- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT STUDY DESIGN Cross-sectional explorative observational study. OBJECTIVES To identify factors which have an association to the self-perceived Quality of Life (QoL) for persons with

acquired spinal cord injury (SCI). SETTING Eight specialized SCI-centers in Germany. The GerSCI survey is the German part of the International Spinal Cord Injury Survey (InSCI). METHODS

Self-disclosure questionnaire, created from the InSCI group, translated and adapted for Germany. The questionnaire collects a very broad range of data and, and due to its design as a

self-report, is particularly suitable for the analysis on QoL. Because of the content, which is binding for all participating states, it allows a direct comparability of the results.

Included in Germany were 1479 persons with acquired SCI aged 18 years and older. RESULTS Various factors were identified with high associations to QoL, including changeable and unchangeable

ones, such as those of particular importance: pain, sleep problems, sexual dysfunction, age, and time since onset of SCI. Some results confirmed reports of previous studies, others were

surprising. CONCLUSION this study provides an important basis for the planned analysis of the InSCI participating countries in the 6 WHO regions. Germany was able to contribute the largest

study population. The concrete study design of InSCI allows us to directly compare data and helps us to improve ourselves within the framework of a “learning health system”. Medical measures

can be orientated towards the found results, in order to ensure the best possible care and support by the therapeutic team, individually adapted to the person, place of residence and

impairment. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PREDICTORS OF QUALITY OF LIFE OF INDIVIDUALS LIVING IN BRAZIL WITH SPINAL CORD INJURY/DISEASE Article 16 February 2023 AUSTRALIAN ARM OF

THE INTERNATIONAL SPINAL CORD INJURY (AUS-INSCI) COMMUNITY SURVEY: 2. UNDERSTANDING THE LIVED EXPERIENCE IN PEOPLE WITH SPINAL CORD INJURY Article Open access 15 June 2022 THE MOORONG SELF

EFFICACY SCALE: TRANSLATION, CULTURAL ADAPTATION, AND VALIDATION IN ITALIAN; CROSS SECTIONAL STUDY, IN PEOPLE WITH SPINAL CORD INJURY Article 16 February 2022 INTRODUCTION CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

ABOUT QUALITY OF LIFE WITH SCI The life expectancy of patients after SCI has increased significantly almost everywhere in the world due to better acute medical care, although there are still

large international differences [1]. For this very reason, a good acute and rehabilitative care including life-long treatment under consideration of the quality of life are becoming

increasingly important. While economic evaluations typically embrace health maximization as the maximization objective, using quality-adjusted life years, there is increasing interest in

measuring capability well-being and subjective well-being for informing policy decision-makers [2]. In recent years, there have been a large amount of studies that have looked at, among

other things, the impact on the quality of life of people with SCI. Only a few of the more newer ones can be named here as examples that attempt to reflect the state of knowledge. Factors

that seem to have a particularly high association are pain and spasticity [3,4,5,6], as well as bladder and bowel function [7,8,9]. Sexual dysfunction also seems to have an association to

QoL [6, 10, 11]. Studys and already meta-analysis showed the high impact to QoL of the psychological aspects. Greater acceptance of SCI, life satisfaction, level of depression and anxiety

have associations to QoL [6, 12,13,14,15,16]. A great influence on the mental status seems to have the participation in social life [6, 16]. Healthy SCI individuals tend to have better QoL

measures and secondary health issues after SCI are affecting QoL and social participation [17]. Older studies, but also very recent ones, confirm that the quality of life of adults with

chronic SCI was lower compared with reference populations [6, 18]. In the past, it was already regretted that there was no single definition of Quality of Life that everyone agreed upon,

largely due to the breadth of literature that addressed this topic and the varying definitions used in studies [19]. This, too, makes it difficult to compare results between populations or

different states. International research projects such as InSCI could help to ensure that there is a uniform definition at some time. INTERNATIONAL BACKGROUND Both the United Nations (UN)

and the World Health Organization (WHO) demand the collection of internationally comparable data on the living and care situation of people with disabilities [20]. Consequently, the

International Spinal Cord Injury Survey (InSCI) was launched, headed by the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS) and the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine

(ISPRM), within the framework of the WHO Collaboration Plan and the coordination of Swiss Paraplegic Research (SPF). The aim of the InSCI is for health systems to learn from each other

through the comparison of results of the 22 participating countries in all 6 WHO regions. The outcomes should also help to develop recommendations for decision-makers in politics and health

care [21]. Furthermore, reliable national data are also required to ensure optimal care and supply [22]. Germany is one of the participating countries to collect these requested data to

compare within InSCI. In Germany the project is called “German Spinal Cord Injury Survey (GerSCI)”. One special advantage of the InSCI survey is, that the persons concerned are asked about

their point of view and their perceived situation. Therefore, this data collection is particularly suitable for the analysis of the factors potentially influencing perceived Quality of Life

(QoL). SPECIAL ASPECTS OF THIS STUDY One of the first results of the GerSCI study was that, for persons with SCI, QoL decreased with increasing experience of barriers. Some of these aspects

have already been highlighted by our study group [23], but it became clear that for this important topic of QoL a specific analysis of the different probably influencing factors was

necessary. Therefore, we wanted to look at the different factors individually and try to put them into a clinical context. In literature, a number of comprehensive questionnaires to assess

QoL are available. They are based on diverse constructs of QoL and focus mainly on health-related performance in daily life. Another approach refers to a more general feeling of the

subjective perception of life quality. Of course, subjective perception has multiple dimensions but also is related to the individual’s values and life goals. For pragmatic reasons and

because the use of complex and extended questionnaires in our study would have led to be not user-friendly we decided to use a commonly used single question to get a rough estimate of

subjective level of QoL. The evaluation of separate components and the differentiation between various constructs of functioning should be the subject of future studies.The specific aims of

this study were: (i) to describe the level of Quality of Life in the German study population and (ii) to identify and describe the probability of influence on covariates of Quality of Life.

(iii) to provide a basis for international comparison within InSCI. METHODS The German Spinal Cord Injury Survey (GerSCI) data set, as the German part of InSCI, served as the basis for the

study. The used questionnaire was developed centrally by the InSCI study group and is thus binding for all InSCI participating countries. It has been shown, that the successful

implementation of the InSCI survey enables the comparison of the situation of individuals with SCI in different regions around the world and constitutes a crucial starting point for an

international learning experience [24]. GerSCI was implemented in 2017 and was conducted by the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine at Hannover Medical School. INCLUSION CRITERIA: *

Presence of acquired SCI (traumatic or non-traumatic) * Age ≥ 18 years * Completed post-acute rehabilitation: 12 months after the onset of the spinal cord lesion * Current place of

residence: Germany, language competence: German EXCLUSION CRITERIA: * Congenital SCI or neurodegenerative diseases From the database of the eight participating specialized SCI centers, 5,598

potential participants were identified. They were treated at least once in one of these specialized SCI clinics inpatient or outpatient. They received an invitation letter and the

questionnaire, which they could answer in paper form or electronically. After the exclusion of questionnaires that failed to satisfy the inclusion criteria, the available participant data

declined by _n_ = 79. Some were excluded due to aborted online questionnaires (_n_ = 56), received duplicate questionnaires (_n_ = 2) and > 30 % of missing values (_n_ = 138). 1479

questionnaires were considered for data evaluation [25]. The potential influence of various factors on QoL were studied using measurements of association. SURVEY INSTRUMENTS MEASURING

QUALITY OF LIFE (WHOQOL-BREF) The WHOQoL-BREF is an instrument for recording subjective QoL. It is based on the definition of QoL, as the perception of one’s own life situation in the

context of respective culture and value systems, as well as in relation to individual goals, expectations, and interests. We use the term QoL to refer to the perceived, purely subjective

experience of the participants, in order to reflect their individual perspective in this study. We relate this statement to perceived barriers and enabling factors. The WHOQoL-BREF

questionnaire consists of 26 items that focus on several dimensions, such as physical well-being, psychological well-being, social relationships, and environment [26]. Six items were used

from the WHOQoL-BREF in the GerSCI questionnaire. These items were predetermined by the InSCI study group. Since there is no reliable sum score of this question selection given by the InSCI

team, we chose the overall QoL assessment as the primary target criterion. However, regarding this study, the item which was used for associations as the main parameter was, “How would you

rate your quality of life in the last 30 days?”, which were rated on a scale with five ratings from “very poor” to “very good”. Since not the complete WHOQoL-Bref was used in this

questionnaire, we were able to create the WHOQoL-Bref global domain score with the first and second question using a scale transformation (0–100). This scale transformed global domain values

were then compared to the general population in the year 2000 according to Angermeyer et al. [27]. Unfortunately, no matched and more recent comparison sample is available from Germany.

COVARIATES The selection of the covariates within the framework of the InSCI questionnaire was made based on the literature reports described in the introduction and expert discussion within

the GerSCI team about possible additional relevant factors. In order to analyze for associations, sociodemographic data and lesion characteristics were used, including age, gender,

relationship status, level of injury (paraplegia vs tetraplegia), injury severity (complete vs incomplete), time since injury, etiology (traumatic vs non-traumatic), satisfaction with

community health services (satisfied vs not satisfied), difficulties gaining medical aids (no vs yes), employment status (unemployed vs employed), education level (low vs high), net

household income (under average vs over average) and health conditions (no vs yes: sleep problems, bowel dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, contractures, decubitus, urinary bladder function,

bladder infection, spasticity, respiratory problems, injuries due to sensory disorders, circulatory problems or circulatory disorders, dysreflexia, orthostatic hypotension, diabetes

mellitus, periarticular ossification), and pain (no to mild, and moderate to severe). The five rating categories of the WHOQoL-Bref were dichotomized into “0”, which corresponded with “very

bad”, “bad” and “mediocre” and “1”, which corresponded with “well” and “very good”. The pain-scale with rating categories 0 to 10 was convertes in a dummy variable according to Ledowski et

al. in 0–3 = _no to mild pain_ and 4–10 = _moderate to severe pain_ [28]. Education status was converted in a dummy variable as 1 = no school leaving certificate, primary school certificate,

lower secondary graduation, secondary school graduation, and 2 = advanced technical college entrance qualification, Abitur (general university entrance qualification). Satisfaction with

community health service was converted in a dummy variable as 1 = “very satisfied”, “satisfied” and 2 = “neither” or, “unsatisfied”, “very unsatisfied”. Net household income was categorized

into 1 = “less than 981 €, 982–1345 €, 1346–1660 €, 1661–1990 €, 1991–2339 €, 2340–2732 €, 2337–3195 €”, and 2 = “3196–3819 €, 3820–4837 €, more than 4838 €” according to average monthly net

income per private household in Germany [29]. Problematic health conditions during the last three months were rated on a 5 point Likert scale from “not problematic” until “extremely

problematic”. In this analysis, we dichotomized the scale in 0 = “no problem” and 1 = “a little problematic” till “extremely problematic”. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Sociodemographic data and SCI

characteristics were presented as percentages or means with standard deviation (SD). The key focus of this study was the QoL of people with SCI in Germany. WHOQoL-Bref frequencies were

presented as percentages. Only the data from participants with less than 30% missing values were included in the statistical analysis. To analyze associations between QoL covariates,

associations using Eta and Cramers’V were calculated. The determinants of QoL covariates associated with the perception of a high quality of life were assessed using multivariable logistic

regression and estimated odds ratios (OR) with a 95% Confidence interval (CI). Variables were included if they showed significant associations to QoL, which were all variables except marital

status. The proportion of missing values was less than 5%, therefore no imputation of missing values has been performed. Results were considered statistically significant if _p_ values were

less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS IBM 26.0. RESULTS The average age of the respondents was 55.3 years (SD: 14.6). The range was from 19 to 90 years. 51,2 %;

stated a paraplegia; 48,8 % a tetraplegia. Further details of socio-demographic and lesion characteristics of study participants are available elsewhere [23]. Most respondents answered the

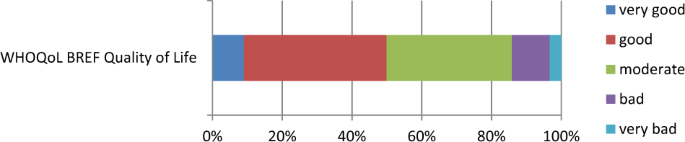

question “How would you rate your quality of life in the last 30 days?” with “good” (41%) to “moderate” (36%). A smaller proportion described it as “bad” (11%) or “very bad” (3.3%). A “very

good” quality of life was reported by 9.0% (Fig. 1). Fig. 2 shows the comparison of the QoL of the study population in relation to the available norm sample [27]. With regard to the age

groups, it can be seen that the values of the norm sample are higher than the values of the study population in all age groups. In the age group > 85 years they are almost the same. For

almost all values selected from clinical experience and literature research, the association analysis showed a high significance with the development of QoL of _p_ < 0.05, and most of

them were even _p_ < 0.001 (Tables 1 and 2). Due to this high levels of significance of most of the chosen factors, it is important to consider the effect size in order to assess the

relevance of the factors. The largest effect size with Cramers’ V above 0.30 (Interpretation of Cramér’s V according to Cohen: small = 0.10; medium = 0.30; large = 0.50) were for pain, sleep

problems, and sexual dysfunction. Even this does not say anything statistically accurate about the absolute level of association. A logistic regression analysis shows that both the model as

a whole (chi-square(27) = 249.695, _p_ < 0.001) and some of the individual coefficients of the variables are significant. The R-square after Nagelkerke is 0.403, which explains 40.3% of

the regression model. The results of the logistic regression are displayed in Table 3. A higher relative probability of experiencing a good QoL is linked to people who are satisfied with

their community health services (OR = 1.730; _p_ = 0.013), those who have no difficulties in gaining medical aids (OR = 2.176; _p_ < 0.001), who have no bowel dysfunction (OR = 1.774; _p_

= 0.023), no sexual dysfunction (OR = 1.969; _p_ = 0.027), no contractures (OR = 1.626; _p_ = 0.032), no to mild pain (OR = 3.289; _p_ < 0.001) and no diabetes mellitus (OR = 2.013; _p_

= 0.039). Those who are unemployed (OR = 0.562; _p_ = 0.004) have a higher relative probability of not experiencing a high QoL compared to employed participants. Converted from the data it

can be concluded that with every year of life, the relative probability of a good QoL decreases by 3.1% and increases by 2.4% with each additional year of occurrence of SCI. DISCUSSION The

study showed that there are some physical impairments that seem to have particularly high influence on QoL. Particularly noteworthy are pain, contractures, bowel and sexual dysfunction. Some

social factors also show high associations with perceived QoL, such as employment, being satisfied with their community health services and having no difficulties in gaining medical aids.

The results largely confirm trends seen earlier, but some results also contradict the previous findings. We will focus on the factors that showed the highest effect sizes. Impairment

factors, like lesion height and completeness of lesion, were of lower significance in the association to reported QoL in this survey. A comparison of the literature showed that contradictory

statements have already been made in this regard in the past. It has already been reported that, as in our case, there were no relevant association [30], others reported more indirect

associations to QoL via physical functioning [31, 32]. Other findings showed that the level of injury in people with SCI had a high impact on their QoL, suggesting that these people need

adaptive and compensatory equipment to improve their QoL [33, 34]. Maybe the influence on QoL depends on the technical possibilities for rehabilitation and support in the country of origin

of the studies, as these results were reported from Iran and Bangladesh. But also in Canada with high level medical support the injury severity indicated via the physical functioning

influence on QoL [32]. Other studys found now significant influence directly to QoL and also referred to indirect effects via physical function and participation [31]. The meaning of the

relationship status still seems unclear in relation to other results so far. With _p_ = 0.262 there was no significant association to the overall QoL. However, there were contradictory

trends on this in earlier reports about the impact on QoL. In a survey of people with SCI for global meaning, the participants named relationship status as one of the five most important

factors [35]. Results from Greece showed married life as associated with higher QoL levels (_p_ = 0.006) [36]. In Canada it was reported, that being married positively affected life

satisfaction [32]. It can be assumed that there are parallels between global meaning, life satisfaction and QoL. However, comparability is limited because the terms describe different

nuances in the self-assessment of personal status. In another comparison of 6 different countries, there was no association of the relationship status with QoL [31]. The largest effect size

with Cramers’ V (>0,3) showed up for pain, sleep problems, and sexual dysfunction. We also want to go into more detail about some of the other factors that showed high effect sizes in the

analysis. Pain has already shown its high influence on QoL in the literature. One of the studies demonstrated that despite all previous efforts, the presence, complexity, and stability of

pain symptoms were refractory to treatment and produced lower QoL ratings in persons with chronic SCI [37]. Several types of pain typically occur in SCI, with central neuropathic pain being

a frequent and difficult to manage occurrence [38]. The cyclical relationship of musculoskeletal pain, reduced activity, and maladaptive psychological factors allude to the interdependence

of factors, supporting the multidisciplinary approach to care [39]. More precise causes of still high pain levels cannot be deduced from this self-report questionnaire Sleep problems are a

known problem since years. For example in an analysis from Switzerland in 2011 individuals with SCI reported more sleep problems compared to the general Swiss population. This study suggests

that clinical screening for sleep issues targeting high-risk groups is needed to reduce the large prevalence of non-treatment in individuals with SCI [40]. The results of the survey do not

show us whether the problems are more about falling asleep or staying asleep. However, the causes of sleep disturbances can be various. Psychological problems can cause them just as much as

pain, digestive disorders, or sensations in the extremities. Sexual dysfunction has a high association to QoL and is particularly interesting from a clinical point of view, since it is

already known from another analysis of our data that although sexual dysfunction often exist they are nevertheless rarely under medical treatment, or that patients do not seek medical advice

for this issue [41]. There may be an issue where QoL can be practically improved through medical assistance. The logistic regression results are clinically interesting, because they show

the probability of experiencing a high QoL in relation to this variables. In addition to the mentioned factors above, there were some more variables worth a consideration. Bowel dysfunction

and diabetes mellitus are challenges for treatment by health professionals. While the influence of bowel dysfunctions is obvious, diabetes is more likely to affect QoL through secondary

diseases such as polyneuropathy, or the need for medication such as insulin injections. Unfortunately, multimorbidity is common, with 59.1% of individuals with SCI [32]. The influence of

existing contractures on QoL is important to bear in mind. Targeted and multimodal therapy with physiotherapeutic measures, pharmaceutical support and, if necessary surgical release may be

required. Being satisfied with their community health services and having no difficulties in gaining medical aids showed a high odds ratio. This confirms the high value for people with SCI

of a good rehabilitation system and generous technical support. The importance has been reported before: technology plays a critical role in promoting well-being, activity, and participation

for individuals with SCI. This ranges from lighter wheelchairs to new software, which makes computer interfaces adaptive [42]. Perhaps the importance of the health system and the technical

support is also the reason why there are so many differences in QoL between countries. For instance in a study with data from Australia, Brazil, Canada, Israel, South Africa, and the United

States of America, analysis of variance showed that living in Brazil was a significant predictor of lower QoL. The differences between the countries could not be explained by differences in

demographic and lesion-related characteristics. The results point to the relevance of reintegration of people with SCI into the workforce [31]. Many factors could account for this

differences, one could be varying degrees of technical support in the different countries. As unemployment has been shown to be a risk factor for low QoL, vocational support measures are

also an important option and should be implemented early in the rehabilitation strategy. Further discussion on this point has already been published by our study group [43]. However, work

can also have a negative influence if it is overstrained. Cross-sectional data from 386 employed men and women with SCI from the Netherlands, Switzerland, Denmark, and Norway were analyzed

and work stress and low job control was linked to decreased general QoL [44]. The results regarding age and time since the onset of SCI were largely consistent with previous studies.

Declining QoL coincides in the normal population with increasing age. That time elapsed since the onset of SCI mostly means a higher QoL is usually attributed to a higher acceptance and

better adaptation to the functional impairments due to acquired SCI [31, 34, 36, 45]. However, there have also been results where QoL did not deteriorate with increasing age. In these

studies, it was considered that the positive aspects of getting used to SCI outweighed the general trend of decreasing QoL with age [39]. STRENGTHS A major advantage of this analysis is the

questionnaire, which asks very broadly about many aspects of daily life. It was developed centrally by the InSCI study group and is thus binding for all InSCI participating countries. This

allows a direct comparison between countries of all different WHO regions. This can facilitate the discussion of differences and promote improvements in the context of a “learning health

system”. Another advantage is the largest study population (_n_ = 1479) of all participating countries within InSCI. LIMITATIONS The recruiting strategy included possible selection bias

because all invited persons were treated at least once in one of the specialized SCI clinics. It is possible (and even probable), that the supply situation of persons with SCI who have not

been treated in such a center is even worse. The response rate of 32.6% was acceptable but not very high compared to some other surveys. This could be caused by the extensive questionnaire.

Another selection bias is possible because answering the questionnaire itself is a challenge for people’s mental ability and motor activity. This may have excluded people who were severely

impaired and had no personal assistance to fill in. Regarding the interpretation, it must be taken into account that QoL was assessed only on the basis of one question about the perceived

overall situation of QoL and this only according to the last 30 days. Seasonal deviations for example are not recorded with it. In the regression model about 40 % could be explained. This is

statistically a good value, but it also shows us that we cannot yet fully explain many associations and, above all, interactions of variables. The dichotomisation of the variables could

possibly lead to a distortion of the results. CONCLUSION The results of this study provide many indications, but these must certainly be examined in more detail in further studies to

determine the cause and options for improvement. However, multifarious factors have been identified that show a high association with the perceived and reported general QoL. From a medical

point of view, these are particularly important, as they are modifiable and can lead to practical consequences for possible adjustments of support or medical measures. The importance of a

good health care system with adapted rehabilitation and specific support is emphasized by the described complaints and needs. However,the measures must also be adjusted to the financial and

infrastructural possibilities of the region in question. It remains important to work closely with each individual person with SCI, since only as a team with doctors, therapists, and

technicians, supported by social or political measures, can the goal of providing the best possible care be achieved. Only then can barriers be broken down, impairments reduced, and the

Quality of Life noticeably improved. DATA AVAILABILITY The original data are available on request to Mrs. Bökel, Hannover Medical School, Germany or at the InSCI Study Center at the Swiss

Paraplegic Center, Nottwil, Switzerland. REFERENCES * Thietje R. Epidemiologie, Ätiologie und Mortalität bei Querschnittlähmung. Neuroreha. 2016;08:105–9.

https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-112079 Article Google Scholar * Engel L, Bryan S, Noonan VK, Whitehurst DGT. Using path analysis to investigate the relationships between standardized

instruments that measure health-related quality of life, capability wellbeing and subjective wellbeing: An application in the context of spinal cord injury. Soc Sci Med. 2018;213:154–64.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.041 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Andresen SR, Biering-Sørensen F, Hagen EM, Nielsen JF, Bach FW, Finnerup NB. Pain, spasticity and quality

of life in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury in Denmark. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:973–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.46 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nagoshi N, Kaneko

S, Fujiyoshi K, Takemitsu M, Yagi M, Iizuka S, et al. Characteristics of neuropathic pain and its relationship with quality of life in 72 patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord.

2016;54:656–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.210 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Burke D, Lennon O, Fullen BM. Quality of life after spinal cord injury: the impact of pain. Eur J

Pain. 2018;22:1662–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1248 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chang F, Xie H, Zhang Q, Sun M, Yang Y, Chen G, et al. Quality of life of adults with chronic

spinal cord injury in mainland china: A cross-sectional study. J Rehabil Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2689. * Nevedal A, Kratz AL, Tate DG. Women’s experiences of living with

neurogenic bladder and bowel after spinal cord injury: life controlled by bladder and bowel. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:573–81. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1049378 Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Theisen KM, Mann R, Roth JD, Pariser JJ, Stoffel JT, Lenherr SM, et al. Frequency of patient-reported UTIs is associated with poor quality of life after spinal cord injury:

a prospective observational study. Spinal Cord 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0481-z. * Rofi’i AYAB, Maria R, Masfuri. Quality of life after spinal cord injury: an overview.

Enferm Clin. 2019;29 Suppl 2:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2019.05.001. Suppl 2. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Merghati-Khoei E, Emami-Razavi SH, Bakhtiyari M, Lamyian M,

Hajmirzaei S, Ton-Tab Haghighi S, et al. Spinal cord injury and women’s sexual life: case-control study. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:269–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.106 Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Stoffel JT, van der Aa F, Wittmann D, Yande S, Elliott S. Fertility and sexuality in the spinal cord injury patient. World J Urol. 2018;36:1577–85.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-018-2347-y Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * van Leeuwen CMC, Kraaijeveld S, Lindeman E, Post MWM. Associations between psychological factors and quality

of life ratings in persons with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:174–87. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2011.120 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Peterson MD,

Kamdar N, Chiodo A, Tate DG Psychological morbidity and chronic disease among adults with traumatic spinal cord injuries: a longitudinal cohort study of privately insured beneficiaries. Mayo

Clin Proc. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.11.029. * Eaton R, Jones K, Duff J. Cognitive appraisals and emotional status following a spinal cord injury in post-acute

rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:1151–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0151-6 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Aaby A, Ravn SL, Kasch H, Andersen TE. The associations of

acceptance with quality of life and mental health following spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2020;58:130–48. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0379-9 Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Müller R, Landmann G, Béchir M, Hinrichs T, Arnet U, Jordan X, et al. Chronic pain, depression and quality of life in individuals with spinal cord injury: mediating role of

participation. J Rehabil Med. 2017;49:489–96. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2241 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Frontera JE, Mollett P. Aging with spinal cord injury: an update. Phys

Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2017;28:821–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2017.06.013 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Lidal IB, Veenstra M, Hjeltnes N, Biering-Sørensen F. Health-related

quality of life in persons with long-standing spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:710–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2008.17 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Charlifue S, Post MW,

Biering-Sørensen F, Catz A, Dijkers M, Geyh S, et al. International spinal cord injury quality of life basic data set. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:672–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.27 Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales. Zweiter Teilhabebericht der Bundesregierung über die Lebenslagen von Menschen mit Beeinträchtigungen. 2016.

https://www.bmas.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/PDF-Publikationen/a125-16-teilhabebericht.pdf;jsessionid=FC8AE05EC6FAFA6CB9F5ACB5C08794F0?__blob=publicationFile&v=9. Accessed 12 Aug 2020. *

Gross-Hemmi MH, Post MWM, Ehrmann C, Fekete C, Hasnan N, Middleton JW, et al. Study Protocol of the International Spinal Cord Injury (InSCI) Community Survey. Am J Phys Med Rehabil.

2017;96:S23–S34. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000000647 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Bickenbach J, Officer A, Shakespeare T, Groote P von. International Perspectives on Spinal

Cord Injury. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. * Bökel A, Dierks M-L, Gutenbrunner C, Weidner N, Geng V, Kalke Y-B, et al. Perceived environmental barriers for people with spinal cord

injury in Germany and their influence on quality of life. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52:jrm00090 https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2717 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Fekete C, Brach M, Ehrmann

C, Post MWM, Stucki G Cohort Profile of the International Spinal Cord Injury Community Survey Implemented in 22 Countries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2020.01.022. * Bökel A, Blumenthal M, Egen C, Geng V, Gutenbrunner C Querschnittlähmung in Deutschland: Eine nationale Befragung (German Spinal Cord Injury

Survey (GerSCI) Teilprojekt des Spinal Cord Injury Community Survey (InSCI)): Medizinische Hochschule Hannover Bibliothek. * Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality

of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med 1998;28:551–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291798006667. Article Google Scholar * MC Angermeyer, R Kilian, H Matschinger. WHOQOL-100 and

WHOQOL-BREF. Handbook of the German Version of the WHO Instrument to Assess Quality of life: Handbook of the German Version of the WHO Instrument to Assess Quality of life; 2000. * Ledowski

T, Bromilow J, Paech MJ, Storm H, Hacking R, Schug SA. Monitoring of skin conductance to assess postoperative pain intensity. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:862–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/ael280.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rudnicka J Statistiken zu Haushalten in Deutschland. 2020. * Middleton J, Tran Y, Craig A. Relationship between quality of life and self-efficacy in

persons with spinal cord injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1643–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2007.09.001. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Geyh S, Ballert C, Sinnott A,

Charlifue S, Catz A, D’Andrea Greve JM, et al. Quality of life after spinal cord injury: a comparison across six countries. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:322–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.128

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rivers CS, Fallah N, Noonan VK, Whitehurst DG, Schwartz CE, Finkelstein JA, et al. Health conditions: effect on function, health-related quality of

life, and life satisfaction after traumatic spinal cord injury. a prospective observational registry cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:443–51.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.06.012 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Khadije Khazaeli, Effat Hoseini, Amir Hosein Nasir, Mousa Amarloui, Mohammad Kazem Ganji, editor. Relationship

between level of injury and quality of life in spinal cord injury (SCI) patients: Payesh. 2019; 18: 45-51. * Ahmed N, Quadir MM, Rahman MA, Alamgir H. Community integration and life

satisfaction among individuals with spinal cord injury living in the community after receiving institutional care in Bangladesh. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:1033–40.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1283713 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Littooij E, Widdershoven GAM, Stolwijk-Swüste JM, Doodeman S, Leget CJW, Dekker J. Global meaning in people

with spinal cord injury: content and changes. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39:197–205. https://doi.org/10.1179/2045772314Y.0000000290 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tzanos

I-A, Kyriakides A, Gkintoni E, Panagiotopoulos E. Quality of life (QoL) of people with spinal cord injury (SCI) in Western Greece. RS. 2019;4:7 https://doi.org/10.11648/j.rs.20190401.12

Article Google Scholar * Gibbs K, Beaufort A, Stein A, Leung TM, Sison C, Bloom O. Assessment of pain symptoms and quality of life using the International Spinal Cord Injury Data Sets in

persons with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2019;5:13 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0178-8 Article Google Scholar * Siddall PJ, Middleton JW. Spinal cord

injury-induced pain: mechanisms and treatments. Pain Manag. 2015;5:493–507. https://doi.org/10.2217/pmt.15.47 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Finley MA, Euiler E Association of

musculoskeletal pain, fear-avoidance factors, and quality of life in active manual wheelchair users with SCI: a pilot study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2019:1–8.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2019.1565717. * Buzzell A, Chamberlain JD, Schubert M, Mueller G, Berlowitz DJ, Brinkhof MWG Perceived sleep problems after spinal cord injury: Results from

a community-based survey in Switzerland. J Spinal Cord Med. 2020:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2019.1710938. * Bökel A, Egen C, Gutenbrunner C, Weidner N, Moosburger J, Abel F-R, et

al. Querschnittlähmung in Deutschland—eine Befragung zur Lebens- und Versorgungssituation von Menschen mit Querschnittlähmung. [Spinal Cord Injury in Germany—a Survey on the Living and Care

Situation of People with Spinal Cord Injury]. Rehabilitation (Stuttg). 2020;59:205–13. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1071-5935 Article Google Scholar * Cooper RA, Cooper R. Quality-of-life

technology for people with spinal cord injuries. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010;21:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2009.07.004 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Sturm C, Bökel A,

Korallus C, Geng V, Kalke YB, Abel R, et al.. Promoting factors and barriers to participation in working life for people with spinal cord injury. JMET-D-20-00142R1.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-020-00288-7. * Fekete C, Wahrendorf M, Reinhardt JD, Post MWM, Siegrist J. Work stress and quality of life in persons with disabilities from four European

countries: the case of spinal cord injury. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1661–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0610-7 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Geyh S, Kunz S, Müller R, Peter C.

Describing functioning and health after spinal cord injury in the light of psychological-personal factors. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48:219–34. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2027 Article

PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study is based on data from the International Spinal Cord Injury (InSCI) Community Survey, providing the evidence for the

Learning Health System for Spinal Cord Injury (LHS-SCI, see Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2017;96(Suppl): S23–S34). The LHS-SCI is an effort to implement the recommendations described in the WHO

report International Perspectives on Spinal Cord Injury (Bickenbach J et al. Geneva: WHO Press; 2013). The members of the InSCI Steering Committee are: James Middleton (ISCoS representative;

Member Scientific Committee; Australia), Julia Patrick Engkasan (ISPRM representative; Malaysia), Gerold Stucki (Chair Scientific Committee; Switzerland), Mirjam Brach (Representative

Coordinating Institute; Switzerland), Jerome Bickenbach (Member Scientific Committee; Switzerland), Christine Fekete (Member Scientific Committee; Switzerland), Christine Thyrian

(Representative Study Center; Switzerland), Linamara Battistella (Brazil), Jianan Li (China), Brigitte Perrouin-Verbe (France), Christoph Gutenbrunner (Member Scientific Committee; Germany),

Christina-Anastasia Rapidi (Greece), Luh Karunia Wahyuni (Indonesia), Mauro Zampolini (Italy), Eiichi Saitoh (Japan), Bum Suk Lee (Korea), Alvydas Juocevicius (Lithuania), Nazirah Hasnan

(Malaysia), Abderrazak Hajjioui (Morocco), Marcel W.M. Post (Member Scientific Committee; The Netherlands), Johan K. Stanghelle (Norway), Piotr Tederko (Poland), Daiana Popa (Romania),

Conran Joseph (South Africa), Mercè Avellanet (Spain), Michael Baumberger (Switzerland), Apichana Kovindha (Thailand), Reuben Escorpizo (Member Scientific Committee; USA). GerSCI team This

study is a project of several collaborating partners. The cooperating clinics, which are members of the German-speaking Medical Society for Paraplegiology, provided the field access and sent

the questionnaires. The organisation, coordination, data management and descriptive evaluation took place in the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine of Hannover Medical School. The study

was carried out in collaboration with the following specialised SCI-centers: Center of spinal cord injuries and diseases / Department of Paraplegiology and Neuro-Urology, Central Hospital

Bad Berka headed by Dr. med. Ines Kurze, SCI Center Median Clinic Bad Tennstedt headed by Dr. med. Helgrit Marz-Loose, Paraplegic Center of the University and Rehabilitation Clinic Ulm

headed by Dr. med. Yorck-Bernhard Kalke, Medical Rehabilitation Center for Paraplegics of the Heinrich Summer Clinic in Bad Wildbad headed by Dr. med. Michael Zell, Center for Tetra- and

Paraplegia of the Orthopedic Clinic Hessisch Lichtenau headed by Dr. med. Marion Saur, Center for Paraplegics of the Clinic Hohe Warte Bayreuth headed by PD Dr. med. Rainer Abel, Department

of Paraplegics, University Hospital Heidelberg headed by Prof. Dr. med. Nobert Weidner and the Center for Spinal Cord Injuries of the Emergency Hospital Berlin headed by Dr. med. Andreas

Niedeggen. FUNDING The study was funded by Manfred-Sauer-Foundation. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of

Rehabilitation Medicine, Hannover Medical School, Hanover, Germany Christian Sturm, Christoph M. Gutenbrunner, Christoph Egen, Christoph Korallus & Andrea Bökel *

Manfred-Sauer-Foundation, Lobbach, Germany Veronika Geng * Institute for Physiotherapy, University Hospital Jena, Jena, Germany Christina Lemhöfer * RKU – University and Rehabilitation

Clinics Ulm, Ulm, Germany Yorck B. Kalke * Center for spinal injuries, Trauma Hospital Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany Roland Thietje * Treatment Centre for Spinal Cord Injuries, Trauma Hospital

Berlin, Berlin, Germany Thomas Liebscher * SCI Unit, Klinikum Bayreuth GmbH, Bayreuth, Germany Rainer Abel Authors * Christian Sturm View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Christoph M. Gutenbrunner View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Christoph Egen View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Veronika Geng View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Christina Lemhöfer View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yorck B. Kalke View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Christoph

Korallus View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Roland Thietje View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Thomas Liebscher View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Rainer Abel View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Andrea Bökel View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS CS: analysed data and wrote article Andrea Bökel:

led statistics, organized GerSCI. CE: organized GerSCI. CL: helped with data analysis, references and review process. VG: connection to funder of the study and organized parts of the study.

YBK: chief of one of the study centers, organization of recruitment and checked and corrected the article CK: organization of recruitment and checked and corrected the article RT: chief of

one of the study centers, organization of recruitment and checked and corrected the article RA: chief of one of the study centers, organization of recruitment and checked and corrected the

article CMG: head of GerSCI team Hanover, representative for Germany in the International Spinal Cord Injury Survey (InSCI). CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Christian Sturm. ETHICS

DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. STATEMENT OF ETHICS Study was approved by the Ethics committee of the Hannover Medical School (MHH), in

accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (No. 7374), as well as the Commissioner for Data Protection at MHH. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the

source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative

Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by

statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Sturm, C., Gutenbrunner, C.M., Egen, C. _et al._ Which factors have an association

to the Quality of Life (QoL) of people with acquired Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)? A cross-sectional explorative observational study. _Spinal Cord_ 59, 925–932 (2021).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00663-z Download citation * Received: 03 December 2020 * Revised: 24 June 2021 * Accepted: 25 June 2021 * Published: 08 July 2021 * Issue Date: August 2021

* DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00663-z SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link

is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative