic and chemoenzymatic conjugation approaches have been reported including the use of

engineered galactosyl- and sialyltransferases14, formyl glycine generating enzyme (FGE)15, phosphopantetheinyl transferases (PPTases)16, sortase A17, and microbial transglutaminase18,19,20,

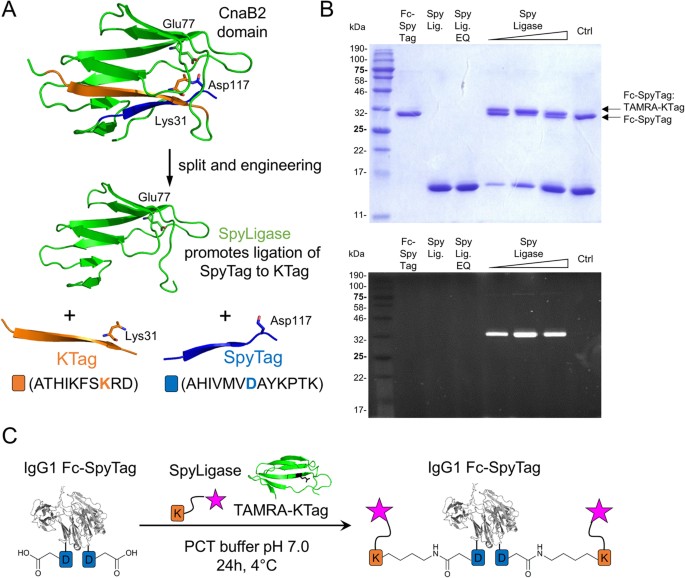

an enzyme forming an isopeptide bond between a glutamine side-chain and an amine-donor substrate. Here we sought to explore a new method for engineering ADCs. Spontaneously forming

intramolecular isopeptide bonds—peptide bonds that form outside of the protein main chain—were first discovered a decade ago and were found to provide remarkable stability to outer-membrane

proteins of Gram-positive bacteria21. Using these protein scaffolds, Zakeri _et al_. engineered a series of genetically programmable peptide-protein partners that are able to spontaneously

reconstitute via covalent and irreversible isopeptide bond formation22,23. One of these peptide-protein partners was obtained by engineering and splitting the _C_-terminal beta-strand of the

CnaB2 domain from the fibronectin adhesion protein FbaB of _Streptococcus pyogenes_ that is able to reconstitute with the protein by forming an intramolecular isopeptide bond between an

aspartate and a lysine residue catalyzed by an opposed glutamate22. Further engineering of the CnaB2 domain and splitting it into three parts generated the synthetic enzyme SpyLigase that is

able to direct the formation of an isopeptide bond between the two peptides SpyTag and KTag (Fig. 1A)24. Since the tags can be genetically fused to various proteins, these protein

superglues have emerged as useful tools to covalently and specifically assemble linear and branched protein structures, thereby enabling the generation of new protein architectures via

modular assembly25. RESULTS EXPRESSION OF PEPTIDE-TAGGED IGG1 ANTIBODY FC DOMAINS, SPYLIGASE AND SYNTHESIS OF LABELED PEPTIDES To test whether the SpyLigase-catalyzed peptide ligation

approach could also be applied for the covalent attachment of small reporting molecules such as fluorescent dyes, biotin or cytotoxins to antibody scaffolds, we fused SpyTag (13aa) and KTag

(10aa) genetically to the _C_-terminus of an Fc domain from an IgG1 antibody via a short GS-linker. In order to facilitate analysis of conjugates, an N297A mutation was introduced into the

IgG1-Fc gene by site-directed mutagenesis to remove the natural glycosylation site. The peptide-tagged antibody fragments were transiently expressed in HEK293F cells and subsequently

purified by protein A affinity chromatography. SpyTag and KTag-peptides with adjacent _N_-terminal GSG-spacer were synthesized on solid support by semi-automated SPPS using a Rink amide

(RAM) resin yielding peptide carboxamides after cleavage. KTag was further extended with a GY-dipeptide at the carboxy terminus as described24. 5/6-Carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA), a

fluorophore commonly used for the preparation of protein conjugates, and biotin were coupled to the resin-bound peptide amino terminus via standard amide coupling chemistry using

2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA). After cleavage from the resin, labeled peptides were purified by

semi-preparative RP-HPLC and analyzed by ESI-MS. SpyLigase and its inactive mutant SpyLigase EQ were obtained in yields of 20 mg per liter by expression in _Escherichia coli_ and

purification by affinity chromatography followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC)24. The purity of the proteins was >95% as determined by denaturing SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis

(Fig. 1B, upper panel, and S1, lane 2–4). CONJUGATION OF LABELED PEPTIDES TO ANTIBODY FC DOMAINS BY SPYLIGASE-MEDIATED ISOPEPTIDE BOND FORMATION We next performed conjugation reactions of

labeled-peptides to the peptide-tagged Fc domains at pH 7.0 in the presence of the protein stabilizer trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) for 18–24 h at 4 °C. Each reaction contained

peptide-tagged IgG1-Fc, labeled peptide counterpart (20 eq.), and SpyLigase (1–10 eq.). All possible combinations of SpyTag and KTag with the respective TAMRA or biotin labeled counterpart

were assayed. Covalent ligation reactions were analyzed by boiling the samples for 5 min in SDS-loading buffer and subsequent SDS-PAGE analysis. Reaction products were visualized by

Coomassie staining, fluorescence readout or western blotting (not shown). For all combinations the formation of a new product, stable to boiling in SDS, with a slightly slower migration

behavior consistent with isopeptide bond formation between SpyTag and KTag was observed (Fig. 1B, upper panel, and S1, lane 5–7). This product was not observed when SpyLigase was replaced by

its inactive Glu77 to Gln mutant (SpyLigase EQ). This mutant was not able to catalyze the spontaneous isopeptide bond formation due to the lack of the required glutamate residue (Fig. 1B,

upper panel, and S1, lane 8). These results suggested that SpyLigase covalently links KTag and SpyTag in a site-specific manner. The conjugation efficiencies for Fc-SpyTag with TAMRA-KTag

were estimated to be 40–60%. Here, reactions with three equivalents of SpyLigase seemed to be most efficient (Fig. 1B, upper panel, lane 6). Conjugation of the Fc-KTag with TAMRA-SpyTag was

observed to be less efficient, which may be caused by a shorter GS-linker that was used to fuse KTag to the Fc (Figure S1 lane 5–7). SPYLIGASE-MEDIATED CONJUGATION OF LABELED PEPTIDES TO

SPY-TAGGED ANTIBODIES Having proven our site-specific labeling approach on antibody domains, we extended the application for the preparation of defined antibody conjugates of the anti-EGFR

monoclonal antibody cetuximab (Erbitux®). The cetuximab fusion proteins with SpyTag at the _C_-terminus of the heavy chains, the light chains, and at both chains were obtained by expression

in HEK293F cells and purified by protein A affinity chromatography. The yields were comparable to those obtained for the unmodified antibody (40–60 mg per liter cell culture). SEC analysis

revealed no significant aggregation behavior of the peptide-tagged antibodies (Figure S2). Antibodies were then conjugated to TAMRA-KTag using SpyLigase under previously determined reaction

conditions. Reaction products were analyzed by in-gel fluorescence and Coomassie staining following SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis. Fluorescent bands corresponding to the conjugated antibody’s

heavy and light chains and a mobility shift of the conjugated light chain confirmed that SpyLigase-promoted site-specific labeling can also be applied on full-length IgG1-antibodies (Figure

S3, lane 2–4). These results indicated a chemically highly specific conjugation reaction due to the required assembling of SpyTag/KTag and SpyLigase to form an active complex mediating

isopeptide bond formation. SYNTHESIS OF CYTOTOXIN-PEPTIDE PAYLOADS AND CONJUGATION TO SPY-TAGGED ANTIBODIES Next, we wanted to investigate whether SpyLigase-catalyzed conjugation could also

be applied for the coupling of drug molecules to antibodies to generate site-specific ADCs. For this purpose, we designed and synthesized a set of Monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE)-peptide

payloads differing in the nature of the used linker and the chemistry used for peptide-coupling (Fig. 2, compound 5–7). MMAE was designed with either a non-cleavable (nc) maleimide-thiol

linker (compound 5), without linker (compound 6), or with a cleavable valine-citrulline-_p_-aminobenzylcarbamate (vc-PABC) linker7,26,27 (compound 7). In general, all payloads contained

polyethylene glycol (PEG) spacer-units to increase the overall toxin solubility and to increase the toxin-peptide distance. To persue two different chemical strategies, toxins were either

provided with an azide functionality for copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) or with an carboxyl group for amide coupling. For peptide-toxin coupling in solution by CuAAC,

resin-bound KTag was first coupled to propargylacetic acid to obtain an _N_-terminal alkyne moiety before it was cleaved from the resin and purified. The carboxy functionalized MMAE was

coupled directly to the _N_-terminus of the resin-bound peptide, requiring an acidic cleavage step of the entire MMAE-payload. As a proof of principle, cetuximab fused to SpyTag at the heavy

chains was used for conjugation. These reactions were carried out in phosphate-citrate buffer pH 7.0 in the presence of TMAO for 18–24 h at 4 °C. Each reaction contained Spy-tagged

antibody, 15 eq. of the toxic payload, and 3 eq. of SpyLigase. Reactions were analyzed by hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) and drug-to-antibody ratios (DAR) were determined.

Using payload 5, the highest observable DAR was only 0.57 (Figure S4). With the payloads from peptide-coupling via click-chemistry, formation of about 80% of the desired species with two

drug molecules was obtained, resulting in a DAR of 1.76 for payload 5 and a DAR of 1.66 for 7. Control reactions with either SpyLigase EQ, without SpyLigase, and without payload did not

result in the formation of a new product. This was analyzed by HIC, confirming also the specificity of the reaction (Figure S5). MS ANALYSIS OF SPY-TAGGED ADCS Next, we confirmed the

identity of the peptide-tagged ADCs and the specificity of the conjugation reaction by mass spectrometry. Intact mass analysis of ADCs by MALDI-MS indicated the attachment of two payload

molecules per antibody by a mass shift of 5252 Da (calc. 5349 Da) for payload 6 and 6202 Da (calc. 6159 Da) for payload 7 (Figure S7) compared to unmodified Spy-tagged cetuximab. This

observation was verified by mass analysis of reduced ADCs showing a mass shift of 2735 Da (calc. 2675 Da) and 3116 Da (calc. 3080 Da) for payload 6 and 7, respectively (Figure S8). In order

to confirm the identity of the ADCs, a more accurate mass determination was obtained by LC-ESI-MS showing a mass shift of 2677 Da for compound 6 (calc. 2675 Da) (Figure S9). Tryptic

digestion of the ADCs resulted in a peptide fragment composed of amino acids derived from both SpyTag and KTag which are connected to each other via an isopeptide bond between Asp and Lys

residues (Figure S13). This fragment was successfully identified in both ADC samples but not in the unconjugated antibody control. Further identification of the peptide was conducted by

sequencing using Tandem-MS (Figures S14–S16). Unmodified SpyTag fragment, however, was only observed in minor amounts confirming the efficiency of our approach (Figure S17). No unspecific

conjugation of the antibody light chain was observed (Figure S18). _IN VITRO_ CYTOTOXICITY OF SPY-TAGGED ADCS To determine the cell killing activities of the Spy-tagged cetuximab-based ADCs

_in vitro_, ligation reactions were scaled up and ADCs were purified by protein A chromatography in order to remove excess payload and SpyLigase. _In vitro_ cytotoxicity was determined using

two different breast cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-468 and MCF-7, the former one expressing high levels of EGFR (epidermal grow factor receptor, EGFR+), the latter one without EGFR expression

(EGFR-)28. ADCs with payloads that were synthesized by CuAAC with either non-cleavable linker (compound 6) or with cleavable linker (compound 7) were compared to each other to investigate an

effect of the different linkers on efficacy and potency. The ADCs were tested in a serial dilution with the highest concentration of 50 nM for three days. As expected, cetuximab-based ADCs

effect on MDA-MB-468 cells in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 3, upper panels). For the ADC with a non-cleavable linker the half-maximal cytotoxic effect was in the subnanomolar range (IC50 =

0.2 nM) (Fig. 3A, ■). In contrast the ADC with a cleavable linker showed an even higher _in vitro_ potency (IC50 = 0.1 nM) (Fig. 3B, □) which was probably due to the cathepsin B-mediated

cleavage of the linker in the lysosome releasing the free toxin upon cellular uptake. No effect on cell viability was observed with the same ADCs on the EGFR-negative cell line MCF-7 (Figure

3, lower panels). To confirm the receptor-mediated internalization and cell killing of the anti-EGFR ADCs, anti HER2 (human epidermal grow factor receptor 2) Spy-tagged trastuzumab ADCs

were prepared with the same payloads under identical reaction conditions and tested as isotype controls. The free payload was also used as control. MDA-MB-468 cells do not express HER2

whereas MCF-7 cells exhibit a low expression of HER228. The cell viability of both cell lines was not affected by the isotype control ADCs (Fig. 3, ○ and ●), demonstrating that the anti-EGFR

ADCs generated by using the catalytic activity of SpyLigase selectively kill EGFR-overexpressing cells in a receptor-dependent manner. A cell killing effect of free payload 7 was observed

at the highest concentration of 50 nM (Fig. 3B, ▲). CONCLUSION In conclusion, we have developed a modular bioconjugation approach based on isopeptide bond formation between two peptide tags

catalyzed by SpyLigase. This approach was used as a tool for the site-specific conjugation of small reporting molecules like fluorescent TAMRA and biotin to antibodies and for the generation

of homogenous ADCs. ADCs prepared by fusing SpyTag to the _C_-terminus of the anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab and attaching a cytotoxic compound to the chemically synthesized KTag

were characterized regarding their biophysical and cytotoxic properties _in vitro_. The obtained ADCs performed specifically and were observed to exhibit subnanomolar IC50 values. We assume

that this technology can also be used for engineering ADCs with a higher payload density since it has been described that the used peptide tags were also reactive when placed at internal

sites of a protein24. The feasibility of such a peptide-tagged ADC approach has recently been proven by the introduction of small substrate sequences for enzyme-promoted conjugation at

different constant region loops positions of trastuzumab for efficient site-specific ADC preparation16. The possibility to place the peptide-tags at multiple sites within the antibody

scaffold would clearly provide an advantage compared to covalent peptide labeling via sortases that exclusively allow for _C_-terminal payload conjugation17,29,30,31. In addition to

microbial transglutaminase our approach offers the opportunity for site-specific and efficient antibody conjugation based on a stable isopeptide bond. METHODS EXPRESSION AND PURIFICATION OF

SPYLIGASE The plasmid coding for SpyLigase (pDEST14-SpyLigase) was purchased from Addgene (Addgene ID 51722). The plasmid coding for the inactive form of SpyLigase (pDEST14-SpyLigase EQ) was

generated by Quick Change Side-Directed Mutagenesis by introducing an E77Q mutation according to the literature22,24. SpyLigase expression in _E. coli_ BL21 DE3 pLysS (Stratagene) and

purification via immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) was conducted according to the literature22,24. After dialyzing proteins in a 1,000-fold excess of PBS overnight at 4

°C, size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) was performed using a HiPrep (16/60) Sephacryl S-200 HR column (GE Healthcare) and PBS. Proteins were concentrated by centrifugation dialysis using

Amicon Ultra-15 (Merck Millipore, NMWL 3000 Da) and protein concentrations determined at 280 nm using a nano spectrophotometer (MW = 11474.3 g/mol, ε280 = 15930 M−1m−1). A protein yield of

about 20 mg per liter culture could be obtained. Proteins were supplemented with 10% (v/v) glycerol, aliquots frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. EXPRESSION AND PURIFICATION OF

IGG1 FC AND ANTIBODIES FUSED TO PEPTIDE TAGS IgG1 Fc (pEXPR-IgG1 Fc) was fused to either SpyTag (AHIVMVDAYKPTK) or KTag (ATHIKFSKRD) with additional GY-dipeptide at the _C_-terminus by using

standard molecular cloning techniques. Native IgG1 glycosylation at position N297 was eliminated by introducing a N297A mutation by Quick Change Side-Directed Mutagenesis. Plasmids coding

for chimeric cetuximab (C225, Erbitux®) and trastuzumab (Herceptin®) were kindly provided by Merck KGaA (Darmstadt). Cetuximab and trastuzumab variants containing SpyTag at the _C_-terminus

of either the heavy chains, the light chains, or at both chains were prepared by standard molecular cloning techniques. A (GSG)2-linker was introduced between the _C_-terminus of the

antibody and SpyTag. IgG1 Fc and full-length antibodies were transiently expressed from HEK293F cells using the Expi293 Expression System (Life Technologies). Supernatants containing

secreted proteins were conditioned and applied to spin columns with PROSEP-A Media (Montage, Merck Millipore). Columns were washed with 1.5 M Glycine/NaOH, 3 M NaCl, pH 9.0 and proteins

eluted with 0.2 M Glycine/HCl pH 2.5 into 1 M Tris/HCl pH 9.0. Eluted proteins were dialyzed in 1 × DPBS (Life Technologies) using Amicon Ultra-15 (Merck Millipore, NMWL 10000 Da) and stored

at 4 °C. CONJUGATION OF PEPTIDE-TAGGED IGG1 FC Antibody fragments (IgG1 Fc) fused to either SpyTag or KTag at the _C_-terminus were mixed at 5 μM with 50 μM of TAMRA-KTag or TAMRA-SpyTag,

respectively, and incubated in the presence of 5–50 μM of SpyLigase (1–10 mol eq.) for 24 h in 40 mM Na2HPO4, 20 mM citric acid buffer, pH 5.0, with addition of 1.5 M trimethylamine N-oxide

(Sigma-Aldrich) to give a final pH of 7.0 (PCT buffer) at 4 °C. Control reactions using 50 μM of an inactive SpyLigase (EQ, E77Q) were performed simultaneously. Reactions were stopped by the

addition of SDS loading buffer and samples heated at 95 °C for 5 min. SDS-PAGE was performed on 15% polyacrylamide gels at 40 mA for approximately 45 min. Gels were analyzed by fluorescence

readout using a Versa Doc Imaging System 5000 (Bio-Rad) and afterwards stained with Coomassie Blue. SPYLIGASE-MEDIATED ANTIBODY CONJUGATION Cetuximab or trastuzumab fused to SpyTag at the

_C_-terminus of the heavy chain, light chain, or at both chains was mixed at 6 μM with 120 μM of TAMRA-KTag and incubated in the presence of 18 μM of SpyLigase for 24 h in 40 mM Na2HPO4, 20

mM citric acid buffer, pH 5.0, with addition of 1.5 M trimethylamine N-oxide (Sigma-Aldrich) to give a final pH of 7.0 at 4 °C (PCT buffer). Antibodies conjugated to TAMRA-KTag were analyzed

by SDS-PAGE on 15% polyacrylamide gels and fluorescently labeled heavy and/or light chains visualized by fluorescence readout using a Versa Doc Imaging System 5000 (Bio-Rad). For toxin

conjugations, cetuximab or trastuzumab fused to SpyTag at the _C_-terminus of the heavy chain was incubated at 6 μM with 90 μM of the respective MMAE-KTag payload and incubated in the

presence of 18 μM of SpyLigase under the above described reaction conditions. Antibody drug conjugates were evaluated by hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) on a TSKgel Butyl-NPR

column (Tosoh Bioscience, 4.6 mm x 3.5 cm, 2.5 μm) using an Agilent Infinity 1260 HPLC. The HIC method was applied using a mobile phase of 1.5 M (NH4)2SO2, 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 (Buffer A)

and 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 (Buffer B). ADCs (45 μg) in 0.75 M (NH4)2SO2 were loaded and eluted with a gradient consisting of 2.5 min 0% Buffer B followed by a linear gradient into 100% Buffer

B over 35 min with a flow rate of 0.9 ml/min. For preparative ADC preparations, reactions were scaled up and ADCs purified by protein A magnetic beads (Promega) according to the

manufacturers protocol. Excess payload and SpyLigase were removed by rigorous washing with PBS before eluting ADCs with 100 mM citrate buffer pH 3.0 into 1 M Tris-HCl pH 9.0 neutralization

buffer. ADCs were buffered into PBS by using PD MiniTrap G-25 colums and concentrated by centrifugation dialysis (100 K Amicon Ultra 0.5 Centrifugal Filters). _IN VITRO_ CYTOTOXICITY OF

PEPTIDE-TAGGED ADCS _In vitro_ cytotoxicity of peptide-tagged anti EGFR ADCs was determined by using MDA-MB-468 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells. MDA-MB-468 cells have a high EGFR expression

level, but no HER2 expression28. MCF-7 cells show no EGFR expression, but a weak HER2 expression28. Cells were cultivated in appropriate culture media according to the manufacturer protocol.

Cells were detached by trypsination, diluted and allowed to settle down in 96-well plates at a seeding density 12.5 × 104 cells/ml (0.08 ml/well) for 24 h at 37 °C (5% CO2). ADCs and free

payloads were diluted in appropriate culture media and added to the cells in various concentrations (ranging from 50 nM to 7.6 pM) following a three-day incubation at 37 °C (5% CO2). All

concentrations were assayed in duplicates. Cell proliferation was determined by adding CellTiter-Glo (Promega) and luminescence readout (Synergy 5, BioTek). GENERAL FOR PEPTIDE CHEMISTRY All

chemicals and solvents for peptide synthesis, analysis, and isolation were purchased from Iris Biotech, Agilent Technologies, Sigma-Aldrich, or Roth and used without any further

purification. MMAE-linker payloads were obtained from Syngene. PEPTIDE SOLID-PHASE SYNTHESIS Peptides were synthesized at a 0.1 mmol scale on an AmphiSpheres 40 RAM resin (Agilent, 0.37

mmol/g) by microwave-assisted Fmoc-SPPS using a Liberty BlueTM Microwave Peptide Synthesizer. Activation of the respective carboxyfunctional amino acid (0.2 M) was performed by 1 M Oxyma/0.5

M _N,N_′-Diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC). Deprotection of the aminoterminal Fmoc-group was achieved using 20% piperidine in DMF in the presence of 0.1 M Oxyma. During the synthesis cycles all

amino acids were heated to 90 °C (histidine to 50 °C). Peptides were cleaved from the resin for analytical purposes by a standard cleavage cocktail of 94% TFA, 2% triethylsilane, 2%

anisole, 2% H2O. Methionine containing peptide 2 was cleaved in the presence of dithiotreitol (DTT) to prevent oxidation. After 1 h of cleavage, peptides were precipitated in cold

diethylether, washed with diethylether and dried _in vacuo_ prior to LC-MS analysis. RP-HPLC Peptides were analyzed by chromatography using an analytical RP-HPLC from Agilent Technolgies

(920-LC or 1260 Infinity) using either a Phenomenex Hypersil 5 u BDS C18 LC column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, 130 Å) or a Phenomenex Luna 5 u C18 (2) column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, 100 Å). Peptides

were isolated by semi-preparative RP-HPLC (Varian) using a Phenomenex Luna 5 u C18 LC column (250 × 12.2 mm, 5 μm, 100 Å). Eluent A (water) and eluent B (90% aq. MeCN) each contained 0.1%

trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). ESI-MS ANALYSIS OF PEPTIDES ESI mass spectra were measured on a Shimadzu LCMS-2020 equipped with a Phenomenex Synergi 4 u Hydro-RP LC column (250 × 4.6 mm, 4 μm,

80 Å) by using an eluent system consisting of eluent A (0.1% aq. formic acid, LC-MS grade) and eluent B (100% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid, LC-MS grade). MALDI-TOF-MS ANALYSIS OF

INTACT MASSES 20 μg of protein was used for non-reduced and reduced (30 min at 60 °C with 5 mM Dithiothreitol) sample preparation. Prior MALDI analysis on an Ultraflex III (Bruker, Bremen),

samples were desalted and concentrated with C4 ZipTips (Millipore, Cork) corresponding to the manufactures guide. The prepared samples were directly mixed in equal volumes with saturated

alpha-Cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid matrix (Bruker, Bremen) on a MTP AnchorChip 384 TF plate (Bruker, Bremen). The Ultraflex III was used in a linear positive mode and data acquisition was

performed in a mass range between m/z 10000 to 180000. Per sample, 4000 laser shot were accumulated and finally smoothed and baseline subtracted. CAPLC-ESI-MS ANALYSIS OF INTACT MASSES For

intact mass analysis of heavy and light chain, 20 μg of each sample was mixed with 1% mercaptoethanol final concentration and reduced for 30 min. at 37 °C. Reduced samples were loaded

directly onto a CapLC-MS system (1100 series, Agilent Technologies) coupled to a Synapt G1 HDMS (Waters, Milford, MA) operated in MS positive ion mode. 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water was

used as solvent A and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in 70% n-propanol as solvent B. The samples were separated via a Zorbax SB300 C8 column (3.5 μm, 150 × 0.3 mm, Agilent Technologies),

tempered at 75 °C. The gradient started with 3% B and a flow rate of 10 μL/min followed by a linear gradient from 2 to 39 min from 10% B to 60% B. Protein signals were recorded with a

DA-detector at 214 and 280 nm. MS spectra were acquired from m/z 500 to 3000. Finally, intact protein mass was calculated applying the MaxEnt1 deconvolution algorithm. NANOLC-ESI-MSE

ANALYSIS OF TRYPTIC PEPTIDES Investigation of the payload conjugation site was performed by peptide mapping analysis using a slightly modified RapiGest SF Surfactant care and use protocol

(Waters, Milford, MA). Briefly, 10 μg of each sample was mixed with RapiGest 0.1% final concentration and reduced for 30 min at 60 °C with 5 mM Dithiothreitol. Alkylation was performed with

15 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min at RT. Finally 1.5 μL of a 1 μg/μl trypsin solution were added and incubated overnight at 37 °C. After digestion, the sample was acidified by addition of 0.5%

trifluoroacetic acid and analyzed by Nano-LC-MSe using a nanoAcquity UPLC coupled to a Synapt G1 HDMS (Waters, Milford, MA) operated in MSe mode. 0.1% formic acid in water was used as

solvent A and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile as solvent B. Tryptic peptides were injected and trapped for 3 min on a Symmetry C18 pre-column (5 μm, 180 μm × 20 mm, Waters, Milford, MA)

with a flow rate of 10 μl/min. Separation was performed using an UPLC 1.7 μm BEH130 column (C18, 75 μm × 100 mm, Waters) with a flow rate of 450 nl/min, starting with 2% B from 0 to 2 min

followed by a linear gradient from 8–35% B for 67 min. The used MSe mode combines an alternating MS and MSe (full mass range fragmentation) function each second. Spectra were acquired from

m/z 50 to 1600 and extracted ion chromatograms were analyzed manually. SYNTHESIS OF PEPTIDE CONJUGATES 1–4 Resin-bound peptides were functionalized with 5/6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine

(TAMRA, mixed isomers) or biotin at the free amino terminus by double-coupling using a preactivated carboxyl functionality. For activation, 2 eq. of TAMRA or biotin were incubated with 1.95

eq. of 2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) in the presence of 4 eq. of _N_,_N_-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) in DMF for 10 min shaking. Afterwards,

the mixture was added to the resin-bound peptides (preswelled in 1:1 DMF/DCM) and coupling allowed to proceed for 2 h, respectively. Peptides were cleaved from the resin by using a standard

cleavage cocktail of 94% TFA, 2% triethylsilane, 2% anisole, 2% H2O. Methionine containing SpyTag-peptides were cleaved in the presence of dithiotreitol (DTT) to prevent oxidation. After 2

h of cleavage, peptides were precipitated in cold diethylether, washed twice with diethylether, dried _in vacuo_, and afterwards purified by semi-preparative RP-HPLC. SYNTHESIS OF KTAG WITH

_N_-TERMINAL ALKYNE FUNCTIONALITY KTag-peptide was equipped with an _N_-terminal alkyne functionality by coupling with propargylacetic acid (4-pentynoic acid) on resin. For this purpose, 4

eq. of the building block was preactivated for 10 min with 3.95 eq. of 2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and 8 eq. of

_N_,_N_-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) in DMF and afterwards added to the resin-bound peptide (preswelled in 1:1 DMF/DCM). Coupling was performed for 1.5 h twice and the resin washed

subsequently with DMF, DCM, and diethylether for drying. The alkyne-functionalized peptide was cleaved from the resin using a standard cleavage cocktail of 94% TFA, 2% triethylsilane, 2%

anisole, 2% H2O. After 2 h of cleavage, the peptide was precipitated in cold diethylether, washed twice with diethylether and dried _in vacuo_. The product was analyzed by LC-MS and purified

by semi-preparative RP-HPLC. SYNTHESIS OF PEPTIDE-TOXIN CONJUGATE 5 Resin-bound KTag-peptide was incubated with 1.2 eq. MMAE bearing a carboxy group in the presence of 1.14 eq.

2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and 2.4 eq. of _N_,_N_-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) in DMF for 5 h at room temperature. Afterwards, the resin

was washed twice with DMF, DCM, and diethylether. The toxin-functionalized peptide was cleaved from the resin using a cleavage cocktail of 85% TFA, 5% triethylsilane, 5% anisole, and 5% H2O

for 1 h at room temperature. The peptide-toxin conjugate was precipitated in cold diethylether, washed twice with diethylether and dried _in vacuo_. Compound 5 was isolated by RP-HPLC.

SYNTHESIS OF PEPTIDE-TOXIN CONJUGATES 6 AND 7 KTag was coupled to monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) via Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC). For this purpose, the peptide bearing

an amino terminal alkyne functionality (1 mg/ml) was reacted with 1.5 eq. MMAE holding an azide functionality in the presence of 4 eq. of Cu(II)-TBTA complex, 4 eq. of

_N_,_N_-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), and 4 eq. of sodium ascorbate for 5 h at room temperature in water. The water was degassed by flushing it with argon prior to usage. TBTA was dissolved

at a concentration of 10 mM in 1:4 DMSO/tBuOH and the complex formed by addition of Cu(II)SO4 5xH2O. The toxin was pre-dissolved in 50% MeCN. The reaction was monitored by HPLC-MS.

Peptide-toxin conjugates 6 and 7 were isolated by semi-preparative RP-HPLC. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Siegmund, V. _et al_. Spontaneous Isopeptide Bond Formation as a

Powerful Tool for Engineering Site-Specific Antibody-Drug Conjugates. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 39291; doi: 10.1038/srep39291 (2016). PUBLISHER'S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard

to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. REFERENCES * Chu, Y.-W. & Polson, A. Antibody-drug conjugates for the treatment of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s

lymphoma and leukemia. Future Oncol. 9, 355–68 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ricart, A. D. Antibody-drug conjugates of calicheamicin derivative: Gemtuzumab ozogamicin and

inotuzumab ozogamicin. Clinical Cancer Research 17, 6417–6427 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hamblett, K. J. et al. Effects of drug loading on the antitumor activity of a

monoclonal antibody drug conjugate. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 7063–7070 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * McDonagh, C. F. et al. Engineered antibody-drug conjugates with defined

sites and stoichiometries of drug attachment. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 19, 299–307 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sochaj, A. M., Swiderska, K. W. & Otlewski, J. Current

methods for the synthesis of homogeneous antibody-drug conjugates. Biotechnol Adv., doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.05.001 (2015). * Schumacher, D., Hackenberger, C. P. R., Leonhardt, H.

& Helma, J. Current Status: Site-Specific Antibody Drug Conjugates. J. Clin. Immunol. 1–8, doi: 10.1007/s10875-016-0265-6 (2016). * Junutula, J. R. et al. Site-specific conjugation of a

cytotoxic drug to an antibody improves the therapeutic index. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 925–32 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hofer, T., Skeffington, L. R., Chapman, C. M. &

Rader, C. Molecularly defined antibody conjugation through a selenocysteine interface. Biochemistry 48, 12047–12057 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Li, X., Yang, J. &

Rader, C. Antibody conjugation via one and two C-terminal selenocysteines. Methods 65, 133–138 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhang, C. et al. π-Clamp-mediated cysteine

conjugation. Nat. Chem. 8, 1–9 (2015). Google Scholar * Jones, M. W. et al. Polymeric dibromomaleimides as extremely efficient disulfide bridging bioconjugation and pegylation agents. J.

Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 1847–1852 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Badescu, G. et al. Bridging disulfides for stable and defined antibody drug conjugates. Bioconjug. Chem. 25,

1124–1136 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Maruani, A. et al. A plug-and-play approach to antibody-based therapeutics via a chemoselective dual click strategy. Nat. Commun. 6,

6645 (2015). Article CAS ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhou, Q. et al. Site-specific antibody-drug conjugation through glycoengineering. Bioconjug. Chem. 25, 510–520 (2014). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Drake, P. M. et al. Aldehyde tag coupled with HIPS chemistry enables the production of ADCs conjugated site-specifically to different antibody regions with

distinct _in vivo_ efficacy and PK outcomes. Bioconjug. Chem. 25, 1331–1341 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Grünewald, J. et al. Efficient Preparation of

Site-Specific Antibody-Drug Conjugates Using Phosphopantetheinyl Transferases. Bioconjug. Chem. 26, 2554–2562 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Beerli, R. R., Hell, T., Merkel, A.

S. & Grawunder, U. Sortase Enzyme-Mediated Generation of Site-Specifically Conjugated Antibody Drug Conjugates with High _In Vitro_ and _In Vivo_ Potency. PLoS One 10, e0131177 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Dennler, P. et al. Transglutaminase-Based Chemo-Enzymatic Conjugation Approach Yields Homogeneous Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Bioconjug.

Chem. 25, 569–578 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Strop, P. et al. Location matters: Site of conjugation modulates stability and pharmacokinetics of antibody drug conjugates.

Chem. Biol. 20, 161–167 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Siegmund, V. et al. Locked by Design: A Conformationally Constrained Transglutaminase Tag Enables Efficient

Site-Specific Conjugation. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 54, 13420–13424 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kang, H. J., Coulibaly, F., Clow, F., Proft, T. & Baker, E. N. Stabilizing

isopeptide bonds revealed in gram-positive bacterial pilus structure. Science 318, 1625–8 (2007). Article CAS ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Zakeri, B. et al. Peptide tag forming a rapid

covalent bond to a protein, through engineering a bacterial adhesin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E690–7 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zakeri, B. &

Howarth, M. Spontaneous intermolecular amide bond formation between side chains for irreversible peptide targeting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 4526–4527 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Fierer, J. O., Veggiani, G. & Howarth, M. SpyLigase peptide-peptide ligation polymerizes affibodies to enhance magnetic cancer cell capture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111,

E1176–81 (2014). Article CAS ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Veggiani, G., Zakeri, B. & Howarth, M. Superglue from bacteria: Unbreakable bridges for protein

nanotechnology. Trends in Biotechnology 32, 506–512 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Dubowchik, G. M. et al. Cathepsin B-labile dipeptide linkers for lysosomal

release of doxorubicin from internalizing immunoconjugates: Model studies of enzymatic drug release and antigen-specific _in vitro_ anticancer activity. Bioconjug. Chem. 13, 855–869 (2002).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Doronina, S. O. et al. Novel peptide linkers for highly potent antibody-auristatin conjugate. Bioconjug. Chem. 19, 1960–1963 (2008). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Rusnak, D. W. et al. Assessment of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR, ErbB1) and HER2 (ErbB2) protein expression levels and response to lapatinib (Tykerb®,

GW572016) in an expanded panel of human normal and tumour cell lines. Cell Prolif. 40, 580–594 (2007). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kornberger, P. & Skerra, A.

Sortase-catalyzed _in vitro_ functionalization of a HER2-specific recombinant Fab for tumor targeting of the plant cytotoxin gelonin. MAbs 6, 354–366 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar

* Swee, L. K. et al. Sortase-mediated modification of αDEC205 affords optimization of antigen presentation and immunization against a set of viral epitopes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110,

1428–33 (2013). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Paterson, B. M. et al. Enzyme-mediated site-specific bioconjugation of metal complexes to proteins: Sortase-mediated

coupling of copper-64 to a single-chain antibody. Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 53, 6115–6119 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project has been

funded by Merck KGaA Darmstadt in context of the Merck Biopharma Innovation Cup. The authors thank the members of the team Chemo- and Bioengineering Pedro Matos, Sara Cleto, Darryl

Gibbings-Isaac, Reswita Dery G from the Innovation Cup 2013 and Siegfried Neumann for giving inspiration for this project. It was also inspired by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SPP1623.

The authors thank Dirk Müller-Pompalla (Merck KGaA) for SEC-analysis of peptide-tagged antibodies. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Institute of Organic Chemistry and

Biochemistry, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, 64287, Germany Vanessa Siegmund & Harald Kolmar * Merck KGaA, Frankfurter Straße 250, Darmstadt, 64293, Germany Vanessa

Siegmund, Birgit Piater, Thomas Eichhorn, Frank Fischer, Carl Deutsch, Stefan Becker, Lars Toleikis, Björn Hock & Ulrich A. K. Betz * EMD Serono Research & Development Institute,

Inc., 45A Middlesex Turnpike, Billerica, 01821, MA, USA Bijan Zakeri Authors * Vanessa Siegmund View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Birgit

Piater View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Bijan Zakeri View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Thomas Eichhorn View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Frank Fischer View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Carl Deutsch View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Stefan Becker View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lars Toleikis View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Björn Hock View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ulrich A. K. Betz View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Harald Kolmar View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS V.S., B.P., F.F., and H.K. conceived and designed the experiments, V.S. and T.E. conducted the

experiments, C.D. designed and supplied the cytotoxic compounds used for peptide coupling, V.S., B.P., T.E., F.F., S.B., L.T., B.H., U.A.K.B., and H.K. analyzed the results, V.S., B.P.,

B.Z., and H.K. wrote the manuscript, and all authors reviewed the manuscript. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS B.Z. receives royalties from Oxford University on spontaneous isopeptide

bond formation technology and declares competing financial interest. ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated

otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To

view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Siegmund, V., Piater, B., Zakeri, B. _et al._

Spontaneous Isopeptide Bond Formation as a Powerful Tool for Engineering Site-Specific Antibody-Drug Conjugates. _Sci Rep_ 6, 39291 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39291 Download

citation * Received: 19 August 2016 * Accepted: 21 November 2016 * Published: 16 December 2016 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39291 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link

with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(319x0:321x2)/people_social_image-60e0c8af9eb14624a5b55f2c29dbe25b.png)