- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Despite intensive study, plant lysine catabolism beyond the 2-oxoadipate (2OA) intermediate remains unvalidated. Recently we described a missing step in the D-lysine catabolism of

_Pseudomonas putida_ in which 2OA is converted to D-2-hydroxyglutarate (2HG) via hydroxyglutarate synthase (HglS), a DUF1338 family protein. Here we solve the structure of HglS to 1.1 Å

resolution in substrate-free form and in complex with 2OA. We propose a successive decarboxylation and intramolecular hydroxylation mechanism forming 2HG in a Fe(II)- and O2-dependent

manner. Specificity is mediated by a single arginine, highly conserved across most DUF1338 proteins. An _Arabidopsis thaliana_ HglS homolog coexpresses with known lysine catabolism enzymes,

and mutants show phenotypes consistent with disrupted lysine catabolism. Structural and biochemical analysis of _Oryza sativa_ homolog FLO7 reveals identical activity to HglS despite low

sequence identity. Our results suggest DUF1338-containing enzymes catalyze the same biochemical reaction, exerting the same physiological function across bacteria and eukaryotes. SIMILAR

CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS IRON-SULFUR CLUSTERS ARE INVOLVED IN POST-TRANSLATIONAL ARGINYLATION Article Open access 28 January 2023 _OSTH1_ IS A KEY PLAYER IN THIAMIN BIOSYNTHESIS IN

RICE Article Open access 12 June 2024 Α-PROTEOBACTERIA SYNTHESIZE BIOTIN PRECURSOR PIMELOYL-ACP USING BIOZ 3-KETOACYL-ACP SYNTHASE AND LYSINE CATABOLISM Article Open access 05 November 2020

INTRODUCTION Lysine is an essential amino acid, and due to its low abundance in cereals and legumes it is produced on a scale of one million tons a year to supplement food supply needs1,2,3.

To thwart malnutrition in the developing world, significant work has been done to engineer rice, maize and other plants to produce greater quantities of lysine3,4. Increasing lysine levels

in cereal grains requires overexpression of lysine-producing enzymes and concurrent disruption of lysine catabolism3. Thus, mutants such as _opaque2_ in maize have received considerable

attention for their ability to accumulate lysine within their endosperm5,6. However, despite worldwide importance, the full plant lysine catabolism pathway remains unknown, with no consensus

in the steps beyond 2-oxoadipate (2OA) formation7. Recently we described a novel D-lysine catabolic route in the bacterium _Pseudomonas putida_ which also contains a 2OA intermediate,

similar to plant L-lysine catabolism8. In the _P. putida_ pathway, 2OA is converted to 2-oxoglutarate (2OG) via three enzymes, one of which catalyzes a unique decarboxylation–hydroxylation

step. In this step, 2OA is converted to D-2-hydroxyglutarate (2HG) in a reaction catalyzed by the Fe(II)-dependent DUF1338 family enzyme hydroxyglutarate synthase (HglS) (Supplementary Fig.

1)8. Homologs of this enzyme are broadly distributed across multiple domains of life, including nearly every sequenced plant genome8,9. However, only one study describing DUF1338 enzymes in

plants has been reported. In _Oryza sativa FLO7_ (a DUF1338 family member) mutants, abnormal starch formation was observed in the endosperm similar to maize _opaque2_ mutants that are known

to accumulate high levels of lysine9. The widespread DUF1338 family abundance in plants and the _FLO7_ and _opaque2_ phenotypes encouraged us to further investigate whether enzymes

throughout the family displayed similar activity to HglS. Conversion of 2OA directly to D-2HG requires two discrete chemical steps, a decarboxylation and hydroxylation, making the chemical

mechanism of the enzyme puzzling8. Here, we leverage structural and biochemical analyses to postulate a chemical mechanism for HglS and characterize its substrate specificity. We show that

critical residues involved in catalysis are highly conserved across nearly all DUF1338 family proteins. We further show that despite very low sequence identity, plant homologs also catalyze

the conversion of 2OA to 2HG and adopt the same structural fold as the bacterial enzyme, suggesting that DUF1338 family proteins catalyze the last unknown step of plant lysine catabolism.

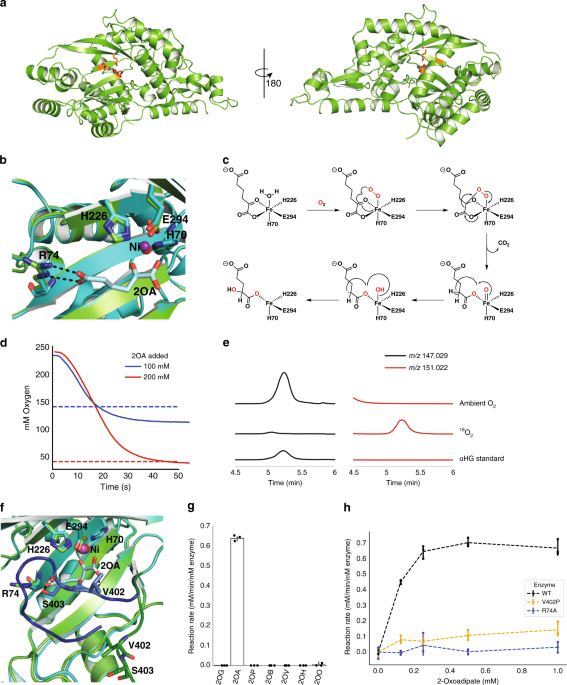

RESULTS STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS REVEALS THE CATALYTIC MECHANISM OF HGLS To better understand the unusual HglS reaction, we obtained crystal structures of the enzyme both with and without a bound

substrate. Initially, Hg1S was crystallized without substrate, and the Hg1S structure was solved at 1.1 Å resolution (Fig. 1a). The enzyme possesses a central β-sheet motif resembling a

partially-closed β-barrel consisting of seven β-sheets, which is conserved in the three other DUF1338 structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB IDs 3LHO, 3IUZ, and 2RJB). Further

analysis also revealed the presence of a metal cofactor bound within a conserved metal cofactor-binding motif—consisting of the residues His 70, His 226, and Glu 294—common to the DUF1338

structures. However, none of the available DUF1338 structures have been biochemically characterized or solved in complex with a substrate, and consequently no chemical reaction mechanism for

the family has been proposed. Therefore, we performed a search for characterized proteins with similar structures using the Vector Alignment Search Tool (VAST)10. The top VAST hits were the

three reported DUF1338 structures, followed by the hydroxymandelate synthase (HMS) and 4-hydroxyphenyl pyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD) structures (Supplementary Data 1)11,12. HglS and HMS

structure comparison revealed the two enzymes share a similar central β-sheet fold common to the DUF1338 structures (Supplementary Fig. 2)11,13. More importantly, the β-sheet domain of HMS

contains the enzyme active site, two histidines and a glutamate that bind the metal cofactor in nearly the same orientation as in HglS. The similarity of the HglS, HMS, and HPPD folds and

active sites suggested that HglS is likely an additional member of the vicinal oxygen chelate (VOC) enzyme superfamily and could act via a similar mechanism to HMS and HPPD14,15. To

determine metal cofactor identity within the HglS structure, we conducted a fluorescent scan of a HglS crystal. We detected a photon emission near 7475 eV, the K-alpha emission of nickel

(Supplementary Fig. 3). In addition, a less intense peak corresponding to the K-alpha emission of iron was also observed. We therefore assigned the co-crystallized metal as Ni(II) with a

small percent Fe(II) occupancy. While the metal cofactors present in the HMS and HglS structures differ, we previously determined that HglS utilizes Fe(II), not Ni(II), for catalysis. The

nickel bound to HglS is likely derived from the nickel affinity chromatography protein purification. The HglS domain architecture suggests the enzyme belongs to the VOC superfamily,

mandating a chemical mechanism employing the bidentate coordination of vicinal oxygen atoms to a divalent metal center. Given the established HMS substrate-binding mode, we hypothesized that

the metal in HglS would bind the vicinal oxygen atoms of the α-keto group of 2OA11. We therefore soaked HglS crystals with 2OA and solved the structure of the resulting complex. The

noncatalytic active site nickel prevented enzyme turnover, yielding a substrate-bound structure, and no observed product density. As hypothesized, the substrate carboxylate and α-keto group

oxygens are coordinated to the metal (Fig. 1b), classifying HglS as a VOC superfamily member. We had previously noted the similarity between the set of reactions catalyzed by HglS and

HMS8,11,13. Both enzymes perform a decarboxylation–hydroxylation reaction on a α-ketoacid substrate. HPPD catalyzes a similar overall reaction with the hydroxylation occurring at a different

position. The structural and biochemical similarity of HglS to HMS and HPPD led us to propose a similar chemical mechanism for HglS (Fig. 1c). More specifically, the catalytic cycle begins

when the substrate carboxylate and α-keto group oxygens and molecular oxygen bind to the three open Fe(II) coordination sites. A radical rearrangement results in a decarboxylation and the

formation of a Fe(IV)-oxo and an α-radical species. Finally, continued radical rearrangement produces the hydroxylated product 2-hydroxyglutarate. If HglS follows this mechanism, it should

consume 1 mol of O2 per mole of 2OA, and two oxygens in the product should derive from molecular O2. To support this mechanism, we determined the stoichiometry of 2OA to O2 consumption using

a dissolved oxygen probe. In the presence of 100 or 200 µM 2OA, the enzyme consumed approximately an equimolar concentration of O2 (Fig. 1d). No feedback inhibition was observed with 1 mM

D-2HG, or L-2HG (Supplementary Fig. 4a), and kinetic parameters determined by monitoring oxygen consumption were similar to those we previously reported using a different enzyme assay

(Supplementary Fig. 4b)8. We next tested our hypothesis that two oxygen atoms in the 2HG product derive from molecular O2. To determine the source of oxygen atoms, additional enzyme assays

were performed under an 18O2 atmosphere. High resolution LC-MS product analysis revealed a species exhibiting a _m_/_z_ of 151.022 that co-eluted with a 2HG standard (_m_/_z_ 147.029),

corresponding to the expected _m_/_z_ of 2HG containing two 18O-labeled oxygens (Fig. 1e). These results strongly suggest HglS proceeds via a mechanism similar to HMS and is therefore the

third identified member of the two-substrate α-ketoacid-dependent oxygenase (2S-αKAO) family14. Further analysis of the co-crystal structure revealed several other substrate-binding

residues. Specifically, arginine 74 forms a salt bridge with the distal carboxylate of the 2OA substrate. In addition, valine 402 and serine 403 form hydrogen bonds with the carboxylate keto

group and distal carboxylate group, respectively (Fig. 1f). The loop containing residues 402 and 403 shifts approximately 10 Å from the _holo_ state to the enzyme-bound state, bringing it

into proximity with the substrate. We investigated the importance of Arg74 in determining enzyme specificity by assaying enzyme activity against a panel of α-ketoacids (Fig. 1g). HglS

exhibited activity only with 2OA, and displayed no detectable and statistically significant activity above background (a boiled enzyme control) on any other substrate. We therefore concluded

that Arg74 participates in favorable substrate-binding interactions, but it also appears to influence the strict enzyme substrate specificity. Furthermore, an R74A mutation abolished

enzymatic activity (Fig. 1h). We additionally probed the importance of the loop bearing Val402 and Ser403 on substrate binding. Mutating Val402 to a proline residue to disrupt the hydrogen

bond observed between 2OA and the amide backbone of Val402 significantly decreased enzyme activity, suggesting that while this residue is not essential for turnover, it likely contributes to

substrate-binding affinity (Fig. 1h). However, it is also possible that the observed decrease in activity is an artefact of disrupted protein folding due to the introduction of a proline

residue. Further experiments with more conservative mutations at positions 402 and 403 will be required to fully understand the role(s) of these residues in substrate binding and/or

catalysis. DUF1338 BIOCHEMISTRY AND STRUCTURE IS CONSERVED IN HOMOLOGS Based on the mechanistic information gleaned from our HglS biochemical and structural characterization, we sought to

propose potential functions for other DUF1338 family members. Previously, we showed that DUF1338 family proteins are widely distributed across several domains of life, while others have

demonstrated that DUF1338 protein coding sequences are present in the majority of sequenced plant genomes8,9. In plants, the catabolism of lysine is known only until 2OA, with further

catabolic steps having only been hypothesized7. Furthermore, D-2HG has also been identified as an intermediate in plant lysine catabolism, though the mechanism of its formation has yet to be

proven. We therefore hypothesized that plant homologs perform the same reaction as HglS, converting 2OA to 2HG. To test this, we biochemically characterized the DUF1338 homologs from

_Arabidopsis thaliana_ and _O. sativa_ as well as an additional distantly related _Escherichia coli_ homolog. Soluble variants of plant proteins were constructed by removing the predicted

N-terminal localization peptide. As expected, the _E. coli_ homolog YdcJ and the plant homologs AT1G07040 and FLO7 catalyzed the conversion of 2OA to that was confirmed by in vitro assays

analyzed using high resolution LC-MS (Supplementary Fig. 5a). In addition, the FLO7 homolog displayed kinetic parameters similar to HglS, with a _K_m of 0.55 mM and a _V_max of 0.89

mM/min/µM enzyme (Supplementary Fig. 5b). In addition, the structural conservation between bacterial and eukaryotic DUF1338 proteins was compared by obtaining a crystal structure of FLO7.

Initial crystallization screens resulted in crystals that were soaked with 2OA, producing diffraction data used to solve the substrate-bound crystal structure at 1.85 Å resolution. The FLO7

crystal structure, like the other DUF1338 proteins, displayed the conserved central VOC fold containing the active site and metal-binding center (Fig. 2a). Comparison of the HglS and FLO7

structures revealed that orientation of the metal-coordinating residues and 2OA in both structures were nearly identical (Fig. 2b) even though the proteins display low (~15%) sequence

identity (Supplementary Fig. 6). In addition, the FLO7 structure also contains a substrate-binding arginine, Arg64, located in nearly the same position as Arg74 of HglS. However, unlike

Val402 and Ser403 of HglS, FLO7 does not possess any other residues interacting with the substrate. The results of our biochemical and structural studies of FLO7 manifest the remarkable

conservation of the fold, active site architecture, and mechanism among DUF1338 proteins across different domains of life. Consequently, we predict that all DUF1338 proteins containing the

conserved 2OA-interacting arginine likely catalyze the decarboxylation and hydroxylation of 2OA to form 2HG. These hydroxyglutarate synthases form a new two-substrate α-ketoacid-dependent

oxygenase (2S-αKAO) subfamily lacking significant sequence identity to HMS or 4-HPPD and acting on a distinct substrate. CONSERVED RESIDUES SUGGEST A COMMON BIOCHEMICAL ROLE The conserved

structural features, substrate, and biochemical activity of plant and bacterial DUF1338 proteins suggest a common physiological role across domains of life. Therefore we analyzed all known

DUF1338 domain-containing protein amino acid sequences for the key catalytic and substrate-binding residues we identified in HglS. First, we queried all DUF1338 proteins within the Pfam

database for the catalytic and metal-binding residues identified in HglS. Of the 2417 unique DUF1338-containing proteins found in the Pfam PF07063 family, 86% possess the conserved “HHE”

metal-binding triad (Supplementary Table 1). This strong conservation is consistent across domains of life, with 85% of DUF1338 proteins in bacteria, 92% in fungi, and 81% in plants

possessing the metal-binding residues. Further analysis revealed arginine 74, which dictates HglS substrate specificity, is also highly conserved across the family. Of the homologs with

conserved HHE triads, 100% of fungal proteins, 99.7% of bacterial proteins, and 93.4% of plant proteins maintain an arginine at this position (Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, though there

is little primary sequence identity between bacterial homologs and plant homologs (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7), the critical residues coordinating the Fe(II) cofactor and the

carboxylate-coordinating arginine are highly conserved. Given the substrate specificity exhibited by the _P. putida_ DUF1338 protein HglS, we hypothesized that the remaining uncharacterized

homologs maintaining the metal-binding residues and conserved arginine would also use 2OA as a substrate. Nearly all plant and algal genomes within GenBank encode DUF1338 family proteins

(Supplementary Table 1). Previous work to understand plant lysine catabolism suggested the missing reactions between 2OA and 2HG proceed through the 2-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex

(2KGD), forming glutaryl-Coenzyme A (Supplementary Fig. 8)7. Transcript correlation analysis in _A. thaliana_, however, revealed that the transcription of known lysine catabolic enzymes was

not correlated with 2KGD expression; rather, their transcription is highly correlated with a DUF1338 protein AT1G07040 (Supplementary Table 2). In addition, in _O. sativa_, mutants of the

DUF1338 protein FLO7 display a floury starch phenotype that resembles the maize _opaque2_ phenotype which is known to cause lysine accumulation in mutant kernels3,5,6,9. These transcriptomic

and phenotypic correlations suggest that, like HglS in _P. putida_, DUF1338 proteins are involved in the plant lysine degradation pathway. During seed maturation, lysine catabolism is

required for normal amyloplast development16. In rice, _FLO7_ localizes to the amyloplast via a N-terminal chloroplast localization signal peptide9. While the _A. thaliana_ homolog AT1G07040

also has a predicted chloroplast localization sequence, only 117 of 202 plant proteins had predicted chloroplast or mitochondria localization tags (Supplementary Table 3). Many predicted

non-localized proteins are isoforms of loci that also have putatively localized isoforms, though phylogenetic analysis also revealed a distinct non-localized DUF1338 protein clade

predominantly within _Brassicaceae_ (Supplementary Fig. 9). Notably, this non-localized subclade was enriched for proteins maintaining the HHE coordination triad but that possessed either a

glutamine or methionine at the position corresponding to Arg74 of HglS (Supplementary Fig. 9). As most plant homologs contain a localization tag, we predicted these homologs would likely

function similar to rice _FLO7_. We therefore tested whether mutants of the DUF1338 protein AT1G07040 from the model plant _A. thaliana_ exhibited a phenotype resembling other plant

lysine-accumulating mutants. When grown on germination media, Salk_103299C mutants (which have confirmed homozygous T-DNA insertions in the AT1G07040 locus) displayed significantly delayed

germination compared with wild-type seedlings (Supplementary Fig. 10a). AT1G07040 mutants that germinated also displayed compromised development and appeared cholortic with impaired growth

(Supplementary Fig. 10a). This phenotype was recapitulated when seeds were germinated in soil. After a 14 day incubation, no Salk_103299C seeds germinated whereas 95% of wild-type seeds had

germinated (_n_ = 96) (Supplementary Fig. 10c). After 45 days, only 7% of mutant seeds had germinated and after 60 days, only 15%. This phenotype is consistent with previous work showing

lysine accumulation in _A. thaliana_ seeds resulted in significantly delayed germination16,17. Toluidine blue staining of sectioned mutant seeds also suggested that oil body formation was

altered (Supplementary Fig. 10b). The altered morphology of the oil body, serving as the primary carbon storage unit in _A. thaliana_, is analogous to the altered starch granule formation

observed in rice _FLO7_ mutants9. The aberrant phenotype in both _A. thaliana_ and rice mutants suggest that DUF1338 homologs play a critical role in embryo development both in monocots and

dicots. The phenotypes in _A. thaliana_ observed in this preliminary work will need to be validated using multiple confirmed T-DNA lines that disrupt the function of AT1G07040. DISCUSSION

Here, we present the structural and mechanistic analysis of HglS, the first DUF1338 protein family member to be assigned a function. In a previous report, we showed that HglS converts 2OA to

2HG. The HglS chemical mechanism remained ambiguous however, as this conversion involves two apparent enzymatic steps: decarboxylation and hydroxylation. Here we report the high resolution

crystal structures of _holo_- and substrate-bound enzyme aiding the proposal of an enzyme mechanism. In addition, we present the substrate-bound structure of the plant homolog, FLO7. Several

HglS unique features were used to propose an enzymatic reaction mechanism. A VAST structural similarity search revealed the central VOC superfamily β-sheet fold, and metal-binding residues

of HglS were positioned similarly to the corresponding HMS and HPPD residues (Supplementary Data 1). Both HMS and HPPD catalyze an intramolecular decarboxylation–hydroxylation reaction but

share little sequence identity with HglS10. Furthermore, a 2OA-bound HglS co-crystal structure revealed bidentate coordination of the 2OA α-keto group by the metal center as a key step in

the enzymatic mechanism. These features were remarkably conserved in the FLO7 co-crystal structure, while the α-helices surrounding the central domain diverge. The VOC fold is conserved

across the protein superfamily, yet the specific orientation of β-sheets in HglS, FLO7, HMS, and HPPD appears to be most conserved in the intramolecular 2S-αKAO subfamily. With only seven

β-sheets composing the central barrel-like domain, the HglS structure diverges slightly from the canonical VOC fold which contains eight β-sheets. The central VOC domains of HglS, FLO7, HMS,

and HPPD are distinct from that of the mechanistically similar α-ketoglutarate (αKG) dependent dioxygenases which possess a double-stranded β-helix (jelly roll) fold containing the

metal-binding center and active site18. However, the orientation of metal-binding residues and bound substrate is understandably homologous given the similar chemical mechanisms of the

enzyme families, which we verified through several biochemical experiments. Whether the shared general mechanism of the 2S-αKAOs and αKG-dependent dioxygenases is a product of convergent

evolution remains unclear. While HMS and HPPD show significant sequence identity and share the same substrate, the DUF1338 family proteins are not homologous to HMS or HPPD, nor do they

share significant sequence identity with each other (~15% identity between HglS and FLO7). Low sequence conservation is a general VOC superfamily feature, but the low sequence identity

between members catalyzing the same reaction is less common14. Despite low primary sequence conservation, the biochemical assays of mutants, structural analysis, and bioinformatics reported

herein show that very few residues are essential for enzyme turnover in the hydroxyglutarate synthase family. It is possible that the α-helices surrounding the central VOC domain have been

selected for other attributes, such as mediating protein–protein interactions as observed in the αKG-dependent dioxygenases18. Previous work has shown DUF1338 family proteins are widespread

in bacteria and fungi, but they are especially prevalent in plants8,9. Our work here shows that the arginine residue that mediates the 2OA specificity of HglS is highly conserved across

these homologs. It is therefore likely that all DUF1338 proteins with the conserved arginine catalyze the decarboxylation and hydroxylation of 2OA to form 2HG. The enzyme’s substrate, 2OA,

is primarily known as a lysine catabolism intermediate, suggesting that DUF1338 enzymes participate in similar biochemical processes across domains of life

(http://modelseed.org/biochem/compounds/cpd00269). Previous plant phenotypic studies support this hypothesis; a rice study showed DUF1338-containing protein _FLO7_ disruption produced a

crystalline starch phenotype within the amyloplast9, similar to the lysine-accumulating _opaque2_ maize mutants19. DUF1338 protein AT1G07040 expression in _A. thaliana_ is highly correlated

with other known lysine catabolism enzymes. In this work, we further support this claim by showing that when AT1G07040 is disrupted, _A. thaliana_ seedlings have significantly compromised

germination ability. Previous work showed _A. thaliana_ lysine-accumulating mutants have delayed germination rates due to unfavorable TCA cycle effects, suggesting that AT1G07040 could be

involved in lysine degradation16,17. Furthermore, by assaying the _A. thaliana_ and rice enzymes in vitro, we show that AT1G07040 and FLO7 catalyze the transformation of 2OA to 2HG. While

both compounds were previously identified as plant lysine catabolism intermediates, no clear link between the two molecules had been demonstrated20. Finally, histopathological examination of

mutant AT1G07040 seeds showed aberrant oil body formation. While previous experiments showed that the disruption of lysine utilization compromises the ability of seeds to store carbon in

monocots such as rice and maize, our results show this phenomenon also occurs in dicots such as _Arabidopsis_. Given their near ubiquitous conservation and highly specific biochemical

function we find it likely that DUF1338 proteins localized to chloroplasts catalyze the last missing step in lysine catabolism of all green plants. While the majority of plant HglS homologs

have chloroplast localization tags, some lack any predicted signal peptide. This is especially prevalent in the _Brassicaceae_, where many species appear to have non-localized HglS paralogs.

The majority of these paralogs retain arginine as their specificity residue, but they may have roles in pathways beyond lysine catabolism as the _A. thaliana_ paralog AT1G27030 (lacking a

localization sequence) shows no expression correlation with known lysine catabolic genes (Supplementary Table 2). Recent studies show that the lysine-derived intermediates pipecolate and

N-hydroxy-pipecolate can initiate systemic acquired resistance (SAR) in plants21,22. SAR, a global response, grants lasting broad-spectrum disease protection in uninfected tissue23. In

bacteria, pipecolate is often catabolized to 2OA, suggesting that HglS homologs should receive future attention when studying pipecolate metabolism in plants. In addition to the

non-localized paralogs retaining the conserved arginine, multiple _Brassicaceae_ paralogs have altered residues at this position, harboring either methionine or asparagine. These paralogs

likely catalyze the decarboxylation and hydroxylation of substrates other than 2OA. Further research discerning the physiological and biochemical functionality of “mutant” paralogs is

warranted. DUF1338 proteins are also widely distributed in both _Ascomycota_ and _Basidiomycota_ fungi, though the model fungi _Saccharomyces cerevisiae_ or _Neurospora crassa_ lack

homologs. Within the fungal homologs examined here, all proteins containing a HHE metal-binding triad also maintained the arginine specificity residue suggesting that all function on a 2OA

substrate. Unfortunately, almost no fungal catabolic lysine pathways are fully characterized genetically or biochemically24. Multiple studies, however, suggested 2OA is a likely lysine

catabolism intermediate in _Pyriculuria oryzae_ and _Candida albicans_25,26. Moreover, while _P_. _oryzae_ possesses a DUF1338 homolog, _C. albicans_ does not. This implies _C. albicans_ and

other fungi may utilize a catabolic route similar to mammals in which 2OA is converted to glutaryl-CoA via 2OA dehydrogenase27. Future studies are required to examine whether fungal HglS

homologs also play a role in fungal lysine catabolism. Of the over 2000 bacterial HglS homologs examined here that retain the HHE triad, over 99% maintained arginine as the

specificity-conferring residue, suggesting widespread DUF1338 enzymatic activity conservation in prokaryotes. Previous work in _P. putida_ and published fitness data in _Pseudomonas

fluorescens_ and _Sinorhizobium meliloti_ provide evidence of a conserved physiological function as well8,28,29. _E. coli_ was recently shown to possess a non-ketogenic lysine catabolic

route via a glutarate hydroxylase, supplementing degradation routes to cadaverine30,31. _E. coli_ also possesses a HglS homolog, YdcJ, which we showed has identical activity to HglS. In

addition, the _E. coli_ enzyme structure was solved (PDB ID 2RJB) and shows the same conserved VOC fold, metal-binding motif, and arginine-binding residues as the HglS and FLO7 structures

reported herein. Future work will elucidate whether, like _P. putida_, _E. coli_ possesses multiple lysine catabolism routes or whether 2OA functions in other physiological processes. Low

cereal and legume lysine content produces protein-energy malnutrition in 30% of the developing world population3,32,33,34,35. Increasing lysine content in staple crops will require both

lysine overproduction and catabolic pathway elimination34. However, lysine metabolism changes in maize, rice, and soybeans resulted in low germination rates, abnormal endosperm, and reduced

grain weights3,19,36,37,38. We hope that the more complete understanding of lysine catabolism elucidated here will help resolve causes of pleiotropic effect in plants and aid in the

development of stable high-lysine crops to combat malnutrition globally. METHODS MEDIA, CHEMICALS, AND STRAINS Routine bacterial cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) Miller medium (BD

Biosciences, USA). _E. coli_ was grown at 37 °C. Cultures were supplemented with carbenicillin (100 mg/L, Sigma Aldrich, USA). All compounds with the exception of 2-oxohexanoic acid were

purchased through Sigma Aldrich. All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Supplementary Table 4 and are available through the public instance of the JBEI registry.

(https://public-registry.jbei.org/). _A. thaliana_ mutants were obtained from the Salk collection. DNA MANIPULATION All plasmids were designed using Device Editor and Vector Editor software,

while all primers used for the construction of plasmids were designed using j5 software39,40,41. All primers used in this study can be found in Supplementary Table 5. Plasmids were

assembled via Gibson Assembly using standard protocols42, or Golden Gate Assembly using standard protocols43. Plasmids were routinely isolated using the Qiaprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen,

USA), and all primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA). Site directed mutants were created by incorporating desired mutations into PCR primers. PCR

fragments were then re-assembled into the mutant plasmid using Golden Gate assembly44. The geneblock for the _E. coli_ codon optimized _O. sativa_ was purchased through IDT (Coralville, IA).

Arabidopsis cDNA was used to amplify AT1G07040. PROTEIN PURIFICATION A 5 mL overnight culture of _E. coli_ BL21 (DE3) containing the expression plasmid was used to inoculate a 500 mL

culture of LB. Cells were grown at 37 °C to an OD of 0.6 then induced with Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 1 mM. The temperature was lowered to 30 °C and

cells were allowed to express for 18 h before being harvested via centrifugation. Cell pellets were stored at −80 °C until purification. For purification, cell pellets were resuspended in

lysis buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM imidazole, 8% glycerol, pH 7.5) and sonicated to lyse cells. Insolubles were pelleted via centrifugation (30 min at 40,000

× _g_). The supernatant was applied to a fritted column containing Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen, USA), which had been pre-equilibrated with several column volumes of lysis buffer. The resin was

washed with lysis buffer containing 50 mM imidazole, then the protein was eluted using a stepwise gradient of lysis buffer containing increasing imidazole concentrations (100, 200, and 400

mM). Fractions were collected and analyzed via SDS-PAGE. Purified protein was dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 5% glycerol. CRYSTALLIZATION An initial crystallization

screen was set up using a Phoenix robot (Art Robbins Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA) using the sparse matrix screening method45. Purified HglS was concentrated to 20 mg/mL and Flo7 was

concentrated to 10 mg/mL prior to crystallization using the sitting drop method in 0.4 µL drops containing a 1:1 ratio of protein sample to crystallization solution. For HglS, the

crystallization solution consisted of 0.2 M Ammonium Fluoride and 20% PEG 3,350, while the crystallization solution for Flo7 contained 0.01 M Magnesium chloride hexahydrate, 0.05 M MES

monohydrate pH 5.6 and 1.8 M Lithium sulfate monohydrate. Crystals were transferred to crystallization solution containing 20% glycerol prior to flash freezing in liquid nitrogen. X-RAY DATA

COLLECTION AND MODEL REFINEMENT X-ray diffraction data for HglS were collected at the Berkeley Center for Structural Biology on beamline 5.0.2 and 8.2.2 of the Advanced Light Source at

Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. Diffraction data for Flo7 were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource on beamline 12-2. The HglS and Flo7 structures were determined by

the molecular-replacement method with the program _PHASER_46 using uncharacterized protein YdcJ (SF1787) from _Shigella flexneri_ (PDB ID: 2RJB) and the putative hydrolase (YP_751971.1) from

_Shewanella frigidimarina_ (PDB ID: 3LHO) as the search models, respectively. Structure refinement was performed by _phenix.refine_ program47. Manual rebuilding using COOT48 and the

addition of water molecules allowed for construction of the final model. The R-work and R-free values for the final models of all structures are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Root-mean-square deviations from ideal geometries for bond lengths, angles, and dihedrals were calculated with Phenix49. The overall stereochemical quality of the final models was assessed

using the MolProbity program50. Structural analyses were performed in Coot48, PyMOL (https://pymol.org/2/)51, and UCSF Chimera52. All structural data has been submitted to the Protein

Database with the following PDB IDs: HglS: 6W1G, HglS-2OA: 6W1H, Flo7-2OA:6 W1K. ENZYME KINETICS AND O2 CONSUMPTION Enzyme coupled decarboxylation assays were carried out as previously

described53. Reaction mixtures contained 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM NADH, 4 mM phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP), 100 U/mL pig heart malate dehydrogenase (Roche), 2 U/mL microbial

PEP carboxylase (Sigma), and 10 mM 2OA. Reactions were initiated by the addition of purified HglS or boiled enzyme controls, and absorbance at 340 nm was measured via a SpectraMax M4 plate

reader (Molecular Devices, USA). Initial rate measurements were directly recorded monitoring the consumption of O2 using a Clarke-type electrode (Hansatech Oxygraph). Reaction mixtures

containing FeSO4 (10 µM) and 2-oxoadipic acid (10–200 µM) in 100 mM Tris pH 7.0 were allowed to equilibrate to room temperature determined by a stable O2 concentration reading of 240 µM.

Addition of purified _apo_ enzyme (100 nM) to the sealed reaction vial initiated the reaction. Initial rates were determined from the linear portion of consumption of O2 corresponding to up

to 10% consumption of the limiting reactant. No burst or lag phases were observed. All assays were performed in triplicate. O2 consumption measurements used to determine the reaction

stoichiometry were also measured using a Clarke-type electrode. Reactions mixtures containing FeSO4 (10 µM) and 2-oxoadipic acid (100 or 200 µM) in 100 mM Tris pH 7.0 were equilibrate to

room temperature ([O2] = 240 µM) and monitored for at least 2 min prior to the addition of _apo_ enzyme (1 µM). Oxygen consumption was monitored until the signal plateaued and the O2

concentration was stable. The observed rate was determined by fitting the data to a single exponential decay model. The reaction stoichiometry was determined by taking the ratio of the moles

of O2 consumed and the concentration of the 2-oxoadipic acid present in the reaction. Each reaction condition was performed in triplicate. OXYGEN LABELING EXPERIMENTS All reagents were

exhaustively purged with argon on a Schlenk link to remove 16O2. Anaerobic buffer was subsequently saturated with 18O2 via gentle bubbling with 18O2 (Sigma, 99 atom % 18O). Reaction mixtures

containing enzyme (1 µM), 2-oxoadipic acid (1 mM), FeSO4 (10 µM), and 18O2 saturated buffer (1.2 mM) were mixed in anaerobic sealed reaction vials using gastight syringes. The reaction was

initiated by the addition of 2-oxoadipic acid. The headspace was filled with 18O2 gas. Reactions were incubated at room temperature for 2 h before being quenched with an equal volume of

methanol. Control experiments, replacing 18O2 with 16O2, were run in parallel. Quenched reaction mixtures were analyzed by LC-MS. LC-MS ANALYSIS All in vitro reactions to be analyzed via

LC-MS were quenched with an equal volume of ice cold methanol and stored at −80 °C until analyses. Detection of 2OA and 2HG were described previously8. Briefly, HILIC-HRMS analysis was

performed using an Agilent Technologies 6510 Accurate-Mass Q-TOF LC-MS instrument using positive mode and an Atlantis HILIC Silica 5 µm column (150 × 4.6 mm) with a linear of 95 to 50%

acetonitrile (v/v) over 8 min in water with 40 mM ammonium formate, pH 4.5, at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. PLANT GROWTH _A. thaliana_ DUF1338 mutant, Salk_103299C, seeds were ordered from the

Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Columbus, OH, USA). Seeds were surface sterilized with 70% EtOH for 3 min, followed by a ten-minute submersion in 10% bleach solution, then rinsed

with sterile water three times. For soil germination, seeds were planted in Premier Pro-Mix mycorise pro soil, two seeds per well in a twenty-four well tray. Trays with seeds were then

stratified at 4 °C for 3 days, then grown in a Percival-Scientific growth chambers at 22 °C in 10/14-h light/dark short-day cycles with 60% humidity. After the formation of the full rosette,

plants were genotyped to confirm homozygosity for the mutation of interest. Primers were designed using the automated method from http://signal.salk.edu/cgi-bin/tdnaexpress, and genotyping

was done in accordance with a previously described protocol and diagrammed in Supplementary Fig. 1154. After confirmation of homozygous mutants, plants were moved into individual wells and

transferred to long-day conditions, 22 °C in 16/8-h light/dark cycles with 60% humidity, to induce flowering for seed collection. For germination on synthetic media, sterilized seeds were

plated on solid media supplemented with ½ Murashige and Skoog media base, 5% sucrose, 0.8% agar, and 10 μM gibberellic acid to induce germination. Plates with seeds were stratified at 4 °C

for 3 days then transferred to a Percival-Scientific growth chambers at 22 °C in 10/14-h light/dark short-day cycles with 60% humidity. SYNTHESIS OF 2-OXOHEXANOIC ACID Synthesis of

2-oxohexanoic acid was carried out as described previously55. Briefly, a solution of the Grignard reagent, prepared from 1-bromobutane (500 mg, 3.68 mmol) and the suspension of magnesium

(178 mg, 7.33 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was added dropwise under N2 atmosphere to a solution of diethyloxalate (487 mg, 3.33 mmol) in THF (4 mL) at −78 °C. After the addition was complete, the

reaction mixture was stirred at –78 °C for an additional 5 h. The reaction was quenched with 2 N HCl, the aqueous layer was extracted with ether, and the combined organic layer was washed

with brine, dried over MgSO4, and evaporated. The crude product was dissolved in acetic acid (20 mL) and conc. HCl (5 mL). After 11 h, the reaction was concentrated directly, and the residue

was purified by distillation under reduced pressure to give the pure product (203 mg, 43%) as a colorless oil. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 2.92 (t, 2H), 1.81–1.54 (m, 2H), 1.48–1.28 (m, 2H),

0.92 (t, 3H) (Supplementary Fig. 12). HISTOPATHOLOGY Seeds were imbibed in distilled water for 2 h with gently shaking and a small hole was cut in the seed coat with a surgical scalpel to

aid resin infiltration. Seeds were fixed in 4% formaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 50 mM PIPES buffer (pH 7) with gently pulling under vacuum for 10 min. Seeds were left in

fixative overnight at 4 °C, dehydrated in an ethanol gradient, and infiltrated with Technovit 7100 plastic resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Resin was infiltrated under gentle vacuum for 20 min followed by rotation at 4 °C overnight. Seeds were embedded in beam capsules and 4 μm thick sections were cut on an MR2 manual rotary

microtome (RMC Boeckeler) using a glass knife. Sections were stained with 0.02% (w/v) Toluidine blue-O for 30 s, then rinsed and mounted in distilled water. Images were captured on a Leica

DM6B microscope (Leica Biosystems Inc. Buffalo Grove, IL) equipped with a Leica DMC 4500 color camera using Leica Application Suite X (LASX) software. BIOINFORMATICS For mining of DUF1338

homologs in plants all the proteins from completed genomes with protein predictions available by september 2019 were retrieved from the GenBank FTP site. The homologs were searched in each

proteome with BlastP using Flo7 as query with a bit score cutoff of 150 and an e-value cutoff of E-12. The retrieved sequences were aligned using muscle56, and trimmed using jalview57. The

multiple sequence alignment was used for phylogenetic reconstruction suing IQ tree, the best amino acid substitution model was selected with ModelFinder implemented in IQtree58, branch

support was calculated using 10000 bootstrap generations Sequences of DUF1338 homologs were downloaded from Pfam (https://pfam.xfam.org/family/PF07063). To compare the 3D structure of HglS

with other protein structures we used VAST10. All alignments were done using the MAFFT-LINSI algorithm59, and alignments were compared with secondary structures and visualized using Easy

Sequencing in PostScrip (http://espript.ibcp.fr)60. Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with UCSF Chimera, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and

Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from NIH P41-GM10331152. Python scripts were developed to calculate conservation of “HHE” metal-binding triads and

R74 residues. Calculation of Shannon-Entropy for DUF1338 sequence conservation was carried out using the python library Protein Dynamics and Sequence Analysis (ProDy)61,62. Co-expression

analysis of _A. thalina_ transcripts was performed using the ATTED-II database63. REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting

Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY The atomic coordinates and structural factors of HglS without substrate, HglS in complex with substrate, and Flo7 in complex with substrate

have been deposited in the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (https://www.wwpdb.org/) with PDB ID codes of 6W1G, 6W1H, and 6W1K, respectively. Bacterial strains and plasmids are available upon

request from: https://registry.jbei.org/. The source data underlying Figs. 1d, g, h and Supplementary Figs. 3, 4a, b, 5b, and 10c are provided as a source data file. Source data are provided

with this paper. CODE AVAILABILITY All code used in data analysis will be made available upon request. Source data are provided with this paper. REFERENCES * Galili, G. New insights into

the regulation and functional significance of lysine metabolism in plants. _Annu. Rev. Plant Biol._ 53, 27–43 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Galili, G. & Höfgen, R.

Metabolic engineering of amino acids and storage proteins in plants. _Metab. Eng._ 4, 3–11 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Galili, G. & Amir, R. Fortifying plants with

the essential amino acids lysine and methionine to improve nutritional quality. _Plant Biotechnol. J._ 11, 211–222 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yang, Q.-Q. et al.

Biofortification of rice with the essential amino acid lysine: molecular characterization, nutritional evaluation, and field performance. _J. Exp. Bot._ 67, 4285–4296 (2016). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hartings, H., Lauria, M., Lazzaroni, N., Pirona, R. & Motto, M. The Zea mays mutants opaque-2 and opaque-7 disclose extensive changes in

endosperm metabolism as revealed by protein, amino acid, and transcriptome-wide analyses. _BMC Genom._ 12, 41 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Locatelli, S., Piatti, P., Motto, M.

& Rossi, V. Chromatin and DNA modifications in the Opaque2-mediated regulation of gene transcription during maize endosperm development. _Plant Cell_ 21, 1410–1427 (2009). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hildebrandt, T. M., Nunes Nesi, A., Araújo, W. L. & Braun, H.-P. Amino acid catabolism in plants. _Mol. Plant_ 8, 1563–1579 (2015). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Thompson, M. G. et al. Massively parallel fitness profiling reveals multiple novel enzymes in _Pseudomonas putida_ lysine metabolism. _MBio_ 10, e02577-18 (2019).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhang, L. et al. FLOURY ENDOSPERM7 encodes a regulator of starch synthesis and amyloplast development essential for peripheral endosperm

development in rice. _J. Exp. Bot._ 67, 633–647 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Madej, T. et al. MMDB and VAST+: tracking structural similarities between macromolecular

complexes. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 42, D297–D303 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Brownlee, J., He, P., Moran, G. R. & Harrison, D. H. T. Two roads diverged: the structure of

hydroxymandelate synthase from Amycolatopsis orientalis in complex with 4-hydroxymandelate. _Biochemistry_ 47, 2002–2013 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Serre, L. et al.

Crystal structure of _Pseudomonas fluorescens_ 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase: an enzyme involved in the tyrosine degradation pathway. _Structure_ 7, 977–988 (1999). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Di Giuro, C. M. L. et al. Chiral hydroxylation at the mononuclear nonheme Fe(II) center of 4-(S) hydroxymandelate synthase–a structure-activity relationship

analysis. _PLoS ONE_ 8, e68932 (2013). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * He, P. & Moran, G. R. Structural and mechanistic comparisons of the metal-binding

members of the vicinal oxygen chelate (VOC) superfamily. _J. Inorg. Biochem._ 105, 1259–1272 (2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Armstrong, R. N. Mechanistic diversity in a

metalloenzyme superfamily. _Biochemistry_ 39, 13625–13632 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Angelovici, R., Fait, A., Fernie, A. R. & Galili, G. A seed high-lysine trait is

negatively associated with the TCA cycle and slows down Arabidopsis seed germination. _N. Phytol._ 189, 148–159 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhu, X. & Galili, G. Increased

lysine synthesis coupled with a knockout of its catabolism synergistically boosts lysine content and also transregulates the metabolism of other amino acids in Arabidopsis seeds. _Plant

Cell_ 15, 845–853 (2003). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Aik, W., McDonough, M. A., Thalhammer, A., Chowdhury, R. & Schofield, C. J. Role of the jelly-roll fold

in substrate binding by 2-oxoglutarate oxygenases. _Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol._ 22, 691–700 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mertz, E. T., Bates, L. S. & Nelson, O. E.

Mutant gene that changes protein composition and increases lysine content of maize endosperm. _Science_ 145, 279–280 (1964). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Engqvist, M. K. M.

et al. Plant D-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase participates in the catabolism of lysine especially during senescence. _J. Biol. Chem._ 286, 11382–11390 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Chen, Y.-C. et al. N-hydroxy-pipecolic acid is a mobile metabolite that induces systemic disease resistance in Arabidopsis. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 115,

E4920–E4929 (2018). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wang, C. et al. Pipecolic acid confers systemic immunity by regulating free radicals. _Sci. Adv._ 4, eaar4509

(2018). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Návarová, H., Bernsdorff, F., Döring, A.-C. & Zeier, J. Pipecolic acid, an endogenous mediator of defense

amplification and priming, is a critical regulator of inducible plant immunity. _Plant Cell_ 24, 5123–5141 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Zabriskie, T. M.

& Jackson, M. D. Lysine biosynthesis and metabolism in fungi. _Nat. Prod. Rep._ 17, 85–97 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wade, M., Thomson, D. M. & Miflin, B. J.

Saccharopine: an Intermediate of L-Lysine biosynthesis and degradation in _Pyricularia oryzae_. _Microbiology_ 120, 11–20 (1980). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hammer, T., Bode, R. &

Birnbaum, D. Occurrence of a novel yeast enzyme, L-lysine epsilon-dehydrogenase, which catalyses the first step of lysine catabolism in _Candida albicans_. _J. Gen. Microbiol._ 137, 711–715

(1991). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hallen, A., Jamie, J. F. & Cooper, A. J. L. Lysine metabolism in mammalian brain: an update on the importance of recent discoveries.

_Amino Acids_ 45, 1249–1272 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wetmore, K. M. et al. Rapid quantification of mutant fitness in diverse bacteria by sequencing randomly bar-coded

transposons. _MBio_ 6, e00306–e00315 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Price, M. N. et al. Mutant phenotypes for thousands of bacterial genes of unknown

function. _Nature_ 557, 503–509 (2018). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Soksawatmaekhin, W., Kuraishi, A., Sakata, K., Kashiwagi, K. & Igarashi, K. Excretion and uptake of

cadaverine by CadB and its physiological functions in _Escherichia coli_. _Mol. Microbiol._ 51, 1401–1412 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Knorr, S. et al. Widespread

bacterial lysine degradation proceeding via glutarate and L-2-hydroxyglutarate. _Nat. Commun._ 9, 5071 (2018). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Grover, Z. &

Ee, L. C. Protein energy malnutrition. _Pediatr. Clin. N. Am._ 56, 1055–1068 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Wenefrida, I., Utomo, H. S., Blanche, S. B. & Linscombe, S. D. Enhancing

essential amino acids and health benefit components in grain crops for improved nutritional values. _Recent Pat. DNA Gene Seq._ 3, 219–225 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Le,

D. T., Chu, H. D. & Le, N. Q. Improving nutritional quality of plant proteins through genetic engineering. _Curr. Genom._ 17, 220–229 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * WHO.

_Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition_. https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/nutrientrequirements/WHO_TRS_935/en/ (World Health Organization, 2007). * Kawakatsu, T.,

Wang, S., Wakasa, Y. & Takaiwa, F. Increased lysine content in rice grains by over-accumulation of BiP in the endosperm. _Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem._ 74, 2529–2531 (2010). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Falco, S. C. et al. Transgenic canola and soybean seeds with increased lysine. _Biotechnology_ 13, 577–582 (1995). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Betrán, F. J.,

Bockholt, A., Fojt, F., Rooney, L. & Waniska, R. Registration of Tx802. _Crop Sci._ 43, 1891-a (2003). Article Google Scholar * Ham, T. S. et al. Design, implementation and practice of

JBEI-ICE: an open source biological part registry platform and tools. _Nucleic Acids Res_. 40, e141 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Chen, J., Densmore, D.,

Ham, T. S., Keasling, J. D. & Hillson, N. J. DeviceEditor visual biological CAD canvas. _J. Biol. Eng._ 6, 1 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hillson, N. J.,

Rosengarten, R. D. & Keasling, J. D. j5 DNA assembly design automation software. _ACS Synth. Biol._ 1, 14–21 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gibson, D. G. et al.

Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. _Nat. Methods_ 6, 343–345 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Engler, C., Kandzia, R. & Marillonnet, S. A

one pot, one step, precision cloning method with high throughput capability. _PLoS ONE_ 3, e3647 (2008). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Yan, P., Gao, X., Shen,

W., Zhou, P. & Duan, J. Parallel assembly for multiple site-directed mutagenesis of plasmids. _Anal. Biochem._ 430, 65–67 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Jancarik, J.

& Kim, S. H. Sparse matrix sampling: a screening method for crystallization of proteins. _J. Appl. Crystallogr._ 24, 409–411 (1991). Article CAS Google Scholar * McCoy, A. J. et al.

Phaser crystallographic software. _J. Appl. Crystallogr_. 40, 658–674 (2007). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Afonine, P. V. et al. Towards automated crystallographic

structure refinement with phenix.refine. _Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr._ 68, 352–367 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K.

Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. _Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr._ 60, 2126–2132 (2004). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a

comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. _Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr._ 66, 213–221 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Davis, I. W. et al. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 35, 375–383 (2007). Article ADS Google Scholar * The PyMOL

Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC. at https://pymol.org/2/. * Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. _J.

Comput. Chem._ 25, 1605–1612 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Witkowski, A., Joshi, A. K. & Smith, S. Mechanism of the β-ketoacyl synthase reaction catalyzed by the animal

fatty acid synthase. _Biochemistry_ 41, 10877–10887 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Alonso, J. M. et al. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of _Arabidopsis thaliana_.

_Science_ 301, 653–657 (2003). Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Rapf, R. J. et al. Photochemical synthesis of oligomeric amphiphiles from alkyl oxoacids in aqueous environments. _J.

Am. Chem. Soc._ 139, 6946–6959 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput.

_Nucleic Acids Res._ 32, 1792–1797 (2004). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Waterhouse, A. M., Procter, J. B., Martin, D. M. A., Clamp, M. & Barton, G. J. Jalview

Version 2–a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. _Bioinformatics_ 25, 1189–1191 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt,

H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. _Mol. Biol. Evol._ 32, 268–274 (2015). Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. _Mol. Biol. Evol._ 30, 772–780

(2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Robert, X. & Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. _Nucleic Acids Res._

42, W320–W324 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bakan, A. et al. Evol and ProDy for bridging protein sequence evolution and structural dynamics.

_Bioinformatics_ 30, 2681–2683 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bakan, A., Meireles, L. M. & Bahar, I. ProDy: protein dynamics inferred from theory and

experiments. _Bioinformatics_ 27, 1575–1577 (2011). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Obayashi, T., Aoki, Y., Tadaka, S., Kagaya, Y. & Kinoshita, K. ATTED-II in

2018: a plant coexpression database based on investigation of the statistical property of the Mutual Rank Index. _Plant Cell Physiol._ 59, e3 (2018). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank Johan Jaenisch for generously providing _A. thaliana_ cDNA. Python code to analyze kinetics data was provided by Sam Curran. This

work was part of the DOE Joint BioEnergy Institute (https://www.jbei.org) supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and

was part of the Agile BioFoundry (http://agilebiofoundry.org) supported by the US Department of Energy, Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Bioenergy Technologies Office, through

contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 between Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the US Department of Energy. J.M.B.H. was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research

Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE 1106400. The Advanced Light Source is a Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. The Berkeley Center

for Structural Biology is supported in part by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The ALS-ENABLE beamlines are supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of

General Medical Sciences, grant P30 GM124169. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the US Department of Energy,

Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and

Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41GM103393). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility

of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the

United States Government or any agency thereof. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes

any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not

infringe privately owned rights. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Mitchell G. Thompson, Jacquelyn M. Blake-Hedges, Jose Henrique Pereira. AUTHORS AND

AFFILIATIONS * Joint BioEnergy Institute, Emeryville, CA, USA Mitchell G. Thompson, Jacquelyn M. Blake-Hedges, Jose Henrique Pereira, Michael S. Belcher, William M. Moore, Jesus F. Barajas,

Pablo Cruz-Morales, Lorenzo J. Washington, Robert W. Haushalter, Christopher B. Eiben, Yuzhong Liu, Veronica T. Benites, Edward E. K. Baidoo, Henrik V. Scheller, Patrick M. Shih, Paul D.

Adams & Jay D. Keasling * Biological Systems & Engineering Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA Mitchell G. Thompson, Jacquelyn M. Blake-Hedges, Michael

S. Belcher, William M. Moore, Jesus F. Barajas, Pablo Cruz-Morales, Lorenzo J. Washington, Robert W. Haushalter, Christopher B. Eiben, Yuzhong Liu, Veronica T. Benites, Edward E. K. Baidoo,

Henrik V. Scheller, Patrick M. Shih & Jay D. Keasling * Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California-Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA Mitchell G. Thompson, Michael S.

Belcher, William M. Moore, Lorenzo J. Washington, Tyler P. Barnum & Henrik V. Scheller * Department of Chemistry, University of California-Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA Jacquelyn M.

Blake-Hedges, John A. Hangasky, Will Skyrud & Michael A. Marletta * Molecular Biophysics and Integrated Bioimaging, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA Jose Henrique

Pereira & Paul D. Adams * Department of Energy Agile BioFoundry, Emeryville, CA, USA Jesus F. Barajas * Department of Bioengineering, University of California-Berkeley, Berkeley, CA,

94720, USA Christopher B. Eiben, Paul D. Adams & Jay D. Keasling * Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of California-Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA Michael A. Marletta

* Department of Plant Biology, University of California-Davis, Davis, CA, USA Patrick M. Shih * Genome Center, University of California-Davis, Davis, CA, USA Patrick M. Shih * Environmental

Genomics and Systems Biology Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA Patrick M. Shih * Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of

California-Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA Jay D. Keasling * The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Biosustainability, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark Jay D. Keasling * Center

for Synthetic Biochemistry, Shenzhen Institutes for Advanced Technologies, Shenzhen, China Jay D. Keasling Authors * Mitchell G. Thompson View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jacquelyn M. Blake-Hedges View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jose Henrique Pereira View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * John A. Hangasky View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Michael S.

Belcher View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * William M. Moore View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Jesus F. Barajas View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Pablo Cruz-Morales View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lorenzo J. Washington View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Robert W. Haushalter View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Christopher B. Eiben View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yuzhong Liu View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Will Skyrud View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Veronica

T. Benites View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tyler P. Barnum View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Edward E. K. Baidoo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Henrik V. Scheller View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Michael A. Marletta View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Patrick M. Shih View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Paul D. Adams View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jay D. Keasling View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Conceptualization, M.G.T., J.M.B.H., and J.H.P.; Methodology, M.G.T., J.M.B.H., J.H.P., J.F.B., P.C.M.,

E.E.K.B., J.A.H., W.M.M., M.S.B., and Y.L.; Investigation, M.G.T., J.M.B.H., J.H.P., V.T.B., J.A.H., M.S.B., W.M.M., L.J.W., T.P.B., W.S., R.W.H., C.B.E., E.E.K.B., and Y.L.; Writing –

Original Draft, M.G.T, J.M.B.H., and J.H.P.; Writing – Review and Editing, All authors; Resources and supervision H.V.S., P.M.S., M.A.M., P.D.A., and J.D.K. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Correspondence to Jay D. Keasling. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS J.D.K. has financial interests in Amyris, Lygos, Demetrix, Napigen, Maple Bio, Apertor Labs and Ansa Biotechnology.

All other authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks Tatjana Hildebrandt, Graham Moran, and Jing-Ke Weng for their

contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and

institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION DESCRIPTION OF ADDITIONAL SUPPLEMENTARY FILES SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 1 PEER REVIEW FILE REPORTING SUMMARY SOURCE

DATA SOURCE DATA RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation,

distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and

indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to

the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

CITE THIS ARTICLE Thompson, M.G., Blake-Hedges, J.M., Pereira, J.H. _et al._ An iron (II) dependent oxygenase performs the last missing step of plant lysine catabolism. _Nat Commun_ 11, 2931

(2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16815-3 Download citation * Received: 17 March 2020 * Accepted: 21 May 2020 * Published: 10 June 2020 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16815-3 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative