- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

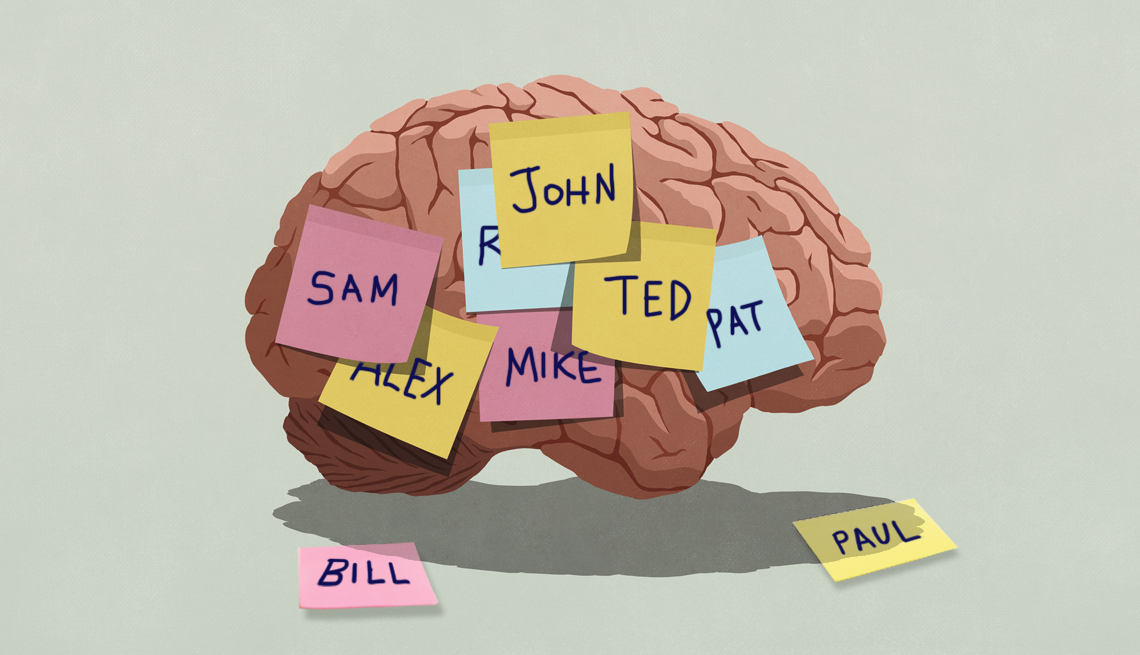

Many people can remember being called by the wrong name as a kid, often by an exhausted mother who ran through the names of every creature in the household — including the family dog — until

hitting the name she meant to say in the first place. As adults, people often repeat the same mistakes, calling one child or grandchild by the name of another. Does this mean we’re cracking

up? Not at all. “It’s completely normal to mix up names, especially within categories of related names,” such as children’s names, says Neil Mulligan, professor of psychology and

neuroscience at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In a study led by Samantha Deffler, an associate professor of psychology at York College of Pennsylvania, and her colleagues,

researchers found that about half of college students interviewed reported being called the wrong name by someone familiar to them. In 95 percent of those cases, the naming mistake was made

by a family member. Parents and grandparents aren’t the only ones who slip up. In the study, 38 percent of students also reported having called a familiar person by the wrong name, most

often a family member. You don’t have to be a scientist to notice a pattern here. When we call someone by the wrong name, we typically use the name of a similar or related person, such as a

family member or close friend. That’s because “the brain stores information in networks” of related terms, says Judith Heidebrink, M.D., a research professor of Alzheimer’s disease, a

professor of neurology and co-division chief of the cognitive disorders program at the University of Michigan Medical School. “You’re much more likely to substitute names that sound similar

or that are tied into a category in the strongest way,” Heidebrink says. Deffler’s study uncovered other patterns about our verbal blunders. For example, the people making the mistakes are

almost always older than the people they misname, who tend to be people that the speakers see frequently. Women were slightly more likely than men to mix up names, as well as report having

their own names mixed up.