- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT When defending against hostile enemies, individual group members can benefit from others staying in the group and fighting. However, individuals themselves may be better off by

leaving the group and avoiding the personal risks associated with fighting. While fleeing is indeed commonly observed, when and why defenders fight or flee remains poorly understood and is

addressed here with three incentivized and preregistered experiments (total _n_ = 602). In stylized attacker-defender contest games in which defenders could stay and fight or leave, we show

that the less costly leaving is, the more likely individuals are to abandon their group. In addition, more risk-averse individuals are more likely to leave. Conversely, individuals more

likely stay and fight when they have pro-social preferences and when fellow group members cannot leave. However, those who stay not always contribute fully to group defense, to some degree

free-riding on the efforts of other group members. Nonetheless, staying increased intergroup conflict and its associated costs. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS GENEROUS WITH

INDIVIDUALS AND SELFISH TO THE MASSES Article 29 July 2021 CORRUPT THIRD PARTIES UNDERMINE TRUST AND PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOUR BETWEEN PEOPLE Article 27 October 2022 THE RELATIONSHIP OF THE SOURCE

OF PUNISHMENT AND PERSONALITY TRAITS WITH INVESTMENT AND PUNISHMENT IN A PUBLIC GOODS GAME Article Open access 09 September 2024 INTRODUCTION Among humanities’ most pressing problems are

the intergroup conflicts that destroy social welfare, cripple economies, and create persistent and large-scale refugee flows around the globe1. When drawn into conflict, individuals directly

or indirectly contribute to raids against other groups or to protect against such enemy hostilities2,3. In the latter case, when defending against hostile outgroups, groups need to ensure

that (enough of) their members contribute to conflict. This is non-trivial, as fighting entails myriad risks to individual participants, including economic losses, physical injury and, in

extremis, death. Accordingly, rather than actively contributing to collective defense against out-group hostilities, individuals may abandon their group and flee from conflict. Such

decisions to leave rather than stay are indeed commonly observed. During intergroup conflict, armies experience desertion and refugees abandon their homes4,5, possibly leaving behind fellow

group members. As a case in point, archival data have shown that conflicts increase migration, especially in low-income countries1. At the same time, there are also numerous examples of

individuals who could have left easily and at low cost yet decided to stay and fight for their group. When and why individuals decide to stay or flee from conflict situations is poorly

understood, and the psychological and economic mechanisms underlying such decisions remain unknown. Filling this gap is important, as stay-or-leave decisions can have important effects on

how intergroup conflict develops and shapes individual and group outcomes. Individuals who leave may be considered less brave and heroic, yet these individuals increase their probability to

survive compared to those who stay. However, whether those who stay indeed are more likely to incur costs to protect themselves and their group remains an open question. Moreover, and all

else equal, the more people leave upon impending outgroup attacks, the less is needed to settle the conflict—leaving conflict, rather than staying and fighting, can reduce the intensity of

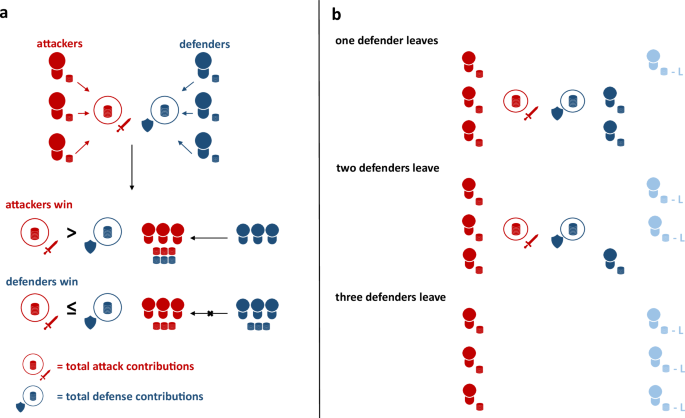

intergroup conflict and preserve collective welfare. Here we address the micro foundations of stay-or-leave decisions during conflict using a newly developed Intergroup Attacker-Defender

Contest with an Exit option (IADC-E; Fig. 1) allowing to test predictions on voluntary conflict participation in a controlled and stylized experimental setting. The contest models

individuals nested in two groups, one being designated attacker and the other defender3,6,7. Attackers can individually contribute to conflict, as can defenders. Contributions to conflict

are non-recoverable and can never be earned back. However, when attackers’ contributions combined exceed those of the defender group, the attackers win the conflict and earn the defenders’

non-invested Experimental Money Units (henceforth EMU); otherwise, both sides keep what they did not invest in conflict. Importantly, defenders have two options: (i) stay and defend

themselves and their group (as in previous studies on attacker-defender contests), or (ii) leave their group to evade the attack from the opposing group. Having these two options creates a

social dilemma for defenders: should they prioritize personal earnings and survival by leaving their group behind, or should they stay and fight, also for the sake of fellow group members?

Because our task clearly specifies the different actions and underlying incentives of conflicting parties in a controlled environment8,9,10, we can observe whether, when, and why individuals

stay and help with collective defense or, alternatively, leave and abandon their group. We anticipated, first, that defenders’ willingness to abandon their group depends on the personal

(economic) cost of leaving and we hypothesized that defenders leave when its personal benefits outweigh the expected benefits of conflict participation11,12. Relatedly, we expected that, if

the cost of leaving is not at a maximum, individuals who are more risk averse may be more inclined to leave, given that staying in a conflict involves a risk of defeat—an outcome to which

risk-averse individuals are particularly sensitive12,13,14. Loss aversion could also increase defenders’ willingness to leave: the possibility that defenders could lose everything if they

stay may loom larger than any potential gains15,16. An individual-level cost-benefit analysis of staying or leaving can be considered selfish, since it only considers own outcomes and can

result in other group members being left behind. Consequently, group members who are left behind need to (and are expected to17) fight harder to not be defeated and, as a result, have to

waste more resources on conflict. In the decision to leave, people may therefore not only be motivated by self-centered cost-benefit considerations but also (to different degrees) by social

considerations of solidarity—the psychological bond felt with and commitment to fellow in-group members18—and the concern for others’ welfare (henceforth pro-sociality)19. Archival data

indeed revealed that the likelihood of deserting groups (negatively) correlates with the presence of group norms of cooperation and solidarity5, and past experiments have shown that

pro-social preferences influence how much people contribute to group defense3,20,21,22,23. Interestingly, there is some evidence suggesting that individuals with pro-social preferences may

invest in collective defense especially to protect vulnerable others who lack the financial means, social capital, or physical ability to defend themselves24. Possibly, individuals who can

leave, even at low cost, may therefore be less likely to leave when others in their group cannot. Here, we show across three studies in which participants were confronted with the IADC-E

(Fig. 1), that higher economic costs of leaving reduce the likelihood that defenders abandon their group, in line with a self-centered cost-benefit account. Yet even when the cost of leaving

is low, people are likely to stay and defend especially when they have pro-social preferences and some fellow group members cannot leave. This has adverse consequences, however. When more

defenders stay, both attacker and defender groups increase their contributions to conflict, wasting more EMU and lowering collective welfare on both sides. Outside of conflict situations,

pro-social concerns for others play an important role to uphold cooperation and social relations in groups25,26,27. Our findings show that in intergroup conflicts, these pro-social concerns

not only decrease conflict exit but also increase the overall economic waste and cost associated with intergroup conflicts, at least in the short run. RESULTS All studies embedded

participants in the IADC-E (Fig. 1): Six participants were randomly divided in three-person attacker and defender groups and made decisions across a series of contest rounds. On each round,

defenders were simultaneously given the option to leave at some cost (which varied across rounds and individuals). If defenders left, they evaded the attack by the other group. If they did

not leave, they decided how much of their EMU to contribute to conflict. On each round, attackers and defenders were first informed how many defenders decided to leave, and then decided

whether and how much to invest in conflict. Whereas EMU contributed to conflict were always wasted and could never be earned back, attackers appropriated the non-contributed EMU of the

defenders who did not leave when the collective investment in attack exceeded the collective investment in defense (in that case, defenders who stayed earned nothing). When defenders who

stayed contributed equal or more to conflict than attackers, they successfully defended themselves, and both the attackers and defenders (who stayed) earned their non-contributed EMU.

Defenders who left earned their original endowment minus the cost of leaving, regardless of the outcome of the conflict between their attackers and the (remaining) defenders in their group.

We designed study 1 to specify at what (financial) costs defenders were willing to leave their group. Participants (_n_ = 122), in the role of defenders, were given 20 EMU to use in the

IADC-E and indicated if they wanted to leave for cost levels varying between 0 and 20 EMU. As predicted, defenders were less likely to leave when leaving became increasingly costly (Fig.

2a). When leaving did not cost anything, the majority (92%) of participants left. However, when leaving costed more than half of their endowment, more than 90% of participants decided to

stay. This shows that (i) defenders are sensitive to leaving costs in line with a simple individual-level cost-benefit account. At the same time, when we compare decisions to game-theoretic

benchmarks and prior data, (ii) defenders seem to overestimate the value they can gain from staying in the conflict. That is, when we fit a simple model using maximum likelihood to

defenders’ stay-or-leave decisions, we see that defenders’ decisions in study 1 were consistent with expected earnings of 12.7 EMU from staying in the conflict. However, the mixed strategies

Nash Equilibrium in the Intergroup Attacker-Defender Contest without exit options (IADC-NE) implies expected earnings of 11.4 EMU for those who stay in conflict6,28. In addition, past

studies revealed a weighted average earning of only 6.13 EMU (see Methods section for more information)6,29,30. Thus, in our one-shot IADC-E, defenders chose to stay for costs at which,

based on game-theoretic benchmarks and prior data, leaving would have been the economically superior choice. Next, we conducted an interactive behavioral study in fixed groups faced with the

IADC-E to test the impact of conflict dynamics, such as conflict history. In study 2 (_n_ = 240 participants), groups of attackers and defenders interacted in four blocks of ten rounds

each. Between blocks, we manipulated the cost of leaving, with costs varying between 5, 7, and 10 EMU (out of their endowment of 20). We also introduced one block in which leaving was not

possible. Decisions were incentivized such that participants were paid out based on the average of eight randomly selected rounds (i.e., two decisions per block; see Methods section for more

information). In line with study 1, defenders were less likely to leave when leaving became increasingly costly (multilevel logistic model [MLLM], _z_ = 3.18, _b_leaving cost 5 vs leaving

cost 7 = 0.50, _p_ = 0.001, 95% CI [0.22, 0.82], see online Supplementary Information Table S1; MLLM, _z_ = −4.03, _b_leaving cost 7 vs leaving cost 10 = −0.58, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI

[−0.87, −0.30], see Table S1). This was also in line with participants’ beliefs: they expected that fewer defenders would leave under higher leaving costs (multilevel model [MLM], _t_(6958)

= 9.57, _b_leaving cost 5 vs leaving cost 7 = 0.20, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [0.16, 0.24], see Table S2; MLM, _t_(6958) = −25.51, _b_leaving cost 7 vs leaving cost 10 = −0.53, _p_ < 0.001,

95% CI [−0.57, −0.49], see Table S2). Defenders were also more likely to leave if they were more risk averse (as measured with a separate task31; MLLM, _z_ = −2.70, _b_risk taking = −0.05,

_p_ = 0.007, 95% CI [−0.09, −0.02], see Table S1). Importantly, success dynamics across rounds played an important role for leaving decisions. Defenders were more likely to leave if they

were defeated on the previous round (MLLM, _z_ = −8.72, _b_previous success = −1.13, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [−1.41, −0.88], see Table S1). These findings corroborate that defenders are

sensitive to individual costs and benefits when deciding to leave or stay, and integrate past success or failure experiences in such decision-making. Leaving decisions also influenced the

intensity of conflict and group-level outcomes. Group-level contributions to conflict increased when fewer defenders left (both for attacker and defender groups; MLM attackers, _t_(1104.76)

= 7.69, _b_num defenders = 3.13, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [2.33, 3.92], see Table S3; MLM defenders, _t_(1110.36) = 12.20, _b_num defenders = 4.34, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [3.64, 5.03], see

Table S4). On the group level, leaving was economically the best choice: Fewer EMU were wasted on conflict when more defenders decided to leave (see also Fig. 2b). However, defender groups

contributed more to conflict (MLM, _t_(1113.09) = −7.58, _b_leave possible = −4.69, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [−5.91, −3.48], see Table S4) and were most successful in their defense against the

attackers when they could not leave (MLLM, _z_ = −3.57, _b_leave possible = −0.71, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [−1.10, −0.32], see Table S6; see also Fig. 2b). Hence, forcing defenders to stay

led to the highest economic waste of conflict (i.e., 38% of EMU were wasted on conflict) yet also made enemy attacks least successful (i.e., defenders successfully defended themselves in 77%

of rounds when leaving was not possible). This illustrates the social dilemma that the option to leave created: while fewer EMU were wasted on conflict when defenders could leave, it came

at the expense of a lower defense success rate. On the individual level, leaving was likewise the economically superior decision for defenders (Fig. 2c). Across all cost levels, and

regardless of the number of defenders who stayed, participants who left earned the most (MLM, _t_(3416.64) = −33.67, _b_stay = −6.03, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [−6.38, −5.67], see Table S7). As

a result, the ability to leave created, besides a social dilemma, a coordination problem for defenders: defenders should either all leave, or should all stay, as any mixture of some staying

and some leaving resulted in lower individual earnings overall (MLM, _t_(3310.09) = 14.12, _b_dummy coordination = 2.60, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [2.24, 2.96], see Table S8). Whereas

defenders earned more when they left, and avoiding conflict increased individual and collective welfare even when leaving was very costly, a non-trivial proportion of defenders who could

exit nevertheless decided to stay and confront their attackers. These defenders’ decisions were clearly not only driven by personal cost-benefit considerations. Indeed, and even when leaving

was cheap, defenders in study 2 were less likely to leave if their fellow group members stayed on the previous round (MLLM, _z_ = −8.72, _b_previous others stayed = −1.08, _p_ < 0.001,

95% CI [−1.33, −0.84], see Table S1), showing that over and beyond previous group success or failure, defenders were also influenced by others’ decisions. Furthermore, defenders were less

likely to leave when they had a higher social value orientation angle (indicating stronger pro-social preferences, as measured with a separate task19; MLLM, _z_ = −3.14, _b_svo angle =

−0.03, _p_ = 0.002, 95% CI [−0.04, −0.01], see Table S1). Finally, defenders who stayed reported higher ingroup solidarity after the contest (MLM, _t_(3505) = 12.76, _b_stay = 0.36, _p_ <

0.001, 95% CI [0.30, 0.41], see Table S9; replicated in study 3, MLM, _t_(2307) = 10.91, _b_stay = 0.41, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [0.34, 0.49], see Table S20). In short, these results suggest

that economic incentives to leave are counteracted by pro-social considerations, including solidarity with and imitation of fellow group members who stayed and general pro-social

preferences. To more directly investigate the influence of pro-social considerations in the decision to leave or stay, we introduced asymmetric leaving opportunities (_n_ = 240

participants). In study 3, the cost of leaving was fixed to 5 EMU (i.e., 25% of the individual’s endowment), a cost level at which most participants, under equal leaving opportunities,

decided to leave the conflict in study 1 (74.59%) and in study 2 (77.67%). In study 3, however, leaving was not always possible for all group members. Specifically, we compared four

conditions in which (i) no defenders could leave, (ii) one defender could leave, (iii) two defenders could leave, or (iv) all three defenders could leave (decisions were again incentivized

based on the average of eight randomly selected rounds; see Methods section for more information). Thus, for those conditions in which only one or two defenders could leave, the decision to

leave also meant leaving others behind. In these asymmetric scenarios, defenders who were able to leave were significantly less likely to do so compared to when all defenders could leave

(Fig. 3a; MLLM, _z_ = −16.07, _b_asymmetric leave = −1.94, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [−2.19, −1.71], see Table S10). That is, when all defenders could leave, defenders left in 71.58% of the

cases. When one or two defenders could not leave, however, leaving decreased to 38.75% and 39.00%, respectively. Furthermore, defenders who could leave under asymmetric leaving opportunities

earned less EMU compared to when everyone could leave (MLM, _t_(3556.78) = −6.89, _b_dummy could leave = −1.47, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [−1.90, −1.04], see Table S17). These defenders thus

stayed and contributed to conflict at the expense of their own earnings when one or two fellow group members could not leave. Decisions to stay also contributed to group survival, as

defender groups were more successful in their defense against the attackers when groups consisted of more defenders under asymmetric leaving abilities (MLLM, _z_ = 4.58, _b_num defenders =

0.52, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [0.30, 0.75], see Table S15). The increased likelihood to survive enemy attack under asymmetric leaving emerged mainly because those defenders who could not

leave fought harder. On average, defenders under asymmetric leaving abilities who could not leave contributed more than when leaving was not possible for anyone (MLM, _t_(2358.98) = 6.59,

_b_dummy could leave = 1.07, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [0.75, 1.39], see Table S12) and compared to those who could leave but decided to stay (MLM, _t_(1341.53) = −5.72, _b_stayed | could leave

= −1.44, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [−1.93, −0.94], see Table S13; Fig. 3b). As a result, defenders forced to stay in the conflict earned significantly less compared to the situation in which

no defenders could leave and groups had to fight together (MLM, _t_(39) = −12.49, _b_dummy could leave = −5.45, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [−6.31, −4.58], see Table S16). Thus, when some

defenders can leave, those who cannot leave invest more and earn less. Although defenders who could leave but stayed under asymmetric leaving opportunities did not contribute fully to group

defense, they seemed to stay predominantly out of social concerns. First, 51.43% of all defenders who stayed under asymmetric leaving opportunities invested more EMU than the cost of leaving

(Fig. 3b). Hence, they clearly sacrificed EMU and earned less than when they would have left, regardless of the outcome of the conflict. Furthermore, 12.82% of the defenders who stayed

under asymmetric leaving opportunities invested exactly 25% of their endowment (i.e., the cost of leaving), thereby staying but cooperating under the risk of possible defeat. Second, and as

a result, defenders who stayed under asymmetric leaving opportunities earned less than those who left, on average (i.e., thereby making a net loss when staying; MLM, _t_(1133.69) = −17.18,

_b_stay = −5.99, _p_ < 0.001, 95% CI [−6.67, −5.30], see Table S19). Third, defenders with pro-social preferences (i.e., a higher social value orientation angle, measured with a separate

task19) were more likely to stay and help their fellow group members (MLLM, _z_ = −3.16, _b_svo angle = −0.06, _p_ = 0.002, 95% CI [−0.09, −0.03], see Table S11). Moreover, pro-social

defenders contributed more to conflict under asymmetric leaving opportunities (MLM, _t_(101.34) = 2.76, _b_svo angle = 0.06, _p_ = 0.007, 95% CI [0.02, 0.11], see Table S13), whereas there

was no statistically significant effect of social preferences on conflict contributions when all defenders could leave (MLM, _t_(51.78) = 1.45, _b_svo angle = 0.06, _p_ = 0.153, 95% CI

[−0.02, 0.13], see Table S14). We also found no statistically credible evidence that social preferences impacted conflict contributions in study 2 when all defenders could leave (i.e., under

different costs; MLM, _t_(86.20) = 1.48, _b_svo angle = 0.03, _p_ = 0.143, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.08], see Table S5). Together, this shows that defenders (stayed and) contributed to conflict

under asymmetric leaving opportunities primarily due to the presence of fellow group members who could not leave, and that these choices are moderated by individual social preferences.

However, the fact that defenders who could not leave invested more EMU to conflict can create opportunities for those who could leave to stay and free-ride on the increased fighting efforts

by those who cannot leave. Defenders who could leave but stayed may therefore not always do so because of pro-social concerns for their group, but sometimes because of selfish attempts to

exploit their fellows’ inability to leave and being forced to fight (see also Fig. 3b). This is indeed what we found, at least for some individuals: 35.74% of defenders who stayed

voluntarily contributed less to conflict than the leaving cost, suggesting that they tried to earn more than their outside option of leaving. And, indeed, in 69.85% of the cases in which

defenders who stayed voluntarily but invested less than the leaving cost, they managed to earn more than the cost of leaving (i.e., successfully free-rode). Overall, pro-social defenders

earned less than defenders with selfish preferences (MLLM, _t_(118) = −2.67, _b_svo angle = −0.06, _p_ = 0.009, 95% CI [−0.11, −0.02], see Table S18; also see Fig. 3c). Compared to selfish

defenders, pro-social defenders committed more to collective defense, prioritizing group interests over personal gain. DISCUSSION Extant work has investigated when and how people decide to

participate in and contribute to conflict32,33. Here we considered a complementary perspective. Across three studies we used stylized experiments modeling the asymmetric structure of

intergroup conflicts to investigate the causal dynamics of leaving conflicts. We found that individual-level cost factors increased the likelihood that defenders abandoned their group.

Defenders were more inclined to leave when it was less costly for them to do so, when they were risk averse, and after they experienced defeat, resonating with the idea that they were

primarily concerned with maximizing personal gains (also see refs. 34,35,36; also resonating with findings on the emergence of coalitionary violence13,14). Asymmetric leaving opportunities

increased voluntary conflict participation at a personal cost and increased waste on conflict, showing that people may stay to help others who cannot leave. Follow-up analyses suggest that

staying, however, can be driven by mixed motivations under asymmetric leaving abilities. Some participants (35.74%) stayed due to strategic concerns. These individuals attempted to

free-ride, benefiting from the conflict contributions of those who did not have the ability to leave (also see refs. 37, 38). Most participants (64.26%), however, stayed at a personal cost,

thereby helping to successfully defend fellow group members that could not leave (also see refs. 3, 23). Concerns for others are crucial for groups to uphold cooperation and building and

maintaining public goods25,26,27. While cooperation is often celebrated for its role in fostering collective well-being, it is important to recognize that mechanisms enabling

cooperation—such as concerns for others—can also provide impetus for escalating intergroup conflicts. Because people care about others, they may be more likely to stay, fight, and

(inadvertently) contribute to conflict spirals. In a similar vein, it has been argued that social concerns can foster corruption39,40, likewise highlighting how cooperative behaviors can

sometimes lead to increased, possibly unintended, social costs. People may perceive the choice to defend rather than leave also as a social norm or moral obligation. If strong enough, this

could help groups to coordinate on collectively taking part in the conflict. In the long-run, well-coordinated, voluntary conflict participation could actually reduce the likelihood of

conflicts, as attackers may shy away from attacking groups with a reputation of strong solidarity. Future work could investigate whether credible signals of commitment can lead to a

de-escalation of conflict and to which degree such commitment can be explained by moral preferences and specific moral dimensions, such as heroism and helping one’s group41,42. Our model of

intergroup conflict captures some of the basic principles of coalitionary conflict and intergroup warfare8,9,10. Examples include mass migrations from Syria following the outbreak of the

civil war in 2011 and, more recently, following the invasion of Russian forces into Ukrainian territory. Our study suggests that economic factors tend to motivate people to abandon their

group. Conversely, social concerns such as solidarity and concerns for fellow group members reduce leaving, thereby increasing the ability of groups to successfully defend themselves. And

yet, while our stylized game-theoretic context allows to manipulate exit costs and leaving opportunities to reveal their causal impact on conflict participation and escalation relative to

baseline treatments, generalizing findings to migration and desertion during these and other real-world conflicts requires caution. Outside experimental laboratories, in-group members share

certain features with each other that may increase their feelings of group identity43. In our study, groups were formed randomly between anonymous participants, likely leading to

comparatively low levels of ingroup identification. While this may result in an underestimation of defenders’ willingness to stay, even in our minimal setting, a significant proportion of

participants chose to stay, especially those who were prosocial and who experienced more ingroup solidarity. In real-life situations, where group solidarity and care for fellow members are

presumably stronger, defenders may be even more committed to stay and fight, potentially escalating intergroup conflict beyond what our studies indicate. Our experiments did not provide

attackers with the option to leave (or not enter) a conflict, because attackers in the standard intergroup contests already can opt out by simply not investing any EMU (which we observe in

36.78% of the cases in study 2, and in 40.08% of the cases in study 3). Nevertheless, giving attackers the option to actively abstain, which would also mean forgoing any benefits from

victory, would allow individual attackers to send a strong (costly) signal of, for example, condemning attacks. The (in)ability to leave on the attacker-side could, thus, allow attackers to

tacitly coordinate on developing social norms of fighting or abstaining and could provide valuable insights into attackers’ motivation and fighting capabilities, rendering this an

interesting avenue for future studies. Attackers and defenders in our experiments were fully aware of the number of defenders who had left and leaving decisions were made simultaneously.

This might not always be the case—in many conflicts misinformation and a lack of transparency are common and of strategic value. For example, attackers and defenders may want to conceal the

true number of deserters to maintain an appearance of strength and to deter their opponents44,45 and people may closely observe what others do and conditionally decide whether to leave or

stay. Future work could investigate the effect of ambiguity of how many defenders left on attackers’ investment and the role of sequential play (given our data only includes conditional

choices across rounds, regarding the latter case). One limitation to our experimental set-up is that leaving came at a financial cost to participants. While applying a financial cost to

leaving allowed us to infer how people integrate costs and benefits in their decision-making, in many conflicts the costs of leaving can be much more substantial and multifaceted, including

non-economic costs like leaving loved ones behind, social capital costs like losing one’s social network, or reputational costs like losing trust of fellow group members46,47. Future

research could expand on the Intergroup Attacker-Defender Contest with Exit to investigate how such factors influence leaving dynamics. Questions for future research and limitations aside,

our findings shed light on the persistence of intergroup conflict and why, in particular, people stay-or-leave when facing hostile outgroups. When exiting is possible, solidarity and

pro-social concerns make some individuals stay and fight, and considerations of personal payoffs make others leave. At the same time, some individuals seemingly stayed because of selfish

reasons—they contributed less to conflict than those who could not leave and thereby increased their own earnings. This is a non-trivial finding, as it means someone’s decision to stay

cannot be taken as unequivocal evidence for their solidarity and pro-social concerns for fellow group members. While humans are characterized as a remarkable cooperative species, intergroup

conflicts, that likewise require cooperation and coordination, is a pervasive and unfortunate constant in human history. Groups frequently attempt to dominate and take advantage of other

groups, that are forced to defend themselves against such hostilities. Defenders, under the threat of attack, encounter a social dilemma: the decision to either prioritize personal gain and

survival by leaving their group behind, or to stay and fight, also for the sake of fellow group members. Outside of conflict situations, social concerns are important for sustaining

cooperation and create mutual benefits. Somewhat paradoxically, as we showed here, social concerns can, however, also exacerbate the intensity and cost tied to intergroup conflicts, at least

in the short run. METHODS STUDY 1 PARTICIPANTS AND ETHICS Study 1 was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology at Leiden University (2021-09-04-C.K.W. de

Dreu-V3-3374) and did not involve deception. The study was programmed in Qualtrics. Participants were recruited via Prolific (_n_ = 132, 48% were female; sample size was determined based on

previous research, no statistical method was used to predetermine sample size). We excluded 10 participants who displayed signs of unserious participation or incorrect task understanding

(see Design section for details). Our final sample thus consisted of 122 participants. These participants were between 18 and 61 years of age (M = 24.66, SD = 6.50), provided informed

consent, and received full debriefing after participating. They received a standard fee of £3.00 and their decisions were fully incentivized (see Incentives section for details).

Participation took ~30 min. DESIGN Participants entered their Prolific ID, read the information letter, and signed the online informed consent. Participants then read instructions for the

Intergroup Attacker-Defender Contest with Exit (Fig. 1). The experimental instructions used neutral language throughout (e.g., terms like in-group defense and out-group attack were avoided).

Participants were instructed that after the experiment they would be randomly assigned to three-person attacker and defender groups, and their decisions (i.e., with regards to leaving if

they were a defender, and conflict contributions for both roles) were implemented and incentivized (see Incentives section for details). After the rules of the task were explained,

participants answered 10 practice questions to probe their understanding of the task. Only after all practice questions were answered correctly, participants could continue with the task.

When passing the instructions, participants were first assigned to the role of defender and asked to predict the total number of EMU that attackers would contribute to attack. Thereafter,

participants’ willingness to pay (WTP) for leaving was assessed using an open-ended question, to determine the upper-bound cost at which they were willing to leave. Following this,

participants indicated for each possible cost of leaving (0, 1, 2, … 20) whether they would leave their (defender) group, and how much they would contribute to defense (0 ≤ g ≤ 20) when they

would stay and 0, 1, or 2 other defenders would leave. Once these measures were taken, participants were assigned to the attacker role and were reminded of what this role entailed. They

indicated their contribution g (0 ≤ g ≤ 20) to attack for each possible number of defenders who stayed (0, 1, 2, or 3). Finally, participants filled in their demographics (age, gender,

education, and country) and were debriefed. To determine serious participation, we included three attention checks. First, after the practice questions, participants were asked to select the

option correct in response to the multiple-choice question: please select correct with the options correct and incorrect. Second, after participants indicated their contribution to the

defender conflict pool, there was an attention check during which participants were asked to enter the (obviously incorrect because impossible) number 150 in response to the question how

many EMU they wanted to contribute to a conflict pool. Finally, before the demographics questionnaire started, participants were asked to type the word green in a response box. The first and

third attention checks were answered correctly by all participants. Only the second attention check was missed by one participant. No participants were excluded from the final analyses

based on the attention checks. We did exclude two participants who, when indicating for each possible cost of leaving whether they would stay-or-leave, had more than two switching points

(e.g., they left when the cost of leaving was 5 EMU, they stayed when the cost of leaving was 6 EMU, they left when the cost of leaving was 7 EMU, etc.), three participants who filled in

their stay-or-leave decisions the other way around (i.e., they left when the cost of leaving was 20 EMU and stayed when the cost of leaving was 0 EMU), and five participants who did both.

INCENTIVES Participants’ decisions were incentivized, with the potential to earn up to £5.00 based on their decisions. If participants correctly predicted the total number of EMU that

attackers would contribute to their conflict pool, they received a bonus of £1.00. To incentivize the Intergroup Attacker-Defender Contest with Exit, half of the participants were randomly

assigned to the defender role, while the other half was assigned to the attacker role. Thereafter, participants were randomly divided into groups of six, consisting of three defenders and

three attackers. Once the groups were formed, the cost of leaving was randomly determined for each group via a random number generator. For this cost of leaving, we implemented participants’

decisions. Participants could earn up to £4.00 (i.e., each EMU they received was worth £0.10). On average, participants received £1.04 (SD = 0.81, range: £0.0–2.5) for their choices in

study 1. STATISTICAL ANALYSES First, we compared the findings of study 1 to the Nash Equilibrium in mixed strategies in the IADC-NE6. Taking the groups as units, each being endowed with 20 ×

3 = 60 EMU, and assuming individuals are risk-neutral rational selfish payoff maximizers, the strategies played in the Nash Equilibrium imply an average contribution of 7.25 EMU to in-group

defense, defender success in 62.5% of rounds, and an expected earnings of 11.4 EMU28. These numbers are based on identifying the symmetric mixed-strategy equilibrium of a six-player game

(three attackers against three defenders) with individual endowments between 2 and 15 extrapolated to endowment levels of 20. Second, we compared stay-or-leave decisions to prior data. Past

IADC-NE studies revealed varying earnings for defenders: 7.63 (72 participants in study 1)6, 5.72 (66 participants in study 2)6, 4.26 (105 participants)29, and 7.59 EMU (80 participants)30.

We calculated a weighted average with regards to defenders’ earnings based on the sample size of each study with Eq. (1). $$\bar{E}=\frac{7.63\times 72\,+\,5.72\times 66\,+\,4.26\times

105\,+\,7.59\times 80}{72\,+\,66\,+\,105\,+\,80\,}=6.13$$ (1) Thus, based on previous data, defenders are expected to earn 6.13 EMU when deciding to stay in conflict. Finally, we fit a

maximum likelihood model to defenders’ stay-or-leave decisions to investigate how much they discount the stay option. Akin to risk-aversion models48, we modeled discounting of staying with a

power-function (20_α_). Hence, our model assumes that, for each stay-or-leave decision, participants compare the value of leaving (20 minus costs) with the expected value of staying

(20_α_), where _α_ is the individual’s discount rate of staying. Since decisions are binary, the (expected) values are transformed by a soft-max function to receive (predicted) values for

choosing to stay-or-leave, given cost (_c_) via Eq. (2). $$p\left({\mbox{stay|}}c\right)=\frac{{e}^{\phi \times {20}^{\alpha }}}{{e}^{\phi \times {20}^{\alpha }}+{e}^{\phi \times (20-c)}}$$

(2) The two free parameters _α_ and ϕ were estimated for each individual separately, using maximum likelihood. Average _α_ was estimated at 0.82 (SD = 0.18). INTERACTIVE BEHAVIORAL STUDIES 2

AND 3 PARTICIPANTS AND ETHICS Both studies were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology at Leiden University (study 2: 2021-12-23-C.K.W. de Dreu-V1-3642, study 3:

2022-06-07-C.K.W. de Dreu-V1-4063). Both studies were programmed in oTree (version 3.4.0)49 written in Python (version 3.7.9.). Participants were recruited at Leiden University (The

Netherlands; _n_ = 240 per study; study 2: 71% were female, study 3: 77% were female; sample size was determined based on previous research, no statistical method was used to predetermine

sample size). No participants were excluded, and both studies did not involve any deception. Participants were between 17 and 49 years of age (study 2: M = 22.20, SD = 3.66, study 3: M =

21.25, SD = 3.67), provided informed consent, and received full debriefing after participating. They received a standard fee of €5.00 or 2 course credits for participation, and their

decisions were fully incentivized (see Incentives section for details). Participation took ~60 min. STUDY DESIGNS In each experimental session of study 2, six individuals were invited and

randomly assigned to one of the individual cubicles within the laboratory. Participants read the information letter and signed the informed consent once seated. After giving informed

consent, participants were instructed that their decisions, and those of other participants, would influence both their own payment and that of others. Participants first completed the

social value orientation slider measure19 to measure their social preferences. In this measure, participants decide how to allocate EMU between themselves and an unknown other person. EMU

could be allocated self-servingly or pro-socially (sacrificing EMU to benefit the other person). Based on the decision pattern, participants can be classified as prosocial or selfish. This

was followed by the iterative multiple price list task31 to measure participants’ risk preferences. In this task, participants were presented with five choices between a guaranteed payment

and a lottery. The lottery offered a 50% chance of receiving 300 EMU and a 50% chance of receiving 0 EMU. While the lottery remained consistent across all decisions, the guaranteed payment

varied based on participants’ choices. That is, selecting the lottery resulted in an increased guaranteed payment for the subsequent choice, whereas opting for the guaranteed payment led it

to subsequently decrease. Participants then read instructions for the Intergroup Attacker-Defender Contest with Exit (Fig. 1) from the perspective of their (randomly) assigned group role

(either attacker or defender). After the rules of the task were explained, participants answered 14 practice questions to probe their understanding of the task. Only after all practice

questions were answered correctly, participants could continue with the task. The task consisted of four blocks and each block consisted of ten rounds. At the start of each new round,

participants received 20 EMU. Thereafter, all defenders could decide if they wanted to leave. If defenders left, they evaded the attack by the other group. However, defenders had to pay a

cost to leave that was deducted from their 20 EMU (their endowment). There were three blocks in which the cost of leaving was manipulated. These costs of leaving were 5, 7 (in line with the

mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium for individual defender contributions6), or 10 EMU (in line with the Nash equilibrium for defender contributions when treating groups as single agents6).

There was also one block in which leaving was not possible (i.e., our baseline condition), to be able to compare results to the original attacker-defender game6. The order of blocks was

counterbalanced across groups. Once all defenders had made their decision, everyone was informed how many defenders left. If everyone in the defender group decided to leave, there was no

possibility to contribute to one’s group’s conflict pool C. Consequently, everyone in the defender group earned 20 EMU (their endowment) minus the cost of leaving (L), while attackers

retained their 20-EMU endowment. If at least one defender stayed, the defenders who stayed (d) and all attackers simultaneously determined their individual contributions (g) to their group’s

conflict pool C, with 0 ≤ gi ≤ 20. Individual contributions to the conflict pool were wasted meaning that these could never be earned back, but when Cattacker > Cdefender, the attackers

won the remaining EMU of the defenders who stayed (d × 20 − Cdefender). These spoils of conflict were divided equally among the attackers and added to the attackers’ remaining endowments (20

− gi). Defenders who stayed thus earned nothing when attackers won. However, when Cattacker ≤ Cdefender, defenders who stayed defended themselves successfully. In this case, both attackers

and defenders earned their remaining endowments (20 − gi). Thus, individual contributions in attacker (defender) groups reflected out-group aggression (in-group defense). At the end of each

round, all participants were informed about the total contribution their group made to their conflict pool, the total contribution made by the other group to their conflict pool, and

everyone’s resulting earnings. With regards to this, participants were identifiable such that participants of both groups knew which specific individuals in the defender group left and knew

how much everyone (from both groups) earned. Before the start of each block, participants in study 2 were asked to predict the decisions of others. In the blocks in which defenders could

leave, participants were asked to predict how many defenders would, on average, leave per round. When leaving was not possible, participants predicted how many EMU both groups would, on

average, contribute to their conflict pool per round. At the end of each block, participants were asked how close, bonded, committed, and how much solidarity they felt towards members of

their own group on a scale from 1 to 7. Because ratings exhibited good internal consistency, we aggregated ratings into one single score representing ingroup solidarity (Cronbach’s _α_ =

0.897 for study 2, and 0.911 for study 3). Following the Intergroup Attacker-Defender Contest with Exit, participants filled in their demographics (age, gender, education, study field,

country). Finally, participants were informed about their earnings and debriefed. Study 3 was similar to study 2, with a few exceptions. First, in study 3, the cost of leaving was fixed to 5

EMU. Second, between blocks, we manipulated how many defenders could leave (order counterbalanced across groups); either no defenders could leave, one defender could leave, two defenders

could leave, or all defenders could leave. Leaving abilities were fixed within blocks (i.e., the same person could (not) leave). To minimize reciprocity concerns between blocks, leaving

abilities were also kept constant across blocks: the defender who could leave when only one defender could leave also could leave when two defenders could leave, and vice versa for defenders

who could not leave. Finally, we did not ask participants to predict the decisions of others in study 3. INCENTIVES Participants’ decisions were incentivized, such that they could earn up

to €21.50 based on their decisions in study 2, and up to €19.00 euros in study 3. In both studies, participants could (1) earn EMU in the social value orientation slider measure19, (2) earn

EMU in the iterative multiple price list task31 (our risk preference measure), and (3) earn EMU in the Intergroup Attacker-Defender Contest with Exit. In study 2, participants could also

earn EMU (4) by correctly guessing the decisions of other participants. Earnings were paid out via bank transfer immediately after the study. First, to incentivize participants’ decisions

using the social value orientation slider measure19, participants were randomly paired twice with another participant in their group (participants could maximally earn €1.50). The choices of

both pairs were incentivized, with each participant once being selected as the allocator and once as the receiver. On average, participants received €1.28 (SD = 0.08, range: €1.07–1.43) for

their choices in study 2, and €1.28 (SD = 0.07, range: €1.01–1.47) for their choices in study 3. Second, to incentivize participants’ decisions in the iterative multiple price list task31,

one of their choices was picked to determine their payoff (participants could maximally earn €1.50). If participants chose the lottery, a random draw determined whether the high outcome

would constitute their payoff. Otherwise, the sure payment would constitute their payoff. On average, participants received €0.75 (SD = 0.56, range: €0.00–1.46) for their choices in study 2,

and €0.71 (SD = 0.53, range: €0.00–1.46) for their choices in study 3. Third, in the Intergroup Attacker-Defender Contest with Exit, participants were paid out based on the average of 8

randomly selected rounds (i.e., 2 decisions per block; participants could maximally earn €16.00). In both studies, each EMU that participants received was worth €0.05. On average, they

earned €5.78 (SD = 1.97, range: €2.00–10.00) for their choices in study 2, and €5.76 (SD = 2.08, range: €1.00–11.00) for their choices in study 3. Finally, in study 2, we compared

participants’ expectations with the actual, average, contributions (when leaving was not possible) and leaving frequency (when leaving was possible). For each correct expectation,

participants received €0.50 and could maximally earn €2.50. Participants received, on average, €0.71 (SD = 0.50, range: €0.00–2.00). PRE-REGISTRATIONS We pre-registered the experimental

design, analysis plan, sample size, and exclusion criteria of study 2 via AsPredicted (on February 2nd, 2022; #87718, https://aspredicted.org/7wk4m.pdf). There were no deviations from our

pre-registration. With regards to the frequency of leaving, we pre-registered that (i) defenders would leave more frequently when the costs of leaving were low rather than high, and that

(ii) defenders would leave more frequently when others in their group left as well. With regards to defender contributions, we pre-registered that (iii) defenders would contribute more to

conflict when there was no possibility to leave (compared to when leaving was possible), and that (iv) defenders would contribute more to conflict when the leaving costs were high rather

than low. Finally, with regards to attacker contributions, we pre-registered that (v) when more defenders left, attackers would contribute less to conflict, but with a higher success rate

for winning the conflict round, and vice versa. For study 3 we also pre-registered the experimental design, analysis plan, sample size, and exclusion criteria via AsPredicted (on September

26th, 2022, #107875, https://aspredicted.org/sh8x7.pdf). There were no deviations from our pre-registration. With regards to the frequency of leaving, we pre-registered that (i) under

asymmetric leaving abilities (i.e., when only some defenders, but not all, could leave), defenders, who could leave, would leave relatively less frequently compared to when all defenders

could leave. With regards to defender contributions, we pre-registered that (ii) under asymmetric leaving abilities, defenders, who could not leave, would contribute more to conflict

compared to a situation in which all defenders could not leave. In contrast, defenders, who could leave, were expected to contribute less to conflict compared to a situation in which all

defenders could not leave. Furthermore, (iii) when all defenders could leave, we expected contributions to conflict to be lower than when some or all defenders could not leave. Finally, with

regards to defender ingroup solidarity, we pre-registered that (iv) a higher leaving rate would result in a lower self-reported ingroup solidarity. STATISTICAL ANALYSES Statistical models

were fitted using the lme4 package in R50 (version 4.0.3.). Multilevel (logistic) models included random intercepts for participants nested within their group to account for violations of

independence, since participants made repeated decisions and were part of a group in which they potentially influenced each other’s decisions over time. All reported statistical tests were

two-tailed. We did not correct for multiple testing, as we did not test multiple contrast within models. For all models reported we checked assumptions. Assumptions were met for most models.

If assumptions were not met, we still used multilevel models, as these were most appropriate for our data structure and have been found to be robust to violations of distributional

assumptions51. Complete results for all regression models can be found in the Supplementary Information. For study 2, we fit multilevel (logistic) regression models to examine how giving

defenders the option to leave under different costs impacted defender leaving (see Table S1), expectations about defenders’ willingness to leave (see Table S2), group-level contributions to

conflict (see Tables S3 and S4), defenders’ individual-level contributions to conflict (see Table S5), defender success (see Table S6), defender earnings (see Tables S7 and S8), and ingroup

solidarity (see Table S9). For study 3, we also fit multilevel (logistic) regression models to examine how asymmetric leaving opportunities impacted defender leaving (see Tables S10 and

S11), defenders’ individual-level contributions to conflict (Tables S12–S14), defender success (see Table S15), defender earnings (see Tables S16–S19) and ingroup solidarity (see Table S20).

REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY The data of our experiment are

publicly available in an OSF repository (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5SWXK)52. There are no restrictions to accessing the data. CODE AVAILABILITY The experiment and analysis code are

publicly available in the same OSF repository (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5SWXK)52. REFERENCES * Crippa, A., d’Agostino, G., Dunne, J. & Pieroni, L. Conflict as a Cause of

Migration. _Oxford Econ. Pap. 1–23_ (Oxford Economic Papers, 2024). * Gochman, C. S. & Maoz, Z. Militarized interstate disputes, 1816-1976: procedures, patterns, and insights. _J. Confl.

Resolut._ 28, 585–616 (1984). Article Google Scholar * De Dreu, C. K. W. & Gross, J. Revisiting the form and function of conflict: neurobiological, psychological and cultural

mechanisms for attack and defense within and between groups. _Behav. Brain Sci._ 42, e116 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Albrecht, H. & Koehler, K. Going on the run: what drives

military desertion in civil war? _Secur. Stud._ 27, 179–203 (2018). Article Google Scholar * McLauchlin, T. Desertion and collective action in civil wars. _Int. Stud. Q._ 59, 669–679

(2015). Google Scholar * De Dreu, C. K.W. et al. In-group defense, out-group aggression, and coordination failures in intergroup conflict. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA_ 113, 10524–10529

(2016). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhang, H., Yang, J., Ni, J., De Dreu, C. K. W. & Ma, Y. Leader–follower behavioural coordination and neural

synchronization during intergroup conflict. _Nat. Hum. Behav._ 7, 2169–2181 (2023). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rusch, H. Modelling behaviour in intergroup conflicts: a review of

microeconomic approaches. _Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B_ 377, 20210135 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Sheremeta, R. M. Behavior in group contests: a review of experimental research.

_J. Econ. Surv._ 32, 683–704 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Dechenaux, E., Kovenock, D. & Sheremeta, R. M. A survey of experimental research on contests, all-pay auctions and

tournaments. _Exp. Econ._ 18, 609–669 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Böhm, R., Rusch, H. & Baron, J. The psychology of intergroup conflict: a review of theories and measures. _J.

Econ. Behav. Organ._ 178, 947–962 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Rusch, H. The two sides of warfare. _Hum. Nat._ 25, 359–377 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Glowacki, L. &

McDermott, R. Key individuals catalyse intergroup violence. _Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B_ 377, 20210141 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Wrangham, R. W. & Glowacki, L. Intergroup

aggression in chimpanzees and war in nomadic hunter-gatherers: evaluating the chimpanzee model. _Hum. Nat._ 23, 5–29 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A.

Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. _Econometrica_ 47, 263–291 (1979). Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Chowdhury, S. M., Jeon, J. Y. & Ramalingam, A. Property

rights and loss aversion in contests. _Econ. Inq._ 56, 1492–1511 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Mayoral, L. & Ray, D. Groups in conflict: private and public prizes. _J. Dev. Econ._

154, 102759 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Leach, C.W. et al. Group-level self-definition and self-investment: a hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification. _J. Pers.

Soc. Psychol._ 95, 144–165 (2008). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Murphy, R. O., Ackermann, K. A. & Handgraaf, M. J. J. Measuring social value orientation. _Judgm. Decis. Mak._ 6,

771–781 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Rusch, H. Heroic behavior: a review of the literature on high-stakes altruism in the wild. _Curr. Opin. Psychol._ 43, 238–243 (2022). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Rusch, H. Asymmetries in altruistic behavior during violent intergroup conflict. _Evolut. Psychol._ 11, 973–993 (2013). Article Google Scholar * De Dreu, C. K.

W., Shalvi, S., Greer, L. L., Van Kleef, G. A. & Handgraaf, M. J. J. Oxytocin motivates non-cooperation in intergroup conflict to protect vulnerable in-group members. _PLoS ONE_ 7,

e46751 (2012). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * De Dreu, C. K. W. et al. The neuropeptide oxytocin regulates parochial altruism in intergroup conflict among humans.

_Science_ 328, 1408–1411 (2010). Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Marsh, N., Marsh, A. A., Lee, M. R. & Hurlemann, R. Oxytocin and the neurobiology of prosocial behavior.

_Neuroscientist_ 27, 604–619 (2021). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fehr, E. & Fischbacher, U. The nature of human altruism. _Nature_ 425, 785–791 (2003). Article ADS CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Tomasello, M. & Vaish, A. Origins of human cooperation and morality. _Annu. Rev. Psychol._ 64, 231–255 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rand, D. G.

& Nowak, M. A. Human cooperation. _Trends Cogn. Sci._ 17, 413–425 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Méder, Z. & Snijder, L. L. _Group Attacker-Defender Equilibrium

Calculations_ https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/KZEAB (2024). * De Dreu, C. K. W., Gross, J. & Reddmann, L. Environmental stress increases out-group aggression and intergroup conflict in

humans. _Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B_ 377, 20210147 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Gross, J., De Dreu, C. K. W. & Reddmann, L. Shadow of conflict: how past conflict influences

group cooperation and the use of punishment. _Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process._ 171, 104152 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Andersen, S., Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I. & Rutström, E.

E. Elicitation using multiple price list formats. _Exp. Econ._ 9, 383–405 (2006). Article Google Scholar * De Dreu, C. K. W. & Triki, Z. Intergroup conflict: origins, dynamics and

consequences across taxa. _Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B_ 377, 20210134 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Thielmann, I. & Böhm, R. Who does (not) participate in intergroup conflict?

_Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci._ 7, 778–787 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Eriksson, T., Teyssier, S. & Villeval, M. Self‐selection and the efficiency of tournaments. _Econ. Inq._ 47,

530–548 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Dohmen, T. & Falk, A. Performance pay and multidimensional sorting: productivity, preferences, and gender. _Am. Econ. Rev._ 101, 556–590

(2011). Article Google Scholar * Anderson, L. R. & Stafford, S. L. An experimental analysis of rent seeking under varying competitive conditions. _Public Choice_ 115, 199–216 (2003).

Article Google Scholar * Olson, M. & Zeckhauser, R. An economic theory of alliances. _Rev. Econ. Stat_. 48, 266–279 (1966). * Herbst, L., Konrad, K. A. & Morath, F. Endogenous

group formation in experimental contests. _Eur. Econ. Rev._ 74, 163–189 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Weisel, O. & Shalvi, S. The collaborative roots of corruption. _Proc. Natl.

Acad. Sci. USA_ 112, 10651–10656 (2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gross, J. & De Dreu, C. K. W. Rule following mitigates collaborative cheating and

facilitates the spreading of honesty within groups. _Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull._ 47, 395–409 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Capraro, V. & Perc, M. Mathematical foundations of

moral preferences. _J. R. Soc. Interface_ 18, 20200880 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Curry, O. S., Mullins, D. A. & Whitehouse, H. Is it good to cooperate?

Testing the theory of morality-as-cooperation in 60 societies. _Curr. Anthropol._ 60, 47–69 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Tajfel, H., Turner, J. C., Austin, W. G. & Worchel, S. An

integrative theory of intergroup conflict. _Organ. Identity_ 56, 9780203505984–16 (1979). Google Scholar * Morrow, J. D. Capabilities, uncertainty, and resolve: a limited information model

of crisis bargaining. _Am. J. Pol. Sci_. 33, 941–972 (1989). * Fearon, J. D. Rationalist explanations for war. _Int. Organ._ 49, 379–414 (1995). Article Google Scholar * Massey, D. S.

& Aysa-Lastra, M. Social capital and international migration from Latin America. _Int. J. Popul. Res_. 2011, 1–18 (2011). * Massey, D. S. & Espinosa, K. E. What’s driving Mexico-US

migration? A theoretical, empirical, and policy analysis. _Am. J. Sociol._ 102, 939–999 (1997). Article Google Scholar * Laibson, D. Life-cycle consumption and hyperbolic discount

functions. _Eur. Econ. Rev._ 42, 861–871 (1998). Article Google Scholar * Chen, D. L., Schonger, M. & Wickens, C. oTree—an open-source platform for laboratory, online, and field

experiments. _J. Behav. Exp. Financ._ 9, 88–97 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. M. & Walker, S. C. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4.

_J. Stat. Softw._ 67, 1–48 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Schielzeth, H. et al. Robustness of linear mixed‐effects models to violations of distributional assumptions. _Methods Ecol.

Evol._ 11, 1141–1152 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Snijder, L. L., Gross, J., Stallen, M. & De Dreu, C. K. W. _Prosocial Preferences and Solidarity Escalate Intergroup Conflict by

Prioritizing Fight Over Flight_ https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5SWXK (2024). Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Z. Méder for providing the game-theoretic analysis of the

attacker-defender game. We thank M. Andrikopoulou, M. C. Popa, and M. Tjoeng for assistance with data collection. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC)

under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (AdG agreement no. 785635) to C.K.W.D.D., the Spinoza Award from the Netherlands Science Foundation (NWOSPI-57-242)

to C.K.W.D.D., a Starting Grant (StG agreement, SBFI Nr. MB23.0003) to J.G., and a VENI Award from the Netherlands Science Foundation (NWO 016.Veni.195.078) to J.G. AUTHOR INFORMATION

AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Social, Economic and Organisational Psychology, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands Luuk L. Snijder & Mirre Stallen * Department of Psychology,

University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Jörg Gross * Poverty Interventions, Center for Applied Research on Social Sciences and Law, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands Mirre Stallen * Faculty of Behavioral and Social Sciences, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands Carsten K. W. De Dreu * Faculty of Economics and Business,

University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands Carsten K. W. De Dreu * Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology Unit, German Primate Center, Leibniz Institute for Primate Research,

Göttingen, Germany Carsten K. W. De Dreu Authors * Luuk L. Snijder View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jörg Gross View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mirre Stallen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Carsten K. W. De Dreu View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS L.L.S., J.G., M.S., and C.K.W.D.D. conceived of the project and designed the studies. L.L.S.

programmed the experiment and coordinated data collection. L.L.S. and J.G. analyzed data with input from M.S. and C.K.W.D.D. L.L.S. drafted the manuscript and incorporated co-author

revisions. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Luuk L. Snijder. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. PEER REVIEW PEER REVIEW INFORMATION

_Nature Communications_ thanks Valerio Capraro and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available. ADDITIONAL

INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY

INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International

License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the

source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived

from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line

to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS

ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Snijder, L.L., Gross, J., Stallen, M. _et al._ Prosocial preferences can escalate intergroup conflicts by countering selfish motivations to leave. _Nat Commun_ 15,

9009 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53409-9 Download citation * Received: 11 December 2023 * Accepted: 08 October 2024 * Published: 18 October 2024 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53409-9 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative