- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Cleavage of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) by enterovirus proteases during infection leads to the shutoff of cellular cap-dependent translation, but does not affect the

initiation of cap-independent translation of mRNAs containing an internal ribosome entry site (IRES). Death-associated protein 5 (DAP5), a structural homolog of eIF4G, is a translation

initiation factor specific for IRES-containing mRNAs. Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) is a positive single-stranded RNA virus and a primary causal agent of human myocarditis. Its RNA genome harbors

an IRES within the 5′-untranslated region and is translated by a cap-independent, IRES-driven mechanism. Previously, we have shown that DAP5 is cleaved during CVB3 infection. However, the

protease responsible for cleavage, cleavage site and effects on the translation of target genes during CVB3 infection have not been investigated. In the present study, we demonstrated that

viral protease 2A but not 3C is responsible for DAP5 cleavage, generating 45- and 52-kDa N- (DAP5-N) and C-terminal (DAP5-C) fragments, respectively. By site-directed mutagenesis, we found

that DAP5 is cleaved at amino acid G434. Upon cleavage, DAP5-N largely translocated to the nucleus at the later time points of infection, whereas the DAP5-C largely remained in the

cytoplasm. Overexpression of these DAP5 truncates demonstrated that DAP5-N retained the capability of initiating IRES-driven translation of apoptosis-associated p53, but not the prosurvival

Bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) when compared with the full-length DAP5. Similarly, DAP5-N expression promoted CVB3 replication and progeny release; on the other hand, DAP5-C exerted a

dominant-negative effect on cap-dependent translation. Taken together, viral protease 2A-mediated cleavage of DAP5 results in the production of two truncates that exert differential effects

on protein translation of the IRES-containing genes, leading to enhanced host cell death.

Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3), a primary cause of viral myocarditis, is associated with sudden, unexpected death,1 dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure.2 The CVB3 genome consists of a single

open reading frame, which is translated to a polyprotein, and subsequently processed by viral proteases 2A and 3C. Similar to other picornaviruses, the CVB3 genome is linked to a small viral

peptide, Vpg, rather than a 7-methyl guanosine cap structure at its 5′ terminus. Thus, CVB3 RNA is translated by a cap-independent mechanism and is driven by an internal ribosome entry site

(IRES) harbored in the 5′ untranslated region (5′-UTR).3, 4

Viral proteases actively suppress multiple host cell activities that help the virus evade host defense mechanisms, promote viral replication and promote host cell apoptosis. For example,

enterovirus proteases can cleave eukaryotic translation initiation factors 4GI (eIF4GI)5, 6, 7 and eIF4GII.8, 9 Picornavirus proteases have also been reported to cleave other canonical

translation initiation factors in the cap-dependent translation initiation complex, such as eIF5B10 and eIF4A.11 Additionally, viral protease 3C has been demonstrated to cleave Ras-GAP SH3

domain-binding protein 1 (G3BP1), a key nucleating protein in stress granule formation, at late time points of infection.12, 13 G3BP1 cleavage causes stress granule disassembly12 and leads

to the release of translation initiation factors that may be hijacked for viral polyprotein translation. Accumulating evidence implies that viral proteases have crucial roles in modulating

viral and host gene expression through cleavage of various host protein factors involved in mRNA transcription and cap-dependent translation.

Death-associated protein 5 (DAP5) is a eukaryotic translation initiation factor that preferentially initiates cap-independent translation.14 This 97-kDa protein is homologous with the

central region of canonical translation initiation factor eIF4GI. DAP5 contains binding sites for eIF4A and eIF3, but lacks an eIF4E site, the mRNA cap-binding protein.14 DAP5 initiates

translation of proteins specifically expressed during development, cell cycle regulation and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress conditions, where global cap-dependent translation is

compromised.15, 16 It has been reported that DAP5 regulates IRES-driven translation of Bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2), p53, XIAP (X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein), CDK1 (cyclin-dependent

kinase 1), c-Myc and other IRES-containing genes under conditions of stress, growth and apoptosis.17, 18, 19 DAP5 mRNA also contains an IRES in its 5′-UTR, and is proficient in promoting its

own translation, generating a positive feedback loop for its expression.14, 15 Additionally, DAP5 may undergo post-translational modifications, such as cleavage by caspases during

apoptosis, generating a truncated, yet functional 86-kDa form of DAP5 that is more potent and efficient at translation initiation.14

The role of DAP5 in initiation of IRES-driven translation has been studied in various model systems but not in the setting of viral infection. In the present study, we demonstrated that DAP5

is cleaved during CVB3 infection by protease 2A but not 3C. Further, we identified amino-acid reside G434 as the site of 2A cleavage. Once cleaved, DAP5 N-terminal truncate (DAP5-N) largely

translocates into the nucleus, whereas the DAP5 C-terminal truncate (DAP5-C) remains primarily within the cytoplasm. Our data indicate that DAP5-N retains IRES-mediated translation;

however, it differentially regulates the IRES-containing genes involved in cell growth and apoptosis compared with the wild type (WT) DAP5. Exogenous expression of DAP5-N or DAP5-C induces

more cell death when compared with the WT DAP5. Further, viral capsid protein 1 (VP1) as well as viral titer is higher in DAP5-N-overexpressing cells during the late phase of infection (7 h

post infection (hpi)) compared with that in WT (WT DAP5) or an uncleavable point mutant of DAP5 (glycine 434 to glutamic acid-mutated DAP5 (G434E DAP5)). Thus, viral protease 2A cleavage of

DAP5 produces a cleavage product that robustly contributes to viral replication and viral-induced apoptosis, facilitating CVB3 progeny release.

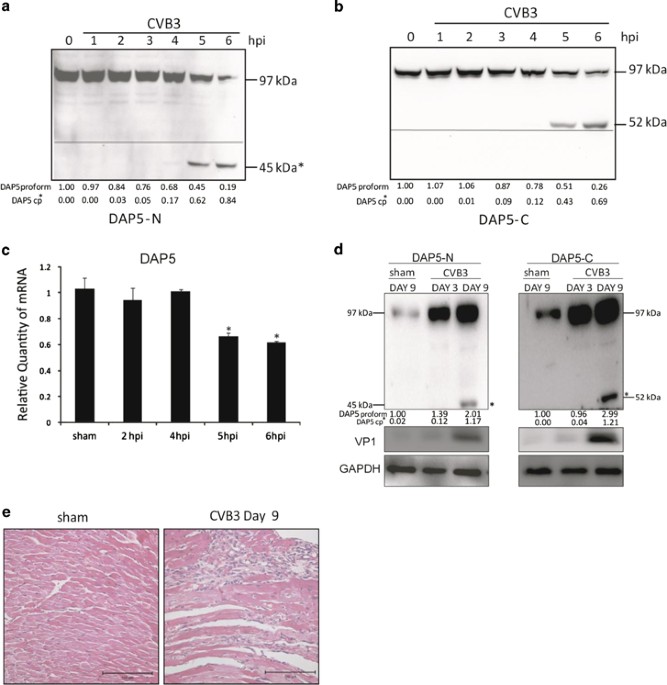

During CVB3 infection, we observed cleavage of DAP5 indicated by accumulation of ~45-kDa DAP5-N and ~52-kDa DAP5-C at 5 hpi in HeLa cells (Figures 1a and b). This finding suggests that DAP5

is not degraded during CVB3 infection, but cleaved into truncated fragments. However, at later time points, the sum of proform and cleavage products does not equal the total level of DAP5

early in infection, potentially because of altered expression of DAP5. To verify this, quantitative RT-PCR (q-RT-PCR) was performed. DAP5 transcription was downregulated at 5 and 6 hpi

(Figure 1c). To investigate whether the cleavage of DAP5 also occurs in vivo, a CVB3-infected myocarditis mouse model was used. Mouse heart tissue was harvested at 3 and 9 days post

infection (dpi). Cleavage of DAP5 to 45-kDa DAP5-N and 52-kDa DAP5-C fragments were observed (Figure 1d). In contrast to in vitro DAP5 expression, DAP5 was upregulated relative to controls

in mouse hearts. This may be because of a lower percentage of CVB3-infected cells in the myocardium compared with that in tissue culture cells. This may also explain the relatively low

abundance of DAP5 cleavage products in vivo versus in vitro, as viral infection is required for cleavage. Additionally, we found that at 9 dpi, heart tissue showed immune cell infiltration,

that is, myocarditis (Figure 1e). Our findings indicate that the cleavage of DAP5 occurs both in vitro and in vivo.

DAP5 is cleaved into N- and C-terminal-truncated forms during CVB3 infection in vitro and in vivo and is transcriptionally downregulated. HeLa cells were infected with CVB3 at 10 MOI

(multiplicity of infection) and collected at the indicated time points after infection. Lysates were analyzed by western blot with the indicated N-terminal (a) and C-terminal (b) DAP5

antibodies against the 45- and 52-kDa product, respectively. The line indicates ~50-kDa. *N- or C-terminal DAP5 cleavage product (cp). (c) DAP5 mRNA transcription levels were determined by

q-RT-PCR using the total RNA isolated from cells described above. DAP5 mRNA is downregulated at 5 and 7 hpi in HeLa cells by ~40% relative to sham-infected controls. (d) A/J mice at 4 weeks

of age were infected with CVB3 at 105 pfu or sham-infected with PBS as a control. Hearts were collected at 3 and 9 dpi. Harvested heart tissue was lysed and analyzed by western blot using

the N- and C-terminal-specific antibody. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (e) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of A/J mice heart tissue at 9 dpi. Protein levels of pro- and cleaved

forms of DAP5 were quantitated by densitometry using the NIH ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/index.html) and normalized to GAPDH or β-actin. Values are presented under each blot,

with sham levels set to 1.00

To determine if viral proteases are responsible for cleavage of DAP5, plasmids expressing WT FLAG-tagged DAP5 and protease 2A or 3C via IRES-driven cap-independent translation were

co-transfected into HeLa cells, and cleavage was determined by western blot. Our laboratory previously showed that caspases are unable to cleave DAP5 into 45- and 52-kDa fragments7 and that

transient transfection of plasmids expressing CVB3 2A or 3C does not induce cleavage of DAP5. This was likely due to the use of a cap-dependent classical expression plasmid, which would be

inactivated once the synthesized protease cleaved eIF4G and other canonical translation initiation factors. As 2A processivity of eIF4G may be higher compared with 2A processivity of DAP5,

the loss of 2A expression may have mitigated any detectable result. To verify this, we co-transfected HeLa cells with WT DAP5 and pIRES-2A or pIRES-3C. The 45-kDa DAP5-N products were only

observed in the 2A-expressing cells, suggesting that viral protease 2A is responsible for the cleavage of DAP5 during CVB3 infection (Figure 2a). To confirm that these plasmids expressed

active 2A and 3C, the cleavage of endogenous, known substrates of 2A and 3C was measured. Figure 2b shows that endogenous DAP5 was cleaved by 2A but not 3C. Other known substrates, eIF5B and

eIF4G,10, 20, 21 were cleaved either by 2A or 3C (Figures 2c and d). Additionally, the cleavage of eIF4G occurred at 24h, compared with 48 h after transfection for DAP5, suggesting that 2A

processivity of eIF4G is in fact faster than 2A processivity of DAP5.

Viral protease 2A but not 3C cleaves overexpressed WT FLAG-DAP5 and endogenous DAP5 into 45- and 52-kDa truncates. (a) pIRES-2A or 3C plasmid was co-transfected into HeLa cells with WT

FLAG-DAP5. As a control, HeLa cells were co-transfected with an empty pIRES vector and WT FLAG-DAP5 or with WT FLAG- DAP5 only. Cell lysates were collected 48 h after transfection and

analyzed by western blot using an anti-FLAG antibody. β-actin was used as a loading control. (b) pIRES vector, pIRES-2A or pIRES 3C was transfected into HeLa cells. Lysates were collected

for western blot analysis of endogenous 45-kDa DAP5-N. *DAP5 cleavage product (cp). Densitometric analysis was performed as indicated in Figure 1, with values presented under each blot. As a

control, western blot was conducted on eIF4GI and eIF5B, to verify pIRES-2A and 3C constructs were effective at cleaving their respective substrates (c and d)

According to the molecular mass of the cleavage products DAP5-N and DAP5-C, we proposed that the cleavage site is located upstream of the middle region of DAP5 protein (Figure 3a). Further,

we narrowed down the potential DAP5 cleavage sites by using the reported 2A attack sites as a guide.22 Additionally, bioinformatics prediction using the NetPicoRNA 1.0 software

(http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetPicoRNA/) (data not shown) was performed. Based on this available information, we proposed that glycine 434 might be the site for DAP5 cleavage. For

verification, a point mutation changing G434E was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis (Figure 3b) in the FLAG-tagged DAP5 construct, referred to as G434E DAP5. Cells expressing WT DAP5

showed the 45-kDa cleavage product at the 6 hpi, whereas cells expressing G434E-DAP5 remained uncleaved (Figure 3c).

Glycine 434 is the site of 2A cleavage of DAP5 during CVB3 infection. (a) Schematic structures of eIF4G and DAP5 as well the known binding sites for proteins involved in translation

initiation. The red dashed line indicates the proposed 2A cleave site at amino-acid residue 434 of DAP5 protein. (b) Sequence structure illustrating the site-directed mutagenesis at glycine

434 of DAP5. (c) HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged WT DAP5 construct or G434E DAP5 mutant for 48 h and subsequently infected with CVB3 at an MOI (multiplicity of infection) of 10

or sham-infected with PBS. Lysates were collected at 6 hpi and analyzed by western blot to detect DAP5 using an anti-FLAG antibody. *DAP5 cleavage product (cp). Densitometric analysis was

performed as indicated in Figure 1, with values presented under each blot

To determine if the subcellular localization of the DAP5 cleavage products differs from that of WT DAP5, FLAG-tagged DAP5-N (from N terminus to G434) and HA-tagged DAP5-C (from G434 to the C

terminus) expression plasmids (Figure 4a) were generated. Following transfection, lysates were subjected to nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation. WT DAP5 (100%) and DAP5-C (87%) remained

mainly in the cytoplasm (Figure 4b). However, a significant portion of DAP5-N localized to the nucleus (45%). Further confirmation was provided by immunostaining. The ectopic expression of

the cleavage products resulted in nuclear translocation only for DAP5-N (Figure 4c). Next, we determined whether ectopic expression of viral protease 2A could cause cleavage of DAP5 and

subsequent nuclear translocation of the N-terminal portion of DAP5. Figure 4d demonstrates that in WT DAP5/pIRES-2A-transfected cells the N-terminal FLAG tag portion of WT DAP5 translocated

to the nucleus, whereas the C-terminal HA portion remained in the cytoplasm. However, in G434E DAP5/pIRES-2A-transfected cells the majority of the DAP5 proteins were distributed in the

cytoplasm, similar to cells expressing WT DAP5 co-transfected with empty vector. Last, WT DAP5-transfected cells show DAP5 nuclear translocation beginning at 5 hpi with native CVB3 (Figure

4e). These results demonstrate that the viral protease 2A cleavage of DAP5 at G434 during CVB3 infection results in a partial nuclear translocation of the N-terminal DAP5.

DAP5-N translocates to the nucleus, whereas G434E DAP5 and DAP5-C remain in the cytoplasm. (a) Schematic structures of clones of the DAP5-N and DAP5-C. The FLAG and HA tags as well as the

binding sites of interacting proteins involved in translation initiation are indicated. The numbers are the specific amino-acid positions for the binding sites. (b) Western blot analysis of

cellular distribution of WT DAP5, DAP5-N and DAP5-C after transfection. HeLa cells were transfected with WT DAP5 (FLAG), DAP5-N (FLAG) or DAP5-C (HA) for 48 h. Nuclear and cytoplasmic

proteins were isolated using NE-PER Kit (Thermo Scientific). Histone-1 was used as a nuclear purity control and β-actin was used as a loading control. Densitometric analysis was performed as

in Figure 1. Values are displayed as percentages of nuclear and cytoplasmic protein values. (c) Confocal imaging of intracellular localization of WT DAP5, DAP5-N and DAP5-C after

transfection. HeLa cells were transfected as described in (b). Cells were immunostained with FLAG (WT and DAP5-N) or HA (DAP5-C) antibody and probed with Alexa Fluor 488 (green for WT and

DAP5-C) or Alexa Fluor 594 (red for DAP5-N). DAPI staining was used to image nuclei (blue). (d) Confocal imaging of FLAG-WT DAP5-HA, or FLAG-G434E-DAP5, co-transfected with pIRES vector or

protease 2A-expressing cells. HeLa cells were co-transfected with a plasmid expressing WT DAP5 tagged with N-terminal FLAG (columns 1 and 2) and a C-terminal HA (columns 5 and 6) and either

pIRES empty vector or 2A-expressing pIRES-2A plasmid. Cells co-transfected with the G434E DAP5 and pIRES empty vector or pIRES-2A (columns 3 and 4) are additional controls. Cellular

distribution of the cleavage products were detected by immunostaining for FLAG or HA using secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (green) and imaged by confocal

microscopy. (e) Confocal imaging of intracellular localization of WT DAP5 (N-terminal FLAG, C-terminal HA-tagged) or G434E DAP5 in sham (columns 1 and 3) or CVB3-infected cells (columns 4

and 9). HeLa cells were transfected with plasmid for 48 h and subsequently infected with 10 MOI (multiplicity of infection) CVB3 for 5 or 7 h or sham-infected with PBS. Cellular distribution

of WT DAP5-FLAG or -HA and FLAG-G434E DAP5 were detected by immunostaining of FLAG or HA and imaged by confocal microscopy as described for (d)

We sought to determine the effect of DAP5 cleavage on CVB3 replication. Cleavage percentages for each time point were calculated relative to proform and normalized to β-actin (Figure 5d). WT

DAP5-transfected samples show DAP5 cleavage at 5 hpi (Figure 5a), whereas G434E DAP5-transfected samples show only full-length DAP5 with anti-FLAG antibody; anti-DAP5 does detect a small

amount of cleaved endogenous DAP5 without FLAG tag (Figure 5a). Compared with empty vector-transfected cells, WT DAP5 induced 1.72-fold VP1 expression, whereas G434E DAP5 showed 0.48-fold

expression (Figure 5e) at 7 hpi. This prompted us to examine the effect of DAP5-N and DAP5-C overexpression during CVB3 infection. Figure 5b demonstrates that ectopically expressed DAP5-N

during CVB3 infection induces 2.5-fold VP1 translation compared with cells overexpressing DAP5-C, which remained equal to the vector (Figure 5f). These data suggest that viral protease 2A

cleavage of DAP5 and subsequent generation of the N-terminal truncated form aid in viral replication. Data were further confirmed by knocking down DAP5-specific small interfering RNA

(siDAP5) (Figure 5c), indicating that at 5 and 7 hpi, siRNA treatment induced 3.12- and 3.97-fold VP1 expression, respectively (Figure 5g).

Cleavage of DAP5 during CVB3 infection enhances VP1 production and siRNA knockdown of DAP5 suppresses VP1 production. (a) HeLa cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 vector, WT DAP5 or G434E

DAP5 for 48 h and subsequently infected with 10 MOI (multiplicity of infection) CVB3. Lysates were collected at the indicated time points and probed by western blot using antibodies against

endogenous DAP5, FLAG-DAP5 and VP1. β-Actin was used as a loading control (b) HeLa cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 vector, DAP5-N or DAP5-C and subsequently infected with 10 MOI CVB3.

Lysates were collected at the indicated time points and probed by western blot using antibodies against FLAG (DAP5-N), HA (DAP5-C) or VP1. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (c) HeLa

cells were transfected with DAP5-specific siRNA (siDAP5) to knockdown DAP5 expression and then infected with CVB3. Cell lysates were harvested at the indicated time points after infection

for the analysis of DAP5 cleavage fragment and viral VP1 production. Scrambled small interfering RNA (scr) was used as a control. (d) DAP5 proform protein was quantified by densitometric

analysis as described in Figure 1. Sham protein levels were set as 100% and subsequent values were calculated as percentages relative to sham protein levels. (e–g) VP1 protein production in

(a–c) was quantified by densitometric analysis using the ImageJ (NIH) program and normalized to the corresponding controls and the data are presented as means±S.D. of three independent

experiments in (d–f), respectively. *P