- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Antiestrogens (AEs) are widely used for treatment of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα)-positive breast cancer, but display variable degrees of partial agonism in estrogen target tissues

and breast cancer (BC) cells. The fact that BC cells resistant to selective ER modulators (SERMs) like tamoxifen (Tam) can still be sensitive to pure AEs, also called selective ER

downregulators, suggests different mechanisms of action, some of which may contribute to the more complete suppression of estrogen target genes by pure AEs. We report herein that pure AEs

such as fulvestrant induce transient binding of ERα to DNA, followed by rapid release after 30–40 min without loss of nuclear localization. Loss of DNA binding preceded receptor degradation

and was not prevented by proteasome inhibition. Chromatin was less accessible in the presence of fulvestrant than with estradiol or Tam as early as 20 min following treatment, suggesting

that chromatin remodeling by pure AEs at ERα target regions prevents transcription in spite of receptor binding. SUMO2/3 marks were detected on chromatin at the peak of ERα binding in cells

treated with pure AEs, but not SERMs. Furthermore, decreasing SUMOylation by overexpressing the deSUMOylase SENP1 significantly delayed receptor release from DNA and de-repressed expression

of estrogen target genes in the presence of fulvestrant, both in ERα-expressing MCF-7 cells and in transiently transfected ER-negative SK-BR-3 cells. Finally, mutation V534E, identified in a

breast metastasis resistant to hormonal therapies, prevented ERα modification and resulted in increased transcriptional activity of estrogen target genes in the presence of fulvestrant in

SK-BR-3 cells. Together, our results establish a role for SUMOylation in achieving a more complete transcriptional shut-off of estrogen target genes by pure AEs vs. SERMs in BC cells.

SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS CIRCRNA-SFMBT2 ORCHESTRATES ERΑ ACTIVATION TO DRIVE TAMOXIFEN RESISTANCE IN BREAST CANCER CELLS Article Open access 31 July 2023 XAF1 DESTABILIZES

ESTROGEN RECEPTOR Α THROUGH THE ASSEMBLY OF A BRCA1-MEDIATED DESTRUCTION COMPLEX AND PROMOTES ESTROGEN-INDUCED APOPTOSIS Article 16 April 2022 NEDDYLATION NEGATIVELY REGULATES ERRΒ

EXPRESSION TO PROMOTE BREAST CANCER TUMORIGENESIS AND PROGRESSION Article Open access 24 August 2020 INTRODUCTION About 70% of breast tumors are classified as positive for the estrogen

receptor alpha (ERα), a ligand-dependent transcription factor that controls expression of proliferative genes in breast cancer (BC) cells [1]. When bound by estrogens, ERα rapidly binds DNA

at estrogen response elements (EREs) and recruits cofactors with histone-modifying activities, chromatin remodeling complexes, and the basal transcriptional machinery, resulting in altered

expression of target genes [1,2,3]. Antiestrogens (AEs) are small synthetic molecules designed to compete with estrogens and block ERα transcriptional activity [4,5,6,7]. Selective ER

modulators (SERMs) like Tamoxifen (Tam) induce gene- and cell type-specific patterns of cofactor recruitment to ERα, leading to estrogenic effects in tissues such as bone and uterus

[8,9,10,11]. In contrast, fulvestrant was originally described as a “pure” AE as it is antagonistic in these tissues [12, 13]; it is also more efficient than SERMs in suppressing ERα

transcriptional activity in BC cells [14, 15]. The observation that BC cells resistant to SERMs can still be sensitive to pure AEs in experimental models [16,17,18] or in the clinic [19, 20]

implies different mechanisms of action, some of which may contribute to the increased transcriptional inhibition by pure AEs vs. SERMs. Pure AEs are also currently called selective ER

downregulators/degraders (SERDs), as they lead to increased turnover of ERα via the ubiquitin—proteasome pathway [6, 7]. ERα degradation likely contributes to the antiestrogenic profile of

pure AEs, but ERα levels are significantly depleted only after several hours [21,22,23,24], whereas estradiol (E2) or Tam can activate transcription within 1 h [8, 9, 25,26,27]. After 1 h of

fulvestrant treatment in MCF-7 cells, ERα binds to ~ 33% of the regulatory regions bound in the presence of E2 [27], suggesting that transcription of the corresponding genes is prevented

via means other than ERα degradation. In addition, pure AEs remain more efficacious than SERMs at suppressing transcription of estrogen reporter genes in HepG2 cells, a model in which they

do not accelerate ERα turnover [23, 24]. We previously reported that pure AEs can be distinguished from SERMs by their capacity to induce rapid modification of ERα by SUMO1/2/3 in

receptor-positive BC cell lines and in transfected ER-negative cell lines following pure AE treatment [24]. Reporter assays in HepG2 cells showed that abrogating SUMOylation by

overexpression of a deSUMOylase partially de-repressed ERα transcriptional activity in the presence of pure AEs [24]. However, the impact of pure AE-induced SUMOylation on transcriptional

repression of ERα in BC cells remains uncharacterized, and the mechanisms by which SUMOylation may contribute to the differential properties of pure AEs vs. SERMs are currently unclear.

Herein, we investigated the impact of SUMOylation on the kinetics of ERα association with DNA, on chromatin accessibility and on transcriptional suppression, to better understand the role of

this modification in the more complete repression of ERα-mediated transcription in the presence of pure AEs compared with SERMs in BC cells. Our results demonstrate that induction of

SUMOylation by pure AEs contributes to their stronger antiestrogenicity compared with SERMs, and that a naturally occurring mutation that abrogates ERα SUMOylation leads to increased

transcription of estrogen target genes in the presence of fulvestrant in BC cells. RESULTS FULVESTRANT (ICI182,780) AND 4-HYDROXYTAMOXIFEN EXHIBIT DIFFERENTIAL REGULATION OF ESTROGEN TARGET

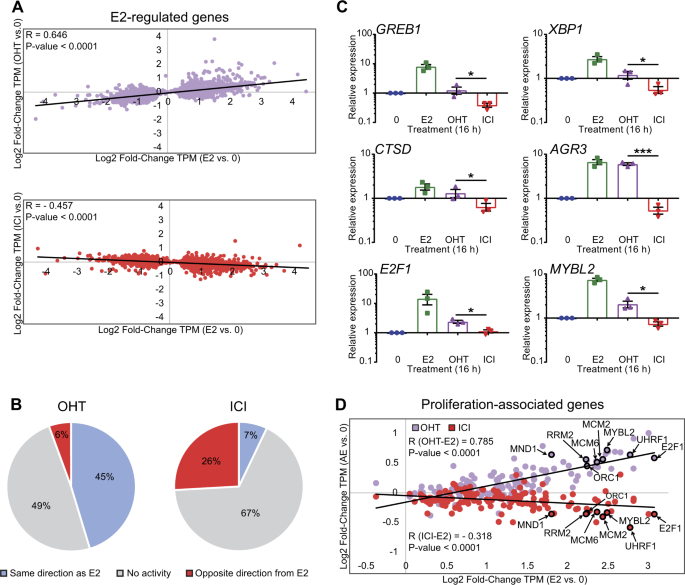

GENES IN MCF-7 CELLS Transcription of estrogen target genes was previously shown by microarray analyses to be repressed more efficiently by the pure AE fulvestrant (ICI182,780) than by

various SERMs in the ERα-positive MCF-7 BC cell line [14, 15]. Here, we have used RNA-sequencing to identify estrogen target genes differentially regulated by ICI182,780 and the active Tam

metabolite, 4-hydroxytamoxifen (OHT), in MCF-7 cells following 16 h of treatment in estrogen-depleted medium. Analysis of transcriptomes from three independent experiments with

Kallisto/Sleuth [28, 29] revealed that E2 regulated a large number of genes (2039 induced and 1878 repressed genes) in a significant manner (_q_ < 0.05) compared with non-treated

controls. Consistent with previous studies performed at different time points [14, 15], a smaller number of genes (82) were significantly regulated by OHT using the same statistical cutoff,

whereas genes significantly regulated by ICI182,780 were rare (12). Using Log2_Fold Change of RNA levels (TPM) in treated vs. vehicle samples as a measure of gene regulation, we observed a

positive correlation between regulations by OHT and E2 in a linear regression analysis (_R_ = 0.646; _P_ value < 0.0001), albeit with much weaker overall regulation by OHT than by E2

(Fig. 1a, top). Conversely, there was an anti-correlation between gene regulations by ICI182,780 and by E2 (_R_ = −0.457; _P_ value < 0.0001) (Fig. 1a, bottom). Overall, most E2 target

genes regulated by OHT were affected in the same direction as E2, and far fewer in the opposite direction (45 and 6%, respectively, Fig. 1b), whereas this proportion was reversed for

ICI182,780 (7 and 26%, respectively, Fig. 1b). In addition, 178 genes were differentially regulated by OHT and ICI182,780 (_q_ < 0.05, Suppl. Table 1). This included well-characterized

direct E2 target genes such as _GREB1_, _XBP1, CTSD_, and _AGR3_, as well as proliferation-associated genes [30] like _E2F1_ and _MYBL2_ (Fig. 1c,d). Consistent with these observations,

MCF-7 cells grew more slowly in the presence of ICI182,780 than OHT (100 nM in estrogen-depleted medium) (Suppl. Figure 1). These results are compatible with previous reports that ICI182,780

blocks MCF-7 cell proliferation with increased efficacy compared with OHT [12], and with the existence of different mechanisms of transcriptional regulation by the two AEs. ERΑ BINDING TO

DNA IS BIPHASIC IN THE PRESENCE OF ICI182,780 Although SERMs and E2 induce binding of ERα to EREs at target gene promoters or enhancers [9, 27], pure AEs were reported to affect binding to

DNA to varying extents in different studies. ERα association to DNA was not detected at the _TFF1/pS2_ promoter after 3 h of treatment with ICI182,780 by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

in MCF-7 cells [26], but binding of ERα at this site and at other EREs was observed after 1 h of ICI182,780 treatment in the same cell line [27]. Here, we performed time course ChIP

experiments in MCF-7 cells to monitor receptor recruitment at EREs upstream of the E2 target genes _TFF1_, _GREB1_, and _CTSD_ in the presence of E2 or ICI182,780 (Fig. 2 and Suppl. Figure

2A). Receptor binding was induced by ICI182,780, with a peak after 30 min of treatment, following kinetics similar to those in the presence of E2. However, binding to DNA in the presence of

ICI182,780 was then lost rapidly between 30 and 60 min, with a gradual return to basal levels (or lower) over the next 3 h (Fig. 2 and Suppl. Figure 2A, magenta vs. blue). Neither E2 nor

ICI182,780 induced receptor recruitment at control regions located in the _GREB1_ and _CTSD_ gene bodies (Suppl. Figure 2B). These results reconcile previous observations [26, 27] and

contrast the impact of ICI182,780 treatment on ERα association to DNA with that of E2. Indeed, increased ERα binding was observed at all time points with E2, although levels of bound

receptor varied over time (Fig. 2 and Suppl. Figure 2A, green vs. blue). These observations, obtained using quantitative real-time PCR, are consistent with the previously described strong

recruitment of ERα to the _TFF1_ and _CTSD_ promoters after 30 min of E2 treatment, followed by decreased association at 1 h observed by semi-quantitative agarose-gel based PCR analysis [8].

However, we did not observe clear cyclical patterns of ERα recruitment to these target elements in the presence of E2 as previously reported [25, 26], and the timing of the initial peak of

ERα association was different from the ones in these studies, but this may be owing to the different experimental conditions (e.g., lack of α-amanitin synchronization in our assays). We

further performed ChIP-Seq analyses of ERα binding to DNA following 30 min or 3 h treatment with E2 or ICI182,780. In the unsupervised PCA analyses of peaks called by model-based analysis of

ChIP-Seq (MACS) using log2-normalized counts (Suppl. Figure 3A, B), samples treated for 30 min by E2 or ICI182,780 clustered separately from non-treated samples, whereas the samples treated

for 180 min were less distinguishable. Differential analysis of peak numbers indicated at the genome-wide scale a significant recruitment of ERα to target chromatin regions after 30 min of

treatment with E2 (32,188 peaks) or ICI182,780 (11,965 peaks) compared with the absence of treatment (3081 peaks, Fig. 3a and Suppl. Table 2). In total, 97% of ICI182,780 peaks overlapped

with E2 peaks at this time point (Fig. 3a). After 3 h of ICI182,780 treatment, however, fewer ERα-binding events were detected (7769 peaks, Fig. 3a and Suppl. Table 2), still essentially

corresponding to peaks observed with E2 at 30 min (97% overlap). These results indicate association of ERα with DNA in the presence of ICI182,780 at a subset of the sites bound in the

presence of E2 at 30 min, with decreased binding at 3 h compared with 30 min (Fig. 3a). Enrichment analysis for known transcription factor motifs returned EREs and FOXA1-binding sites as the

top hits in the presence of E2, consistent with results from previous ERα ChIP-Seq studies [31], as well as in the presence of ICI182,780 (Fig. 3b). This suggests that ERα recruitment at

FOXA1-binding sites is independent of agonist-specific protein–protein interactions engaged by the receptor. ERα peak location analyses also revealed very similar profiles regardless of

treatment conditions (Fig. 3c and Suppl. Figure 3C). Heatmaps of ChIP-Seq binding for ERα in the presence of E2 and ICI182,780 at 30 min at regions containing EREs (3260 peaks) are

consistent with intermediate levels of binding for ICI182,780-treated vs. 0- and E2-treated samples at 30 min, and decreased binding intensity for ICI182,780-treated samples at 3 h vs. 30

min (Suppl. Figure 3D). Notably, ERα-binding events were enriched in the flanking regions (− 25 to + 25 kb from TSS) of E2-regulated genes compared with all other genes in the presence of

ICI182,780 (22% vs. 7%), as well as E2 (37% vs. 13%), and vehicle (7% vs. 2%) (Fig. 3d). When considering a narrower window around the TSS (− 1 to + 1 kb), this enrichment was even more

marked (four- to sixfold, Fig. 3d), compatible with a role for ERα in the transcriptional regulation of neighboring genes. Together, these results confirm that the near absence of partial

agonist activity observed with ICI182,780 compared with E2 (Fig. 1b) does not result from a lack of initial recruitment of ERα to DNA. RAPID LOSS OF BINDING TO DNA PRECEDES LOSS OF ERΑ

PROTEIN AND IS NOT AFFECTED BY PROTEASOME INHIBITION To test whether the loss of DNA binding in the presence of ICI182,780 was due to delocalization of endogenous ERα in MCF-7 cells, as

previously reported for mouse ERα in transfected COS-1 cells [32], we performed immunofluorescence after 30 min, 1 h, and 3 h of ICI182,780 treatment, corresponding to maximal, weak, and no

binding of ERα to DNA, respectively. No significant difference in ERα nuclear localization was observed over this time course of treatment compared with no treatment (Suppl. Figure 4). Thus,

loss of ERα binding to DNA in MCF-7 cells cannot be explained by an increased rate of export from the nucleus in the presence of ICI182,780. Past studies have shown that SERD activity,

associated with pure AEs, leads to increased degradation of ERα via the ubiquitin—proteasome pathway [21, 22, 24, 33]. To compare the kinetics of ERα binding to DNA to those of receptor

degradation, we monitored the steady state levels of ERα in MCF-7 cells at different times after ICI182,780 addition. Concordant with previous results [24, 33], loss of receptor was not

detectable until 60 min of ICI182,780 treatment (total extraction buffer; Fig. 4a, top panel) and increased progressively thereafter, whereas decreased binding to DNA was already observed at

40 min (Fig. 2), suggesting that loss of ERα binding to DNA precedes receptor degradation. To more directly evaluate the impact of ERα degradation on its ability to bind DNA, we pre-treated

MCF-7 cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 2 h, and performed ChIP assays following ICI182,780 treatment for 30 min, 1 h, or 3 h. ERα protein levels were assessed at the same time

points by western analysis of whole cell extracts. MG132 pre-treatment stabilized ERα levels (Fig. 4b, top panel) without affecting kinetics of release of receptor from the _TFF1_ and

_GREB1_ EREs (Fig. 4c), suggesting that the loss of binding to DNA is independent of ERα degradation. SUMO2/3 MARKS COINCIDE WITH ERΑ BINDING TO DNA IN THE PRESENCE OF PURE AES ERα

modification by ubiquitination and SUMOylation is induced by pure AEs/SERDs prior to receptor degradation [22, 24]. Modified forms of ERα were detected at 20 min after ICI182,780 addition,

indicating that these modifications precede loss of receptor binding to DNA. The amount of modified receptor appeared stable at 40 min, then decreased from 60 to 180 min parallel to the loss

of unmodified receptor (Fig. 4a, middle panel). The discrete modified bands observed in the presence of ICI182,780 and the absence of MG132 in MCF-7 cells were previously shown by

immunoprecipitation (IP) with an ERα antibody and blotting with SUMO antibodies to correspond to SUMOylated forms of ERα [24], which, as reported for other proteins [34], represent a small

fraction of total ERα at any given time. Conversely, blotting with an ERα antibody after an IP with a SUMO2/3 antibody led to the detection of both unmodified and modified forms of

endogenous ERα in the ICI182,780-treated, but not the untreated samples (Suppl. Figure 5A). Detection of unmodified ERα may be due to deSUMOylation during the IP procedure, or possibly also

to non-covalent interactions between ERα and SUMO2/3 moieties taking place through putative SUMO-interacting motifs [34]. A more complex ladder of modified ERα forms can be observed both in

the absence and presence of ICI182,780 in MG132-treated MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4b, middle panel), consistent with poly-ubiquitinated forms being present under basal conditions and induced by pure

AEs/SERDs [22, 26]. To investigate the role of SUMOylation in the loss of binding of ERα to DNA, we compared association to DNA of ERα and SUMO2/3 (SUMO2 being the most expressed paralog at

the RNA level in MCF-7 cells, Suppl. Figure 5B), following treatment with the SERM OHT or the pure AEs ICI182,780 or RU58668. ChIP after 30 min of treatment revealed significant binding of

ERα to EREs upstream of _TFF1_, _GREB1_, and _CTSD_ with OHT, ICI182,780, and RU58668 compared with vehicle (Fig. 5a and Suppl. Figure 5C). At the same time, a significant increase in the

SUMO2/3 ChIP signal was only detected for the ICI182,780 and RU58668 conditions at the studied EREs (Fig. 5a and Suppl. Figure 5C), consistent with the detection of modified forms of ERα for

these pure AEs, but not for OHT, by immunoblotting (Fig. 5b). At 3 h of treatment, ERα was bound to DNA in the presence of OHT, but not of the pure AEs (Fig. 5a and Suppl. Figure 5C),

despite reduced but still detectable overall levels of ERα (Fig. 5b). No significant increase in recruitment of SUMO2/3 to DNA was detected either in the presence of OHT or of pure AEs at

this time (Fig. 5a and Suppl. Figure 5C). In contrast with observations at 30 min of ICI182,780 treatment on EREs upstream of _GREB1_ and _CTSD_, association of SUMO2/3 with control regions

in the _GREB1_ and _CTSD_ gene bodies, which do not overlap with EREs, was not increased at the same time point (Suppl. Figure 5D). However, ICI182,780 induced recruitment of SUMO2/3

moieties to several other EREs found within ERα ChIP-Seq peaks in the vicinity of genes regulated by E2 (Suppl. Figure 5E). Thus, SUMO2/3 recruitment as assessed by ChIP at ERα target

regions correlates with the SUMOylation pattern and the ERα DNA-binding profile induced by pure AEs, suggesting that SUMOylated forms of ERα are associated with DNA at early time points. We

next performed ChIP-Seq analyses to map the genome-wide distribution of SUMO2/3 marks following ICI182,780 treatment in MCF-7 cells. In a PCA analysis of peaks called by MACS based on

log2-normalized counts (Suppl. Figure 6A, Supplementary Material and Methods), samples grouped by treatment condition. ICI182,780 treatment for 30 min led to an increase in SUMO2/3 peak

numbers (4507 vs. 3014), followed by a reduction at 3 h (1129 peaks, Fig. 6a and Suppl. Table 2). SUMO2/3 peak location analyses revealed similar profiles in all conditions (Suppl. Figure

6B), with a higher proportion of proximal peaks and fewer gene-associated peaks compared with ERα-binding distributions (Suppl. Figure 3C). Interestingly, whereas CTCF elements remained the

top enriched motif in SUMO2/3 peaks regardless of treatment conditions, EREs figured among the top 10 enriched motifs in peaks observed after ICI182,780 treatment, but not in the vehicle

control (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, several motifs enriched in ERα peaks (e.g.: Jun, AP1, and FOXA2 elements) were also found to be enriched in SUMO2/3 peaks after 30 min of ICI182,780 treatment

(Suppl. Table 3), suggesting an overlap of ERα and SUMO2/3 presence on different DNA motifs. Moreover, pathway enrichment analysis for SUMO2/3 peaks returned estrogen signaling at a much

higher rank in the ICI182,780-treated sample (30 min) than for the control sample (Fig. 6c). Interestingly, the proportion of ERα peaks (detected under both E2 and ICI182,780 treatment for

30 min) overlapping with SUMO2/3 peaks after 30 min of ICI182,780 treatment was highest for the ERα peaks with a strong confidence level (MACS -log10(_q_ value)) (Fig. 6d, e). Indeed, 42.5%

of the Top 5% ERα peaks overlapped with a SUMO2/3 peak in the ICI182,780-treated cells, compared with only 7.69% overlap for all ERα peaks (Fig. 6d, e). This represented a threefold

enrichment compared with overlap with SUMO2/3 peaks in the absence of treatment for the Top 5% ERα peaks, vs. twofold for all ERα peaks (Fig. 6e). A heat map representation of SUMO2/3

binding for the Top 5% ERα peaks indicated an overall increased SUMO2/3 binding in the ICI182,780-treated samples at 30 min compared with control samples and ICI182,780-treated samples at 3

h (Suppl. Figure 6C; note that although regions were selected based on strong ERα binding, correlation between biological replicates for association with SUMO at these peaks was ≥ 0.65

(Spearman) or 0.99 (Pearson) for each treatment, not shown). The regions with highest overall SUMO counts at the top of the graph correspond to regions of higher background also in the input

sequences, and likely reflect regions of focal amplification; these regions were not removed as they also contain detectable ERα and SUMO2/3 peaks. Finally, UCSC browser examination of

several E2 target genes (_TFF1_, _GREB1_, _CTSD_, _CDH26_) confirmed an increased SUMO2/3 ChIP-Seq signal at DNA regions also bound by ERα following 30 min of ICI182,780 treatment (Fig. 6f

and Suppl. Figure 6D), in keeping with observations by ChIP-qPCR (Fig. 5a and Suppl. Figure 5C-E). SUMOYLATION OF ERΑ CONTRIBUTES TO THE RAPID LOSS OF BINDING TO DNA To further investigate

the impact of SUMOylation of ERα on its association with DNA, we generated an MCF-7 cell line stably expressing the deSUMOylase SENP1 from an inducible Tet-ON system. Western analysis of

these cells showed that SENP1 overexpression following a 24 h induction with doxycycline (DOX) resulted in decreased ERα modification levels in cells treated with ICI182,780 for 30 min and 1

h compared with control samples (Fig. 5c). ChIP experiments on EREs upstream of _TFF1_ and _GREB1_ under these conditions revealed that ERα binding to DNA was significantly increased in the

presence of ICI182,780 at 1 h in DOX-treated cells compared with non-induced cells (Fig. 5d). At 3 h, binding levels were similar in both DOX-induced and non-induced samples. Note that ERα

modification levels were similar in the ± DOX conditions at this time by western analysis (Fig. 5c). SUMOylation thus appears to contribute to the rapid loss of ERα binding to DNA.

ICI182,780 INDUCES RAPID CHROMATIN CLOSURE AT ESTROGEN TARGET GENES To investigate the impact of pure AE treatment on chromatin state at ER target regions, we performed formaldehyde-assisted

isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE), which enables isolation of nucleosome-depleted regions permissive to transcription factor and cofactor binding [35]. Following treatment with the

agonist E2, chromatin at EREs located upstream of target genes _TFF1_, _GREB1_, and _CTSD_ was significantly more accessible than in the absence of ligand at 1 h, consistent with recruitment

of ERα and co activators at these sites. OHT did not alter the chromatin state at these EREs compared with the vehicle condition, whereas ICI182,780 treatment markedly decreased

accessibility of these regions at 1 h (Fig. 7a and Suppl. Figures 7A) or 3 h (data not shown) after ligand addition. Strikingly, decreased accessibility was already observed, albeit at a

lower level, 20 min after ICI182,780 addition, before the peak of ERα binding and its subsequent release from DNA. Chromatin accessibility was also decreased at 20 min in control regions in

the _GREB1_ and _CTSD_ gene bodies, although not in a statistically significant manner (Suppl. Figure 7C), possibly reflecting their decreased transcription in the presence of ICI182,780.

Finally, FAIRE-qPCR on additional EREs validated the observed reduction of chromatin accessibility in the presence of ICI182,780 compared with the other treatments (Suppl. Figure 7D). These

results suggest that ICI182,780 induces a progressive chromatin shut-off at promoters and enhancers of E2 target genes, leading to a more complete repression of ERα transcriptional activity

compared with OHT. To test whether SUMOylation plays a role in chromatin closure in the presence of ICI182,780, we performed FAIRE experiments in the Tet-ON SENP1 cell line following 1 h of

treatment. These assays revealed that SENP1 overexpression attenuated chromatin closure in the presence of ICI182,780 at the _TFF1_, _GREB1_, and _CTSD_ EREs compared with untreated controls

or to OHT (Fig. 7b and Suppl. Figure 7B). Together, these results suggest that SUMOylation contributes to the chromatin closure induced by ICI182,780, although other factors, such as

altered cofactor recruitment, may also play a role. As all above-described experiments were performed in estrogen-depleted media, we sought to determine whether the main conclusions were

reproducible in MCF-7 cells grown in complete media containing estrogenic factors, these latter conditions being closer to the tumor environment encountered in the clinic. ChIP-qPCR

confirmed that ERα binding to DNA was significantly increased following 1 h of ICI182,780 treatment compared with vehicle, but not at 3 h (Suppl. Figure 8A). Moreover, chromatin closure at

EREs was also observed after 3 h of ICI182,780 treatment in MCF-7 cells grown in complete media (Suppl. Figure 8B). DOWNREGULATION OF SUMOYLATION ALLEVIATES REPRESSION OF ERΑ TRANSCRIPTIONAL

ACTIVITY BY ICI182,780 To test whether downregulation of SUMOylation in the presence of ICI182,780 leads to an altered regulation of estrogen target gene expression, we treated the MCF-7

Tet-ON SENP1 cells with E2, OHT or ICI182,780 for 8 h and quantified the expression of direct E2 target genes _TFF1_, _GREB1_, _XBP1_, and _CTSD_. Although gene expression levels did not

change in cells overexpressing SENP1 (DOX, magenta) vs. non-induced cells (0, blue) treated with vehicle, E2 or OHT, repression of transcription by ICI182,780 was significantly attenuated

for all tested genes (Fig. 8a). For _TFF1_, _XBP1_, and _CTSD_, mRNA levels in the DOX + ICI182,780-treated cells were similar to those in the vehicle condition, whereas repression of

transcription was only partially relieved in the case of _GREB1_ (Fig. 8a). These results indicate that decreased SUMOylation of ERα reduces the antagonistic potential of ICI182,780. To

confirm these results in another BC cell model, we transiently co-transfected wild-type ERα with GFP-tagged SENP1 or its parental empty vector in the ER-negative SK-BR-3 cells (Fig. 8b).

Treating ERα-transfected cells with E2 led to induction of target genes _TFF1_ and _GREB1_ (Fig. 8c). On both genes, ICI182,780 led to significantly stronger inhibition of gene expression

than OHT (Fig. 8c). However, upon inhibition of ERα SUMOylation by SENP1 overexpression (Fig. 8b), ERα activity in the presence of ICI182,780 was de-repressed and became indistinguishable

from the activity in the presence of OHT (Fig. 8c). Thus, downregulating SUMOylation diminished the antiestrogenic character of ICI182,780 in this cell model as well as in MCF-7 cells.

Because overexpression of SENP1 leads only to partial suppression of SUMOylation (Fig. 5c) and may impact other chromatin-associated proteins than ERα, we sought to use ERα mutants affected

in their capacity to be SUMOylated in the presence of pure AEs. Mutation of several characterized SUMOylation sites in ERα did not abrogate modification in the presence of ICI182,780 [24].

However, in a screen of ERα mutations identified in BC relapses after hormonal therapy, we found that mutation V534E prevented SUMOylation in the presence of pure AEs (El Ezzy et al., in

preparation). Indeed, BRET assays between ERα coupled to _R_lucII and SUMO3 fused to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) in transfected HEK-293 cells revealed a specific interaction between ERα

and SUMO3 in the presence of ICI182,780 only for the wt receptor (Fig. 9a), whereas no SUMOylation of the V534E mutant could be detected in a time course of up to 4 h of treatment (Suppl.

Figure 9). In addition, western analysis did not detect modified forms of the V534E mutant in transfected HEK-293 (not shown) or SK-BR-3 cells (Fig. 9b). Transient transfection of wt or

V534E mutant forms of the receptor in SK-BR-3 cells indicated that, contrary to other mutations associated with resistance to hormonal therapies, e.g., at positions Leu536, Tyr537, and

Asp538 [36,37,38,39], V534E does not lead to constitutive activity of the receptor (Fig. 9c). However, transcriptional activity of this mutant in SK-BR-3 cells was significantly increased

compared with wt ERα in the presence of ICI182,780 for _TFF1_ and _GREB1_ (Fig. 9c). Furthermore, contrary to what was observed with wt ERα, ICI182,780 did not repress transcription of these

genes more efficiently than OHT with the V534E mutant (Fig. 9c). Together, our results indicate that SUMOylation of ERα contributes to its transcriptional repression by pure AEs on

endogenous target genes by inducing rapid loss of receptor binding to response elements at estrogen target genes. DISCUSSION Consistent with prior observations obtained with different

culture conditions, time of exposure to AEs and gene expression profiling platforms [14, 15], our RNA-Seq profiling of ER-positive MCF-7 cells revealed varying degrees of partial agonist

activity of OHT on almost half of E2 targets, whereas ICI182,780 was devoid of activity or opposed E2 effects on nearly all E2-regulated genes. We then explored reported mechanisms of action

specific to pure AEs for their relevance to the increased transcriptional suppression of estrogen target genes in MCF-7 cells. We did not detect differences in nuclear localization of the

endogenous ERα during our experimental time frame in MCF-7 cells. This result contrasts with the observed alteration in nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of mouse ERα in transfected COS-1 cells

[32], but is in agreement with differential extraction experiments in MCF-7 cells [24, 40], and with localization of transfected GFP-tagged ERα in various BC cell lines treated with

ICI182,780 [41, 42]. Our observation of a transient phase of increased association of ERα to EREs between 20 and 40 min of treatment with pure AEs ICI182,780 and RU58668, followed by a

marked loss of association with DNA at longer time points, reconciles previous apparently divergent reports [26, 27]. These results are also compatible with ERα binding to DNA in the

presence of pure AEs in gel shift experiments [43], but suggest progressive exclusion of receptor from chromatin in pure AEs-treated MCF-7 cells. ERα degradation through the

ubiquitin—proteasome pathway, which is induced by AEs with SERD activity, was not responsible for the observed loss of binding to DNA in the presence of ICI182,780, which precedes the

decrease in overall ERα protein levels and happens irrespective of proteasome inhibition. Of note, saturation of the ERα degradation process was also found not to prevent transcriptional

suppression of target gene _TFF1_ by ICI182,780 in MCF-7 cells [44]. Building on our previous report that ERα SUMOylation is induced by pure AEs, but not by the SERM OHT [24], we

investigated the impact of this post-translational modification on the ability of endogenous ERα to bind its target genomic regions and activate gene transcription in the MCF-7 BC cell line.

We show that SUMO2/3 moieties were detected at EREs in the presence of pure AEs, but not OHT. In the absence of a specific antibody recognizing SUMOylated ERα, it is not possible to

conclude that SUMO-modified proteins detected at EREs correspond specifically to modified forms of ERα. Receptor-associated cofactors and histones may be additional modification targets at

ERα-bound DNA sites [45,46,47,48]. However, the SUMO marks detected at EREs disappeared with release of ERα from DNA, even though chromatin remains more closed in the presence of ICI182,780

than in basal conditions, suggesting that these marks are associated with DNA-bound ERα complexes rather than with histones assembled on EREs. The observations that modified ERα was detected

as early as 20 min, i.e., before the peak of binding to DNA, and was found in both the chromatin-bound and the nuclear matrix fractions in MCF-7 cells at 1 h [24], are compatible with

SUMOylated ERα being associated to DNA. SUMOylation of several general TFs or enhancer factors, including nuclear receptors, was previously reported to take place on DNA [49, 50] and to be

associated with transcriptional repression [45, 46, 48, 51,52,53,54,55]. Accordingly, SUMO2/3 ChIP-Seq peaks were enriched in different transcription factor-binding sites, especially CTCF

motifs. However, the enrichment in EREs was stronger after treatment with ICI182,780, consistent with increased SUMOylation of ERα on DNA. Possible reasons for the partial overlap between

ERα peaks and SUMO2/3 peaks could include differences in SUMO2/3 association strength/kinetics at different ERα-bound regions, but also likely the lower number of SUMO2/3 peaks detected (~

4500 SUMO2/3 peaks compared with ~ 12,000 ERα peaks in the presence of ICI182,780 at 30 min). In addition, the median peak height and highest peak for the SUMO2/3 data set (7.4 and 550

reads, respectively) were much lower than those observed for the ERα data set (11.4 and 4400 reads, respectively) in the presence of ICI182,780 (30 min). Finally, the stronger overlap with

SUMO2/3 peaks observed with the top ERα peaks is consistent with the presence of SUMO2/3 marks on only a fraction of ERα bound at a specific site, resulting in better detection at DNA sites

with a more stable association with ERα. SUMO-dependent repression of androgen receptor and glucocorticoid receptor [56, 57] was shown to be mediated by the corepressor DAXX, which

recognizes the modified receptors and, together with HDAC1, HDAC2, DNMT1, and ATRX, induces chromatin closure [58,59,60]. Similarly, we observed that ICI182,780, but not OHT, rapidly

decreased chromatin accessibility at the regulatory regions of E2 target genes, correlating with induction of ERα SUMOylation. Specific corepressors recruited by SUMOylated ERα remain to be

identified, but increased recruitment of the corepressor NCoR by ICI182,780-liganded ERα has been reported [61]. Of interest, SUMOylation of PPARγ and GR was shown to increase recruitment of

NCoR/SMRT [62, 63], and SUMOylation of NCoR itself enhances its activity as a transcriptional repressor [47]. Receptor modification, in addition to altered conformation [64], may also

contribute to the loss of coactivator recruitment [40]. We propose that ERα SUMOylation leads to release of ERα from DNA, either directly, or via the resulting rapid compaction of chromatin

at the regulatory regions of E2 target genes. Parallel increased ubiquitination of ERα (facilitated or not by SUMOylation [65]) would lead to progressive degradation of the receptor in the

nucleus [26, 33] (Fig. 10). Chromatin remodeling at ER target regions coupled with receptor degradation should increase both the efficacy and the duration of the antiestrogenic response,

albeit in a manner that is likely reversible upon cessation of antiestrogenic treatment. In agreement with this model, reducing ERα SUMOylation levels delayed the kinetics of loss of

binding, reduced chromatin closing, and led to a partial de-repression of ERα transcriptional activity on its target genes in the presence of ICI182,780, resulting in similar degrees of

antiestrogenicity for OHT and ICI182,780 in both ER-positive MCF-7 and transfected ER-negative SK-BR-3 cells. In addition, we found that the V534E mutation, characterized in metastatic

tumors progressing after multiple lines of endocrine therapy including SERDs [36], prevents ERα SUMOylation and results in increased transcription of estrogen target genes in the presence of

ICI182,780, without increasing basal activity. It will be interesting in the future to determine whether a specific pattern of mutations is observed after progression on treatment with pure

AEs compared with other forms of hormonal therapies, reflecting the specific mechanisms of action of this class of molecules. Together, our results demonstrate the relevance of SUMOylation

to the suppression of ERα transcriptional activation properties by pure AEs in ER-positive BC cells, and provide a mechanistic framework for these effects via chromatin closure and

suppression of subsequent ERα binding to its target response elements. Future studies will address the identity of cofactors recruited by pure AE-liganded ERα and the connection between

SUMOylation and ubiquitination/degradation of ERα. MATERIALS AND METHODS REAGENTS AND PLASMIDS MG132 (Millipore #474790 (Etobicoke, ON, Canada)), DOX (Sigma D-9891 (Oakville, ON, Canada)),

17β-estradiol (Sigma E2758), (Z)-4-hydroxytamoxifen (ThermoFisher #341210 (Pittsburgh, PA, USA)), ICI182,780 (Abcam ab120131 (Toronto, ON, Canada)) and RU58668 (ThermoFisher #3224) were used

to treat cells. GFP-SENP1 was a gift from Dr. M.J. Matunis (John Hopkins University) and the pSG5-ERα plasmid for wt ERα was from Dr. P. Chambon (Université de Strasbourg). The V534E mutant

was generated by site-directed mutagenesis. YFP-SUMO3 was a gift from Dr. M. Dasso (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). ERα-_R_lucII was generated by PCR amplification of ERα

complementary DNA (cDNA). The PCR product was cloned between the _NheI_ and _BamHI_ restriction sites in the pcDNA3-_R_lucII plasmid (gift from Dr. M. Bouvier, IRIC), in order to fuse

_R_lucII to the C-terminus of ERα. CELL CULTURE Cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination. MCF-7 cells were maintained at 37

°C, 5% CO2 in Alpha MEM (Wisent 310–011 (St-Bruno, QC, Canada)) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma F1051), 1% l-glutamine (Wisent 609–065), and 1% penicillin–streptomycin

(Wisent 450–201). SK-BR-3 and HEK-293 cells were maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) (Wisent 319–005) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1%

penicillin–streptomycin. Three days before experiments, cells were switched to phenol red-free DMEM (Wisent 319–050) containing charcoal-stripped FBS, 2% l-glutamine and 1%

penicillin–streptomycin. CELL TRANSFECTION SK-BR-3 cells were electroporated with 2 µg of ERα expression plasmid and 6 µg of SENP1 expression plasmid per 5 × 106 cells at 240 V and 950 µF

(Gene Pulser® II, Bio-Rad (Mississauga, ON, Canada)). Culture media was changed 24 h post electroporation and cells were treated and collected 48 h post transfection. For BRET experiments,

HEK-293 cells were seeded in 24-well plates (1.5 × 105 cells/well) and co-transfected the next day with a constant amount of plasmid expressing ERα-_R_lucII and increasing amounts of the

YFP-SUMO3 expression vector (ratio 1:5 DNA:polyethylenimine). The following day, HEK-293 cells were treated and processed for BRET assays. RNA EXTRACTION AND RNA-SEQ Cell pellets were lysed

with QIAzol (QIAgen 79306 (Toronto, ON, Canada)) and RNA was extracted per manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were prepared with the KAPA Stranded RNA-Seq Library Preparation Kit (Roche

(Laval, QC, Canada)) and samples were sequenced with the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform (Victoria, BC, Canada). Gene expression was computed with Kallisto [28] with default parameters (100

bootstraps) on the reference genome GRCh38 with the annotation of Ensembl v85 (with cDNA and RNA). Differentially expressed gene analyses were performed with Sleuth, an R package that

implements statistical algorithms (Wald test) for differential analyses that leverage the bootstrap estimates [29]. A Log2 fold-change was calculated from the mean TPM value of each group

for each Kallisto bootstrap and the reported value is the median of all of them. Script is available at https://github.com/maderlab/Oncogene2018-scripts. REVERSE TRANSCRIPTION, QPCR RNA was

reverse transcribed with RevertAid H Minus Reverse Transcriptase (ThermoFisher EP0451). cDNA was quantified by qPCR (Light Cycler 480) with Universal Probe Library (UPL) assays (Suppl. Table

4). Results were analyzed by the ΔΔCt method using two endogenous control genes (_RPLP0_ and _TBP_). For the MCF-7 assays (Fig. 1c), samples were normalized to the “Vehicle” condition. For

the MCF-7 Tet-ON SENP1 assays (Fig. 8a), samples were normalized to the “No DOX, Vehicle” condition. For the SK-BR-3 assays (Figs. 8C and 9C), samples were normalized to the “Empty Vector,

Vehicle” condition. CHIP ChIP was performed as described [66] from MCF-7 cells treated with ERα ligands for various times with the following antibodies: ERα HC-20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology

sc-543 (Dallas, TX, USA)), rabbit IgG (Cedarlane 011-000-003 (Burlington, ON, Canada)), SUMO2/3 (Cedarlane M114-3), or mouse IgG (Cedarlane 015-000-003). The abundance of immunoprecipitated

DNA fragments was quantified by qPCR (Light Cycler 480, Roche) with UPL assays (Roche) (Suppl. Table 5). Results were analyzed by the Percent Input Method. CHIP-SEQ Libraries were prepared

with the KAPA DNA HyperPrep Library Kit (Roche), and samples were sequenced with the Illumina NextSeq500 platform (Flowcell High Output (400 M fragments)—150 cycles paired-end read).

Analyses were performed with a pipeline developed at the McGill University and Génome Québec Innovation Centre (MUGQIC), as part of the GenAP project available at

https://bitbucket.org/mugqic/mugqic_pipelines. WESTERN ANALYSIS Whole cell extracts were prepared as described [24] using a lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 2% sodium dodecyl sulphate, 0.5% Triton, 1% NP40. A total of 30 μg of samples were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (8%

acrylamide). Antibodies ERα 60 C (Millipore 04-820), β-actin (Sigma A5441), SENP1 C-12 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-271360), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit (Cedarlane

111-035-003) and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (Cedarlane 115-035-003) were used. FAIRE FAIRE was performed as described [67] with slight modifications. After extraction, DNA was precipitated

with two volumes of 95% ethanol, 0.3 M sodium acetate pH 5.2 and 20 μg/mL of glycogen (ThermoFisher #R0551) at − 80 °C. Samples were submitted to RNAse A (BioShop #RNA675.100 (Burlington,

ON, Canada)) and proteinase K (ThermoFisher EO0491) digestions (30 min at 37 °C and 1 h at 55 °C, respectively) before reversing crosslink at 65 °C overnight. DNA was purified on EZ-10

columns (BioBasic (Markham, ON, Canada)). The abundance of soluble DNA fragments was quantified by qPCR (Light Cycler 480) with UPL assays (Suppl. Table 5). Results were analyzed by the

Percent Input Method. BRET ASSAYS Cells were detached using phosphate-buffered saline, re-plated in white 96-well plates (ThermoFisher 07-200-628) and supplemented with Coelenterazine H (10

µM, Nanolight Technology (Pinetop, AZ, USA)). Readings were collected using a multidetector plate reader (MITHRAS LB940, Berthold (Bad Wildbad, Germany)) with sequential integration of

signals in the 480 nm and 530 nm windows, for luciferase and YFP light emissions, respectively. The BRET signal (530/480, BRET1) was determined by calculating the ratio of the light

intensity emitted by the YFP fusion over that emitted by the _R_lucII fusion [24]. Values were corrected by subtracting the background BRET1 signal (_R_lucII fusion expressed alone). BRET1

ratios were expressed as a function of the [YFP]/[_R_lucII] expression ratio, estimated by measurement of total fluorescence and luminescence. Total fluorescence was determined with a

microplate reader (FlexStation II, Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, CA, USA)) using an excitation filter at 485 nm and an emission filter at 535 nm. REFERENCES * Flach KD, Zwart W. The first

decade of estrogen receptor cistromics in breast cancer. J Endocrinol. 2016;229:R43–56. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sanchez R, Nguyen D, Rocha W, White JH, Mader S. Diversity in

the mechanisms of gene regulation by estrogen receptors. Bioessays. 2002;24:244–54. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hall JM, McDonnell DP. Coregulators in nuclear estrogen receptor

action: from concept to therapeutic targeting. Mol Interv. 2005;5:343–57. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Ali S, Buluwela L, Coombes RC. Antiestrogens and their therapeutic applications

in breast cancer and other diseases. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:217–32. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Martinkovich S, Shah D, Planey SL, Arnott JA. Selective estrogen receptor

modulators: tissue specificity and clinical utility. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1437–52. PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * McDonnell DP, Wardell SE, Norris JD. Oral selective estrogen

receptor downregulators (SERDs), a beakthrough endocrine therapy for breast cancer. J Med Chem. 2015;58:4883–7. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Traboulsi T, El Ezzy

M, Gleason JL, Mader S. Antiestrogens: structure-activity relationships and use in breast cancer treatment. J Mol Endocrinol. 2017;58:R15–R31. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shang

Y, Hu X, DiRenzo J, Lazar MA, Brown M. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell. 2000;103:843–52. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shang Y,

Brown M. Molecular determinants for the tissue specificity of SERMs. Science. 2002;295:2465–8. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Martin L, Middleton E. Prolonged oestrogenic and

mitogenic activity of tamoxifen in the ovariectomized mouse. J Endocrinol. 1978;78:125–9. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ward RL, Morgan G, Dalley D, Kelly PJ. Tamoxifen reduces

bone turnover and prevents lumbar spine and proximal femoral bone loss in early postmenopausal women. Bone Miner. 1993;22:87–94. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wakeling AE, Dukes M,

Bowler J. A potent specific pure antiestrogen with clinical potential. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3867–73. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gallagher A, Chambers TJ, Tobias JH. The estrogen

antagonist ICI 182,780 reduces cancellous bone volume in female rats. Endocrinology. 1993;133:2787–91. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Frasor J, Stossi F, Danes JM, Komm B, Lyttle

CR, Katzenellenbogen BS. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: discrimination of agonistic versus antagonistic activities by gene expression profiling in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res.

2004;64:1522–33. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wardell SE, Kazmin D, McDonnell DP. Research resource: transcriptional profiling in a cellular model of breast cancer reveals

functional and mechanistic differences between clinically relevant SERM and between SERM/estrogen complexes. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:1235–48. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Hu XF, Veroni M, De Luise M, Wakeling A, Sutherland R, Watts CK, et al. Circumvention of tamoxifen resistance by the pure anti-estrogen ICI 182,780. Int J Cancer. 1993;55:873–6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lykkesfeldt AE, Madsen MW, Briand P. Altered expression of estrogen-regulated genes in a tamoxifen-resistant and ICI 164,384 and ICI 182,780 sensitive

human breast cancer cell line, MCF-7/TAMR-1. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1587–95. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lykkesfeldt AE, Larsen SS, Briand P. Human breast cancer cell lines resistant to

pure anti-estrogens are sensitive to tamoxifen treatment. Int J Cancer. 1995;61:529–34. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Howell A, Robertson JF, Quaresma Albano J, Aschermannova A,

Mauriac L, Kleeberg UR, et al. Fulvestrant, formerly ICI 182,780, is as effective as anastrozole in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer progressing after prior endocrine

treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3396–403. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Osborne CK, Pippen J, Jones SE, Parker LM, Ellis M, Come S, et al. Double-blind, randomized trial comparing

the efficacy and tolerability of fulvestrant versus anastrozole in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer progressing on prior endocrine therapy: results of a North American

trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3386–95. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * El Khissiin A, Leclercq G. Implication of proteasome in estrogen receptor degradation. FEBS Lett.

1999;448:160–6. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wijayaratne AL, McDonnell DP. The human estrogen receptor-alpha is a ubiquitinated protein whose stability is affected differentially

by agonists, antagonists, and selective estrogen receptor modulators. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35684–92. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lupien M, Jeyakumar M, Hebert E, Hilmi K,

Cotnoir-White D, Loch C, et al. Raloxifene and ICI182,780 increase estrogen receptor-alpha association with a nuclear compartment via overlapping sets of hydrophobic amino acids in

activation function 2 helix 12. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:797–816. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hilmi K, Hussein N, Mendoza-Sanchez R, El-Ezzy M, Ismail H, Durette C, et al. Role of

SUMOylation in full antiestrogenicity. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:3823–37. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Metivier R, Penot G, Hubner MR, Reid G, Brand H, Kos M, et al.

Estrogen receptor-alpha directs ordered, cyclical, and combinatorial recruitment of cofactors on a natural target promoter. Cell. 2003;115:751–63. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Reid G, Hubner MR, Metivier R, Brand H, Denger S, Manu D, et al. Cyclic, proteasome-mediated turnover of unliganded and liganded ERalpha on responsive promoters is an integral feature of

estrogen signaling. Mol Cell. 2003;11:695–707. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Welboren WJ, van Driel MA, Janssen-Megens EM, van Heeringen SJ, Sweep FC, Span PN, et al. ChIP-Seq of

ERalpha and RNA polymerase II defines genes differentially responding to ligands. EMBO J. 2009;28:1418–28. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bray NL, Pimentel H,

Melsted P, Pachter L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:525–7. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pimentel H, Bray NL, Puente S, Melsted P,

Pachter L. Differential analysis of RNA-seq incorporating quantification uncertainty. Nat Methods. 2017;14:687–90. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lemieux S, Sargeant T, Laperriere

D, Ismail H, Boucher G, Rozendaal M. et al. MiSTIC, an integrated platform for the analysis of heterogeneity in large tumour transcriptome datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e122 Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hurtado A, Holmes KA, Ross-Innes CS, Schmidt D, Carroll JS. FOXA1 is a key determinant of estrogen receptor function and endocrine response.

Nat Genet. 2011;43:27–33. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dauvois S, White R, Parker MG. The antiestrogen ICI 182780 disrupts estrogen receptor nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. J Cell

Sci. 1993;106:1377–88. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Stenoien DL, Patel K, Mancini MG, Dutertre M, Smith CL, O’Malley BW, et al. FRAP reveals that mobility of oestrogen receptor-alpha is

ligand- and proteasome-dependent. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:15–23. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Geiss-Friedlander R, Melchior F. Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 2007;8:947–56. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Simon JM, Giresi PG, Davis IJ, Lieb JD. Using formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements (FAIRE) to isolate active

regulatory DNA. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:256–67. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Toy W, Shen Y, Won H, Green B, Sakr RA, Will M, et al. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations

in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1439–45. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Robinson DR, Wu YM, Vats P, Su F, Lonigro RJ, Cao X, et al.

Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1446–51. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Harrod A, Fulton J, Nguyen VTM,

Periyasamy M, Ramos-Garcia L, Lai CF, et al. Genomic modelling of the ESR1 Y537S mutation for evaluating function and new therapeutic approaches for metastatic breast cancer. Oncogene.

2017;36:2286–96. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Angus L, Beije N, Jager A, Martens JW, Sleijfer S. ESR1 mutations: Moving towards guiding treatment decision-making in metastatic

breast cancer patients. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;52:33–40. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Stenoien DL, Mancini MG, Patel K, Allegretto EA, Smith CL, Mancini MA. Subnuclear trafficking

of estrogen receptor-alpha and steroid receptor coactivator-1. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:518–34. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Htun H, Holth LT, Walker D, Davie JR, Hager GL. Direct

visualization of the human estrogen receptor alpha reveals a role for ligand in the nuclear distribution of the receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:471–86. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Gushima M, Kawate H, Ohnaka K, Nomura M, Takayanagi R. Raloxifene induces nucleolar translocation of the estrogen receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;319:14–22. Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Metzger D, Berry M, Ali S, Chambon P. Effect of antagonists on DNA binding properties of the human estrogen receptor in vitro and in vivo. Mol Endocrinol.

1995;9:579–91. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wardell SE, Marks JR, McDonnell DP. The turnover of estrogen receptor alpha by the selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD) fulvestrant is a

saturable process that is not required for antagonist efficacy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:122–30. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Shiio Y, Eisenman RN. Histone

sumoylation is associated with transcriptional repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13225–30. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nathan D, Ingvarsdottir K, Sterner DE, Bylebyl

GR, Dokmanovic M, Dorsey JA, et al. Histone sumoylation is a negative regulator in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and shows dynamic interplay with positive-acting histone modifications. Genes Dev.

2006;20:966–76. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tiefenbach J, Novac N, Ducasse M, Eck M, Melchior F, Heinzel T. SUMOylation of the corepressor N-CoR modulates its

capacity to repress transcription. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1643–51. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Garcia-Dominguez M, Reyes JC. SUMO association with repressor

complexes, emerging routes for transcriptional control. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:451–9. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Neyret-Kahn H, Benhamed M, Ye T, Le Gras S, Cossec JC,

Lapaquette P, et al. Sumoylation at chromatin governs coordinated repression of a transcriptional program essential for cell growth and proliferation. Genome Res. 2013;23:1563–79. Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Paakinaho V, Kaikkonen S, Makkonen H, Benes V, Palvimo JJ. SUMOylation regulates the chromatin occupancy and anti-proliferative gene programs

of glucocorticoid receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:1575–92. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Seeler JS, Dejean A. Nuclear and unclear functions of SUMO. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

2003;4:690–9. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shin JA, Choi ES, Kim HS, Ho JC, Watts FZ, Park SD, et al. SUMO modification is involved in the maintenance of heterochromatin stability

in fission yeast. Mol Cell. 2005;19:817–28. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Uchimura Y, Ichimura T, Uwada J, Tachibana T, Sugahara S, Nakao M, et al. Involvement of SUMO

modification in MBD1- and MCAF1-mediated heterochromatin formation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23180–90. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Stielow B, Sapetschnig A, Wink C, Kruger I, Suske

G. SUMO-modified Sp3 represses transcription by provoking local heterochromatic gene silencing. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:899–906. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Maison C,

Quivy JP, Almouzni G. Suv39h1 links the SUMO pathway to constitutive heterochromatin. Mol Cell Oncol. 2016;3:e1225546 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Poukka H, Karvonen U,

Janne OA, Palvimo JJ. Covalent modification of the androgen receptor by small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (SUMO-1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14145–50. Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Tian S, Poukka H, Palvimo JJ, Janne OA. Small ubiquitin-related modifier-1 (SUMO-1) modification of the glucocorticoid receptor. Biochem J. 2002;367(Pt 3):907–11. Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lin DY, Fang HI, Ma AH, Huang YS, Pu YS, Jenster G, et al. Negative modulation of androgen receptor transcriptional activity by Daxx. Mol Cell Biol.

2004;24:10529–41. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lin DY, Huang YS, Jeng JC, Kuo HY, Chang CC, Chao TT, et al. Role of SUMO-interacting motif in Daxx SUMO

modification, subnuclear localization, and repression of sumoylated transcription factors. Mol Cell. 2006;24:341–54. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shih HM, Chang CC, Kuo HY, Lin

DY. Daxx mediates SUMO-dependent transcriptional control and subnuclear compartmentalization. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1397–400. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Webb P, Nguyen P,

Kushner PJ. Differential SERM effects on corepressor binding dictate ERalpha activity in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6912–20. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pourcet B, Pineda-Torra

I, Derudas B, Staels B, Glineur C. SUMOylation of human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha inhibits its trans-activity through the recruitment of the nuclear corepressor NCoR.

J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5983–92. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hua G, Ganti KP, Chambon P. Glucocorticoid-induced tethered transrepression requires SUMOylation of GR and formation of

a SUMO-SMRT/NCoR1-HDAC3 repressing complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E635–43. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pike AC, Brzozowski AM, Walton J, Hubbard RE, Thorsell AG, Li

YL, et al. Structural insights into the mode of action of a pure antiestrogen. Structure. 2001;9:145–53. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Heideker J, Perry JJ, Boddy MN. Genome

stability roles of SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases. DNA Repair. 2009;8:517–24. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rahman S, Zorca CE, Traboulsi T, Noutahi E, Krause MR,

Mader S, et al. Single-cell profiling reveals that eRNA accumulation at enhancer-promoter loops is not required to sustain transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:3017–30. Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Eeckhoute J, Lupien M, Meyer CA, Verzi MP, Shivdasani RA, Liu XS, et al. Cell-type selective chromatin remodeling defines the active subset of FOXA1-bound

enhancers. Genome Res. 2009;19:372–80. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Christian Charbonneau for his assistance with the

microscope imaging, and Florent Guilloteau and Jennifer Huber from the IRIC Genomics Core Facility for their work on the RNA-Seq and ChIP-Seq experiments, respectively. We thank Dr. John H

White for critical reading of the manuscript. FUNDING This work has been funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant 125863 to SM) and from the Canadian Imperial Bank of

Commerce (CIBC) breast cancer research chair at Université de Montréal (to SM). TT was the recipient of a _Fonds de recherche Québec—santé_ (FRQS) scholarship and both TT and MEE were

recipients of several scholarships from the Université de Montréal. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Institute for Research in Immunology and Cancer, Montréal, QC, H3C 3J7,

Canada Tatiana Traboulsi, Mohamed El Ezzy, Vanessa Dumeaux, Eric Audemard & Sylvie Mader * Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine, Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC, H3C

3J7, Canada Tatiana Traboulsi & Sylvie Mader * PERFORM Centre, Concordia University, Montréal, QC, H4B 1R6, Canada Vanessa Dumeaux Authors * Tatiana Traboulsi View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mohamed El Ezzy View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Vanessa Dumeaux View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Eric Audemard View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sylvie

Mader View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS TT and SM designed the project. TT performed all the experimental work, except for

the BRET assays, which were done by MEE. VD and EA performed bio-informatics analyses for the RNA-Seq and ChIP-Seq data sets. TT and SM analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript, with

input from VD. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Sylvie Mader. ETHICS DECLARATIONS CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. ELECTRONIC

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS AND METHODS, REFERENCES AND FIGURE LEGENDS SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURES SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 1 SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES 2–5 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN

ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format,

as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third

party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright

holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Traboulsi, T., El Ezzy, M., Dumeaux,

V. _et al._ Role of SUMOylation in differential ERα transcriptional repression by tamoxifen and fulvestrant in breast cancer cells. _Oncogene_ 38, 1019–1037 (2019).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-018-0468-9 Download citation * Received: 26 June 2017 * Revised: 15 July 2018 * Accepted: 20 July 2018 * Published: 06 September 2018 * Issue Date: 14 February

2019 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-018-0468-9 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable

link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative