- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

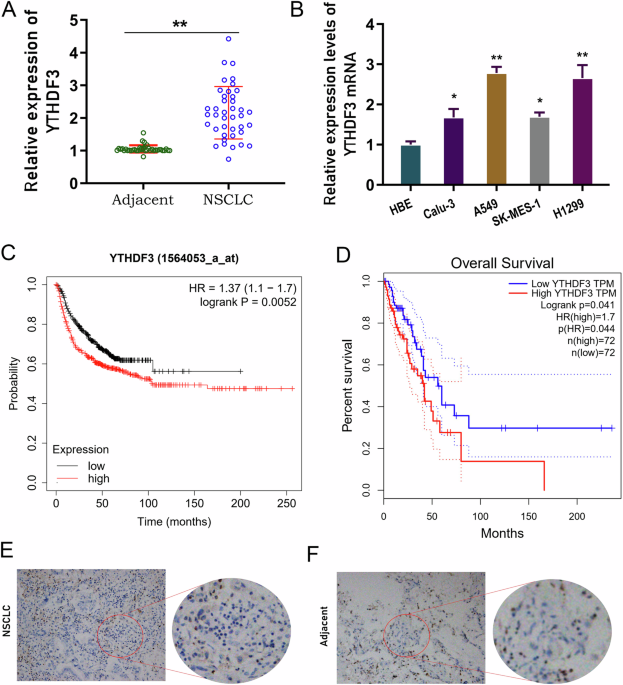

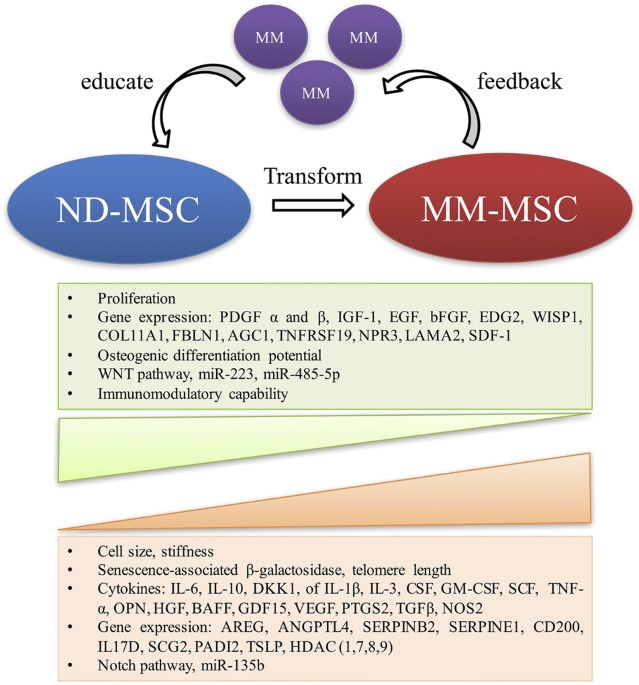

ABSTRACT Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma cell (PC) disorder, characterized by a complex interactive network of tumour cells and the bone marrow (BM) stromal microenvironment,

contributing to MM cell survival, proliferation and chemoresistance. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) represent the predominant stem cell population of the bone marrow stroma, capable of

differentiating into multiple cell lineages, including fibroblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes and osteoblasts. MSCs can migrate towards primary tumours and metastatic sites, implying that

these cells might modulate tumour growth and metastasis. However, this issue remains controversial and is not well understood. Interestingly, several recent studies have shown functional

abnormalities of MM patient-derived MSCs indicating that MSCs are not just by-standers in the BM microenvironment but rather active players in the pathophysiology of this disease. It appears

that the complex interaction of MSCs and MM cells is critical for MM development and disease outcome. This review will focus on the current understanding of the biological role of MSCs in

MM as well as the potential utility of MSC-based therapies in this malignancy. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS CXCL12/CXCR4 AXIS SUPPORTS MITOCHONDRIAL TRAFFICKING IN TUMOR MYELOMA

MICROENVIRONMENT Article Open access 21 January 2022 HIGH LEVEL OF CIRCULATING CELL-FREE TUMOR DNA AT DIAGNOSIS CORRELATES WITH DISEASE SPREADING AND DEFINES MULTIPLE MYELOMA PATIENTS WITH

POOR PROGNOSIS Article Open access 28 November 2024 BMI1 REGULATES MULTIPLE MYELOMA-ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGE’S PRO-MYELOMA FUNCTIONS Article Open access 15 May 2021 INTRODUCTION Multiple

myeloma (MM) is a haematological malignancy characterized by a clonal proliferation of plasma cells in the bone marrow (BM) and the presence of monoclonal immunoglobulin in the blood and/or

urine. A major characteristic of this disease is the predominant localization of MM cells in the BM. The crosstalk between BM stromal cells and MM cells supports the proliferation, survival,

migration and drug resistance of MM cells, as well as osteoclastogenesis and angiogenesis. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are self-renewing and multipotent progenitors that can differentiate

into a variety of cell types, such as adipocytes, endothelial cells, osteoblasts and fibroblasts, which constitute the main cellular compartment of BM stroma. Many studies have demonstrated

that MSCs play an important role in the growth of different tumour types. As the precursors of BM stromal cells, MSCs are thought to be involved in the pathophysiology and progression of MM

as well. Moreover, MM patient-derived MSCs (MM-hMSCs) seem to be genetically and functionally different compared to MSCs derived from normal donors (ND-hMSCs). Currently, there is

increasing interest in using MSCs for therapeutic applications in cancer patients. In particular, clinical trials have been initiated to evaluate the clinical potential of donor-derived MSCs

to control steroid-resistant graft versus host disease after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation and to support HSC engraftment after both autologous and allogeneic

transplantation in patients with various haematological malignancies, including MM. Here, we review the current understanding of the possible role of MSCs, both in the biology and the

treatment of MM. ABNORMALITIES OF MSCS IN MM MSCs are an essential cell type in the formation and function of the BM microenvironment, and several previous studies have evaluated the

difference between MM-hMSCs and ND-hMSCs. Regardless of the disease stage, the surface immunophenotype of MM-MSCs was similar to that from ND-MSCs [1,2,3,4]. Garderet el al. [3] reported

that MM-MSCs exhibited a much lower proliferative capacity than ND-MSCs, associated with a reduced expression of the receptors for platelet-derived growth factor-α and -β, insulin-like

growth factor-1, epidermal growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). The growth impairment was more pronounced in MM patients with advanced disease and bone lesions [5]. In

contrast, Corre et al. [2] showed that the expansion of BM MSCs was not different among normal donors, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) patients and MM patients.

Compared with their normal counterparts, MM-MSCs differ in their spontaneous and myeloma cell-induced production of cytokines. MM-MSCs can express abnormally high mRNA and protein levels of

interleukin (IL)-6, which is the most potent growth factor involved in MM progression [1,2,3,4]. Dickkopf-1 (DKK1) production was also found to be enhanced in MM-MSCs [2, 3]. In addition,

MM-MSCs can constitutively express high amounts of IL-1β, IL-3, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (CSF), granulocyte monocyte (GM)-CSF, stem cell factor and tumour necrosis factor

(TNF)-α [1,2,3,4]. Zdzisinska et al. [5] observed that MM-MSCs had a higher capacity to produce IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, osteopontin and especially hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and B

cell-activating factor than ND-MSCs in the presence of RPMI 8226 MM cells (under cell-to-cell contact as well as non-contact conditions). The authors of this study also found that MM-MSCs

significantly enhanced the production of sIL-6R by the RPMI 8226 MM cells [5]. In addition, Corre et al. [2] observed that MSCs from MM patients overexpressed growth differentiation factor

15 (GDF15) [2]. Recent studies suggested that GDF15 contributes to myeloma cell growth and chemoresistance and, even more importantly, that high levels of GDF15 are correlated with a poor

prognosis in MM patients [6]. André et al. [7] demonstrated that MM BM-derived MSCs exhibited an increased expression of senescence-associated β-galactosidase, increased cell size, reduced

proliferative capacity and characteristic expression of senescence-associated secretory profile members compared to the normal counterparts. This senescent state most likely participates in

disease progression and relapse by altering the tumour microenvironment [7]. Why do MSCs from MM patients express abnormal cytokines favouring MM progression? Using microarray analysis,

Corre et al. [2] have observed a distinctive gene expression profile between MM-MSCs and ND-MSCs, with differential expression of genes coding for growth and angiogenic factors, as well as

for factors related to bone differentiation. All of these differences were detected after isolation and expansion of MSCs in culture. Garayo et al. [8] observed that cultured MM-MSCs show a

distinctive array-comparative genomic hybridization profile compared to that observed in their normal counterparts. However, to which extent these molecular aberrations in MM-MSCs may have

an impact on their function and, thus, on the progression/relapse of MM disease still remains to be determined [8]. McNee et al. [9] recently identified that peptidyl arginine deiminase 2

(PADI2) was one of the most highly upregulated transcripts, in MSCs from both MGUS and MM patients, that could induce upregulation of IL-6 through its enzymatic deimination of histone H3

arginine 26. Li et al. [10] also found that MM-MSCs had a significantly longer telomere length, which was positively associated with the expression of IL-6 and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3

(CCL3). Some evidence also suggested that the abnormalities of MM-MSCs could be acquired through exposure to myeloma cells. MM cells could reduce the expression of miR-223 and miR-485-5p in

vitro, which altered the senescence phenotype of MM-MSCs with participation of the delta-like homologue 1- iodothyronine deiodinase 3 (DLK1-DIO3) genomic region [11]. Co-cultivation of MM

cells and MM-MSCs induced a reduced miR-223 expression and activation of Notch signalling in MM-MSCs, leading to increased vascular endothelial growth factor and IL-6 expression and impaired

osteogenic differentiation potential [12]. Our group uncovered that MM-hMSCs have a different microRNA (miRNA) expression profile compared to their normal counterparts. Using bioinformatics

tools, we found that some differentially expressed miRNAs were possibly relevant to some functional abnormalities of MM-hMSCs, for example, the impaired osteogenic differentiation [13]. We

also observed that MM cell-derived soluble factors could induce an upregulation of miR-135b expression in ND-hMSCs in an indirect coculture system. Targeting these miRNAs might help in

correcting the MM tumour microenvironment. In addition, Todoerti et al. [14] further determined that BM-MSCs compared to osteoblasts had distinct transcriptional profiles in multiple myeloma

bone disease. Wang et al. [15] demonstrated that the mRNA and protein levels of angiogenic factors were elevated in MSCs derived from multiple myeloma compared with normal donors. Li et al.

[16] also reported that MSCs from MM patients showed impaired immunoinhibitory capability on T cells. André et al. [17] demonstrated that altered immunomodulation capacities of MM BM-MSCs

were linked to variations in their immunogenicity and secretion profile including IL-6, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and CD40. These alterations lead not only to a reduced

inhibition of T-cell proliferation but also to a shift in the T helper 17 cell/ regulatory T-cell balance [17]. Furthermore, Pevsner-Fischer et al. [18] recently observed that MM-hMSCs

exhibited a different expression of extracellular-regulated kinase-1/2 phosphorylation in response to Toll-like receptor ligands and epidermal growth factor compared with ND-hMSCs. Evidence

also showed that MM-MSCs, in contrast to ND-MSCs, could produce a higher amount of immune-modulatory factors that are involved in granulocytic-myeloid-derived suppressor cell (G-MDSC)

induction. MM-MSCs stimulate G-MDSCs to upregulate immune-suppressive, angiogenesis and inflammatory factors as well as to digest bone matrix [19]. Previous studies also indicated that

MM-MSCs demonstrated other abnormalities, including distinct histone deacetylase (HDAC) expression patterns [20], upregulated thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression and induction of T

helper 2 cell responses [21], a constitutively high level of phosphorylated Myosin II conferring enhanced collagen matrix remodelling and promoting the MM and MSC interaction [22], and a

stiffer phenotype (biomechanical changes) induced by MM cells [23]. All of the data summarized above demonstrate that MM-MSCs are genetically and functionally different from MSCs in healthy

subjects (Fig. 1). All of these MM-MSC abnormalities, either intrinsic or inducible, lead to the formation of a more favourable BM microenvironment for MM tumour development and progression.

EFFECTS OF MSCS ON TUMOUR GROWTH IN MM Stephen Paget proposed the ‘‘seed and soil’’ hypothesis in 1889, indicating that the establishment of tumour metastatic sites is influenced by

cross-interaction between selected cancer cells (‘‘seed’’) and specific organ microenvironments (‘‘soil’’). With regard to MM, tumour cells grow predominantly in BM and the cellular and

non-cellular components of the MM BM microenvironment play an essential role in supporting MM cell proliferation, survival, migration and chemoresistance [24]. Evidence has been provided

that MSCs give rise to most BM stromal cells that interact with MM cells, and are involved in the pathophysiology of MM (Fig. 2). Some studies have shown that interactions between MSCs and

MM cells support the proliferation of myeloma. MSCs strongly support MM cell growth by the production of high levels of IL-6, a major MM cell growth factor [25]. MM cells secrete DKK1, which

prevents MSCs from differentiating into osteoblasts, and the undifferentiated MSCs can produce IL-6, which in turn stimulates the proliferation of DKK1-secreting MM cells [26]. It has been

assumed that direct contact between the two types of cells, partially mediated through the very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) and RGD-peptide mechanisms, was necessary for this induction [25]. In

another study, it was found that a significant increase in IL-6 concentration occurred when the myeloma cells were cocultured with BM MSCs of MM patients in a non-contact Transwell system.

It was suggested that bFGF, secreted by myeloma cells, bound to bFGF receptors on BM MSCs and thus stimulated IL-6 production [27]. Recent evidence showed that survivin was involved in an

anti-apoptotic effect of MSCs on myeloma cells [28]. Direct contact with MSCs was also found to influence MM cell growth and the MM cell phenotype [29]. Furthermore, the crosstalk between BM

MSC and MM cells was reported to support osteoclastogenesis and angiogenesis in MM [30,31,32]. In our study, we found that MSCs had tropism towards MM cells, and CCL25 was identified as a

major MM cell-produced chemoattractant. MSCs favoured the proliferation of MM cells and protected them against spontaneous and Bortezomib-induced apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Infusion of

in vitro expanded murine MSCs in 5T33 MM mice resulted in a significantly shorter survival [33]. Kim et al. [34] also reported that MM cells, U266 and NCI-H929, exhibited an increased

proliferation and a decreased apoptosis rate in the presence of MSCs, which was consistent with our in vitro findings. Noll et al. [35] showed that MSCs derived from bone marrow in myeloma

patients, expressed higher levels of the plasma cell-activating factor IL-6 and the osteoclast-activating factor receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) [35]. Dotterweich et

al. [36] demonstrated that MSC contact promoted angiogenic factor CCN family member 1 (CCN1) splicing and transcription in MM cells, which favoured tumour viability and myeloma bone disease.

Roccaro et al. [37] recently described a mechanism whereby MM-derived BM-MSCs contributed to MM disease progression in vitro and in vivo via released exosomes. Our group also reported that

MM cells can transfer miR146a through exosomes and promote the increase in cytokine secretion in MSCs, which in turn favoured MM cell growth and migration [38]. Moreover, the Bruton tyrosine

kinase (BTK) signal pathway and Connexin-43 were also involved in the MSC and MM cell interaction, which increased myeloma stemness and tumour cell proliferation [39, 40]. However, some

studies described opposite findings. Using a SCID-rab MM mouse model, Li et al. [41, 42] demonstrated that both MSCs and placenta-derived adherent cells, which are mesenchymal-like stem

cells isolated from postpartum human placenta, effectively suppress bone destruction and tumour growth in vivo, although these stem cells significantly support MM cell growth in vitro [41,

42]. Ciavarella et al. [43] also found that, in contrast to BM-derived MSCs, adipose tissue-derived MSCs and umbilical cord-derived MSCs (UC-MSCs) significantly inhibited MM cell

clonogenicity and growth in vitro and in vivo. They proposed that UC-MSCs have a distinct molecular profile compared with other MSCs and exhibit a different effect on MM cells [43]. Atsuta

et al. [44] demonstrated that Fas/Fas-L-induced MM apoptosis played a crucial role in the MSC-based inhibition of MM growth [44]. In addition, there are also some reports showing that MSCs

have no significant effect on MM growth [45,46,47]. Potential explanations were reported regarding the different effects of MSCs on MM tumour growth. Kanehira et al. [48] explored the role

of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) signalling in cellular events where MSCs were converted into either MM-supportive or MM-suppressive stroma. They found that myeloma cells stimulate MSCs to

produce autotaxin, an essential enzyme for the biosynthesis of LPA. LPA receptor 1 (LPA1) and 3 (LPA3) transduce opposite signals to MSCs to determine the fate of MSCs. LPA1-silenced MSCs

showed a delayed progression of MM and tumour-related angiogenesis in vivo, while LPA3-silenced MSCs significantly promoted the progression of MM and tumour-related angiogenesis in vivo.

Therefore, during the different stages and conditions, MSCs might exhibit different effects on MM growth [48]. In addition, it can be assumed that several factors such as the nature of the

in vivo MM model (severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) or non-SCID mice), the MM cell lines used as well as the number and source of the injected MSCs and the timing of injection might

all account for the discrepancy between these studies. The details of the different observations about MSC effect on MM growth are listed in Table 1. ROLE OF MSCS IN BONE DISEASE MM is the

disease with the highest incidence of bone involvement among all the malignant diseases. Abnormalities in conventional radiography can be found in approximately 80% of patients with newly

diagnosed MM. Bone disease in MM is characterized by lytic bone lesions, which can cause severe bone pain, pathologic fractures and hypercalcaemia. The basic mechanism of increased bone

resorption in MM is an uncoupling of normal bone remodelling with increased osteoclast activity and decreased osteoblast function [26]. In MM patients, increased numbers of osteoclasts are

present at sites of bone destruction. These osteoclasts are stimulated by local osteoclast-activating factors that are produced by myeloma cells and/or cells of the bone microenvironment.

The RANK/RANKL/osteoprotegerin (OPG) system has been widely studied in bone remodelling. It has been demonstrated that in MM an increased RANKL/OPG ratio results in enhanced osteoclast

formation and activation, which is a major mechanism in MM-related bone disease [49]. Several other factors have also been identified as main osteoclast inducers in MM: the chemokines CCL3

and CCL4, stromal-derived factor-1α, soluble decoy receptor 3 (DcR3), matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-13, IL-1, IL-3, IL-6 and IL-17 [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65].

Moreover, adhesive interactions between MM and stromal cells also play a significant role in promoting osteoclastogenesis and augmenting the bone destructive process [66]. In addition,

myeloma cells can adhere directly to osteoclasts, resulting in increased myeloma cell proliferation and osteoclastic differentiation [67, 68]. The mechanisms that have been described to be

involved in MM bone disease are listed in Table 2. In addition to the well-established role of osteoclast activation, it is now accepted that a markedly suppressed osteoblast activity

contributes to the development of myeloma bone disease as well. Histomorphometric analysis of bone biopsies from patients with overt myeloma showed a reduced number of osteoblasts on bone

surfaces adjacent to myeloma cells. As the progenitor cells of osteoblasts, MSCs from MM patients (but not MGUS patients) exhibited a significantly decreased osteogenic differentiation

potential compared to MSCs from normal donors [69]. The suppression of osteogenic differentiation of MSCs in MM results from soluble factors produced by MM cells, which influence

osteogenesis-related transcription factors and signalling pathways in MM-hMSCs (Table 2). The communication between MM cells and MSCs also involves cell-to-cell interactions through VLA-4 on

MM cells and VCAM-1 on MSCs, as demonstrated by the capacity of a neutralizing anti–VLA-4 antibody to reduce the inhibitory effects of MM cells on Runx2 activity [70]. The involvement of

the VLA-4/VCAM-1 interaction in the development of bone lesions of MM has recently also been demonstrated using in vivo mouse models [71]. In addition to VLA-4/VCAM-1, other adhesion

molecules appear to be involved in the inhibition of osteoblastogenesis by human MM cells, such as the neural cell adhesion molecule [72]. Wnt signalling has been found to play a critical

role in the regulation of MSC osteoblastogenesis. There are two classes of extracellular antagonists of the Wnt signalling pathway, with distinct inhibitory mechanisms, acting either by

binding directly to Wnt, such as secreted frizzled-related protein (sFRPs) and Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (WIF-1), or by binding to a part of the Wnt receptor complex, including certain members

of the Dickkopf family. The involvement of Wnt signalling inhibitors in the suppression of osteoblast formation and function in MM has been investigated. Increasing Wnt signalling in the

bone microenvironment in multiple myeloma with anti-DKK1 antibody or inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) with lithium chloride resulted in the inhibition of myeloma bone

disease as shown in a murine model of myeloma [73, 74]. MM cells can overexpress the Wnt inhibitor DKK1 compared to plasma cells from MGUS patients and to normal plasma cells [75]. High DKK1

levels in BM and peripheral blood sera of MM patients correlated with the presence of bone lesions [76]. MM cells also produce other Wnt inhibitors, including sFRP-2 and sFRP-3, which can

inhibit osteoblast differentiation as well. Higher levels of these inhibitors are found in BM plasma of MM patients with bone lesions [76, 77]. Furthermore, Sclerostin, another Wnt pathway

inhibitor with a mechanism of action similar to the related protein DKK1, was also found to be overexpressed in MM cells and involved in the osteoblast suppression [78, 79]. A recent study

conducted by Bolzoni et al. [80] showed that MM cells could also inhibit osteogenic differentiation through the suppression of non-canonical Wnt co-receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan

receptor 2 (Ror2) expression in MSCs. Overexpression of Wnt family member 5 (Wnt5) or Ror2 by lentiviral vectors increased the osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs and blunted the inhibitory

effect of MM [80]. In addition to Wnt signalling inhibitors, a few other soluble factors involved in the MM cell-mediated inhibition of osteoblast differentiation of MSCs have been

identified. IL-7 can decrease runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) promoter activity and the expression of osteoblast markers in osteoblastic cells. Higher IL-7 plasma levels were

found in MM patients compared to normal subjects, and blocking IL-7 partially blunted the inhibitory effects of MM cells on osteoblast differentiation [70, 81]. Transforming growth factor-β

(TGF-β) is a potent inhibitor of terminal osteoblast maturation and mineralization. Inhibition of TGF-β signalling can not only suppress myeloma cell growth but can also enhance osteoblast

differentiation and inhibit bone destruction [82]. HGF is produced by MM cells, and its high levels in the BM plasma of MM patients correlates with those of alkaline phosphatase. HGF

inhibits in vitro bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2)-induced expression of alkaline phosphatase in both human and murine mesenchymal cells [83]. IL-3 has also been reported as a potential

osteoblast inhibitor in MM patients. In both murine and human systems, IL-3 indirectly inhibited osteoblast formation in a dose-dependent manner, and IL-3 levels in the BM plasma from MM

patients were increased in approximately 70% of patients compared to normal controls or MGUS patients [84]. In addition, it has been shown that myeloma cells promoted the release of activin

A, a member of the TGF-β superfamily, by BM stromal cells. Activin A was found to inhibit osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. The BM plasma levels of activin A were also increased

in MM patients with bone lesions, compared to those without bone lesions [85]. Treatment of 5T2MM-bearing mice with ActRIIA.muFc, a soluble form of the activin receptor, prevented

myeloma-induced suppression of bone formation, loss of cancellous bone and the development of bone lesions [86]. Moreover, TNF-α is produced by MM cells and markedly increases IL-6

production by BM stromal cells, thereby preventing MM cell apoptosis and increasing MM cell proliferation [87]. TNF-α can also inhibit the proliferation of MSCs and induce apoptosis of

mature osteoblasts [88]. Evidence was found that TNF-α produced by MM cells induces a higher growth factor independent 1 (Gfi-1) expression in MSCs resulting in repression of the Runx2 gene

and osteoblast differentiation [89]. In addition, a new mechanism for MM cell-induced suppression of osteogenic differentiation has been proposed by Fu et al. [90] These authors demonstrated

that MM cells can inhibit osteogenic differentiation of MSCs from healthy donors by rendering the osteoblasts sensitive to TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis

[90]. In addition, Vallet et al. [91] reported that MM cell-derived CCL3 exerted a strong inhibition of osteoblast function and that treating SCID-hu mice with an inhibitor of the

corresponding chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 1 (CCR1) induced an upregulation of osteocalcin expression along with osteoclast downregulation. Notch signalling has been reported to maintain

BM mesenchymal progenitors in a more undifferentiated state by suppressing osteoblast differentiation. Our group found that the Notch pathway downstream genes hairy and enhancer of

split-1(hes1), hairy/enhancer-of-split related with YRPW motif protein 1 (hey1), hey2, and heyL were considerably decreased in ND-hMSCs during osteogenesis. However, the expression of Notch

signalling in MM-MSCs did not decrease to the level of ND-MSCs, suggesting that the Notch pathway remained over-activated in MM-MSCs. The addition of the Notch pathway inhibitor DAPT or

Notch1 short interfering RNA (siRNA) could significantly enhance the impaired osteogenic differentiation ability of MM-MSCs in vitro [69]. As mentioned above, MM-hMSCs have a different miRNA

expression profile compared to ND-hMSCs. We observed that miR-135b negatively regulates MSC osteogenesis. Noticeably, miR-135b was significantly upregulated in MM-hMSCs with low alkaline

phosphatase (ALP) activity compared to ND-hMSCs. A miR135b inhibitor could enhance MM-hMSC osteogenic differentiation [13]. In addition, Zhuang et al. [92] demonstrated that MM-MSCs

expressed lower levels of long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3) compared to those from normal donors during osteogenic differentiation. Gain- and loss-of-function

studies demonstrated that lncRNA MEG3 played an essential role in the osteogenic differentiation of BM MSCs, partly by activating BMP4 transcription [92]. MSC-BASED CELL THERAPY IN MM MSCs

possess different properties that might make them an attractive choice as cellular vehicles for cell-mediated gene therapy in human malignancies. MSCs can be easily genetically manipulated

in vitro to carry anti-tumour agents to tumour sites based on their tumour-tropism migration ability. Several pre-clinical studies have applied this cell-mediated gene therapy strategy

successfully in MM. Rabin et al. [47] observed in the KMS-12-BM MM mouse model that the presence of MM cells in the BM could attract infused MSCs, suggesting that BM-derived MSCs can be good

candidates to deliver therapeutic transgenes to the MM environment in vivo. Hence, they engineered MSCs lentivirally with OPG in vitro and employed MSCs as a vehicle to deliver OPG in vivo

to treat MM-induced bone lesions. The results showed that the systemic administration of OPG-expressing MSCs reduced osteoclast activation and trabecular bone loss in the vertebrae and

tibiae of MM diseased animals. Sartoris et al. [46] also reported that the subcutaneous administration of interferon-α engineered MSCs significantly hindered the tumour growth and prolonged

the overall survival in a mouse plasmacytoma model. Moreover, Ciavarella et al. [45] demonstrated in vitro that TRAIL-expressing adipose-derived MSCs could not only directly induce myeloma

cell death but also synergistically potentiate the anti-myeloma activity of Bortezomib. The capacity to target endogenous MSCs towards committed differentiation in vivo using pharmacological

agents has recently been emphasized. Bortezomib is a clinically available proteasome inhibitor used for the treatment of multiple myeloma. It was incidentally observed that multiple myeloma

patients treated with the drug have increased serum levels of bone-specific alkaline phosphatase. Giuliani et al. [93] reported in vivo and in vitro observations that both direct and

indirect effects on the bone formation process could occur during bortezomib treatment, while Mukherjee et al. [94] further showed that bortezomib can induce MSCs to preferentially undergo

osteoblastic differentiation, in part by modulation of the bone-specifying transcription factor Runx2 in mice. Mice implanted with MSCs showed increased ectopic ossicle and bone formation

when recipients received low doses of bortezomib. This treatment increased bone formation and rescued bone loss in a mouse model of osteoporosis. Furthermore, osteoblasts and MSCs express

the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which positively regulated osteogenic differentiation. Kaiser et al. [95] demonstrated that stimulation of VDR is another mechanism for the bortezomib-induced

stimulation of osteoblastic differentiation, which suggests that supplementation with vitamin D of MM patients treated with bortezomib is crucial for optimal bone formation. Histone

deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) are also considered to be promising drugs for the treatment of MM and other cancers. There is growing evidence that some HDACis, such as trichostatin A,

valproic acid and sodium butyrate, could stimulate the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs and exhibit anabolic effects on the skeleton in addition to their anti-tumour effect [96,97,98,99].

Vorinostat (SAHA or ZolinzaTM) is a pan-inhibitor of class I and II HDAC proteins. However, two recent publications showed that high treatment frequency of Vorinostat (100 mg/kg, daily)

caused bone loss in mice [100, 101]. It is unclear why Vorinostat apparently induces an opposite effect compared to other HDACis, but it was noticed in the study of McGee-Lawrence et al.

[100] that a high treatment frequency also caused a significant toxicity (body weight loss) and even death. According to Campbell et al. [102], Vorinostat at 100 mg/kg daily

intraperitoneally for 2 consecutive days per week already showed a marked decrease in MM tumour burden, and no further improvement of the anti-MM effect occurred when the frequency of drug

treatment was increased to 5 consecutive days per week [102]. In our study, we observed that Vorinostat significantly increased in vitro the activity of ALP, the mRNA expression of

osteogenic markers and matrix mineralization in BM-derived hMSCs from both normal donors and MM patients. Importantly, with a less frequent treatment regimen, we did not observe any decrease

in bone formation in vivo in contrast to what previous publications showed [103]. These data suggest that with an optimized treatment regimen, Vorinostat can retain its anti-tumour effect

without impairment of bone formation or even with a supportive effect on osteogenesis. Further in vivo work is needed to determine an optimal treatment strategy that can kill MM cells

without impairing MSC function. Bisphosphonates are widely used in the treatment of bone loss in cancers, but the observations about their effects on MSC differentiation towards osteoblast

cells are controversial. Heino et al. [104] reported that zoledronic acid (ZA) could increase proliferation of rat mesenchymal stromal cells in vivo, but did not observe substantial effect

on osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs. However, Hu et al. [105] found that ZA-pretreated murine BM-MSCs showed increased osteogenesis in vivo. The opposite results might be related to the

concentration of ZA that was used for treatment. In the study of Hu et al. [105], it was demonstrated that non-toxic levels of ZA (0.5 μM) can upregulate the expression of the

osteogenesis-related genes Alp, osterix and bone sialoprotein in MSCs, while at higher concentrations (5 and 10 μM) ZA inhibits the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of BM-MSCs.

This opposite effect has also been observed with other anti-MM drugs, such as the HDCA inhibitor Vorinostat [103] which suggests that the drug concentration as well as the frequency and

timing of treatment might significantly influence MSC differentiation in the BM environment. CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES MSCs only constitute a small population of adult stem cells mainly

found in the BM but play an important role in a number of malignant diseases, particularly in MM and MM-induced bone disease. Compared with their normal counterparts, MSCs are abnormal in MM

patients at both the genomic and cytokine secretion levels. Moreover, they show an impaired osteogenic differentiation ability. At which level these abnormalities are intrinsic or acquired

through contact with the myeloma clone remains to be determined. Several in vitro studies have shown that some anomalies can be induced by exposing normal MSCs to myeloma cells. On the other

hand, several defects remain detectable in MM bone marrow–derived MSCs, even when the cells are cultured for a prolonged period of time without myeloma cells. This indicates that if

anomalies are myeloma cell induced, they are at least not immediately reversible in the absence of tumour cells. Multiple factors are involved in MM cell-mediated inhibition of MSC

osteogenic differentiation. Although blockade of soluble factors such as IL-3, IL-7, sFRP-2 and HGF, as well as anti-DKK1 and anti-CCR1 treatments, can partially improve bone disease in MM,

no treatment can totally correct the impairment of MM-induced MSC osteogenesis, indicating that more complex mechanisms may be involved. Drug targeting of MSCs has been proposed as a

strategy for repairing MM-induced bone lesion. Emerging data indicate that the proteasome inhibitors such as bortezomib may regulate MSC osteogenic differentiation, stimulate bone formation

and control MM bone disease. In addition to bortezomib, other new MM drugs should be further investigated for their potential MSC osteogenesis stimulatory effect. MSCs possess numerous

properties that might make them an attractive choice as a vehicle for gene therapy in human malignancies. MSCs can be easily genetically manipulated in vitro and carry anti-tumour agents to

tumour sites based on their tumour-tropism migration ability. Several studies have applied this cell-mediated gene therapy strategy successfully against different tumour types. Recently, Liu

et al. [106] also used mechanosensitive promoter-driven MSC-based vectors to deliver cytosine deaminase which could selectively target cancer metastases. With regard to MM, the application

of gene-modified MSCs for the treatment of MM is still in its infancy. Only two reports have described OPG-expressing MSCs for the treatment of MM bone lesion and TRAIL-expressing MSCs to

kill MM cells. Although the use of MSCs in cell-based therapies shows great promise in many tumour types, and MSC infusion is a promising approach to support haematopoietic recovery and to

control graft versus host disease (GVHD) in patients after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the application of MSCs in MM should be handled with extreme caution. Our data

suggest that MSCs, as the progenitors of most BM cells, could favour MM growth in vitro and in vivo and that MSC-based cytotherapy might introduce a potential risk for MM disease

progression or relapse. Ning H et al. [107] recently reported the outcome of their pilot clinical study indicating that cotransplantation of MSCs in haematologic malignancy patients can

prevent GVHD. However, the relapse rate was obviously higher than the control group, which may be explained by MSC immunomodulatory properties [107]. Although the studies from our team and

other groups showed that BM-derived MSCs have the potential to contribute to myeloma disease, MSCs from other sources, such as umbilical cord and adipose tissue, were found to inhibit MM

growth or to have no significant effect [43, 45]. Compared to BM-MSCs, MSCs derived from UC and adipose were shown to exhibit distinct biological properties related to expansion capacity,

gene expression, osteogenesis capacity and cytokine/chemokine secretion potentials [43, 108]. Therefore, the therapeutical use of MSC from non-BM tissue sources in MM is worthy of being

further investigated. In addition, there are some other issues that have to be addressed in future research and therapeutical applications of MSCs. Several groups described that murine MSCs

can undergo spontaneous transformation in vitro which is associated with increased telomerase activity, p53 loss, oncogene activation, or/and accumulated chromosomal instability

[109,110,111]. This risk of in vitro transformation or other culture-induced abnormalities must be considered when these cells are used as a model to study in vivo and/or in vitro the

biological properties of “normal” MSCs. In contrast, studies using human MSCs did not provide any evidence so far that culture expansion can result in malignant transformation and therefore

the safety of MSC therapy is currently considered to be acceptable. On the other hand, prolonged in vitro expansion might alter biological characteristics of MSCs. Therefore, it is important

to identify optimal culture conditions which allow cell expansion without affecting basic features like the primary “stemness” and differentiation potential as well as the homing properties

of MSCs. Traditionally, foetal bovine serum has been utilized as the main source of growth supplement for MSC culture in clinical protocols. However, the use of an animal-derived product

might have potential safety concerns for the recipients of MSC therapy, including possible infections and severe immune reactions. Some alternative animal-free culture conditions have been

developed, including human platelet lysates and chemically predefined serum-free culture media, which could retain all necessary characteristics attributed to MSC for potential therapeutic

use [112,113,114]. However, the long-term in vivo safety and efficacy require further investigation. Collectively, MSCs are not just passive by-standers in the MM BM microenvironment. MSCs

can be considered both as a possible therapeutic tool or a target for MM patients. The crosstalk between MSCs and MM cells is very important for MM cell growth and MM-induced bone disease.

Using MSCs as cell carriers to deliver anti-tumour factors or targeting MSCs themselves might lead to promising MM therapies, but their potential risk must be further examined. REFERENCES *

Arnulf B, Lecourt S, Soulier J, Ternaux B, Lacassagne MN, Crinquette A, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells derived from patients with

multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21:158–63. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Corre J, Mahtouk K, Attal M, Gadelorge M, Huynh A, Fleury-Cappellesso S, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal

stem cells are abnormal in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21:1079–88. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Garderet L, Mazurier C, Chapel A, Ernou I, Boutin L, Holy X,

et al. Mesenchymal stem cell abnormalities in patients with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:2032–41. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Wallace SR, Oken MM, Lunetta KL,

Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Masellis AM. Abnormalities of bone marrow mesenchymal cells in multiple myeloma patients. Cancer. 2001;91:1219–30. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Zdzisinska

B, Bojarska-Junak A, Dmoszynska A, Kandefer-Szerszen M. Abnormal cytokine production by bone marrow stromal cells of multiple myeloma patients in response to RPMI8226 myeloma cells. Arch

Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2008;56:207–21. Article CAS Google Scholar * Corre J, Labat E, Espagnolle N, Hébraud B, Avet-Loiseau H, Roussel M, et al. Bioactivity and prognostic significance

of growth differentiation factor GDF15 secreted by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in multiple myeloma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1395–406. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * André T,

Meuleman N, Stamatopoulos B, De Bruyn C, Pieters K, Bron D, et al. Evidences of early senescence in multiple myeloma bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59756. Article

PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Garayoa M, Garcia JL, Santamaria C, Garcia-Gomez A, Blanco JF, Pandiella A. Mesenchymal stem cells from multiple myeloma patients display

distinct genomic profile as compared with those from normal donors. Leukemia. 2009;23:1515–27. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * McNee G, Eales KL, Wei W, Williams DS, Barkhuizen A,

Bartlett DB, et al. Citrullination of histone H3 drives IL-6 production by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in MGUS and multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2017;31:373–81. Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Li S, Jiang Y, Li A, Liu X, Xing X, Guo Y. et al. Telomere length is positively associated with the expression of IL 6 and MIP 1α in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells of

multiple myeloma. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:2497–504. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Berenstein R, Blau O, Nogai A, Waechter M, Slonova E, Schmidt-Hieber M, et al.

Multiple myeloma cells alter the senescence phenotype of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells under participation of the DLK1-DIO3 genomic region. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:68. Article PubMed

PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Berenstein R, Nogai A, Waechter M, Blau O, Kuehnel A, Schmidt-Hieber M, et al. Multiple myeloma cells modify VEGF/IL-6 levels and osteogenic potential

of bone marrow stromal cells via Notch/miR-223. Mol Carcinog. 2016;55:1927–39. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Xu S, Cecilia Santini G, De Veirman K, Vande Broek I, Leleu X, De

Becker A, et al. Upregulation of miR-135b is involved in the impaired osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from multiple myeloma patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79752.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Todoerti K, Lisignoli G, Storti P, Agnelli L, Novara F, Manferdini C, et al. Distinct transcriptional profiles characterize bone

microenvironment mesenchymal cells rather than osteoblasts in relationship with multiple myeloma bone disease. Exp Hematol. 2010;38:141–53. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Wang X,

Zhang Z, Yao C. Agiogenic activity of mesenchymal stem cells in multiple myeloma. Cancer Invest. 2011;29:37–41. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Li B, Fu J, Chen P, Zhuang W.

Impairment in immunomodulatory function of mesenchymal stem cells from multiple myeloma patients. Arch Med Res. 2010;41:623–33. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * André T, Najar M,

Stamatopoulos B, Pieters K, Pradier O, Bron D, et al. Immune impairments in multiple myeloma bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64:213–24. Article PubMed

CAS Google Scholar * Pevsner-Fischer M, Levin S, Hammer-Topaz T, Cohen Y, Mor F, Wagemaker G, et al. Stable changes in mesenchymal stromal cells from multiple myeloma patients revealed

through their responses to Toll-like receptor ligands and epidermal growth factor. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2012;8:343–54. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Giallongo C, Tibullo D,

Parrinello NL, La Cava P, Di Rosa M, Bramanti V, et al. Granulocyte-like myeloid derived suppressor cells (G-MDSC) are increased in multiple myelomaand are driven by dysfunctional

mesenchymal stem cells (MSC). Oncotarget. 2016;7:85764–75. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ahmadvand M, Noruzinia M, Soleimani M, Abroun S. Comparison of expression

signature of histone deacetylases (HDACs) in mesenchymal stem cells from multiple myeloma and normal donors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:3605–10. PubMed Google Scholar * Nakajima S,

Fujiwara T, Ohguchi H, Onishi Y, Kamata M, Okitsu Y, et al. Induction of thymic stromal lymphopoietin in mesenchymal stem cells by interaction with myeloma cells. Leuk Lymphoma.

2014;55:2605–13. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Raphael RM, Wen J, Su J, Zhou X, et al. SDF-1α stiffens myeloma bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells through the activation of

RhoA-ROCK-Myosin II. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E219–29. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Guo X, Su J, Chen R, Berenzon D, Guthold M, et al. CD138-negative myeloma cells regulate

mechanical properties of bone marrow stromal cells through SDF-1/CXCR4/AKT signaling pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853:338–47. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Podar K, Chauhan

D, Anderson KC. Bone marrow microenvironment and the identification of new targets for myeloma therapy. Leukemia. 2009;23:10–24. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Uchiyama H, Barut

BA, Mohrbacher AF, Chauhan D, Anderson KC. Adhesion of human myeloma-derived cell lines to bone marrow stromal cells stimulates interleukin-6 secretion. Blood. 1993;82:3712–20. PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Gunn WG, Conley A, Deininger L, Olson SD, Prockop DJ, Gregory CA. A crosstalk between myeloma cells and marrow stromal cells stimulates production of DKK1 and

interleukin-6: a potential role in the development of lytic bone disease and tumor progression in multiple myeloma. Stem Cells. 2006;24:986–91. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar *

Bisping G, Leo R, Wenning D, Dankbar B, Padró T, Kropff M, et al. Paracrine interactions of basic fibroblast growth factor and interleukin-6 in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2003;101:2775–83.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Wang X, Zhang Z, Yao C. Survivin is upregulated in myeloma cell lines cocultured with mesenchymal stem cells. Leuk Res. 2010;34:1325–9. Article

PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Fuhler GM, Baanstra M, Chesik D, Somasundaram R, Seckinger A, Hose D, et al. Bone marrow stromal cell interaction reduces syndecan-1 expression and induces

kinomic changes in myeloma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1816–28. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Gupta D, Treon SP, Shima Y, Hideshima T, Podar K, Tai YT, et al. Adherence of

multiple myeloma cells to bone marrow stromal cells upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor secretion: therapeutic applications. Leukemia. 2001;15:1950–61. Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Michigami T, Shimizu N, Williams PJ, Niewolna M, Dallas SL, Mundy GR, et al. Cell–cell contact between marrow stromal cells and myeloma cells via VCAM-1 and

alpha(4)beta(1)-integrin enhances production of osteoclast-stimulating activity. Blood. 2000;96:1953–60. PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Barillé-Nion S, Barlogie B, Bataille R, Bergsagel PL,

Epstein J, Fenton RG et al. Advances in biology and therapy of multiple myeloma. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2003:ASH Education Book January 1, 2003 vol. 2003 no. 1 248–78. * Xu

S, Menu E, De Becker A, Van Camp B, Vanderkerken K, Van Riet I. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells are attracted by multiple myeloma cell-produced chemokine CCL25 and favor

myeloma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cells. 2012;30:266–79. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Kim J, Denu RA, Dollar BA, Escalante LE, Kuether JP, Callander NS, et al.

Macrophages and mesenchymal stromal cells support survival and proliferation of multiple myeloma cells. Br J Haematol. 2012;158:336–46. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Noll JE, Williams SA, Tong CM, Wang H, Quach JM, Purton LE, et al. Myeloma plasma cells alter the bone marrow microenvironment by stimulating the proliferation of mesenchymal stromal cells.

Haematologica. 2014;99:163–71. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Dotterweich J, Ebert R, Kraus S, Tower RJ, Jakob F, Schütze N. Mesenchymal stem cell contact promotes

CCN1 splicing and transcription in myeloma cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2014;12:36. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Roccaro AM, Sacco A, Maiso P, Azab AK, Tai YT,

Reagan M, et al. BM mesenchymal stromal cell-derived exosomes facilitate multiple myeloma progression. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1542–55. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

* De Veirman K, Wang J, Xu S, Leleu X, Himpe E, Maes K, et al. Induction of miR-146a by multiple myeloma cells in mesenchymal stromal cells stimulates their pro-tumoral activity. Cancer

Lett. 2016;377:17–24. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Zhao P, Chen Y, Yue Z, Yuan Y, Wang X. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells regulate stemness of multiple myeloma cell lines via

BTK signaling pathway. Leuk Res. 2017;57:20–26. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Zhang X, Sun Y, Wang Z, Huang Z, Li B, Fu J. Up-regulation of connexin-43 expression in bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cells plays a crucial role in adhesion and migration of multiple myeloma cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:211–8. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Li X, Ling W, Pennisi

A, Wang Y, Khan S, Heidaran M. Human placenta-derived adherent cells prevent bone loss, stimulate bone formation, and suppress growth of multiple myeloma in bone. Stem Cells. 2011;29:263–73.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Li X, Ling W, Khan S, Yaccoby S. Therapeutic effects of intrabone and systemic mesenchymal stem cell cytotherapy on myeloma bone disease and tumor

growth. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1635–48. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Ciavarella S, Caselli A, Tamma AV, Savonarola A, Loverro G, Paganelli R, et al. A peculiar molecular

profile of umbilical cord-mesenchymal stromal cells drives their inhibitory effects on multiple myeloma cell growth and tumor progression. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:1457–70. Article PubMed

PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Atsuta I, Liu S, Miura Y, Akiyama K, Chen C, An Y, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit multiple myeloma cells via the Fas/Fas ligand pathway. Stem

Cell Res Ther. 2013;4:111. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Ciavarella S, Grisendi G, Dominici M, Tucci M, Brunetti O, Dammacco F, et al. In vitro anti-myeloma

activity of TRAIL-expressing adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Br J Haematol. 2012;157:586–98. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Sartoris S, Mazzocco M, Tinelli M, Martini M,

Mosna F, Lisi V, et al. Efficacy assessment of interferon-alpha-engineered mesenchymal stromal cells in a mouse plasmacytoma model. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:709–19. Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Rabin N, Kyriakou C, Coulton L, Gallagher OM, Buckle C, Benjamin R, et al. A new xenograft model of myeloma bone disease demonstrating the efficacy of human mesenchymal

stem cells expressing osteoprotegerin by lentiviral gene transfer. Leukemia. 2007;21:2181–91. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Kanehira M, Fujiwara T, Nakajima S, Okitsu Y, Onishi Y,

Fukuhara N, et al. An lysophosphatidic acid receptors 1 and 3 axis governs cellular senescence of mesenchymal stromal cells and promotes growth and vascularization of multiple myeloma. Stem

Cells. 2017;35:739–53. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Sezer O, Heider U, Zavrski I, Kühne CA, Hofbauer LC. RANK ligand and osteoprotegerin in myeloma bone disease. Blood.

2003;101:2094–8. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Politou M, Terpos E, Anagnostopoulos A, Szydlo R, Laffan M, Layton M, et al. Role of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B

ligand (RANKL), osteoprotegerin and macrophage protein 1-alpha (MIP-1a) in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). Br J Haematol. 2004;126:686–9. Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Vij R, Horvath N, Spencer A, Taylor K, Vadhan-Raj S, Vescio R, et al. An open-label, phase 2 trial of denosumab in the treatment of relapsed or plateau-phase multiple

myeloma. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:650–6. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Menu E, De Leenheer E, De Raeve H, Coulton L, Imanishi T, Miyashita K, et al. Role of CCR1 and CCR5 in homing

and growth of multiple myeloma and in the development of osteolytic lesions: a study in the 5TMM model. Exp Metastas. 2006;23:291–300. Article CAS Google Scholar * Lentzsch S, Gries M,

Janz M, Bargou R, Dörken B, Mapara MY. Macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha (MIP-1 alpha) triggers migration and signaling cascades mediating survival and proliferation in multiple

myeloma (MM) cells. Blood. 2003;101:3568–73. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Zannettino AC, Farrugia AN, Kortesidis A, Manavis J, To LB, Martin SK, et al. Elevated serum levels of

stromal-derived factor-1alpha are associated with increased osteoclast activity and osteolytic bone disease in multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1700–9. Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Lee JW, Chung HY, Ehrlich LA, Jelinek DF, Callander NS, Roodman GD, et al. IL-3 expression by myeloma cells increases both osteoclast formation and growth of myeloma cells.

Blood. 2004;103:2308–15. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Fulciniti M, Hideshima T, Vermot-Desroches C, Pozzi S, Nanjappa P, Shen Z, et al. A high-affinity fully human anti-IL-6 mAb,

1339, for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7144–52. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Kudo O, Sabokbar A, Pocock A, Itonaga I, Fujikawa Y,

Athanasou NA. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-11 support human osteoclast formation by a RANKL-independent mechanism. Bone. 2003;32:1–7. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Brunetti G,

Oranger A, Mori G, Centonze M, Colaianni G, Rizzi R, et al. The formation of osteoclasts in multiple myeloma bone disease patients involves the secretion of soluble decoy receptor 3. Ann N Y

Acad Sci. 2010;1192:298–302. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Yamaguchi M, Weitzmann MN. The bone anabolic carotenoid p-hydroxycinnamic acid promotes osteoblast mineralization and

suppresses osteoclast differentiation by antagonizing NF-κB activation. Int J Mol Med. 2012;30:708–12. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Feng R, Anderson G, Xiao G, Elliott G, Leoni L,

Mapara MY, et al. SDX-308, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent, inhibits NF-kappaB activity, resulting in strong inhibition of osteoclast formation/activity and multiple myeloma cell

growth. Blood. 2007;109:2130–8. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Sun CY, Chu ZB, She XM, Zhang L, Chen L, Ai LS, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is a potential osteoclast

stimulating factor in multiple myeloma. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:827–386. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Noonan K, Marchionni L, Anderson J, Pardoll D, Roodman GD, Borrello I. A novel

role of IL-17-producing lymphocytes in mediating lytic bone disease in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;116:3554–63. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Prabhala RH,

Fulciniti M, Pelluru D, Rashid N, Nigroiu A, Nanjappa P, et al. Targeting IL-17A in multiple myeloma: a potential novel therapeutic approach in myeloma. Leukemia. 2016;30:379–89. Article

PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Fu J, Li S, Feng R, Ma H, Sabeh F, Roodman GD, et al. Multiple myeloma-derived MMP-13 mediates osteoclast fusogenesis and osteolytic disease. J Clin Invest.

2016;126:1759–72. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cozzolino F, Torcia M, Aldinucci D, Rubartelli A, Miliani A, Shaw AR, et al. Production of interleukin-1 by bone marrow

myeloma cells. Blood. 1989;74:380–7. PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Nguyen AN, Stebbins EG, Henson M, O'Young G, Choi SJ, Quon D, et al. Normalizing the bone marrow microenvironment

with p38 inhibitor reduces multiple myeloma cell proliferation and adhesion and suppresses osteoclast formation. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:1909–23. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar *

Yaccoby S, Wezeman MJ, Henderson A, Cottler-Fox M, Yi Q, Barlogie B, et al. Cancer and the microenvironment: myeloma–osteoclast interactions as a model. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2016–23. Article

PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Abe M, Hiura K, Wilde J, Shioyasono A, Moriyama K, Hashimoto T, et al. Osteoclasts enhance myeloma cell growth and survival via cell–cell contact: a vicious

cycle between bone destruction and myeloma expansion. Blood. 2004;104:2484–91. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Xu S, Evans H, Buckle C, De Veirman K, Hu J, Xu D, et al. Impaired

osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from multiple myeloma patients is associated with a blockade in the deactivation of the Notch signaling pathway. Leukemia.

2012;26:2546–9. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Giuliani N, Colla S, Morandi F, Lazzaretti M, Sala R, Bonomini S, et al. Myeloma cells block RUNX2/CBFA1 activity in human bone marrow

osteoblast progenitors and inhibit osteoblast formation and differentiation. Blood. 2005;106:2472–83. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Mori Y, Shimizu N, Dallas M, Niewolna M, Story

B, Williams PJ, et al. Anti-alpha4 integrin antibody suppresses the development of multiple myeloma and associated osteoclastic osteolysis. Blood. 2004;104:2149–54. Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Ely SA, Knowles DM. Expression of CD56/neural cell adhesion molecule correlates with the presence of lytic bone lesions in multiple myeloma and distinguishes myeloma from

monoclonal gamyelomaopathy of undetermined significance and lymphomas with plasmacytoid differentiation. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1293–9. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Fulciniti M, Tassone P, Hideshima T, Vallet S, Nanjappa P, Ettenberg SA, et al. Anti-DKK1 mAb (BHQ880) as a potential therapeutic agent for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2009;114:371–9. Article

PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Edwards CM, Edwards JR, Esparza J, Oyajobi BO, McCluskey B, Munoz S, et al. Lithium inhibits the development of myeloma bone disease in vivo. J

Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:S82. Google Scholar * Tian E, Zhan F, Walker R, Rasmussen E, Ma Y, Barlogie B, et al. The role of the Wnt-signaling antagonist DKK1 in the development of osteolytic

lesions in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2483–94. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Giuliani N, Morandi F, Tagliaferri S, Lazzaretti M, Donofrio G, Bonomini S, et al.

Production of wnt inhibitors by myeloma cells: potential effects on canonical wnt pathway in the bone microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7665–74. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar *

Oshima T, Abe M, Asano J, Hara T, Kitazoe K, Sekimoto E, et al. Myeloma cells suppress bone formation by secreting a soluble Wnt inhibitor, sFRP-2. Blood. 2005;106:3160–5. Article PubMed

CAS Google Scholar * Brunetti G, Oranger A, Mori G, Specchia G, Rinaldi E, Curci P, et al. Sclerostin is overexpressed by plasma cells from multiple myeloma patients. Ann NY Acad Sci.

2011;1237:19–23. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Gkotzamanidou M, Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Christoulas D, Moulopoulos LA, Terpos E. Sclerostin: a possible target for the

management of cancer-induced bone disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16:761–9. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Bolzoni M, Donofrio G, Storti P, Guasco D, Toscani D, Lazzaretti

M, et al. Myeloma cells inhibit non-canonical wnt co-receptor ror2 expression in human bone marrow osteoprogenitor cells: effect of wnt5a/ror2 pathway activation on the osteogenic

differentiation impairment induced by myeloma cells. Leukemia. 2013;27:451–63. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Giuliani N, Colla S, Sala R, Moroni M, Lazzaretti M, La Monica S, et

al. Human myeloma cells stimulate the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL) in T lymphocytes: a potential role in multiple myeloma bone disease. Blood.

2002;100:4615–21. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Takeuchi K, Abe M, Hiasa M, Oda A, Amou H, Kido S, et al. Tgf-Beta inhibition restores terminal osteoblast differentiation to

suppress myeloma growth. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9870. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Standal T, Abildgaard N, Fagerli UM, Stordal B, Hjertner O, Borset M, et al. HGF

inhibits BMP induced osteoblastogenesis: possible implications for the bone disease of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2007;109:3024–30. PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Ehrlich LA, Chung HY,

Ghobrial I, Choi SJ, Morandi F, Colla S, et al. IL-3 is a potential inhibitor of osteoblast differentiation in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2005;106:1407–14. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

* Vallet S, Mukherjee S, Vaghela N, Hideshima T, Fulciniti M, Pozzi S, et al. Activin A promotes multiple myeloma-induced osteolysis and is a promising target for myeloma bone disease.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5124–9. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Chantry AD, Heath D, Mulivor AW, Pearsall S, Baud'huin M, Coulton L, et al. Inhibiting

activin-A signaling stimulates bone formation and prevents cancer-induced bone destruction in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2633–46. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Hideshima T,

Chauhan D, Podar K, Schlossman RL, Richardson P, Anderson KC. Novel therapies targeting the myeloma cell and its bone marrow microenvironment. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:607–12. Article PubMed

CAS Google Scholar * Nanes MS. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha: molecular and cellular mechanisms in skeletal pathology. Gene. 2003;321:1–15. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar *

D'Souza S, del Prete D, Jin S, Sun Q, Huston AJ, Kostov FE, et al. Gfi1 expressed in bone marrow stromal cells is a novel osteoblast suppressor in patients with multiple myeloma bone

disease. Blood. 2011;118:6871–680. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Fu J, Wang P, Zhang X, Ju S, Li J, Li B, et al. Myeloma cells inhibit osteogenic differentiation of

mesenchymal stem cells and kill osteoblasts via TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6:496–504. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Vallet S, Pozzi S, Patel K,

Vaghela N, Fulciniti MT, Veiby P, et al. A novel role for CCL3 (MIP-1α) in myeloma-induced bone disease via osteocalcin downregulation and inhibition of osteoblast function. Leukemia.

2011;25:1174–81. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Zhuang W, Ge X, Yang S, Huang M, Zhuang W, Chen P, et al. Upregulation of lncRNA MEG3 promotes osteogenic

differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from multiple myeloma patients by targeting BMP4 transcription. Stem Cells. 2015;33:1985–97. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Giuliani N,

Morandi F, Tagliaferri S, Lazzaretti M, Bonomini S, Crugnola M, et al. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib affects osteoblast differentiation in vitro and in vivo in multiple myeloma

patients. Blood. 2007;110:334–8. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Mukherjee S, Raje N, Schoonmaker JA, Liu JC, Hideshima T, Wein MN, et al. Pharmacologic targeting of a

stem/progenitor population in vivo is associated with enhanced bone regeneration in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:491–504. PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Kaiser MF, Heider U,

Mieth M, Zang C, von Metzler I, Sezer O. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib stimulates osteoblastic differentiation of human osteoblast precursors via upregulation of vitamin D receptor

signalling. Eur J Haematol. 2013;90:263–72. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Lee S, Park JR, Seo MS, Roh KH, Park SB, Hwang JW, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors decrease

proliferation potential and multilineage differentiation capability of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2009;42:711–20. Article PubMed CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Schroeder TM, Westendorf JJ. Histone deacetylase inhibitors promote osteoblast maturation. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2254–63. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * de Boer J, Licht R,

Bongers M, van der Klundert T, Arends R, van Blitterswijk C. Inhibition of histone acetylation as a tool in bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2927–37. Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Cho HH, Park HT, Kim YJ, Bae YC, Suh KT, Jung JS. Induction of osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Cell Biochem.

2005;96:533–42. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * McGee-Lawrence ME, McCleary-Wheeler AL, Secreto FJ, Razidlo DF, Zhang M, Stensgard BA, et al. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA;

vorinostat) causes bone loss by inhibiting immature osteoblasts. Bone. 2011;48:1117–26. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Pratap J, Akech J, Wixted JJ, Szabo G, Hussain

S, McGee-Lawrence ME, et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor, Vorinostat, reduces tumor growth at the metastatic bone site and associated osteolysis, but promotes normal bone loss. Mol

Cancer Ther. 2012;9:3210–20. Article CAS Google Scholar * Campbell RA, Sanchez E, Steinberg J, Shalitin D, Li ZW, Chen H, et al. Vorinostat enhances the antimyeloma effects of melphalan

and bortezomib. Eur J Haematol. 2010;84:201–11. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Xu S, De Veirman K, Evans H, Santini GC, Vande Broek I, Leleu X, et al. Effect of the HDAC inhibitor

vorinostat on the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in vitro and bone formation in vivo. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34:699–709. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google

Scholar * Heino TJ, Alm JJ, Halkosaari HJ, Välimäki VV. Zoledronic acid in vivo increases in vitro proliferation of rat mesenchymal stromal cells. Acta Orthop. 2016;87:412–27. Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hu L, Wen Y, Xu J, Wu T, Zhang C, Wang J, Wang S, et al. Pretreatment with bisphosphonate enhances osteogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2017;26(2):123–32. Jan 15 Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Liu L, Zhang SX, Liao W, Farhoodi HP, Wong CW, Chen CC. et al. Mechanoresponsive stem cells to target

cancer metastases through biophysical cues. _Sci Transl Med_. 2017;9:pii: eaan2966 Article Google Scholar * Ning H, Yang F, Jiang M, Hu L, Feng K, Zhang J, et al. The correlation between

cotransplantation of mesenchymal stem cells and higher recurrence rate in hematologic malignancy patients: outcome of a pilot clinical study. Leukemia. 2008;22:593–9. Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Lin HH, Hwang SM, Wu SJ, Hsu LF, Liao YH, Sheen YS, et al. The osteoblastogenesis potential of adipose mesenchymal stem cells in myeloma patients who had received intensive

therapy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94395. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Tirode F, Laud-Duval K, Prieur A, Delorme B, Charbord P, Delattre O. Spontaneous expression of

embryonic factors and p53 point mutations in aged mesenchymal stem cells: a model of age-related tumorigenesis in mice. Mesenchymal stem cell features of Ewing tumors. Cancer Cell.

2007;11:421–9. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Miura M, Miura Y, Padilla-Nash HM, Molinolo AA, Fu B, Patel V, Seo BM, Sonoyama W, Zheng JJ, Baker CC, Chen W, Ried T, Shi S.

Accumulated chromosomal instability in murine bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells leads to malignant transformation. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1095–103. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Xu S, De

Becker A, De Raeve H, Van Camp B, Vanderkerken K, Van Riet I. In vitro expanded bone marrow-derived murine (C57Bl/KaLwRij) mesenchymal stem cells can acquire CD34 expression and induce

sarcoma formation in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;424:391–7. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Mimura S, Kimura N, Hirata M, Tateyama D, Hayashida M, Umezawa A, et al. Growth

factor-defined culture medium for human mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Dev Biol. 2011;55:181–7. Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Walenda G, Hemeda H, Schneider RK, Merkel R, Hoffmann

B, Wagner W. Human platelet lysate gel provides a novel three dimensional-matrix for enhanced culture expansion of mesenchymal stromal cells. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2012;18:924–34.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Chase LG, Yang S, Zachar V, Yang Z, Lakshmipathy U, Bradford J, et al. Development and characterization of a clinically compliant xeno-free culture

medium in good manufacturing practice for human multipotent mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012;1:750–8. Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar Download

references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was sponsored by the “Wetenschappelijk Fonds Willy Gepts”, and the foundation “Kom op Tegen Kanker” (Emmanuel van der Schueren grant). XS was supported

by a China Scholarship Council (CSC)-VUB scholarship. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Lung Cancer Surgery, Lung Cancer Institute, Tianjin Medical University

General Hospital, Tianjin, China Song Xu * Department Hematology- Stem Cell Laboratory, Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel (UZ Brussel), Brussels, Belgium Kim De Veirman, Ann De Becker &

Ivan Van Riet * Research Group Hematology and Immunology-Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Myeloma Center Brussels, Brussels, Belgium Kim De Veirman, Karin Vanderkerken & Ivan Van Riet

Authors * Song Xu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kim De Veirman View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Ann De Becker View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Karin Vanderkerken View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ivan Van Riet View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Ivan Van Riet.

ETHICS DECLARATIONS CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original

author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the

article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use

is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Xu, S., De Veirman, K., De Becker, A. _et al._ Mesenchymal stem cells in multiple

myeloma: a therapeutical tool or target?. _Leukemia_ 32, 1500–1514 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-018-0061-9 Download citation * Received: 05 August 2017 * Revised: 08 January 2018 *

Accepted: 16 January 2018 * Published: 22 February 2018 * Issue Date: July 2018 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-018-0061-9 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with

will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative