- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT This study investigates the emotional management strategies employed by the Chinese maintream media _Huanqiu Shibao (HQSB)_, through the use of nationalistic rhetoric during the

Covid-19 pandemic. By conducting a discourse analysis of the coverage of Covid-19 on _HQSB_’s WeChat account, this research reveals two primary emotional management strategies: defensive

nationalism and aggressive nationalism. Defensive nationalism utilizes fear and positive emotions to uphold and defend Chinese politics, while aggressive nationalism employs disgust to

counter external criticisms and delegitimize the US democratic system and international leadership. By examining how _HQSB_ emotionally differentiates the world, the study unveils that

tactics Chinese mainstream media use to construct national identity, drawing a divisive line between a despised ‘them’ and an innocent ‘us’. The Covid-19 pandemic presents a unique

opportunity to reflect on the emotionalisation of Chinese digital propaganda and the evolution of state-led nationalism during a public health crisis. The research concludes that the use of

emotion in _HQSB_’s Covid-19 coverage aligns with China’s broader strategy of nation-building and global influence promotion. It underscores the need for greater awareness of the emotional

mobilization used in political communication, particularly during times of crisis. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE ROLE OF EMOTION AND SOCIAL CONNECTION DURING THE COVID-19

PANDEMIC PHASE TRANSITIONS: A CROSS-CULTURAL COMPARISON OF CHINA AND THE UNITED STATES Article Open access 08 February 2024 IMAGE RESTORATION STRATEGIES IN PANDEMIC CRISIS COMMUNICATION: A

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF CHINESE AND AMERICAN COVID-19 POLITICAL SPEECHES Article Open access 04 October 2024 EXPOSURE TO A MEDIA INTERVENTION HELPS PROMOTE SUPPORT FOR PEACE IN COLOMBIA

Article 14 April 2022 INTRODUCTION Emotions have long played a significant role in sustaining authoritarian rule. Previous studies have explored how mainstream media in authoritarian states

mobilizes emotions such as fear (Huang, 2015, 2018), pride (Greene and Robertson, 2020), and gratitude (Chen and Wang, 2019) to enhance regime legitimacy. In the context of China, the

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) government has been found to use emotions of sorrow and humiliation in national identity building and regime legitimation (Callahan, 2004; Wang, 2008; Zhao,

1998). Recent scholarship has observed a shift towards more positive emotions in Chinese official propaganda. Emotions such as pride, gratitude, and optimism are being utilized to cultivate

loyalty and voluntary obedience to the party-state regime (Chen et al., 2021; Chen and Wang, 2019; Yang and Tang, 2018). The Covid-19 pandemic presents a unique opportunity to examine the

emotional management strategies of the Chinese government (Zhang, 2022). Amid accusations regarding its delayed response, strict lockdown policy, and stringent censorship measures, Chinese

mainstream media has proven adept at deflecting external criticism—particularly from the United States—and rechanneling internal dissatisfaction into regime-supportive nationalism (Jacob,

2020; Song and Liu, 2022). This transformation of public distrust and disappointment into regime confidence and solidarity illuminates authoritarian resilience in communication (de Kloet et

al., 2021; Song and Liu, 2022), particularly within the context of Sino-American political tension. While previous studies have observed the co-evolution of public emotions and nationalistic

discourse on China’s digital landscape during the pandemic (de Kloet et al., 2021; Zhang, 2022; Zhang and Xu, 2022; Yang and Chen, 2021), few have examined the mechanisms by which Chinese

official propaganda incorporates emotional management with nationalistic discourse. To map the affective pandemic governance strategies of official Chinese propaganda, we conducted a

discourse analysis of 158 posts from the official Wechat account of _Huanqiu Shibao_’s (_HQSB_), focusing particularly on the representation of the United States as the primary ‘other’.

_HQSB_ was chosen due to its status as an official media outlet and its nationalistic market positioning (Larson, 2011; Zeng and Sparks, 2020). We chose to analyze its WeChat account over

its newspaper format because the former reaches a larger audience base with its concise, entertaining, and interactive style. Our research unveils two main strategies in Chinese official

propaganda’s affective governance: defensive nationalism and aggressive nationalism. While defensive nationalism is enacted through the integration of fear, praise, and joy from both

domestic and international realms to defend Chinese politics, aggressive nationalism is enacted through the manipulation of disgust to neutralize external criticisms, primarily from the US,

and delegitimize its democratic system and international leadership through the demonstration of fury, astonishment, and disappointment from within American society. These strategies should

be understood within the broader context of ongoing Sino-American political tensions. These tensions have been intensified due to various issues including trade disputes, human rights

concerns, technology and intellectual property theft, as well as geopolitical tensions in regions like the South China Sea. Such tensions have fostered a heightened sense of rivalry and

opposition between the two countries, influencing their respective domestic and international narratives. In particular, these dynamics significantly inform the portrayal and perception of

the United States within Chinese official propaganda. The charged emotions and nationalistic sentiments that such propaganda aims to evoke are embedded in these larger political dynamics,

with the US often depicted as an adversary, challenge, or threat to China’s national identity and regime legitimacy. This paper demonstrates a convergence between the global distribution of

power and emotional gravity in global imaginaries constructed by Chinese mainstream media. Contrary to the monolithic presumption about Chinese official propaganda, _HQSB_ adopts a more

complex emotional management mechanism that amalgamates negatively sentimentalized victimhood, positively charged pride, and even a sense of superiority. Transcending the conventional focus

of propaganda studies on domestic political information management, this paper contributes to unpacking the emotional-discursive mechanism that official Chinese propaganda uses to transform

international news, particularly those related to the US, into domestically relevant propagandist content. By explicitly identifying and emphasizing the role of the United States as the

primary ‘other’, this study provides a more nuanced understanding of the emotional strategies utilized by official Chinese propaganda during global crises. EMOTION POLITICS IN CHINA The

mobilization of emotions in the Chinese propaganda system to facilitate nation-building and enhance regime legitimacy has been extensively studied. Research suggests that the CCP has

employed a model of “emotion work,” utilizing emotions such as fear, grief, rage, and shame to exert a sustainable influence on contemporary Chinese politics (Perry, 2002). In the post-Mao

era, as the ideological foundation of the CCP shifted from Marxism to a combination of nationalism, meritocracy, and traditionalism (Zeng, 2014), emotional management strategies took on a

humiliation-focused approach. Emerging from China’s tumultuous encounters with Western and Japanese invaders, the narrative of national humiliation activates a collective sense of shame

about China’s loss of territory and prestige, fostering a common aspiration to regain its status as a great power (Wang, 2008). The ‘century of humiliation’ serves as a linear narrative that

connects China’s historical glory with its contemporary resurgence, perpetuating a recurring fear of the external “other” represented by Western imperialism, as well as an internal “other”

embodied by the underperforming “self” (Callahan, 2004). In the 1990s, in response to the ideological challenge posed by the Tiananmen Square incident, the CCP government initiated the

“patriotic education campaign,” which packaged China’s suffering as a confrontation with foreign atrocities, imbuing it with a narrative of victimization (Wang, 2008). This initiative in

memory management constructs a self-victimized national identity among the younger Chinese generation, contributing to the legitimization of CCP rule and fostering a sense of social

solidarity (Zhang, 2020). While shame politics served as a prominent and effective ideological tool for cohering society under CCP rule in the 1990s (Zhao, 1998), compassion politics became

the predominant approach to emotion management during the Hu-Wen government’s tenure. Xu (2018) observes that Chinese nationalism softened considerably during this era, evident notably

during the Sichuan Earthquake. Official mourning rituals surrounding the natural disaster not only demonstrated the leadership’s paternalistic compassion but also fostered a confident

sentiment regarding the capacity of the socialist political system. Under Xi Jinping’s leadership, the emotional tone of Chinese official propaganda has shifted to the concept of “positive

energy.” At the collective level, the “wolf warrior” spirit fuels national pride and confidence in celebrating China’s strength (Shi and Liu, 2019; Sullivan and Wang, 2022). At the

individual and societal levels, gratitude, generosity, and altruism are encouraged to address dissatisfaction stemming from social inequality and conflicts (Chen and Wang, 2019). At the

political level, nationalism, trust in the government, and confidence in the socialist system with Chinese characteristics are mobilized to align public emotions with the “ideological and

value systems of the CCP party-state” (Yang and Tang, 2018: 3). Contextualizing the “positive energy” campaign within a neoliberal emotion management regime, this strategy can be seen as an

inherent characteristic of affective biopolitics in Foucauldian terms, disciplining citizens into docile subjects who internalize state interests and manifest affective responses aligned

with state expectations (Chen and Wang, 2019; Hird, 2018). Chinese scholars have coined the term “emotion-setting” to describe the transition of Chinese official propaganda from

“agenda-setting” to emotion-setting (Gao and Wu, 2019). As noted by Gries (2004), contemporary Chinese nationalism has dynamically evolved in its relationship with other nations and its own

historical narrative. The current sense of pride evident in Chinese nationalism is projected onto an imagined ever-renewing Western “other” and a shameful past “self.” Increasing literature

suggests that younger generations in China are embracing a more empowering and positively oriented nationalistic sentiment, favoring empowerment rather than passive victimization (Guan and

Hu, 2020). THE EMOTIONAL MANAGEMENT OF CHINESE PANDEMIC PROPAGANDA A public health crisis elicits a range of collective emotions, including fear, anxiety, and anger. These emotions can

intensify to the point where they lead to feelings of distrust and suspicion towards the domestic government, as well as exclusionary nationalism against perceived “others” (Mylonas and

Whalley, 2022; Zhou and Xie, 2022). In the case of China, the management of the COVID-19 pandemic has attracted particular scrutiny due to the government’s delayed response, lack of

transparency, censorship, and strict containment measures, which have generated significant dissatisfaction and anger from both domestic and international audiences. The outbreak of COVID-19

provided the CCP with an opportunity to exercise affective governance, directing public fear and anxiety towards collective trust and confidence in the authoritarian regime (Sorace, 2021;

Zhang and Jamali, 2022: Zhang et al., 2023). In response to the initial wave of public fear, anxiety, and panic, the government redirected its own uncertainty and insecurity towards

legitimizing the strict containment measures (de Kloet et al., 2021). In response to public dissatisfaction with the government’s handling of whistleblower Dr. Li Wenliang, the CCP

implemented punitive measures against local officials who attempted to assuage public anger and redirect resentment (Zhang, 2020). Furthermore, the CCP invoked the classical model of

disaster nationalism (Schneider and Hwang, 2014) by posthumously declaring Dr. Li Wenliang a “martyr,” positioning him as a hero who sacrificed his life during the pandemic to counter the

prevailing public narrative that portrayed him as a champion of free speech. This strategy effectively demobilized public outrage and redirected dissent towards regime-supportive nationalism

(Song and Liu, 2022). By downplaying its own mismanagement of information during the initial outbreak and demonstrating paternalistic compassion, the government aimed to assuage grief and

temper public anger (Zhang, 2022). In addition to traditional techniques such as highlighting exemplary individuals, the CCP has championed ordinary citizens as part of its strategy. Through

media coverage and the portrayal of everyday people as “heroes” in the fight against COVID-19, state-sponsored media has created an image of citizens voluntarily cooperating with the

government and embracing a patriotic ethos aligned with the CCP (Xie and Zhou, 2021). Extensive coverage of medical workers as national heroes by state-owned media fostered a sense of

solidarity among the collective “we,” encouraging unity and resilience in overcoming the crisis under CCP leadership (de Kloet et al., 2021). As contagion rates within mainland China

declined and the number of COVID-19 cases globally continued to rise, Chinese affective governance shifted towards externally focused, exclusionary nationalism. This transformation, driven

by a politics of pride, with the Chinese government emphasizing national achievements in combating the virus, juxtaposed against the high death toll and extended quarantine measures

implemented in the West (de Kloet et al., 2021). These accomplishments reinforced the belief that effective biopolitical containment measures demonstrated the superiority of the Chinese

political system and geopolitical prowess, fueling a sense of “biopolitical nationalism” within China (de Kloet et al., 2020). Moreover, this sense of triumph over the West is propagated

through the lens of the “century of humiliation,” transforming the initial shame of the pandemic’s outbreak into a form of “anti-imperialist nationalism” (Jaworsky and Qiao, 2021). To

amplify nationalistic fervor, Chinese national media portrays Western countries as intentionally malicious and inefficient in their handling of the pandemic, fostering enmity, resentment,

and contempt among domestic citizens towards this imagined rival (Zhang, 2022). A systematic content analysis of China Daily, People’s Daily, and Xinhua News’ coverage of COVID-19 confirms

that Chinese English-language official media employs the enemification of the United States, victimization narratives, and heroization of China to resist foreign criticisms and repair

China’s national image (Yu, 2022). Furthermore, the Chinese government’s commitment to providing free vaccinations domestically and affordable vaccines internationally is utilized to instill

‘vaccine nationalism,’ generating greater confidence in the authoritarian regime and fostering pride in China’s global leadership (Zhang and Jamali, 2022; Zhao, 2021). This expression of

nationalism is blended with globalism, constructing a binary between “us” and “them” (Yang and Chen, 2021). While previous studies have touched upon the emotional management strategies of

the Chinese government, primarily focusing on formal news formats of main official news outlets, the expressions of Chinese official propaganda on social media platforms have been relatively

underexplored. This article fills this gap by examining the emotional management strategies employed by the nationalistic tabloid _HQSB_ through an analysis of its WeChat posts. The study

seeks to answer the following question: How does _HQSB_ enact emotional management through nationalistic discourse? DATA COLLECTION This research examines the impact of Chinese state-funded

propaganda’s affective governance during the Covid-19 pandemic by analyzing coverage of the pandemic on the _HQSB_ WeChat platform from the start of 2020 to the beginning of 2021. _HQSB_ was

chosen as a case study due to its affiliation with People’s Daily, China’s most authoritative party press, and its reputation as a Chinese equivalent of “Fox News” (Larson, 2011). _HQSB_

uses provocative commentaries, eye-catching headlines, and a “crimson banner” style to engage a wide Chinese-speaking audience, effectively shaping public opinion (Hatef and Luqiu, 2018).

Thus, _HQSB_ provides a useful lens for researchers to investigate the Chinese government’s mobilization of nationalistic sentiments. Data for the study was collected from _HQSB_’s official

WeChat account, given the platform’s widespread popularity and _HQSB_’s significant presence on it. With over one billion monthly active users worldwide, WeChat has become a crucial

infrastructure that shapes people’s political, economic, and social lives in China (Stancheva, 2021). To compete for attention in this highly competitive environment, Chinese state-funded

propaganda, including _HQSB_, has adapted to a sensationalized information style, incorporating clickbaits and emotionally evocative expressions in their WeChat public accounts (Lu and Pan,

2021; Zou, 2021). _HQSB_’s public account, launched on the WeChat platform in 2013, consistently ranks as the most popular “current affairs” account on Newsrank’s daily and weekly rankings

(an independent social media monitoring agency) (Newsrank, 2022). Therefore, the coverage of the pandemic on _HQSB_’s WeChat account holds significant value in elucidating the affective

governance strategies employed by Chinese propaganda during the pandemic. To address our research question, we compiled a sample of 158 articles from _HQSB_’s public WeChat account between

January 1st, 2020 (the day after the World Health Organization was first informed of a cluster of cases) and February 16th, 2021 (the date when our data collection ended). This period covers

the transformation of Covid-19 from a local health crisis to a global pandemic, during which the Chinese government’s affective governance strategies evolved in different stages. We

conducted the following steps to screen the WeChat posts: firstly, we used the keyword “新冠“ (Covid) to retrieve articles and saved 227 articles that contained at least one mention of a

foreign country to ensure their international focus. Secondly, as our objective was to investigate _HQSB_’s emotional management, we reviewed our database and removed 69 news bulletins

without emotional content. The reason we include commentary and screen news bulletins is that news bulletin tend to convey neutral news without emotional or attitudinal message. As we intend

to examine the utilization of emotion in domestic propaganda, we excluded out news bulletins due to their limited containment of emotional expression. We then uploaded the remaining 158

articles that exhibited emotional content to NVivo for further analysis. DATA ANALYSIS To identify patterns of emotion distribution in the corpus, we coded the texts using seven emotions.

Our codebook (see Supplementary Appendix) was based on Ekman’s (1992) classical emotion classification, supplemented by Luo and his colleagues’ (2014) Sinicized operationalization. Ekman’s

research identified six types of emotions in facial expressions: happiness, surprise, fear, sadness, anger, and disgust. Building upon this taxonomy, Luo and his team added “praise” as a new

category to capture emotions such as respect, trust, praise, liking, and well-wishes. Customizing Luo’s (2014) coding scheme, we developed our codebook to identify emotions in _HQSB_’s

coverage of the pandemic. The first author and second authors each coded 40 articles, yielding an intercoder reliability coefficient of 85%. The second author then continued to code the

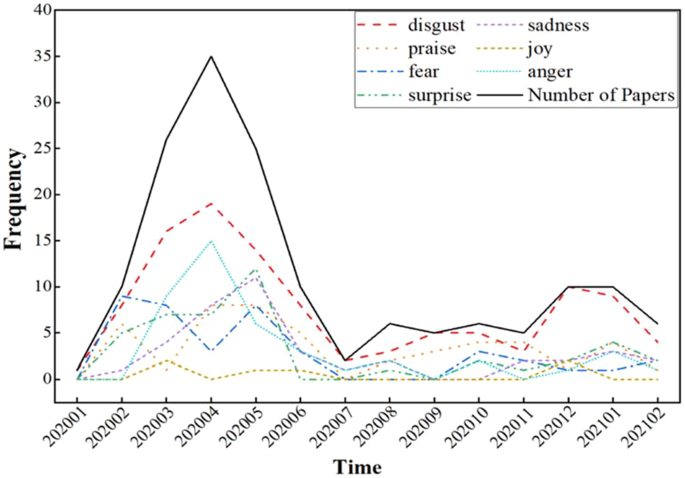

remainder of the dataset, leading to the identification of a total of 325 occurrences of emotions. We created a table describing the frequency of the seven emotions and a figure depicting

their temporal distribution to provide an overview of emotions in our dataset; these will be presented in the next section. Discourse analysis enables us to uncover implicit implications,

connections, strategies, and underlying rules or principles in media messages (van Dijk, 1983). To further unpack _HQSB_’s emotion mobilization strategies, we conducted a discourse analysis

of the coded extracts. We thoroughly examined the extracts coded with emotions and aimed to identify _HQSB_’s strategies in using emotions to advance its nationalistic agenda. After several

rounds of discussions, we identified six main emotion management strategies, one for joy and praise and one for each of the other five emotions. These strategies are driven by two

nationalistic narratives. To present our qualitative findings, we selected representative extracts from each strategy and translated them from Chinese into English. FINDINGS THE TEMPORAL

DISTRIBUTION OF VARIOUS EMOTIONS An examination of the overall frequency of emotions in our dataset reveals that the emotional tone of _HQSB_’s WeChat posts leans towards negative valence.

Among all observed emotions, “disgust” is the most frequent, appearing in nearly half (47%) of _HQSB_’s WeChat posts, while positive emotions such as “praise” and “joy” only appear in 25 and

4% of the articles, respectively. Other negative emotions, including “sadness,” “surprise,” and “anger,” each occur in approximately a quarter of the articles (see Table 1). It is worth

noting that the term “surprise” is used to express both positive and negative emotions. Therefore, it is evident that negative emotions dominate the e _HQSB_’s emotional management

strategies of during the early period of the Covid-19 pandemic. In terms of temporal distribution, we observed that the number of _HQSB_ posts on Covid-19 peaked in April and then sharply

declined before experiencing a resurgence in December 2020. This fluctuation corresponds to the fluctuation in the number of deaths due to Covid-19 in the United States, suggesting that

_HQSB_’s coverage of the pandemic may potentially be influenced by the coronavirus situation in the US (see Figs. 1 and 2). Generally, the overall distribution of emotions aligns with that

in the number of _HQSB_’s posts, especially for the most powerful emotions, such as “disgust” and “anger.” The peak of fear occurred earlier in February when coronavirus outbreaks emerged in

China. The emotion of fear resurfaced in April and May, triggered by the denial, mismanagement, and politicization of Covid-19 by Donald Trump’s administration, which led to global panic

and anxiety, resulting in an increase in sadness and surprise. The temporal pattern of the “praise” emotion follows a similar trend to that of “fear,” reflecting the complimentary comments

about the Chinese government’s handling of the pandemic. The analysis of temporal distribution suggests that pandemic containment events in both China and the US may shape the fluctuations

in _HQSB_’s coverage of Covid-19. DEFENSIVE NATIONALISM AND AGGRESSIVE NATIONALISM In the previous section, we provided an overview of emotion distribution in our dataset. In this section,

we delve deeper into the texts where emotions underpin different nationalistic narratives. We identified two types of nationalistic narratives employed in _HQSB_’s emotion management:

defensive nationalism and aggressive nationalism. Defensive nationalism, as defined by Rabinowitz (2022: 148–149), refers to a movement that prioritizes the nation-state and perceives

international forces as hostile, aiming to preserve and protect an existing nation-state. In the Chinese context, defensive nationalism represents a reactive rejection of external criticisms

rooted in a historical sense of insecurity (Shambaugh, 1996). Specifically, the defensive nationalistic narratives in _HQSB_’s coverage of Covid-19 reflect the mediated narratives projected

by _HQSB_ to justify the Chinese government’s virus containment measures and counter internal and external suspicions. Aggressive nationalism, on the other hand, entails a more assertive

expression of nationalistic sentiment through discursively attacking foreign others. According to Whiting’s (1983) elaboration, aggressive nationalism is mainly expressed through strident

anti-American speech and denunciations of foreign policies. In the context of Covid-19, aggressive nationalism manifests as an active critique of foreign countries for their mismanagement of

the virus, unfair judgment of China, and irresponsible vaccine distribution. Fundamentally, the aggressive nationalism in the context of Covid-19 arises from a sense of superiority due to

China’s achievements in virus containment (de Kloet et al., 2020). DEFENSIVE NATIONALISM: REBUILDING CONFIDENCE FOR THE STATE AND SYSTEM TRANSFERRING FEAR INTO SOLIDARITY Fear emerges

prominently during times of crisis, such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, and serves as the primary emotional drive underlying defensive nationalism. As depicted in Fig. 1, fear was the

prevailing emotional response during the initial stage of the outbreak in January. This reaction is not surprising, as scientific research has established that fear, stress, and anxiety are

the most common emotions experienced by the public during the initial phase of a pandemic (Herbert et al., 2021). _HQSB_’s extensive coverage of Covid-19, which highlights expressions of

fear towards China and its containment measures from actors in France, the United States, Australia, Iran, and among Chinese citizens themselves, demonstrates the significant role China

plays in the global landscape of fear. The salient aspect of _HQSB_’s approach lies in its handling of the emotion of fear. _HQSB_ endeavors to contain, transfer, neutralize, and ultimately

dispel public distrust while simultaneously fostering global support for China. To illustrate, in an article published on February 4th, 2020, Hu Xijin, the then-editor-in-chief of _HQSB_,

sought to assuage public apprehension by cultivating an environment of trust. > We must trust science and NOT JUST PANIC……We have to believe > that such a large-scale social

mobilization can block most of the > transmission channels of the new coronavirus but also quickly > discover most of the emerging clusters of transmission points. > Therefore, we

have BUILT A STRONG DEFENSE NETWORK against this > INVISIBLE ENEMY… After we have formed a strict national prevention > and control DEPLOYMENT, the future is already highly certain;

that > is, we will first contain the surging spread of the epidemic, turn > it from completely uncontrollable to controllable, and then step by > step, SURROUND AND ANNIHILATE it.

(Huanqiu shibao, 2020a) At the time of the article’s publication, Chinese citizens were grappling with a dual sense of anxiety stemming from the coronavirus outbreak. They faced the fear of

mortality from the contagion as well as apprehension surrounding restricted personal freedoms and economic stability. To alleviate this two-fold fear, Hu, the editor and commentator at

_HQSB_, advocated for the cultivation of “trust” as a counterbalance to “panic”. The author urged the public to have faith in strict social control measures such as mandatory quarantine,

social distancing, and contact-tracing systems, which he deemed essential and effective in establishing a “strong defense network” against the “invisible enemy”—the coronavirus. To further

strengthen the enemization of the virus, the author compared the elimination of the virus to a battle of “surrounding and annihilating” the “enemy”. By promising to turn “uncontrollable” to

“controllable”, the article legitimized the aggressive biopolitical control measures imposed by the CCP government by satisfying the public psychological need for immediate security and

promising prospects (Renström and Bäck, 2021). _HQSB_ utilized the war metaphor to establish a hierarchical power dynamic between the government and the public, positioning the government as

a dominant character responsible for protecting the passive and reliant ordinary populace. The use of first-person plural pronouns, such as “we,” fostered a sense of solidarity between the

author and the audience, enhancing the persuasive efficacy of the discourse (Kinsman et al., 2010). This analysis aligns with de Kloet’s (2021: 375) findings that panic, anxiety, and fear

reinforced support for restrictive policies, such as lockdowns, home quarantines, and mask mandates, during the Covid-19 pandemic. _HQSB_’s emotional management capitalizes on the sense of

security associated with dominant power relations to justify the Chinese government’s controversial measures. MOBILIZATION OF JOY AND PRAISE: CULTIVATING NATIONALISTIC PRIDE WITH EXTERNAL

APPLAUSE In the official narrative of _HQSB_, positive emotions such as joy and praise play a significant role in promoting nationalism among the Chinese audience. Chinese people’s joy,

particularly towards the successful containment of the virus at the end of 2020, is extensively depicted in _HQSB_’s articles, reinforcing the success of the government’s measures. For

instance, an article published on December 31st, _HQSB_ refutes the _New York Times_’s suggestion to “blame China for the spread of the pandemic”, using the first sentence to contest this

perspective. Instead, the success of China’s containment measures is emphasized, celebrating rather than critiquing China’s response to the pandemic. The article elicits feelings of joy and

happiness as a means to promote Chinese nationalism, asserting Chinese success in controlling the epidemic and evoking a sense of superiority over other countries. _HQSB_’s discourse

cultivates a competitive self-complacency among Chinese people, foregrounding China’s national achievement against Covid-19 and creating a clear division from other nations, particularly

those in the west. However, it is crucial to note that “the west” as used in this context does not always correspond with the geographic or political west, and particularly, it does not

equate to the United States. This ambiguity becomes apparent when we consider the “external applause” from nations such as Serbia. Traditionally, these countries would be considered part of

‘the west’, yet in _HQSB_’s narrative, they align more closely with ‘us’—they applaud and support China’s measures. This perceived contradiction highlights the flexible nature of these

labels in the propagandistic discourse. For example, Serbia and its president Aleksandar Vučić are depicted as model admirers of China, with their appreciation and compliments serving to

validate China’s actions and bolster its image on the global stage (see Fig. 3). It is important to acknowledge that this portrayal does not diminish the distinction between China and the

West in general, particularly the United States, which remains the primary ‘other’ in the larger narrative. In summary, this section suggests that _HQSB_ employs a multifaceted approach in

its emotional management, strategically evoking joy and praise to fuel both defensive and aggressive forms of nationalism. However, these strategies are deployed within a complex

geopolitical landscape, where the lines between ‘us’ and ‘other’ are continually negotiated and redefined. For instance, on January 16th, 2021, Vučić was quoted as saying “We came here to

welcome the airplane, not because of the vaccine quality, but to express the true friendship between China and Serbia. We truly appreciate China’s support to Serbia” (Huanqiu Shibao, 2021a).

The _HQSB_’s citation of Vučić and visual representation of the Serbian president’s respectful diplomatic gesture towards the Chinese vaccine adds to the notion of China as a benign great

power willing to shoulder global responsibility, with its technological advancement and generousity (Smith and Fallon, 2020). Further, _HQSB_ leveraged Serbia’s gratitude to China to

denounce the West, stressing that “Serbia’s approach is gaining support from other countries in the region which have had confidence in the vaccine distribution plan deployed by the EU”

(Huanqiu Shibao, 2021b). By employing a “horse-racing” analogy between China and Europe, _HQSB_ highlighted China’s strength and morality at the expense of the Europe’s reputation. Another

example that backed this generous/selfish great power dichotomy can be found in an article published on February 3rd, 2021. In this article, _HQSB_ referred to a news report by _The

Financial Times_ to illustrate this point. According to the report, after being turned away by European countries, some countries in the Balkan Peninsula that have been dedicated to joining

the EU have now turned to the East. Among them, Serbia which has received China’s Sinopharm Covid-19 vaccine and Russia’s Sputnik-V vaccine, has now become ‘the vaccination champion’ in

Europe. (Huanqiu Shibao, 2021b). In the same _Financial Times_ report being cited, a North Macedonian official expressed his government’s disappointment towards the EU’s delayed delivery of

vaccines. He stressed that his government only expected to receive vaccines from the EU as a means of demonstrating their allegiance to the Western community. However, the EU’s response was

delayed without a reasonable explanation, which left North Macedonian citizens feeling disheartened. _HQSB_ used a Western media report to contrast China’s efficient provision of urgent

medical supplies with the EU’s failure to do so. _HQSB_’s portrayal of China as a responsible and resourceful power that can fill the void of global public goods, while also being an

authoritarian state with strong resource mobilization capacity, sought to defend China’s image in the face of criticism (Zhao, 2021). Through the use of emotional praise and comparison,

_HQSB_ aimed to cultivate aggressive nationalistic sentiments in its readers, which will be further explored in the following section. AGGRESSIVE NATIONALISM: OTHERING THE US AS A TOOL OF

SOLIDARITY BUILDING If the emotions in the previous section legitimize Chinese virus containment measures, then disgust, anger, surprise and sadness are the main emotional registers _HQSB_

drew on to develop an aggressive nationalism. This form of nationalism operates by constructing an imagined enemy, typically the United States and other nations, as a means of generating

solidarity between the government and its citizens. Through the process of “othering” and attacking the perceived enemy, external criticism of Chinese virus containment measures is

effectively neutralized. This approach thus serves to bolster the government’s standing among the Chinese populace and reinforces nationalistic sentiments. THE POLITICS OF DISGUST:

CULTIVATING IMMUNITY AGAINST EXTERNAL CRITICISM Chinese propaganda does not solely consist of favorable coverage in China-related news. Our research reveals that the _HQSB_ has refined its

affective tactics to adopt a “reveal-and-attack” approach. Notably, _HQSB_ confronts international censure towards China without hesitation. Our data shows that China is predominantly

associated with the sentiment of disgust. _HQSB_ strategically cherry-picks negative remarks from reputable Western newspapers and crafts rebuttals to challenge such criticisms. This tactic

resembles a propaganda technique known as inoculation, as it seeks to preemptively refute potential objections (Compton et al., 2016; McGuire, 1961, 1964). Inoculation seeks to foster

attitudinal immunity to specific perspectives by presenting the audience with weakened arguments accompanied by preemptive rebuttals and encouragement to develop voluntary resistance against

future attitudinal attacks. One article entitled “Helping the country to pass through the US is the common mission for all the patriots today” cites American politicians’ censures of China

without specifying their specific criticisms: > From Secretary of State Pompeo to National Security Advisor > O’Brien to Republican senators like Cotton, it can be said that > they

take turns to scold China. They scold China on almost > everything, from accusing China of “trying to destroy the US > economy” to China’s “ulterior motives” in assisting Africa, >

to China’s use of Huawei to “monitor the world.” So, where did > their hatred of China come from ? (Huanqiu Shibao, 2020e) This carefully curated presentation serves to introduce Chinese

audiences to American politicians’ criticism of China without damaging the reputation of the CCP. However, the specific arguments made by American politicians are concealed, thus allowing

the criticisms to be delivered without inviting critical evaluation. Additionally, by using the term “scold” (骂), the criticisms are delegitimized and portrayed as expressions of unfounded

anger and hostility. This positioning suggests that these criticisms do not merit thoughtful consideration. The author employed geopolitical reasoning to interpret the United States’

“emotionalized scolding” of China. He asserted that the United States is stifling China in an effort to disrupt break up the aggregated interests of 1.4 billion Chinese people (Huanqiu

Shibao, 2020e). By presenting the viewpoint, _HQSB_ insinuates that American criticism is not anchored in rational foreign policy debates but is instead an calculated assault against China,

undermining both the interests of Chinese people and its government. To counterbalance international criticisms targeting Chinese governmental policies, the author appeals to all patriot

readers to understand that the essence of contemporary patriotism is to safeguard the national interests and the rights to improve their quality of life. THE POLITICS OF ANGER: THE US

AGAINST THE US Throughout the pandemic, the emotion of anger has been utilized as a fundamental framework to depict the US as a disappointing and corrupt political entity. Our research

demonstrates that, although China provokes and manifests anger towards numerous countries, the United States is the primary target of this emotion, with a considerable amount of anger

originating from within American society itself. Notably, our data capture expressions of fury from netizens directed towards American elites, who were ridiculed and criticized for their

negative assessments of China. For example, on March 10th, 2020, _HQSB_ referenced Republican Congressman Kevin McCarthy’s tweets, in which he referred to Covid-19 as the “Chinese

coronavirus” (as illustrated in Fig. 4). Rather than directly accusing McCarthy of racism, _HQSB_ deftly emphasized the escalating anger amongst American citizens, including those of Chinese

American descent. By incorporating the views of both a Chinese American and an Anglophone netizen (as shown in Fig. 5), _HQSB_ aimed to demonstrate the widespread frustration towards the

perceived racist rhetoric of American politicians. This strategy enabled _HQSB_ to depict a divided image of the United States, consisting of a group of corrupt and xenophobic politicians

attempting to manipulate the virus for geopolitical gain, and a community of ordinary Americans who stood in solidarity with the Chinese people against their morally bankrupt elites. Despite

the prohibition of social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter in mainland China, _HQSB_ actively utilized these platforms to engage with international sources, thus effectively

fostering a one-way connection between Chinese readers and overseas netizens, and conjuring an illusionary international digital public sphere beyond China’s Great Firewall. This revelation

discloses yet another mechanism for Chinese government to adapt internet censorship to reinforce authoritarian resilience (Han, 2023; King et al., 2013). By selectively engaging with and

presenting the crucial civic discussions from Western social media platform, _HQSB_ creates an imagined “we” that binds Chinese people with American populace, positioning the American elites

as the despicable “other”. Moreover, _HQSB_ capitalized on feelings of anger and superiority amongst Chinese readers towards the US government’s mishandling of Covid-19, lambasting their

incompetence and negligence. As exemplified in an article titled “The Modern Living Hell,” where the commentator expressed strong resentment towards federal officials’ failure to take urgent

measures at the national level: > If the Covid pandemic cannot be stopped, then America’s failure is > forgivable, but many Asian countries and economies including China > have

well contained the pandemic, which means that the pandemic can > be coped with. There is no point logically or morally, in > America’s surrender. (Huanqiu Shibao, 2020d) The above

excerpt illustrates that _HQSB_ endeavored to censure and denigrate the COVID-19 response of the United States by juxtaposing it with the efficacious pandemic containment measures

implemented by China and other Asian nations. SURPRISE: DEMYSTIFYING THE AMERICAN DREAM Within our entire corpus, the emotion of surprise constitutes a unique category that encapsulates both

positive and negative affective states. When surprise triggers negative emotions, _HQSB_ exploits this affective response to dismantle the myth of the American dream and to disabuse broader

perception of the West. Various sources, including China, the international community, and its own citizens, directed surprise emotions tinged with negative sentiment towards the United

States. On May 11th, 2020, _HQSB_ reported and analyzed an article published by _The Atlantic. HQSB_ cited a paragraph of the article: > When the virus arrived, it found a nation plagued

with significant > underlying conditions, which it exploited mercilessly. Long-standing > issues—a corrupt political class, a lethargic bureaucracy, a > merciless economy, a divided

and distracted populace—had been > neglected for years. We had become accustomed to living with these > discomforting symptoms. It required the vastness and immediacy of a >

pandemic to reveal their severity—to jolt Americans into realizing > that we are in the high-risk category. (Huanqiu Shibao, 2020d) _HQSB_ emphasized that the Covid-19 pandemic unveiled

deep-seated issues within American society, portraying it as a political structure beleaguered by corrupt elites, a stagnated bureaucracy, a floundering economy, and societal disarray. By

underscoring the shock and surprise experienced by Americans, the author shatters the illusion of a prosperous American society, which is often depicted as a bastion of democracy with a

sturdy economy and a harmonious citizenry. This emotional reaction illuminates the disparity between the idealized American Dream and the tangible economic, political, and social issues

within the nation. Contrary to authoritarian states that permit only a single dominant ideology, democratic states, including the US, tolerate dissenting and critical perspectives on social

issues. As a form of state-funded propaganda, _HQSB_ capitalizes on the plurality inherent to democratic states and employs critical commentary within American society to dissuade

idolization of the US among the Chinese populace. By highlighting the startling insecurity among the American people, HQSB strives to instill a sense of assurance and contentment among the

Chinese audience with regard to China as a state and the socialist system imbued with Chinese characteristics. The party-state’s fusion between socialism and nationalism that has taken shape

in the Jiang Zemin’s era has continued to exert ideological power under Xi’s governance as the socialist system under CCP’s rule has become an integral part of nationalism in China (Guo,

2003). When the emotion of surprise manifests positively, China has been noted to be a primary beneficiary of this sentiment, particularly from the global community and Russia. For instance,

an article published by HQSB on February 7, 2020, referenced a statement by a member of the WHO scientific team, lauding China’s commendable transparency during their on-site visit. The WHO

scientist noted that “The Chinese side responded to their requests during their personnel visit, demonstrating a surprising level of openness.” (Huanqiu Shibao, 2021c) In response to

international criticism accusing China of impeding the global investigation into the virus’s origin, _HQSB_ leveraged the testimony of the WHO scientist to affirm the Chinese government’s

transparency. The palpable surprise among foreign observers suggests a deep-rooted bias against the Chinese system, where the Western media’s stereotypical depiction of China stands in stark

contrast with the reality. Moreover, these surprising reactions support the contention that the investigation of the virus’s origin has been politicized on an international scale. Utilizing

the credibility of scientific experts, _HQSB_ has crafted two contrasting national images. One image casts China as a victim, unjustly vilified and shamed by the West for political purposes

relating to the global pandemic, while the other presents China as a competent nation with a transparent and efficient system that outperforms its Western counterparts. In this context, the

positive emotional reaction of surprise serves to cultivate national pride among the Chinese population, reinforcing their faith in China’s virus containment strategies and socialist

political system. THE POLITICS OF SADNESS (PARTICULARLY DISAPPOINTMENT): IMAGINING A DECLINING US LEADERSHIP The emotion of sadness functions in parallel with, and bolsters, the process of

demystifying Western society. Within the broader family of “sadness” emotions, disappointment serves as the primary sentiment harnessed by Western countries to reveal inherent societal

fractures. For instance, according to an _HQSB_ report, the Premier of Ontario, Canada, expressed profound disappointment in the United States due to the Trump administration’s decision to

halt the exportation of protective masks to Canada by medical equipment manufacturer 3 M. In his statement, Ford remarked “there are no other countries as close as the United States and

Canada… I am truly disappointed that the US suddenly suspends the mask supply to Canada… and I think the political trick is unacceptable.” This highlights how disappointment functions as a

mechanism to expose the deficiencies and divisions within the Western community (Huanqiu Shibao, 2020c) _HQSB_ utilizes Ford’s public display of disappointment as a means to discredit

America’s reputation as a reliable partner in international cooperation. By fully displaying Canada’s disappointment, _HQSB_ effectively delegitimizes American political leadership, casting

the US as an egoistic hegemon that lacks compassion for its closest ally and reneges on its commitment to supply public goods during the global pandemic. Through this method, _HQSB_ aims to

reduce America’s global clout and undermine its capacity to forge and sustain partnerships with other nations. By emphasizing Canada’s disappointment, _HQSB_ highlights the perceived lack of

cooperation and solidarity from the US, thereby reduce America’s global clout. This approach effectively contests the US’s moral authority and impairs its reputation as a reliable ally,

which could potentially result in adverse implications for its relationships with other countries. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION The COVID-19 pandemic was a period during which the Chinese

government exhibited significant authoritarian resilience, managing to transform public mistrust, grievances, and anger into confidence, solidarity, and even complacency. Our research

contends that the emotion management strategies of the CCP are strategically intertwined with nationalistic discourses. We discovered that _HQSB_’s emotional management is underpinned by a

binary construction of a “despicable them” and an “innocent us,” with the former being represented by the US and the latter being China and its citizens. This dichotomy echoes the Sino-US

geopolitical confrontation and represents strategic othering for nation-building purposes. Our research indicates that _HQSB_’s emotional management is primarily structured by two

nationalistic discourses: defensive nationalism and aggressive nationalism. Defensive nationalism seeks to contain public fear and anxiety by fostering a sense of solidarity between the

people and the government (“us”) against the pandemic virus (“them”). This strategic othering of the virus exploits the fear surrounding it. Chinese nationalistic media distract the public

from the government’s systemic dysfunction at the initial stage of the pandemic and direct attention toward combating a threatening “other,” i.e., the COVID-19 virus. This approach resonates

with Zhang’s (2022) findings about China’s disaster nationalism during the pandemic, intended to engender compliant publics submissive to government control and cooperative with stringent

containment measures. This defensive nationalism operates as a variant of the “positive energy” promotion inherent in Chinese propaganda during public health crises, only seasoned with

HQSB’s unique jingoistic war metaphors to justify extreme governmental measures. Another pillar of _HQSB_’s defensive nationalism is construed with the emotions of praise and joy. In line

with other official propaganda such as _People’s Daily_, _Xinhua News_, and _China Daily_, we found that _HQSB_ conveys a sense of globalism that championed building a “community with a

shared future for humanity” (Yang and Chen, 2021). The only difference rests in _HQSB_’s highlight of foreign voices. Specifically, HQSB appropriates international admiration and gratitude

from friendly governments, such as Serbian President Vučić, to bolster political confidence in virus containment measures, the authoritarian rule, and the socialist system with Chinese

characteristics. Aggressive nationalism, compared to defensive nationalism, is a more pronounced tool in HQSB’s emotional management campaign, accomplished via strategic othering. By

selectively showcasing critical comments from Western politicians, _HQSB_ reframes external criticisms against the Chinese political system as concerted hostility driven by geopolitical

calculations. The “disgust” emotion projected by Western powers is thus reinterpreted as a strategic containment against China that recalls the collective memory of the “century of

humiliation” and calls for collective resistance from the Chinese population (Yu, 2022). As a news outlet dedicated to international news reporting, _HQSB_ uses emotions such as anger,

surprise, and disappointment from within Western society to demystify the United States as a model of liberal democracy and a responsible global leader. By tapping into the populist

sentiment within Western society characterized by anti-elitism and anti-establishment sentiments (Hameleers, 2019; Homolar and Löfflmann, 2021), the party media exposes the internal

divisions and malfunctions of Western democracies during crises, in turn boosting the legitimacy of the CCP’s authoritarian rule. This paper not only explores the intricacies of Chinese

propaganda’s emotional management mechanisms but also illuminates how these mechanisms are deployed in line with China’s geopolitical objectives and in response to its international

relations, particularly those with the United States. This contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of how international news, especially that pertaining to the US, is converted

into domestically relevant propagandistic content in China. The article also furthers the literature on affective governance strategies within Chinese official propaganda during the

pandemic, particularly on social media platforms. Future research could delve into the effects of the Chinese government’s emotional mobilization during Covid-19 and subsequent public health

crises. DATA AVAILABILITY The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WOHWYD. These datasets were derived from the

following public domain resources: https://www.huanqiu.com/. CHANGE HISTORY * _ 10 NOVEMBER 2023 A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02315-4 _

REFERENCES * Callahan W (2004) National insecurities: humiliation, salvation, and Chinese nationalism. Altern Glob Local Polit 29(2):199–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540402900204

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Chen X, Kaye D, Zeng J (2021) #Positive energy douyin: constructing “playful patriotism” in a Chinese short-video application. Chin J Commun

14(1):97–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2020.1761848 Article Google Scholar * Chen Z, Wang C (2019) The discipline of happiness: the foucauldian use of the “positive energy”

discourse in China’s ideological works. J Curr Chin Aff 48(2):201–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1868102619899409 Article Google Scholar * Compton J, Jackson B, Dimmock J (2016) Persuading

others to avoid persuasion: inoculation theory and resistant health attitudes. Front Psychol 7:122. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00122 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* de Kloet J, Lin J, Chow Y (2020) ‘We are doing better’: biopolitical nationalism and the COVID-19 virus in East Asia. Eur J Cult Stud 23(4):635–640.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549420928092 Article Google Scholar * de Kloet J, Lin J, Hu J (2021) The politics of emotion during COVID-19: turning fear into pride in China’s WeChat

discourse. Chin Inf 35(3):366–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X211048290 Article Google Scholar * Ekman P (1992) Are there basic emotions? Psychol Rev 99(3):550–553.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.3.550 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gao P, Wu Y (2019) From agenda setting to emotion setting: emotion guidance of people’s daily during

China-US trade disputes. Chin J Mod Commun 10:67–7 Google Scholar * Greene SA, Robertson G (2020) Affect and autocracy: emotions and attitudes in russia after crimea. Perspect Polit

20(1):38–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720002339 Article Google Scholar * Gries PH (2004) China’s new nationalism: pride, politics, and diplomacy. University of California Press,

Oakland Google Scholar * Guan T, Hu T (2020) The conformation and negotiation of nationalism in China’s political animations—a case study of Year Hare Affair. Continuum 34(3):417–430.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2020.1724882 Article Google Scholar * Guo Y (2003) Cultural Nationalism in contemporary China: the search for National Identity under Reform, 1st edition.

Routledge, London Google Scholar * Hameleers M (2019) The populism of online communities: constructing the boundary between “blameless” people and “culpable” others. Commun Cult Crit

12(1):147–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz009 Article Google Scholar * Han R (2023) Debating China beyond the great firewall: digital disenchantment and authoritarian resilience. J

Chin Polit Sci 12(1):147–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz009 Article Google Scholar * Hatef A, Luqiu LR (2018) Where does Afghanistan fit in China’s grand project? A content analysis

of Afghan and Chinese news coverage of the One Belt, One Road initiative. Int Commun Gaz 80(6):551–569 Article Google Scholar * Herbert C, El Bolock A, Abdennadher S (2021) How do you feel

during the COVID-19 pandemic? A survey using psychological and linguistic self-report measures, and machine learning to investigate mental health, subjective experience, personality, and

behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic among university students. BMC Psychol 9(1):90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00574-x Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hird D

(2018) Smile yourself happy: Zheng Nengliang and the discursive construction of happy subjects. In: Wielander G, Hird D (eds.) Chinese discourses on happiness. Hong Kong University Press,

Hong Kong, pp. 106–128 Google Scholar * Homolar A, Löfflmann G (2021) Populism and the affective politics of humiliation narratives. Glob Stud Q 1(2):1–2.

https://doi.org/10.1093/isagsq/ksab002 Article Google Scholar * Huang H (2015) Propaganda as signaling. Comp Polit 47(4):419–444. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041515816103220 Article Google

Scholar * Huang H (2018) The pathology of hard propaganda. J Polit. https://doi.org/10.1086/6968 * Huanqiu Shibao (2020a) A reminder to a few countries: don’t think that China is going to

collapse this time, and think it’s okay to hit China when it is down. Huanqiu Shibao. Retrieved from https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/d9iYtcDVqEtYQYZiL3MekQ * Huanqiu Shibao (2020b) A high-ranking

US Congress official used the ‘Chinese virus’ in a post, which was scolded by US netizens. Huanqiu Shibao. Retrieved from https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/txnPzXPMVNTuOfqGDzOHmQ * Huanqiu Shibao

(2020c) ‘We have such a good relationship, but the United States suddenly played such a trick, which is unacceptable’. Huanqiu Shibao. Retrieved from

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/apnBjgz-XuXWGKs8e_RMUQ * Huanqiu Shibao (2020d) This article from US media goes deep: we live in a failed country. Huanqiu Shibao. Retrieved from

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/VDj1W9zQ-J7EzH5PgJwqDw * Huanqiu Shibao (2020e) Hu Xijin: it is the common mission of today’s patriots to help the country get through the hurdle of the United

States. Huanqiu Shibao. Retrieved from https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/tQ7AzhGGYX5UtDAmvyNe_Q * Huanqiu Shibao (2021a) China’s vaccine is coming, the president welcomes the plain in person.

Huanqiu Shibao. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/erCy4e9rXrsGTr99P0j_LA * Huanqiu Shibao (2021b) These disillusioned European countries turn to China and Russia. Huanqiu Shibao. Retrieved from

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/pBs5cduQ4nDYw7sNXFNiKg * Huanqiu Shibao (2021c) ‘China responds to every request’. Huanqiu Shibao. Retrieved from https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Y9rwYQgp_WMnCFqEwSVQKQ

* Jacob J (2020) ‘To Tell China’s Story Well’: China’s international messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Rep 56(3):374–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009445520930395 Article

Google Scholar * Jaworsky B, Qiao R (2021) The politics of blaming: the narrative battle between China and the US over COVID-19. J Chin Polit Sci 26(2):295–315.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09690-8 Article PubMed Google Scholar * King G, Pan J, Roberts M (2013) How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective

expression. Am Polit Sci Rev 107(2):326–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055413000014 Article Google Scholar * Kinsman H, Roter D, Berkenblit G et al. (2010) “We’ll do this together”: the

role of the first person plural in fostering partnership in patient-physician relationships. J Gen Intern Med 25(3):186–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1178-3 Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Larson C (2011) China’s fox news. Foreign Pol. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/10/31/chinas-fox-news/ * Lu Y, Pan J (2021) Capturing clicks: how the Chinese

government uses clickbait to compete for visibility. Polit Commun 38(1–2):23–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1765914 Article Google Scholar * Luo C, Ding W, Zhao W (2014) Factual

framework and emotional discourse: news frame and discourse analysis in editorial of global times and Hu xijin’s microblog. Chin J J Commun 36(8):38–55 Google Scholar * McGuire W (1961)

Resistance to persuasion conferred by active and passive prior refutation of the same and alternative counterarguments. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 63(2):326 Article Google Scholar * McGuire W

(1964) Some contemporary approaches. In: Berkowitz L (ed.) Advances in experimental social psychology, vol 1. Academic Press, New York, pp. 191–229 Chapter Google Scholar * Mylonas H,

Whalley N (2022) Pandemic nationalism. Natl Pap 50(1):3–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2021.105 Article Google Scholar * Newsrank (2022) Global times-xinbang public account’s detail.

Newsrank. https://newrank.cn/new/?account=hqsbwx * Perry E (2002) Moving the masses: emotion work in the Chinese revolution. Mobilization 7(2):111–128.

https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.7.2.70rg70l202524uw6 Article Google Scholar * Rabinowitz B (2022) Defensive nationalism: where populism meets nationalism. Nationalism Ethn Polit

28(2):143–164 Article Google Scholar * Renström E, Bäck H (2021) Emotions during the Covid-19 pandemic: fear, anxiety, and anger as mediators between threats and policy support and

political actions. J Appl Soc Psychol 51(8):861–877. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12806 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schneider F, Hwang Y (2014) The sichuan earthquake

and the heavenly mandate: legitimizing Chinese rule through disaster discourse. J Contemp China 23(88):636–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2013.861145 Article Google Scholar *

Shambaugh D (1996) Containment or engagement of China? Calculating Beijing’s responses. Int Security 21(2):180–209. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539074 Article Google Scholar * Shi W, Liu S

(2019) Pride as structure of feeling: Wolf Warrior II and the national subject of the Chinese dream. Chin J Commun 13(3):329–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2019.1635509 Article

Google Scholar * Smith N, Fallon T (2020) An epochal moment? The COVID-19 pandemic and China’s international order building. World Affairs 183(3):235–255.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0043820020945395 Article PubMed Central Google Scholar * Song L, Liu S (2022) Demobilising and reorienting online emotions: China’s emotional governance during the

COVID-19 outbreak. Asian Stud Rev 0(0):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2022.2098254 Article Google Scholar * Sorace C (2021) The Chinese Communist Party’s nervous system: affective

governance from Mao to Xi. China Q 248(S1):29–51. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741021000680 Article Google Scholar * Stancheva T (2021) 21 Mind-Blowing WeChat statistics you should know

in 2022. Review 42. https://review42.com/resources/wechat-statistics/ * Sullivan J, Wang W (2022) China’s “wolf warrior diplomacy”: the interaction of formal diplomacy and cyber-nationalism.

J Curr Chin Aff 52(1):68–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681026221079841 Article Google Scholar * van Dijk T (1983) Discourse analysis: its development and application to the structure of

news. J Commun 33(2):20–43 Article Google Scholar * Wang Z (2008) National humiliation, history education, and the politics of historical memory: patriotic education campaign in China. Int

Stud Quart 52(4):783–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2008.00526.x Article Google Scholar * Whiting A (1983) Assertive nationalism in Chinese foreign policy. Asian Surv

23(8):913–933 Article Google Scholar * Xie K, Zhou Y (2021) The cultural politics of national tragedies and personal sacrifice: state narratives of China’s ‘ordinary heroes’ of the

COVID-19 pandemic. Made Chin J 6(1):24–29. https://doi.org/10.22459/MIC.06.01.2021.02 Article Google Scholar * Xu B (2018) Commemorating a difficult disaster: naturalizing and

denaturalizing the 2008 Sichuan earthquake in China. Mem Stud 11(4):483–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698017693669 Article Google Scholar * Yang P, Tang L (2018) ‘Positive energy’:

hegemonic intervention and online media discourse in China’s Xi Jinping era. China Int J 16(1):1–22 Article Google Scholar * Yang Y, Chen X (2021) Globalism or nationalism? The paradox of

Chinese official discourse in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. J Chin Polit Sci 26(1):89–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09697-1 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Yu Y (2022)

Resisting foreign hostility in China’s english-language news media during the COVID-19 crisis. Asian Stud Rev 46(2):254–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2021.1947969 Article MathSciNet

Google Scholar * Zeng J (2014) The debate on regime legitimacy in China: bridging the wide gulf between Western and Chinese scholarship. J Contemp China 23(88):612–635.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2013.861141 Article Google Scholar * Zeng W, Sparks C (2020) Popular nationalism: global times and the US–China trade war. Int Commun Gaz 82(1):26–41.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048519880723 Article Google Scholar * Zhang C (2020) Covid-19 in China: from ‘Chernobyl Moment’ to impetus for nationalism. Made China J 5(2):162–165.

https://doi.org/10.22459/MIC.05.02.2020.19 Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhang C (2022) Contested disaster nationalism in the digital age: emotional registers and geopolitical imaginaries

in COVID-19 narratives on Chinese social media. Rev Int Stud 48(2):219–242. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210522000018 Article Google Scholar * Zhang C, Zhang D, Shao HL (2023) The

softening of Chinese digital propaganda: evidence from the People’s Daily Weibo account during the pandemic. Front Psychol https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1049671 * Zhang D, Jamali A

(2022) China’s “weaponized” vaccine: intertwining between international and domestic politics. East Asia J 39(3):279–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12140-021-09382-x Article Google Scholar

* Zhang D, Xu Y (2022) When nationalism encounters the COVID-19 pandemic: understanding Chinese nationalism from media use and media trust. Glob Soc 37(2):176–196.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2022.2098092 Article Google Scholar * Zhao S (1998) A State-Led nationalism: the patriotic education campaign in Post-Tiananmen China. Communis Post-Commun

31(3):287–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-067X(98)00009-9 Article Google Scholar * Zhao S (2021) Rhetoric and reality of China’s global leadership in the context of COVID-19:

implications for the US-led world order and liberal globalization. J Contemp China 30(128):233–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2020.1790900 Article Google Scholar * Zhou Y, Xie K

(2022) Gendering national sacrifices: the making of new heroines in China’s counter-COVID-19 TV series. Commun Cult Crit 15(3):372–392. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcac014 Article Google

Scholar * Zou S (2021) Restyling propaganda: popularized party press and the making of soft propaganda in China. Inform Commun Soc 26(1):201–217.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1942954 Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research is supported by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [Grant number:

2022M712941], “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities”, [Grant Number: CUC230B056], Asia Media Research Center, Communication University of China [Grant number:

AMRC2022-12]. We would like to acknowledge support from Yanyang Wei from Communication University of China. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * School of Government and Public

Affairs, Communication University of China, Beijing, China Chang Zhang * Department of Applied Linguistics & Student Opportunity, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK Zi Wang Authors *

Chang Zhang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Zi Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to CZ. Dr. ZW makes secondary contribution to the research conduct and article drafting. CORRESPONDING

AUTHOR Correspondence to Chang Zhang. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICAL APPROVAL This article does not contain any studies with

human participants performed by any of the authors. INFORMED CONSENT This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION APPENDIX RIGHTS AND

PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any

medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The

images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not

included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly

from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Zhang, C., Wang,

Z. Despicable ‘other’ and innocent ‘us’: emotion politics in the time of the pandemic. _Humanit Soc Sci Commun_ 10, 418 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01925-2 Download citation *

Received: 07 October 2022 * Accepted: 11 July 2023 * Published: 15 July 2023 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01925-2 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with

will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(341x524:343x526)/witney-carson-1-168e73b4df4d4696bf9a5f06bdda0708.jpg)