- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACTS In Nigeria, there is a growing concern that graduates from science and engineering fields are not ready for entrepreneurship due to low business creation among young individuals.

Another perspective suggests that entrepreneurship curriculum only prepares the students to seek for employment rather than become entrepreneurs. Previous studies have revealed that there

are several cognitive factors responsible for readiness to start a business other than entrepreneurship education. The purpose of this study is to determine social cognitive factors that can

stimulate start-up readiness. Thus, this study examined the mediating effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up

readiness. Three dimensions of entrepreneurship education and four dimensions of ESE were examined as determinants of start-up readiness using survey research approach. Data from 289

exit-level students from three Technical Vocational Education and Technology (TVET) colleges were analysed using SPSS 25 and Smart PLS 4 software. Entrepreneurship education (in terms of

technical skills and business management skills) shows partial support for ESE (in terms of searching, planning, and implementing). However, entrepreneurship education (in terms of personal

skills) only shows support for ESE (in terms of marshalling). The results of the mediation analysis suggest that ESE (in terms of searching, planning, and implementing) partially mediates

the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness, while ESE marshalling failed to mediate the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up

readiness. This study also revealed that apart from ESE marshalling, all components of ESE have a direct and significant relationship with start-up readiness. Another contribution of this

study indicates that personal entrepreneurial skills are required antecedent for enhancing business resources gathering skills towards start-up readiness among young individuals in Nigeria.

The study suggests fostering entrepreneurial mindset via simulation-based techniques, role playing, and mentoring with practical translations. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS

EXTRA-CURRICULAR SUPPORT FOR ENTREPRENEURSHIP AMONG ENGINEERING STUDENTS: DEVELOPMENT OF ENTREPRENEURIAL SELF-EFFICACY AND INTENTIONS Article Open access 11 October 2023 DESIGNING A

FRAMEWORK FOR ENTREPRENEURSHIP EDUCATION IN CHINESE HIGHER EDUCATION: A THEORETICAL EXPLORATION AND EMPIRICAL CASE STUDY Article Open access 16 April 2024 INDIVIDUAL ENTREPRENEURIAL

ORIENTATION FOR ENTREPRENEURIAL READINESS Article Open access 13 February 2024 INTRODUCTION Globally, entrepreneurial activity has become a dominant phenomenon that contributes to the

increase in the rate of employment and socio-economic development (Boubker et al., 2021; Cassol et al., 2022). This is evident in the recent transformation and growth in the banking,

telecommunications, and retail industries in Africa (Herrington and Coduras, 2019). Many countries in the Sub-Saharan African region, including Nigeria are gradually turning their attention

from raw material mineral extraction to technology innovation (McKinsey Global Institute Analysis, 2017). However, a recent report suggests that Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest shortage

of employment opportunities, with Europe 71%, North America 64%, Asia 62%, Latin America 79%, North Africa 70%, and Sub-Saharan Africa 88% (ILO, 2018). Africa is projected to be home to the

youngest and largest population by 2050, but 60% of its population lives in poverty (McKinsey Global Institute, 2022). Scholarships in entrepreneurship increasingly argue that

entrepreneurship offers the pathway out of poverty (Chigunta, 2017; Dvouletý and Orel, 2019). In the light of this, young individuals can no longer rely on the private sector and government

to create jobs. There is a sense of respect for people who start their own business to become self-employed, and possibly, provide employment for others. Despite being the largest economy in

Africa, Nigeria is ranked among countries with high poverty rate (40.1%) in Africa (World Population Review, 2023). As of 2022, 53.4% of young people are without jobs (National Bureau of

Statistics, 2023), making it the second country with the highest unemployed youth in Africa after South Africa at 66.5% (Statistic South Africa, 2022). In Nigeria, there is a growing concern

that graduates, especially from science and engineering fields are not ready for entrepreneurship due to low business creation among the youth (Edokpolor and Owenvbiugie, 2017). Another

perspective suggests that the entrepreneurship education curriculum only prepares the students to seek for employment rather than become entrepreneurs (Jegede and Nieuwenhuizen, 2020).

Previous studies have revealed that there are several cognitive factors responsible for readiness to start a business other than entrepreneurship education (Fayolle and Gailly, 2015;

Potishuk and Kratzer, 2017). Besides, some individuals may not act if certain personality traits are not triggered (Adeniyi, 2021). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) has been described as

a precursor for entrepreneurial action. The purpose of this study is to determine the mediation effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the relationship between entrepreneurship education

and start-up readiness among young individuals in Nigeria. To achieve this purpose, the following research objectives were stated: * To examine the effects of entrepreneurship education on

entrepreneurial self-efficacy * To determine the mediating effects of ESE in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness. * To measure the influence of ESE on

start-up readiness. This study is one of the first efforts to validate the relationships between dimensions of entrepreneurship education and dimensions of entrepreneurial self-efficacy for

start-up readiness in a developing context, specifically in Africa. HIGHLIGHTS * The findings revealed that entrepreneurship education shows a partial relationship with ESE. * ESE partially

mediates the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness. * Personal entrepreneurial skills are essential antecedents that can enhance the ability to gather

economic resources for business start-ups. * Another contribution of this study indicates that there is need for universities and entrepreneurship professionals to improve the level of

social cognitive value (personal entrepreneurial traits) via relevant entrepreneurship training with practical translation. LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES FORMULATION In this study,

self-efficacy was conceptualised from the social cognitive theory to create a synthesis with previous application of self-efficacy to entrepreneurship in order to understand the construct of

ESE. The relationship between entrepreneurship education and ESE was extensively unpacked from previous studies to identify gaps in literature. This study aims to determine factors that can

stimulate start-up readiness among young individuals in Nigeria. SELF-EFFICACY Self-efficacy is a multidisciplinary phenomenon, and multidimensional in nature, and therefore holds no

consistent definition (Drnovšek et al., 2010). For example, the social cognitive theorists conceptualise self-efficacy as individuals’ belief in their ability to perform a task that

influences attitudes and behaviours (Bandura, 1994; Lent and Maddux, 1997). Psychologists hold the assumption that self-efficacy is the estimation of one’s capabilities to implement a

specific behaviour to achieve a desired outcome (Bieschke, 2006). The psychologists maintain that all psychological processes and behavioural functions are determined by the alteration of an

individual’s sense of mastery known as self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986; Maddux, 2013). Scholars in this school of thought also emphasise the need to define self-efficacy not only as a

personality trait, but within the context of relatively specific behaviour in specific contexts (Bandura, 1986; Maddux, 2013). For this reason, economists examine the achievement of set

economic goals by an individual in relation to perceived self-efficacy. Scholarships in this field view self-efficacy as individuals’ domain-specific capabilities that control internal

constraints in order to propel economic behaviour (Wuepper and Lybbert, 2017). The economists argue that sufficient self-efficacy is required to create investment and set more ambitious

goals, which is a promising avenue out of poverty (Wuepper and Lybbert, 2017). This assumption is evident in the empirical finding that increased self-efficacy is associated with

opportunity-driven entrepreneurship (Tyszka et al., 2011), which is referred to as economic self-efficacy (Grabowski et al., 2001). Social psychologists refer to self-efficacy as an

individual’s personal belief in his or her capacity to accomplish a specific action or behaviour (Grabowski et al., 2001). Researchers in this domain approach self-efficacy as a sense of

competence and potency to navigate social situations (Rudy et al., 2012). Social psychologists explored the social aspect of self-efficacy as individuals’ confidence in their ability to

perform social interactional tasks required to activate and maintain interpersonal relationships (Smith and Betz, 2000). In this context, it is considered as social self-efficacy, which is a

useful tool to shape career decisions through the management of social engagements (Smith and Betz, 2000, Rudy et al., 2012). Entrepreneurship scholars attempt to define self-efficacy from

two perspectives of task-specific ability (Boyd and Vosikis, 1994; De Noble et al., 1999), and performance of action or outcome (Segal et al., 2002). For instance, proponents in the former

refer to self-efficacy as the belief in ones’ ability to successfully launch a business start-up (Boyd and Vozikis, 1994, Wilson et al., 2007), while the latter view self-efficacy as

individuals’ perception about their capabilities to organise and implement entrepreneurial behaviour required to achieve a given outcome (Segal et al., 2002). It is referred to as

entrepreneurial self-efficacy when viewed as a key construct to starting a new business (Chen et al., 1998). However, a unification approach was proposed by Drnovšek et al. (2010) by

incorporating the task specificity and environmental factors of ESE. The scholars stated that ESE is a multidimensional construct made up of goal and control beliefs, and propositions as it

shapes the process of starting a business, and the effects of these beliefs on task performance and outcome attainment (Drnovšek et al., 2010). ESE is domain-specific which is fundamental to

its multidimensional attributes. This study draws on the abovementioned theoretical clarifications to underscore the mediating effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the relationship

between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness. ESE CONSTRUCT It has been argued that ESE is best viewed as a multidimensional construct which focuses on goal and control

perceptions, and propositions to comprehend how these dimensions will impact the process of developing a new start-up (Drnovšek et al., 2010). A considerable number of studies have been

conducted on the various dimensions of ESE (Chen et al., 1998; Pihie and Bagheri, 2013; Setiawan, 2014). Each study identified a different pattern of ESE structure. In demonstrating the

differing level of ESE between managers and entrepreneurs, Chen et al. (1998) applied five underlying dimensions of ESE construct but utilised a total ESE score to distinguish managers from

entrepreneurs. The scholars offered little understanding on the most specific component of ESE that can stimulate the creation of entrepreneurial intention. In a bid to assess university

students’ entrepreneurial intention, Pihie and Bagheri (2013) adopted five components of ESE to assign task and roles of an entrepreneur which are marketing, accounting, personnel

management, production management and organising. The authors successfully proved that ESE is the most significant and positive factor that can influence entrepreneurial intention, but

failed to provide the specific, or most significant determinant of entrepreneurial intention. Setiawan (2014) adapted De Noble et al.’s (1999) six dimensions of ESE which are developing new

product and market opportunities, building an innovative environment, initiating investor relationship, developing critical human resources, defining core purpose, and coping with unexpected

challenges. Using descriptive statistics, the author was able to rate and compare the students’ ESE dimensions (task ability) but did not statistically measure the impact on their start-up

development (outcome ability). Discourse on various dimensions of ESE is well documented in literature. Drnovšek et al. (2010) examine the relationship between entrepreneurial start-up

process and ESE components which are entrepreneurial intent, opportunity search, decision to exploit, and opportunity exploitation. The authors demonstrated that ESE is best adopted as a

multidimensional construct in measuring phases of entrepreneurial behaviour. Chen et al. (1998) adopted five sources of ESE dimension to differentiate managers from entrepreneurs; these are,

marketing skills, innovation skills, management skills, risk-taking, and financial control. De Noble et al. (1999) proposed six dimensions of ESE: risk and uncertainty management skills,

innovation and product development skills, interpersonal and networking management skills, opportunity recognition, procurement and allocation of critical resource, and development and

maintenance of an innovative environment. The authors show that these skill factors have significant association with entrepreneurial intention (De Noble et al., 1999). Barbosa et al. (2007)

assess cognitive style and risk preference on four task phases of ESE, which are opportunity ESE, managerial ESE, relationship ESE, and tolerance ESE. The study identified individuals’ ESE

variations in relation to risk-taking ability. Mueller and Goic (2003) investigated differences in business students ESE task phases in US and Croatia. While all pairs of ESE task phases

(searching, planning, and implementing) significantly impacted the students’ entrepreneurial orientation, ESE marshalling had low score among students from Croatia. ESE task phases of

searching, planning, marshalling, and implementing were originally conceptualised by Stevenson et al. (1985), and the scales were further refined by McGee et al. (2009). This study’s

analytical grid is generated from these four components of ESE (McGee et al., 2009; Adeniyi et al., 2022). Smith and Betz (2000) contend that the theory of self-efficacy can be adopted to

explain one’s career decision and behaviour and help to conceptualise interventions capable of strengthening efficacy perception within a specific career domain. Accordingly,

entrepreneurship education is drawn as a strengthening variable for ESE to impact start-up readiness among students of TVET colleges. ENTREPRENEURSHIP EDUCATION Entrepreneurship education

has been proven to be one of the mechanisms to create job opportunities, improve standard of living, sustainable economic growth and development, and increases individuals’ entrepreneurial

mindset (Chigunta, 2017; Herington and Coduras, 2019). Entrepreneurship education is essential for business start-ups and acquisition of knowledge (Young, 1997). Accordingly,

entrepreneurship education aims at enhancing entrepreneurial mindset, entrepreneurial attitudes and skills as well as dimensions of idea generation, start-ups, growth and innovation

(European Commission, 2012). Entrepreneurship education is a crucial predictor of personality traits for business creation (Hampel-Milagrosa, 2010). Business start-ups are a catalyst for

economic development as they help to reduce unemployment. Entrepreneurship education is one of the most relevant drivers of business start-ups. Previous study indicated that there is a large

shortage of managerial skills in SMEs (Jack and Anderson, 1999), and suggested the incorporation of specific skills set in entrepreneurship education (Martins and Pear, 2015; Almahry and

Sarea, 2018). In the light of this, Hisrich and Peter (1998), as cited by Henry et al. (2005), categorised three specific skills as determinants of business success required by

entrepreneurs, namely, technical skills, business management skills and personal entrepreneurial skills. In a similar vein, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

annual report in 2014 identified technical skills, business management skills and personal entrepreneurial skills as the required skills for young entrepreneurs (OECD, 2014). Extant studies

have advocated for the adoption of these specific entrepreneurial skills as content of entrepreneurship education towards business start-ups (Martins and Pear, 2015; Almahry and Sarea,

2018). In addition, Martins and Pear (2015) demonstrated the need for entrepreneurship education to interact with other personality traits for business success. This discussion informs the

introduction of ESE as the most consistent predictor of entrepreneurial success (Drnovšek et al., 2010). ENTREPRENEURSHIP EDUCATION AND ESE Scholarships in entrepreneurship have shown that

entrepreneurship can be learned through training (Wilson et al., 2007; Fayolle, 2018), and the required personality ability, and attitudes to become an entrepreneur can be impacted through

entrepreneurship education (Maritz and Brown, 2013). Entrepreneurship education has the potential to stimulate students’ ESE through the accomplishment of task-specific entrepreneurial

activities. Accordingly, prior studies reveal that entrepreneurship education and training can influence individuals’ ESE, attitude and behavioural intention towards business start-ups

(Piperopoulos and Dimov, 2015; Nowiński et al., 2019). Maritz and Brown (2013) contributed to the value of entrepreneurship education programme and entrepreneurial learning on individuals’

ESE by applying ESE measures to entrepreneurship education. Results indicated that participation in the entrepreneurship training programme had a positive significant impact on the ESE of

the participants. Piperopoulos and Dimov (2015) assessed entrepreneurial intention of students in relation to theoretical and practical entrepreneurship courses. The authors found that

higher ESE is associated with lower entrepreneurial intentions in theoretical-related courses, while higher entrepreneurial intentions are associated with practical related courses. This

supports the assumption that entrepreneurship is practice oriented. Using the entrepreneurship tool developed by Gedeon and Valliere (2018), Mozahem and Adlouni (2021) demonstrated that

students who have taken entrepreneurship courses show higher self-efficacy than students who are yet to take the courses. Ahmed et al. (2020) applied the components of theory of planned

behaviour and empirically proved that entrepreneurship training programme significantly influence perceived control (self-efficacy) of students. Nowiński et al. (2019) also proved that

entrepreneurship education positively affects ESE task-specific of searching for opportunities, business planning, resource marshalling, and financial skills. Therefore, the relationship

between entrepreneurship education components (technical skills, business management skills, personality skills) and ESE business searching, business planning, resource marshalling, and

business implementing is hypothesised as follows: HYPOTHESIS 1 H1a: EE in terms of (a) technical skill, (b) business management skill, (c) personality skill significantly contributes to ESE

business searching for start-up establishment. H1b: EE in terms of (a) technical skill, (b) business management skill, (c) personality skill significantly contributes to ESE business

planning for start-up establishment. H1c: EE in terms of (a) technical skill, (b) business management skill, (c) personality skill significantly contributes to ESE resource marshalling for

start-up establishment. H1d: EE in terms of (a) technical skill, (b) business management skill, (c) personality skill significantly contributes to ESE business implementing for start-up

establishment. MEDIATING ROLES OF ESE ESE has also been found to significantly mediate the relationship between intent to start a business and behaviours of individuals as influenced by

entrepreneurship education. The study conducted by Hien and Cho (2018) reveals that entrepreneurship based on self-efficacy shows significant mediating effects on innovative start-up

intentions of university students in Vietnam. Nowiński et al. (2019) examined the contribution of entrepreneurship education to entrepreneurial intention of university students from Czech

Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Poland. The results showed that entrepreneurship education had direct impact on the students’ entrepreneurial intention in Poland only, being the only one of

the four countries that established entrepreneurship education at high school level. Additionally, the authors found that ESE task related to searching, planning, marshalling and

implementing mediated the influence of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention. The study conducted in China by Wu et al. (2022) showed that ESE had complete mediating

effects between entrepreneurship education and college students’ entrepreneurial intention to start a business. In a similar vein, Hoang et al. (2021) investigated the mediating roles of

self-efficacy between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Vietnam. The authors argue that entrepreneurship education positively influences

entrepreneurial intention, and the relationship is strongly mediated by self-efficacy. Yeh et al. (2021) further elucidate the significant mediating effects of Internet ESE in the

relationship between entrepreneurial education and internet entrepreneurial performance. The study conducted by Prabhu et al. (2012) on proactive personality and entrepreneurial intent

reveal that ESE completely mediated the relationship between proactive personality, and two manifestations of entrepreneurial intention (lifestyle EI and high growth EI). In India, Kumar and

Shukla (2022) demonstrated that ESE fully mediated the relationship between creativity and entrepreneurial intention of management students. Likewise, Udayanan (2019) highlighted that the

influence of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intention was fully mediated by ESE. In African context, few empirical studies have been conducted to comprehend the importance of ESE in

strengthening entrepreneurial readiness for start-ups. The empirical study conducted in Ghana by Puni et al. (2018) indicated that ESE is a central cognitive mechanism that can transform

entrepreneurship education to start-up intention. The authors found that ESE significantly mediated the relationship between entrepreneurship education and students’ start-up intentions.

Oyugi’s (2015) study found that ESE partially mediated the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention among university students in Uganda. Scholars have

argued that theoretical entrepreneurship education in Africa may work differently in developed countries (Puni et al., 2018), and call for further investigation on the effects of ESE as a

determinant of start-ups readiness. Mc Gee et al. (2009) added that one of the challenges hindering the development and effective application of ESE construct is researchers’ over reliance

on data collected from university students. The application of ESE construct within the context of TVET institutions is under-researched (Pihie and Bagheri, 2011), especially in Africa

(Adeniyi et al., 2022). Based on the mediating effects of ESE in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and readiness to start a new business, the hypothesis is formulated thus:

HYPOTHESIS 2 H2a: ESE business searching significantly mediates the relationship between EE in terms of (a) technical skill, (b) business management skill, (c) personality skill and

start-up readiness. H2b: ESE business planning significantly mediates the relationship between EE in terms of (a) technical skill, (b) business management skill, (c) personality skill and

start-up readiness. H2c: ESE resource marshalling significantly mediates the relationship between EE (technical skill, business management skill, personality skill and start-up readiness.

H2d: ESE business implementing significantly mediates the relationship between EE in terms of (a) technical skill, (b) business management skill, (c) personality skill and start-up

readiness. START-UP READINESS Based on the social cognitive theory, start-up readiness is measured from the cognitive element, and personal willingness of an individual to engage in

entrepreneurial activities (Mitchell et al., 2000). In line with this assertion, Lau et al. (2012) define start-up readiness as a person’s cognitive characteristics of capability, and

willingness to act entrepreneurially. In defining entrepreneurial readiness, Coduras et al. (2016) acknowledge the cognitive element as personality traits that differentiate

entrepreneurially inclined individuals with readiness for entrepreneurship, and competence to exploit environmental potentials. This suggests that individuals’ readiness for start-ups

depends on the ability to harness environmental opportunities, and utilises entrepreneurial capability (Olugbola, 2017). This position conforms with the view of Shane et al. (2003) who

assert that the success of any business start-up depends on the entrepreneurial readiness to turn ideas or opportunities into a business enterprise. In this regard, Schillo et al. (2016)

view start-up readiness as a significant force to individuals’ entrepreneurial intention, and individual start-up readiness has been found to have significant association with

entrepreneurial behaviour (Raza et al., 2019). This study argued that potential entrepreneurs are more likely to start a business if they were willing to harness business opportunities and

possess the entrepreneurial capability to succeed in the start-up. There is only a small body of literature on the start-up readiness of young people in Africa, especially within the context

of TVET institutions. The current study aims to fill this gap. ESE AND START-UP READINESS The attainment of a goal for starting a new business is associated with efficacious individuals.

ESE is, perhaps, the most predominant and significant catalyst towards readiness for business start-ups. (Newman et al., 2019; Adeniyi et al., 2022). Empirical bank of data exists on how ESE

improves readiness to engage in entrepreneurial activities. For instance, through an entrepreneurial priming intervention, Bachmann et al. (2021) show how improved level of ESE can increase

positive attitude towards starting a new business venture by comparing two control groups. Gielnik et al. (2020) found that ESE is positively related to business ownership after a year

entrepreneurship training programme for nascent African entrepreneurs. Based on Bandura’s self-efficacy theory, Yusof et al. (2018) found that increase in performance achievement

self-efficacy and verbal persuasion self-efficacy yielded equal increase in Malaysian students’ entrepreneurial intention. The study conducted by Hechavarria et al. (2012) on nascent

entrepreneurs revealed that having a specific goal and higher ESE are related to the establishment of a new business. The authors also found a strong relationship between ESE and business

planning. A multi-construct approach by Nowinski et al. (2019) proves that ESE searching, planning, and marshalling activities mediates the impact of entrepreneurship education on

entrepreneurial intention. However, the study conducted by Mueller and Goic (2003) and Adeniyi et al. (2022) revealed that ESE marshalling shows an insignificant relationship with students’

entrepreneurial readiness to start a new business. Therefore, this study postulates thus: HYPOTHESIS 3 H3: ESE in terms of (a) business searching, (b) business planning, (c) resource

marshalling and (d) business implementing significantly impact start-up readiness for business creation. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK The theory of planned behaviour is arguably the most

predominant concept in determining entrepreneurial behaviour due to its logical ability to predict individuals’ entrepreneurial perception. According to Ajzen (1991), the theory of planned

behaviour is grounded in three underlying predictors of human behaviour. This includes subjective norms (opinions of social relations such as family and friends), attitude towards behaviour

(favourable or unfavourable), and perceived control over the behaviour (ease or impossibility of performing the act). Several studies within entrepreneurship domain have underscored the

three components to comprehend the nature of actual behaviour (Carr and Sequeira, 2007; Kautonen et al., 2015; Gorgievski et al., 2018; Joensuu-Salo et al., 2021; Maheshwari and Kha, 2022).

For instance, Carr and Sequeira (2007) adopted a symbolic interactionist view to demonstrate the relationships between perceived family support, attitudes of nascent entrepreneurs and ESE.

The results indicated that prior exposure to family business shows significant effects on entrepreneurial intention. Kautonen et al.’s (2015) study on 969 adults from Austria and Finland

revealed that attitude, subjective norm and behavioural control were able to predict 59% variations in entrepreneurial intentions. The authors concluded that the theory of planned behaviour

possesses the empirical justification to predict subsequent entrepreneurial intentions and business start-up behaviour (Kautonen et al., 2015). The study conducted by Sabah (2016) among

undergraduate students in Turkey revealed that all variables in the model of TPB show significant support for entrepreneurial intention particularly self-efficacy and personal attitude as

moderated by start-up experience. A cross-country analysis by Gorgievski et al. (2018) suggests that TPB constructs (attitude, social norms and self-efficacy) and value partially mediated

differences in entrepreneurial intentions of 823 students from Netherland, Germany, Poland and Spain. The study by Joensuu-Salo et al. (2021) found that subjective norm shows direct support

for takeover intentions, while the effect of entrepreneurship competence was mediated by attitudes and perceived behavioural control. In addition, empirical findings from Maheshwari and Kha

(2022) found that all components of TPB and ESE significantly and positively mediated the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions. Ajzen (1991) stated

that the concept of perceived behavioural control is most compatible with perceived self-efficacy which influences behavioural actions. This implies that the adopted task related ESE in this

study is best fit into the framework of perceived control (Liñán et al., 2011) which could also be determined by the context of opportunity such as entrepreneurship education towards

business start-ups (Ajzen, 1991). Hence, TPB is a useful tool to underscore the mediating effect of ESE in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness.

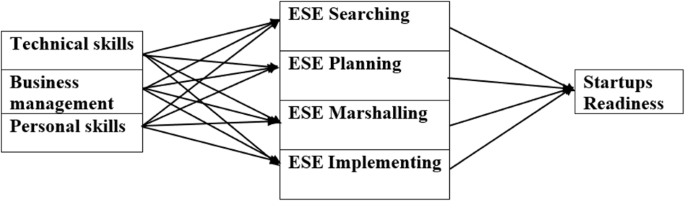

RESEARCH MODEL The model in Fig. 1 below shows the association between entrepreneurship education components (technical skills, business management skills, personality skills) and ESE

task-specific components (searching, planning, marshalling, implementing) (Nowinski et al., 2019). The mediating effects of ESE between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness (Wu

et al., 2022) to create a new business is also addressed in this study. The model also depicts the direct relationship between ESE and start-up readiness. METHODOLOGY This study is

underscored within the positivist philosophical worldview. The scientific principle of hypotheses formulation and validation were applied to determine the entrepreneurial readiness of young

individuals toward starting a business. SAMPLES One of the objectives of this study was to examine the linkages between entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and

start-up readiness within the context of TVET colleges. A survey method was adopted via self-administration of questionnaire to 301 college students from three selected TVET institutions in

Nigeria. The basic mission of establishing TVET colleges was to equip young minds with technical and entrepreneurial skills to become self-employed. Some of the exit level students were

already self-employed at the time of this study. A total of 296 questionnaires were completed but only 289 were valid for analysis due to missing answers. According to Hair et al. (2017), a

minimum sample size of 130 allows a research model with 2 exogenous variables to determine _R_2 coefficient of 0.10 and a 1% level of significance within 80% statistical power, which is

generally applied. Therefore, the sample size in this study justified the use of PLS analysis approach. A little above half (55%) of the sample was male and 45% was female. The age

distribution of the participants was <20 (83%), 20–24 (15.6%), 25–29 (0.7%), and >35 (0.7%). All the participants were sampled from all the designated departments in the selected TVET

colleges. The majority of the sample (30.1%) were from Business Studies department, (17.6%) from Computer Engineering, Automobile Engineering (14.2%), Graphic Arts (9%), Catering (9%),

Mechanical Engineering (8.3%), Bricklaying and Concrete (0.7%), Garment making (0.7%), Electrical Electronic (0.7%), Plumbing and Fittings (5.9%), and Welding and Fabrication (5.9%).

MEASURES ENTREPRENEURSHIP EDUCATION The items of entrepreneurship education used in this study were adapted from Elmuti et al. (2012) who validated the construct by proving that

entrepreneurial behaviour, managerial skills and personal skills are essential for successful business performance. A total of 37 modified items were adopted as measures for entrepreneurship

education. The participants were required to rate the extent to which they possess these skills using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

ENTREPRENEURIAL SELF-EFFICACY ESE was measured using McGee et al. (2009) multi-dimensional ESE scale. The items focused on ESE performance stages (searching, planning, marshalling,

implementing) of becoming nascent entrepreneurs. A total of 19 items were validated with an internal consistency of 0.8 reliability value. Additionally, 22 validated items by Maritz and

Brown (2013) were also adapted for measuring ESE task-specific phases in this study. This makes a total of 33 measuring items for ESE multi-construct. The same 6-point Likert scale was used

as explained above. START-UP READINESS Measures for start-up readiness were adapted from the validated instrument developed by Coduras et al. (2016), which was used to measure an

individuals’ entrepreneurial readiness. The items were scored on the same 6-point Likert scale as mentioned above. DATA ANALYSES First, a test of normality was performed by examining the

skewness and kurtosis of the distribution. As shown in Table 2 above, the coefficient of skewness and kurtosis suggests that the sample is moderately skewed. The skewness shows that all the

values are not within the acceptable range of −0.5 and 0.5 for normal distribution. The value of kurtosis for all the variables was not within the acceptable range of −3 and +3. For this

reason, it is important to conduct a multicollinearity test to further assess variance inflation factors. A dimension reduction process was performed to check for multi-collinearity of the

variables by assessing the Variance Inflation Factors. Results from Table 3 above shows that the variance inflation (VIF) values were all below 10, as well as high tolerance values

(tolerance >0.10). Thus, multi-collinearity was not an issue, and the correlation and Partial least square analysis results can be relied upon. The result of the correlation analysis in

Table 4 revealed that all the components of entrepreneurship education and ESE show significant relationship with start-up readiness. The result also shows that all the dimensions of

entrepreneurship education significantly influence all the dimensions of ESE. Furthermore, Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) from the Smart PLS 4 software (Ringle

et al., 2022; Basco et al., 2022) was used to examine the theoretical model. The PLS-SEM technique is a causal modelling approach that focuses on maximising the variance of the dependent

latent constructs explained by the independent variables (NitzL, 2016; Guenther et al., 2023). Smart PLS has been widely used to measure relationships and mediation effects in various

management and entrepreneurship studies (Kaynak et al., 2015; Cassol et al., 2022; Salameh et al., 2023). MEASUREMENT MODEL The assessment of the reflective measurement models, which applies

to all but one construct in the model, includes indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent and discriminant validity. As shown in Table 1 above, Cronbach’s alpha

and composite reliability values were above 0.7, generally considered acceptable and reflecting internal consistency reliability. As shown in Table 1 above, this study assessed convergent

validity through indicator reliability and average variance extracted (AVE). Regarding indicator reliability, most of the indicator’s standardised outer loadings were above the critical

threshold of 0.7. Two items (_ESEIMP4, SR1_) with extremely low loadings (<0.4) were deleted and the model was rerun. Except for a few constructs, the AVE values were well above the 0.5

threshold, supporting convergent validity (Hair Jr et al., 2022). However, even if AVE was less than 0.5 but composite reliability is higher than 0.6, the convergent validity of the

construct is still adequate (Fornell and Lacker, 1981). In other words, the Composite Reliability establishes that the construct can be retained even when AVE is less than .5. The study

further assessed how well the construct measures discriminate empirically, termed discriminant validity. Table 2 above shows the results of the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) assessment

for discriminant validity, which is superior to both the Fornell and Larcker criterion and the assessment of cross-loadings (Henseler et al., 2015). All but a few HTMT values were higher

than the recommended threshold of 0.90. A bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap confidence interval with 5000 resamples (Cheah et al., 2019) showed that the HTMT values >0.90

were statistically different from 1. These results provide support for discriminating validity for all constructs. To assess the structural model, this study reported the coefficient of

determination (_R_2), path coefficients, and corresponding _p_ values, including their significance tests. The _R_2 values, ranging from 0.542 to 0.702, suggest that the model provided good

explanatory power. The model explained the variation in ESEBUS by 54.2%, ESEPLN by 61.2%, ESEMSH by 54.4%, ESEIMP by 70.2%, and _SR_ by 54%. The _R_2 values are higher than what would

indicate a substantial model. The path analytic results (Table 3 and Fig. 1) showed that ESEBUS was significantly and positively influenced by TS (_β_ = 0.436, _p_ < 0.001) and BMS (_β_ =

0.302, _p_ < 0.01), but an insignificant relationship was found between PS and ESEBUS (_β_ = 034, _p_ > 0.05). Therefore, H1aa and H1ab were accepted, while H1ac was rejected. In a

similar vein, ESEPLN was significantly and positively influenced by TS (_β_ = 0.479, _p_ < 0.001) and BMS (_β_ = 0.283, _p_ < 0.01), but the relationship between PS and ESEPLN shows an

insignificant score (_β_ = 0.061, _p_ > 0.05). Therefore, H1ba and H1bb were accepted, while H1bc was rejected. Additionally, ESEIMP was significantly and positively influenced by TS

(_β_ = 0.355, _p_ < 0.001) and BMS (_β_ = 0.379, _p_ < 0.001), but no significant relationship was found between PS and ESEIMP (_β_ = 0.156; _p_ > 0.05). As result of this, H1ca and

H1cb were accepted, but H1cc was rejected (Fig. 2). However, ESEMSH was significantly and positively influenced by TS (_β_ = 0.238, _p_ < 0.05), BMS (_β_ = 0.287, _p_ < 0.01), and PS

(_β_ = 0.264, _p_ < 0.01). Thus, H1da, H1db, and H1dc were accepted. Examination of the relationship between ESE and SR revealed that SR was significantly and positively influenced by

ESEBUS (_β_ = 0.178, _p_ < 0.05), ESEPLN (_β_ = 0.158, _p_ < 0.05), ESEMSH (_β_ = 0.136, _p_ < 0.05), and ESEIMP (_β_ = 0.340, _p_ < 0.001). Therefore, H3a, H3b, H3c and H3d were

accepted. MEDIATION ANALYSIS: INDIRECT EFFECTS In terms of mediating effects, Table 7 evaluates specific indirect path coefficients and their magnitudes and significance. ESEBUS

significantly (_β_ = 0.078; _p_ < 0.05) mediates the relationship between TS and SR but failed to significantly mediate the relationship between other pairs of entrepreneurship education

(BMS _β_ = 0.054; _p_ > 0.05; and PS _β_ = 0.006; _p_ > 0.05) and SR. Thus, H2aa was accepted, while H2ab and H2ac were rejected. In the same vein, only the relationship between TS and

SR was significantly mediated by ESEPLN (_β_ = 0.075; _p_ < .05), while insignificant relationships were found between other pairs of entrepreneurship education (BMS _β_ = 0.054; _p_

> 0.05; PS _β_ = 0.010; _p_ > 0.05) and SR. Therefore, H2ba was accepted but H2bb and H2bc were rejected. On one hand, ESEIMP significantly mediates the relationship between two pairs

of relationships: TS and SR (_β_ = 0.121; _p_ < 0.01) and BMS and SR (_β_ = 0.129; _p_ < 0.001) but insignificantly mediate the relationship between PS and SR (_β_ = 0.053; _p_ >

0.05). Therefore, H2ca and H2cb were accepted, while H2cc was rejected. On the other hand, ESEMSH shows insignificant mediation between all the components of entrepreneurship education and

SR (TS _β_ = 0.032; _p_ > 0.05; BMS _β_ = 0.039; _p_ > 0.05; PS _β_ = 0.036; _p_ > 0.05). Consequently, H2da, H2db, and H2dc were rejected. DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS Entrepreneurship

is the epicentre of economic prosperity. Entrepreneurship education is the tool that can combat unemployment by providing entrepreneurial skills for employment opportunities and creation of

start-ups. Previous studies have demonstrated that exposure to entrepreneurship education may not necessarily influence individual entrepreneurial intention or self-efficacy (Zhang et al.,

2014; Bae et al., 2014). Accordingly, ESE may not promote entrepreneurial readiness (Nowiński et al., 2019; Adeniyi et al., 2022). Thus, the mediating effects of ESE in the relationship

between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness within developing context remains elusive among young minds in TVET colleges and this requires more empirical validation. The

influence of entrepreneurship education on ESE was investigated. Furthermore, the mediating effects of ESE in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness were

examined in this study. The findings show that ESE business searching, ESE business planning, and ESE business implementing were significantly influenced by technical skills and business

management skills. The significant effects of technical skills, communication, and cognitive skills have been proven to improve entrepreneurial skills among postgraduate students (Salamzadeh

et al., 2022). Entrepreneurial skills such as the ability to search and identify business opportunities, develop business plans, and establish a new business have been reported to increase

students’ ESE (Izquierdo and Buelens, 2011). In some developed contexts, the practice of entrepreneurship education is aimed at enhancing the mechanism associated with ESE (Zhao et al.,

2005). This is evident in the empirical report of Nowiński et al. (2019), in which entrepreneurship education directly and significantly influenced ESE business searching ability, ESE

business planning, and ESE business implementing of university students from Visegrad countries. The finding also supports the report of Zhao et al. (2005) and Dana et al. (2021), in which

learning from entrepreneurship-related modules show significant support for ESE, and tech start-up development in the US. The insignificant relationship between personal skills and ESE

business searching ability, ESE business planning, and ESE business implementing shows the essential need to develop personal entrepreneurial attributes to accomplish specific

entrepreneurial activities. This is consistent with the finding of Cassol et al. (2022), in which entrepreneurship education failed to support determinants of entrepreneurial intention.

However, this result is in contrast with a similar study conducted by Awang et al. (2014), in which personality traits provide support for students’ intention to choose entrepreneurial

career after graduation. Likewise, Boubker et al. (2021) found a significant relationship between entrepreneurship education, attitudes towards entrepreneurship and students’ entrepreneurial

intention. Despite the essential role of entrepreneurship education in skills development, the opportunities are yet to be harnessed in Africa (Herrington and Coduras, 2019). Sabokro et al.

(2018) argue that the lack of basic entrepreneurial skills for task accomplishment is the key factor of an entrepreneur’s failure. One of the perceived learning outcomes of entrepreneurship

education is entrepreneurial skills education. However, several studies suggest that the structure of the entrepreneurship curricular in Africa is deficient of quality content and practical

translations (Nwambam et al., 2018; Jegede and Nieuwenhuizen, 2020), which is one of the causes of low business spin-offs and youth unemployment in the continent (Ogbonna et al., 2022). The

result of this study also validates the significant contribution of entrepreneurship education to ESE marshalling ability, in which all pairs of entrepreneurship education significantly

influence ESE ability to marshal economic resources for start-up readiness. This report buttresses Nowiński et al.’s (2019) finding, in which entrepreneurship education directly contributed

to ESE marshalling ability to enhance university students’ intention. However, previous empirical studies reveal that ESE ability to marshal economic resources failed to provide direct

support for students’ entrepreneurial intention both in developed (Mueller and Goic, 2003) and developing economies (Adeniyi et al., 2022). These results further explain the importance of

entrepreneurship education as a mechanism for strengthening ESE. According to these results, there is evidence to suggest that personal entrepreneurial skills are essential antecedents to

enhance the ability to gather economic resources for start-up readiness, especially in a developing context like Nigeria. Izquierdo and Buelens (2011) noted that higher level

entrepreneurship education would report higher level of ESE, and in turn, more start-up readiness. Entrepreneurship education must address personal entrepreneurial attributes such as

risk-taking, innovativeness and resilience skills towards starting a new business (Ramadani et al., 2022; Hosseini et al., 2022). Previous studies within the developing contexts have

indicated that entrepreneurship education content should incorporate simulation-based training, role play, mentoring and case studies via practical translations (Badri and Hachicha, 2019;

Cassol et al., 2022; Salameh et al., 2023). Examination of the relationship between ESE and SR revealed that SR was significantly and positively influenced by all dimensions of ESE. This

finding further provides support for previous empirical evidence that ESE is a catalyst for start-up readiness (Newman et al., 2019; Bachman et al., 2021), and business ownership (Gielnik et

al., 2020). Besides, the four task-phases of ESE have been validated to stimulate entrepreneurial readiness in a developing context (Adeniyi et al., 2022). This study also revealed that ESE

business implementing ability has the highest score (_β_ = 0.340, _p_ < 0.001) and most significant mediating factor that can stimulate start-up readiness among the students. ESE

business implementing deals with taking business actions such as decision making, managing all human and financial resources, and sustaining the business. It is the most complex

entrepreneurial skill as it deals with a lifelong activity without which other skills are docile. It is worthy of note that implementing a new business in a country like Nigeria requires a

resilience attitude for success. This is evident in the GEM 2019 report, in which government bureaucracies, poor education, lack of access to finance, and corruption put administrative

burdens on start-ups cost (Dvouletý and Orel, 2019). The assessment of the mediating effects of ESE shows that ESE business searching, and ESE planning significantly mediated the

relationship between technical skills and start-up readiness but failed to significantly mediate the relationship between other pairs of entrepreneurship education (business management

skills and personal skills) and start-up readiness. This outcome is in line with Oyugi’s (2015) study, in which the author found that ESE partially mediated the relationship between

entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention. However, the result is quite different from the report of the studies conducted by Hoang et al. (2021) and Wu et al. (2022), in

which all components of ESE completely mediated the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention. This variation justifies the views of Smith and Betz

(2000). The authors provide clarification on the need to strengthen specific self-efficacy within specific career domains such as TVET. This finding also validates that TPB holds in Nigeria.

Increase in favourable perceived behavioural control or ESE increases the chance of start-up readiness especially in technological domain (Azjen, 2020). Accordingly, the partial mediation

effect of ESE indicates the importance of enhancing ESE towards increasing the rate of tech start-ups among science and engineering students, thereby reducing the rate of youth unemployment

in Nigeria. Further investigation indicates that ESE business implementing significantly mediates the relationship between two components of entrepreneurship education (in terms of technical

skills and business management skills) and start-up readiness but shows insignificant relationship between personal skills and start-up readiness. The lack of mediation effect of ESE in the

relationship between personal skills and start-up readiness further justifies the low level of personal entrepreneurial traits of young individuals from the selected TVET colleges. Recall

that apart from ESE marshalling, personal skills show no significant influence with ESE business searching (_β_ = 034, _p_ > 0.05), ESE business planning (_β_ = 0.061, _p_ > 0.05), and

ESE business implementing (_β_ = 0.156; _p_ > 0.05). These findings provide more insights on the importance of developing personal entrepreneurial skills (in terms of risk-taking skills,

innovative skills and resilience skills) for start-up readiness as indicated by various scholars (Almahry and Sarea, 2018; Badri and Hachicha, 2019). Findings from this study have shown the

crucial need to develop personal entrepreneurial attributes toward business start-ups. Accordingly, there is evidence to suggest that entrepreneurship education can build students’

confidence to implement a business start-up. Furthermore, ESE business marshalling did not significantly mediate the relationship between all the components of entrepreneurship education and

start-up readiness. This further suggests the lack of business marshalling ability or resource gathering skill among the selected students from Nigeria. It is worthy of note that the

ability to gather capital, employees, suppliers, and assets for business creation is a major challenge for nascent entrepreneurs in Nigeria. This is because the entrepreneurial ecosystem in

Nigeria is entrepreneurially hostile as student-entrepreneurs often struggle to access financial support to grow their new start-ups. Access to finance is a major challenge for potential

entrepreneurs in Africa, including Nigeria (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2019). Some of the nascent entrepreneurs who managed to secure loans from financial institutions still struggle

to grow the business due to stringent economic policies such as high interest rates on loans and high tax rates. To this end, extant literature revealed that nascent entrepreneurs

demonstrate higher tax evasion compared to established entrepreneurs (Batrancea et al., 2022), and this, perhaps is as a result of lack of intrinsic motivation to comply to pay (Ramona-Anca

and Larissa-Margareta, 2013). CONTRIBUTION HIGHLIGHTS * The findings revealed that entrepreneurship education shows a partial relationship with ESE. * ESE partially mediates the relationship

between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness. * Personal entrepreneurial skills are essential antecedents that can enhance the ability to gather economic resources for business

start-ups. * Another contribution of this study indicates that there is need for universities and entrepreneurship professionals to improve the level of social cognitive value (personal

entrepreneurial traits) among young individuals in Nigeria. THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS This is one of the first studies to examine the mediating effects of ESE among students of TVET colleges

in a developing context. This study provides empirical evidence that ESE is best measured as a multidimensional construct (McGee et al., 2009). Different from Nowiński et al. (2019), which

focused on the relationship between entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, gender and entrepreneurial intention, and Wu et al. (2022), which examined the relationship

between entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intention, a multi-construct entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy effects on

start-up readiness were examined in this study. The finding that entrepreneurship education provides partial support for ESE towards start-up readiness has some important implications. The

insignificant relationships between personal entrepreneurial skills and ESE, and partial mediating effect of ESE in the relationship between personal entrepreneurial skill and start-up

readiness, shows the low level of social cognitive value compared to human capital value. Previous study has shown that human capital value is more associated with organisational performance

(Aman-Ullah et al., 2022), while social cognitive value is concerned with embedded personality traits and use of personal initiative to accomplish a task for goal achievement (Bandura,

1994; Maddux, 2013). The insignificant mediation effect of ESE marshalling in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness validates the reports from previous

studies on the demand for resource gathering skills among young people (Mueller and Goic, 2003; Adeniyi et al., 2022). Findings from this study revealed areas of strength and weakness for

both ESE and entrepreneurship education in relation to starting a new business by examining different components of both constructs. Another contribution from this study is the finding that

personal entrepreneurial skills are cognitive elements that can stimulate resource gathering ability for start-up readiness. This is a contribution to identified gaps in previous studies

which provided little understanding on the specific stimulating factors of entrepreneurial success. MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS Firstly, the examination of dimensions of entrepreneurship

education and ESE task-activities indicates a partial relationship. Mostly, personal entrepreneurial skills did not show support for ESE searching, ESE planning, and ESE implementing.

Entrepreneurship educators and policy makers should consider these dimensions for creating a new business when designing entrepreneurial curricula. Traditional entrepreneurship education

focuses on knowledge in business and management skills, the insignificant role of personal skills suggests that educators place greater emphasis on personality traits of students regarding

entrepreneurship activities. Based on the outcome of this study, the partial and positive mediating role of ESE dimensions suggests the importance of promoting task-related entrepreneurial

activities for creating new start-ups. The low level of resource gathering skills for start-up readiness should be addressed through practical entrepreneurial engagements. Economic

indicators such as sound monetary policy (inflation and tax regulations) and business regulations (credit and labour) (Bătrâncea and Nichita, 2015) should be made flexible and suitable for

new start-ups to thrive. CONCLUSION Several studies have shown that ESE significantly mediated the relationship between entrepreneurship education and intentions (Yang, 2020; Maheshwari and

Kha, 2022; Al-Qadasi et al., 2023). The mediating effect of ESE between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness in developing context is under-researched, especially in Sub-Saharan

Africa. Therefore, this study contributed to existing knowledge by demonstrating the contributing effects of ESE to business start-ups. This finding suggests that the more confident young

people become in their ability to engage in entrepreneurship, the more their interest toward entrepreneurial activity. Therefore. The adopted dimensions of ESE adopted in this study should

be considered as an essential part of entrepreneurship education. This study also contributes to previous studies on the importance of promoting personal entrepreneurial attributes for

entrepreneurial careers. Thus, exposing students to entrepreneurship at an early stage can help develop positive entrepreneurial traits from their formative years toward starting a new

business and initiating new ideas within existing firms (Izquierdo and Buelens, 2011). This study also demonstrates the direct effect of entrepreneurship education on ESE. The partial

contribution of entrepreneurship education to ESE implies the crucial need to activate learning by doing in entrepreneurship education. The pedagogical approach can incorporate real life

experience and business case activities via practical engagements (Tables 5–7). LIMITATIONS OF STUDY AND FUTURE RESEARCH Cross-sectional data were used to validate the hypotheses and examine

the association between entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and start-up readiness. However, the causal relationships were not proven. Future research should

re-examine these relationships from a longitudinal perspective. McGee and Peterson’s (2019) study on the influence of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial performance, with the

collection of data at three specific given times revealed that time lag mitigated the influence of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial performance. The length of time after

school has been reported to affect readiness to start a new business. Longitudinal study during and after school would help to clarify the relationship between entrepreneurship education,

entrepreneurial self-efficacy and start-up readiness within the developing context. DATA AVAILABILITY The data set is available on the Humanities and Social Sciences Communications Dataverse

repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MKQUIY. CHANGE HISTORY * _ 22 JANUARY 2024 A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02679-1 _ REFERENCES *

Adeniyi AO (2021) Psychosocial determinants of entrepreneurial readiness: the role of TVET institutions in Nigeria. Doctoral thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal Google Scholar * Adeniyi AO,

Derera E, Gamede V (2022) Entrepreneurial self-efficacy for entrepreneurial readiness in a developing context: a survey of exit level students at TVET Institutions in Nigeria. SAGE Open

12(2):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221095059 Article CAS Google Scholar * Ahmed T, Chandran VGR, Klobas JE et al. (2020) Entrepreneurship education programmes: how learning,

inspiration and resources affect intentions for new venture creation in a developing economy. Int J Manag Educ 18(1):100327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.100327 Article Google

Scholar * Ajzen I (2020) The theory of planned behavior: frequently asked questions. Hum Behav Emerg Technol 2(4):314–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195 Article Google Scholar * Ajzen

I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T Article Google Scholar * Almahry FF, Sarea AM (2018) A

review paper on entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurs’ skills. J Entrep Educ 21(2):1–7.

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/AdelSarea/publication/338300642/links/5e569d514585152ce8f25e85/.pdf * Al-Qadasi N, Zhang G, Al-Awlaqi MA et al. (2023) Factors influencing

entrepreneurial intention of university students in Yemen: the mediating role of entrepreneurial self- efficacy. Front Psychol 14:1111934. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1111934 Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Aman-Ullah A, Mehmood W, Amin S et al. (2022) Human capital and organizational performance: a moderation study through innovative leadership. J

Innov Knowl 7(4):100261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100261 Article Google Scholar * Awang A, Ibrahim II, Ayub SA (2014) Determinants of entrepreneurial career: experience of

polytechnic students. J Entrep Bus Econ 2(1):21–40. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265328217 Google Scholar * Bachmann AK, Maran T, Furtner M (2021) Improving entrepreneurial

self-efficacy and the attitude towards starting a business venture. Rev Managerial Sci 15:1707–1727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-020-00394-0 Article Google Scholar * Badri R, Hachicha N

(2019) Entrepreneurship education and its impact on students’ intention to start up: a sample case study of students from two Tunisian universities. Int J Manag Educ 17(2):182–190.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.02.004 Article Google Scholar * Bae TJ, Qian S, Miao C et al. (2014) The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions:

a meta–analytic review. Entrep Theory Pract 38(2):217–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12 Article Google Scholar * Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: a social

cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall * Bandura A (1994) Self-efficacy. In: Ramachaudran VS (ed) Encyclopedia of human behavior. Academic Press, New York, NY, p 71–81 Google

Scholar * Barbosa SD, Gerhardt MW, Kickul JR (2007) The role of cognitive style and risk preference on entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions. J Leadership Organ Stud

13(4):86–104 Article Google Scholar * Basco R, Hair Jr JF, Ringle CM et al. (2022) Advancing family business research through modeling nonlinear relationships: comparing PLS-SEM and

multiple regression. J Fam Bus Strategy 13(3):100457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2021.100457 Article Google Scholar * Bătrâncea L, Nichita A (2015) Which is the best government?

Colligating tax compliance and citizens’ insights regarding authorities’ actions. Transylv Rev Adm Sci 11(44):5–22 Google Scholar * Bătrâncea LM, Kudła J, Błaszczak B et al. (2022)

Differences in tax evasion attitudes between students and entrepreneurs under the slippery slope framework. J Econ Behav Organ 200:464–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2022.06.017 Article

Google Scholar * Bieschke KJ (2006) Research self-efficacy beliefs and research outcome expectations: Implications for developing scientifically minded psychologists. J Career Assess

14(1):77–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072705281366 Article Google Scholar * Boubker O, Arroud M, Ouajdouni A (2021) Entrepreneurship education versus management students’

entrepreneurial intentions. A PLS-SEM approach. Int J Manag Educ 19(1):100450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100450 Article Google Scholar * Boyd NG, Vozikis GS (1994) The influence

of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep Theory Pract 18(4):63–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879401800404 Article Google Scholar * Carr JC,

Sequeira JM (2007) Prior family business exposure as intergenerational influence and entrepreneurial intent: a theory of planned behavior approach. J Bus Res 60(10):1090–1098.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.12.016 Article Google Scholar * Cassol A, Tonial G, Machado HPV et al. (2022) Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions and the moderation of

entrepreneurial education: a study of the Brazilian context. Int J Manag Educ 20(3):100716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100716 Article Google Scholar * Cheah JH, Ting H, Ramayah T

(2019) A comparison of five reflective–formative estimation approaches: reconsideration and recommendations for tourism research. Qual Quantity 53:1421–1458.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-018-0821-7 Article Google Scholar * Chen CC, Greene PG, Crick A (1998) Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J Bus

Ventur 13(4):295–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00029-3 Article Google Scholar * Chigunta F (2017) Entrepreneurship as a possible solution to youth unemployment in Africa.

Laboring Learn 10(2):433–451 Article Google Scholar * Coduras A, Saiz-Alvarez JM, Ruiz J (2016) Measuring readiness for entrepreneurship: an information tool proposal. J Innov Knowl

1(2):99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2016.02.003 Article Google Scholar * Dana LP, Tajpour M, Salamzadeh A et al. (2021) The impact of entrepreneurial education on technology-based

enterprises development: the mediating role of motivation. Adm Sci 11(4):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11040105 Article Google Scholar * De Noble A, Jung D, Ehrlich S (1999)

Initiating new ventures: the role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. In: Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 1999. Available at www.Babson. Accessed January 2023 * Drnovšek M, Wincet J,

Cardon MS (2010) Entrepreneurial self‐efficacy and business start‐ up: developing a multi‐dimensional definition. Int J Entrep Behav Res 16(4):329–348.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551011054516 Article Google Scholar * Dvouletý O, Orel M (2019) Entrepreneurial activity and its determinants: findings from African developing countries. In:

Ratten, V., Jones, P., Braga, V., Marques, C.S. (eds) Sustainable entrepreneurship: the role of collaboration in the global economy. Springer, Cham, p 9–24 * Edokpolor JE, Owenvbiugie RO

(2017) Technical and vocational education and training skills: an antidote for job creation and sustainable development of Nigerian economy. Probl Educ 21st Century 75(6):535 Article Google

Scholar * Elmuti D, Khoury G, Omran O (2012) Does entrepreneurship education have a role in developing entrepreneurial skills andventures’ effectiveness? J Entrep Educ 15:83–104.

https://fada.birzeit.edu/handle/20.500.11889/2670 * European Commission (2012) Effects and impact of entrepreneurship programs in higher education. Brussels (2012) European Unit.

[email protected] * Fayolle A, Gailly B (2015) The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: hysteresis and persistence. J Small Bus

Manag 53(1):75–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12065 Article Google Scholar * Fayolle A (2018) Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education. In Fayolle A (ed). A research

agenda for entrepreneurship education. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 127–138. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781786432919.00013 * Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural

equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104 Article Google Scholar * Gedeon SA, Valliere D (2018)

Closing the loop: Measuring entrepreneurial self-efficacy to assess student learning outcomes. Entrep Educ Pedagogy 1(4):272–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127418795308 Article Google

Scholar * Gielnik MM, Bledow R, Stark MS (2020) A dynamic account of self-efficacy in entrepreneurship. J Appl Psychol 105(5):487–505 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Gorgievski MJ,

Stephan U, Laguna M et al. (2018) Predicting entrepreneurial career intentions: values and the theory of planned behavior. J Career Assess 26(3):457–475.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072717714541 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2017) Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2017. United States, MA: Babson College *

Grabowski LJS, Call KT, Mortimer JT (2001) Global and economic self-efficacy in the educational attainment process. Soc Psychol Qly 64(2):164–179 Article Google Scholar * Guenther P,

Guenther M, Ringle CM et al. (2023) Improving PLS-SEM use for business marketing research. Ind Mark Manag 111:127–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2023.03.010 Article Google Scholar

* Hair Jr JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM et al. (2022) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd edn. Sage Publications, USA Google Scholar * Hair Jr JF,

Matthews LM, Matthews RL et al. (2017) PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: updated guidelines on which method to use. Int J Multivariate Data Anal 1(2):107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

Article Google Scholar * Hampel-Milagrosa A (2010) Identifying and addressing gender issues in doing business. Eur J Dev Res 22:349–362 Article Google Scholar * Hechavarria DM, Renko M,

Matthews CH (2012) The nascent entrepreneurship hub: goals, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and start-up outcomes. Small Bus Econ 39:685–701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9355-2 Article

Google Scholar * Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based Structural Equation Modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43:115–135.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8 Article Google Scholar * Henry C, Hill F, Leitch C (2005) Entrepreneurship education and training: can entrepreneurship be taught? Part II,

Emerald Group Publishing Limited 47(3):158–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910510592211 Article Google Scholar * Herrington M, Coduras A (2019) The national entrepreneurship framework

conditions in sub- Saharan Africa: a comparative study of GEM data/National Expert Surveys for South Africa, Angola, Mozambique and Madagascar. J Glob Entrep Res 9:1–24.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0183-1 Article Google Scholar * Hien DTT, Cho SE (2018) Relationship between entrepreneurship education and innovative start-up intentions among

university students. Int J Entrep 22(3):1–16 ADS Google Scholar * Hisrich RD, Peters MP (1998) Entrepreneurship, 4th ed., Irwin McGraw-Hill, Boston, MA * Hoang G, Le TTT, Tran AKT, Du T

(2021) Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Vietnam: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning orientation,. Educ Training

63(1):115–133. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2020-0142 Article Google Scholar * Hosseini E, Tajpour M, Salamzadeh A, et al. (2022) Team performance and the development of Iranian digital

start-ups: the mediating role of employee voice. In: Managing human resources in SMEs and Start-ups. International challenges and solutions. World Scientific, p 109–140 * ILO (2018) World

employment and social outlook – trends 2023. Available at. https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_615590/lang--en/index.htm * Izquierdo E, Buelens M (2011) Competing

models of entrepreneurial intentions: the influence of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and attitudes. Int J Entrep Small Bus 13(1):75–91 Google Scholar * Jack S, Anderson AR (1999)

Entrepreneurship education within the enterprise culture producing reflective practitioners. Int J Entrep Behav Res 5(3):110–125. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552559910284074 Article Google

Scholar * Jegede OO, Nieuwenhuizen C (2020) Factors influencing business start-ups based on academic research. https://hdl.handle.net/10210/458039 * Joensuu-Salo S, Viljamaa A, Varamäki E

(2021) Understanding business takeover intentions—the role of theory of planned behavior and entrepreneurship competence. Admin Sci 11(3):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030061 Article

Google Scholar * Kautonen T, Van Gelderen M, Fink M (2015) Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep Theory Pract

39(3):655–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12056 Article Google Scholar * Kaynak R, Sert T, Sert G et al. (2015) Supply chain unethical behaviors and continuity of relationship: using the

PLS approach for testing moderation effects of inter-organizational justice. Int J Prod Econ 162:83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.01.010 Article Google Scholar * Kumar R, Shukla

S (2022) Creativity, proactive personality and entrepreneurial intentions: examining the mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Glob Bus Rev 23(1):101–118.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150919844395 Article Google Scholar * Lau VP, Dimitrova MN, Shaffer MA (2012) Entrepreneurial readiness and firm growth: an integrated ethic and emic approach.

J Int Manag 18(2):147–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2012.02.005 Article Google Scholar * Lent RW, Maddux JE (1997) Self-efficacy: building a socio-cognitive bridge between social

and counseling psychology. Counsel Psychol 25(2):240–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000097252005 Article Google Scholar * Liñán F, Santos FJ, Fernández J et al. (2011) The influence of

perceptions on potential entrepreneurs. Int Entrep Manag J 7:373–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-011-0199-7 Article Google Scholar * Maddux JE (ed) (2013) Self-efficacy, adaptation,

and adjustment: theory, research, and application. Springer Science and Business Media Google Scholar * Maheshwari G, Kha KL (2022) Investigating the relationship between educational

support and entrepreneurial intention in Vietnam: the mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the theory of planned behavior. Int J Manag Educ 20(2):100553.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100553 Article Google Scholar * Maritz A, Brown C (2013) Enhancing entrepreneurial self-efficacy through vocational entrepreneurship education

programmes. J Vocat Educ Training 65(4):543–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2013.853685 Article Google Scholar * Martin G, Pear J (2015) Behavior modification: what it is and how to

do it? (10th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: PrenticeHall, Inc * McGee JE, Peterson M (2019) The long-term impact of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial orientation on venture

performance. J Small Bus Manag 57(3):720–737 Article Google Scholar * McGee JE, Peterson M, Mueller SL et al. (2009) Entrepreneurial self–efficacy: refining the measure. Entrep Theory

Pract 33(4):965–988. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00304.x Article Google Scholar * McKinsey Global Institute (2017) A future that works: automation employment and productivity.

https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/170622-slides-manyika.pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2023 * McKinsey Global Institute (2022) Reimagining economic growth in Africa: turning

diversity into opportunity. Available at https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/reimagining-economic-growth-in-africa-turning-diversity-into-opportunity * Mitchell RK, Smith B, Seawright

KW et al. (2000) Cross-cultural cognitions and the venture creation decision. Acad Manag J 43(5):974–993. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556422 Article Google Scholar * Mozahem NA, Adlouni RO

(2021) Using entrepreneurial self-efficacy as an indirect measure of entrepreneurial education. Int J Manag Educ 19(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100385 Article Google

Scholar * Mueller SL, Goic S (2003) East-West differences in entrepreneurial self-efficacy: Implications for entrepreneurship education in transition economies. Int J. Entrep Educ

1(4):613–632 Google Scholar * National Bureau of Statistics (2023) Youth unemployment rate in Nigeria. Available at.

https://nationalplanning.gov.ng/fg-inaugurates-committee-to-tackle-increasing-youth-unemployment-in-nigeria/ * Newman A, Obschonka M, Schwarz S et al. (2019) Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: a

systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. J Vocat Behav 110:403–419.