- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Governments around the world are investing in nanotechnology in the hopes that applications in the biotechnology and chemical industry will help turn faltering economies around. You have

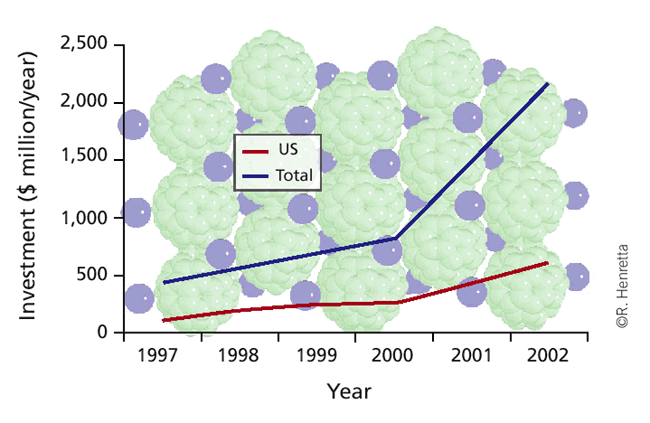

full access to this article via your institution. Download PDF At a time when most economies are floundering, global government funding for nanotechnology continues an upward spiral (Fig.

1). The United Kingdom is the latest country to pump up its spending on nanotechnology, having announced in June a near doubling of its commitment with the infusion of £90 ($141) million

into its MicroNanoTechnology Network fund. And in the United States, the Army recently put up $50 million to create a new institute—the Institute for Collaborative Biotechnology—which brings

together researchers from the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB; Santa Barbara, CA, USA), Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT; Cambridge, MA, USA) and California

Institute of Technology (Caltech; Pasadena, CA, USA) in an interdisciplinary program to engineer new materials from biological systems. Worldwide, investment in nanotechnology by government

organizations has increased roughly sevenfold in the past six years, from $432 million in 1997 to almost $3 billion in 2003 (ref. 1). The United States took the early lead in funding this

research area, being the first to announce a cross-agency initiative, the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI; Arlington, VA, USA) in 2000 (ref. 2). Although the United States still

accounts for nearly a third of nanotechnology spending worldwide, it no longer stands alone: in the three years since previous US president Bill Clinton formed the NNI, some 35 countries

have instituted programs in the area in what might be described as a feeding frenzy over this burgeoning technology. But it would be wrong to think that this is just about science; what it

is really about is jobs. According to Mark Modzelewski of the US nanotech industry association NanoBusiness Alliance (New York, NY, USA), politicians see nanotechnology as the next growth

industry, and are vying for companies to locate in their districts in the hopes of shoring up sagging economies. The thinking is, “Biotech created jobs, the internet created jobs, wireless

created jobs, nanotech can create jobs. I want them in my state,” says Modzelewski. PUTTING THE BIO IN NANOTECHNOLOGY And how does nanobiotechnology fare when it comes to funding? According

to figures compiled by the NNI, biotechnology research currently gets 10% or less of global government nanotechnology funds3. Venture money, on the other hand, is preferentially going to

nanobiotechnology over other kinds of nanotechnology. More than 50% of venture capital in nanotechnology in the past four years has funded companies doing nanobiotechnology (see p. 1144).

Why the disconnect between private and public funding? The answer is partly historical, says Jeffrey Schloss, program director of technology development at the National Human Genome Research

Institute (NHGRI; Rockville, MD, USA). The agencies that have traditionally supported this brand of research (before the moniker 'nanotechnology' was even applied to it), such as

the Department of Defense (Washington, DC, USA), have small life science programs. These agencies still give out the lion's share of nanotechnology money, although the National

Institutes of Health's (NIH; Bethesda, MD, USA) contribution is substantial and growing (see Table 1). Secondly, biologists have been slow to warm to the concept of nanotechnology as

something new. According to Schloss, molecular biologists have been working at the nanoscale for their entire careers. “It's been their bread and butter,” he says. Furthermore,

nanotechnology has no particular cachet at the NIH, where the goal is simply to find the best way to solve problems. “If it happens to be nanotechnology, then great,” says Schloss.

Nonetheless, a search of the NIH database reveals that it currently funds over 200 grants with some connection to nanotechnology, many for creating tools—probes and sensors—for working at

the nanoscale (see p. 1137 for more examples). But to take advantage of these large federal programs, biologists will need to change the way they work, says Modzelewski. Nano-biotechnology

begs for collaboration between materials scientists, physicists and biologists—a nontraditional grouping. Modzelewski has seen instances where departments within the same university are

competing against each other for grants. “That's not going to fly in this field,” he says. “The groups winning the grants [like the MIT- UCSB-Caltech consortium] are top-notch

universities who look to see at how to collaborate with the best of the best. You'll see a lot more of that, and there's a need, especially with the [large amount of available]

dollars.” The NIH currently has two programs explicitly directed at nanotechnology: Nanoscience and Nanotechnology in Biology and Medicine, which was established in 2002 and is about to

embark on its second round of funding, and the Bioengineering Nanotechnology Initiative, which was established four years ago. But Schloss's approach at the NHGRI has been to build a

program with a solid scientific foundation, where interactions between biologists and physical scientists are built in, and then to let the relationships evolve naturally. “We are trying to

make our investigators aware of the programs, let it grow from the ground up—just like nanotech, bottom-up—rather than imposing it.” But it's hard, he says. “Communicating between the

groups can be difficult and there are only a few good examples of nanotechnology discoveries that have applications in biology. It's been very exciting from a material science point of

view, but there are still many hurdles to translate to biomedical relevance.” NO COUNTRY LEFT BEHIND By almost every measure, the United States is the dominant player in nanotechnology

(Figs. 2 and 3), but the nanocraze doesn't stop at US borders. In addition to the United Kingdom's initiative, the governments of Japan, China, Germany, Canada and France have all

ponied up sizable sums for nanotechnology research in their countries (Table 2). Determining how much money is being spent on the industry is difficult, because what governments invest does

not include private funding and therefore may be just the tip of the iceberg. Chris Piercy of the Northern California Nanotech Initiative (Menlo Park, CA, USA), a regional economic

development group, estimates that Japan has been outspending the United States by $1 billion a year, although the official numbers would show that funding in Japan is just now exceeding the

US government's outlay. And based on buying power, the People's Republic of China beats all others in their commitment to nanotechnology. Already this commitment has paid off for

the Chinese; according to a study published in _Asia Pacific Nanotech Weekly_, in the past few years, the numbers of publications on nanotechnology coming from China climbed to several

hundred a year, —second only to the United States4. Furthermore, an analysis by Cientifica (Las Rosas, Spain), a nanotechnology information company, shows that in some areas, such as the

involvement of large corporations or academic institutions, the United States might be slightly outpaced by Japan and Europe, respectively (Fig. 4; ref 5). According to an analysis of the

European Union's sixth framework done by the European Nanotech Alliance6, the countries with the largest research and development (R&D) expenditures for nanotechnology in general

are Germany, France and the United Kingdom, while those with greatest interest in nanobiotechnology are Sweden, Denmark and Belgium. In fact, when calculated as a percentage of the national

income, Sweden and Finland outspend Germany and France overall, with Sweden contributing over 3% of its national income to nanotechnology R&D, whereas France contributes barely 2%.

STAYING OUT IN FRONT There is a general agreement that the desire to maintain a global lead is driving more dollars into nanotechnology in the United States. Steve Empedocles, director of

business development at Nanosys (a nanotechnology platform company based in Palo Alto, CA, USA), says that right now the United States is in the lead, but other countries are putting huge

amounts of money toward catching up. “It's a lot easier to defend [the US] position rather than recapture it if we lose it,” he says. The Bush administration places a high priority on

nanotechnology, putting it second on its list of R&D priorities. (Only combating terrorism ranks higher.) Accordingly, the Bush administration's 2005 budget calls for nearly a 10%

increase for nanotechnology research, well above the modest 2–3% increases under discussion for the NIH. With that kind of support from the top levels of government, both branches of the US

Congress have jumped on the nanobandwagon; two nanotechnology funding bills are presently making their way through the legislature. The Senate's version (S. 189) earmarks $4.7 billion

over five years for nanotechnology research and calls for expanding the role of the government in carrying out the research; the House version (H.R. 766) provides $2.36 billion over three

years, calls for the creation of a permanent governmental agency to oversee research in nanotechnology, and sets aside 20% of the funds for graduate education. According to Modzelewski, who

now sits on the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, this puts nanotechnology only slightly behind the space program in the amount of funding garnered by a single

industry. HOPE OR HYPE? There is reason for biologists to be hopeful, because the funding landscape for nano-biotechnology could change soon. As early as next year, Mihail Roco, chair of the

Nanoscale Science, Engineering and Technology Subcommittee at the NNI, expects that 25% of the funding will go to nanobiotechnology, and the long-term prospects, he believes, are even

better. Ten years from now he expects the focus of these converging technologies to be on improving the human condition—“from learning faster, or maintaining capabilities as you age or

improving mental capacity. I predict by 2015 at least half of all pharmaceuticals will be based on nanotechnology,” he says. But critics question why the federal government should be

investing such huge sums in nanotechnology, and whether governments and legislatures are being sold unrealistic promises in order to justify infusing large sums into research. In one of few

critical notes in a surprisingly positive report on new technologies published by the Greenpeace Environmental Fund, Doug Parr, its chief scientific officer, wonders whether nanotechnology

is “really a convenient label for a variety of scientific disciplines which serves as a way of getting money from Government budgets.7” The US National Science Foundation estimates that

nanotechnology will become a trillion-dollar industry within the next decade, but in _The Economist_, and elsewhere, a cautionary note has been sounded against “recklessly setting high

expectations for the economic benefits8”, because unrealized hopes could hinder the potential for private investment, which is the next step to commercializing the technologies. NNI's

Roco makes a case for funding, however, claiming nanotechnology is a special case. “The field is too broad for a single discipline or industry to pick it up,” he says. “Most advances [in

nanotechnology] are coming from cross-cutting different disciplines. The role of the government is quite clear. Without this cross-disciplinary and cross-field development, and a systematic

way to cover the basic knowledge, the field would develop much slower.” And from Roco's vantage point, advancement has been anything but slow. Three years ago, when the NNI was setting

objectives for the initiative, the organization predicted it would be 20–30 years before some of their goals would be achieved. He says that now those estimates have been reduced to 5–10

years. REFERENCES * Roco, M. _Government Nanotechnology Funding: An International Outlook_ (National Nanotechnology Initiative, Arlington, VA, USA, June 2003). Google Scholar * Fox, J.L.

_Nat. Biotechnol._ 18, 821 (2000) * Roco, M. _Curr. Opin. Biotechnol._ 14, 337–346 (2003). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lui, L. Asia Pacific Nanotech Wkly. 1, 13 (2003). * Cientifica.

_The Nanotechnology Opportunity Report_ edn. 2 (Cientifica, Las Rosas, Spain, June 2003). * Roman, C. _How Nano is Europe?_ (European NanoBusiness Association, Brussels, Belgium, November

13, 2002). Google Scholar * Huw Arnell, A. Future Technology, Today's Choices. A Report for Greenpeace Environmental Trust (London, UK, July 2003). * Anonymous. _The Economist_, p. 84,

December 5, 2002. * _Asian Nanotech Update_ (ATIP02.005) (Asian Technology Information Program, Tokyo, Japan, 2002). Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Nature

Biotechnology's Senior Editor for News & Features, Laura DeFrancesco Authors * Laura DeFrancesco View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE DeFrancesco, L. Little science, big bucks. _Nat Biotechnol_ 21, 1127–1129 (2003).

https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1003-1127 Download citation * Issue Date: 01 October 2003 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1003-1127 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with

will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(319x0:321x2)/people_social_image-60e0c8af9eb14624a5b55f2c29dbe25b.png)