- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Intergenerational support from children and differences in social security treatment are important factors influencing the occurrence of multidimensional poverty among the elderly

in China. Drawing on social support theory, based on the data of the 2018 Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey, this article investigates the effects of different intergenerational

support provided by children on multidimensional poverty among the elderly, using a combination of logit regression model and moderating effect model, and identify the role played by social

security programs. The study shows that multidimensional poverty among the elderly in China is generally severe, and the structure of poverty is evolving from material to spiritual poverty.

The effectiveness of financial and caregiving support in the management of multidimensional poverty among the elderly has diminished and is limited to rights-based poverty, and the effects

are in opposite directions. Emotional support assumes an increasingly important role in poverty management and has a significant impact on the alleviation of economic, health, and spiritual

poverty as well as overall multidimensional poverty. Social security programmes have significant moderating effects on the relationship between financial support, emotional support and

multidimensional poverty among the elderly, and differences in social security programmes can cause changes in the impact of intergenerational support on multidimensional poverty among the

elderly. This study has theoretical value and practical implications for building a solid bottom line for a mass return to poverty and improving the current situation of multidimensional

poverty among the elderly in China. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS OF ADULT CHILDREN, INTERGENERATIONAL SUPPORT, AND THE WELL-BEING OF CHINESE OLDER ADULTS

Article Open access 05 August 2023 NON-CORESIDENTIAL INTERGENERATIONAL RELATIONS FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF ADULT CHILDREN IN CHINA: TYPOLOGY AND SOCIAL WELFARE IMPLICATIONS Article Open access

01 May 2024 DYNAMICS OF MULTIDIMENSIONAL POVERTY AND ITS DETERMINANTS AMONG THE MIDDLE-AGED AND OLDER ADULTS IN CHINA Article Open access 18 March 2023 INTRODUCTION In recent years, the

size of China’s aging population has been expanding (Bai & Lei, 2020). According to the data of the 7th National Population Census released by the National Bureau of Statistics of China

in 2020, the current population of China is 190.64 million people aged 65 years and older, accounting for 13.5% of the total population. Compared with the 6th national census in 2010, the

proportion of the population aged 65 and above has increased by 4.63%. with the proportion of the population aged 65 and above fast approaching 14%, China’s population structure will

transition from light to moderate aging in a very short period. In fact, except for Tibet, the proportion of the population aged 65 and above is over 7% in 30 other provinces in China, and

12 of them have already exceeded 14%, taking the lead in the stage of moderate aging. Meanwhile, China is entering the “post-poverty alleviation” era, as it won the battle against poverty in

2020, with the focus on poverty reduction shifting from absolute poverty to relative and multidimensional poverty (Deng et al., 2019; Zhong & Lin, 2020). Old age is the stage of the

life cycle with the highest incidence of poverty. Many older adults are more likely than others to fall into poverty and become a rapidly expanding group of the new poor due to their

declining work capacity and reduced or even lost labor income, making it difficult to sustain a daily living on retirement income alone (Wang et al., 2011). In addition to income poverty,

other dimensions of poverty, such as physical and mental health and life satisfaction, are also major challenges for older people. Therefore, older adults should be the focus of

multidimensional poverty governance under the background of rapid aging. According to the dominant Confucian culture in China, filial piety is considered one of the core values in Chinese

traditional culture. Filial ethics, such as “raising children is an insurance for old age” and “filial piety is one of the virtues to be held above all else”, have long been deeply rooted

among the people (Sun, 2017). As a culture highly valued in China, filial piety has a strong influence on motivating adult children to take care of their parents (Lai & Leonenko, 2007).

Furthermore, filial children are required, not only to provide materials but also to show reverence and respect. Some scholars have pointed out that, social support for most older adults is

from their children, who provide them with a sense of purpose in life, as well as emotional and economic support (Zhen & Silverstein, 2012). However, the population, economy, and family

status, are experiencing huge changes in China. Firstly, family miniaturization is becoming more and more serious. According to China’s seventh census in 2020, the average household size in

China is only 2.62 persons, down 0.48 persons from 3.10 persons in the sixth census in 2010, which is below the bottom line of the number of "three-person households". This

situation indicates that the pressure on Chinese children to support the elderly is increasing. Secondly, population mobility and household separation are becoming normalized, with 493

million people separated from households and 376 million people on the move in 2020. Compared with the sixth national census in 2010, the number of people separated from their families

increased by 125 million, or 88.52%; the number of mobile population increased by 154 million, or 69.73%. This situation shows that the reality of a large number of children going out to

work has led to a gradual increase in the number of elderly people left behind and empty nesters in China. The aging, fewer children and the increasing acceleration of the phenomenon of

youth mobility have led to a gradual change in the traditional Chinese culture of filial piety (Zhang, 2017). In this context, is raising children truly insurance for old age? Can the

intergenerational support provided by children to their parents impact the multidimensional poverty of older adults? What is the extent to which different types of intergenerational support

affect different dimensions of poverty among the elderly? Research on these questions is not only a practical necessity to consolidate China’s poverty eradication achievements and prevent a

return to poverty but also a historical necessity to enhance the development capacity of China’s elderly vulnerable groups and achieve the goal of common prosperity. The urgency of the

problem has led to a boom in research on multidimensional poverty in old age, but less research has been done to explore the impact of intergenerational support on multidimensional poverty

in old age at the level of filial piety. Specifically, the existing research on multidimensional poverty in old age has focused on three areas. First, the identification of multidimensional

poverty in old age and the selection of measurement indicators. The understanding of poverty in academia has experienced an evolution from a single dimension to multiple dimensions. In the

early stage, studies in the literature mainly identified and measured poverty in terms of a single economic dimension, such as income or consumption (Decerf, 2020). However, with the

continuous development of the economy, some scholars have pointed out that it is not appropriate to define poverty from the economic perspective, and that the single income dimension is

insufficient to measure poverty, and it cannot measure the complexity of poverty comprehensively and truly (Rowles & Johansson, 1993). Amartya Sen (1999) alleviated this problem by

proposing a multidimensional poverty theory, which pointed out that the essence of poverty is the deprivation of people’s basic feasible abilities. In addition to income poverty, it also

includes many objective aspects, such as health, education, housing and subjective feelings of welfare. This theory has deepened the knowledge and understanding of poverty, and has also been

supported by scholars, who believe that poverty is multidimensional (Atkinson, 2003; Von Maltzahn & Durrheim, 2008). Subsequently, the academic community has expanded the measurement of

poverty from single dimensions, such as income or consumption to multidimensional poverty dimensions. Some scholars emphasize the importance of individual development, subjective

perceptions, and quality of life, advocating the measurement of multidimensional poverty from non-monetary indicators such as education, health, and quality of life (Wicks-Lim & Arno,

2017; Pinilla-Roncancio, 2018). For example, Zhang and Zhou (2015) then analyzed the breadth, depth, and intensity of multidimensional poverty in China around the dimensions of education,

children’s living conditions, health, and public services. Some scholars emphasize the need to consider monetary and non-monetary indicators together and advocate a comprehensive measure of

multidimensional poverty in terms of income, education, and health dimensions (Guo & Zhou, 2016). For example, George and Bearon (1980) mentioned the need to measure the level of

well-being and poverty in old age in four dimensions: income, health status, life satisfaction, and self-esteem. Gorman and Heslop (2002) found in their study of old age poverty in Asian and

African developing countries that old age poverty is not only reflected in the income or consumption dimensions, but also in the family and social support, the health status and health

services. Based on this, the academic community has also constructed various multidimensional poverty measurements indices, such as the H-M index constructed by Hagenaars (1987), the Tsui

Poverty Composite Index constructed by Tsui (2002), the Participatory Poverty Index constructed by Li et al. (2005), and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in collaboration with

the Oxford Centre for Poverty and Human Development (OPHI) in the United Nations Human Development Report 2010, the Multidimensional Poverty Index, etc. (UNDP, 2010). Scientifically

measuring the poverty of older adults from multiple dimensions is conducive to achieving the goal of targeted poverty alleviation (Sun & Zhang, 2018). Therefore, as China’s poverty

alleviation work after 2020 improves to a new level, it is more scientific to discuss poverty among older adults from a multidimensional perspective. Second, the research on the measurement

of multidimensional poverty in the elderly. Since the measurement methods are somewhat universal, no specific measurement methods have been developed specifically for multidimensional

poverty among older individuals, and most of them are used in the research process following the universal measurement methods. In the discussion of multidimensional poverty measurement

methods, Amartya Sen believes that mathematical axiology is the core issue to be considered in multidimensional poverty measurement. Based on this, different scholars have developed various

measurement methods around mathematical axioms, among which the most representative ones are mainly two. One is the static multidimensional poverty measurement method, which is mainly used

for multidimensional poverty assessment at cross-sectional time points. Typical measures are the Watts Multidimensional Poverty Index and the A-F count measure proposed by Alkire and Foster

(2011). The implementation of this method has achieved the transformation of multidimensional poverty measurement from complex to simple (Wang, 2017). The second is the dynamic

multidimensional poverty measure developed mainly based on poverty decomposability, which advocates measuring multidimensional poverty from temporary poverty and long-term poverty. For

example, Foster (2007) developed a poverty line and duration parallel alignment for measuring the dynamics of poverty, but this income dimension-based approach cannot decompose poverty.

Therefore, based on it, Zhang et al. (2013) further introduced the experience time of poverty to overcome the problem that the dynamic poverty decomposition method is insensitive to the

length of time. The idea of developing different measurement methods provides a useful reference for the measurement of multidimensional poverty among the elderly. Third, the exploration of

factors influencing multidimensional poverty among the elderly. The current research on the factors affecting the poverty of older adults can be divided into three aspects. The first is the

personal level. Studies have pointed out that the gender, age, marital status, education level, and physical and psychological conditions of older adults are the main factors affecting the

occurrence of poverty in older adults (Jiao et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020). Secondly, from the perspective of the family, the income of the family and the number of children also have a

significant impact on older adults falling into poverty (Chen & Jordan, 2018; Guo, 2014). Finally, social factors will also affect the poverty of older adults. Some scholars believe that

the probability of falling into poverty differs between older adults living in rural areas and those living in cities and towns. The difference in geographic location of the eastern,

central and western regions will also cause older adults to fall into different poverty levels (Chen et al., 2020). In addition, whether older adults participate in social pension insurance

will also affect the probability of poverty (Cheng et al., 2018; Yang & Mukhopadhaya, 2018). At the micro level, studies that specifically explore the effects of intergenerational

support on multidimensional poverty among older adults are generally scarce and can be broadly classified into three categories. One is the theoretical interpretation of the mechanism of the

role of intergenerational support on multidimensional poverty in old age. For example, Yi (2018), based on the theoretical analysis of spatial poverty, institutional provision, and

capability poverty, clearly points out that intergenerational support from children can significantly suppress the incidence of poverty among the urban elderly population in China, but along

with the structural changes of Chinese urban families, especially the obvious decline in the number of children, the suppressive effect of intergenerational support on the incidence of

poverty among the urban elderly population in China is gradually declining. In addition, Krause (2001) also indicated that when the support provided by children fails to meet the needs of

older adults, it also leads to feelings of helplessness, disappointment and intergenerational tensions, which deteriorate their psychological health and reduce their life satisfaction. The

second is to explore the impact of different types of intergenerational support on a single dimension of multidimensional poverty in old age. For example, Yin and Zhou (2021) used a logit

regression model to investigate the pathways between financial support, spiritual comfort behaviors, life care behaviors, and health poverty of elderly living alone based on survey data of

2113 urban elderly living alone in Shanghai, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Dalian, and Hohhot. Zhang (2021) used a random effects logit model to explore the effects of two-way intergenerational

support on mental poverty among urban and rural elderly, and found that financial and instrumental support from offspring to relatives increased mental poverty among the elderly. Cong and

Silverstein (2008) indicated that intergenerational support could improve the mental state of the elderly and that emotional support among intergenerational support had a better effect than

financial and instrumental support. Third, the impact of a dimension or a characteristic in intergenerational support on different types of multidimensional poverty in old age is explored.

For example, Yu et al. (2019) analyzed rural elderly poverty from two perspectives: income poverty and spiritual poverty, and found that the quality of intergenerational relationships with

children had a significant effect on rural elderly poverty. Using the Probit model, Liu (2018) pointed out that the strength of intergenerational economic support is an important factor

influencing subjective poverty, consumption poverty and income poverty in old age. Based on survey data of low-income older adults in Northeast, East, South and Central China, Ci and Ning

(2018) used OLS regression with a binary logit model to find that intergenerational family support significantly improved the economic status and health status of the poor older adults, but

did not significantly enhance the life satisfaction of the poor older adults. In view of the past, existing studies have laid an important foundation for cognizing the current situation,

measurement, and influencing factors of multidimensional poverty among the elderly, expanding research horizons, and inspiring research ideas. However, there are still obvious shortcomings

in the existing studies: (1) In the context of the decline of traditional filial culture, the degree of concern about the relationship between intergenerational support and multidimensional

poverty in old age is far from adequate, and not many scholars have conducted research on it. (2) In terms of research content, most of them follow the "many-to-one" and

"one-to-many" research ideas, and there is a lack of detailed research exploring the impact of different types of intergenerational support on different types of multidimensional

poverty. (3) There is room for improvement in the existing research literature in terms of research methodology. Most of the existing studies have adopted traditional research methods such

as theoretical discussions and empirical analyses, as well as localized regional studies using a single statistical method, and lack quantitative analyses based on a large national sample.

(4) Ignoring the objective fact that social security mechanisms play a role in the relationship between intergenerational support for children and multidimensional poverty in old age. Based

on this, to respond to the practical needs of multidimensional poverty governance in old age in the practical dimension and echo the in-depth investigation of the relationship between

intergenerational support and multidimensional poverty in old age in the theoretical dimension. Based on the data from the 2018 Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), this

study attempts to use various quantitative statistical analysis methods, such as the logit regression model and moderating effect model to further explore the effects of financial support,

emotional support and care support provided by children on the overall multidimensional poverty of the elderly, and further distinguish the effects of three kinds of intergenerational

support on the economic poverty, health poverty, spiritual poverty and rights poverty of the elderly. Social security mechanisms are also included in the study of the effects of

intergenerational support on multidimensional poverty in old age to enrich the study of multidimensional poverty in old age in multiple dimensions. THEORY AND RESEARCH HYPOTHESES Based on

the capability theory and the process of poverty developing from single dimensions to multiple dimensions, most scholars now include physical, mental and economic conditions in the

measurement of multidimensional poverty. Amartya Sen (1999) has pointed out that poverty must be seen as the deprivation of basic human capabilities and rights rather than merely as the

lowness of income. Therefore, this paper includes rights poverty with economic, health and spiritual poverty, to measure the multidimensional poverty of older adults. In social support

theory, social support refers to a selective social behavior of using material and spiritual means such as information, legal, financial and psychological resources to help socially weak

people without compensation. Social support behavior has a unique main effect function (gaining health care) and buffer function (buffering and reducing pressure), which is conducive to

helping individuals cope with various social risks and relieving their physical, psychological and social stress. Family is a basic unit of life with high internal cohesion based on blood

and emotion and is the main carrier of the elderly’s daily life. Therefore, in the framework of social support for the elderly in China today, the family becomes the basic subject of the

elderly care business. As the most direct form of family support, intergenerational support from children mainly refers to the connection between children and parents through material and

spiritual sharing in social life, which is characterized by directness, selflessness and sustainability. Intergenerational support can be broadly divided into financial support, emotional

communication, and life care. The three types of support are based on the medium of children to combine their influence on the economic life, physical health, mental condition, and rights

protection of the elderly. When more intergenerational support from children means that the elderly has more resource endowment advantages to cope with various life crises, their incidence

of multidimensional poverty is naturally reduced (Huang & Fu, 2021). INTERGENERATIONAL ECONOMIC SUPPORT AND MULTIDIMENSIONAL POVERTY AMONG OLDER ADULTS In the context of traditional

Chinese culture, financial support from children is the basic source of livelihood for the elderly, which mainly refers to the direct financial help and material support from children to

provide the elderly with daily living security, medical financial security, as well as the purchase of household appliances and daily nutritional products. Moderate financial support can not

only ensure the daily expenses of the elderly, improve their living conditions and maintain their physical health, but also reduce the probability of the elderly falling into

multidimensional poverty as they grow older and their bodies gradually decline, allowing them to have the capital to engage in their own hobbies and maintain a good emotional experience of

the elderly. Of course, the effect of intergenerational economic support on the occurrence of poverty in different dimensions is not entirely consistent (Liu, 2018). In essence, children

provide financial support to their parents to meet the missing needs of the elderly in old age, which is an important livelihood guarantee for the elderly after the loss of basic working

ability. The fundamental purpose is to ensure the material aspects of the elderly’s life through monetary transfers so that the elderly have sufficient ability to pay for living expenses,

medical and health care costs, etc., and ensure that the elderly do not fall into economic poverty and health crises. In the non-material aspects, such as spiritual comfort and rights

protection, financial support is obviously less effective than emotional support and care support. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed: H1: Intergenerational economic

support can significantly alleviate the occurrence of multidimensional poverty among the elderly, but there are differences in the effects on different types of poverty among the elderly.

INTERGENERATIONAL CAREGIVING SUPPORT AND MULTIDIMENSIONAL POVERTY IN OLDER ADULTS Caregiving support is from the perspective of family daily life, which refers to the daily and continuous

care provided by children to the elderly through the provision of living accommodation, food, daily care, security protection, and companionship, and has an important impact on the

alleviation of multidimensional poverty of the elderly. Specifically, the provision of daily care by children to their parents is in line with the traditional filial culture of family

elderly care, which not only ensures the normalization of the daily life of the elderly, such as "clothing, food, housing, transportation and use", but also conveys the care of

children to the elderly, promotes the emotional communication between the two generations, and is conducive to improving the spiritual comfort and life satisfaction of the elderly. Studies

have shown that during the caregiving process, children’s careful care and verbal interaction and communication between children and parents strengthen the psychological expectation of the

elderly to "take care of themselves", which leads to a positive attitude toward self-aging (Sun, 2004), relieves the anxiety and psychological anxiety of the elderly, and improves

their health status. Inadequate daily care can reduce the welfare level of the elderly and adversely affect their life, mental and health (Moeini et al., 2018), increasing their probability

of falling into multidimensional poverty. Of course, some scholars have also pointed out that under the parent-child living pattern, older adults may take on some household chores or

grandchild care responsibilities as a way to give back and compensate for the support of their offspring (Ma & Wen, 2016). This will squeeze the leisure time of the elderly to a certain

extent and prevent them from freely pursuing their preferences, which negatively affects the protection of their rights (Yuan & Chen, 2019). Based on this, the following hypothesis is

proposed: H2: Intergenerational caregiving support can significantly alleviate the occurrence of multidimensional poverty among the elderly, but there are differences in the effects on

different types of poverty among the elderly. INTERGENERATIONAL EMOTIONAL SUPPORT AND MULTIDIMENSIONAL POVERTY IN OLDER ADULTS With the continuous improvement of material living standards,

the content of support for the elderly is also changing. While pursuing material living needs, the elderly are beginning to focus on the pursuit of emotional living needs, and emotional

support has jumped into the public eye. By emotional support it means that children, on the basis of meeting the material needs and living care of the elderly, give the elderly emotional,

psychological and faith care and support through multi-dimensional supply, so that the elderly can spend their old age happily and happily. According to psychologists’ analysis, children’s

emotional support can not only effectively ensure that the elderly are in a good mood, but also keep their metabolism and neuroendocrine regulation at a good level, thus making the elderly

live a happy and healthy life. On the contrary, if the lack of such emotional support, the elderly will be very easy to produce loneliness, bitterness, loneliness and other negative

emotions, accelerating the physical and psychological aging of the elderly, and may even induce depression, cardiovascular, senile dementia and other mental and psychological diseases. Some

studies show that elderly people who are often comforted and cared for by their children live 10–15 years longer than those who do not have a good relationship with their children and do not

receive care and love (Shi & Wang, 2013). Thus, as the main form of non-material support, good emotional support has an important positive effect on securing the life, spirit and health

of the elderly, and is conducive to alleviating their multidimensional poverty (Abolfathi et al., (2014)). It is worth stating that the effectiveness of emotional support is achieved

through positive emotional reinforcement, family relationship regulation, and rational catharsis of stress, aiming to reduce the sense of worry, loneliness, and social isolation in the

elderly, and to enhance their psychological resilience, self-confidence, and optimism. Therefore, it has more impact on the mental and health of the elderly, and less impact on the economic

and rights of the elderly. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed: H3: Intergenerational emotional support can significantly alleviate the occurrence of multidimensional

poverty among the elderly, but there are differences in the effects on different types of poverty among the elderly. MODERATING EFFECTS OF SOCIAL SECURITY Social security is an important and

indispensable social and economic system in modern society, as well as a livelihood protection system that promotes social well-being. Since China’s reform and opening up, it has now built

the largest social security system in the world, with the system covering various items such as social insurance, social assistance, social welfare and military protection. According to

statistics, by the end of 2021, the number of people participating in China’s national basic medical insurance reached 1.36 billion, with the coverage stabilising at over 95%; the number of

people participating in China’s basic pension insurance, unemployment insurance and work injury insurance stood at 1.03 billion, 230 million and 280 million respectively; and the number of

China’s social security card holders reached 1.35 billion. As an important means of income redistribution, a stable social security system plays an important role in the elimination of

individual multidimensional poverty. In particular, for elderly people in vulnerable groups, in addition to the financial, moral and care support they can receive from their children, a

stable social security system is an important guarantee against falling into economic, health and livelihood poverty (Dimova & Wolff, 2008). On the one hand, the social security system

can effectively reduce the financial pressure of the elderly through programmes such as pension insurance, medical insurance and housing security; on the other hand, the social security

system can also help the elderly to obtain daily care and emotional companionship through services such as community elderly care services, medical services and psychological counselling,

giving them more autonomy in their life choices, thus reducing the likelihood of the elderly falling into poverty in a multi-dimensional manner. It is worth noting that intergenerational

support from children and social security are systematically complementary, with social security systems having a greater impact on multidimensional poverty when intergenerational support

from children is weak, and intergenerational support from children acting as a substitute when government support is less effective (Grootaert & Narayan, 2004). It is inferred that the

presence of a social security system will affect the impact of intergenerational support on multidimensional poverty to some extent due to the substitutability of the two functions, and that

when there are differences in the social security status of the elderly, their dependence on their children will be affected and the impact of intergenerational support on multidimensional

poverty will naturally vary. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed: H4a: Social security play a moderating role between intergenerational financial support and

multidimensional poverty among the elderly. H4b: Social security play a moderating role between intergenerational care support and multidimensional poverty among the elderly. H4c: Social

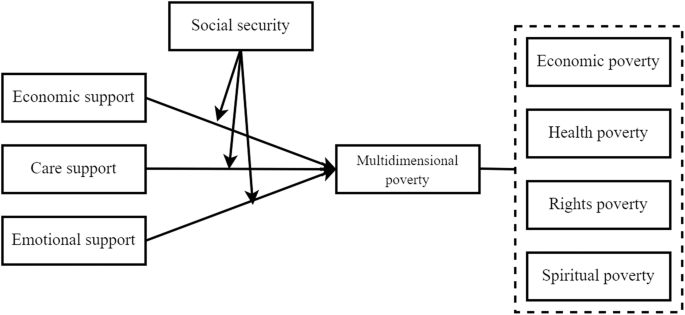

security play a moderating role between intergenerational emotional support and multidimensional poverty among the elderly. In summary, the following theoretical model framework was

constructed to express the relationship more clearly between intergenerational support and multidimensional poverty among the elderly (see Fig. 1). SAMPLE DEFINITION AND DESCRIPTIVE

STATISTICS DATA SOURCE To accurately measure the impact of intergenerational support from children on the multidimensional poverty of older adults, this paper uses data from the CLHLS in

2018. The data were composed surveys of elderly aged 65 and above from 22 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions across China. Approximately 16,000 participants participated in the

CLHLS in 2018, with content including the respondents’ health, economic and living conditions, social welfare, and other aspects. According to the questions selected, this paper has removed

samples whose answers were “I don’t know”, “I’m not sure”, inconsistent, or lacked key variables, to eventually obtain 8061 pieces of valid data. VARIABLES AND DESCRIPTIONS EXPLAINED

VARIABLE The explained variable in this paper is the multidimensional poverty of older adults. According to research findings and data, the four dimensions, i.e., income, health, spirit, and

rights, are selected to comprehensively measure multidimensional poverty. Among them, economic poverty is measured using the question “Are all your sources of livelihood sufficient?” “Yes”

is assigned a value of 0, and “No” is assigned a value of 1, meaning economic poverty. Health poverty is measured by the older adults’ evaluation of their health using the question “How do

you think of your health at present?” “Very good”, “Good”, or “Average” is assigned a value of 0, while “Poor” or “Very poor” is assigned a value of 1, meaning health poverty. Spiritual

poverty is measured using the question “Do you feel lonely?”, with the respondents’ answer of “Seldom” or “Never” assigned a value of 0, and “Always”, “Often”, or “Sometimes” assigned a

value of 1, meaning spiritual poverty. Rights poverty is measured according to the making of personal life decisions using the question “Do you decide your own affairs?”, with the answer of

“Always”, “Often”, or “Sometimes” assigned a value of 0, meaning no rights poverty, and the answer of “Seldom” and “Never” assigned a value of 1, meaning rights poverty. In addition, to

highlight the importance of the elderly’s subjective perception of multidimensional poverty, this paper draws on the practice of existing scholars (Song et al., 2019), taking into account

the reality of China, and defines poverty as multidimensional poverty if at least two dimensions of income poverty, health poverty, spiritual poverty, and rights poverty exist in the sample,

and assigns a value of 1. Conversely, the absence of poverty or the presence of only a single dimension of poverty is considered to be the absence of multidimensional poverty and is then

assigned a value of 0. EXPLANATORY VARIABLE The core explanatory variable in this paper was intergenerational support from children, which was measured using three dimensions, i.e.,

economic, emotional, and care support. Economic support was measured based on the respondents’answer to the question “How much cash (or in-kind equivalent) have your children given you over

the past year?” To eliminate data-level effects, the amounts were logarithmized for analysis. Emotional support was measured using the question “Who do you usually talk to the most?” The

respondents’ answers that included children were assigned a value of 1, and other answers were assigned a value of 0. Care support was measured using the question “Currently, who takes care

of you when you are unwell or sick?” The respondents’ answers, including children, were assigned a value of 1, and other answers were assigned a value of 0. ADJUSTMENT VARIABLE The

moderating variable in this paper is the social security scheme and the question "What social security do you currently have?" is used as the operationalisation question for the

elderly. Respondents were assigned a value of 1 for those who chose to have a social security program and 0 for those who chose not to have any social security program. CONTROL VARIABLE To

avoid the impact of omitted variables on the model, this paper also controls for other variables that may affect multidimensional poverty among older people during the empirical testing

process. The control variables include elderly characteristics variables, child characteristics variables, household characteristics variables and regional characteristics variables. The

elderly characteristics variables include gender, age, age squared, household registration and marital status; the child characteristics variables include the number of children, the number

of boys and the proportion of boys; the household characteristics variables include the total income of the whole family and the number of co-residents; and the regional characteristics

variables are defined according to the distribution location and regional classification criteria of the elderly in China, according to the eastern and non-eastern regions. One of the things

to note is that this paper includes both age and age squared in the model in order to further analyse whether there is a positive U or an inverted U relationship. That is, to further

observe whether his marginal impact rises or falls as age increases. DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICAL ANALYSIS The descriptive statistical analysis revealed that the overall incidence of

multidimensional poverty among the elderly was 15.7%, but the number of people experiencing multidimensional poverty in China is still relatively large because of the large base of elderly

people in China. Also, looking at the types of poverty, it can be found that mental poverty has the highest incidence of 26.1%. Older people are poorer due to loneliness, followed by

economic poverty, health poverty and rights poverty, all with an incidence of about 14% (see Table 1). To a certain extent, this indicates that the overall form of multidimensional poverty

among the elderly in China is relatively severe, and the core of poverty is showing the development trend of evolving from material poverty to spiritual poverty. In terms of explanatory

variables, the proportion of elderly people who receive emotional support from their children was 82.3%, indicating that most elderly people communicate with their children in their daily

lives, further highlighting the importance of emotional support from their children to the elderly. The proportion of elderly people who receive care support from their children is 62.7%,

indicating that their children’s care is still the main source of support for them. The logarithmic mean value of income given by children to the elderly was 5.889, highlighting the

importance of financial support from children as an important component of the elderly’s income. In terms of control variables, among the individual characteristics of the elderly, the mean

age of the valid sample group was approximately 84 years, with a higher proportion of elderly people in rural areas. In the characteristics of the children of the elderly, the mean value of

the total number of children was 4.01 and the mean value of the proportion of boys was 0.53, indicating that the majority of the elderly had about four children and the proportion of boys

was about 53%. In terms of household characteristics, the mean value of total annual household income after taking the logarithm is 9.699 and the mean value of the number of people living

together is 2.064. In terms of regional characteristics, the proportion of elderly people in the eastern region is 54.2%, indicating that the effective sample has about the same number in

the eastern and non-eastern regions. RESEARCH MODEL The aim of the study in this paper is to explore the impact of different types of intergenerational support on multidimensional poverty

among the elderly. Considering whether multidimensional poverty occurs as a dichotomous variable, a binary logit regression model was chosen for the analysis in this study. The specific

expression of the model is as follows: $$Logit\left( P \right) = Ln\left[ {P/1 - P} \right] = \alpha + {\sum} {\beta _j} X_j + \varepsilon$$ (1) In Eq. (1), P denotes the probability of the

elderly falling into multidimensional poverty, P/(1-P) is the ratio of the probability of the elderly falling into multidimensional poverty to the probability of not falling into

multidimensional poverty, α is a constant term, and βj is the regression coefficient of the independent variable Xj, ε denoting the random disturbance term. EMPIRICAL TEST BASELINE

REGRESSION To explore the effects of different types of intergenerational support of children on multidimensional poverty among the elderly, this paper incorporates the explained,

explanatory, and control variables into the model simultaneously and uses a binary logit regression model for estimation. In addition, this paper further explores the effects of different

types of intergenerational support on different types of poverty. Models 1–5 are the regression results obtained with multidimensional poverty, economic poverty, health poverty, Rights

poverty, and spiritual poverty as dependent variables, respectively. Details are shown in Table 2. Looking at the effect of children’s financial support on multidimensional poverty and each

type of poverty, it can be found that there is no significant effect of financial support on multidimensional poverty (_p_ > 0.05), and also none of the effects on economic poverty,

health poverty and spiritual poverty of the elderly are significant (_p_ > 0.05). However, economic support had a significant negative effect (P < 0.05) on Rights poverty among older

adults, indicating that the probability of Rights poverty among older adults decreases as children’s economic support increases. Research hypothesis 1 is partially valid. This paper suggests

that the reason for this phenomenon is that the more financial support from children, the stronger the elderly are financially and the more secure they feel in their later years, which to

some extent enhances their confidence in the future and leads to the elderly having more say in their own behavioral decisions. This result is consistent with the connotation of Amartya Sen

(1999) capability poverty theory, which states that an individual’s income is closely related to his capabilities and various activities. In terms of the effect of childcare support on

multidimensional poverty and each type of poverty, it can be found that care support has no significant effect on multidimensional poverty (_p_ > 0.05), and also has no significant effect

on economic poverty, health poverty and mental poverty among the elderly (_p_ > 0.05). However, caregiving support had a significant positive effect on the elderly’s Rights poverty (_P_

< 0.05), indicating that the probability of elderly people experiencing Rights poverty increased with the increase of caregiving support from their children. Research hypothesis 2

partially holds. This paper suggests that there may be two reasons for this phenomenon. One is because when children care for the elderly, it indicates an increased risk to their physical

health, which decreases their self-efficacy and causes them to feel a sense of failure and incompetence, thus making them more vulnerable to Rights poverty. Secondly, it is because under the

parent-child cohabitation residence model, older adults also need to take on some household chores or grandchildren care responsibilities, which will squeeze the leisure time of older

adults to a certain extent and prevent them from freely engaging in their preferences, which negatively affects the protection of their rights (Yuan & Chen, 2019). In terms of the effect

of children’s emotional support on multidimensional poverty and each type of poverty, it was found that emotional support had a significant negative effect on multidimensional poverty,

economic poverty, health poverty, and spiritual poverty among the elderly (_p_ < 0.05), indicating that the probability of multidimensional poverty, economic poverty, health poverty, and

spiritual poverty among the elderly decreased with the increase of children’s emotional support. In addition, intergenerational emotional support did not have a significant effect (_P_ >

0.05) on the elderly’s Rights poverty. Research hypothesis 3 holds. In recent years, along with the increasing improvement of China’s old-age security, financial and care support for the

elderly has become more and more diversified in terms of access. Therefore, financial support from children is no longer the only source of income for the elderly, and pure care support from

children is not what the elderly really want. On the contrary, as they grow older, older adults desire the companionship of their children, but children are too busy working to communicate

with their aging parents, which leads to emotional support becoming an important cause of multidimensional poverty among older adults. In addition, the impact of poverty is seen for each

type of poverty. First, emotional support has a significant effect on economic poverty, which implies that if children can give emotional support and care to their parents, it will reduce

the likelihood of older adults falling into economic poverty. This paper speculates that there are two main reasons for this. On the one hand, this paper uses older people’s subjective

feelings to measure economic poverty, and if children can give more emotional support to their parents, it will significantly improve their subjective well-being and life satisfaction, thus

effectively alleviating older people’s perception of economic poverty (Peng et al., 2015), while simple economic support can hardly produce the same effect. On the other hand, China has made

great achievements in poverty reduction in recent years, reducing absolute poverty, providing more and more support for the care of the elderly, and providing the elderly with multiple

sources of income, which has alleviated economic poverty to some extent. Second, emotional support significantly affects the health poverty of older adults. That is, the more emotional

support they receive, the less likely they are to fall into health poverty. This is because emotional care involves maintaining the relationship between children and parents, which can help

older adults restore their physical functions, effectively reduce their mental stress, and promote a healthier physical and mental state, something that financial and caregiving support may

not be able to provide (Wong et al., 2014). Conversely, a lack of emotional support can lead to feelings of isolation, which can negatively affect physical health (Van Baarsen, 2002). This

further suggests that emotional support from children plays a positive role in the physical health of older adults on a consistent basis, and therefore, older adults desire and need

emotional support more than wealth and simple care (Bourne et al., 2007). Third, emotional support significantly affects older adults’ mental poverty, i.e., the more emotionally supportive

their children are, the less likely older adults are to be in mental poverty. This suggests that communication between older adults and their children can bring them closer to each other,

effectively reduce the loneliness of older adults, and provide better emotional support for older adults. Emotional support based on blood ties plays the most significant role in older

adults’ spiritual poverty (Zimmer & Kwong, 2003). Emotional support and companionship given by children to their parents largely motivate the elderly and provide better spiritual comfort

to them. MODERATING EFFECTS It is well known that multidimensional poverty is a complex issue that involves not only economic poverty in terms of basic household living, but also a range of

non-income poverty conditions. Social security plays an important role in safeguarding people’s livelihoods and regulating income redistribution, and is a central component of the country’s

poverty reduction efforts. On the one hand, social security can play a protective role in lifting people out of poverty. On the other hand, social security can also be effective in

improving resource allocation and alleviating financial difficulties. Social security, as one of the important sources of old age for the elderly, has obvious systemic complementarity with

intergenerational support from children. Therefore, based on the comprehensive consideration that the explained variables, explanatory variables and moderating variables in this paper are

all categorical variables, in order to further verify the moderating effect of the social security scheme between intergenerational support and multidimensional poverty of the elderly, this

paper divided the participation in the social security scheme and non-participation in the social security scheme into 2 groups for separate regression analysis. The data results are shown

in Table 3. It can be found that care support did not have a significant effect (_p_ > 0.05) on multidimensional poverty among the elderly, both in the group of elderly people who

participated in the social security scheme and in the group of elderly people who did not participate in the social security scheme, at which point there was no moderating effect,

inconsistent with research hypothesis H4b. However, in the group of elderly people who participated in the social security scheme, financial support from children had no effect on

multidimensional poverty (_p_ > 0.05), whereas in the group of elderly people who did not participate in the social security scheme, financial support from children had a significant

negative effect on multidimensional poverty (_p_ < 0.05), at which point there was a moderating effect, consistent with hypothesis H4a. At the same time, children’s emotional support had

a significant negative effect on multidimensional poverty in the group of elderly people who participated in the social security scheme (_p_ < 0.05), while in the group of elderly people

who did not participate in the social security scheme, children’s emotional support had no effect on multidimensional poverty in the elderly (_p_ > 0.05), at which point there was a

moderating effect, in line with the research hypothesis H4c. It is also worth noting that these results further suggest that when the elderly have a more comprehensive social security

programme, their needs are more emotionally oriented and they expect more emotional support from their children. For those who do not have a comprehensive social security programme, their

needs are more financially oriented and they are more dependent on their children for financial support. ROBUSTNESS TEST To further enhance the credibility of the baseline findings, as well

as to overcome possible endogeneity issues with the model, robustness tests are next conducted through propensity score matching, sample replacement, and model replacement. PROPENSITY SCORE

MATCHING The commonly used robustness tests contain five categories, which are the replacement variable method, variable supplementation method, changing sample size method, split-sample

regression method, and model replacement method. The core idea of the propensity score matching (PSM) method is that if two individuals have the same propensity score, when one of them

belongs to the participant group that receives the item and the other is defined as the non-participant control group, then the outcome Y of the output of the individual in the control group

can be used as the counterfactual of the participant individual. This method can relatively effectively eliminate self-selection bias, is more intuitive than regression estimation, and is

one of the robustness tests used by most scholars (Hu & Zhou, 2014). Therefore, this paper also chooses the propensity score matching method to further analyze the effect of children’s

emotional support on multidimensional poverty among the elderly. In the above analysis, children’s emotional support had a significant effect on multidimensional poverty among older adults.

To test the reliability of the results more accurately, the PSM method was chosen for this paper to further explore and overcome the possible endogeneity problem of the model, and the common

nearest neighbor matching method was also chosen. The absolute value of the post-matching standard deviation is equal to 10 is usually regarded as the criterion of matching effect, in

which, if the absolute value of the post-matching standard deviation is less than 10, the matching effect is considered good; on the contrary, the matching effect is considered poor (Chen,

2016). As can be seen from Table 4, the standard deviation of the feature variables of both groups of samples decreased after matching, and the absolute values were less than 10. the

differences in features between the two groups of samples were eliminated to some extent, and the matching effect was good. To ensure the robustness of the results, this paper explored the

average treatment effect of child emotional support on multidimensional poverty among older adults using nearest-neighbor matching. According to the mean treatment effects estimated in Table

5, child emotional support affected the incidence of multidimensional poverty among older adults at the 5% significant level before matching. After matching, the effect of emotional support

on older adults’ multidimensional poverty remained significant at the 1% level, and the average treatment effect results were consistent with the logit regression results, fully indicating

that children’s emotional support can significantly influence the probability of multidimensional poverty among older adults. REPLACING THE SAMPLE To further verify the stability and

reliability of the findings, this study selected the sample located in the east of the region variable by replacing the sample and re-run the binary logit regression on it. The results are

shown in Table 6. It can be found that although the specific effect values of the independent variables on the dependent variable changed, the direction and significance of the effects did

not fluctuate significantly, and the emotional support of children still had a significant negative effect on the multidimensional poverty of the elderly (_p_ < 0.05), which is consistent

with the results of the full sample, again verifying the importance of emotional support on the multidimensional poverty of the elderly. REPLACING THE MODEL To further test the sensitivity

of the regression results to the form of the model set, this paper additionally chose a probit regression model to test the relationship between intergenerational support and

multidimensional poverty among the elderly, and the results of the analysis are shown in Table 7. Where model 1 is the result of adding the independent variables, elderly characteristic

variables, child characteristic variables and household characteristic variables, model 2 is the result of adding all variables to the model. It can be found that the baseline findings of

this paper did not change due to the change in the setting of the model, and the ability of emotional support to significantly and negatively affect the multidimensional poverty of the

elderly still holds (_p_ < 0.05), indicating that the baseline findings are strongly robust. CONCLUSIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS AND SHORTCOMINGS Using CLHLS 2018 data, this paper further

explores the effects of different types of intergenerational support on economic poverty, health poverty, rights poverty, and spiritual poverty among older adults in China, based on the

analysis of the effects of intergenerational economic support, caregiving support, and emotional support on overall multidimensional poverty among older adults aged 65 and older, and uses

group regressions to test for different scenarios of social security participation in which intergenerational support differences in the effects on multidimensional poverty. The results of

the study suggest that: (1) With regard to the overall situation of multidimensional poverty, the situation of multidimensional poverty among the elderly in China has become more and more

serious along with the aging of the population, the normalization of youth mobility, and the acceleration of family structure with fewer children, and the overall incidence of

multidimensional poverty among the elderly in China is relatively large. In terms of the internal structure of multidimensional poverty, compared with the previous basic trend of economic

poverty, the current trend of multidimensional poverty among the elderly in China is evolving from material poverty to spiritual poverty, and the incidence of spiritual poverty is much

higher than that of economic poverty, health poverty and rights poverty. (2) The effectiveness of financial and caregiving support in the current governance of multidimensional poverty among

the elderly in China has gradually diminished, failing to significantly affect the alleviation of overall multidimensional poverty, economic poverty, health poverty, and spiritual poverty.

Both have significant effects only on the rights poverty of the elderly, and in opposite directions. The probability of elderly people’s rights poverty decreases when their children provide

more financial support and increases when their children provide more care support. (3) Emotional support assumes an increasingly important role in the current governance of multidimensional

poverty among the elderly in China. Except for the absence of significant effects on rights-based poverty, emotional support has significant effects on alleviating multidimensional poverty,

economic poverty, health poverty, and spiritual poverty of the elderly. When children provide more emotional support, the probability of multidimensional poverty, economic poverty, health

poverty, and spiritual poverty in old age decreases. (4) Social security programmes have a significant moderating effect on the relationship between financial support, emotional support and

multidimensional poverty among the elderly. When the elderly have a more comprehensive social security programme, their needs are more emotionally oriented, and they expect more emotional

support from their children. For those who do not have a comprehensive social security programme, their needs are more financially oriented, and they are more dependent on their children for

financial support. Based on this, this paper proposes the following recommendations to effectively mitigate the risk of multidimensional poverty among the elderly in China. First,

children’s emotional support is critical in reducing the occurrence of multidimensional poverty among older adults, which further indicates that what older adults need as they grow older is,

not simply economic support from their children, but rather companionship and emotional support. Therefore, the Chinese government should attach importance to children’s emotional support

for older adults, encouraging young people to keep in touch with their parents, and promote the concept of providing for, caring for, and respecting older adults. It is important to build a

social atmosphere that focuses on emotional care, and to pay attention to the creation of an older adult care culture in families and the maintenance of a-holistic care environment. Policy

design should consider promoting children’s visits to their parents and the care of older adults, gradually improve system provisions to assist with “going home often”, constantly improve

the labor leave system, and reasonably adjust holidays, to ensure children’s balance of family and work. Other supporting policies and older adults’ care service resources should be

integrated, to assist children in improving the level of old-age security. Second, older adults with rural household registration and older adults in the central and western regions should

be given priority attention. To alleviate the multidimensional poverty of older adults, it is necessary to coordinate the efforts of all sectors of society and form a system of coordinated

advancement by families, government, and society. For example, social service agencies, voluntary organizations, and other social forces can be broadly mobilized and guided to actively

participate in the governance of multidimensional poverty of older adults and play an active role in serving older adults. The social support networks for the families of older adults can be

reshaped to provide all-around information so that charitable organizations and social workers can fully understand the various aspects of children’s support for older adults and provide

timely reprieve for older adults who may fall into multidimensional poverty with livelihood assistance and spiritual comfort. In the process of helping older adults, attention should be

given to the heterogeneity of multidimensional poverty groups. Social resources should target groups more prone to multidimensional poverty, urban-rural and regional imbalances should be

narrowed, and different targeting methods should be adopted according to local conditions, to provide precise help for older adults in poverty. Third, the improvement of social welfare for

older adults should be accelerated, and a tiered and classified social assistance system should be built so that more elderly people can fully enjoy diversified care services, obtain more

stable security, and realize appropriate care. The medical service and health system should be further improved, the coverage of medical insurance for older adults should be increased, older

adults’ disease treatment and health should be guaranteed by increasing government financial investment and strengthening the management of medical insurance coverage, and a safety net that

can stabilize older adults in terms of economy, health, spirit, and rights should be constructed to alleviate the occurrence of multidimensional poverty among older adults. The government

may take active measures to encourage older adults to choose social security programs suitable for their care, and set up several alternative systems for older adults, to enhance their

ability to cope with future risks and alleviate their probability of falling into multidimensional poverty. In addition, the establishment or improvement of systems for the identification

and dynamic monitoring of multidimensional poverty of older adults should be considered, to accurately identify the multiple dimensions and form two lines of defense for the governance of

the multidimensional poverty of older adults. This study also has certain limitations: in terms of the study population, the analysis is mainly unified for a sample consisting of urban and

rural elderly together, without delving into the differences in the relationship between intergenerational support and multidimensional poverty among elderly people of different household

registration. Given the spatial heterogeneity and uneven development of China’s urban and rural areas, future research should further refine the scope of the study to investigate the impact

of different types of intergenerational support on multidimensional poverty among rural and urban elderly, and to reveal and analyse the differences between them. DATA AVAILABILITY The

datasets analysed during the current study are available in the Dataverse repository: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/1YE9B6. REFERENCES * Abolfathi

MY, Ibrahim R, Hamid T (2014) The impact of giving support to others on older adults’ perceived health status. Psychogeriatrics 14(1):31–37 Article Google Scholar * Alkire S, Foster J

(2011) Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J Public Econ 95(7):476–487 Article Google Scholar * Atkinson A (2003) Multidimensional Deprivation: Contrasting Social Welfare

and Counting Approaches. J Econ Inequal 1(1):51–65 Article Google Scholar * Bai C, Lei XY (2020) New trends in population aging and challenges for China’s sustainable development. China

Econ J 13(1):3–23 Article Google Scholar * Bourne V, Fox H, Starr J et al. (2007) Social support in later life: Examining the roles of childhood and adulthood cognition. Pers Individ

Differ 43(4):937–948 Article Google Scholar * Chen J, Jordan L (2018) Intergenerational Support in One- and Multi-child Families in China: Does Child Gender Still Matter? Res. Aging

40(2):180–204 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Chen J, Rong S, Song M (2020) Poverty Vulnerability and Poverty Causes in Rural China. Soc Indic Res 153(1):65–91 Article Google Scholar *

Chen Q (2016) _Advanced econometrics and Stata applications_. Higher Education Press, Beijing. (in Chinese) * Cheng LG, Liu H, Zhang Y et al. (2018) The health implications of social

pensions: Evidence from China’s new rural pension scheme. J Comp Econ 46(1):53–77 Article Google Scholar * Ci QY, Ning WW (2018) Research on social support of the old-age in poverty in

response to weakening family support. Chin J Popul Sci 4:68-80+127. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Cong Z, Silverstein M (2008) Intergenerational Time-for-Money Exchanges in Rural China:

Does Reciprocity Reduce Depressive Symptoms of Older Grandparents? Res Hum Dev 5(1):6–25 Article Google Scholar * Decerf B (2020) Combining absolute and relative poverty: Income poverty

measurement with two poverty lines. Soc Choice Welf 56(2):325–362 Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * Deng DS, Wu ZY, Yang J (2019) Practical dilemma and Path Optimization of

China’s rural poverty alleviation Policy – Also on the connection between rural poverty alleviation and subsistence allowance system. J Suzhou Univ (Philos Soc Sci Ed) 05:93–102. (in

Chinese) Google Scholar * Dimova R, Wolff F (2008) Are private transfers poverty and inequality reducing? Household level evidence from Bulgaria. J Comp Econ 36(4):584–598 Article Google

Scholar * Foster JE (2007) A Class of Chronic Poverty Measures. Vanderbilt University Department of Economics Working Papers No. 0701 * George K, Bearon LB (1980) Quality of life in older

persons: Meaning and measurement. Human Sciences Press, New York Google Scholar * Gorman M, Heslop A (2002) Poverty, policy, reciprocity and older people in the South. J Int Dev

14(8):1143–1151 Article Google Scholar * Grootaert C, Narayan D (2004) Local Institutions, Poverty and Household Welfare in Bolivia. World Dev 32(7):1179–1198 Article Google Scholar *

Guo M (2014) Parental status and late-life well-being in rural China: the benefits of having multiple children. Aging Ment Health 18(1):19–29 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Guo XB, Zhou

Q (2016) Chronic multidimensional poverty, inequality and causes of poverty. Econ Res J 51(6):143–156. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Hagenaars A (1987) A Class of Poverty Indices. Int Econ

Rev 28(3):583–607 Article MATH Google Scholar * Huang FH, Fu PP (2021) Intergenerational support and subjective wellbeing among oldest-old in China: The moderating role of economic

status. BMC Geriatr 21(1):252 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hu YY, Zhou ZF (2014) Policy treatment effect evaluation based on propensity score matching. Chin Public Adm

343(1):98–101. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Jiao C, Leng A, Nicholas S et al. (2020) Multimorbidity and mental health: the role of gender among disease-causing poverty, rural, aged

households in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(23):1–12 Article Google Scholar * Krause N (2001) Social Support. In: Binstock RL and George LK (eds.) Handbook of Aging and the

Social Sciences, 5th ed. CA: Academic, San Diego, p 273-294 * Lai DWL, Leonenko W (2007) Effects of Caregiving on Employment and Economic Costs of Chinese Family Caregivers in Canada. J Fam

Econ Iss 28(3):411–427 Article Google Scholar * Li XY, Li Z, Tang LX et al. (2005) Development and validation of a participatory poverty index. Chin Rural Econ 5:39–46. (in Chinese) Google

Scholar * Liu EP (2018) Movement trend of the elderly poverty and influencing factors: Based on multidimensional poverty and comparative perspective. J Hunan Agric Univ (Soc Sci)

19(3):77–83. (in Chinese) MathSciNet Google Scholar * Ma S, Wen F (2016) Who Coresides With Parents? An Analysis Based on Sibling Comparative Advantage. Demography 53(3):623–647 Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Moeini B, Barati M, Farhadian M et al. (2018) The Association between Social Support and Happiness among Elderly in Iran. Korean J Fam Med 39(4):260–265 Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Peng H, Mao X, Lai D (2015) East or West, Home is the Best: Effect of Intergenerational and Social Support on the Subjective Well-Being of Older

Adults: A Comparison Between Migrants and Local Residents in Shenzhen, China. Ageing Int 40(4):376–392 Article Google Scholar * Pinilla-Roncancio M (2018) The reality of disability:

Multidimensional poverty of people with disability and their families in Latin America. Disabil Health J 11(3):398–404 Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rowles G, Johansson H (1993)

Persistent Older adults Poverty in Rural Appalachia. J Appl Gerontol 12(3):349–367 Article Google Scholar * Sen A (1999) Development as Freedom. Oxford University Press, London Google

Scholar * Shi JQ, Wang YZ (2013) On the construction of old-age spiritual security system. Soc Secur Stud 2:3–15. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Song JH, Zheng JX, Wang W (2019) Whether

raising children can support the elderly: The impact of intergenerational interaction on rural multidimensional poverty. Popul Dev 25(6):96–106. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Sun JM, Zhang

GL (2018) Research on the Multidimensional Poverty of the Disabled Older adults in China under the Background of Targeted Poverty Alleviation—Based on the 2014 China Older adults Health

Influencing Factors Tracking Survey. Surv world 12:8–13. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Sun R (2004) Worry about Medical Care, Family Support, and Depression of the Elders in Urban China.

Res Aging 26(5):559–585 Article Google Scholar * Sun YZ (2017) Among a Hundred Good Virtues, Filial Piety is the First: Contemporary Moral Discourses on Filial Piety in Urban China.

Anthropol Q 90(3):771–799 Article Google Scholar * Tsui KY (2002) Multidimensional poverty indices. Soc Choice Welf 19(1):69–93 Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar * UNDP (2010)

Human Development Report 2010(20th Anniversarv Edition). Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke Google Scholar * Van Baarsen B (2002) Theories on coping with loss: The impact of social support and

self-esteem on adjustment to emotional and social loneliness following a partner’s death in later life. J Gerontol Ser B-Psychol Sci Soc Sci 57(1):33–42 Google Scholar * Von Maltzahn R,

Durrheim K (2008) Is Poverty Multidimensional? A Comparison of Income and Asset Based Measures in Five Southern African Countries. Soc Indic Res 86(1):149–162 Article Google Scholar * Wang

XL, Shang XY, Xu LP (2011) Subjective Well-being Poverty of the Older adults Population in China. Soc Policy Adm 45(6):714–731 Article Google Scholar * Wang XL (2017) _Poverty

measurement: theory and methods_ (2nd ed.). Beijing Social Science Literature Press, Beijing.(in Chinese) * Wicks-Lim J, Arno PS (2017) Improving population health by reducing poverty: New

York’s Earned Income Tax Credit. SSM-Popul Health 3(6):373–381 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wong S, Wu A, Gregorich S et al. (2014) What Type of Social Support

Influences Self-Reported Physical and Mental Health Among Older Women? J Aging Health 26(4):663–678 Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yang J, Mukhopadhaya P (2018) Is the

ADB’s Conjecture on Upward Trend in Poverty for China Right? An Analysis of Income and Multidimensional Poverty in China. Soc Indic Res 143(2):451–477 Article Google Scholar * Yang Y, Deng

H, Yang Q et al. (2020) Mental health and related influencing factors among rural older adults in 14 poverty state counties of Chongqing, Southwest China: a cross-sectional study. Environ

Health Prev 25(1):51 Article MathSciNet Google Scholar * Yi YX (2018) A study of the poverty incidence mechanism of China’s urban elderly population. J Yunnan Minzu Univ (Philos Soc Sci)

35(6):99–105. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Yin XX, Zhou R (2021) Socio-economic Status, Intergenerational Support Behavior and Health Poverty in Old Age: Based on the Empirical Analysis of

2113 Urban Elderly Living alone in Five. Cities. Popul Dev 27(5):46–57. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Yu CY, Dong ML, Ma RL (2019) Intergenerational Relationship Quality and Rural Elderly

Poverty in China–An Empirical Analysis Based on a Rural Household Survey of 1395 Farmers from 12 Provinces in China. J Agrotechnical Econ 5:27–38. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Yuan D, Chen

T (2019) The impact of family elder care on adult children’s mental health: The mediating effect of time and income. South Chin Popul 34(6):50–64. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Zhang HM

(2017) Sending parents to nursing homes is unfilial? An exploratory study on institutional elder care in China. Int Soc Work 62(1):351–362 Article Google Scholar * Zhang QH, Zhou Q (2015)

Poverty measurement: Multidimensional approaches and an empirical application in China. Chin Soft Sci 7:29–41. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Zhang QQ (2021) An empirical study on the

influence of intergenerational support on spiritual poverty among the elderly in urban and rural areas. Hubei Agr Sci 60(23):205–210. (in Chinese) CAS Google Scholar * Zhang Y, Wan GH, Shi

QH (2013) Analysis of the measurement, decomposition and determinants of temporary and chronic poverty. Econ Res J 48(4):119–129. (in Chinese) CAS Google Scholar * Zhen C, Silverstein M

(2012) Custodial Grandparents and Intergenerational Support in Rural China. Springer Neth 109–127 * Zhong C, Lin MG (2020) Multidimensional deprivation of relatively poor families in China

and its influencing factors. J Nanjing Agric Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 20(4):112–120. (in Chinese) Google Scholar * Zimmer Z, Kwong J (2003) Family size and support of older adults in urban and

rural China: current effects and future implications. Demography 40(1):23–44 Article PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This article is a stage result of a major

project of the National Social Science Foundation of China, "Research on the realization path of relative poverty governance in the context of building a moderately prosperous society

in all aspects", No. 22&ZD060. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * School of Public Administration, Sichuan University, 610064, Chengdu, China Hong Tan, Zhihua Dong &

Haomiao Zhang Authors * Hong Tan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Zhihua Dong View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Haomiao Zhang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS HT: data processing and analysis, core ideas

development, paper content writing, paper revision. Z-HD: data acquisition, data processing and analysis, paper content writing, paper revision. H-MZ: Selection of thesis topic, development

of research method and technical route, elaboration of core ideas, writing of thesis content. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Haomiao Zhang. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICAL APPROVAL This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. INFORMED CONSENT This article

does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional

claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which

permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless

indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or

exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints

and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Tan, H., Dong, Z. & Zhang, H. The impact of intergenerational support on multidimensional poverty in old age: empirical analysis

based on 2018 CLHLS data. _Humanit Soc Sci Commun_ 10, 439 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01924-3 Download citation * Received: 20 December 2022 * Accepted: 06 July 2023 *

Published: 26 July 2023 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01924-3 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(999x0:1001x2)/pamela-hupp-1-90ba04e3a5284176adfc1272cc2acec6.jpg)