- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation catalyzed by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) is one of the immediate cellular responses to DNA damage. The histone PARylation factor 1 (HPF1) discovered

recently to form a joint active site with PARP1 and PARP2 was shown to limit the PARylation activity of PARPs and stimulate their NAD+-hydrolase activity. Here we demonstrate that HPF1 can

stimulate the DNA-dependent and DNA-independent autoPARylation of PARP1 and PARP2 as well as the heteroPARylation of histones in the complex with nucleosome. The stimulatory action is

detected in a defined range of HPF1 and NAD+ concentrations at which no HPF1-dependent enhancement in the hydrolytic NAD+ consumption occurs. PARP2, comparing with PARP1, is more efficiently

stimulated by HPF1 in the autoPARylation reaction and is more active in the heteroPARylation of histones than in the automodification, suggesting a specific role of PARP2 in the

ADP-ribosylation-dependent modulation of chromatin structure. Possible role of the dual function of HPF1 in the maintaining PARP activity is discussed. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS

HPF1-DEPENDENT HISTONE ADP-RIBOSYLATION TRIGGERS CHROMATIN RELAXATION TO PROMOTE THE RECRUITMENT OF REPAIR FACTORS AT SITES OF DNA DAMAGE Article 27 April 2023 HPF1 REMODELS THE ACTIVE SITE

OF PARP1 TO ENABLE THE SERINE ADP-RIBOSYLATION OF HISTONES Article Open access 15 February 2021 BRIDGING OF DNA BREAKS ACTIVATES PARP2–HPF1 TO MODIFY CHROMATIN Article 16 September 2020

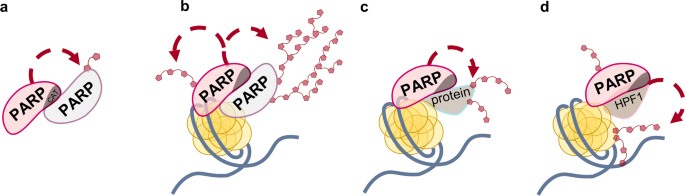

INTRODUCTION Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation) is a dynamic post-translational modification of biomolecules that plays an indispensable role in regulating a number of biological processes,

including DNA damage response. Poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) composed of linear and/or branched repeats of ADP-ribose is synthesized by enzymes called poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) that

utilize NAD+ as a substrate to modify themselves (automodification) (Fig. 1a, b) or target molecules (heteromodification)1,2 (Fig. 1c, d). The best studied PARP family member, PARP1, is the

abundant nuclear protein involved in multiple cellular processes, among them, DNA repair regulation. PARP1 serves as a sensor of the DNA lesions usually induced by ionizing irradiation and

oxidative stress and signals to recruit the appropriate proteins to the sites of damage3,4. PARP2 was also discovered as an enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of PAR5. The role of PARP2 and

its cooperation with PARP1 is under intensive investigation6,7,8,9,10. In human cells, the majority of PARP activity is exerted by PARP1 (around 90%) and by PARP2 (10‒15%)7. It is known

that neither PARP1 nor PARP2 is required for viability in mice, but parp1−/−parp2−/− double knockouts are embryonic lethal with considerable genomic instability11. PARP2 shares significant

homology with PARP1 in the catalytic domain structure, but differs in the domain architecture due to the absence of zinc fingers and BRCT domain7. Roles of PARP1 and PARP2 in base excision

repair and single-strand break repair were intensively studied12,13,14. Overlapping functions of PARP1 and PARP2 in regulation of these processes were shown by using model DNA duplexes15,16

as well as nucleosomes17,18. PARP2 is comparable with or even more efficient than PARP1 in binding DNA breaks, but has a lower affinity for intact DNA and AP sites8,16,19. Difference in the

affinities of PARP1 and PARP2 for various DNA structures in the nucleosome context was lately revealed18. PARP2 synthesizes shorter PAR chains than PARP1 does and also inhibits

PARP1-catalyzed PAR synthesis via hetero-oligomerization of the two PARPs8,10. It has been shown that removal of histone H3 is largely suppressed in PARP2-deficient cells20. Thus, PARP1 and

PARP2 can perform both overlapping and specific functions in maintaining genome stability, and these enzymes cooperate in the regulation of cellular processes. Recently the new histone

PARylation factor (HPF1) modulating activity of PARP1 and PARP2 was discovered21,22. HPF1 was shown to complete the active site of these enzymes via complex formation, and the role of the

joint active site was suggested to switch the PARylation specificity to serine residues23. HPF1 plays an essential role in the PARP1- and PARP2-catalyzed PARylation of histones22,24,25. It

was proposed that HPF1 binds only the DNA-activated form of PARP1/PARP2 because the autoinhibitory helical domain (HD) when bound to the ADP-ribosyl transferase (ART) subdomain of the

catalytic (CAT) domain prevents complex formation of HPF1 with PARP1/PARP222,26,27,28,29. The conformational change of HD induced by DNA/nucleosome binding promotes the interaction of

PARP1/PARP2 with HPF127,30. It is interesting that shortening of the synthesized PAR chains was detected in the presence of HPF122. The authors explained this effect by shielding of amino

acid residues important for PAR chain elongation (His826 and His381 in PARP1 and PARP2, respectively) in the complex with HPF1. In addition to affecting the substrate specificity and the

length of polymer chain in the ADP-ribosylation reaction, HPF1 was shown to enhance NAD+-hydrolysis catalyzed by PARP131. Recently it was shown that initiation and elongation steps of

ADP-ribosylation are distinctly regulated by HPF1, ARH3, and PARG hydrolases, and that the HPF1-dependent initial attachment of ADP-ribose to Ser residue can be elongated by PARP1 alone32.

PARP1 and PARP2 are known as therapeutic targets for the treatment of malignant tumors and other diseases. Several inhibitors of PARP are already using as anticancer drugs. Cells with

knockout of HPF1 revealed high sensitivity to PARP inhibitors21. Rudolph and coauthors from Luger’s group showed that HPF1 differently modulates affinity of some PARP inhibitors for the

PARP1-nucleosome complex, but this effect does not extend to PARP233. Therefore, the comparative study of the mechanism of HPF1-dependent modulation of the activities of PARP1 and PARP2 is

of particular interest. In the present study, we compared effects produced by HPF1 on the PARP1 and PARP2 activities in the autoPARylation reaction performed in the presence of DNA or

nucleosome, as well as in the heteroPARylation of histones. HPF1 was found to stimulate the automodification of both PARP1 and PARP2 in a concentration-dependent manner, with the effects

detected for PARP2 exceeding those for PARP1. Under optimal HPF1 concentration (produced the highest stimulatory action) no enhancement of NAD+-hydrolase activity of PARPs was detected.

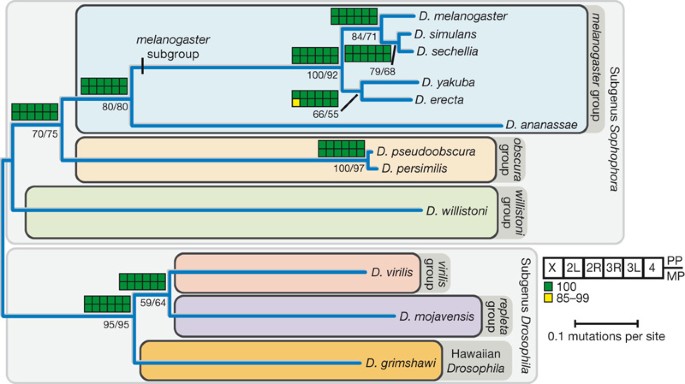

PARP2 was revealed to catalyze more efficiently modification of histones than the automodification. RESULTS HPF1 ENHANCES PARP1 AND PARP2 AUTOMODIFICATION CONCOMITANTLY WITH THE SWITCH OF

ADP-RIBOSYLATION ONTO HISTONES Influence of HPF1 on the activities of PARP1 and PARP2 in the automodification reaction and heteromodification of histones was tested at varied concentrations

of HPF1. To activate PARP1 and PARP2, a model 147-mer double-stranded DNA and the nucleosome core particle (NCP) constructed from this DNA were used. The products of PARylation reaction were

analyzed by SDS-PAGE separation and quantification, using [32P]NAD+ (Fig. 2a, b). The presence of HPF1 even at a limited concentration (60 nM in sample 2 compared to 500 nM of PARP1/2) was

detected to stimulate PARylation of histones. The increasing concentrations of HPF1 affected the total ADP-ribosylation level of PARPs and histones as well as the length of ADP-ribose

polymer attached to the proteins. The heterogeneous mixtures of modified proteins with quite different electrophoretic mobilities (visualized as smearing) became more uniform in the presence

of HPF1 as shown by the tight intense band with the increased electrophoretic mobility corresponding to the oligo/mono(ADP-ribosyl)ated proteins. The stimulatory effects produced by HPF1 on

the automodification of PARP1/PARP2 were more pronounced when nucleosome instead of DNA was used for the PARP activation. The maximal effects produced by HPF1 on the PARP1-catalyzed

automodification in the presence of nucleosome (a 6-fold increase) and DNA (a 3-fold increase) were observed at a 2-fold excess of HPF1 over PARP1 (Fig. 2c). The level of PARP2

automodification was enhanced to the maximal extent (8‐ and 5‐fold in the presence of NCP and DNA, respectively) by the equimolar HPF1 concentration (Fig. 2d). When HPF1 concentration was

further increased, its stimulatory effect on the automodification of both PARP1 and PARP2 decreased. The concentration dependences of effects produced by HPF1 on PARylation of histones

catalyzed by PARP1 and PARP2 were similar (Fig. 2c, d). At the same time, there was a significant difference between PARP1 and PARP2 in the relative levels of auto- and heteroPARylation

determined as % of total ADP-ribose covalently bound to PARP and histones (Fig. 2e, f). While the preferred target of PARP1-catalyzed modification at various concentrations of HPF1 was PARP1

itself (Fig. 2e), most of the PAR synthesized by PARP2 was attached to histones (Fig. 2f). Additionally, the ratio of modification levels of histones and PARP1 decreased with increasing

concentration of HPF1, while the respective value in the case of PARP2 was stable when reached ~75%. To confirm the tendency of PAR chain synthesized by PARP1/PARP2 to be shortened in the

presence of HPF1 as shown previously31 and here (Fig. 2a, b), we analyzed the length of PAR synthesized in the absence or presence of three different concentrations of HPF1. Results of

autoradiographic analysis of bulk PAR (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Note 1) show that size distribution of PAR synthesized by both PARP1 and PARP2 was affected by HPF1 in a

concentration-dependent manner: increasing the HPF1 concentration enlarged the relative amount of small PAR fraction (1‒10-mers). The concentration dependence of the effect was more

pronounced in the case of PARP2, especially when NCP was used to activate the PARylation reaction: the presence of HPF1 at the highest concentration enhanced switch of PARP2 activity to

mono(ADP-ribosyl)ation reaction. HPF1 PROMOTES PARP1/PARP2-CATALYZED PARYLATION IN THE ABSENCE OF DNA AND AT THE EXCESSIVE DNA CONCENTRATION A transient (low affinity) direct interaction of

PARP1 with HPF1 proposed previously22, prompted us to hypothesize possible stimulation of PARP1- and PARP2-catalyzed autoPARylation by HPF1 in the absence of any activator (NCP or DNA). To

verify this hypothesis, the DNA-independent activity (i.e., in the absence of NCP or DNA) of PARP1 and PARP2 was tested in the presence of increasing concentrations of HPF1. Preliminary

experiments performed with and without DNAse treatment revealed PARP1, PARP2, and HPF1 preparations being free of DNA contamination (Supplementary Fig. 2; Supplementary Note 2). Low levels

of the basal activity detected for both enzymes in the absence of DNA were nevertheless revealed to be increased to different extents in the presence of HPF1 (Fig. 3a, b). The maximal effect

on the autoPARylation level of PARP2 was slightly higher (2.4-fold increase) as compared to that of PARP1 (1.6-fold increase). Interestingly, the maximal effect detected for PARP2 was

produced by a 4‐fold excess of HPF1, while in the presence of DNA or nucleosome, the maximal stimulation was observed at an equimolar ratio of HPF1 and PARP2. The dependence of the optimal

HPF1 concentration on the existence of PARP1/2 in the DNA-bound or DNA-free state may result from a higher stability of the ternary complex22. Taking into account the capability of HPF1 to

stimulate the activities of PARP1 and PARP2 in both the absence and presence of activating DNA, we explored further the PARP1/PARP2-catalyzed automodification reaction in the presence of a

high DNA concentration insuring near-complete binding of PARP to DNA, in contrast to conditions used in the experiments described above (see Fig. 2). The maximal stimulatory effects produced

by HPF1 on the automodification reaction were observed at a 4‐fold excess of HPF1 over PARP1/PARP2 (Fig. 3c). The extent of stimulation detected for PARP2 might be slightly higher as

compared to that for PARP1 (3‐fold vs. 2.4‐fold). Combined, the data obtained in the absence and presence of various DNA concentrations indicate that the HPF1-produced stimulation depends on

the relative amounts of PARP in the DNA-free and DNA-bound states. The previously reported data on modulation of PARP1/PARP2 activity by HPF122,24,34 were obtained at high NAD+

concentrations (0.5‒5 mM vs. 1 μM in our experiments). It was therefore important to explore dependence of the HPF1-produced effects on the NAD+ concentration. Preliminary experiments

performed for PARP1 (at a fixed PARP1 and HPF1 concentration) in a wide range of NAD+ concentrations revealed that the automodification level was enhanced at low (0.5‒3 μM) and suppressed at

high (35‒300 μM) NAD+ concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 4). A detailed study of the effects produced by various HPF1 concentrations on the PARP1/PARP2 automodification level in the

presence of 10 μM NAD+ showed maximal stimulating effects at a 2-fold excess of HPF1 over PARP1/PARP2 (Fig. 3d). Notably, the extent of stimulation detected in these conditions for PARP1 was

slightly higher than for PARP2 (2.3‐fold vs. 1.4‐fold). Thus, our data show that HPF1 can stimulate the PARP1/PARP2-catalyzed automodification over the limited range of NAD+ concentrations.

HPF1 MODULATES THE AUTO- AND HETEROMODIFICATION ACTIVITIES OF PARP1 AND PARP2 AT THE INITIAL STAGE OF THE REACTIONS Difference between PARP1 and PARP2 in the stimulatory effects produced by

HPF1 on their activities in reactions performed over a fixed incubation time, in the varied reaction conditions prompted us to explore kinetics of the auto- and heteromodification reactions

catalyzed by the PARPs. Kinetic measurements of the DNA-dependent activities (in the presence of NCP) in the absence or presence of HPF1 (at the optimal concentration) were performed at 1

μM and 10 μM NAD+ concentrations (Fig. 4a, b). The initial rate of automodification determined to be significantly higher for PARP1 than for PARP2 (13‐fold and 70‐fold at 1 μM and 10 μM NAD+

concentration, respectively) was enhanced by HPF1 more substantially at low than at higher NAD+ concentration (9‐fold vs. 2‐fold) (Table 1). The respective value for PARP2 was enhanced

significantly at both NAD+ concentrations (11‐ and 18‐fold). As a result, the difference between PARP1 and PARP2 in the initial rates of automodification in the presence of HPF1 was one

order of magnitude at the low and higher NAD+ concentration. The initial rate of PARP2-catalyzed histone modification exceeds (1.6‐fold) or is comparable with the automodification rate. On

the contrary, the PARP1-catalyzed heteromodification reaction is slower than the automodification (~1.8-fold difference in the rates). Kinetic measurements of the DNA-independent activities

of PARP1 and PARP2 were performed in the absence or presence of HPF1 at 1 μM NAD+ concentration (Fig. 4c). Differences between PARP1 and PARP2 in the initial rates of DNA-independent

automodification, in the absence and presence of HPF1, were within the experimental error (Table 1). This similarity between PARPs 1 and 2 provides evidence that their basal activities are

immediately related to the conserved catalytic domain and can be enhanced to some extent by the direct interaction with HPF1. Comparison of the initial rates of DNA-independent and

DNA-dependent modification shows that the DNA-induced activation is more significant for PARP1 (43-fold increase in the absence and 150-fold in the presence of HPF1) than for PARP2 (5- and

11-fold increase in the absence and presence of HPF1, respectively). Notably, the initial rate of automodification in the absence of HPF1 depends on NAD+ concentration more strongly for

PARP1- than PARP2-catalyzed reaction (27-fold increase at 10 μM vs. 1 μM NAD+ concentration for PARP1 and 5‐fold for PARP2). This difference, which can be explained by a higher activity of

PARP1 at the elongation step10,16, disappeared in the presence of HPF1 (6- and 8-fold increase at 10 μM vs. 1 μM NAD+ concentration for PARP1 and PARP2, respectively). These data suggest

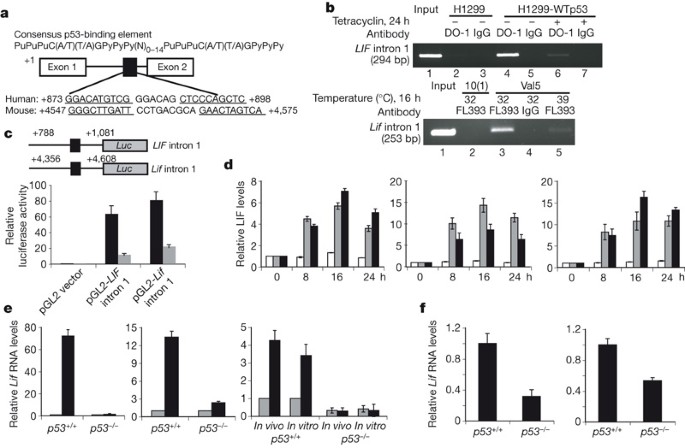

that HPF1 controls the balance between initiation and elongation events upon the ADP-ribosylation reaction. THE EXTENT OF HPF1-PROMOTED SWITCH OF THE SUBSTRATE SPECIFICITY DEPENDS ON THE

RELATIVE PARP AND HPF1 CONCENTRATIONS To examine how the HPF1-induced stimulation of PARPs activities is related to switching the amino acid specificity of ADP-ribosylation, we explored

resistance of the modification to hydroxylamine (HA), which removes specifically ADP-ribose (ADPR) from Asp/Glu residues25. The autoradiographic analysis shows that the most portion of ADPR

incorporated into PARP1/PARP2 in the absence of HPF1 was removed by HA, while the loss of modification in the presence of the optimal HPF1 concentration did not exceed 12‒20% (Fig. 5a, b).

Complete resistance to HA was detected for modification in the presence of a large excess of HPF1. These data indicate that: (1) the extent of switch of the amino acid specificity depends on

the relative amount of PARP in the HPF1-bound state; (2) the maximal stimulating effect of HPF1 results from the incomplete switch. NAD+-HYDROLASE ACTIVITY OF PARPS 1 AND 2 IS ENHANCED BY

THE LARGE HPF1 EXCESS The NAD+-hydrolase activity, detected for PARP1 in the early study35, was recently shown to be significantly stimulated in the presence of HPF131. The HPF1-induced

switching of PARP1 activity from PAR synthesis to NAD+ hydrolysis with formation of free ADP-ribose (up to 90% consumption termed “treadmilling”) was observed in the presence of 20-fold

excess of HPF1 over PARP131. We were interested to compare the NAD+-hydrolase activities at different HPF1 concentrations: optimal for stimulation of ADP-ribosylation reaction and in the

large excess (see Fig. 2c, d). The reactions catalyzed by PARP1 and PARP2 activated by NCP were performed without HPF1 and in its presence at the two different concentrations, and the

relative amounts of 32P-labelled ADP-ribose incorporated into PARPs and histones and released in free form due to NAD+ hydrolysis were determined (Fig. 6a-d). In the presence of the optimal

HPF1 concentration, the relative amount of free ADP-ribose was lower than in the absence (~5‐fold for PARP1 and ~2‐fold for PARP2) or at the large excess (~6‐fold for PARP1 and ~4‐fold for

PARP2). Thus, the NAD+-hydrolase activity of both PARP1 and PARP2 is enhanced by the large excess of HPF1. DISCUSSION PARP1 is a key nuclear enzyme that catalyzes PAR synthesis as DNA damage

response and regulates DNA repair and other processes in cell. It was supposed that PARP1 itself is the most common target of PARylation36. At the same time other proteins have been

identified as efficient targets of PARylation37,38,39. It is known that PARP1 cooperates with specific partner proteins in numerous cellular processes40. Some of these proteins stimulate

PARP1 activity and modulate the length of PAR chain37,41,42. HPF1 (also known as C4orf27) was discovered recently in the Ahel’s group as a cofactor of PARP1, responsible for regulation of

ADP-ribosylation signaling in the DNA damage response21. Using _C4orf27_−/− cells it was shown that loss of HPF1 induced hyper-autoPARylation of PARP1 and abrogated histone ADP-ribosylation.

The capability of HPF1 to limit the level of PARP1 automodification via shortening of PAR chain can be explained by the interaction of HPF1 with His residue (His826 and His381 in PARP1 and

PARP2, respectively)22, which is critical for PAR chain elongation43. On the other hand, the Luger’s group showed that HPF1 promotes the NAD+-hydrolase activity of PARP1, which can lead to

depletion of NAD+ and thereby prevent production of the long PAR molecules31. The authors suggest that the lack of readily available substrate for PARylation due to HPF1-blockage of the PAR

chain elongation site results in the increased hydrolase activity. Previous data demonstrating HPF1-induced modulation of PARP activity were obtained at the large excess of HPF1 relative to

PARP1/221,31. At the same time the PARP1 concentration in HeLa cells is significantly higher than the HPF1 concentration (∼2030 vs ∼104 nМ)21. Therefore, it was reasonable to explore the

influence of varied concentration of HPF1 on the activity of PARP1 and PARP2 in the autoPARylation and histone modification. First, we have found that PARylation in the presence of

increasing HPF1 concentration results in shortening of the chain length of PAR covalently bound to PARPs and histones. Interestingly, this effect was observed at both low and high NAD+

concentration (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Fig. 1). Further, we found that the inhibitory action of HPF1 on the PARP1 automodification demonstrated previously31 depends on the experimental

conditions. At a low NAD+ concentration we used in most experiments, the 32-fold excess of HPF1 over PARP1/PARP2 abolished the stimulatory effect detected at the optimal concentration (Fig.

2c, d). On the other hand, at the high NAD+ concentration (35‒300 μM) the automodification activity of PARP1 was substantially suppressed even by the 2-fold excess of HPF1 (Supplementary

Fig. 4). The affinity of HPF1 for PARP1/2 is very low: the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) determined for the PARP2-HPF1 complex is in the micromolar range (>3 μM)34, and a less

stable PARP1-HPF1 complex was undetectable24. The interaction of HPF1 with PARPs is stabilized in the ternary complex with nucleosome: the Kd values of 790 nM and 280 nM were determined for

the HPF1-PARP1-Nuc165 and HPF1‒PARP2‒Nuc165 complexes33,34. These high Kd values justify high concentrations of HPF1 and its large excess over the PARPs concentration in previous

publications21,31. Here we revealed that: (1) HPF1 stimulates PARylation of histones even at limited (~8-fold lower) concentration relative to that of PARPs 1 and 2; (2) the maximal

stimulating effect on the autoPARylation of PARPs in the presence of both DNA and nucleosome was observed at the equimolar (2-fold excessive) concentration of HPF1 relative to the PARP2

(PARP1) concentration (0.5 μM) (Fig. 2c, d). The lower value of optimal HPF1 concentration determined for PARP2 correlates with the higher stability of the respective ternary complex (as

described above). We assume that interaction of HPF1 with PARPs is more efficient in the catalytically active complex due to opening of the HD domain promoted by the NAD+ binding in the

active center of PARPs30. Probably, accommodation of NAD+ in its binding pocket dynamically alters structure of the PARP-nucleosome complex and facilitates HPF1 binding. The HPF1-induced

stimulating effect on the PARPs activities was higher in the presence of nucleosome than model DNA, while the concentrations of HPF1 optimal for the stimulatory action were nearly the same,

independently of the type of DNA activator. Possibly, the nucleosome-induced rearrangement of CAT is more suitable for the accommodation of HPF1 and NAD+ substrate30. The PARP1 active site

interacts with HPF1 in the binary complex of HPF1 with CAT deprived of HD (co-crystallized in the absence of NAD+)24,43, indicating the necessity of CAT rearrangement for mutual

accommodation of HPF1 and NAD+. Taken together, these data suggest the key role of the degree of HD unfolding for the formation of the combined HPF1-PARP active site. In addition, our data

show that the regularities of HPF1 influence on the PARPs activity are generally manifested on both NCP and DNA. We showed that the extent of HPF1-dependent switch of PARylation specificity

is determined by the relative amount of PARP1/2 in the HPF1-bound state. In the conditions of HPF1-dependent stimulation, 12–20% of ADP-ribosylation is unstable under treatment with HA (Fig.

5b), indicating modification of Asp/Glu residues by HPF1-free PARP molecules. To switch completely the reaction specificity, a large excess of HPF1 over PARP is required. The next finding

of the present study is the more considerable HPF1-induced modulation of PARP2 activity in comparison with PARP1. The maximal level and the initial rate of PARP2 automodification in the

presence of NCP/DNA were enhanced more intensively as compared to those for PARP1 (Fig. 2c, d; Fig. 4a, b; Table 1), and the optimal HPF1 concentration for the stimulatory action was 2-fold

lower for PARP2. It is noteworthy that under our experimental conditions, the HPF1-PARP2 was more active in the heteroPARylation than in the automodification: about 80% of the total PAR was

bound to histones, at both the optimal and highly excessive HPF1 concentrations, while the maximal relative level of PARP1-catalyzed histone PARylation did not exceed 40% (Fig. 2e, f). The

specific function of PARP2 to modify predominantly histones was further evidenced from comparison of the initial rates of PARP1/PARP2-catalyzed auto- and heteromodification reactions (Table

1). PARP2 can therefore play a key role in the subsequent chromatin decompaction necessary for the recruitment of DNA repair factors to the damage sites. This idea is supported by the data

of Bilokapic’s work on the ability of the PARP2-HPF1 complex to retain two nucleosomes located near the DSB29, consistent with observations that PARP2 persists longer than PARP1 at DNA

damage sites16,18,44. Taking into account a transient direct (not DNA-mediated) interaction of PARP2 with HPF122, we explored the HPF1-induced modulation of the PARP1/2 activity in the

absence of DNA. Absence of statistically significant difference between PARP1 and PARP2 in the initial rates of DNA-independent automodification, in the absence and presence of HPF1 (Fig.

4c; Table 1), provides evidence that their basal activities are immediately related to the conserved catalytic domain and can be enhanced to some extent by the direct interaction with HPF1.

We have shown that only a large excess of HPF1 over PARPs can switch the activities of enzymes from PAR synthesis to NAD+ hydrolysis. This fact is in agreement with the published data also

obtained at the high HPF1 concentration31. However, our experiments at various HPF1 concentrations revealed no enhancement of the NAD+-hydrolase activity at the low HPF1 concentration,

optimal for stimulation of the PARPs activity in the automodification reaction (Fig. 6c, d). The switch of PARP1 to the NAD+-hydrolase activity persists in E284A-mutation of HPF1: the mutant

binds to the PARP1-nucleosome complex, but does not promote heteroPARylation of histones31. The authors suggest that the inhibitory effect of HPF1 on synthesis of PAR cooperates with the

switch of PARP1 activity to NAD+ hydrolysis. This effect results from shielding of the PARP1 elongation center in the complex with HPF1. As a result, PARP1, still associated with activating

DNA, quickly runs out of suitable PARylation sites and uses water as a nucleophile instead31. We assume that only complete binding of PARP to HPF1, which can be achieved at the large excess

of the cofactor, can promote switch to the NAD+-hydrolase activity. However, the cellular HPF1 concentration was shown to be significantly lower than that of PARP121. The concentrations of

HPF1 determined to be optimal for stimulating the PARPs automodification are comparable with those of PARPs, thus insuring coexistence of the HPF1-PARP complex with free PARP, which can

provide sites available for PARylation (Fig. 7a). Taken together, our data allow suggesting the following model of HPF1-dependent stimulation of PARP1/2: the DNA-bound PARP subunit (1) forms

a joint active site with HPF1 (2). The HPF1-free PARP subunit (3) interacts with this complex and serves as a PAR-acceptor. The PARP-HPF1 complex is involved in early stages of

serine-specific PARylation, which occurs with a high initial rate. The acceptor PARP subunit is PARylated and then substituted by the unPARylated HPF1-free PARP (4); this results in an

increased turnover of the whole process. At the same time, the HPF1-free PARP molecules (5) can be non-serine specifically PARylated with a lower initial rate but with a higher elongation

level. The high initial rate of HPF1-dependent reaction and presence of the unPARylated PARP excess lead to an increase in the number of acceptor sites, fast turnover of PARPs and removal of

the reaction product (due to dissociation of PARylated molecules). Finally, this results in increasing the total level of protein ADP-ribose incorporation. Data obtained previously22,24,34

and here under different experimental conditions provide evidence that HPF1 can promote opposite effects on distinct stages of the PARP1- and PARP2-catalyzed reaction: it stimulates early

stages and inhibits elongation by shielding of amino acid residues important for PAR chain elongation22. Thus, HPF1 can produce different effects on the overall PAR synthesis at low and high

NAD+ concentrations (Fig. 7b). Probably, at low NAD+ concentrations the initiation has the greatest contribution to the total reaction output, and the HPF1-induced stimulation of early

stages should significantly increase the level of protein-bound ADP-ribose. In contrast, at high NAD+ concentrations, the elongation has a predominant contribution to PAR synthesis. The

inhibitory action of HPF1 on the elongation step may therefore suppress the PARylation level at higher NAD+ concentrations. Thus, the hyperactivation of PARP in PAR synthesis at high NAD+

concentrations is inhibited by HPF1. At low NAD+ concentrations, the activity of PARP is stimulated by HPF1, with the optimal concentration and extent of stimulation being dependent on the

relative amounts of DNA-free and DNA-bound PARP. The dual regulatory function of HPF1 may contribute to maintenance of PARP activity at the level required for its function in the DNA damage

response signaling and repair, independently on the NAD+ concentrations. The suppression is most likely predominant function of HPF1 at the normal NAD+ concentration in the nucleus (100

μM45) to prevent negative consequences of PARP hyperactivation. The stimulatory action of HPF1 might regulate PARP activity under stressed conditions, when the sustained PARP activity leads

to NAD+ depletion. MATERIALS AND METHODS MATERIALS Recombinant wild-type human PARP1 and murine PARP2 were expressed and purified as described in detail previously46. Core histones were

isolated from _Gallus gallus_ erythrocytes and purified as described previously47. DNA primers for synthesis of Widom603 147 bp DNA and oligonucleotides for preparation of model 31 bp DNA

were synthesized in the Laboratory of Biomedicinal Chemistry (ICBFM SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia). pGEM-3z/603 was a gift from J. Widom (Addgene plasmid #26658; http://n2t.net/addgene:26658;

RRID: Addgene_26658). Proteinase K was purchased from Applichem (USA), DNase I was purchased from Thermo Scientific (USA). The 32P-labelled NAD+ was synthesized enzymatically according to

method described48, using [α-32P]ATP (with specific activity of 3000 Ci/mmol, synthesized in the Laboratory of Biotechnology, ICBFM, Novosibirsk, Russia). NAD+, NH2OH, reagents for

electrophoresis and basic components of buffers were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (USA). PREPARATION OF DNA AND NUCLEOSOME The sequences of the oligonucleotides for model DNA were as

follows: template—5′-GGAAGACCCTGACGTTCCCAACTTTATCGCC-3′, downstream primer—5′-pAACGTCAGGGTCTTCC-3′, upstream primer—5′-GGCGATAAAGTTGGG-3′. The model 31 bp DNA containing nick was prepared by

annealing the upstream primer and the downstream primer to the template. The mixture was heated at 90 °C and stepwise cooled to 40 °C, incubated for 15 min and cooled to 4 °C. The

effectiveness of hybridization was checked by PAGE in nondenaturing conditions. The amplification of Widom603 147 bp DNA and subsequent reconstitution of nucleosomes using the Widom603

sequence49 were performed as described previously47. Briefly, DNA was obtained by PCR (upstream primer—5′-ACCCCAGGGACTTGAAGTAATAAGG-3′; downstream primer—5′-CCCAGTTCGCGCGCCCACC-3′);

nucleosome was reconstructed by dialysis of DNA-histones mixture against a gradient of NaCl from 2 M to 10 mM. The homogeneity of the nucleosome sample was analyzed by the electrophoretic

mobility shift assay on a 4% nondenaturing PAG. HPF1 CLONING, EXPRESSION, AND PURIFICATION To obtain recombinant human HPF1 by expression in _E. coli_ cells, a plasmid was constructed. The

HPF1-coding sequence was amplified by PCR using specific primers and total HeLa cDNA. The resulting PCR product was annealed with the linearized pLate31 vector (Thermo Scientific, USA). The

amplified DNA plasmid was characterized by the Sanger sequencing method at the SB RAS Genomics Core Facility (ICBFM SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia). Next, _E. coli_ Rosetta (DE3) cells were

transformed with the pLate31-HPF1 plasmid. The transformed cells were incubated in a Studier autoinduction system in a 1 l of culture. The growth was carried out for 18 h at 18 °C. Further,

cells were harvested and lysed, and the HPF1 protein was purified by sequential chromatographies on the Ni-NTA agarose column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, USA), MonoQ 5/50 column (GE

Healthcare Life Sciences, USA), and Superdex 16/600 column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, USA). The protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically, using the adsorption

coefficient of the protein based on the Expasy Protparam Data. TESTING OF PARP ACTIVITY IN THE POLY(ADP-RIBOSE) SYNTHESIS Catalyzed by PARP1 and PARP2 autopoly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and covalent

labelling of histones were carried out in a standard 10 μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 µM [32P]NAD+ (or varied NAD+ concentrations

specified in Figure legends), 250 nM DNA (nucleosome), 500 nM PARP1 (PARP2), and 0.06‒16 μM HPF1. When indicated, the reaction mixture contained no DNA. The reaction was initiated by adding

[32P]NAD+ to a protein-DNA mixture preassembled on ice. After incubating the mixtures at 37 °C for 15 min for PARP1 and 45 min for PARP2, the reactions were terminated by the addition of

SDS-PAGE sample buffer and heating for 3 min at 95 °C. Where indicated, reactions were treated with 1 M hydroxylamine (NH2OH, pH 7.5) for 1 h at 37 °C before addition of loading buffer. The

reaction products were separated by 10% (20%) SDS-PAGE (a ratio between acrylamide and bis-acrylamide of 99:1); bands of proteins labelled with [32P]ADP-ribose were analyzed by using the

Typhoon imaging system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and Quantity One Basic software (Bio-Rad). The radiolabelled signals of modified proteins were quantified as follows: the total (raw)

signal of the smeared band of modified protein (indicated for each protein in the autoradiograms) was quantified and the same-size background signal of gel in the respective lane was

subtracted from the raw signal. The quantitative data presented in histograms were obtained in at least three independent experiments. KINETIC MEASUREMENTS OF PARP ACTIVITY

PARP1/PARP2-catalyzed reaction was carried out in a 70 μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 µM or 10 µM [32P]NAD+, 250 nM nucleosome, 500 nM PARP1

(PARP2), and 1 µM (for PARP1) or 0.5 μM (for PARP2) HPF1. Reactions were initiated by addition NAD+ (5 µl) and stopped by dispensing 5 µl aliquot of the mixture to the SDS-PAGE sample

buffer, using Multipette E3 dispenser (Eppendorf) for the repetitive dispensing every 10 seconds (until first 60 s of the reaction); the aliquots of longer incubation were dispensed

manually. TESTING OF NAD+-HYDROLASE ACTIVITY OF PARPS The reaction of NAD+ hydrolytic consumption catalyzed by PARP1 and PARP2 was carried out in a standard 10 μl reaction mixture containing

50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 µM [32P]NAD+, 250 nM nucleosome, 500 nM PARP1 (PARP2), and two different concentration of HPF1: 1 µM (for PARP1) or 0.5 μM (for PARP2), and

16 μM. After incubating the mixtures at 37 °C for 15 min for PARP1 and 45 min for PARP2, the reactions were terminated by the addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and heating for 3 min at 95

°C. The reaction products (covalently bound to PARP1/2 ADP-ribose, unconsumed NAD+ and free ADP-ribose) were separated by 20% SDS-PAGE (a ratio between acrylamide and bis-acrylamide of 99:1)

and their yields was analysed by phosphorimaging and quantified as described in the subsection “Testing of PARP activity in the poly(ADP-ribose) synthesis”. The quantitative data presented

in histograms were obtained in three independent experiments. STATISTICS AND REPRODUCIBILITY All experiments were repeated three times. Data are presented as mean values ± SD. The _t_-test

was used for the statistical analysis. Significant levels are: *_p_ < 0.05; **_p_ < 0.01; ***_p_ < 0.001. REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in

the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article. DATA AVAILABILITY The pLate31-HPF1 plasmid constructed for cloning and expression of recombinant human HPF1 protein has been

deposited into the database at https://www.addgene.org/; the accession number is Plasmid #176513. Uncropped autoradiograms are provided in the Supplementary Data file. Source data underlying

the graphs and charts presented in the figures are available in the Supplementary Data. All other related data will be available upon reasonable request. REFERENCES * Crawford, K.,

Bonfiglio, J. J., Mikoc, A., Matic, I. & Ahel, I. Specificity of reversible ADP-ribosylation and regulation of cellular processes. _Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol._ 53, 64–82 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Spiegel, J. O., Van Houten, B. & Durrant, J. D. PARP1: Structural insights and pharmacological targets for inhibition. _DNA Repair (Amst.)_ 103,

103125 (2021). Article CAS Google Scholar * Schreiber, V., Dantzer, F., Ame, J. C. & de Murcia, G. Poly(ADP-ribose): novel functions for an old molecule. _Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol._

7, 517–528 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pascal, J. M. & Ellenberger, T. The rise and fall of poly(ADP-ribose): an enzymatic perspective. _DNA Repair (Amst.)_ 32, 10–16

(2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Amé, J. C. et al. PARP-2, a novel mammalian DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. _J. Biol. Chem._ 274, 17860–17868 (1999). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Hanzlikova, H., Gittens, W., Krejcikova, K., Zeng, Z. & Caldecott, K. W. Overlapping roles for PARP1 and PARP2 in the recruitment of endogenous XRCC1 and PNKP

into oxidized chromatin. _Nucleic Acids Res_. 45, 2546–2557 (2017). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hoch, N. C. & Polo, L. M. ADP-ribosylation: from molecular mechanisms to human disease.

_Genet. Mol. Biol._ 43, e20190075 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Sukhanova, M. V. et al. A single-molecule atomic force microscopy study of PARP1 and PARP2

recognition of base excision repair DNA Intermediates. _J. Mol. Biol._ 431, 2655–2673 (2019). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Eisemann, T. & Pascal, J. M. Poly(ADP-ribose)

polymerase enzymes and the maintenance of genome integrity. _Cell. Mol. Life Sci._ 77, 19–33 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Vasil’eva, I., Moor, N., Anarbaev, R., Kutuzov,

M. & Lavrik, O. Functional roles of PARP2 in assembling protein-protein complexes involved in base excision DNA repair. _Int. J. Mol. Sci._ 22, 4679 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed

Central CAS Google Scholar * Ménissier de Murcia, J. et al. Functional interaction between PARP-1 and PARP-2 in chromosome stability and embryonic development in mouse. _EMBO J._ 22,

2255–2263 (2003). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Khodyreva, S. N. & Lavrik, O. I. Poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase 1 as a key regulator of DNA repair. _Mol. Biol. (Mosk.)_

50, 655–673 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lavrik, O. I. PARPs’ impact on base excision DNA repair. _DNA Repair (Amst.)_ 93, 102911 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Caldecott, K. W. Mammalian DNA base excision repair: dancing in the moonlight. _DNA Repair (Amst.)_ 93, 102921 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sukhanova, M., Khodyreva, S. &

Lavrik, O. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 regulates activity of DNA polymerase beta in long patch base excision repair. _Mutat. Res._ 685, 80–89 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Kutuzov, M. M. et al. Interaction of PARP-2 with DNA structures mimicking DNA repair intermediates and consequences on activity of base excision repair proteins. _Biochimie_ 95, 1208–1215

(2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kutuzov, M. M., Belousova, E. A., Ilina, E. S. & Lavrik, O. I. Impact of PARP1, PARP2 & PARP3 on the base excision repair of

nucleosomal DNA. _Adv. Exp. Med. Biol._ 15, 47–57 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kutuzov, M. M. et al. The contribution of PARP1, PARP2 and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation to base excision

repair in the nucleosomal context. _Sci. Rep._ 11, 4849 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sukhanova, M. V. et al. Single molecule detection of PARP1 and PARP2

interaction with DNA strand breaks and their poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation using high-resolution AFM imaging. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 44, e60 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, Q. et al.

PARP2 mediates branched poly ADP-ribosylation in response to DNA damage. _Nat. Commun._ 9, 3233 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Gibbs-Seymour, I., Fontana,

P., Rack, J. G. M. & Ahel, I. HPF1/C4orf27 Is a PARP-1-interacting protein that regulates PARP-1 ADP-ribosylation activity. _Mol. Cell._ 62, 432–442 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Suskiewicz, M. J. et al. HPF1 completes the PARP active site for DNA damage-induced ADP-ribosylation. _Nature_ 579, 598–602 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Bonfiglio, J. J. et al. Serine ADP-ribosylation depends on HPF1. _Mol. Cell_ 65, 932–940 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sun, F. H.

et al. HPF1 remodels the active site of PARP1 to enable the serine ADP-ribosylation of histones. _Nat. Commun._ 12, 1028 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Palazzo, L. et al. Serine is the major residue for ADP-ribosylation upon DNA damage. _Elife_ 7, e34334 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Langelier, M. F., Planck, J.

L., Roy, S. & Pascal, J. M. Structural basis for DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by human PARP-1. _Science_ 11, 728–732 (2012). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Dawicki-McKenna, J. M. et al. PARP-1 activation requires local unfolding of an autoinhibitory domain. _Mol. Cell_ 60, 755–768 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Steffen, J. D., McCauley, M. M. & Pascal, J. M. Fluorescent sensors of PARP-1 structural dynamics and allosteric regulation in response to DNA damage. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 44, 9771–9783

(2016). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bilokapic, S. et al. Bridging of DNA breaks activates PARP2–HPF1 to modify chromatin. _Nature_ 585, 609–613 (2020). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ogden, T. E. H. et al. Dynamics of the HD regulatory subdomain of PARP-1; substrate access and allostery in PARP activation and inhibition. _Nucleic

Acids Res._ 26, 2266–2288 (2021). Article CAS Google Scholar * Rudolph, J., Roberts, G., Muthurajan, U. M. & Luger, K. HPF1 and nucleosomes mediate a dramatic switch in activity of

PARP1 from polymerase to hydrolase. _Elife_ 10, e65773 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Prokhorova, E. et al. Unrestrained poly-ADP-ribosylation provides

insights into chromatin regulation and human disease. _Mol. Cell_ 81, 2640–2655 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rudolph, J., Roberts, G. & Luger, K.

Histone parylation factor 1 contributes to the inhibition of PARP1 by cancer drugs. _Nat. Commun._ 12, 736 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gaullier, G. et al.

Bridging of nucleosome-proximal DNA double-strand breaks by PARP2 enhances its interaction with HPF1. _PLoS ONE_ 15, e0240932 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Desmarais, Y., Ménard, L., Lagueux, J. & Poirier, G. G. Enzymological properties of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase: characterization of automodification sites and NADase activity. _Biochim.

Biophys. Acta_ 24, 179–186 (1991). Article Google Scholar * Lindahl, T., Satoh, M. S., Poirier, G. G. & Klungland, A. Post-translational modification of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

induced by DNA strand breaks. _Trends Biochem. Sci._ 20, 405–411 (1995). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Schreiber, V. et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-2 (PARP-2) is required for

efficient base excision DNA repair in association with PARP-1 and XRCC1. _J. Biol. Chem._ 21, 23028–23036 (2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gagné, J. P. et al. Quantitative proteomics

profiling of the poly(ADP-ribose)-related response to genotoxic stress. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 40, 7788–77805 (2012). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Jungmichel, S. et

al. Proteome-wide identification of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation targets in different genotoxic stress responses. _Mol. Cell_ 52, 272–285 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Alemasova,

E. E. & Lavrik, O. I. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP1: reaction mechanism and regulatory proteins. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 47, 3811–3827 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Maltseva, E. A., Krasikova, Y. S., Sukhanova, M. V., Rechkunova, N. I. & Lavrik, O. I. Replication protein A as a modulator of the poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1

activity. _DNA Repair (Amst.)_ 72, 28–38 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Naumenko, K. N. et al. Regulation of poly(ADP-rbose) polymerase 1 activity by Y-box-binding protein 1.

_Biomolecules_ 16, 1325 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ruf, A., de Murcia, G. & Schulz, G. E. Inhibitor and NAD+ binding to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase as derived from crystal

structures and homology modeling. _Biochemistry_ 37, 3893–3900 (1998). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Langelier, M. F., Riccio, A. A. & Pascal, J. M. PARP-2 and PARP-3 are

selectively activated by 5’ phosphorylated DNA breaks through an allosteric regulatory mechanism shared with PARP-1. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 42, 7762–7775 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Cambronne, X. A. et al. Biosensor reveals multiple sources for mitochondrial NAD+. _Science_ 352, 1474–1477 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Amé, J. C., Kalisch, T., Dantzer, F. & Schreiber, V. Purification of recombinant poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases. _Methods Mol. Biol._ 780, 135–152 (2011). Article PubMed CAS

Google Scholar * Kutuzov, M. M., Kurgina, T. A., Belousova, E. A., Khodyreva, S. N. & Lavrik, O. I. Optimization of nucleosome assembly from histones and model DNAs and estimation of

the reconstitution efficiency. _Biopolym. Cell_ 35, 91–98 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Moor, N. A., Vasil’eva, I. A., Kuznetsov, N. A. & Lavrik, O. I. Human apurinic/apyrimidinic

endonuclease 1 is modified in vitro by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 under control of the structure of damaged DNA. _Biochimie_ 168, 144–155 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Lowary, P. T. & Widom, J. J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. _Mol. Biol._ 276, 19–42 (1998). Article

CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the entire laboratory of bioorganic chemistry of enzymes for feedback. We acknowledge Ekaterina A. Belousova

for supporting initial stages of this work, and Svetlana N. Khodyreva for guidance in obtaining NCP. The reported study was funded by RFBR according to the research projects № 20-34-70028

(protein purification) and № 20-34-90095 (DNA and nucleosome construction), by RSFP № 121031300041-4 (use of shared equipment for experimental work), and by RSF № 21-64-00017 (PARPs activity

testing in various conditions). AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Tatyana A. Kurgina, Nina A. Moor. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Institute of Chemical

Biology and Fundamental Medicine, SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia Tatyana A. Kurgina, Nina A. Moor, Mikhail M. Kutuzov, Konstantin N. Naumenko, Alexander A. Ukraintsev & Olga I. Lavrik *

Novosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk, Russia Tatyana A. Kurgina & Olga I. Lavrik Authors * Tatyana A. Kurgina View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Nina A. Moor View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mikhail M. Kutuzov View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Konstantin N. Naumenko View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Alexander A. Ukraintsev View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Olga I. Lavrik View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS

T.A.K. performed the experiments and created the figures. N.A.M. and O.I.L. designed the study. M.M.K., K.N.N., and A.A.U. contributed to the study with protein purification and nucleosome

assembling. T.A.K., N.A.M., and O.I.L. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Correspondence to Olga I. Lavrik. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Communications Biology_

thanks Edoardo Longarini, Ivan Matic and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Eve Rogers. Peer reviewer reports

are available. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION TRANSPARENT

PEER REVIEW FILE SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION DESCRIPTION OF ADDITIONAL SUPPLEMENTARY FILES SUPPLEMENTARY DATA 1 REPORTING SUMMARY RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate

credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article

are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and

your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this

license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Kurgina, T.A., Moor, N.A., Kutuzov, M.M. _et al._ Dual function of

HPF1 in the modulation of PARP1 and PARP2 activities. _Commun Biol_ 4, 1259 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02780-0 Download citation * Received: 02 June 2021 * Accepted: 01

October 2021 * Published: 03 November 2021 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02780-0 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative