- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Cellulases catalyze the hydrolysis of cellulose. Improving their catalytic efficiency is a long-standing goal in biotechnology given the interest in lignocellulosic biomass

decomposition. Although methods based on sequence alteration exist, improving cellulases is still a challenge. Here we show that Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction can “resurrect” efficient

cellulases. This technique reconstructs enzymes from extinct organisms that lived in the harsh environments of ancient Earth. We obtain ancestral bacterial endoglucanases from the late

Archean eon that efficiently work in a broad range of temperatures (30–90 °C), pH values (4–10). The oldest enzyme (~2800 million years) processes different lignocellulosic substrates,

showing processive activity and doubling the activity of modern enzymes in some conditions. We solve its crystal structure to 1.45 Å which, together with molecular dynamics simulations,

uncovers key features underlying its activity. This ancestral endoglucanase shows good synergy in combination with other lignocellulosic enzymes as well as when integrated into a bacterial

cellulosome. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PROKARYOTIC CELLULASE GENE CLUSTERS DERIVED FROM 2,305 METAGENOMES Article Open access 05 February 2025 A METAGENOMIC ‘DARK MATTER’ ENZYME

CATALYSES OXIDATIVE CELLULOSE CONVERSION Article Open access 12 February 2025 ENHANCED CRYSTALLINE CELLULOSE DEGRADATION BY A NOVEL METAGENOME-DERIVED CELLULASE ENZYME Article Open access

12 April 2024 INTRODUCTION Cellulose is one of the major components in plant cell walls and is the most abundant organic polymer on the planet1. This widespread substrate offers a great

opportunity to generate bioproducts, such as biofuels and nanocellulose. There is an enormous variety of raw materials rich in cellulose, such as agricultural, industrial, and urban wastes

that can be used as sources for cellulose2,3. However, generating bioproducts from cellulose is still complex and expensive. Cellulose is a highly recalcitrant substrate difficult to obtain

from plant cell walls, because it is protected by hemicellulose and lignin. In many processes, cellulases must withstand the harsh conditions of the industrial bioconversion process, such as

high temperature, generally above 50 °C, and low or high pH4,5. The lower efficiency of the enzymes under these conditions makes the saccharification process a critical bottleneck in the

bioconversion of cellulose. Increasing the thermal operability and activity of cellulases is perhaps the most investigated aspect for their industrial implementation6,7. In order to improve

cellulases, several strategies ranging from rational and computational design to de novo enzyme design and directed evolution have been implemented, aimed at obtaining biocatalysts with

improved performance5,8,9. Despite these advances, the limitations of engineered cellulases under the highly demanding industrial conditions (in terms of pH, temperatures, the presence of

nonconventional media, and more) are still a barrier that must be overcome. The natural trade-off between activity and stability of proteins makes extremely complicated to enhance, for

instance, the temperature and pH operability, the expression level or the activity of enzymes, all or at least some of them at once. The development of a strategy capable of finding more

suitable blueprints, whereby improving the catalytic properties of enzymes in a cost-efficient manner, may revolutionize the biotechnology and chemical industries. In the past decade or so,

the so-called ancestral sequence resurrection technique (ASR) has been used to study the evolution of genes and proteins10,11,12. ASR utilizes sequences of proteins or genes from different

species to create phylogenetic relationships, from which the sequences of their ancestors can be predicted and reconstructed in the laboratory13. Using a diverse combination of sequences, it

is even possible to reconstruct Precambrian proteins belonging to organisms that lived shortly after the origin of life10,11. Reconstructed ancestral proteins have displayed enhanced

thermal or mechanical stability, better pH response, improved activity and expression level, chemical promiscuity, and in some cases, all of these at once10,11,12,14. These traits are

thought to reflect the conditions in which these ancestral proteins lived. Nevertheless, the molecular bases behind the high efficiency of ancestral enzymes are not fully understood. In

addition, ancestral enzymes have been suggested to work like a “Swiss army knife” due to their versatility, provided that primitive cells likely relied on a limited but efficient set of

enzymes that worked as generalists rather than as specialists15. Precambrian enzymes from the Hadean and Archean eons (older than 2500 million years) were adapted to work under temperature,

pH, and environmental conditions that often resemble those of industrial settings11. Following this assumption, we propose ASR as a paleoenzymology method to generate efficient enzymes

beyond the evolutionary implications. In this work, we test the ability of ASR to generate efficient enzymes by reconstructing ancestral endoglucanases (EG) from ~1.7- to

2.8-billion-year-old bacterial species. The ancestral EGs showed higher activity than those of contemporary EGs under a broad range of temperatures and pH. The oldest enzyme works well with

various substrates even displaying processive endoglucanase and exoglucanase activity. The ancestral EG enzyme also displays higher efficiency when integrated into a bacterial cellulosome, a

macromolecular machine for cellulose degradation16, which has been also proposed for industrial implementation8,17. To investigate the determinants of its activity, we solve the crystal

structure to 1.45 Å, demonstrating that the fold is highly conserved. Interestingly, using the solved structure, we perform atomistic molecular dynamics simulations (MD) in the presence of

substrate, which suggest that the balance between accessibility and dynamics of the substrate on the enzyme active site seems to play an important role on the high efficiency of the

ancestral endoglucanase. Surprisingly, we determine that an efficient bioconversion can be potentially achieved by reconstructing very few enzymes as compared with other methodologies, where

hundreds of variants need to be tested. This work represents a proof of concept, which may open new avenues toward efficient enzyme improvement in a single step. RESULTS ANCESTRAL SEQUENCE

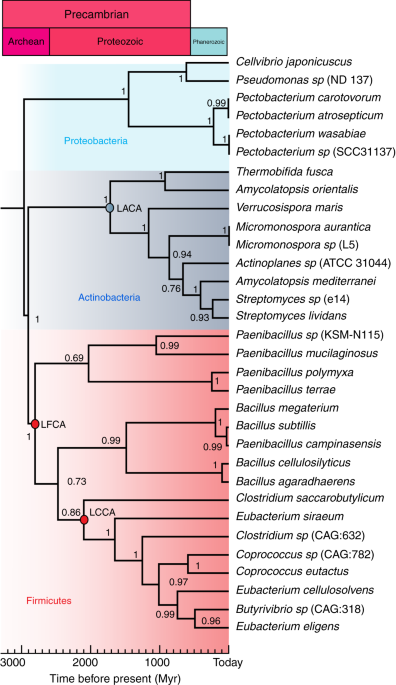

RECONSTRUCTION OF BACTERIAL EG To generate ancestral sequences of bacterial EG enzymes, we use 32 EG Cel5A sequences from extant bacteria (see the ID list of extant sequences in

Supplementary Note 1), which are obtained from the UniProt database (www.uniprot.org), using the sequence form _Bacillus subtilis_ (Bs_EG) as query. We target EG from family Cel5A because of

their interest in biotechnology industry. EG enzymes are present in different bacterial phyla, such as Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria, which diverged more than 3 billion

years ago (~3000 million years ago), indicating that these enzymes are ancient and were present in organisms that lived in the Archean eon. We select sequences from these three phyla. A

sequence alignment is generated, and the catalytic domains of all the sequences are well resolved, forming a block with no major gaps or unstructured portions. In contrast, the

carbohydrate-binding module (CBM), a smaller subunit responsible for cellulose binding, does not align well, as some sequences had the CBM at the C terminus, while others have it at the N

terminus, and there are numerous gaps. In addition, not all the sequences contain a CBM. As the CBM is poorly aligned, we conclude that this module is heterogeneous and poorly conserved

within the family 5 of cellulases. Therefore, we focus on the catalytic region. Using the block of catalytic domains, we construct a phylogenetic chronogram using Bayesian inference18, in

which the three bacterial phyla are well resolved (Fig. 1). We date the phylogenetic tree using data from the Time Tree of Life (TTOL)19. Using the alignment and tree, we reconstruct the

most likely ancestral sequence for each node. We select three nodes, the oldest node belonging to the last Firmicutes common ancestor (LFCA) that lived ~2.8 billion years ago. We speculate

that this may have been one of the earliest cellulase enzymes. This is consistent with the idea that the earliest cellulose producers were likely bacteria before the endosymbiotic transfer

of cellulose synthase to eukaryotic plant cells20. The second node belongs to the last Clostridia common ancestor (LCCA), which is ~2.1 billion years old; the third one from the last

Actinobacteria common ancestor (LACA), ~1.7 billion years old. The ancestral reconstruction utilizes a maximum-likelihood assignment at each site for the residue, with the highest posterior

probability. The posterior probabilities of all 297 sites are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. The average posterior probability values are 0.91–0.99, which ensures reliability of the

reconstruction. Overall, the ancestral sequences display between 50% and 73% identity with respect to the modern Bs-EG. The mutations in the ancestral sequences with respect to the modern

Bs_EG are distributed all over the sequence (Supplementary Fig. 2). To reconstruct the ancestral EGs, the gene sequences of the domains are synthesized and cloned into an expression vector

and expressed in the _E. coli_ strain BL21 (DE3). The ancestral EG enzymes demonstrate a high level of expression, as shown by SDS/PAGE for LFCA_EG (Supplementary Fig. 3). The reason behind

this high expression level is unknown, but it seems to be a common feature among ancestral proteins. ENDOGLUCANASE ACTIVITY MEASUREMENTS To test the performance of the ancestral enzymes, we

carry out activity assays under different conditions. We first test enzyme activity in the temperature range 30–90 °C and compare the activity of the reconstructed enzymes with those of

contemporary enzymes from _Thermotoga maritima_ (Tm_EG) and Bs_EG, at the same temperatures. Both enzymes belong to the Glycoside Hydrolase Family 5 (GH5). Tm_EG is interesting because _T.

maritima_ is a hyperthermophilic organism that lives at temperatures up to 90 °C; _T. maritima_ is one of the most extremophile bacteria known today. The thermal range tested is broader that

the typical testing range, which normally covers from 40 to 70 °C. We first use a standard soluble substrate such as carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), using the dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS)

assay to assess the release of reducing sugars by EGs21. The oldest ancestral LFCA_EG and LCCA_EG shows higher activity than the modern enzymes, with soluble CMC at all temperatures until 70

°C. At 80 and 90 °C, the activity of these enzymes is similar to that of the hyperthermophile Tm_EG (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, such high operational temperature has only been achieved by

contemporary archaeal cellulases7. Another important factor in cellulose hydrolysis is the pH at which the reaction is carried out. The pretreatment of lignocellulosic material can be

performed at low or high pH values22. Therefore, improving cellulase activity in a broad range of pH values is of interest from an industrial point of view, as it would minimize the need for

neutralization and the associated cost. We determine the activity of the reconstructed cellulases from pH 4 to 10 at 50 °C using CMC. LFCA_EG and LCCA_EG show the highest activities (Fig.

2b). We find that the younger LACA_EG performs like Tm_EG. From the temperature profiles in Fig. 2a, we wonder whether any evolutionary trend can be devised. We plot the relative activity of

the ancestral enzymes plus Bs_Eg against the evolutionary time and a clear decreasing trend can be observed (Fig. 2c). We do this at 50 °C, but the same is true for most temperatures.

Surprisingly, this trend runs parallel to the cooling trend of seawater temperature over the past 3.5 By, as determined from δ18O in marine cherts23, which suggests that enzyme stability,

activity, and environmental temperature are all linked. This trend seems to be general in ancestral protein stability24,25, but we prove it here for activity. From the three ancestral

enzymes, we take the most efficient one, i.e., LFCA_EG, for further experimental testing. We study the kinetics of the enzymatic reaction for the studied cellulases by applying the

Michaelis–Menten model. From the experimental data in Fig. 2c, we determine that the _K_M, a measure of affinity, is quite similar for the three enzymes although slightly lower for LFCA_EG

(1.25 mg mL−1). The highest turnover rate, _k_cat, corresponds to the ancestral LFCA_EG (0.04 s−1). Similarly, the highest catalytic efficiency, _k_cat/_K_M, is also achieved by LFCA_EG

(0.032 mL mg−1 s−1), doubling the value of the modern enzymes. The kinetic parameters determined from the plot are shown in Table 1. Overall, these parameters indicate that LFCA_EG shows a

higher substrate affinity, is faster, and more efficient that the modern enzymes. We also evaluate how stable to temperature incubation is the ancestral EG, compared with Tm_EG and Bs_EG. We

determine the _T_50 value (defined as the temperature at which the enzyme loses half of its activity after 30 min of incubation). _T_50 values of 85, 79, and 68 °C are obtained for Tm_EG,

LFCA_EG, and Bs_EG, respectively. The activity is determined at 60 °C after the incubation (Fig. 2d). The ancestral EG was performed short behind the extremophile Tm_EG, highlighting its

thermophilic nature. Apart from their resistance to temperature and pH, ancestral enzymes have been suggested to show chemical promiscuity, which might be reflected in the ability to operate

over more than one substrate or in the ability to display more than one mechanism of action14. An interesting promiscuous behavior in EG is to display processive activity, that is, to show

both endoglucanase and exoglucanase activity. This is typical for EG from family GH9. We decide to test our LFCA_EG for such processive activity by measuring the relation between soluble and

insoluble sugars in the reaction. Surprisingly, LFCA_EG shows a higher ratio of soluble to insoluble sugars after 30 min of incubation, as compared with Tm_EG and Bs_EG that remain nearly

constant at all times (Fig. 2e). The measured ratio for LFCA_EG is similar to that of other natural or designed EG with processive activity26. Although some hydrolases from family GH5 have

been shown to be processive27, they have not been included in our phylogeny, which makes the processivity of the ancestral LFCA_EG a surprising feature. Besides bacterial cellulase, we also

test our LFCA_EG against a fungal EG, given that fungal EG is much widely used than bacterial ones in biotechnological applications. We compare LFCA_EG with endoglucanase from _Trichoderma

reesei_ from family Cel5A (Tr_EG). From the activity experiments, we still observe that the ancestral LFCA_EG shows better performance in most conditions tested (Supplementary Fig. 4 and

Supplementary Table 1). This result shows that designer bacterial EGs might be a good alternative to fungal ones, due to their diversity, complexity, thermal and pH operability, and even

higher activity, as well as the high growth rate of bacteria8. However, the high performance of LFCA_EG is not only limited to a soluble laboratory substrate such as CMC. In industry, the

actual interest resides on the hydrolysis of crystalline cellulose28. For this reason, we compare the activity of the EG enzymes using a microcrystalline substrate such as Avicel. Avicel

requires long digestion times. We perform the assay at different times ranging from 4 to 72 h. For the assay, we use LFCA_EG in two forms, only the catalytic domain and the catalytic domain

incorporating a CBM from _Clostridium_ _thermocellum_, since an ancestral CBM cannot be reconstructed, as we have discussed. From Fig. 3a, we can observe that the maximum conversion

percentage corresponds to the LFCA_EG form incorporating the CBM, but it is also surprising that the LFCA_EG catalytic domain by itself also displays remarkable activity against Avicel. The

conversion at 70 h of hydrolysis reaches 60% for LFCA_EG with CBM, 45% for LFCA_EG, and around 25% for Tm_EG and Bs_EG, at equal enzyme load. Importantly, for industrial applications,

cellulases must be able to hydrolyze cellulose in lignocellulosic materials, such as agricultural, industrial, or the organic fraction of city waste, in which cellulose in crystalline and

amorphous forms together with lignin and hemicellulose is present. The digestion occurs in synergy with other enzymes, such as laccase and hemicellulases that given the recalcitrant nature

of the biomass, helps by breaking down lignin and hemicellulose, making cellulase accessible for hydrolysis. This is important, for instance, for the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass,

using enzymes for biofuel production. To test this aspect, we use cardboard, newspaper, and softwood from pine tree as a source of cellulose. These three materials have different contents

of cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose. While cardboard contains around 60% cellulose and around 15% of lignin and hemicellulose, newspaper and pine softwood contain less cellulose, 50% or

less29,30, and more lignin, ~22% and ~30%, respectively, and ~18% and ~25% of hemicellulose, respectively. We perform activity assays using isolated LFCA_EG and in combination with an

evolved laccase mutant from _Myceliophthora thermophila_31 and xylanase from _Trichoderma viride_ (_endo_-1,4-_β_-xylanase M1), enzymes that can help to break down lignin and hemicellulose,

respectively. We determine the percentage of cellulose hydrolyzed in a 50 mg sample of lignocellulosic material29,30, within 1 h at 50 °C and pH 4.8. In the case of cardboard, the three EG

enzymes degrade very small amounts of cellulose on their own, no more than ~19% (Fig. 3b), suggesting that cellulose is not easily accessible. LFCA_EG worked best when used synergistically

with laccase and xylanase, hydrolyzing close to 40% of the cellulose present in the sample, as compared with Bs_EG_, which_ degraded ~27% and Tm_EG, _which_ degraded ~14%. In the case of

newspaper and softwood, similar efficiency of cellulose degradation than cardboard is obtained, although still LFCA_EG shows higher conversion (Fig. 3c, d). These results highlight not only

the potential of LFCA_EG to work with lignocellulosic substrates, but also the advantage of using multienzyme cocktails containing cellulases, laccases, xylanases, and other enzymes for

efficient enzymatic pretreatment of raw materials and subsequent hydrolysis of cellulose. Similar measurements are carried out comparing LFCA_EG with Tr_EG, in which LFCA_EG also

demonstrates better performance (Supplementary Fig. 5). INTRODUCTION OF THE LFCA_EG IN A CELLULOSOME Another attempt to increase the activity of LFCA_EG is to incorporate it into scaffoldin,

a non-catalytic scaffolding protein from a cellulosome, which is a macromolecular complex containing several lignocellulose-degrading enzymes anchored via dockerin protein domains.

Anaerobic cellulolytic bacteria such as _C. thermocellum_ utilize the cellulosome to degrade cellulose very efficiently, and its use has been suggested for industrial applications, due to

the increased cellulolytic activity observed when compared with the free enzymes32. We make different constructs fusing EG enzymes to dockerin domains present in this cellulosome to convert

LFCA_EG into the cellulosomal mode. We fuse dockerin at the C terminus of the ancestral EG (LFCA-Dock) to allow its incorporation into a mini-scaffoldin containing a single (Scaf1) or two

tandem (Scaf2) cohesin modules (Fig. 4a). As controls, we use LFCA EG (LFCA-Dock) fused to a cellulose-binding module (LFCA-CBM) and _C. thermocellum_ Cel8A EG (CtCel8A), a major EG in its

cellulosome33. LFCA-Dock incorporation into two mini-scaffoldins occurs at molar ratios of 1.1:1 (LFCA-Dock:Scaf1) and 2:1 (LFCA-Dock:Scaf2), which is close to the expected ratio since

cohesin–dockerin-binding occurs in a 1:1 ratio32, indicating precise complex formation (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, LFCA-Dock incorporated into the cellulosome and LFCA_EG-CBM is capable of

binding microcrystalline cellulose Avicel (Supplementary Fig. 6), while the other proteins fail. This indicates that, as expected, only when a CBM is present, specific microcrystalline

cellulose binding can occur. To study the effect of the incorporation of LFCA_EG into the cellulosome, we first perform activity assays with Avicel, which is targeted by the CBM used (Fig.

4c). According to the thermal stability measurements, we perform these assays at 70 °C, a temperature at which no major loss of activity is expected to occur during the long incubation time

needed. Free LFCA_EG shows higher activity with this substrate than native CtCel8A (4.3 ± 0.2 vs. 2.9 ± 0.13 mmol sugars mmol−1 enzyme min−1, respectively). Dockerin incorporation into

LFCA_EG results in a lower activity (3.41 ± 0.03 mmol sugars mmol−1 enzyme min−1) than that of the original LFCA_EG, which is still slightly higher than that of CtCel8A (Fig. 4c).

Importantly, when LFCA_EG-Dock is incorporated into Scaf1, the resulting activity is remarkably enhanced, 6.2 ± 0.7 mmol sugars mmol−1 enzyme min−1, with a high degree of synergy of 1.8 ±

0.2 (defined as the ratio of the activity of the bound enzyme over that of the free one). In the case of CtCel8A, the activity measured is 4.2 ± 0.7 mmol sugars mmol−1 enzyme min−1 in the

presence of Scaf1 and a degree of synergy of 1.4 ± 0.3 was found. The complex LFCA_EG-CBM shows a similar activity than that of LFCA-Dock, 7.0 ± 0.3 mmol sugars mmol−1 enzyme min−1,

supporting the idea that this enhancement is due to a substrate-targeting effect. Incorporation into Scaf2, whereby two tandem identical cohesins allow for the formation of a cellulosome

with two enzymes, does not provide further activity enhancement in either case, 4.4 ± 1.8 for LFCA_EG and 4.3 ± 0.6 mmol sugars mmol−1 enzyme min−1 for CtCel8A. Nevertheless, this result

does not preclude the possibility of further synergy, if different enzymes are used in the future, together with LFCA_EG. Similar results are observed at all of the tested pH values

(Supplementary Fig. 7) and at lower temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 8). However, at temperatures above 80 °C, the situation is reversed and CtCel8A shows higher activities (Supplementary

Fig. 8), perhaps due to the long reaction times. The activity of the different proteins and complexes is then tested for different substrates to investigate the origin of the enhanced

activity upon cellulosomal incorporation. First, we use PASC (Fig. 4d), an amorphous cellulose substrate. The results obtained are similar to those presented for Avicel, where LFCA_EG shows

higher activity than CtCel8A when studied free in solution. Incorporation of both enzymes into Scaf1 resulted in an increased activity, which is higher for LFCA-containing mini-cellulosomes

than in CtCel8A ones. However, when tested on CMC, to which the CBM used in this study does not bind, neither the fusion with dockerin or the CBM fusion, nor the integration into a

mini-cellulosome, significantly alters the activity of LFCA_EG or CtCel8A (Fig. 4e). Since the CBM used in this study is expected to bind PASC but not CMC, the results obtained also support

the idea that scaffoldin CBM is capable of further enhancing the activity of LFCA_EG on certain substrates. Importantly, the activity of LFCA_EG is found to be greater than that of CtCel8A

in all substrates, although these results seem to depend on the particular conditions of the assay, especially above 70 °C (Supplementary Fig. 8). Taken together, these results indicate that

the incorporation of LFCA_EG into a mini-cellulosome enhances its activity, especially for substrates that are difficult to degrade, which are the most interesting ones for biotechnological

applications. COMPARISON OF THE CRYSTAL STRUCTURES OF THE EG The experiments described above show that the ancestral EG is more active than the modern enzymes in almost any condition. To

shed light into the structural basis of this high efficiency, we solve the crystal structure of LFCA_EG to 1.45 Å resolution (PDB ID: 6GJF) from data collected at a synchrotron source. The

crystal belongs to the _P2__1_ space group (Supplementary Table 2) with six polypeptide chains in the asymmetric unit and a water content of 45.5%. All chains present the conserved EG

canonical fold typical for enzymes from the GH5 family, composed of an internal β-barrel surrounded by an array of α-helices, (β/α)8-barrel (Fig. 5a, b). The maximum root mean square

deviation (RMSD) is of 0.34 and 0.28 Å between chains A and C for the Cα and all atoms, respectively. To investigate any substantial structural change, we compare the structure of LFCA_EG

with that of Bs_EG (PDB ID: 3PZT), sharing 73% of their sequence, also used as a query model for the molecular replacement phasing procedure. From the superposition of both structures (Fig.

5c), we see that all major structural elements are equivalent with an all-atom RMSD of 0.5 Å. We do not observe any major difference other than a small displacement, lower than 2.5 Å, in

several loops. A structural alignment of the two enzymes also reveals the location of the conserved and mutated residues (Supplementary Fig. 9). Mutations mainly occur in α-helices and

loops. We also compare the structure of LFCA_EG with that of Tm_EG (PDB ID: 3MMU). The all-atom RMSD is of 2.6 Å, in the best of the cases, which is not surprising since sequence identity

between Tm_EG and our ancestral enzyme is only ~20%. Although all three structural models have similar fold, relevant differences are observed between the ancestral and Tm_EG structures with

significant movement of some secondary elements (Fig. 5d). The internal β-barrel is quite conserved, whereas the outer α-helices show structural changes. There is also relevant displacement

in several loops accumulating the higher sequence discrepancy between both enzymes, with important deletions in the ancestral reconstructed one. Nevertheless, the residues E136 and E224 of

LFCA_EG, essential for the catalytic reaction, are in a similar position than those in Bs_EG and Tm_EG. Also, W174 and W258, that serve for substrate recognition and stacking, are conserved

and equivalent to those of Bs_EG and Tm_EG (Fig. 5e, f). Whether the small structural differences observed can explain the difference in activity is hard to tell. COMPUTER SIMULATIONS FOR

THE EG Computer simulations with atomistic detail can shed light on the origin of the outstanding activity of the ancestral enzyme, particularly for understanding enzyme–substrate

interactions. Crystallizing a cellulase enzyme bind to its glucosidic substrate, without mutating the active site to freeze the substrate, is virtually impossible due to the hydrolyzing

activity of the enzyme. Hence, MD simulations are a good alternative to study the positioning and dynamics of the substrate in the active site prior to the hydrolysis reaction. We use the

experimental structures for the cellulases from Tm_EG, Bs_EG, and LFCA_EG in the presence of a tetrasaccharide (Fig. 6a). Since the experimental structures lack the ligand, we insert it by

fitting each experimental structure onto that of a cellotetraose-bound mutant of Cel5 from _Thermotoga maritima_ (PDB ID: 3AZT) and carefully replacing the substrate for a cellotetraose (see

further details in the “Methods” section). Two independent equilibrium MD simulations are prepared for each complex, with the total simulation data for each enzyme adding up to 1 ms (the

results of one set of simulations are reported in Fig. 6b, while those for the other set are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10). This simulation timescale allows for probing the dynamics of the

ligand within the active site cavity. Although we cannot recover exhaustive sampling with only two runs, our results show important qualitative differences in terms of protein–substrate

interactions for the three enzymes. On the one end, we find that the Tm_EG keeps the substrate closest to the catalysis-competent position, where the nucleophile (E253) and proton donor

(E136) are closest to the glycosidic oxygen, _d_nuc and _d_AB in Fig. 6b plots, respectively (see also Supplementary Fig. 10). This is facilitated by a long loop that forms a clamp for the

substrate (via a tryptophane residue, W210), which is possibly required for efficient binding at the high temperatures where this thermophile grows. In the two simulation runs of the Bs_EG

enzyme with the sugar, we find that the substrate escapes from the binding site, as monitored by the distances of the glycosidic oxygen to the donor and nucleophile glutamic residues (E169

and E257) (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 10), suggesting a lower affinity in good accordance with experiment. In what appears an intermediate situation between Tm_EG and Bs_EG, the

ancestral enzyme LFCA_EG is able to retain the substrate close to the position compatible with catalysis during the full duration of our simulations, albeit with stronger fluctuations than

in the case of Tm_EG. The picture that we recover from the MD simulations is that of a greater retention of the substrate for the Tm_EG enzyme and lower affinity for Bs_EG, with the

ancestral enzyme (LFCA_EG) being somewhere in-between. The greater retention of the substrate in Tm_EG is consistent with its higher degree of active site burial. We show a representation of

the active site cavities for each protein, derived from the CASTp3.0 server34, in Supplementary Fig. 11. Clearly, the Tm_EG has a greater surface area than that of Bs_EG and LFCA_EG, due to

the longer loop encompassing tryptophan W210. This loop may be involved in large-amplitude motions that modulate the access of the substrate and release of the product. Unfortunately, the

MD simulations we perform are too short relative to the timescales in which these movements may occur. For this reason, we derive an elastic network model (ENM), which can efficiently

predict conformational fluctuations related to ligand binding35 (see Supplementary Information). The slow modes from the ENM for Tm_EG predict opening and closing motions that are highly

localized in the loop region (Supplementary Fig. 12). These slow dynamics may hinder ligand binding compared with the very easy access of the substrate to the active site in Bs_EG and

LFCA_EG. We speculate that, for LFCA_EG, the greater ability to retain the substrate relative to Bs_EG together with the easy access to the active site in the opened cavity may contribute to

the increased activity observed in the experiments, providing a “best of both worlds” situation relative to its extant counterparts. In addition, these results provide a clue for the

structural origin of substrate promiscuity. DISCUSSION Numerous ancestral proteins and enzymes have been reconstructed in the past few years, but most of them mainly aim to prove

evolutionary hypotheses. Although the possibility of using ancestral enzymes in biotechnology has been pointed out before14,15,24, such a goal still remained unexplored. Here, we use ASR to

improve an example of an enzyme relevant in biotechnology, and we focus on most of the aspects that are of interest in a possible industrial setting, i.e., thermostability, pH tolerance,

broad substrate usage, chemical promiscuity, and synergy with other enzymes. In this work, we show that an ancient reconstructed endo-_β_-glucanase displays high activity over a broad range

of temperatures, pH values, and substrates, both as a free enzyme, and in combination with other lignocellulosic enzymes, as well as part of a cellulosome complex. This enzyme also shows

processive endoglucanase activity, which is remarkable given that its modern counterparts from family GH5 do not display exoglucanase activity. Overall, the ancestral enzyme displays

chemical properties that make it an interesting catalyst for possible biotechnological and protein engineering applications. From the crystal structure, we can infer that the ancestral EG

maintains the same fold as modern cellulases. Simulating a complete enzymatic reaction would require complex quantum mechanical calculations that are beyond the scope of this work. However,

using the crystal structure, it is possible to run classical MD that can shed light into the structural rearrangement between the enzyme and the substrate prior to the reaction itself. These

simulations show that the ancestral enzyme seems to share features with the other two enzymes studied, on the one hand accommodating the substrate for the whole duration of the simulations

(like in the simulations of Tm_EG), and on the other hand, allowing for greater dynamics in the more opened active site (as is the case of Bs_EG). We speculate that the greater dynamics and

the opened cavity in the active site may contribute to the promiscuity of substrates that is a characteristic feature of ancestral enzymes. A relevant aspect of this new ancestral enzyme is

its elevated activity even at high temperature. Typically, ancestral enzymes are not necessarily more stable than those from modern extremophiles11. Enzymes present in the Hadean and Archean

eons, when the temperature of the oceans was estimated to be 60–70 °C10, were thermophiles11,25,36. This thermophilic phenotype is captured by ASR and exhibited by our ancestral EG.

However, our LFCA_EG goes beyond the thermophilic range, working at 30–90 °C. This range covers a good portion of temperatures from mesothermophiles to hyperthermophiles. However, ancestral

enzymes display other properties, such as broad pH usability, higher expression yields, or substrate and catalytic promiscuity11,14, which makes them stand up vs. extant enzymes, including

extremophiles. These features make ancestral enzymes an interesting alternative for industry. In general, ancestral enzymes are considered to be generalists having a broader range of

applicability than contemporary enzymes, which are considered specialists37, including extremophiles, for which the evolution to substrate and organismal specificity may limit their

efficiency outside their natural environment. Thus, ASR emerges as a potential methodology for protein engineering with multiple applications in biotechnology38,39, beyond its possible

evolutionary implications. Also, it is remarkable that our resurrected EG enzyme works well at 30 °C. This temperature is interesting for future applications in processes, such as

consolidated bioprocessing of biomass, which is carried out to obtain bioethanol in a single step combining saccharification and fermentation40. A single EG enzyme is needed to achieve high

activity under different conditions and substrates, which is difficult for any other protein engineering technique currently available. Certainly, our result could be a valuable departure

point for further EG engineering through directed evolution, which typically starts from modern enzymes of limited evolvability, given that they have been already specialized by natural

selection toward a given function. Indeed, the first successful example of laboratory evolution of a Precambrian enzyme has been reported, opening an unexplored path for more challenging

objectives41. Among them, improving the thermal stability of an enzyme while maintaining its catalytic activity unchanged is a milestone for protein engineers, given the complex

interrelation between structure and function in proteins42. Furthermore, while our ancestral EG is both thermoactive and thermostable, it also shows a noticeable catalytic efficiency.

Finally, the ancestral EG also shows very good synergy with other lignocellulosic enzymes, such as laccase and xylanase, and its activity can be further enhanced by incorporation into the

cellulosomal mode. We anticipate that other lignocellulosic enzymes, including fungal cellulases and ligninases, could benefit from ancestral reconstruction, which could also help to

generate very efficient cocktails for the saccharification step of cellulosic substrates. This would provide a long-awaited improvement that could be used in numerous industrial

applications. METHODS PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS AND ANCESTRAL SEQUENCE RECONSTRUCTION We downloaded 32 endoglucanase sequences from different species divided in three bacterial phyla

(Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Firmicutes) from UniProt database. All sequences belong to the family Cel5A and are classified as 1,4-(1,3:1,4)-_β_-d-glucan-4-glucano-hydrolases (EC

3.2.1.4). All sequence ID numbers are listed in the Supplementary Information. The sequences were aligned using MUSCLE43 software and further edited manually. The alignment was tested for

best model of protein evolution using ProTest44, resulting in the Jones–Taylor–Thornton (JTT), with gamma distribution model as the best evolution model. The phylogeny was performed using

Bayesian inference using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). We used BEAST v1.8.4 package software18 incorporating the BEAGLE library for parallel processing. We set monophyletic groups for

Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Firmicutes. We set the JTT model with eight gamma categories and invariant distribution, Yule model for speciation, and length chain of 25 million

generations, sampling every 1000 generations. We estimated divergence times using the uncorrelated log-normal clock model (UCLN), using molecular information from the TTOL19. Birth and death

rates were set to default. Calculations were run for 2 days in a 12-core iMac computer. We discarded the initial 25% of trees as burn-in using the LogCombiner utility from BEAST. The MCMC

log file was verified using Tracer, with all parameters showing effective sample size (ESS)>100. Tree Annotator was used to estimate maximum clade credibility. All nodes were supported by

posterior probabilities above 0.69, with most of them nearly 1. FigTree v1.4.2 was used for tree representation and editing. Ancestral sequence reconstruction was performed by maximum

likelihood using PAML 4.845, incorporating a gamma distribution for variable replacement rates across sites and the JTT model. Posterior probabilities were calculated for all 20 amino acids.

In each site, the residue with the highest posterior probability was selected. Three internal nodes LFCA, LCCA, and LACA were selected for laboratory resurrection. PROTEIN EXPRESSION AND

PURIFICATION Ancestral LFCA_EG, LCCA_EG, LACA_EG, extant Tm_EG (ID: Q9X273), and Bs_EG (ID: P23549) proteins encoding genes were synthesized and codon-optimized for expression in _E. coli_

cells. They were cloned into pQE80L vector (Qiagen) and transformed onto _E. coli_ BL21 (DE3) (Life Technologies). Cells were incubated in LB medium at 37 °C, and after reaching OD600 of

0.6, IPTG was added to a final solution of 1 mM to induce protein expression overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000 rpm. Cell pellets were resuspended in extraction buffer

containing 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7, 300 mM NaCl, and lysed using a French press. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 40,000 rpm for 40 min. For purification, His6-tagged

proteins were loaded onto His GraviTrap affinity column (GE Healthcare) and eluted in 50 mM sodium-phosphate buffer, pH 7, 300 mM NaCl, and 150 mM imidazole. Finally, proteins were further

purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200HR column (GE Healthcare) and eluted in 50 mM citrate buffer at pH 4.8. For the verification of purified proteins, sodium

dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) was used on 12% gels. The protein concentration was estimated by measuring absorbance at 280 nm using a Nanodrop 2000C. Tr_EG is

a commercial preparation and two different batches were used for the experiments: one as lyophilized powder (Sigma reference C8546 from _T. reesei_ ATCC 26921) and a second one as enzyme

solution from Sigma-Aldrich (C2730), both sold as 1,4-(1,3:1,4)-_β_-d-glucan-4-glucano-hydrolase (EC 3.2.1.4). The determination of the protein concentration in the solution (C2730) was

first made by the dry-weight method46 for protein content determination. Size-exclusion chromatography was used with a Superdex 200HR column and eluted in water. Then the sample was frozen,

dried, and weighted. Protein concentration was also determined by the BCA assay (PierceTM, Thermo Fisher 23227) using a BSA standard supplied with the kit and also our ancestral LFCA_EG. A

total protein concentration of about 125 mg mL−1 was determined with both methodologies. Using Tr_ EG in the powder or solution form provided nearly identical results at the same

concentration. An evolved laccase (KyLO mutant) from _M. thermophila_ was heterologously produced in _Saccharomyces cerevisiae_, as reported elsewhere31. ENZYMATIC ACTIVITY ASSAYS

Cellulolytic activity of ancestral EG was tested in 50 mM citrate buffer, pH 4.8, containing 2% CMC (Sigma-Aldrich reference 21902) for 30 min at various incubation temperatures and a final

volume of 500 µL. Cellulases from Tm_EG and Tr_EG (from Sigma-Aldrich, reference C8546 for lyophilized powder and C2730 for enzyme solution) were used as controls. Enzyme dosage 5 mg per

gram of glucan. Enzymatic reactions were terminated by placing the tubes into an ice-water bath. Enzymatic activity was determined quantitatively by measuring soluble reducing sugars

released from the cellulosic substrate by the DNS method21. All assays were performed in 5% glycerol that is used as a stabilizer. A volume of 1.5 mL of the DNS solution was added to each

sample, and after boiling the reaction mixture for 5 min, absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a NanoDrop 2000C. A glucose standard curve was used to determine the concentration of the

released reducing sugars. All assays were performed in triplicate and the average value with standard deviation was determined. On determination of the pH dependence, purified enzymes were

diluted in 50 mM citrate buffer at different pH values between 4 and 10; citrate buffer for pH 4 and 5, phosphate buffer for pH 6, 7, and 8, and carbonate buffer for pH 9 and 10. Activities

were measured with 2% CMC at 70 °C for 30 min. The amount of reducing sugars was measured and quantified by the DNS and BCA methods. Avicel (Sigma-Aldrich Ref S3504) was used for the

determination of the enzymatic activity in crystalline substrates. A volume of 0.4 mL of enzyme solution was placed together with 1.6 mL of 1.25% Avicel solution. Enzyme dosage 15 mg/g of

glucan. Substrate and enzymes blanks were also prepared. Enzymatic reactions were stopped by placing the tubes into an ice-water bath, and the tubes were then centrifuged for 2 min at 14,000

rpm at room temperature. Enzymatic activity was determined quantitatively by measuring soluble reducing sugars released from the cellulosic substrate by the DNS. A volume of 1.50 mL of the

DNS solution was added to 1 mL of sample (supernatant fluids), and after boiling the reaction mixture for 5 min, absorbance at 540 nm was measured. KINETIC PARAMETERS DETERMINATION To

determine the kinetics parameters of the cellulases, _K_M and _V_max, numerous substrate concentrations were used in the range of 1–20 mg mL−1 of CMC for measurement of endoglucanase

activity. The _K_M and _V_max were determined directly from the linearized fitting of the Michaelis–Menten model, generated using Phyton in-house written script. _k_cat was determined from

the relation _V_max/_E_t, where _E_t is the total enzyme concentration in μmol mL−147. The parameters are reported in the main text and Table 1. PROCESSIVITY ASSAY In order to determine the

processivity26 of the cellulases, there was a ratio of soluble to insoluble reducing sugar from PASC. The reaction was carried out at 45 °C with 0.5% of PASC, and a sample was removed from

the mixture at different time points. After centrifugation, the quantity of the released reducing sugars in the supernatant and in the remaining PASC fraction was determined by the DNS

method. LIGNOCELLULOSIC SUBSTRATES HYDROLYSIS We used 50 mg of milled lignocellulosic material (cardboard, newspaper, and pine softwood) in 50 mM citrate buffer at pH 4.8. Enzyme hydrolysis

was performed for 1 h at 50 °C. Endoglucanase alone or in combination with laccase and xylanase was used for hydrolysis of the lignocellulosic material. Three different enzyme combinations

were used differing in the endoglucanase used: LFCA_EG, Tm_EG, Bs_EG, and Tr_EG. EG enzyme dosage was 14 mg/g of cellulose in the case of cardboard and 15 mg/g of cellulose in the case of

newspaper and softwood, 50 µL of a solution of ~4 U mL−1 of laccase, and 5 µL of a solution of ~1700 U mL−1 of xylanase (_endo_-1,4-β-xylanase M1 from _Trichoderma viride_, Megazyme) in a

total volume of 500 µL. Released sugars are quantified with the DNS method. Cellulose hydrolysis yield was determined as described elsewhere48,49. CELLULOSOME CONSTRUCTS Two mini-scaffoldins

were designed in this study consisting of components from _C. thermocellum_ CipA scaffoldin. In particular, the X-module and type II dockerin dyad and the CBM were amplified from

pET28-XDock and pET28-CBM, respectively. Cohesin 7 was amplified from pAFM-c7A50. First, XDock was amplified with primers incorporating NdeI, NheI, KpnI, and SpeI sites at the 5′ end and two

STOP codons and a XhoI site at the 3′ end. The resulting fragment was cloned into a pET28 vector using NdeI and XhoI sites. Then the CBM was amplified and cloned into the previous vector

using NdeI and NheI sites. Next, cohesin 7 sequence was cloned using KpnI and SpeI sites to generate pET28-Scaf1. A second copy of cohesin 7 was then cloned into this vector in the SpeI site

to generate pETScaf2, containing two tandem cohesins. Both mini-scaffoldins carried a His6 tag at the N terminus. Integration of the LFCA_EG into the mini-cellulosome was accomplished by

cloning the LFCA_EG sequence into a pET28a vector between the NcoI and EcoRI sites. Then, the sequence of _C. thermocellum_ Cel8A dockerin (and N-terminal linker) was PCR amplified and

cloned at the C terminus of the LFCA_EG sequence between EcoRI and XhoI sites, thus generating pET28-LFCA_EG-Dockerin that carries a C-terminal hexa-histidine tag. LFCA_EG-CBM was generated

by replacing the Cel8A dockerin with a sequence containing the linker between Cel8A catalytic domain and dockerin, followed by the CipA CBM. Both mini-scaffoldins and LFCA_EG fusion proteins

were expressed in _E. coli_ BL21 star (DE3). Expression of mini-scaffoldins was carried out at 16 °C with 0.1 mM IPTG overnight, while LFCA_EG fusions and Cel8A were expressed at 37 °C for

3 h in 1 mM IPTG. Cultures were lysed by enzymatic digestion in 1 mg mL−1 lysozyme, 1% Triton X-100, 5 µg mL−1 DNAseI, and 5 µg mL−1 RNAse A and centrifuged to remove cell debris. Clarified

samples were incubated at 55 °C for 20 min, cooled in ice, and centrifuged to eliminate aggregated proteins. Affinity purification was then carried out using _HisTrap_ columns in an _ÅKTA

Purifier FPLC_ (GE Healthcare). Sample purity was evaluated by SDS–PAGE and proteins were concentrated in Tris 50 mM, NaCl 300 mM, and CaCl2 1 mM, pH 7, quantified by absorbance at 280 nm

with a NanoDrop (ThermoScientific) and stored in 50% glycerol. Mini-cellulosome assembly assays were performed by native PAGE. Different relations of proteins were incubated in 50 mM Tris,

300 mM NaCl, and 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7 at 37 °C for 1 h before running the gel. SdbA cohesin was also added to block XDock in the scaffoldin. The true enzyme–scaffoldin ratio was determined from

this analysis and according to that ratio, no free protein was found in excess. This ratio was used in the following experiments. Microcrystalline cellulose binding was assayed as described

previously32. Briefly, 10 µg of protein was incubated with 10 mg of Avicel (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4 °C for 1 h with gentle agitation. Samples were centrifuged and the supernatant was stored as

the unbound fraction. The pellet was washed three times and used as the bound fraction. Both samples were then analyzed by SDS–PAGE and BSA was used as a control. CELLULOSOME ACTIVITY ASSAYS

Proteins were incubated in acetate buffer, pH 5.5 containing 100 mM NaCl, 12 mM CaCl2, and 2 mM EDTA for 1 h at 37 °C to allow complex formation. Enzymes were used at 0.5 µM for Avicel and

PASC analyses, and at 0.35 µM for CMC assays. Scaffoldins were added at equimolar concentration according to native-PAGE analysis. BSA was added in all samples to minimize unspecific

enzyme–substrate interactions. Avicel assays were conducted for 24 h in an orbital shaker in 2-mL tubes containing a wing magnet to improve stirring, so that this insoluble substrate did not

precipitate. PASC was prepared as described elsewhere51. Assays with this substrate were conducted in similar tubes but in a heating block for 30 min. After incubation time, samples were

centrifuged and the soluble sugars present in solution in the supernatant were determined by the DNS assay. Absorbance was measured in a 96-well plate using a FLUOstar fluorimeter (BMG

Labtech, Germany) in the absorbance mode. CMC assays were conducted in a heating block using azo-CMC (Megazyme) as a substrate. The activity was determined according to the manufacturer’s

indications. CRYSTALLIZATION DATA COLLECTION AND STRUCTURE DETERMINATION Protein, at an initial concentration of 8.0 mg mL−1 in 50 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.8, was incubated with CMC at

double concentration for 30 min. The excess of ligand was removed by washing with the same buffer with centrifugation, using 0.5 ml concentration units (Amicon). The final protein

concentration was 17.0 mg mL−1, as determined spectrophotometrically. An initial crystallization screening was done using the vapor-diffusion technique in its hanging-drop configuration.

Crystallization experiments were set up in 24-well crystallization plates VDX (Hampton Research), using the 100-conditions kit from the Hampton Research Screen I&II. Hanging droplets

were prepared by mixing protein solution (1 µL) with reservoir solution (1 µL) on a 22 mm siliconized round coverslip inverted over a 500 µL reservoir. Crystals were obtained in conditions

C22 (0.2 M sodium acetate trihydrate, 0.1 M Tris hydrochloride, pH 8.5, and 30% w/v PEG 4 K) and C32 (0.1 M MES monohydrate, pH 6.5, 12% w/v PEG 20 K) of rod and hexagonal plate shapes,

respectively. For data collection, crystals were cryoprotected in the mother liquid containing 15% (v/v) glycerol, cryocooled in liquid nitrogen, and stored until data collection. Crystals

were tested at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (beam line ID30B). Data were indexed and integrated with XDS52, and scaled and reduced with AIMLESS53 of the CCP4 program suite54.

The structure was determined by molecular replacement, using the coordinates of the endoglucanase from _B. subtilis_ (PDB:3PZV) as the search model as suggested from Phyre255. The molecular

replacement solution was found using Phaser56 locating the six monomers in the asymmetric unit. Several cycles of manual building steps, Coot57, and structure refinement, phenix.refine58,

were done followed by continuous model check with MolProbity59, as implemented within the Phenix suite58. Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank

repository with accession code 6GJF. Figures were prepared with Pymol (Schrodinger, LLC, 2010). Details of data collection and processing, refinement statistics, and quality indicators of

the final model are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. COMPUTATIONAL STRUCTURAL CHARACTERIZATION We have run atomistic MD of Bs_EG, Tm_EG, and LFCA_EG, in the presence of a cellulosic

substrate starting from the experimental structures (PDB IDs: 3AMC, 3PTZ, and 6GJF, respectively). None of these structures were resolved in the presence of an oligosaccharide, and for this

reason, we had to introduce it manually using the following procedure. First, we fitted the structure of a tetrasaccharide formed by four units of d-glucose linked by β (1 → 4)-glycosidic

bonds on the corresponding atoms of the cellotetraose-bound Tm_EG E253A mutant (pdb 3PZT), so that the four glucose monomers corresponded to subsites −3, −2, −1, and +1, resulting in a

conformation that is compatible with catalysis. Having the tetrasaccharide well positioned, then we used the MultiSeq plugin60 available in the VMD software to fit each of the three enzyme

structures of interest on that of the Tm_EG mutant based on their structural alignment. The coordinates of sugar and enzyme were then combined, solvated, and energy minimized. Simulations

were run using an identical protocol for all three enzymes, involving a short NVT run with position restraints on the enzyme and the sugar, followed by removal of restrains on the enzyme, a

20 ps NPT run to equilibrate the box volume and a production run at 300 K in the NVT ensemble, using a stochastic dynamics integrator with 2 fs time steps. The particle mesh Ewald method61

was used for the electrostatics and the distances for all the hydrogen-heavy atom bonds were constrained using LINCS. All the simulations were run using the Gromacs 2018 software package62.

We used the optimized Amber03* force field63 for the protein with the TIP3P water model64. The doglycans tool65 was used to generate parameters for the oligosaccharide, so that they can be

read by the Gromacs software package. We chose the GLYCAM parameter set that is compatible with the Amber force field family66. Specifically, we used the prepreader.py script to prepare the

parameters for the carbohydrate chain. ELASTIC NETWORK MODELS To gain further insight on the slow conformational dynamics of the proteins of interest, we resort to ENMs. ENMs are based on

the assumption that the dynamic properties of proteins are dictated by the topology of native contacts67. This type of model, combined with normal mode analysis, has been very useful for a

variety of applications related to the study of protein dynamics, including the identification of functional conformational changes in enzymes and the comparison of ensembles of experimental

structures35,67. Here, we limit our study to the simplest and most broadly used type of ENM, the anisotropic network model (ANM). We have used the Python package ProDy68

(http://prody.csb.pitt.edu/) to generate ANMs of Tm_EG, Bs_EG, and LFCA_AG, using the same PDB files as for the MD simulations. The ANM is built using the Cα trace of the protein, whose

atoms are connected by harmonic springs, resulting in an energy function $$E_{{\mathrm{Network}}} = \frac{1}{2}\mathop {\sum }\limits_{ij} \gamma \left( {r_{ij} - r_{ij}^0} \right)^2$$ (1)

where the sum runs over pairs _ij_ of residues under a cutoff distance (_r_cut), the terms _r__ij_ and _r_ij0 correspond to the distances between pairs of Cα atoms in instantaneous and

reference configurations, respectively, and _γ__i_ are the force constants67. Here, we use the default parameters in ProDy for both cutoff distances (_r_c = 15 Å) and force constants (_γ_ =

1). The analysis of the Hessian of the potential returns the normal modes of the system. The lowest frequency normal modes are of greatest interest because they contain information about the

large-amplitude motions in the biomolecule. DATA AVAILABILITY Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Coordinates and

structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank repository with accession code 6GJF. REFERENCES * Bayer, E. A., Chanzy, H., Lamed, R. & Shoham, Y. Cellulose, cellulases

and cellulosomes. _Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol._ 8, 548–557 (1998). Article CAS Google Scholar * Farrell, A. E. et al. Ethanol can contribute to energy and environmental goals. _Science_

311, 506–508 (2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * Limayem, A. & Ricke, S. C. Lignocellulosic biomass for bioethanol production: current perspectives, potential issues and future

prospects. _Prog. Energy Combust. Sci._ 38, 449–467 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kumar, P., Barrett, D. M., Delwiche, M. J. & Stroeve, P. Methods for pretreatment of

lignocellulosic biomass for efficient hydrolysis and biofuel production. _Ind. Eng. Chem. Res._ 48, 3713–3729 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Anbar, M., Gul, O., Lamed, R., Sezerman,

U. O. & Bayer, E. A. Improved thermostability of _Clostridium thermocellum_ endoglucanase Cel8A by using consensus-guided mutagenesis. _Appl. Environ. Microbiol._ 78, 3458–3464 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Chang, C. J. et al. Exploring the mechanism responsible for cellulase thermostability by structure-guided recombination. _PLoS ONE_ 11, e0147485 (2016).

Article Google Scholar * Graham, J. E. et al. Identification and characterization of a multidomain hyperthermophilic cellulase from an archaeal enrichment. _Nat. Commun._ 2, 375 (2011).

Article Google Scholar * Maki, M., Leung, K. T. & Qin, W. The prospects of cellulase-producing bacteria for the bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass. _Int J. Biol. Sci._ 5, 500–516

(2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Molina-Espeja, P. et al. Beyond the outer limits of nature by directed evolution. _Biotechnol. Adv._ 34, 754–767 (2016). Article Google Scholar *

Gaucher, E. A., Govindarajan, S. & Ganesh, O. K. Palaeotemperature trend for Precambrian life inferred from resurrected proteins. _Nature_ 451, 704–707 (2008). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Perez-Jimenez, R. et al. Single-molecule paleoenzymology probes the chemistry of resurrected enzymes. _Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol._ 18, 592–596 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Manteca, A. et al. Mechanochemical evolution of the giant muscle protein titin as inferred from resurrected proteins. _Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol._ 24, 652–657 (2017). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Merkl, R. & Sterner, R. Ancestral protein reconstruction: techniques and applications. _Biol. Chem._ 397, 1–21 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Risso, V. A., Gavira, J.

A., Mejia-Carmona, D. F., Gaucher, E. A. & Sanchez-Ruiz, J. M. Hyperstability and substrate promiscuity in laboratory resurrections of Precambrian beta-lactamases. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._

135, 2899–2902 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Alcalde, M. When directed evolution met ancestral enzyme resurrection. _Microb. Biotechnol._ 10, 22–24 (2017). Article Google Scholar

* Bayer, E. A., Shimon, L. J., Shoham, Y. & Lamed, R. Cellulosomes-structure and ultrastructure. _J. Struct. Biol._ 124, 221–234 (1998). Article CAS Google Scholar * Nordon, R. E.,

Craig, S. J. & Foong, F. C. Molecular engineering of the cellulosome complex for affinity and bioenergy applications. _Biotechnol. Lett._ 31, 465–476 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar

* Drummond, A. J., Suchard, M. A., Xie, D. & Rambaut, A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. _Mol. Biol. Evol._ 29, 1969–1973 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Hedges, S. B., Marin, J., Suleski, M., Paymer, M. & Kumar, S. Tree of life reveals clock-like speciation and diversification. _Mol. Biol. Evol._ 32, 835–845 (2015). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Nobles, D. R., Romanovicz, D. K. & Brown, R. M. Cellulose in cyanobacteria. origin of vascular plant cellulose synthase? _Plant Physiol._ 127, 529–542 (2001). Article CAS

Google Scholar * GL, M. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. _Anal. Chem._ 31, 426–428 (1959). Article Google Scholar * Galbe, M. & Zacchi, G.

Pretreatment: the key to efficient utilization of lignocellulosic materials. _Biomass Bioenergy_ 46, 70–78 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Robert, F. & Chaussidon, M. A

palaeotemperature curve for the Precambrian oceans based on silicon isotopes in cherts. _Nature_ 443, 969–972 (2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * Risso, V. A., Gavira, J. A. &

Sanchez-Ruiz, J. M. Thermostable and promiscuous Precambrian proteins. _Environ. Microbiol._ 16, 1485–1489 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Garcia, A. K., Schopf, J. W., Yokobori, S.

I., Akanuma, S. & Yamagishi, A. Reconstructed ancestral enzymes suggest long-term cooling of Earth’s photic zone since the Archean. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 114, 4619–4624 (2017).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Wu, B. et al. Processivity and enzymatic mechanism of a multifunctional family 5 endoglucanase from _Bacillus subtilis_ BS-5 with potential applications in

the saccharification of cellulosic substrates. _Biotechnol. Biofuels_ 11, 20 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Zheng, F. & Ding, S. Processivity and enzymatic mode of a glycoside

hydrolase family 5 endoglucanase from Volvariella volvacea. _Appl. Environ. Microbiol._ 79, 989–996 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ling, Z., Chen, S., Zhang, X., Takabe, K. &

Xu, F. Unraveling variations of crystalline cellulose induced by ionic liquid and their effects on enzymatic hydrolysis. _Sci. Rep._ 7, 10230 (2017). Article Google Scholar * David Pot, G.

C. et al. Genetic control of pulp and timber properties in maritime pine (_Pinus pinaster_ Ait.). _Ann. For. Sci._ 59, 563–575 (2002). Article Google Scholar * Kinnarinen, T. &

Hakkinen, A. Influence of enzyme loading on enzymatic hydrolysis of cardboard waste and size distribution of the resulting fiber residue. _Bioresour. Technol._ 159, 136–142 (2014). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Vicente, A. I. et al. Evolved alkaline fungal laccase secreted by _Saccharomyces cerevisiae_ as useful tool for the synthesis of C–N heteropolymeric dye. _J. Mol.

Catal. B_ 134, 323–330 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Vazana, Y., Morais, S., Barak, Y., Lamed, R. & Bayer, E. A. Designer cellulosomes for enhanced hydrolysis of cellulosic

substrates. _Methods Enzym._ 510, 429–452 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zverlov, V. V., Kellermann, J. & Schwarz, W. H. Functional subgenomics of _Clostridium thermocellum_

cellulosomal genes: identification of the major catalytic components in the extracellular complex and detection of three new enzymes. _Proteomics_ 5, 3646–3653 (2005). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Chen, C., Tian, W., Lei, X., Liang, J. & Zhao, J. CASTp 3.0: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 46, W363–W367 (2018). Article Google

Scholar * Bakan, A. & Bahar, I. The intrinsic dynamics of enzymes plays a dominant role in determining the structural changes induced upon inhibitor binding. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_

106, 14349–14354 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Romero-Romero, M. L. et al. Selection for protein kinetic stability connects denaturation temperatures to organismal temperatures

and provides clues to Archaean life. _PLoS ONE_ 11, e0156657 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Zou, T., Risso, V. A., Gavira, J. A., Sanchez-Ruiz, J. M. & Ozkan, S. B. Evolution of

conformational dynamics determines the conversion of a promiscuous generalist into a specialist enzyme. _Mol. Biol. Evol._ 32, 132–143 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kratzer, J. T.

et al. Evolutionary history and metabolic insights of ancient mammalian uricases. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 111, 3763–3768 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zakas, P. M. et al.

Enhancing the pharmaceutical properties of protein drugs by ancestral sequence reconstruction. _Nat. Biotechnol._ 35, 35–37 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Shahab, R. L.,

Luterbacher, J. S., Brethauer, S. & Studer, M. H. Consolidated bioprocessing of lignocellulosic biomass to lactic acid by a synthetic fungal-bacterial consortium. _Biotechnol. Bioeng._

115, 1207 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gomez-Fernandez, B. J. et al. Directed -in vitro- evolution of Precambrian and extant Rubiscos. _Sci. Rep._ 8, 5532 (2018). Article Google

Scholar * Pucci, F., Bourgeas, R. & Rooman, M. Predicting protein thermal stability changes upon point mutations using statistical potentials: introducing HoTMuSiC. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 23257

(2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 32, 1792–1797 (2004). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Abascal, F., Zardoya, R. & Posada, D. ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. _Bioinformatics_ 21, 2104–2105 (2005). Article CAS Google Scholar

* Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. _Mol. Biol. Evol._ 24, 1586–1591 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Nozaki, Y. Determination of the concentration of

protein by dry weight a comparison with spectrophotometric methods. _Arch. Biochem. Biophys._ 249, 437–446 (1986). Article CAS Google Scholar * Teugjas, H. & Valjamae, P. Selecting

beta-glucosidases to support cellulases in cellulose saccharification. _Biotechnol. Biofuels_ 6, 105 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * van Wyk, J. P. H., Sibiya, J. B. M. &

Dhlamini, R. B. Saccharification and change of incubation pH during the bioconversion of various waste paper materials with cellulase from _Aspergillus niger_. _Int. J. Pure Appl. Biosci._

3, 12–20 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Van Dyk, J. S. P. B.I A review of lignocellulose bioconversion using enzymatic hydrolysis and synergistic cooperation between enzymes—factors

affecting enzymes, conversion and synergy. _Biotechnol. Adv._ 30, 1458–1480 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Valbuena, A. et al. On the remarkable mechanostability of scaffoldins and the

mechanical clamp motif. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 106, 13791–13796 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lamed, R., Kenig, R., Setter, E. & Bayer, E. A. Major characteristics of the

cellulolytic system of _Clostridium thermocellum_ coincide with those of the purified cellulosome. _Enzym. Microb. Technol._ 7, 37–41 (1985). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kabsch, W. Xds.

_Acta Crystallogr. D_ 66, 125–132 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Evans, P. R. & Murshudov, G. N. How good are my data and what is the resolution? _Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D_ 69,

1204–1214 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Collaborative, Computational Project, The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. _Acta Crystallogr D_ 50, 760–763 (1994).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15299374 * Kelley, L. A., Mezulis, S., Yates, C. M., Wass, M. N. & Sternberg, M. J. E. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and

analysis. _Nat. Protoc._ 10, 845–858 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bunkoczi, G. et al. Phaser.MRage: automated molecular replacement. _Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D_ 69, 2276–2286

(2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. _Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D_ 66, 486–501 (2010). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. _Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D_ 66, 213–221 (2010). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. _Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D_ 66, 12–21 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar

* Roberts, E., Eargle, J., Wright, D. & Luthey-Schulten, Z. MultiSeq: unifying sequence and structure data for evolutionary analysis. _BMC Bioinforma._ 7, 382 (2006). Article Google

Scholar * Darden, T., York, D. & Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. _J. Chem. Phys._ 98, 10089–10092 (1993). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. _SoftwareX_ 1-2, 19–25 (2015). Article

Google Scholar * Best, R. B. & Hummer, G. Optimized molecular dynamics force fields applied to the helix−coil transition of polypeptides. _J. Phys. Chem. B_ 113, 9004–9015 (2009).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J. D., Impey, R. W. & Klein, M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. _J.

Chem. Phys._ 79, 926–935 (1983). Article CAS Google Scholar * Danne, R. et al. doGlycans—tools for preparing carbohydrate structures for atomistic simulations of glycoproteins,

glycolipids, and carbohydrate polymers for GROMACS. _J. Chem. Inf. Model._ 57, 2401–2406 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kirschner, K. N. et al. GLYCAM06: a generalizable

biomolecular force field. Carbohydrates. _J. Comput. Chem._ 29, 622–655 (2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bahar, I., Lezon, T. R., Yang, L.-W. & Eyal, E. Global dynamics of

proteins: bridging between structure and function. _Annu. Rev. Biophys._ 39, 23–42 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bakan, A., Bahar, I. & Meireles, L. M. ProDy: protein dynamics

inferred from theory and experiments. _Bioinformatics_ 27, 1575–1577 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Prof. Ed Bayer’s group for kindly

providing the plasmids used in the mini-cellulosome constructs. Research was supported by the Basque Government grant ELKARTEK to R.P.-J, and also partly by Ministry of Economy and

Competitiveness (MINECO) grant BIO2016-77390-R, BFU2015-71964 to R.P.-J., BIO2016-74875-P to J.A.G., and CTQ2015-65320-R and RYC-2016-19590 to D.D.S.; European Commission grant CIG Marie

Curie Reintegration program FP7-PEOPLE-2014 to R.P.-J, and European Commission grant NMP-FP7 604530-2 (_CellulosomePlus_), and the ERA-IB EIB.12.022 grant (_FiberFuel_) funded by the MINECO

(PCIN-2013-011-C02-01) to M.C.-V. We also thank Fundación Repsol and Gipuzkoako Foru Aldundia for financial support. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally:

Borja Alonso-Lerma, Albert Galera-Prat, Nadeem Joudeh. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * CIC nanoGUNE, San Sebastian, 20018, Spain Nerea Barruetabeña, Borja Alonso-Lerma, Leire Barandiaran, Leire

Aldazabal, Maria Arbulu & Raul Perez-Jimenez * Cajal Institute, CSIC, Madrid, 28002, Spain Albert Galera-Prat & Nadeem Joudeh * Prospero Biosciences, S.L., San Sebastian, 20018,

Spain Maria Arbulu & Mariano Carrion-Vazquez * Department of Biocatalysis, Institute of Catalysis, CSIC, Madrid, 28049, Spain Miguel Alcalde * Faculty of Chemistry, University of the

Basque Country, San Sebastian, 20018, Spain David De Sancho * Donostia International Physics Center (DIPC), San Sebastian, 20018, Spain David De Sancho * Ikerbasque Foundation for Science,

Bilbao, 48013, Spain David De Sancho & Raul Perez-Jimenez * Laboratory of Crystallographic Studies, IACT (CSIC-UGR), Granada, 18100, Spain Jose A. Gavira * Evolgene Genomics, S.L., San

Sebastian, 20018, Spain Raul Perez-Jimenez Authors * Nerea Barruetabeña View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Borja Alonso-Lerma View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Albert Galera-Prat View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Nadeem

Joudeh View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Leire Barandiaran View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Leire Aldazabal View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Maria Arbulu View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Miguel Alcalde View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * David De Sancho View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jose A. Gavira View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mariano Carrion-Vazquez View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Raul Perez-Jimenez View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CONTRIBUTIONS R.P.-J. conceived the project. R.P.-J., D.D.S., A.G.-P., and M.C.-V. designed research. N.B. and R.P.-J. performed phylogenetic analysis. N.B., B.A.-L., A.G.-P., N.J., L.B.,

L.A., Ma.A., and Mi.A. carried out protein expression, purification, sample preparation, quantification, and activity assays. N.B., A.G.-P., D.D.S., M.C.-V., and R.P.-J. performed data

analysis. D.D.S. prepared and ran the computational calculations. J.A.G. crystallized, analyzed, and solved the structure. All authors contributed to writing, revising, completing, and

editing the paper. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Raul Perez-Jimenez. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

PUBLISHER’S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation,

distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and

indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to

the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

CITE THIS ARTICLE Barruetabeña, N., Alonso-Lerma, B., Galera-Prat, A. _et al._ Resurrection of efficient Precambrian endoglucanases for lignocellulosic biomass hydrolysis. _Commun Chem_ 2,

76 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0176-6 Download citation * Received: 29 January 2019 * Accepted: 30 May 2019 * Published: 01 July 2019 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-019-0176-6 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative