- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT This study examines the relationship between foreign direct investment and total factor productivity on economic growth in 90 middle-income countries. Because middle-income

countries often face particular challenges in achieving sustainable economic development. Investigating how FDI and TFP contribute to or hinder economic growth in these countries can provide

insight and help policymakers make policy decisions. We employ the dynamic system Generalized Method of Moments to analyze an unbalanced sample with 2714 annual observations from 1990 to

2020. The empirical results show that a percentage increase in foreign direct investment will increase economic growth in middle-income countries by 9.3%. In addition, Total Factor

Productivity also has a positive relationship with economic growth due to improved labor quality and production innovations. Furthermore, the results indicate that Total Factor Productivity

empowers the positive nexus between Foreign Direct Investment and economic growth. In addition, the main findings are also robust even though we employ alternative economic growth proxies.

These findings support economic growth and industrialization theories but do not support labor market dynamics theories. Finally, this study contributes practical suggestions for sustainable

economic development in middle-income countries. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS HOW DOES INTER-PROVINCIAL TRADE PROMOTE ECONOMIC GROWTH? EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE FROM CHINESE PROVINCES

Article Open access 02 August 2024 A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF INVESTMENT INDICATORS AND ECONOMIC GROWTH IN NIGERIA Article Open access 11 August 2023 THE DYNAMIC RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRADE

OPENNESS, FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, CAPITAL FORMATION, AND INDUSTRIAL ECONOMIC GROWTH IN CHINA: NEW EVIDENCE FROM ARDL BOUNDS TESTING APPROACH Article Open access 11 April 2023 INTRODUCTION

Among the 17 sustainable development objectives set forth by the UN, sustainable economic growth is Sustainable Development Goal 8 (SDG8) (Rai et al., 2019). Economic growth creates many

new job opportunities and improves people’s living standards. It creates opportunities to increase people’s income and reduce poverty. Economies are accumulating financial resources to

invest in technology, infrastructure, education, research, and development. In addition, industrialization is gradually changing in the current global context, so economic growth also

creates opportunities to expand exports and attract foreign investment to develop domestic economic sectors or generate revenue for the state budget (Balsa-Barreiro et al., 2019). This

revenue source supports the government’s investment in public projects and improves public services and social support (Nistor, 2014). Consequently, it is essential to research how total

factor productivity (TFP) and foreign direct investment (FDI) affect economic growth. Sustainable economic development is the general objective of all countries. Improving economic

efficiency and productivity in developing countries requires attracting foreign direct investment (Agrawal and Khan, 2011). Sokang (2018) shows that foreign direct investment (FDI) can solve

capital shortages, improve technology, and positively impact economic growth. Saleem et al. (2019) argue that total factor productivity (TFP) promotes the economy when workers’

qualifications are improved or new human resources are trained. Baltabaev (2014) argues that the interaction of FDI and TFP increases GDP through capital injection and technology transfer,

improving local business production processes. On the other hand, Sabir et al. (2019) found a negative correlation coefficient between foreign direct investment (FDI) and economic

development. This is because FDI causes a trade deficit by increasing imports, delaying domestic exports, and reducing manufacturing activity. Almfraji and Almsafir (2014) believe that

increased FDI will cause a deficit in domestic investment capital and difficulties using domestic capital, causing economic recession. The Solow productivity paradox indicates that the

technological coincidence between countries leads to a gradual decrease in labor productivity gaps between countries and slows economic growth (Chen and Xie, 2015). Arslan (2016) argues that

the fact that most economies are urban promotes agglomeration and economic diversity. However, Wang et al. (2021) conclude that concentrating FDI in specific industries or economic sectors

can lead to weakening the diversity and competition of other industries, causing overreliance on FDI and influencing negative economic growth. This study contributes to the growing

literature on sustainable development goals in the following ways. First, previous studies such as Sokang (2018), Sabir et al. (2019), Saleem et al. (2019), Chen and Xie (2015), and

Baltabaev (2014) focus mainly on the role of FDI and TFP as independent factors in the model without considering the interaction between FDI and TFP on economic growth in middle-income

countries with economic structures different economies including emerging markets, industrialized economies and countries in transition. Therefore, the first research question is whether or

not the interaction role between FDI and TFP positively impacts GDP. Second, previous studies show that economic factors impact countries with different economic structures in different

periods. This study will be based on data from middle-income countries, as middle-income countries include a variety of economic structures, industries, and stages of development. Studying

FDI and TFP in these countries allows researchers to examine their effects across various contexts, including emerging markets, industrialized economies, and transitioning countries. This

diversity provides valuable insights into the impact of FDI and TFP on economic growth and facilitates the identification of specific factors driving these relationships. Besides, many

middle-income countries are transitioning from low to high income, undergoing structural transformation, and facing economic challenges related to growth, competitiveness, and sustainable

development. Researching FDI and TFP in these countries sheds light on the dynamics of economic transition and the role of external and internal factors in promoting growth and development

to inform policy decisions to promote inclusive and sustainable development. This study examines the economic growth of middle-income economies as they seek to support their economic

development (Balsa-Barreiro et al., 2022). The second research question is whether the prior findings from developed or low-income nations remain robust in middle-income countries.

Specifically, we used the World Bank database to gather data from 90 middle-income nations between 1990 and 2020. Furthermore, we employ the dynamic system generalized method of moments

(GMM) with cross-section fixed effects to address endogeneity issues. Finally, this study performs two tests to ensure robust findings. Specifically, the first test examines whether the main

findings are robust after employing alternative economic growth proxies. The second test analyzes whether the findings are robust before and after the financial crisis. Our empirical

results suggest that FDI has a positive impact on economic growth. FDI helps expand the market, expand production scale, and increase local businesses' access to more advanced

technology (Sokang, 2018). Our findings conclude that TFP promotes economic growth. This finding is consistent with Bal and Rath (2014). In addition, the interaction of FDI and TFP

positively correlates with GDP in middle-income countries. Our results are consistent with those of Ahmed (2012), who states that FDI increases technology transfer between countries and

contributes to the training and development of human resources in recipient countries, thereby enhancing productivity and efficiency in production. The remainder of this article is

structured as follows: Section “Literature review” deals with a literature review; Section “Data and methodology” will present sample data and research methods; Section “Empirical results”

will present the estimated results of the study; Section “Discussion” presents discussion; Section “Conclusion” summarizes the study’s conclusions, and Section “Limitation and implication”

provides limitation and practical implications based on the findings. LITERATURE REVIEW THEORIES ECONOMIC GROWTH THEORIES Economic growth is a criterion to measure the economic development

of a country. It can be measured as an increase in gross domestic product (GDP) and gross domestic product per capita based on purchasing power parity or the size of national output per

capita (PCI) or gross national product (GNP) in each period (Lewis, 2013; Adewole, 2012). Economic growth describes the quantitative change in a country’s economy. GDP is one of the leading

indicators to assess the overall growth rate of the economy as well as the level of development of a country. Most countries use some of their GDP of GNP to measure their economic growth.

Economic growth reflects very clearly the actual status of a country’s output or product in the economy and each economic region, based on which countries will make applicable policies for

economic development. Enterprises also rely on it to make more accurate decisions. Nistor (2014) proves that FDI has a positive effect on economic development because FDI has a role in

increasing domestic investment. As FDI increases, it increases export activities, promotes the transfer of goods and services, or increases access to technology, increasing GDP. Besides, TFP

also positively impacts economic growth because TFP reflects the efficiency of capital and human resources used in production. When TFP increases, it will help improve the results of

production activities and input-output, which is very important for the economy; businesses will also rely on it to expand their production capacity and increase GDP (Arazmuradov et al.,

2014). Therefore, economic growth theories expect that FDI and TFP positively impact GDP growth. INDUSTRIALIZATION THEORIES Industrialization theory suggests that an agriculture-based

economy is transforming toward an industrial-based economy. According to this theory, industry is essential to economic and social development. It focuses on strengthening industrial

production, improving technology, improving labor productivity, increasing TFP, and helping economic growth (Zhan et al., 2022). While countries can transition toward a digital economy

without industrialization, developed countries are decentralizing part of their industry (Balsa-Barreiro et al., 2023); industrialization can bring many benefits, such as creating jobs,

increasing income, improving quality of life, and overall economic development. According to Nursamsu and Hastiadi (2015), industrialization theory suggests that economies can increase their

TFP by improving production technology, production management and organization, human resource qualifications, scale production, and contributing to economic development. In addition,

industrialization enhances investment attraction, provides human resources to expand markets, and creates favorable economic growth conditions (Megbowon et al., 2019). Therefore,

industrialization theories expect that FDI and TFP positively affect economic growth. LABOR MARKET DYNAMICS THEORIES Labor market dynamics theories explain how workers and employers interact

and influence each other in the labor market. According to Berrebi and Ostwald (2016), employees and employers have goals. Workers want to find jobs with high incomes and good working

conditions, while employers want to hire workers at low cost but with appropriate abilities and skills. Besides, it also affects local economic growth by attracting foreign direct investment

projects. According to Decreuse and Maarek (2015), labor market dynamics theories suggest that FDI projects may cause adverse effects on local employment, wages, and economic growth by

replacing local workers with foreign workers. Additionally, inefficient FDI projects may reduce local economic growth due to a lack of technological transfer and labor development (Omri and

Kahouli, 2014). In short, labor market dynamics theories suggest that FDI has mixed effects on economic growth. FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT AND ECONOMIC GROWTH Some previous studies suggest

that FDI has a positive impact on economic growth. Sokang (2018) suggests that FDI positively impacts economic growth because FDI helps expand production and increases access to more

advanced technology for local businesses. In addition, FDI also helps improve export output, supplement capital, increase capital efficiency, and create a large budget to promote economic

growth (Agrawal and Khan, 2011). However, some studies report a negative relationship between FDI and economic growth. Increasing FDI projects leads to a deficit in domestic investment

capital and difficulties using domestic capital and human resources, causing economic recession (Almfraji and Almsafir, 2014). Sabir et al. (2019) report that FDI may cause trade imbalance.

When import activities are higher than export activities, it will reduce employment, causing fewer goods to be produced, which can cause a trade deficit. Previous studies have shown that the

relationship between FDI and economic growth has positive and negative effects. Studies show that FDI positively correlates with economic growth using data samples from middle-income

countries such as China, India, and Cambodia (Sokang, 2018; Agrawal and Khan, 2011). In addition, there are also research articles using data samples from middle-income countries such as

Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador, but the main finding is that FDI hurts economic growth (Almfraji and Almsafir, 2014; Sabir et al., 2019). As previous studies report mixed findings

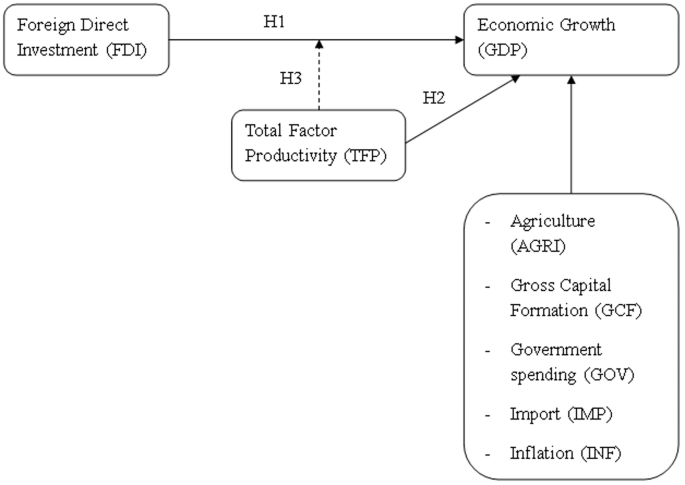

between FDI and economic growth in middle-income countries, we propose the following hypothesis: Hypothesis 1: FDI positively impacts economic growth in middle-income countries. TOTAL FACTOR

PRODUCTIVITY AND ECONOMIC GROWTH Saleem et al. (2019) argue that TFP positively impacts economic growth. Improving the qualifications of workers, training technology transfer, and

increasing the efficiency of capital use help increase total factor productivity to promote global economic growth. In addition, increased demand for goods and services leads to an increase

in export activities, which is the basis for optimizing resources or promoting product research and product development; production process improvement helps improve productivity, thereby

contributing to increasing TFP and promoting the country’s economic growth (Bal and Rath, 2014). Besides, the Solow productivity paradox (Chen and Xie, 2015) arises when there is

insufficient investment in technology and a shortage of skilled workers who can use new technology effectively. This trend can cause structural unemployment, where workers displaced by

automation may not have the skills needed in the emerging job market. This transition period can hinder economic growth as workers adjust to new job opportunities. TFP will slow down when

labor productivity decreases, leading to economic recessions (Chen and Xie, 2015). Moreover, higher productivity may lead to misallocation of resources. For example, if a country heavily

invests in one industry due to its high productivity potential but neglects other vital sectors, it could result in an imbalanced and unsustainable economic structure. Previous studies

report mixed findings between TFP and economic growth; we propose the following hypothesis: Hypothesis 2: TFP positively affects economic growth in middle-income countries. FOREIGN DIRECT

INVESTMENT AND TOTAL FACTOR PRODUCTIVITY Prior studies suggest that an interaction between FDI and TFP positively impacts economic growth. Ahmed (2012) reports that FDI has a positive

relationship with TFP because FDI increases technology transfer between countries and contributes to the training and development of human resources in recipient countries, improving labor

capacity and the quality of human resources, thereby improving productivity and efficiency in production. In addition, FDI also motivates local governments to develop local infrastructure

that helps improve production processes, and it also helps expand consumption markets, creating motivation for production growth (Baltabaev, 2014). Therefore, the interaction between FDI and

TFP positively impacts economic growth. However, other articles suggest that the interactive relationship between FDI and TFP negatively impacts economic growth. In some cases of FDI, not

all technologies are transferred into the local economy due to ineffective management, which reduces the rate of technology transfer. Inefficient technology transfer discourages driving

forces to develop local productivity. In addition, in some other cases, focusing FDI on specific industries or economic sectors can weaken the diversity and competition of other industries,

causing excessive dependence on FDI and adverse effects on TFP growth. Therefore, the interactive relationship between FDI and TFP hurts economic growth. As prior studies reported that the

interaction between FDI and TFP has mixed impacts on economic growth, we propose the following hypothesis: Hypothesis 3: The interaction between FDI and TFP positively affects economic

growth in middle-income countries. DATA AND METHODOLOGY DATA Based on the World Bank’s 2010 classification, there were 120 middle-income countries between 1990 and 2020. However, after

merging all TFP data sources, there are only data for 90 countries with an average gross national income per capita from $1026 to $12,475, classified as middle-income countries by the World

Bank. Appendix B reports the country list in this study. Data is collected from the World Bank to ensure creditability and accuracy. We followed Duong et al. (2022) and Tran et al. (2023) to

exclude observations that do not have data to account for variables. We follow Le et al. (2023) to winsorize all variables at the 5th and 95th percentiles to mitigate the outlier issues.

Our final data sample is an unbalanced panel, including 2714 annual observations from 1990 to 2020 from 90 middle-income countries. VARIABLE DEFINITIONS ECONOMIC GROWTH (GDP) GDP is a

country’s gross domestic product. According to Nistor (2014), high economic growth will make a country’s economy more stable, so an increase in gross domestic product is necessary. GDP is

measured using the market value approach and is calculated based on the total value of goods and services produced within a country during a given period. The market value represents the

price at which these goods and services are traded. This data is collected in the World Bank’s World Development Indicators section. FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT (FDI) FDI is a foreign direct

investment; we measure FDI by net direct investment inflow into a particular country over a total GDP (Sokang, 2018; Duong et al., 2022). THE TOTAL FACTOR PRODUCTIVITY (TFP) TFP is the total

factor productivity, which is measured by the efficiency of the production process when factors of production (human, capital, and technology) are used optimally (Miao et al., 2022).

Following Duong et al. (2022), Dettori et al. (2012), and Moghaddasi and Pour (2016), we calculate TFP based on the Cobb–Douglas function model as \(Y={{{\rm {TFP}}}}_{{it}}\times {K}^{\beta

}{\times L}^{\alpha }\). CONTROL VARIABLES Prior studies report that agriculture has a positive relationship with economic growth. According to Awokuse and Xie (2015), agriculture is a food

source that creates more jobs, contributes to production and economic development in rural areas, and helps the economy grow sustainably. Therefore, agricultural variables also have a

significant influence on economic growth. Pasara and Garidzirai (2020) found that GCF generates productivity and economic efficiency significantly. Investing in fixed assets improves labor

productivity, production capacity, and infrastructure, boosting economic growth. However, according to Sinha and Kalayakgosi (2018), the disparity in investment quality and when borrowing

costs are too high lead to the inability to access cheap capital and invest in fixed assets. Based on previous studies, we conjecture that the GCF variable significantly impacts economic

growth. According to Nurudeen and Usman (2010), government spending can stimulate the economy, educate and train human resources, and invest in new technology to promote economic growth.

However, Nyasha and Odhiambo (2019) show that inefficient GOV causes waste, loss of resources, and increased debt, negatively affecting economic growth. Therefore, the GOV variable has an

impact on economic growth. Ahmed et al. (2013) and Millia et al. (2021) show that imports will reduce domestic production and increase foreign debt, causing pressure on debt repayment and

interest rates negative for economic growth. Accordingly, the import variable is the variable that affects economic growth. Ayyoub et al. (2011) and Mwakanemela (2013) argue that inflation

will reduce the value of money and increase the price of raw materials and labor, leading to increased production costs, affecting competitiveness, and losing value income, thereby reducing

economic growth. Therefore, inflation has a significant impact on economic growth. MODEL CONSTRUCTIONS We follow the study by Agrawal and Khan (2011) to examine the positive relationship

between FDI and economic growth. However, Sabir et al. (2019) suggest that FDI hurts economic growth. Then we have regression model 1 as follows: $${{Model}}\,{\it{1}}:{{GD{P}}}_{i,t}=\alpha

+{\beta }_{\it{1}}{{FD{I}}}_{it}+{\beta }_{\it{2}}{{CONTRO{L}}}_{it}+{\alpha }_{i}+{\alpha }_{t}+{\varepsilon }_{i,t}$$ (1) In this study, we followed Saleem et al. (2019) to see the

positive impact of TFP on economic growth. Furthermore, a decrease in TFP also reduces economic growth according to the Solow productivity paradox (Chen and Xie, 2015; Wannakrairoj and Velu,

2021), and we have built model 2 as follows: $${{Model}}\,{\it{2}}:{{GD{P}}}_{i,t}=\alpha +{\beta }_{\it{1}}{{TF{P}}}_{it}+{\beta }_{\it{2}}{{CONTRO{L}}}_{it}+{\alpha }_{\it{i}}+{\alpha

}_{t}+{\varepsilon }_{i,t}$$ (2) Follow Fleisher et al. (2010) to study the impact of the independent variables FDI, TFP, and control variables on the dependent variable economic growth by

establishing model 3 as follows: $${{Model}}\,{\it{3}}:{{GD{P}}}_{i,t}=\alpha +{\beta }_{\it{1}}{{FD{I}}}_{it}+{\beta }_{\it{2}}{{TF{P}}}_{it}+{\beta }_{\it{3}}{{CONTRO{L}}}_{it}+{\alpha

}_{i}+{\alpha }_{t}+{\varepsilon }_{i,t}$$ (3) We follow Baltabaev (2014) to study the interaction between FDI and TFP and its positive impact on economic growth. On the other hand, we also

want to find out if the interaction between FDI and TFP has a negative impact on economic growth, according to the study of Wang et al. (2021). We propose the model 4 as follows:

$$\begin{array}{c}{{Model}}\,{\it{4}}:{{GD{P}}}_{i,t}=\alpha +{\beta }_{\it{1}} {FD{I}}_{it}+{\beta }_{\it{2}}{{TF{P}}}_{it}+{\beta }_{\it{3}}{{FDI}}\ast {{TF{P}}}_{it}\\ \,+\,{\beta

}_{\it{4}}{{CONTRO{L}}}_{it}+{\alpha }_{i}+{\alpha }_{t}+{\varepsilon }_{i,t}\end{array}$$ (4) where “_i_” is the cross-section, “_t_” is the time, and “_α_” is the constant. In addition,

CONTROL is the control variable. Appendix A reports all the variable definitions. Fig. 1 indicates the final research model as follows. ESTIMATION METHODOLOGY Our study employs a data panel

with 90 countries over 31 years (1990–2020), we perform the Hausman test (Shao et al., 2021) and the Redundant Fixed Effect test (Duong et al., 2022) to check whether ordinary least squares

(OLS), fixed effect model (FEM) and random effect model (REM) are suitable for each model. Then, we follow Le et al. (2023) and Duong et al. (2023) to perform the Wald test to check for

possible heterogeneity issues. In addition, we perform the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test for possible endogeneity. Endogeneity refers to a situation in which a variable in a statistical model is

correlated with the error term. This correlation can lead to biased and inefficient estimates of the model parameters. Endogeneity can be a particular concern in panel data regressions,

where observations are made on multiple entities over time. Some previous studies pioneered solving the endogeneity problem (Anderson and Hsiao, 1982) by combining the first difference

method with instrumental variables. Later, Arellano and Bond (1991) introduced the generalized method of moments (GMM) and suggested it more effectively addresses endogeneity issues. The

dynamic system generalized method of moments (GMM) estimation is a statistical technique used in econometrics to estimate parameters in dynamic panel data models that involve lagged

dependent variables. It addresses issues of unobserved individual-specific effects and endogeneity by transforming the model, typically through first differencing, and using lagged levels of

the variables as instruments (Blundell and Bond, 1998). The method constructs moment conditions based on these instruments and minimizes a GMM objective function to obtain parameter

estimates. It is widely used for analyzing time series data in economics, such as economic growth and firm performance, due to its ability to handle dynamic structures and endogeneity

effectively (Blundell and Bond, 1998). Le et al. (2023) suggest that dynamic GMM better estimates panel data with many observations and short periods. If there are endogeneity issues, the

study applies the dynamic system generalized method of moments (GMM) to address endogeneity by using lagged values of variables as instruments (Nguyen and Su, 2022). In applying dynamic GMM

estimation, we follow the basic procedure of Anderson and Hsiao (1982) and Arellano and Bond (1991) by using lagged endogenous variables (FDI, TFP, GCF, INF) as GMM instruments. In addition,

Duong et al. (2023) note that it is easy for cross-sectional data to occur in a dataset that is too large and easily causes the asymptotic standard error of the dynamic GMM estimate.

Therefore, this study follows Le et al. (2023) and Duong et al. (2023) to implement dynamic GMM estimation with cross-section fixed effects. EMPIRICAL RESULTS DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS Table 1

presents descriptive statistics for all variables. The average economic growth rate of 90 middle-income countries is 4.05%, which is relatively low due to the absence of capital and human

resources in production. The mean of FDI is 3.8%, with a standard deviation of 6.43. This low mean value leads to unstable economic growth in middle-income countries (Nistor, 2014). However,

middle-income countries have good capital and human resource efficiency due to an average TFP of 1.12. Average AGRI is 14.65; gross capital formation is 25.45; GOV is 15.65; IMP is 45.17;

and average inflation is 31.2. PEARSON CORRELATION MATRIX Table 2 shows the correlation between variables with mixed positive and negative effects. As can be seen, all correlation

coefficients are <0.55. The highest correlation coefficient between GOV and IMP is about 0.545, showing a relatively strong positivity. Therefore, to check if our data sample has

multicollinearity, we use VIF to test the strength of the correlation matrix. Table 2 reports that the maximum value of VIF is 1.59, with a mean of 1.2. Therefore, our data sample does not

have multicollinearity issues because the VIFs of all variables are less than five (Duong et al., 2023; Le et al., 2023). REGRESSION MODELS AND RESULTS Table 3 reports the determinants of

the economic growth rates of middle-income countries. After using required tests such as the Hausman test (Shao et al., 2021), Redundant test, and Breusch–Pagan test for each model, the

results indicate that the random effects model is suitable for model 1 (because the _P_-value of the redundant test is <5% and the _P_-value of Hausman test is >5%) (Tiwari and

Mutascu, 2011) and fixed effects model is suitable for the remaining models (because the _P_-value of the redundant test and the _P_-value of the Hausman test are both <5%) (Habib et al.,

2019). However, the Wald test results suggest that the random effects model and fixed effects model estimations violate the heteroscedasticity, which may cause estimation bias. In addition,

we follow Duong et al. (2023) to perform the endogeneity test because the results will not be correct if the model is endogenous. First, the test model for the endogeneity of FDI is as

follows: $$\begin{array}{c} {Model}\,5:{FD{I}}_{i,t}=\alpha +{\beta }_{1}{TF{P}}_{it}+{\beta }_{2}{AGR{I}}_{it}+{\beta }_{3}{GC{F}}_{it}\\ \,+\,{\beta }_{4}{GO{V}}_{it}+{\beta

}_{5}{IM{P}}_{it}+{\beta }_{6}{IN{F}}_{it}{\alpha }_{i}+{\alpha }_{t}+{\varepsilon }_{i,t}\end{array}$$ (5) Second, the FDI acquired from the first period will be added as a variable in

Model 3. If the coefficient is a statistically significant variable, then there is a problem of endogeneity. Table 4 shows that AGRI, GOV, and IMP are variables without endogeneity problems

because the residual coefficients of these variables are not statistically significant in research. The remaining variables are all endogenous because the residual is statistically

significant. Therefore, we follow Duong et al. (2023) and Le et al. (2023) to re-estimate the results by employing the dynamic system GMM with cross-section fixed effects to overcome

heteroskedasticity and endogeneity. The estimation results using the GMM system method are presented in Table 5. The AR test determines whether there is a correlation in the model’s

residuals. The AR (2) test shows that the _P_ value is more than 5%, indicating no quadratic autocorrelation in the models. The AR (1) test is statistically significant, so the instrumental

variable is appropriate. In addition, the Hansen J-test results show that all models do not have overidentifications. ROBUSTNESS TESTS ROBUSTNESS TEST BY EMPLOYING ALTERNATIVE ECONOMIC

GROWTH PROXIES This section looks at the sustainability of our main results using different economic growth proxies. We computed the natural logarithm of GNP by following Omay et al. (2017).

We also computed the natural logarithm of GDP per capita by following Aslam et al. (2021). Table 6 presents the findings. ROBUSTNESS TEST BEFORE AND AFTER THE RECENT FINANCIAL CRISIS This

section examines the robustness of our findings before and after the financial crisis. In order to determine whether the fiscal crisis has an impact on our primary results, we follow

Himounet (2022) to split the sample into two time periods, such as before the financial crisis (from 1990 to 2007) and after the financial crisis (from 2008 to 2020). The robustness test

results were also estimated using the GMM approach. Table 7 presents the findings. DISCUSSIONS Table 5 shows that FDI has a positive relationship with economic growth. Specifically, FDI

increased by 1%, and the economic growth rate increased by 9.3%. Because FDI expands the market, it helps to increase capital, which leads to expanding production scale and increasing access

to more advanced technologies for local businesses. In addition, FDI also increases the efficiency of capital use, helping to increase export output and create a large budget to promote

economic growth. Our findings are consistent with Sokang (2018) and Agrawal and Khan (2011). However, our findings are inconsistent with Sabir et al. (2019) and Almfraji and Almsafir (2014)

because these studies have data sets collected from low-income, low-middle-income, upper-middle-income, and high-income countries from 1996 to 2016. Therefore, different sampling periods and

sample sizes may cause differences between our studies and those of Sabir et al. (2019) and Almfraji and Almsafir (2014). Our findings support economic growth theories because FDI increases

export activity, promoting the transfer of goods and services and increasing GDP. However, our findings do not support labor market dynamics theories because foreign investment projects

replace local workers with foreign workers. Technology transfer and skills development can lead to changes in local labor markets, causing adverse effects on economic growth. The findings

support hypothesis 1. In addition, the results of the above study show that TFP positively impacts economic growth. The results show that when the TFP increases by 1 point, the economic

growth rate increases by 16.38 percentage points. Improving workers’ qualifications, training, and transferring technology, as well as increasing the efficiency of capital use, helps

increase the TFP or demand for goods and services, leading to increased activities. Production is the basis for optimizing human resources and improving production processes to help improve

productivity, thereby promoting the country’s economic growth. Our findings agree with Saleem et al. (2019) and Bal and Rath (2014). However, our findings are inconsistent with those of Chen

and Xie (2015) because they analyzed data from 27 provinces in China from 1980 to 2010. The study used a slacks-based measure (SBM) model, leading to different results from our study. Our

findings also support economic growth and industrialization theories because TFP helps stabilize production activities thanks to technological and production process improvements due to

industrialization, creating favorable economic growth conditions. Our findings support the hypothesis 2. Besides, the interaction between FDI and TFP positively affects economic growth,

showing that foreign direct investment promotes total factor productivity. The results show that the interaction between FDI and TFP increases by 1%, and economic growth increases by 16.8%.

Because FDI increases technology transfer between countries and contributes to the training and development of human resources in the receiving countries, improving labor standards improves

human resources’ quality, increasing productivity and efficiency in production. Not only that, FDI is often accompanied by investment in infrastructure to help improve production processes

and expand consumption markets, creating a driving force for production growth. Our findings are consistent with those of Ahmed (2012) and Baltabaev (2014). However, our findings are not

consistent with Wang et al. (2021) because they analyze a sample from 21 OECD countries from 1996 to 2017. The study uses the panel and threshold regression models, so the findings differ

from those of our study. Additionally, our findings support the hypothesis 3. Table 5 indicates a positive coefficient between AGRI and economic growth in 90 middle-income countries.

Agriculture is a food source, creates more jobs, contributes to production and economic development in rural areas, and helps sustainable economic growth. Our findings are consistent with

those of Awokuse and Xie (2015). In addition, it also shows the positive impact of GCF on GDP because a percentage increase in GFC empowers GDP by 24.1%. Investing in fixed assets improves

infrastructure to help improve labor productivity and increase production capacity, promoting economic growth. Our results are consistent with those of Pasara and Garidzirai (2020), who

report a positive relationship between GCF and economic growth. However, this finding is inconsistent with Sinha and Kalayakgosi (2018), as they argue that disparities in investment quality

and high borrowing costs lead to an inability to access capital to support economic growth. We find that higher government spending reduces economic growth in middle-income countries.

Inefficient government spending causes waste, loss of resources, increases in debt, and negatively affects economic growth. Our finding is consistent with Nyasha and Odhiambo (2019), who

show a negative relationship between government spending and GDP. However, this finding is inconsistent with Nurudeen and Usman (2010) as they argue that government spending can stimulate

the economy, and human resource education and training promote economic growth. Table 5 shows the negative impact of imports on economic growth. Imports will reduce domestic production and

increase foreign debt. In addition, imports can increase competition with domestic economic sectors, causing negative impacts on economic growth. Our results align with Ahmed et al. (2013)

and Millia et al. (2021). Similarly, the inflation rate also has a negative relationship with GDP. A higher inflation rate reduces the value of money and increases the production costs.

Therefore, a higher inflation rate reduces competitiveness and discourages economic growth. Our findings are consistent with those of Ayyoub et al. (2011) and Mwakanemela (2013). For the

first robustness test, we employ alternative economic growth proxies. According to Table 6, FDI significantly impacts GDP (GNP) and GDP per capita, which aligns with our main findings. Our

finding is consistent with Sokang (2018) and Agrawal and Khan (2011). The results demonstrate a positive correlation between TFP, GDP per capita, and LN(GNP). Our results agree with Saleem

et al. (2019) and Bal and Rath (2014). Table 6 also reports that the interaction between FDI and TFP positively affects GDP and GDP per capita. However, Table 6 reports that the interaction

between FDI and TFP negatively correlates with LN(GNP), which is inconsistent with our main findings. Some FDI enterprises are unwilling to cooperate with domestic enterprises, so it is

challenging to train human resources and transfer new technologies, causing dependence on imported goods and not promoting production activities, thereby reducing the contribution of

enterprises to GNP (Malovic et al., 2019). In the second robustness test, we examine whether the main findings are robust before and after the recent financial crisis. Table 7 shows a

positive relationship between FDI and GDP after the financial crisis, consistent with our main finding. This result is consistent with Sokang (2018), Saleem et al. (2019), and Bal and Rath

(2014). However, before the financial crisis, the results showed that FDI harmed economic growth. FDI firms mainly focused on a few key industries and sectors, leading to a lack of diversity

and reduced competition and economic growth before the financial crisis. The results also show that TFP positively impacts economic growth before and after the fiscal crisis. Table 7 also

reports that the interaction between FDI and TFP is positively related to economic growth before the financial crisis, which is consistent with our result. However, we also find a negative

correlation coefficient between the interaction of FDI and TFP on GDP after the financial crisis. This result is consistent with Wang et al. (2021) because the financial crisis forced

national governments to propose production activities due to low demand or too much inventory, leading to stagnant production. In some cases, concentrated FDI focusing on specific industries

or economic sectors can weaken the diversity and competition of other industries, leading to the development of non-commercial or non-manufacturing industries and reduced GDP growth. In

addition, the economy was significantly weakened after the financial crisis, making management ineffective and unprofessional in transferring new technology to FDI projects; work for

interactions between FDI and TFP reduces economic growth after the financial crisis. CONCLUSION This study extends prior literature by examining how the interaction between FDI and TFP

affects economic growth in 90 middle-income countries. Our data sample is an unbalanced panel with 2714 observations from 90 middle-income countries from 1990 to 2020. We use the Generalized

Method of Moments to overcome heteroscedasticity and endogeneity issues. The findings report a positive relationship between FDI and economic growth in the middle-income countries. While

this result supports the economic growth and industrialization theories, it does not align with labor market dynamics theories. Secondly, TFP positively affects GDP, and this finding

supports economic growth and industrialization theories. Finally, the interaction of FDI and TFP positively impacts economic growth. In addition, the main findings are also robust even

though we employ alternative economic growth proxies. Furthermore, the impact of FDI and TFP on economic growth has been sustainable since the fiscal crisis. However, the impact of the

interaction between FDI and TFP on economic growth was only robust before the financial crisis. LIMITATION AND IMPLICATION This research brings practical implications for policymakers to

promote stable and transparent economic policies to create confidence for foreign investors and offer attractive preferential policies for FDI. For example, policies that encourage training

and human resource development because providing highly qualified and skilled labor increases a country’s competitiveness and attracts foreign businesses. Additionally, it encourages

technology transfer from foreign investors to domestic industries. This proposal can enhance local capacity and contribute to technological progress. Invest in infrastructure development to

enhance connectivity and create a favorable business environment. Reliable infrastructure is attractive to foreign investors. Establish or strengthen an Investment Promotion Agency (IPA) to

attract foreign investors. These agencies can provide information, simplify processes, and offer incentives to encourage FDI. Besides, it is necessary to open international free trade

combined with investing in tax reduction policies, improving infrastructure, improving labor quality, and reducing cumbersome transaction procedures to help investors want to invest and

expand production or business scale locally. Reducing the tax burden and diversifying tax incentives have created a favorable investment environment to attract FDI capital. On the other

hand, policymakers should also provide incentives to increase productivity as it plays an important role in developing the local economy. It is necessary to promote the application of new

technology in industries. Encourage businesses to apply digitalization and automation to increase efficiency. Support startups and small businesses. Innovation often comes from smaller, more

agile businesses and can positively impact TFP (Chi et al., 2021). Additionally, investment in education and skills development programs is needed to improve human capital. A highly skilled

workforce will be more productive and adapt to technological changes that increase skills, productivity, and creativity. It is necessary to apply advanced management methods like those in

developed countries, enhance coordination and interaction between departments in the organization, and create an effective and motivating working environment, such as productivity management

tools such as lean management methods. Besides in-depth and breadth, it is necessary to create a breakthrough in TFP for other industries such as processing, manufacturing, and services. In

terms of depth, we should go deeper into the value chain in the field of heavy industry, such as assembly, processing, and developing many service industries with high added value, such as

IT software products and digital finance. In terms of breadth, many large-scale industries and important contributions to economic growth should be selected to focus on improving

productivity, quality, and added value, such as light industries such as textiles, garments, and garments food industry and focus on restructuring from the production of low-value-added

goods to high-value-added goods. In addition, it is necessary to develop appropriate policies to synchronize FDI and TFP. For example, governments can encourage foreign investment in

technological research and development (R&D) to encourage innovation, increase foreign direct investment, and increase total factor productivity (Ullah et al., 2023). Furthermore, this

study shows that policymakers provide financial support programs or subsidies to attract foreign investment to encourage competition and entrepreneurship, helping to grow the economy.

Although this study extends the growing literature on sustainable development goals, it has the following limitations. First, GMM cannot distinguish the short- and long-term economic

effects, so it is limited compared to Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL). Second, our study was limited to 90 middle-income countries based on the 2010 World Bank classification. Future

studies compare the results in low- and high-income countries. Furthermore, future studies may consider short-term and long-term financial and economic effects using the ARDL method. DATA

AVAILABILITY The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GTQOTC. REFERENCES *

Adewole AO (2012) Effect of population on economic development in Nigeria: a quantitative assessment. Int J Phys Soc Sci 2(5):1–14 Google Scholar * Agrawal G, Khan MA (2011) Impact of FDI

on GDP: a comparative study of China and India. Int J Bus Manag 6(10):71–79. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v6n10p71 Article Google Scholar * Ahmed EM (2012) Are the FDI inflow spillover

effects on Malaysia’s economic growth input driven? Econ Model 29(4):1498–1504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.04.010 Article Google Scholar * Ahmed SK, Hoque MA, Jobaer SM (2013)

Effects of export and import on GDP of Bangladesh an empirical analysis. Int J Manag 2(3):28–37 Google Scholar * Almfraji MA, Almsafir MK (2014) Foreign direct investment and economic

growth literature review from 1994 to 2012. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci 129:206–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.668 Article Google Scholar * Anderson TW, Hsiao C (1982)

Formulation and estimation of dynamic models using panel data. J Econom 18(1):47–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(82)90095-1 Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Arazmuradov A,

Martini G, Scotti D (2014) Determinants of total factor productivity in former Soviet Union economies: a stochastic frontier approach. Econ Syst 38(1):115–135.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2013.07.007 Article Google Scholar * Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to

employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297968 Article Google Scholar * Arslan F (2016) Social physics: how good ideas spread—the lessons from a new

science. Alex Pentland, New York, NY; The Penguin Press, 2014, 300 pp * Aslam B, Hu J, Shahab S, Ahmad A, Saleem M, Shah SSA, Hassan M (2021) The nexus of industrialization, GDP per capita

and CO2 emission in China. Environ Technol Innov 23:101674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2021.101674 Article CAS Google Scholar * Awokuse TO, Xie R (2015) Does agriculture really matter

for economic growth in developing countries. Can J Agric Econ/Rev Can Agroecon 63(1):77–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/cjag.12038 Article Google Scholar * Ayyoub M, Chaudhry IS, Farooq F

(2011) Does inflation affect economic growth? The case of Pakistan. Pakistan J Soc Sci 31(1):51–64 Google Scholar * Bal DP, Rath BN (2014) Public debt and economic growth in India: a

reassessment. Econ Anal Policy 44(3):292–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2014.05.007 Article Google Scholar * Balsa-Barreiro J, Li Y, Morales A (2019) Globalization and the shifting

centers of gravity of world’s human dynamics: implications for sustainability. J Clean Prod 239:117923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117923 Article Google Scholar *

Balsa-Barreiro J, Menendez M, Morales AJ (2022) Scale, context, and heterogeneity: the complexity of the social space. Sci Rep 12(1):9037. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12871-5 Article

ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Balsa-Barreiro J, Wang S, Tu J, Li Y, Menendez M (2023) The nexus between innovation and environmental sustainability. Front Environ Sci

11:1194703. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1194703 Article Google Scholar * Baltabaev B (2014) Foreign direct investment and total factor productivity growth: new macro‐evidence.

World Econ 37(2):311–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12115 Article Google Scholar * Berrebi C, Ostwald J (2016) Terrorism and the labor force: evidence of an effect on female labor force

participation and the labor gender gap. J Confl Resolution 60(1):32–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002714535251 Article Google Scholar * Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and

moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87(1):115–143 Article Google Scholar * Chi M, Muhammad S, Khan Z, Ali S, Li RYM (2021) Is centralization killing innovation? The

success story of technological innovation in fiscally decentralized countries. Technol Forecast Soc Change 168:120731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120731 Article Google Scholar

* Chen S, Xie Z (2015) Is China’s e-governance sustainable? Testing Solow IT productivity paradox in China’s context. Technol Forecast Soc Change 96:51–61.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2014.10.014 Article Google Scholar * Decreuse B, Maarek P (2015) FDI and the labor share in developing countries: a theory and some evidence. Ann Econ

Stat/Ann Écon Stat (119–120):289–319. https://doi.org/10.15609/annaeconstat2009.119-120.289 * Dettori B, Marrocu E, Paci R (2012) Total factor productivity, intangible assets and spatial

dependence in the European regions. Reg Stud 46(10):1401–1416. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2010.529288 Article Google Scholar * Duong KD, Le Vu H, Nguyen DV, Pham H (2023) How do

employee stock ownership plans programs and ownership structure affect bank performance? Evidence from Vietnam. Manag Decision Econ 44(5):2604–2614. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3836 Article

Google Scholar * Duong KD, Nguyen SD, Phan PTT, Luong LK (2022) How foreign direct investment, trade openness, and productivity affect economic growth: evidence from 90 middle-income

countries. Sci Pap Univ Pardubic Ser D Fac Econ Adm 30(3):1615. https://doi.org/10.46585/sp30031615 Article Google Scholar * Fleisher B, Li H, Zhao MQ (2010) Human capital, economic

growth, and regional inequality in China. J Dev Econ 92(2):215–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2009.01.010 Article Google Scholar * Habib M, Abbas J, Noman R (2019) Are human

capital, intellectual property rights, and research and development expenditures really important for total factor productivity? An empirical analysis. Int J Soc Econ 46(6):756–774.

https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-09-2018-0472 Article Google Scholar * Himounet N (2022) Searching the nature of uncertainty: macroeconomic and financial risks VS geopolitical and pandemic

risks. Int Econ 170:1–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2022.02.010 Article Google Scholar * Le ANN, Pham H, Pham DTN, Duong KD (2023) Political stability and foreign direct investment

inflows in 25 Asia-Pacific countries: the moderating role of trade openness. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02075-1 Article Google Scholar * Lewis WA

(2013) Theory of economic growth. Routledge * Malovic M, Özer M, Zdravkovic A (2019) Misunderstanding of FDI in the Western Balkans: cart before the horse and wheels without suspension. J

Balkan Near East Stud 21(4):462–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2018.1506285 Article Google Scholar * Megbowon E, Mlambo C, Adekunle B (2019) Impact of China’s outward FDI on

sub-saharan africa’s industrialization: evidence from 26 countries. Cogent Econ Financ 7(1):1681054. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2019.1681054 Article Google Scholar * Miao L, Zhuo Y,

Wang H, Lyu B (2022) Non-financial enterprise financialization, product market competition, and total factor productivity of enterprises. Sage Open 12(2):21582440221089956.

https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221089956 Article Google Scholar * Millia H, Syarif M, Adam P, Rahim M, Gamsir G, Rostin R (2021) The effect of export and import on economic growth in

Indonesia. Int J Econ Financ Issues 11(6):17–23. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijefi.11870 Article Google Scholar * Moghaddasi R, Pour AA (2016) Energy consumption and total factor productivity

growth in Iranian agriculture. Energy Rep 2:218–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2016.08.004 Article Google Scholar * Mwakanemela K (2013) Impact of inflation on economic growth: a

case study of Tanzania. Asian J Empir Res 3(4):363–380 Google Scholar * Nguyen CP, Su TD (2022) Export dynamics and income inequality: new evidence on export quality. Soc Indic Res

163(3):1063–1113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02935-4 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nistor P (2014) FDI and economic growth, the case of Romania. Procedia Econ

Finance 15:577–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00514-0 Article Google Scholar * Nursamsu S, Hastiadi FF (2015) Analysis of international R&D spillover from international

trade and foreign direct investment channel: evidence from Asian newly industrialized countries. J Econ Coop Dev 36(2):125–154 Google Scholar * Nurudeen A, Usman A (2010) Government

expenditure and economic growth in Nigeria, 1970–2008: a disaggregated analysis. Bus Econ J 4(1):1–11 Google Scholar * Nyasha S, Odhiambo NM (2019) The impact of public expenditure on

economic growth: a review of international literature. Folia Oecon Stetin 19(2):81–101. https://doi.org/10.2478/foli-2019-0015 Article Google Scholar * Omay T, Gupta R, Bonaccolto G (2017)

The US real GNP is trend-stationary after all. Appl Econ Lett 24(8):510–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2016.1205719 Article Google Scholar * Omri A, Kahouli B (2014) Causal

relationships between energy consumption, foreign direct investment and economic growth: fresh evidence from dynamic simultaneous-equations models. Energy Policy 67:913–922.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.11.067 Article Google Scholar * Pasara MT, Garidzirai R (2020) Causality effects among gross capital formation, unemployment and economic growth in

South Africa. Economies 8(2):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8020026 Article Google Scholar * Rai SM, Brown BD, Ruwanpura KN (2019) SDG 8: Decent work and economic growth—a gendered

analysis. World Dev 113:368–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.09.006 Article Google Scholar * Sabir S, Rafique A, Abbas K (2019) Institutions and FDI: evidence from developed

and developing countries. Financ Innov 5(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-019-0123-7 Article Google Scholar * Saleem H, Shahzad M, Khan MB, Khilji BA (2019) Innovation, total factor

productivity and economic growth in Pakistan: a policy perspective. J Econ Struct 8(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-019-0134-6 Article Google Scholar * Shao XF, Li Y, Suseno Y, Li

RYM, Gouliamos K, Yue XG, Luo Y (2021) How does facial recognition as an urban safety technology affect firm performance? The moderating role of the home country’s government subsidies. Saf

Sci 143:105434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105434 Article Google Scholar * Sinha N, Kalayakgosi KA (2018) Government size and economic growth in Botswana: an application of

non-linear Armey curve analysis. VISION 5(1):60–90. https://doi.org/10.17492/vision.v5i1.13274 Article Google Scholar * Sokang K (2018) The impact of foreign direct investment on the

economic growth in Cambodia: empirical evidence. Int J Innov Econ Dev 4(5):31–38. https://doi.org/10.18775/IJIED.1849-7551-7020.2015.45.2003 Article ADS Google Scholar * Tiwari AK,

Mutascu M (2011) Economic growth and FDI in Asia: a panel-data approach. Econ Anal Policy 41(2):173–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0313-5926(11)50018-9 Article Google Scholar * Tran VH, Lu

NP, Le NTP, Duong KD (2023) How do foreign direct investment and economic growth affect environmental degradation? Evidence from 47 middle-income countries. Sci Pap Univ Pardubic Ser D Fac

Econ Adm 31(1):1671. https://doi.org/10.46585/sp31011671 Article Google Scholar * Ullah S, Ahmad T, Lyu B, Sami A, Kukreti M, Yvaz A (2023) Integrating external stakeholders for

improvement in green innovation performance: role of green knowledge integration capability and regulatory pressure. Int J Innov Sci. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-12-2022-0237 * Wang M, Pang

S, Hmani I, Hmani I, Li C, He Z (2021) Towards sustainable development: How does technological innovation drive the increase in green total factor productivity? Sustain Dev 29(1):217–227.

https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2142 Article Google Scholar * Wannakrairoj W, Velu C (2021) Productivity growth and business model innovation. Econ Lett 199:109679.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2020.109679 Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Zhan, X, Li, RYM, Liu, X, He, F, Wang, M, Qin, Y, … & Liao, W (2022) Fiscal decentralisation and

green total factor productivity in China: SBM-GML and IV model approaches. Front Environ Sci 1701. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.989194 Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study

is supported by Ton Duc Thang University, Van Lang University and Ho Chi Minh City Open University. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public,

commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Faculty of Accounting and Auditing, Van Lang University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Hoa Thanh Phan Le *

Faculty of Finance and Banking, Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Ha Pham * Faculty of Finance and Banking, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Nga

Thi Thu Do & Khoa Dang Duong Authors * Hoa Thanh Phan Le View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ha Pham View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Nga Thi Thu Do View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Khoa Dang Duong View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS HTPL ([email protected]) analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the first draft of the

manuscript. HP ([email protected]) and NTTD ([email protected]) performed the experiments, contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools, or data. KDD ([email protected])

conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Khoa

Dang Duong. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICAL APPROVAL Ethical approval is not applicable because this article does not contain any

studies with human or animal subjects. INFORMED CONSENT Informed consent is not applicable because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects. ADDITIONAL

INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION APPENDICE RIGHTS

AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in

any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The

images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not

included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly

from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Le, H.T.P., Pham,

H., Do, N.T.T. _et al._ Foreign direct investment, total factor productivity, and economic growth: evidence in middle-income countries. _Humanit Soc Sci Commun_ 11, 1388 (2024).

https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03462-y Download citation * Received: 30 August 2023 * Accepted: 10 July 2024 * Published: 19 October 2024 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03462-y SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative