- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Templer, V.L., Wise, T.B., and Heimer-McGinn, V.R. _Neurobiol Aging_ 75, 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.11.016 So you want to study aging. If you’re working with

rodents, it might be relatively easy to order up a batch of animals—some young, some old—to compare and contrast against each other. That’s quicker and easier than waiting for them to age

naturally at your own facility, and the animals will be experimentally naive; no need to worry about any lingering effects from prior testing. But if the goal of using those animals is to

understand the aging process or any one of its many complications in humans, such cross-sectional approaches are not necessarily the most reflective of the human experience. Aging is an

individual process, influenced by decades of prior experience. To really understand it, it’s important to consider variability within individuals and changes that occur over time too. For

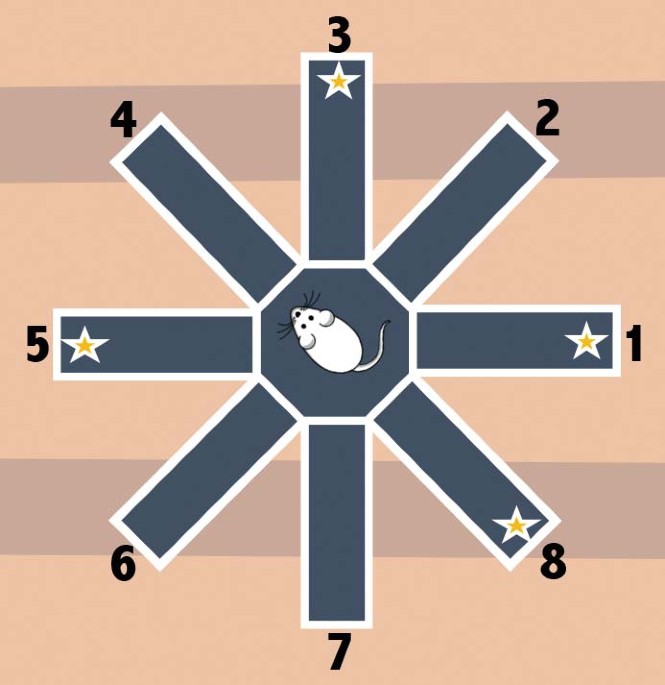

the study, an 8-arm radial arm maze was baited the same way at each of the three testing points. Picking an unbaited arm represented a reference memory error; forgetting which arms were

already visited represented a working memory error. Adapted with permission from Templer et al. (2018) Elsevier. That’s how Victoria Templer, a behavioral & cognitive neuroscientist at

Providence College in Rhode Island, has approached her research with rats. In a recent study published in the journal _Neurobiology of Aging_, she and her lab took a longitudinal look at the

effects of social housing on memory in male Long Evans rats as they aged. All the animals spent their lives living in enriched conditions. Enrichment is known to have a protective effect

against age-related cognitive decline in rodents, but the contribution of long-term social interactions with conspecifics hadn’t been entirely teased out from that of physical enrichment.

From the time they arrived in Providence at just 21 days old, half of the animals were socially housed while the other ten spent their days environmentally enriched but isolated from other

rats. Templer and her lab repeated tests of short-term working memory and long-term reference memory with each rat in a radial arm maze three times over the course of their natural

lifespans: as 10-month old adults, as they reached middle age at 16 months, and as old rats just shy of two years old. Reference memory, which is the ability to recall a prior learned

task—in this case, which arms of the maze were baited with a treat—did not appear to be affected by housing: errors declined slightly in middle age, a reflection of prior practice, before

ticking up at the final testing point in both social and individually housed animals. Working memory, however, took a hit—at old age, rats that had been housed alone made significantly more

working memory errors than their socially enriched counterparts. “They were going back down an arm that they already went down,” says Templer, forgetting what they had already done. Think of

an elderly person trying to remember whether they took their medication or brushed their teeth. The study suggests that social interactions confer a protective effect against working memory

loss in aging rats, says Templer. She and her collaborators plan to follow this behavioral study up by looking more closely at what’s happening in the rats’ brains—are there differences in

brain volume or neurogenesis in the socially housed animals that might explain the memory outcomes? “I would be very surprised if we didn’t see differences in the brains of these animals,”

she says. The longitudinal approach Templer took was a somewhat unconventional one, at least in the realm of rat research where cross-sectional comparisons tend to be more common. But prior

to starting her lab at Providence, Templer worked with macaques. It takes a nonhuman primate a long time to get old—two to three decades, compared to the two or three years of the average

rat lifespan—and opportunities to experimentally manipulate and study their neurobiology are challenging relative to smaller animals. So she made the switch to rodents, leaving macaques

behind but not necessarily the experimental design approaches that are _de riguer_ for working with them. Rodent researchers may worry about confounding effects of testing the same animal

repeatedly, but that’s normal in nonhuman primate research. Individual animals are generally used multiple times, with prior testing disclosed in subsequent publications. When making

comparisons between groups of animals that share the same prior experiences, as the rats did in the current study, those prior experiences themselves shouldn’t be the accounting factor for

any differences observed. Logistically, it is more involved to house rats over their entire lifespans than just ordering the necessary age group—particularly in the enriched conditions

Templer used for the current study. The rats lived in ferret cages, outfitted with running wheels, tunnels and platforms, and a variety of chew toys. “It was like housing 20 pets rather than

your typical lab animal,” she says. Being at small college without full-time animal care staff meant that keeping the rats happy and healthy was up to Templer and her students and lab

manager. But the longitudinal approach has advantages that it make it worth the extra husbandry time: it provides a better model of human behavior. “Humans don’t just exist and are tested

for the first time on something when they’re 50 years old,” Templer says. They’ve been doing things their entire lives. Plus, subjects vary, whether human or rodent; longitudinal designs can

take differences in individuals into account. “Being able to maintain some of that individuality and do analyses that speak to that can actually be helpful in quantifying why types of

cognitive effects are changing over time,” she says. And in the end, with fewer rats needed. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Lab Animal http://www.nature.com/laban/ Ellen P.

Neff Authors * Ellen P. Neff View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Ellen P. Neff. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS

Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Neff, E.P. Go long(-itudinal)! Social housing protects working memory in rats. _Lab Anim_ 48, 81 (2019).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41684-019-0245-6 Download citation * Published: 04 February 2019 * Issue Date: March 2019 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41684-019-0245-6 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone

you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the

Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative