- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION: Central Cord Syndrome (CCS) is the most common of the spinal cord injury syndromes. Few cases have been presented with gunshot wound (GSW) as a cause of a central cord

syndrome, and none, to our knowledge, has been presented without any evidence of central canal bullet/bone fragments. CASE PRESENTATION: A 27-year-old male suffered two close-range gunshot

wounds, one to the left neck and one to the left shoulder. CT scan showed C5 spinous process fracture and paraspinal muscle hemorrhage without evidence of central canal stenosis or

bullet/bone fragments. Physical examination showed severe weakness and dysesthesias in bilateral upper extremities and mild weakness in bilateral lower extremities. Diagnosis of central cord

syndrome was made. He was treated conservatively and started inpatient rehabilitation. Four months post injury, the patient had almost full recovery with only left proximal arm and

bilateral distal hand weakness. DISCUSSION: Only four cases of CCS caused by GSW have been reported in the literature. Some suggested algorithms exist regarding the management of these

patients, but still cases should be individualized depending on the specific nature of their presentation. The prognosis for patients with CCS tends to be favorable in regaining sensory,

bladder, bowel, gross motor function and ambulation, but fine motor skills may remain impaired. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS BLUNT TRAUMATIC POSTERIOR CORD SYNDROME Article 11 May

2022 DUAL LESION SPINAL CORD INJURY IN A POLYTRAUMA PATIENT: A CASE REPORT Article 30 September 2021 RETAINED BULLET IN THE CERVICAL SPINAL CANAL AND THE ASSOCIATED SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

CONUNDRUM: CASE REPORT AND REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE Article 21 August 2020 INTRODUCTION Central Cord Syndrome (CCS) is the most common of the spinal cord injury syndromes. It accounts for

9.2% of all spinal cord injuries and affects mainly the older population with an average age of 53 years.1 It was initially described by Schneider _et al._2 in 1954 as a tetraparesis that is

more severe in the upper extremities (forearms and hands) than in the lower extremities. Bladder dysfunction, usually urinary retention, and variable sensory impairment below the level of

injury are also associated. The lower extremities tend to recover motor power first, bladder function returns next and finally strength in the upper extremities reappears, with the finer

finger movements coming back last. Few cases have been presented with gunshot wound (GSW) as a cause of a central cord syndrome, and none, to our knowledge, has been presented without any

evidence of central canal bullet/bone fragments.3–6 It is our intention to present a case with this cause and review the literature available. CASE Our patient is a 27-year-old male who

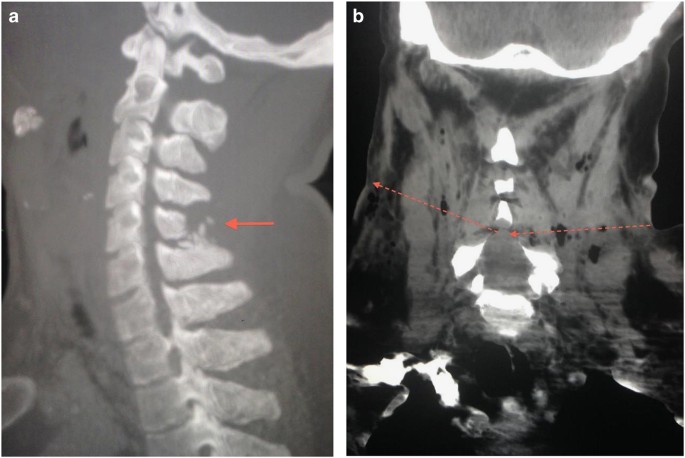

suffered two close-range gunshot wounds (GSW) fired by a handgun, one to the left neck and one to the left shoulder. Computed tomography (CT) of the neck showed C5 spinous process comminuted

fracture and posterior paraspinal muscle hemorrhage without evidence of central canal stenosis or bullet/bone fragments (Figure 1). He also had left proximal humeral comminuted diaphyseal

fracture. Physical examination showed severe weakness, nonspecific dysesthesias and hyperesthesias in bilateral upper extremities more on left side. There was also mild weakness in bilateral

lower extremities, mostly proximally on hip flexors. No side to side differences were noted on pain and temperature sensation. The patient denies any head or facial trauma after falling to

the floor, and there was no evidence of head trauma on physical examination. Diagnosis of central cord syndrome was made and a left brachial plexopathy was suspected, as symptoms were more

prominent on this side and the patient had a proximal humeral fracture. A detailed motor and sensory score according to International Standard Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord

Injury is shown below (Table 1). The patient was classified as AIS D C3 level according to the score. Anal sphincter tone was present as well as sensation. At initial evaluation, the patient

had an indwelling foley catheter; so bladder evaluation was not possible. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study could not be performed due to the presence of a bullet slug on the left

arm. He received conservative management with immobilization, pain medication and inpatient rehabilitation. Although no urologic studies were available, the history data at 2 months show

episodes of incontinence and urgency about twice weekly, suggesting the presence of hyperactive bladder. Bowel had a frequency of every other day controlled with oral laxatives.

Electrodiagnostic study was conducted at 2 months post injury and showed no evidence of brachial plexopathy. At four months post injury, the patient had good recovery with left proximal arm

and bilateral distal hand weakness. His bladder and bowel control had markedly improved, he was no longer using oral laxatives and had fewer incontinence episodes about once or twice a month

with continued urgency and frequency. At 1-year follow-up, he was fully independent in ambulation without assistive device and ADLs. No durable medical equipment was required. He continued

to have mild right-hand weakness and incoordination, and variable dysesthesias not dermatome-specific below the injury level. He had fine motor skill deficits and continued in occupational

therapy. He had normal and controlled bowel function, but hyperactive bladder with fewer frequency and urgency with little to none incontinence episodes. DISCUSSION In the literature

reviewed, we found four cases of CCS caused by GSW to the spine.3–6 In all of the above-mentioned cases, there was radiological or surgical evidence of spinal canal bullet or bone fragments.

The patients developed initial diplegia of the upper extremities or tetraplegia, with a predictable ascending recovery, variable sensory symptoms and a relatively good functional prognosis.

GSW to the spine can cause direct or indirect injuries. Direct injuries result from the bullet nucleus, broken metallic or bone particles and disc material. Indirect injuries result from

the hydrodynamic strike effect (blast wave or cavitation wave) that cause damage distant to the projectile trajectory. Other factors may influence the severity of the injury. The bullet

pathway yaws or tumbles and can cause increased damage. The bullet size and the proximity of the firearm to the target influence the damage. The nearer the firearm is to the target, the more

damage it causes also associated to tearing and burning from gunpowder.7 In our patient, only a fractured C5 spinous process was observed with no evidence of spinal stenosis, instability or

intracanal fragments. Although an MRI was not performed, the CT scan showed sufficient evidence to guide management. Further evaluation with electrodiagnostic study ruled out other causes

of upper extremity weakness such as radiculopathy or plexopathy. Patient’s management and outcome was in accordance to the reviewed literature. Diagnosis of CCS with a stable, nonprogressive

injury was established, and conservative management with aggressive rehab was followed. At 1-year follow-up, the patient showed full independence with minor deficits consistent with the

proposed prognosis of most CCS. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY Although still controversial, the pathophysiology of CCS was attributed to the geographical arrangement of the lateral corticospinal tracts

that extend from the brain. It was theorized that this motor pathway has the cervical laminations arranged more centrally and the sacral laminations arranged more peripherally, and that

central cord hemorrhage and necrosis was the cause of the disease. Recent studies with MRI and autopsy evidence have not been consistent with the proposed mechanism of central cord

hemorrhage.2,8–10 The classic mechanism of injury described results in a traumatic hyperextension of an already stenotic cervical spine. This hyperextension causes distraction of the

anterior elements (anterior longitudinal ligament, intervertebral disk, posterior longitudinal ligament) and compression of the posterior elements (ligamentum flavum) ultimately pinching the

spinal cord.2,8–10 DIAGNOSIS CLINICAL CCS is mainly a clinical diagnosis. Clinical criteria for CCS were clearly defined almost 60 years ago by Schneider _et al._2 The patient should

present with a spinal cord injury and weakness more prominent in the upper extremities than in the lower extremities. Pouw _et al._,11 with 312 cases of traumatic CCS, describe a more

objective diagnostic criteria with an average ASIA Motor Score difference of 10 points less in the upper extremities than in the lower extremities. A novel classification system, the Central

Cord Injury Scale (CCIS), has been proposed. Its purpose is to provide diagnostic criteria that can aid in the prediction of a possible functional outcome. It focuses on two predictive

factors: ASIA Motor Score and MRI findings, which can help determine the probability that patients have to achieve goals, like walking, without ever using a wheelchair, independent bladder

function and independent bowel function.12 IMAGING No definitive imaging criteria exist for the diagnosis of CCS. CT and MRI can aid in determining the further management of the patient by

identifying important structural and biomechanical factors such as level of injury, instability of the spine and degree of cord compression. Evaluation of these factors can determine the

need for urgent surgical decompression or fixation of an unstable spine.10 MRI evaluation of patients with GSW to the spine is controversial. There may be magnetic pulling of the bullet

fragments that can migrate and cause further tissue injury. Finitsis _et al._13 reported on 19 cases with GSW to the spine where MRI was done and none of the patients experienced adverse

effects or migration of the bullet fragments. Three of these 19 patients underwent surgical intervention as a consequence of the results obtained on the MRIs. Bono & Heary in their

systematic review on GSW to the spine report that in their experience, the most common complaint from patients undergoing MRI scans is a complaint of a heat sensation in the area of the

bullet (particularly jacketed types), which can lead to discomfort and early abortion of the study.14 The information obtained from an MRI, especially details about the spinal cord, are

difficult to obtain from any other imaging source. Risks and benefits should be weighted before performing an MRI in patients with GSW to the spine. TREATMENT NONSURGICAL In the initial

description of CCS by Schneider _et al._,2 it was emphasized that surgical intervention was not necessary in these patients and that the natural course of the disease shows a good prognosis

and if recovery occurs, it should follow a definite pattern. Nonsurgical management consists of immediate immobilization with a hard cervical orthosis after diagnosis of a cervical spinal

cord injury. If no spine instability is seen on imaging studies, the orthosis should be used for at least 6 weeks or when neck pain has resolved with associated neurological improvement.

Rehabilitation focusing on retraining hand function and ambulation are the main goals.9 STEROIDS Although the use of steroids became a standard of therapy after the Second National Acute

Spinal Cord Injury Study (NASCIS II) in 1990,15 it has been greatly debated in the more recent literature. Current neurosurgery guidelines published in 2013 DO NOT recommend the use of

methylprednisolone for the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. There is no Class I or Class II medical evidence supporting the clinical benefit of MP in the treatment of acute SCI.

However, Class I, II and III evidence exists that high-dose steroids are associated with harmful side effects.16 ANTIBIOTICS Risk of infection after gunshot wound to the spine is higher in

the lumbar spine than in the cervical or thoracic area. This is mostly associated to perforation of hollow viscus prior to reaching the spine. Tetanus and broad-spectrum antibiotic

prophylaxis should be considered initially at least in the first 24 h. Bullet extraction has not proven to decrease the risk of septic complications and may be associated to other

complications related to surgery.7,14 SURGICAL MANAGEMENT Several algorithms have been proposed to aid in the decision of performing a surgical intervention in patients with GSW to the spine

(Figure 2). It appears to be a consensus that spinal instability is an absolute indication for surgery, regardless of the severity of injury (complete or incomplete). The definition of

instability in patients with GSW to the spine cannot be extrapolated from the Denis’ Three Column theory for blunt trauma. In GSW patients, the column remains a stationary object and the

bullet is the directional force. This concept is compared with a magician who pulls the tablecloth and the glasses and plates stay in place. Damage to either two or even three columns may

result in a stable spine.14 Spinal instability can be present in any abnormal angulation or translation and in cases where the bullet traverses the pedicle or the facet.7,14,17 Progressive

neurological deficit, cerebrospinal fluid leak and evidence of lead toxicity are also complications in which surgical intervention is strongly recommended. Level of lesion (cervical,

thoracic and lumbar), severity of injury, or the presence of intracanal bullet fragments show varying opinions in the literature reviewed. A trend was noted toward surgical management of

lumbar or cauda equina injuries and nonsurgical/observation of complete injuries.7,14,17,18 CONCLUSION CCS is a common presentation in patients with spinal cord injury, although not commonly

seen in patients who suffered GSW to the spine. Some suggested algorithms exist regarding the management of these patients, but still cases should be individualized depending on the

specific nature of their presentation. It seems to be in general consensus that steroids are not recommended for these patients and that instability of the spine from pedicle or facet

fracture are an absolute indication for surgery. It has been persistent in the literature reviewed that the prognosis for patients with CCS tends to be favorable in regaining sensory,

bladder, bowel, gross motor function and ambulation, but fine motor skills may remain impaired. REFERENCES * McKinley W, Santos K, Meade M, Brooke K . Incidence and outcomes of spinal cord

injury clinical syndromes. _J Spinal Cord Med_ 2007; 30: 215–224. Article Google Scholar * Schneider RC, Cherry G, Pantek H . The syndrome of acute central cervical spinal cord injury. _J

Neurosurg_ 1954; 11: 546–577. Article CAS Google Scholar * Steudel WI, Ingunza W . The syndrome of acute central cervical spinal cord injury after a gunshot lesion. _J Neurosurg_ 1977;

47: 290–292. Article CAS Google Scholar * Mortara RW, Flanagan M . Acute central cervical spinal cord syndrome caused by missile injury. _Neurosurgery_ 1980; 6: 176–180. Article CAS

Google Scholar * Hubschmann OR, Krieger AJ, Lax F, Ruzicka PO, Zimmer AE . Syndrome of intramedullary gunshot wound with incomplete neurologic deficit: case report. _J Trauma_ 1988; 28:

1600–1602. Article CAS Google Scholar * Hatzakis M, Bryce N, Marino R . Cruciate paralysis, hypothesis for injury and recovery. _Spinal Cord_ 2000; 38: 120–125. Article Google Scholar *

Jaiswal M, Mittal RS . Concept of gunshot wound spine. _Asian Spine J_ 2013; 7: 359. Article Google Scholar * Harrop JS, Sharan A, Ratliff J . Central cord injury: pathophysiology,

management, and outcomes. _Spine J_ 2006; 6: S198–S206. Article Google Scholar * Nowak DD, Lee JK, Gelb DE, Poelstra KA, Ludwig SC . Central cord syndrome. _J Am Acad Orthop Surg_ 2009;

17: 756–765. Article Google Scholar * Aarabi B, Hadley MN, Dhall SS, Gelb DE, Hurlbert RJ, Rozzelle CJ et al. Management of acute traumatic central cord syndrome (ATCCS). _Neurosurgery_

2013; 72: 195–204. Article Google Scholar * Pouw MH, Van Middendorp JJ, Van Kampen A, Hirschfeld S, Veth RPH, Curt A et al. Diagnostic criteria of traumatic central cord syndrome. Part 1:

a systematic review of clinical descriptors and scores. _Spinal Cord_ 2010; 48: 652–656. Article CAS Google Scholar * Hohl JB, Lee JY, Horton JA, Rihn JA . A Novel classification system

for traumatic central cord syndrome. _Spine_ 2010; 35: E238–E243. Article Google Scholar * Finitsis SN, Falcone S, Green BA . MR of the spine in the presence of metallic bullet fragments:

is the benefit worth the risk? _Am J Neuroradiol_ 1999; 20: 354–356. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bono CM, Heary RF . Gunshot wounds to the spine. _Spine J_ 2004; 4: 230–240. Article

Google Scholar * Randomized A . Controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. _N Engl J Med_ 1990; 323: 1207–1209. Article Google Scholar

* Hurlbert RJ, Hadley MN, Walters BC, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, Gelb DE et al. Pharmacological therapy for acute spinal cord injury. _Neurosurgery_ 2013; 72: 93–105. Article Google Scholar *

Klimo P, Ragel BT, Rosner M, Gluf W, Mccafferty R . Can surgery improve neurological function in penetrating spinal injury? a review of the military and civilian literature and treatment

recommendations for military neurosurgeons. _Neurosurgical FOCUS_ 2010; 28: E4. Article Google Scholar * Kumar A, Pandey PN, Ghani A, Jaiswal G . Penetrating spinal injuries and their

management. _J Craniovertebr Junction Spine_ 2011; 2: 57. Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Editorial support in this publication was provided by the

National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 2U54MD007587. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and

does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation,

University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston—McGovern Medical School, Houston, TX, USA, Juan Galloza * Department of Physical Medicine, Rehabilitation and Sports Health, University

of Puerto Rico—School of Medicine, Rico, PR, USA, Juan Valentin & Edwardo Ramos Authors * Juan Galloza View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Juan Valentin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Edwardo Ramos View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Juan Galloza. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no conflict of interest. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS

Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Galloza, J., Valentin, J. & Ramos, E. Central cord syndrome from blast injury after gunshot wound to the spine: a case

report and a review of the literature. _Spinal Cord Ser Cases_ 3, 17003 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2017.3 Download citation * Received: 21 February 2016 * Revised: 27 September

2016 * Accepted: 03 January 2017 * Published: 16 March 2017 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/scsandc.2017.3 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read

this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative