- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Biocompatible polymers are widely used in tissue engineering and biomedical device applications. However, few biomaterials are suitable for use as long-term implants and these

examples usually possess limited property scope, can be difficult to process, and are non-responsive to external stimuli. Here, we report a class of easily processable polyamides with

stereocontrolled mechanical properties and high-fidelity shape memory behaviour. We synthesise these materials using the efficient nucleophilic thiol-yne reaction between a dipropiolamide

and dithiol to yield an α,β − unsaturated carbonyl moiety along the polymer backbone. By rationally exploiting reaction conditions, the alkene stereochemistry is modulated between 35–82%

_cis_ content and the stereochemistry dictates the bulk material properties such as tensile strength, modulus, and glass transition. Further access to materials possessing a broader range of

thermal and mechanical properties is accomplished by polymerising a variety of commercially available dithiols with the dipropiolamide monomer. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS ONE

REACTION TO MAKE HIGHLY STRETCHABLE OR EXTREMELY SOFT SILICONE ELASTOMERS FROM EASILY AVAILABLE MATERIALS Article Open access 18 January 2022 STIFF AND SELF-HEALING HYDROGELS BY POLYMER

ENTANGLEMENTS IN CO-PLANAR NANOCONFINEMENT Article Open access 07 March 2025 CHEMICAL SYNTHESES OF BIOINSPIRED AND BIOMIMETIC POLYMERS TOWARD BIOBASED MATERIALS Article 05 October 2021

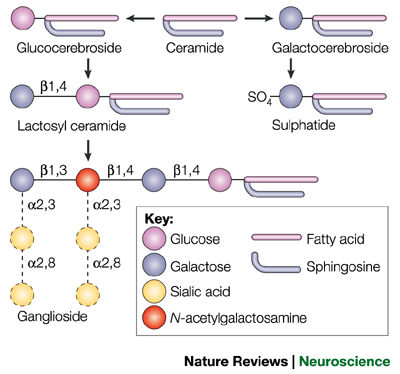

INTRODUCTION The ability to rationally modulate the thermomechanical properties of polymeric materials by design is a fundamental aim of materials science. It is well known that

stereochemistry of polymers dictates their bulk properties, but the importance of stereocontrol in polymer synthesis is often overlooked. For example, the naturally occurring isomers of

polyisoprene—natural rubber and gutta-percha—display stereochemically dependent thermomechanical properties where the _cis_ orientation of the alkene moiety disrupts chain packing and leads

to a much softer, more amorphous material1,2. Such striking structure–property relationships are often found in stereochemically precise biopolymers, e.g., collagen or elastin, but there

remain significant limitations in synthetically mimicking these complex biological materials3,4. Achieving control over stereochemical assembly of monomers into synthetic polymers,

particularly backbone stereochemistry, could afford a simple platform from which to access a diverse range of materials properties. This is of particular importance when considering the

unique mechanical needs of biomaterials operating in diverse physiological environments5,6. Synthetic polymers have been used in medical devices for more than five decades, and key recent

advances have largely focused on the development of biodegradable (or resorbable) materials for tissue engineering7. As such, the continued innovation of long-lasting non-resorbable polymers

in joint and/or bone therapies, for example, are lagging behind and suffer from notable limitations such as wear, difficult processing, sterilisation or high cost. Nevertheless, polyamides

have been a biomaterial of choice for decades and they have been extensively developed for applications ranging from use as sutures8,9 or membranes10 to vascular applications11 because of

their toughness, low cost and outstanding biocompatibility12. Polyamides are also widely used in bone engineering as a consequence of the materials’ high strength and flexibility, which is

due to the extensive degrees of both crystallinity and hydrogen bonding13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Even though this may be useful in selected orthopaedic or vascular applications, these

types of materials are typically difficult to process and functionalise, which has ultimately limited their performance in other applications. An ideal durable biomaterial platform would

incorporate the thermomechanical and biological performance of polyamides while displaying enhanced processability and advanced functionality, such as shape memory, for minimally invasive

device designs. We set out to create a tough, resilient biomaterial with stereochemically dependent properties by combining a polyamide backbone with unsaturated alkene moieties. Synthetic

heteroatom-containing polymers featuring stereocontrolled unsaturated moieties along the main chain are not very abundant. Nonetheless, polyesters or poly(ester-amide)s22,23,24, prepared

with pre-defined stereochemical units, such as fumaric acid, have garnered attention as biomaterials25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. However, maleate-based materials have been notoriously hard

to prepare due to isomerization issues35,36 and, with the exception of a recent report37, only low-molecular-weight polymers have been isolated38,39, which reduces the durability of the

materials. Furthermore, stereochemistry has not been directly invoked in order to modulate properties in most of these examples. Synthetic polyamides possessing chiral centres are

comparatively abundant and well represented in the literature with the stereochemistry usually derived from the use of naturally occurring comonomers and/or precursors, such as

sugars40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48, amino acids49,50, tartaric acid51,52,53 and terpenes54,55,56. A central feature among the stereo-defined polyamides is their inherent crystallinity, which

has been assessed in most instances. However, polymer mechanical properties and how those relate to stereochemistry are generally absent from these studies, presumably due to the challenges

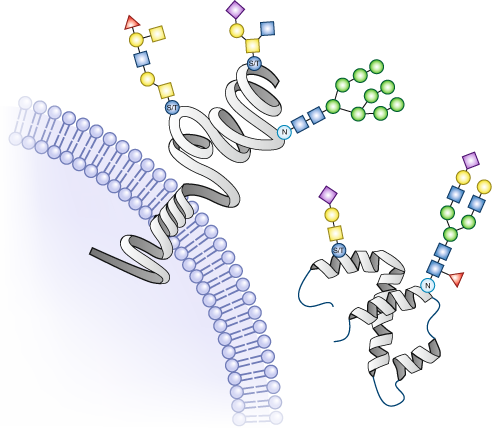

in synthesising high-molecular-weight step-growth polymers without implementing harsh reaction conditions. Herein, we explore the mild nucleophilic thiol-yne addition of dithiols to a

dipropiolamide monomer to produce stereocontrolled unsaturated polyamides possessing robust thermomechanical properties. The presence of both amide and unsaturated moieties along the

backbone imbue the materials with unique properties, namely shape-memory behaviour and stereochemically dependent thermomechanical properties. Moreover, the thiol-yne polyamides are

amorphous, with good optical transparency, and also exhibit elasticity at temperatures above the glass transition. These properties make the polymers unique among synthetic polyamides, such

as Nylons, which are semi-crystalline (when stretched) and display no shape-memory behaviour, factors which limit their utility as the medical device community begins to embrace minimally

invasive designs. All materials are cytocompatible and preliminary in vivo experiments indicate excellent biocompatibility, underscoring their potential as versatile biomaterials. RESULTS

SYNTHESIS OF STEREOCONTROLLED POLYAMIDES Recently, the nucleophilic Michael addition reaction between nucleophiles and activated alkynes (amino-yne, phenol-yne and thiol-yne) has attracted

considerable attention as an efficient path to step-growth polyesters57,58. There has been some progress in controlling the stereochemistry of the resultant alkene in the

backbone59,60,61,62,63,64,65, but many “yne-type” polymers are not synthesised in a stereocontrolled manner, despite the well-established impact of double-bond stereochemistry on bulk

material properties (e.g., glass transition and stiffness)60. Initially, we screened reaction conditions that were used for the analogous stereocontrolled reaction between thiols and

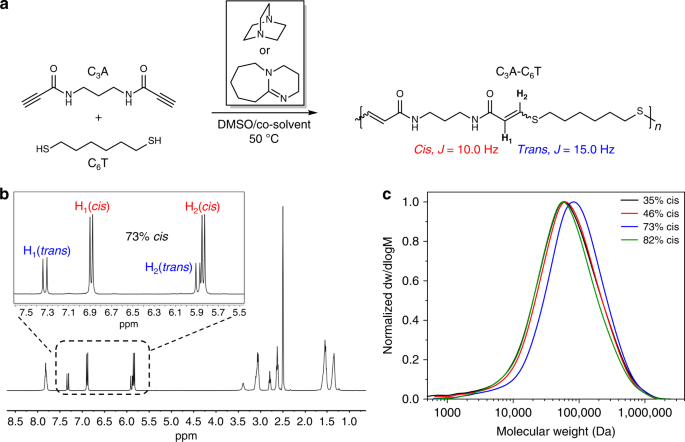

propiolate esters63. The combination of a dipropiolamide monomer (C3A) (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2), 1,6-hexanedithiol (C6T) and 1 mol% 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) in dimethyl

sulfoxide (DMSO) afforded a fibrous solid after isolation from the reaction mixture (Fig. 1a). After drying, the solid was analysed using 1H NMR spectroscopy and the product showed

characteristic vinyl proton resonances (73% _cis_) indicative of a thiol-yne addition (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). Finally, size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) confirmed high

molar mass polymers (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Fig. 20). Next, the stereochemistry of the vinyl thioether moiety in the polymer backbone was modified by changing either the polarity of the

reaction medium and/or the base catalyst60. Although DMSO was critical for polymer solubility, the overall polarity of the reaction mixture could be modulated to be less polar (dilution with

chloroform) or more polar (dilution with methanol). Qualitatively, the reaction between the propiolamide and thiol is sluggish compared with the propiolate analogue60, thus limiting the

choice of suitable base catalysts. A variety of organic bases were screened, including triethylamine (NEt3), only yielding oligomeric species. However, by employing

1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO) at higher loadings (10 mol%), we could isolate high molar mass polymers (_M_w ≥ 100 kDa) and we chose DABCO as the “weak” base (p_K_a (H-DABCO) = 8.8

versus, p_K_a (H-DBU) = _ca_. 12). Our initial reactions (using DBU and DMSO) afforded polymers with moderately high _cis_ content (_ca_. 70%) (Table 1, entry P2). The _cis_ content could be

increased by adding methanol to the DMSO/DBU reaction mixture (Table 1, entry P1; Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). To decrease the _cis_ content in the resultant polymers, progressively

greater amounts of chloroform were added to the DMSO reaction mixture, and DBU was substituted with DABCO (Table 1, entries P3–4; Supplementary Figs. 7–10). Additional propiolamide monomers

with longer methylene spacers (such as C4A, C5A and C6A) were active in the step-growth polyaddition reaction using our optimised conditions, but the resultant material would precipitate

from the reaction mixture as an intractable powder. Since we could not adequately characterise these polyamides because of their low processability, we excluded them from this study. THERMAL

AND MECHANICAL PROPERTIES The thermal properties of the materials were initially probed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and the degradation temperatures (_T_d) were ≥300 °C,

indicating excellent thermal stability (Supplementary Fig. S21). Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) of the polymers showed a broad glass transition (_T_g) and no discernible melt

transition (_T_m) (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 22). Nevertheless, the _T_g displayed a positive correlation with %_cis_ content as indicated by Δ_T_g = 14 °C between P4 (35% _cis_) and P1

(82% _cis_) (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 23). The thermal behaviour suggested that the materials were largely amorphous and surface imaging of P1 using atomic force microscopy (AFM) also

revealed a non-crystalline morphology (Supplementary Fig. 39). Prolonged annealing below and/or above the respective glass transition temperature also did not induce any crystallisation in

P1 (Supplementary Fig. 26). Repeated cycling of the polymers during thermal analysis also led to a decrease in modulus, which may have been due to undesirable cross-linking reactions or

possibly isomerization of the alkene moiety. However, according to 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis, negligible isomerization of the alkene (73 versus 71% _cis_) occurred after protracted

heating of a sample (_ca_. 12 h, 150 °C, N2 atmosphere) (Supplementary Fig. 19). It became clear that the properties of the unsaturated polyamides were very different from those of common

saturated polyamide analogues, such as Nylons, and it was perhaps most obvious when comparing their physical appearance (Fig. 2c). Variable temperature tensile testing of the high _cis_

polymer showed that as the polymer approached its glass transition temperature it softened significantly, with a concomitant improvement in ductility (Fig. 2d). To our surprise, when testing

the material above the glass transition temperature we observed elastomeric behaviour; this occurrence contrasts distinctly with the thermoplastic nature of Nylons under similar conditions

(Fig. 2e). However, the mechanical profiles of both classes of polyamides were comparable at ambient temperature (Supplementary Fig. 33). These results suggest that this class of

stereocontrolled, unsaturated polyamides can match the mechanical strength of Nylons, but with the added benefit of temperature-tuneable mechanical properties. As a control experiment, we

synthesised a Nylon 3,14 derivative in order to better model the composition of the C3A-C6T polymers. As expected, this polymer was similar to the commercial Nylons (and different to our

amorphous polyamide) as evidenced by its semi-crystalline nature (Supplementary Fig. 27). Further thermomechanical analysis of polymer films by dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) confirmed

the effect of the _cis_-_trans_ ratio on _T__g_. (Fig. 2f; Supplementary Fig. 28). Additional investigation of the mechanical properties for polymers with different stereochemistry was then

conducted. Overall, the polyamides possessed high moduli with moderate ductility. Specifically, the mechanical properties are comparable with Nylon 6,6, which is a useful biomaterial for

numerous applications. The Young’s modulus (_Ε_) of the materials ranged from 1052 ± 74 MPa (35% _cis_) to 1278 ± 42 MPa (82% _cis_), and stiffness increased accordingly with _cis_ content;

this trend was also very similar for glass transition temperature (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 31). It was found that there is a statistical difference (P < 0.05) between the elastic

moduli of materials with very high (≥73%) _cis_ content and those with low (≤46%) _cis_ content. However, the elastic moduli differences between the 35 and 46% _cis_ materials was found to

be statistically insignificant. An inverse relationship is generally true for plasticity where the lowest strain at break (_ε_break) was observed for P1 (_ε_break = 109 ± 28%). The strain at

break for P4 (_ε_break = 138 ± 87%) was not drastically different from P1 and was found to be statistically insignificant. However, it should be noted that the P4 trials were less

reproducible with one sample exceeding 200% elongation. The lack of reproducibility is also apparent when examining the relatively high standard deviations for the _Ε_ and _σ_stress (Table

1, entry P4). However, another sample with similarly high _trans_ content (37% _cis_) was much more reproducible and had a significantly higher strain at break albeit the molecular mass of

the sample was considerably greater (Supplementary Fig. 31). SHAPE MEMORY PROPERTIES Many implants would benefit from minimally invasive attributes to reduce surgical trauma and therefore

time to healing. Shape memory behaviour could potentially provide a minimally invasive route for implantation by reducing the material footprint during surgery and it may also increase the

implant’s resilience to certain deformations or damage. Although shape memory alloys have been developed for hard tissue applications, they are beset by long-term biocompatibility issues66,

and most shape memory polymers for biomedical use are more similar to soft biological tissues (e.g., hydrogels)67,68. The introduction of a more tuneable and dynamic non-resorbable

biomaterial possessing excellent biocompatibility and robust mechanical properties could be extremely useful to provide a fine degree of control over the material’s behaviour. We discovered

that all formulations displayed shape memory behaviour (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), a rare phenomenon in polyamides that has previously only been observed in thermoset materials24,69. An

important note to make is that these thermoplastics display good initial shape recovery, on par with cross-linked materials containing permanent net-points which help promote their original

shape structures. In our system, it is likely that these features are a result of robust chain entanglements (due to high-molecular-weight) and entropic free-energy contributions combined

with a high degree of hydrogen bonding among the amide moieties. We attempted to more precisely identify the origin of the shape memory behaviour by examining the surface morphology below

and above the _T_g of P1 using AFM; however, no significant micro- or nano-scale morphological changes were visible (Supplementary Fig. 39). We are still probing the molecular emergence of

the shape memory. Regardless of stereochemistry, full strain recovery and strain fixation were achieved (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 1). Following the trends revealed by thermomechanical

analysis, high _cis_ polymers displayed reduced strains (in line with the mechanical behaviour of the system). However, the high _cis_ polymers were also more likely to undergo shape

recovery when approaching the _T_g (at the increase of the dampening ratio as determined by tan _δ_), while the low _cis_ polymers required prolonged isothermal equilibrium at 120 °C (well

above the _T_g) to achieve full strain recovery (Fig. 3b). The slower recovery of the low _cis_ samples may be a consequence of the better polymer chain packing that is afforded by relative

abundance of hydrogen bonding around individual chains. On the other hand, high _cis_ polymers may have a decreased relative concentration of hydrogen bonding because of a more open

molecular structure, and therefore reduced interactions with surrounding carbonyl moieties. We also investigated the durability by performing cyclic shape memory experiments, including

examining differences that could result from stereochemistry as well as choice of thiol comonomer (Supplementary Figs. 29 and 30, Supplementary Table 3). Regardless of composition, shape

memory performance decreased after cycling (especially after ten cycles). This diminished cyclic repeatability in the shape memory behaviour is not unexpected for thermoplastic shape memory

materials and may also be attributable to fatigue in the macroscopic film. Importantly, potential medical applications that make use of shape memory behaviour to produce minimally invasive

devices do not require a material to behave as an actuator. Rather, a single shape-recovery response is necessary for minimally invasive surgeries. The performance of the polyamides

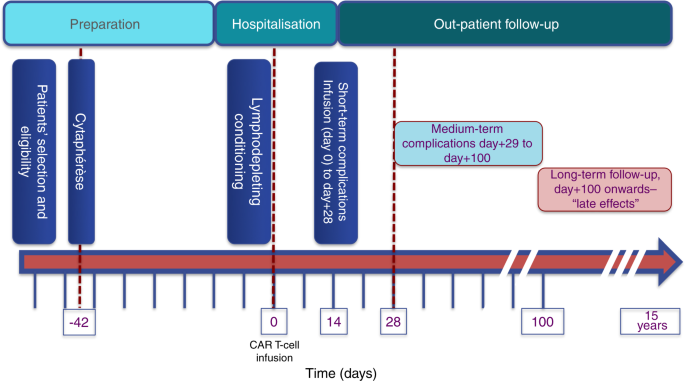

displayed here meet these criteria and could be suitable in such applications. BIOCOMPATIBILITY STUDIES Hydrolytic stability and water uptake behaviour were assessed for a high _trans_

sample (33% _cis_, _M_w = 109 kDa) and a high _cis_ sample (86% _cis_, _M_w = 123 kDa). The polymers were processed into disks via heated compression moulding, and the accelerated

degradation profiles were assessed in triplicate in PBS, 1 M KOH and 5 M KOH solutions at 37 °C (Supplementary Fig. 36). For both polymers, minimal degradation and slight swelling were

observed, irrespective of the medium, which indicated that this polymer class has robust hydrolytic stability. However, the swelling was more significant in the high _cis_ samples (135 ±

5.7%, 1 M KOH) compared with the high _trans_ samples (107 ± 4.4%, 1 M KOH). This trend is somewhat surprising since both materials are amorphous and have similar thermal profiles, but it is

consistent with the hypothesis that stereochemically dependent shape memory recovery behaviour results from the closeness of packing of the polymer chains in the bulk material. Regardless

of the medium, the high _trans_ materials initially swelled to a maximum water uptake after 10 days followed by a small decrease in mass (relative to maximum), but the high _cis_ materials

continued to swell throughout the duration of the study. These results indicate that stereochemistry also affects water uptake behaviour, and subsequently the overall hydrolytic stability,

which could also be leveraged in the future design of biomaterial devices and implants. In order to investigate the potential for use in biomaterial applications, a proliferation assay was

used as an initial method to determine cellular responses to all polyamides (C3A-C6T _cis_/_trans_, or P1 and P4, and high _cis_ polymers of other composition). Mouse osteoblasts (MC3T3-E1)

were cultured in cell culture medium containing 10% foetal bovine serum on thin discs of the polyamide or on the control polymer, poly(l-lactide) (PLLA). Cell proliferation was measured with

a PrestoBlue metabolic assay, after 1, 3 and 7 days of incubation. This cell line is generally considered as a suitable cell model for studying material cytocompatibility70,71,72. After 7

days, the number of cells on each sample had increased dramatically, indicating good cytocompatibility (Fig. 4a). Statistical analysis (_P_ < 0.05) revealed a superior cytocompatibility

of C3A-C6T _cis_ and C3A-C8T compared with the PLLA control, while C3A-DEGT was found to support cell proliferation less than PLLA. The in vivo biocompatibility of high _cis_ C3A-C6T (P1)

was subsequently examined over 8 weeks in murine subcutaneous implantation studies. Hematoxyclin and eosin staining (H&E staining) was used to detect fibrous capsule granuloma formation

and inflammatory cell presence, based upon ISO 10993-6 standards as assessor metrics, where individual slides were assessed for cell presence and numbers and assigned an inflammatory score

at the tissue-material interfacial region (Table 2). Comparisons to PLLA controls indicated that the selected polyamide was both biocompatible as well as biostable. PLLA is considered a gold

standard for implantable synthetic polymers and does not degrade over the time frame of the in vivo studies (8 weeks), hence we selected it as a suitable control for this experiment.

Moreover, the biocompatibility of nylons has long been established in a variety of different animal models73,74. Capsule formation in both species was found to be <200 µm and uncalcified,

which indicated that no severe inflammatory response occurred as a consequence of the presence of the material and is within the range of an accepted response for an implantable material

(Fig. 4b). The absence of necrosis was a further indication of the biocompatibility of this polymer system, and the reduced macrophage presence outside the tissue capsule indicated low

particulate formation and inflammation related to material degradation. The presence of macrophages at the implant-tissue interface was expected and provided evidence of implant site

healing. Similar macrophage loads at both the control and polyamide sites supported our claims of being a weakly immune-activating biomaterial, as PLLA is a well-known biomaterial used in a

wide variety of implantable materials/devices across multiple species. Both materials displayed inflammatory cell levels and species that were consistent with low level inflammation,

indicating good biocompatibility of the materials. We also investigated the in vivo stability of the materials by comparing post-implanted samples (at 4-week and 8-week time points) against

samples that had not been implanted. IR spectroscopic analysis of the samples indicated that the material composition was remarkably consistent before/after implantation as evidenced by the

absence of any changes to their absorption spectra (Supplementary Fig. 37). However, we noted changes in the 1H NMR spectra among the samples, particularly for the 8-week sample

(Supplementary Fig. 38). We observed new low-field proton resonances (_δ_ = 1.0 − 4.5), but these may be explained by histological processing techniques (i.e., incomplete rinsing or cleaning

of the sample). There were also minor variations in the vinylic resonance region (_δ_ = 7.0 − 7.5), suggesting some interaction or reactivity of the polymer in the biological media.

Nevertheless, the IR spectra and physical appearance remained nearly identical among the samples. Finally, we observed reasonable maintenance of mechanical properties when samples were

immersed in aqueous media as evidenced by immersion DMA experiments and tensile testing of “wet” samples (Supplementary Figs. 34 and 35). Together, these data suggest the materials are quite

stable in application settings. MODULATION OF MATERIAL PROPERTIES BY VARYING THIOL COMONOMER After examining the C3A-C6T polymers, other thiol comonomers were polymerised with C3A to

examine the effect that the thiol comonomer had on thermomechanical properties of the resultant polymers (Table 3; Supplementary Figs. 11–20, Supplementary Notes 1–4). In order to control

for the effects of stereochemistry, all polymers were targeted for high _cis_ content (_ca_. 80%) using the conditions for the synthesis of P1 (Table 1, entry P1). Differential scanning

calorimetry (DSC) of the high _cis_ polymers also revealed the absence of a _T_m, similar to P1-4 (Supplementary Fig. 24). Nevertheless, the _T_g displayed a positive correlation with %

_cis_ content. Unsurprisingly, as the number of carbon atoms increased in the thiol moiety (C3, C6, C8 and C10) the _T_g decreased (Fig. 5b; Supplementary Fig. 25). The mechanical properties

(such as _Ε_ and σstress) followed a similar trend and these differences among samples were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5a; Supplementary Fig. 32). However, as

the linker length increased the ductility of the materials also greatly improved (C3A-C3T, _ε_break = 24 ± 3% versus C3A-C10T, _ε_break = 313 ± 19%) and these differences were statistically

significant as well. Importantly, no significant differences in shape-memory behaviour, either the strain fixation or the recovery stress, were observed among the compositions

(Supplementary Table 2). The most interesting mechanical properties were displayed by the C3A-CDEGT polymer, which incorporated ethers in the repeat unit. The introduction of the diethylene

glycol moiety into the polymer backbone resulted in a material with the lowest _T_g and we predicted this would lead to softer, yet more ductile material (Fig. 5b). In fact, C3A-CDEGT was

more ductile (_ε_break = 318 ± 70%) than other materials and was found to be statistically different (P < 0.05) from all compositions except for C3A-C10T. But remarkably, it also

possessed the greatest modulus (_Ε_ = 1623 ± 77 MPa) and yield stress (78.1 ± 2.4 MPa) for the entire polyamide series (Supplementary Table 4), although these values are not statistically

different from the C3T or C6T polymers. A similar enhancement of mechanical properties has previously been observed in poly(ether-thioureas) as compared to poly(alkyl-thioureas)75. The

authors proposed that the extra H-bond acceptors (ethereal oxygen atoms) increased the H-bonding interactions between the polymer chains without inducing crystallisation. Our results further

suggest that incorporating ethereal oxygen atoms into polymers displaying significant hydrogen bonding (e.g., polyamides or polythioureas) may present a path to processable materials with

high toughness. Furthermore, by decreasing the _T_g, the transition temperature of the shape memory was closer to a biologically compatible temperature (Supplementary Fig. 28 and

Supplementary Table 2). DISCUSSION In conclusion, the nucleophilic thiol-yne addition was exploited to synthesise a family of stereochemically controlled polyamides. The thermomechanical

properties were tuned either by modulating the stereochemistry of the alkene moiety in the backbone or changing the thiol comonomer. Materials with high _cis_ content were stiffer and less

ductile than high _trans_ polymers, but this was not correlated with crystallinity since all polymers appeared to be amorphous. In vitro cytocompatibility and in vivo assessments indicated

that these materials possess excellent stability and biocompatibility, which suggests that they could serve as adaptive, non-resorbable biomaterials. Nylons have traditionally been some of

the most versatile biomaterials due to material property tuning which may be achieved solely through compositional adjustment; however, the system presented offers multiple possibilities for

precise property modulation. Our polyamides have comparable mechanical performance to nylons but are strikingly more adaptive and easier to process. The unique combination of biostability

and modifiable thermomechanical properties, in addition to the aging behaviours revealed during shape-memory testing, open avenues to durable biomedical devices such as arterial grafts,

heart valves and sewing cuffs. In these applications, the tuneable mechanical properties of the materials presented here, along with their stability, would allow for consistent, life-long

performance after implantation. METHODS GENERAL All manipulations of air-sensitive compounds were carried out under a dry nitrogen atmosphere using standard Schlenk techniques. All

compounds, unless otherwise indicated were purchased from commercial sources and used as received. The following chemicals were vacuum distilled prior to use and stored in Young’s tapped

ampoules under N2: 1,3-propanedithiol (C3T) (Sigma-Aldrich, 99%), 1,6-hexanedithiol (C6T) (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥97%), 1,8-octanedithiol (C8T) (Alfa Aesar, 98%), 1,10-decanedithiol (C10T) (Alfa

Aesar, 95%), 2,2-(ethylenedioxy)diethanethiol (CDEGT: Sigma-Aldrich, 95%). All solvents for recrystallisation were used as received. All measurements were taken from distinct samples, unless

otherwise noted. SYNTHESIS OF DIPROPIOLAMIDE MONOMER (C3A) A 3-neck 500-mL round bottom flask fitted with a 100-mL dropping funnel was charged with 1,3-diaminopropane (19.5 mL, 232 mmol,

1.00 equiv) and 100 mL water. The solution was cooled to 0 °C using an ice bath and then methyl propiolate (40.0 g, 476 mmol, 2.05 equiv) was added over 30 min using a dropping funnel.

During the course of the addition, the mixture became slightly yellow and a precipitate formed. After the addition, the resultant mixture was stirred for a further 6 h at 0 °C. Note: we

observed undesirable by-products and lower reaction yields when the reaction temperature was _ca_. >5–10 °C. The precipitate was collected using vacuum filtration and washed with cold

water (5 × 25 mL) to afford a light-yellow solid. After drying on the benchtop at 22 °C for 24 h to remove water, the compound was purified by recrystallisation (cooling to −20 °C for _ca_.

16 h after heating) from a mixture of chloroform/methanol (5/1) to afford the title compound as a pale-yellow solid (13.9 g, 34%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO–_d_6) δ 8.69 (t, _J_ = 5.8 Hz, 2H),

*8.17 (t, _J_ = 5.4 Hz), *4.43 (s), 4.11 (s, 2H), *3.24 (q, _J_ = 6.8 Hz), 3.06 (q, _J_ = 6.6 Hz, 4H), 1.55 (p, _J_ = 7.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO–_d_6) δ 151.58, *81.27, 78.31,

75.54, 36.66, *36.36, *29.73, 28.27. * = minor signals due to rotamers. HRMS (ESI-TOF) (_m_/_z_): [M + H]+ calculated for C9H10N2NaO2, 201.0633; found, 201.0634. REPRESENTATIVE

POLYMERISATION OF C3A-C6T POLYMERS A 100-mL round bottom flask was charged with C3A (4.00 g, 22.4 mmol, 1.018 equiv) and a separate 20-mL scintillation vial was charged with C6T (3.31 g,

22.1 mmol, 1.000 equiv). The thiol was quantitatively transferred to the round bottom flask using DMSO (45 mL) for a final monomer concentration of ~0.5 M. The reaction mixture was placed in

a water bath (_ca_. 15 °C) and 1,8-diazabicyclo(5.4.0)undec-7-ene (DBU) (32.9 μL, 0.22 mmol, 0.01 equiv) was injected in one portion. The addition of DBU produced an exotherm which was

mitigated by heat transfer to the water bath. After 2 min of stirring, the reaction flask was sealed, removed from the bath and stirred at 50 °C in order to increase the solubility of the

polymer product. After 2 h the reaction was quenched with 1-dodecanethiol (0.5 mL, 2.1 mmol) to end-cap any alkyne chain-ends and stirred for 30 min. Then, the solution was diluted with DMSO

(_ca_. 50 mL) and BHT (0.5 g, 2.2 mmol) was added in order to prevent cross-linking during the precipitation step. The reaction mixture was then precipitated into methanol (1000 mL), and

the polymer was collected by decanting the supernatant. The polymer was stirred in methanol (200 mL) for _ca_. 12 h to help remove residual DMSO before drying in vacuo (500 mTorr) at 120 °C

overnight (_ca_. 16 h). GPC analysis (DMF + 5 mM NH4BF4) _M_p = 96.8 kDa, _M_w = 131.4 kDa, _M_n = 38.8 kDa, kDa, _Ð_m = 3.39. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO–_d_6) % cis = 73 δ 7.81 (t, _J_ = 5.7 Hz,

_cis_ + _trans_ overlapping, 2H), 7.32 (d, _J_ = 15.0 Hz, _trans_), 6.89 (d, _J_ = 10.1 Hz, _cis_ 2H), 5.89 (d, _J_ = 15.0 Hz, _trans_), 5.84 (d, _J_ = 10.0 Hz, _cis_ 2H), 3.14–3.02 (m,

_cis_ + _trans_ overlapping, 4H), 2.79 (t, _J_ = 7.3 Hz, _trans_), 2.63 (t, _J_ = 7.3 Hz, cis 4H), 1.64–1.47 (m, 6H), 1.43–1.28 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO–_d_6) δ 165.60_cis_,

163.71_trans_, 143.72_cis_, 139.25_trans_, 117.83_trans_, 115.81_cis_, 36.46_tran_, 36.23_cis_, 34.70, 31.05_trans_, 30.00_cis_, 29.42_cis_, 28.38_trans_, 27.64_trans_, 27.42_cis_. GENERAL

POLYMERISATION OF HIGH _CIS_ CONTENT POLYMERS A 100-mL round bottom flask was charged with C3A (4.00 g, 22.4 mmol, 1.018 equiv), and a separate 20 mL scintillation vial was charged with the

corresponding dithiol (22.1 mmol, 1.000 equiv). The dithiol was quantitatively transferred to the round bottom flask containing C3A by washing with DMSO (30 mL) and methanol (15 mL) for a

final monomer concentration of ~0.5 M. The reaction mixture was placed in a water bath (_ca_. 15 °C), and DBU (32.9 μL, 0.22 mmol, 0.01 equiv) was injected in one portion. The addition of

DBU produced an exotherm which was mitigated by heat transfer to the water bath. After 2 min of stirring, the reaction flask was sealed, removed from the bath and stirred at 50 °C in order

to increase the solubility of the polymer product. After 2 h, the reaction was quenched with 1-dodecanethiol (0.5 mL, 2.1 mmol) to end-cap any alkyne chain-ends and stirred for 30 min. Then,

the solution was diluted with DMSO (_ca_. 50 mL), and BHT (0.5 g, 2.2 mmol) was added in order to prevent cross-linking during the precipitation step. The reaction mixture was then

precipitated into methanol (1000 mL), and the polymer was collected by decanting the supernatant. The polymer was stirred in methanol (200 mL) for _ca_. 12 h to help remove residual DMSO

before drying in vacuo (500 mTorr) at 120 °C overnight (_ca_. 16 h). NMR SPECTROSCOPY NMR spectroscopy experiments were performed at 25 °C on a Bruker DPX-400 NMR instrument equipped

operating at 400 MHz for 1H (100.57 MHz for 13C). 1H NMR spectra are referenced to residual proton solvent (_δ_ = 2.50 for DMSO–_d__5_), and 13C NMR spectra are referenced to the solvent

signal (_δ_ = 39.52 for DMSO–_d__6_). The resonance multiplicities are described as s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet) or m (multiplet). MASS SPECTROMETRY High-resolution

electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry was performed on a Bruker MaXis Plus using a TOF detector in the Department of Chemistry, University of Warwick, CV4 7AL, UK. SIZE-EXCLUSION

CHROMATOGRAPHY (SEC) SEC measurements were performed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity II Multi-Detector GPC/SEC System fitted with RI and ultraviolet (UV) detectors (_λ_ = 309 nm) and PLGel 3 μm

(50 × 7.5 mm) guard column and two PLGel 5 μm (300 × 7.5 mm) mixed-C columns with DMF containing 5 mM NH4BF4 as the eluent (flow rate 1 mL/min, 50 °C). A 12-point calibration curve (_M_p =

550–2,210,000 g mol−1) based on poly(methyl methacrylate) standards (PMMA, Easivial PM, Agilent) was applied for determination of molecular weights. THERMOGRAVIMETRIC ANALYSIS (TGA) TGA

thermograms were obtained using a TGA/DSC 1-Thermogravimetric Analyzer (Mettler Toledo). Thermograms were recorded under an N2 atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1, from 50 to 500 °C,

with an average sample weight of _ca_. 10 mg. Aluminium pans were used for all samples. Decomposition temperatures were reported as the 5% weight loss temperature (_T_d 5%). MECHANICAL

PROPERTY MEASUREMENTS (FILM PREPARATION AND UNIAXIAL TENSILE TESTING) Thin films of each polymer were fabricated using a vacuum compression machine (TMP Technical Machine Products Corp.).

The machine was preheated to 170 °C. Then polymer was added into the 50 × 50 × 1.00-mm mould, and put into the compression machine with vacuum on. After 15 min of melting, the system was

degassed three times. Next, 10 lbs*1000, 15 lbs*1000, 20 lbs*1000, 25 lbs*1000 of pressure were applied consecutively for 2 min. each. After that, the mould was cooled down with 1000 psi of

pressure to prevent wrinkling of the film’s surface. The films were visually inspected to ensure that no bubbles were present in the films. Dumbbell-shaped samples were cut using a custom

ASTM Die D-638 Type V. The dimensions of the neck of the specimens were 7.11 mm in length, 1.70 mm in width and 1.00 mm in thickness. Tensile Tests were conducted at 10 mm min−1 using

dumbbell-shaped samples that were prepared using the method stated above. Tensile tests were carried out using an Instron 5543 Universal Testing Machine or Testometric M350-5 CT Machine at

room temperature (25 ± 1 °C), unless otherwise noted. The gauge length was set as 7 mm, and the crosshead speed was set as 10 mm min−1. The dimensions of the neck of the specimens were 7.11

mm in length, 1.70 mm in width and 1.00 mm in thickness. The elastic moduli were calculated using the slope of linear fitting of the data from strain of 0–0.1%. The reported results are

average values from at least three individual measurements unless otherwise specified. DIFFERENTIAL SCANNING CALORIMETRY (DSC) The thermal characteristics of the polymer thin films were

determined using differential scanning calorimetry (STARe system DSC3, Mettler Toledo) from 0 to 180 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 for three heating/cooling cycles unless otherwise

specified. The glass transition temperature (_T_g) was determined from the inflection point in the second heating cycle. DYNAMIC MECHANICAL ANALYSIS (DMA) Dynamic mechanical thermal analysis

(DMTA) data were obtained using a Mettler Toledo DMA 1-star system and analysed using the software package STARe V13.00a (build 6917). Thermal sweeps were conducted using bar-shaped films

(11.00 mm in length × 6.00 mm in width x 1.00 mm in thickness) cooled to −80 °C and held isothermally for _ca_. 5 minutes. Storage and loss moduli, as well as the loss factor (ratio of _E”_

and _E’_, tan δ), were probed as the temperature was swept from −80 to 150 °C, 2 °C min−1. Thermomechanical behaviour was determined for _n_ = 3 samples in this way. Shape-memory behaviour

of the same films was examined by first heating as-processed materials to 120 °C, holding samples isothermally for 8 min, and deforming samples using a 1 N load that was held static as the

sample was cooled again to ambient conditions (_ca_. 25 °C). Strain fixation was calculated as the strain held by the material as the load was released at ambient temperature. Deformed

samples were then heated at 10 °C min−1 up to 120 °C, where the samples were held isothermally for 20 min to allow for total shape recovery to take place. The temperature at which strain

recovery began was labelled as the recovery temperature, and the final recovered strain was the recoverable strain for the materials. Sample behaviour was averaged for _n_ = 3 films. CYCLIC

SHAPE MEMORY Performance evaluation was conducted using bar-shaped films (0.5 mm × 6 mm × 20 mm). The sample was first heated to 20 °C above the _T_g of the material, where samples were held

until equilibrated. At this point, the proximal film end was fixed, and its distal end was bent, with the film uniformly bent around a central shaft until the distal end was parallel to the

proximal. The sample was mechanically restrained to fix the film in this temporary shape until it had cooled to 22 °C. At this point, the mechanical constraint was removed, and strain

fixation was measured optically over a 5-min period. The sample was then heated to 20 °C above the _T_g of the material, where samples were held until equilibrated, with the shape recovery

measured optically at 5 s intervals. Final recovered strain was determined as a function of recovered deformation of the distal end compared with the fixed proximal end. This was repeated

for 60 cycles for each film, with _n_ = 3 films per examined species. ATOMIC FORCE MICROSCOPY (AFM) AFM was performed on a JPK Nanowizard 4 system fitted with a heater-cooler module to

control sample temperature (24–90 °C) during imaging. Images were acquired in the supplied acoustic enclosure and with vibration isolation, using a Nanosensor PPP-NCHAuD tip with a force

constant of around 42 N m−1. For data acquisition and handling Nanowizard Control and Data Processing Software V.6.1.117 in QI mode with a set point of 100 nN and pixel time of 8 ms was

used. In this mode, a force/distance curve is collected for each pixel in the acquired image. Adhesion was calculated by first subtracting the baseline from each force curve and then

identifying the lowest point of the retraction force curve. Slope, a proxy for the Young’s modulus of the material, was taken as the average slope of the steepest segment of the approach

force curve. On changing the temperature, the sample was allowed to equilibrate for 15 min before commencing imaging. To calibrate the tip for use at different temperatures (and therefore

allow meaningful comparison of force data), following equilibration at the desired temperature the tip was positioned 50 µm above the surface and automatically calibrated using the built-in

Sader method in the Nanowizard software, with the temperature set to that of the heating stage. HYDROLYTIC DEGRADATION STUDIES Accelerated degradation studies were conducted under conditions

previously reported by Lam et al76. All polymers (_n_ = 3 for each composition in each solution, 18 total samples) were prepared as “degradation disks” (_ca_. 0.1 g) using heated

compression moulding and subjected to aqueous environments of various pH (PBS, 1 M aq. NaOH, and 5 M aq. NaOH). The disks were placed in individual vials containing 20 mL of the

corresponding solution and incubated at 37 °C with constant agitation at 60 rpm. Before analysis, the surface of each disk was dried in order to remove excess water before the weight was

periodically measured using an analytical balance. IN VITRO CELL STUDIES Polyamides were moulded into thin discs (_ca_. 0.3-mm thickness) with flat surfaces using compression moulding at 170

°C between two glass slides. PLLA was spin-coated onto a glass slide from a chloroform solution. MC3T3-E1 cells (ATCC, CRL-2593) were seeded at a density of 4000 cells cm−2 on top of the

polymer discs and cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in _α_-MEM enriched with 10% FBS and 1% pen/strep. Viability was detected after 24 h, 72 h and 7 days of incubation using PrestoBlue

proliferation assay and following manufacturer instructions. Fluorescence (_λ_Ex. = 530 nm, _λ_Em. = 590 nm) was measured using a BioTek plate reader. Statistical analysis was performed

using an ordinary two-way ANOVA test. IN VIVO ANIMAL STUDIES Experiments were performed in accordance with the European Commission Directive 2010/63/EU (European Convention for the

Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes) and the United Kingdom Home Office (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986) with project approval from the

institutional animal welfare and ethical review body (AWERB). Anaesthesia was induced in adult male Sprague Dawley rats (_n_ = 6 for each time point, 200–300 g) with isoflurane (2–4%;

Piramal Healthcare) in pure oxygen (BOC). Animals were placed prone onto a thermo-coupled heating pad (TCAT 2−LV; Physitemp), and body temperature was maintained at 36.7 °C. Four incisions

of 2-3 cm were made: two bilaterally over the spino-trapezius in equal location, and two bilaterally over the medial aspect of the dorsal external obliques. The skin was separated from the

muscle with large forceps, and any excess fat was removed. The implants were tunnelled under the skin and placed in direct contact with the muscle, at sites distal to the incision. The order

of the implants was randomised but constrained so that each implant appeared in each location at least once, including the PLLA control disc. All rats were implanted with a control material

(PLLA). The wounds were sealed with a subcuticular figure of 8 purse string suture with a set-back buried knot using 3-0 polyglactin sutures (Ethicon—Vicryl Rapide™). The surgical procedure

was performed under the strictest of aseptic conditions with the aid of a non-sterile assistant. Post-surgical analgesia was administered, and rats were placed into clean cages with food

and water ad libitum. 6 animals were sacrificed at each of the selected time points (4 and 8 weeks). Histology Studies Samples for histology were collected post-mortem by cutting the area

around the polymer implant to obtain tissue samples of _ca_. 1.5 cm2 with the polymer disc in the middle. Samples (_n_ = 6) were then cut in the middle of the polymer disc to get a

cross-section of both polymer and tissue, then placed in a 4% PFA solution overnight at 4 °C for fixation. Fixed samples were then washed with increasing % of ethanol (70–100%) followed by

100% xylene before embedding in paraffin. Embedded samples were cut to 5–20-µm-thick slices, de-paraffined in histological grade xylenes, rehydrated, and stained with either hematoxylin and

eosin (H&E) or Masson’s Trichrome stain, following standard Sigma-Aldrich protocols. Brightfield microscopy was used to examine pathology of select samples (at 4 weeks and 8 weeks), with

inflammatory cell load, necrosis presence and capsule thickness analysed at discreet intervals around the sample perimeter. Inflammatory scoring was based on ISO 10993 standard scoring

(scale range of 0–4, 0 = none, 1 = rare, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe). REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary

linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY The authors declare that full experimental details and characterisation of materials are available in the Supplementary Information. All raw data

that support the findings in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. REFERENCES * Bunn, C. W. Molecular structure and rubber-like elasticity I. The crystal

structures of β gutta-percha, rubber and polychloroprene. _Proc. R. Soc. Lond., A_ 180, 40–66 (1942). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Bunn, C. W. Molecular structure and rubber-like

elasticity III. Molecular movements in rubber-like polymers. _Proc. R. Soc. Lond., A_ 180, 40–66 (1942). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Coenen, A. M. J., Bernaerts, K. V., Harings, J.

A. W., Jockenhoevel, S. & Ghazanfari, S. Elastic materials for tissue engineering applications: Natural, synthetic, and hybrid polymers. _Acta Biomater._ 79, 60–82 (2018). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Zhang, Z., Ortiz, O., Goyal, R. & Kohn, J. in _Principles of Tissue Engineering (Fourth Edition)_ (eds. Lanza, R., Langer, R. & Joseph, V.) 441–473

(Academic Press, 2014). * Ji, B. & Gao, H. Mechanical properties of nanostructure of biological materials. _J. Mech. Phys. Solids_ 52, 1963–1990 (2004). Article ADS MATH Google

Scholar * Fung, Y. C. in _Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues_ (ed. Fung, Y. C.) 196–260 (Springer, New York, 1981). * O’Brien, F. J. Biomaterials & scaffolds for

tissue engineering. _Mater. Today_ 14, 88–95 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Capperauld, I. Suture materials: a review. _Clin. Mater._ 4, 3–12 (1989). Article Google Scholar *

Naleway, S. E., Lear, W., Kruzic, J. J. & Maughan, C. B. Mechanical properties of suture materials in general and cutaneous surgery. _J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B_ 103, 735–742 (2015).

Article CAS Google Scholar * V. Risbud, M. & Bhonde, R. R. Polyamide 6 composite membranes: properties and in vitro biocompatibility evaluation. _J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed._ 12,

125–136 (2001). Article Google Scholar * Pruitt, L. & Furmanski, J. Polymeric biomaterials for load-bearing medical devices. _JOM_ 61, 14–20 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Winnacker, M. Polyamides and their functionalization: recent concepts for their applications as biomaterials. _Biomater. Sci._ 5, 1230–1235 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Abdal-hay, A., Pant, H. R. & Lim, J. K. Super-hydrophilic electrospun nylon-6/hydroxyapatite membrane for bone tissue engineering. _Eur. Polym. J._ 49, 1314–1321 (2013). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Abdal-hay, A., Hamdy, A. S. & Khalil, K. A. Fabrication of durable high performance hybrid nanofiber scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration using a novel, simple in

situ deposition approach of polyvinyl alcohol on electrospun nylon 6 nanofibers. _Mater. Lett._ 147, 25–28 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Abdal-hay, A., Salam Hamdy, A., Morsi, Y.,

Abdelrazek Khalil, K. & Hyun Lim, J. Novel bone regeneration matrix for next-generation biomaterial using a vertical array of carbonated hydroxyapatite nanoplates coated onto electrospun

nylon 6 nanofibers. _Mater. Lett._ 137, 378–381 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wei, J. & Li, Y. Tissue engineering scaffold material of nano-apatite crystals and polyamide

composite. _Eur. Polym. J._ 40, 509–515 (2004). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wang, H. et al. Biocompatibility and osteogenesis of biomimetic nano-hydroxyapatite/polyamide composite

scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. _Biomaterials_ 28, 3338–3348 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Khadka, A. et al. Evaluation of hybrid porous biomimetic

nano-hydroxyapatite/polyamide 6 and bone marrow-derived stem cell construct in repair of calvarial critical size defect. _J. Craniofacial Surg._ 22, 1852–1858 (2011). Article Google Scholar

* You, F. et al. Fabrication and osteogenesis of a porous nanohydroxyapatite/polyamide scaffold with an anisotropic architecture. _ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng._ 1, 825–833 (2015). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Pant, H. R. & Kim, C. S. Electrospun gelatin/nylon-6 composite nanofibers for biomedical applications. _Polym. Int._ 62, 1008–1013 (2013). CAS Google Scholar

* Shrestha, B. K. et al. Development of polyamide-6,6/chitosan electrospun hybrid nanofibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering application. _Carbohydr. Polym._ 148, 107–114 (2016). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Guo, K. & Chu, C. C. Controlled release of paclitaxel from biodegradable unsaturated poly(ester amide)s/poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogels. _J.

Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed._ 18, 489–504 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Guo, K., Chu, C. C., Chkhaidze, E. & Katsarava, R. Synthesis and characterization of novel biodegradable

unsaturated poly(ester amide)s. _J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem._ 43, 1463–1477 (2005). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Xiao, C. & He, Y. Tailor-made unsaturated

poly(ester-amide) network that contains monomeric lactate sequences. _Polym. Int._ 56, 816–819 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Cai, Z., Wan, Y., Becker, M. L., Long, Y.-Z. &

Dean, D. Poly(propylene fumarate)-based materials: synthesis, functionalization, properties, device fabrication and biomedical applications. _Biomaterials_ 208, 45–71 (2019). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Guvendiren, M., Molde, J., Soares, R. M. D. & Kohn, J. Designing biomaterials for 3D printing. _ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng._ 2, 1679–1693 (2016). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tatara, A. M. et al. Synthesis and characterization of diol-based unsaturated polyesters: Poly(diol fumarate) and poly(diol fumarate-co-succinate).

_Biomacromolecules_ 18, 1724–1735 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Walker, J. M. et al. Effect of chemical and physical properties on the in vitro degradation of 3D printed

high resolution poly(propylene fumarate) scaffolds. _Biomacromolecules_ 18, 1419–1425 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Childers, E. P., Wang, M. O., Becker, M. L., Fisher, J.

P. & Dean, D. 3D printing of resorbable poly(propylene fumarate) tissue engineering scaffolds. _MRS Bull._ 40, 119–126 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lee, K.-W. et al.

Poly(propylene fumarate) bone tissue engineering scaffold fabrication using stereolithography: effects of resin formulations and laser parameters. _Biomacromolecules_ 8, 1077–1084 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Timmer, M. D., Ambrose, C. G. & Mikos, A. G. In vitro degradation of polymeric networks of poly(propylene fumarate) and the crosslinking macromer

poly(propylene fumarate)-diacrylate. _Biomaterials_ 24, 571–577 (2003). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shin, H., Jo, S. & Mikos, A. G. Modulation of marrow stromal osteoblast

adhesion on biomimetic oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate] hydrogels modified with Arg-Gly-Asp peptides and a poly(ethylene glycol) spacer. _J. Biomed. Mater. Res._ 61, 169–179 (2002).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fisher, J. P., Dean, D. & Mikos, A. G. Photocrosslinking characteristics and mechanical properties of diethyl fumarate/poly(propylene fumarate)

biomaterials. _Biomaterials_ 23, 4333–4343 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lewandrowski, K.-U., Gresser, J. D., Wise, D. L., White, R. L. & Trantolo, D. J.

Osteoconductivity of an injectable and bioresorbable poly(propylene glycol-co-fumaric acid) bone cement. _Biomaterials_ 21, 293–298 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Curtis, L.

G., Edwards, D. L., Simons, R. M., Trent, P. J. & Von Bramer, P. T. Investigation of maleate-fumarate isomerization in unsaturated polyesters by nuclear magnetic resonance. _Ind. Eng.

Chem. Prod. Res. Dev._ 3, 218–221 (1964). Article CAS Google Scholar * Farmer, T. J., Macquarrie, D. J., Comerford, J. W., Pellis, A. & Clark, J. H. Insights into post-polymerisation

modification of bio-based unsaturated itaconate and fumarate polyesters via aza-Michael addition: understanding the effects of C=C isomerisation. _J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem._ 56,

1935–1945 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Yu, Y., Wei, Z., Leng, X. & Li, Y. Facile preparation of stereochemistry-controllable biobased poly(butylene maleate-co-butylene

fumarate) unsaturated copolyesters: a chemoselective polymer platform for versatile functionalization via aza-Michael addition. _Polym. Chem._ 9, 5426–5441 (2018). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Kricheldorf, H. R., Yashiro, T. & Weidner, S. Isomerization-free polycondensations of maleic anhydride with α,ω-alkanediols. _Macromolecules_ 42, 6433–6439 (2009). Article

ADS CAS Google Scholar * Yashiro, T., Kricheldorf, H. R. & Huijser, S. Polycondensations of substituted maleic anhydrides and 1,6-hexanediol catalyzed by metal triflates. _J.

Macromol. Sci. A_ 47, 202–208 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wróblewska, A. A., Stevens, S., Garsten, W., De Wildeman, S. M. A. & Bernaerts, K. V. Solvent-free method for the

copolymerization of labile sugar-derived building blocks into polyamides. _ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng._ 6, 13504–13517 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Wróblewska,

A. A., Bernaerts, K. V. & De Wildeman, S. M. A. Rigid, bio-based polyamides from galactaric acid derivatives with elevated glass transition temperatures and their characterization.

_Polymer_ 124, 252–262 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Galbis, J. A., García-Martín, Md. G., de Paz, M. V. & Galbis, E. Synthetic polymers from sugar-based monomers. _Chem. Rev._

116, 1600–1636 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wu, Y., Enomoto-Rogers, Y., Masaki, H. & Iwata, T. Synthesis of crystalline and amphiphilic polymers from D-glucaric acid.

_ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng._ 4, 3812–3819 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jasinska, L. et al. Novel, fully biobased semicrystalline polyamides. _Macromolecules_ 44, 3458–3466 (2011).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Fernández, C. E. et al. Crystallization studies on linear aliphatic polyamides derived from naturally occurring carbohydrates. _J. Appl. Polym. Sci._

116, 2515–2525 (2010). Google Scholar * Muñoz-Guerra, S. et al. Crystalline structure and crystallization of stereoisomeric polyamides derived from arabinaric acid. _Polymer_ 50, 2048–2057

(2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zamora, F. et al. Stereoregular copolyamides derived from D-xylose and L-arabinose. _Macromolecules_ 33, 2030–2038 (2000). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * García-Martín, Md. G. et al. Synthesis and characterization of linear polyamides derived from L-arabinitol and xylitol. _Macromolecules_ 37, 5550–5556 (2004). Article ADS CAS

Google Scholar * Oliva, R., Ortenzi, M. A., Salvini, A., Papacchini, A. & Giomi, D. One-pot oligoamides syntheses from L-lysine and L-tartaric acid. _RSC Adv._ 7, 12054–12062 (2017).

Article CAS ADS Google Scholar * Majó, M. A., Alla, A., Bou, J. J., Herranz, C. & Muñoz-Guerra, S. Synthesis and characterization of polyamides obtained from tartaric acid and

L-lysine. _Eur. Polym. J._ 40, 2699–2708 (2004). Article CAS Google Scholar * Alla, A., Oxelbark, J., Rodríguez-Galán, A. & Muñoz-Guerra, S. Acylated and hydroxylated polyamides

derived from L-tartaric acid. _Polymer_ 46, 2854–2861 (2005). Article CAS Google Scholar * Regaño, C. et al. Stereocopolyamides derived from 2,3-di-O-methyl-D- and -L-tartaric acids and

hexamethylenediamine. 1. Synthesis, characterization, and compared properties. _Macromolecules_ 29, 8404–8412 (1996). Article ADS Google Scholar * Bou, J. J., Rodriguez-Galan, A. &

Munoz-Guerra, S. Optically active polyamides derived from L-tartaric acid. _Macromolecules_ 26, 5664–5670 (1993). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Winnacker, M., Neumeier, M., Zhang, X.,

Papadakis, C. M. & Rieger, B. Sustainable chiral polyamides with high melting temperature via enhanced anionic polymerization of a menthone-derived lactam. _Macromol. Rapid Commun._ 37,

851–857 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Winnacker, M., Vagin, S., Auer, V. & Rieger, B. Synthesis of novel sustainable oligoamides via ring-opening polymerization of

lactams based on (−)-menthone. _Macromol. Chem. Phys._ 215, 1654–1660 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Firdaus, M. & Meier, M. A. R. Renewable polyamides and polyurethanes derived

from limonene. _Green. Chem._ 15, 370–380 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Huang, D., Liu, Y., Qin, A. & Tang, B. Z. Recent advances in alkyne-based click polymerizations.

_Polym. Chem._ 9, 2853–2867 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lowe, A. B. Thiol-yne ‘click’/coupling chemistry and recent applications in polymer and materials synthesis and

modification. _Polymer_ 55, 5517–5549 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * He, B. et al. Spontaneous amino-yne click polymerization: a powerful tool toward regio- and stereospecific

poly(β-aminoacrylate)s. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 139, 5437–5443 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bell, C. A. et al. Independent control of elastomer properties through

stereocontrolled synthesis. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 55, 13076–13080 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Deng, H. et al. Construction of regio- and stereoregular poly(enaminone)s by

multicomponent tandem polymerizations of diynes, diaroyl chloride and primary amines. _Polym. Chem._ 6, 4436–4446 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Deng, H., He, Z., Lam, J. W. Y.

& Tang, B. Z. Regio- and stereoselective construction of stimuli-responsive macromolecules by a sequential coupling-hydroamination polymerization route. _Polym. Chem._ 6, 8297–8305

(2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Truong Vinh, X. & Dove Andrew, P. Organocatalytic, regioselective nucleophilic “click” addition of thiols to propiolic acid esters for

polymer–polymer coupling. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed._ 52, 4132–4136 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Liu, J. et al. Thiol−yne click polymerization: Regio- and stereoselective synthesis of

sulfur-rich acetylenic polymers with controllable chain conformations and tunable optical properties. _Macromolecules_ 44, 68–79 (2011). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Jim, C. K. W.

et al. Metal-free alkyne polyhydrothiolation: Synthesis of functional poly(vinylenesulfide)s with high stereoregularity by regioselective thioclick polymerization. _Adv. Funct. Mater._ 20,

1319–1328 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * El Feninat, F., Laroche, G., Fiset, M. & Mantovani, D. Shape memory materials for biomedical applications. _Adv. Eng. Mater._ 4, 91–104

(2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * Peterson, G. I., Dobrynin, A. V. & Becker, M. L. Biodegradable shape memory polymers in medicine. _Adv. Healthc. Mater._ 6, 1700694 (2017).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Chan, B. Q. Y. et al. Recent advances in shape memory soft materials for biomedical applications. _ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces_ 8, 10070–10087 (2016). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Li, M., Guan, Q. & Dingemans, T. J. Hwsigh-temperature shape memory behavior of semicrystalline polyamide thermosets. _ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces_ 10,

19106–19115 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Elgendy, H. M., Norman, M. E., Keaton, A. R. & Laurencin, C. T. Osteoblast-like cell (MC3T3-E1) proliferation

on bioerodible polymers: an approach towards the development of a bone-bioerodible polymer composite material. _Biomaterials_ 14, 263–269 (1993). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wu,

X. & Wang, S. Regulating MC3T3-E1 cells on deformable poly(ε-caprolactone) honeycomb films prepared using a surfactant-free breath figure method in a water-miscible solvent. _ACS Appl.

Mater. Interfaces_ 4, 4966–4975 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Akbarzadeh, R. et al. Hierarchical polymeric scaffolds support the growth of MC3T3-E1 cells. _J. Mater. Sci.:

Mater. Med._ 26, 116 (2015). Google Scholar * Higgins, D. M. et al. Localized immunosuppressive environment in the foreign body response to implanted biomaterials. _Am. J. Pathol._ 175,

161–170 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gehrke, A. S. et al. New implant macrogeometry to improve and accelerate the osseointegration: an in vivo experimental

study. _Appl. Sci._ 9, 3181 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yanagisawa, Y., Nan, Y. L., Okuro, K. & Aida, T. Mechanically robust, readily repairable polymers via tailored

noncovalent cross-linking. _Science_ 359, 72–76 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lam, C. X. F., Savalani, M. M., Teoh, S.-H. & Hutmacher, D. W. Dynamics of in vitro

polymer degradation of polycaprolactone-based scaffolds: accelerated versus simulated physiological conditions. _Biomed. Mater._ 3, 034108 (2008). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS J.C.W. and A.C.W. acknowledge funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant

agreement Nos. 751150 and 793247 respectively. M.L.B. acknowledges the W. Gerald Austen Endowed Chair in Polymer Science and Polymer Engineering for funding these efforts. A.P.D. thanks the

European Research Council (grant number 681559) for funding. All three external reviewers are thanked for their time and contribution to the final version of this publication. AUTHOR

INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * School of Chemistry, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK Joshua C. Worch, Andrew C. Weems, Maria C. Arno, Thomas R. Wilks,

Rachel K. O’Reilly & Andrew P. Dove * Department of Polymer Science, The University of Akron, Akron, OH, 44325, USA Jiayi Yu * School of Life Sciences, University of Warwick, Coventry,

CV4 7AL, UK Robert T. R. Huckstepp * Department of Chemistry, Department of Mechanical Engineering & Materials Science, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Duke University, 308 Research

Drive, Durham, NC, 27708, USA Matthew L. Becker Authors * Joshua C. Worch View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Andrew C. Weems View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jiayi Yu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Maria C. Arno View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Thomas R. Wilks View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Robert T. R. Huckstepp View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Rachel K. O’Reilly View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Matthew L. Becker View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Andrew P. Dove View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS J.C.W., A.P.D. and M.L.B. conceived the material synthesis and designed the project idea. J.C.W. synthesised and characterised the

materials. J.C.W., J.Y. and A.C.W. performed thermal and mechanical analyses. T.R.W. conducted AFM analysis under the supervision of R.K.O’R. M.C.A. and A.P.D. designed the in vitro and,

with R.T.R.H., in vivo experiments. M.C.A. performed in vitro analyses, M.C.A. and R.T.R.H. performed in vivo experiments while A.C.W. performed the histology. The paper was written through

contributions of J.C.W., A.C.W., M.L.B. and A.P.D. All authors have given approval to the final version of the paper. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Matthew L. Becker or Andrew P.

Dove. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks Malte Winnacker and

the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN

ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format,

as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third

party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright

holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Worch, J.C., Weems, A.C., Yu, J. _et

al._ Elastomeric polyamide biomaterials with stereochemically tuneable mechanical properties and shape memory. _Nat Commun_ 11, 3250 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16945-8

Download citation * Received: 29 June 2019 * Accepted: 27 May 2020 * Published: 26 June 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16945-8 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative