- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The impact of social restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic on social isolation and loneliness has been widely debated, yet little attention has been given to identifying

particularly vulnerable groups. In this study, we analysed data from 8,042 participants of the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS) through a prospective design with multiple follow-ups,

integrating genetic, health, and socioeconomic information to identify distinct loneliness trajectories during the pandemic. Using the 3-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (UCLA-3), we found that

self-reported loneliness increased in parallel with social restriction index, with women being particularly affected. We identified three distinct loneliness trajectories: high loneliness,

pandemic loneliness, and low loneliness. Individuals in the high and pandemic loneliness trajectories both had higher polygenic scores (PGS) for loneliness and for the personality trait

neuroticism compared to the low loneliness trajectory. The high loneliness trajectory was additionally associated with high PGS for psychiatric disorders and low PGS for the personality

trait extraversion in addition to a higher proportion of pre-pandemic psychiatric disorder diagnoses. In contrast, the pandemic loneliness trajectory was linked to low PGS for the

personality traits agreeableness and conscientiousness, as well as higher PGS for religious participation. These findings highlight the need for tailored interventions targeting individuals

with poor mental well-being. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS LONELINESS AND DEPRESSION: BIDIRECTIONAL MENDELIAN RANDOMIZATION ANALYSES USING DATA FROM THREE LARGE GENOME-WIDE

ASSOCIATION STUDIES Article 21 September 2023 UNDERSTANDING THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN SOCIAL ISOLATION, AGE, AND LONELINESS DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC Article Open access 02 January 2025

OBSERVATIONAL AND GENETIC EVIDENCE DISAGREE ON THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN LONELINESS AND RISK OF MULTIPLE DISEASES Article Open access 16 September 2024 INTRODUCTION Loneliness is a feeling

that arises when the quantity and quality of the available social relations do not match an individual’s social needs1. High levels of loneliness have been associated with several adverse

outcomes including poor physical health2, low sleep quality3, low cognitive ability4 and poor mental health5, indicating that loneliness could both contribute to development and worsening of

disease as well as being a marker of poor health generally. Recent research has increasingly pointed to the heritable nature of loneliness with genetic factors accounting for a considerable

portion of the variance in experienced loneliness6,7. Polygenic scores (PGS), which aggregate the effects of numerous genetic variants associated with a trait have shown potential in

predicting susceptibility to loneliness. This genetic predisposition also exhibits pleiotropy, sharing genetic architecture with other psychological traits and health conditions, which

underscores the complex interplay between genetics and environmental factors in the manifestation of loneliness8,9. In addition to PGS’s numerous other individual characteristics such as

prior psychiatric disorders, personality traits (i.e. the ‘big five’: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism), sex, and year of birth have previously been

associated with loneliness6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Furthermore, macro-level factors which impact how individual characteristics are distributed at a societal level or even internationally,

have been shown to impact levels of loneliness15,16,17. For example, implementation of social restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic impacted social norms and behaviours18, and

individuals are likely to have been impacted differently as a result of personal characteristics. An increasing amount of research is focusing on the impacts the COVID-19 pandemic had on

loneliness19,20,21. This mainly stems from government enforced lockdowns, which included prohibiting social gatherings. These lockdowns would have imposed strains on individuals’ social

networks and relationships leading to concerns about general physical and mental wellbeing during and after the pandemic22,23. Most of the studies conducted, including a study of Danish

blood donors24, have reported a general increase in loneliness during the pandemic25, although some studies reported stable levels of loneliness during the pandemic26,27. However, efforts to

identify specific patterns (trajectories) of loneliness to more efficiently characterise sub-groups of individuals vulnerable to experiencing loneliness are very sparse. This impacts our

ability to effectively intervene against loneliness, address potential long-term consequences, and direct strategies towards individuals prone to experiencing loneliness. Hence, identifiers

of distinct loneliness vulnerability profiles are needed. The primary aim of this study was to identify distinct trajectories of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic and characterise

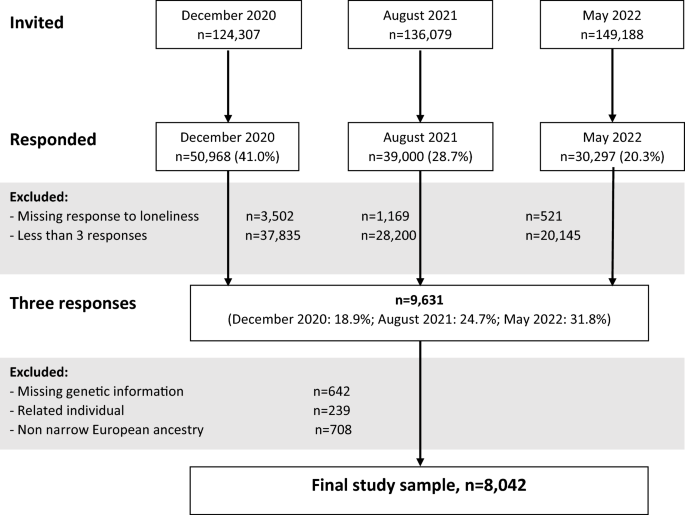

their profiles using genetic, health and socioeconomic data. METHODS STUDY POPULATION AND DESIGN The present study was based on a sample of 8,042 participants from the Danish Blood Donor

Study (DBDS). The DBDS is an ongoing nationwide prospective cohort study that is described in further detail elsewhere28. During the COVID-19 pandemic, questionnaires were sent to DBDS

participants to monitor health and wellbeing including loneliness during different stages of the pandemic. Participants in the present study all reported their prospective level of

loneliness at three timepoints during the pandemic (December 2020, August 2021, and May 2022) as well as their retrospective pre-pandemic level of loneliness (December 2020). They all had

available genetic information for calculation of PGS, were classified as having European ancestry (see appendix—Supplementary Methods 1 for description of ancestry classification) and were

genetically unrelated to other study participants (king-cut-off < 0.084 for study participants) (Fig. 1) (see appendix—Supplementary Methods 2 for description of relatedness analysis).

EXPOSURE Polygenic scores (PGS) for the following traits were calculated and included as identifiers of potential distinct loneliness trajectories: loneliness, all ‘big five’ personality

traits, religious participation, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (see

appendix—Supplementary Methods 3 for a detailed description of PGS calculation). COVARIATES SOCIAL RESTRICTION INDEX The social restriction levels in place at the time of data collection

(December 2020, August 2021, and May 2022) were obtained using the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT), which has been described in length elsewhere29. For each of the

time points, we used the mean OxCGRT restriction level in Denmark over the three months prior to the respective time point. DEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS Information on sex and year of birth was

obtained from the Danish civil registration system that holds this information for all individuals alive in Denmark on April 2, 1968 and onwards30. In addition, employment status (full time

employment, part time employment, self employed, student, unemployed, retired and other) and cohabitation status denoting if an individual lived alone were obtained from questionnaire

responses in December 2020. PRE-PANDEMIC PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS Any pre-pandemic (i.e., before 01 Jan 2020) psychiatric disorder were defined according to the 10th revision of the

international classification of diseases (ICD-10), using the entire F-chapter. Information on psychiatric disorders was obtained from the Danish national patient registry, holding

information on psychiatric disorders diagnosed at a psychiatric hospital department in Denmark since 199531. In addition, prescriptions of psychotropic medication (Anatomical Therapeutic

Chemical [ATC] classification codes N05A, N05B, N06A, and N06AB) redeemed from Danish pharmacies were included to describe psychiatric disorders treated in a primary care setting. The Danish

prescription register contains information on all redeemed prescriptions at Danish pharmacies since 199532,33. OUTCOME LONELINES Levels of loneliness were measured with the University of

California, Los Angeles Loneliness Scale in its three-item form (UCLA-3). This scale has been described in greater detail elsewhere34,35,36, but briefly, UCLA-3 is a shortened version of the

revised UCLA loneliness scale (R-UCLA). R-UCLA has been translated into Danish with high reliability and validity and correlates highly with UCLA-3, indicating that UCLA-3 is a high-quality

measure of loneliness. Each of the three items in UCLA-3 is rated on a scale from 1–3, resulting in a combined loneliness score ranging from 3–9, with 9 indicating the highest level of

loneliness. Scores above 6 are normally regarded as an indicator of loneliness37. STATISTICAL ANALYSES CLUSTER ANALYSIS K-means cluster analysis was used to identify distinct loneliness

trajectories over time by grouping individuals based on their repeated loneliness scores, revealing different pathways of loneliness experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. To select the

appropriate K number we used the between and within cluster sum of squares ratio for each K. This metric both measures the degree of within cluster compactness and the amount of separation

between clusters. When evaluating these values we used the elbow method, which indicated the point at which the between and within-cluster sum of squares ratio diminished., Based on this K =

3 was selected as the appropriate number of clusters (_high loneliness, pandemic loneliness_ and _low loneliness. See results._). To check the stability of trajectories for K = 3, and to

ensure robustness against local minima, the clustering process was repeated 100 times, each with a unique random initialization, ensuring a unique starting point for each run. This was done

to reduce the likelihood of the results being influenced by unfortunate initial centroid placements, which can lead to suboptimal clustering due to the algorithm’s susceptibility to local

minima. Each iteration used nstart = 10, which initializes the centroids 10 times per run and selects the best solution based on within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS). WCSS is a measure of

the compactness of clusters, calculated as the sum of squared distances between each data point and its cluster centroid. The 100 clustering runs were ranked based on WCSS values. The ten

runs with the lowest WCSS were classified as the "best runs," while the ten runs with the highest WCSS were classified as the "worst runs." For both groups,

within-cluster variances were compared to evaluate clustering quality and stability. The best runs had a mean WCSS of 28,391.63, while the worst runs had a slightly higher mean WCSS of

28,399.47, indicating a marginal difference in clustering compactness. The minimal difference between the best and worst runs suggested that the k-means algorithm consistently converged to

near-optimal solutions. Only 146 individuals (1.8% of total individuals) had alternative clustering assignments between the best and worst runs in terms of WCSS. Clustering was identical for

the ten best runs, reflecting a measure of robustness in the clustering process. K-means analysis was performed in rstudio with cluster analysis and metrics processed using the fpc and

cluster packages38,39. DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS Descriptive characteristics of the study were calculated for all study participants and for identified trajectories (Table 1). This included

count and percentages of decade of birth, each sex, cohabitation status, employment status and prevalence of any pre-pandemic psychiatric disorder and redeemed prescriptions of psychotropic

medication. POLYGENIC PROFILES Polygenic profiles of the three identified trajectories were assessed in multinomial logistic regression models where the trajectories _high loneliness_ and

_pandemic loneliness_ were compared with the trajectory _low loneliness_. A total of 12 multinomial regression models were created, using an indicator variable for trajectory (_high

loneliness, pandemic loneliness,_ or _low loneliness_) as the dependent variable and each PGS as the independent variable adjusted for the first ten principal components (see appendix

Supplementary Methods 3 for detailed description of principal components calculation). RELATIONSHIP WITH DEPRESSION To investigate the relationship between symptoms of depression and

loneliness, depression scores for individuals in our study were obtained at four time points during the pandemic (May 2020, December 2020, August 2021, and May 2022). Symptoms of depression

were estimated using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 instrument (PHQ-9). PHQ-9 is a standardised, validated, multi-purpose instrument used for screening, diagnosis and measurement of

depression. PHQ-9 contains nine questions that are rated on a scale from 0–3, resulting in an overall score of 0–27, with 27 indicating the highest level of depression symptoms. PHQ-9 has

been described in depth elsewhere40. The correlation between depression scores and loneliness was calculated in the entire study sample and for each response timepoint, using pearson

correlation coefficients. For identified loneliness trajectories mean depression scores were calculated for each time point. ATTRITION ANALYSES Attrition was assessed by comparing the mean

of all included PGSs between individuals with three questionnaire responses (included in the study) and individuals with less than three questionnaire responses. SENSITIVITY ANALYSES Each of

the multinomial models examining the association between PGS and loneliness trajectories were replicated including PGS for loneliness as a covariate. Analyses were performed in RStudio

Server 2023.12.141 with a significance level of 0.05. All the analyses were exploratory with no critical hypothesis. RESULTS LONELINESS AND SOCIAL RESTRICTION INDEX In the entire study

sample, there was a clear relation between the level of loneliness and social restriction index (Fig. 2a). This tendency was most pronounced among females who experienced higher levels of

loneliness at all timepoints compared with males. The difference substantially increased when the social stringency index was at its highest (test of interaction OR = 1.22 [95%

CI:1.15–1.29]) (Fig. 2b). IDENTIFICATION OF DISTINCT LONELINESS TRAJECTORIES Three distinct loneliness trajectories were identified in the study sample: _high loneliness_ (n = 1024),

_pandemic loneliness_ (n = 2555) and _low loneliness_ (n = 4463). The first trajectory, _high loneliness_, included individuals who had an elevated level of loneliness even before the

COVID-19 pandemic. This trajectory also maintained the highest level of loneliness throughout the study period. The _high loneliness_ trajectory appeared pandemic sensitive with mean

loneliness levels exceeding 6 on UCLA-3, which has been used as a threshold for loneliness in other studies37. The second trajectory, _pandemic loneliness_, was characterised by a relatively

low level of both pre- and post-pandemic loneliness with a marked increase during the pandemic. Finally, the third trajectory, _low loneliness_, included individuals who had a stable low

level of loneliness before, during and after the pandemic (Fig. 3a). CHARACTERISTICS OF LONELINESS TRAJECTORIES DESCRIPTIVE CHARACTERISTICS Descriptive characteristics of the three

identified trajectories are displayed in Table 1. The two loneliness trajectories (_high loneliness_ and _pandemic loneliness_) were characterised by a large proportion of females (_high

loneliness:_ 63.3% [95%CI:60.6%–66.5%] and _pandemic loneliness_: 56.2% [95%CI:54.8%–58.6%] vs. _low loneliness_: 47.5% [95%CI:46.0%–48.9%]). The _high loneliness_ trajectory was

distinguished from the other two trajectories (_pandemic loneliness_ and _low loneliness_) by being younger (born after 1970: _high loneliness:_ 51.3% vs _pandemic loneliness_: 38.5% and

_low loneliness_: 28.0%), more likely to live alone (_high loneliness:_ 47.9% [95%CI:44.8%–50.9%] vs. _pandemic loneliness_: 32.8% [95%CI:31.0%–34.6%] and _low loneliness_: 30.9%

[95%CI:29.6%–32.3%]) and having almost double the prevalence of pre-pandemic psychiatric disorders (_high loneliness:_ 10.9% [95%CI:9.0%–12.8%] vs. _pandemic loneliness_: 5.8%

[95%CI:4.9%–6.7%%] and _low loneliness_: 5.0% [95%CI:4.3%–5.6%]) and increased redemption of psychotropic medication (_high loneliness:_ 6.3% [95%CI:4.9%–7.8%] vs. _pandemic loneliness_:

4.5% [95%CI:3.7%–5.3%] and _low loneliness_: 4.7% [95%CI:3.9%–5.1%]). POLYGENIC PROFILES The polygenic profiles of the trajectories are displayed in Fig. 3b where the two loneliness

trajectories (_high loneliness_ and _pandemic loneliness_) were compared with the trajectory _low loneliness_. High PGS for loneliness (_high loneliness:_ OR = 1.19 [95%CI:1.10–1.24],

_pandemic loneliness_: OR = 1.06 [95%CI:1.01–1.10]) and the ‘big five’ personality trait neuroticism (_high loneliness:_ OR = 1.19 [95%CI:1.11–1.25], _pandemic loneliness:_ OR = 1.07

[95%CI:1.02–1.11]) were associated with the loneliness trajectories. Low PGS for the ‘big five’ personality trait extraversion (OR = 0.90 [95%CI:0.83–0.96]), and high PGS for psychiatric

disorders (schizophrenia: OR = 1.07 [95%CI:1.00–1.14], major depressive disorder: OR = 1.21 [95%CI:1.12–1.26], autism spectrum disorder: OR = 1.13 [95%CI:1.06–1.19], and attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder: OR = 1.08 [95%CI: 1.01–1.15]) were associated with the _high loneliness_ trajectory, while low PGS for the ‘big five’ personality traits agreeableness (OR = 0.94

[95%CI: 0.89–0.98]) and conscientiousness (OR = 0.94 [95%CI: 0.89–0.98]), and high PGS for religious participation (OR = 1.06 [95%CI:1.01–1.11]) were associated with the trajectory _pandemic

loneliness._ In the entire study sample, loneliness and symptoms of depression were moderately correlated, with a correlation coefficient of 0.40. This relationship was stable in December

2020 (r = 0.37) and August 2021 (r = 0.37) but increased to 0.46 by May 2022, coinciding with the removal of most pandemic restrictions in Denmark. Each of the three loneliness trajectories

had stable levels of depression symptoms with no marked changes observed throughout the study period. (see Appendix Supplementary Fig. 4). ATTRITION Individuals with less than three

questionnaire responses had statistically significantly higher PGS for schizophrenia (mean, less than three responses: 0.01 [95%CI: 0.00–0.01] vs mean, more than three responses: -0.04

[95%CI: -0.06;-0.01]) and ADHD (mean, less than three responses: 0.01 [95%CI: 0.00;0.02 ] vs mean, more than three responses: -0.05 [95%CI:-0.08;-0.03 ]), while all other PGSs were not

statistically different between these groups (see Appendix Supplementary Fig. 3). SENSITIVITY ANALYSES The polygenetic profiles were generally robust to inclusion of the PGS for loneliness

in the model (see Appendix Supplementary Fig. 2). DISCUSSION In this large cohort study of 8,042 individuals from the DBDS with multiple follow-ups, we found an overall relationship between

loneliness and pandemic restriction stringency index. Additionally, we identified three distinct trajectories of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic: _high loneliness, pandemic

loneliness,_ and _low loneliness_. Compared with individuals in the _low loneliness_ trajectory, individuals in the _high loneliness_ trajectory had higher PGS for loneliness, the ‘big five’

personality trait neuroticism, and each of the major psychiatric disorders. Moreover the individuals in this trajectory had low PGS for extraversion. Individuals in the _pandemic

loneliness_ trajectory had high PGS for loneliness, the ‘big five’ personality trait neuroticism and religious participation in addition to low scores on the ‘big five’ personality traits

agreeableness and conscientiousness. Analysis of the overall data revealed a significant but modest association between levels of reported loneliness and pandemic restriction stringency

index (Fig. 2). Trajectory analysis revealed 55% of study participants reported consistently low levels of loneliness throughout the study period (Fig. 3). However, among the remaining

individuals who reported marked increases in loneliness at the height of the pandemic, the relationship between pandemic restriction stringency index and loneliness showed the impact of

lockdown measures on loneliness but also that the population returned to pre-pandemic levels of loneliness after the pandemic. This reflects a very situational manifestation of loneliness

overall. The observed interaction between sex and restriction stringency index reflects concerns that negative impacts of lockdown measures such as loneliness were felt disproportionately by

women42. This is also corroborated by the loneliness trajectories where the two loneliness trajectories with elevated levels of loneliness had a higher proportion of females compared with

the _low loneliness_ trajectory. Concerns about women’s mental wellbeing generally during the pandemic have been raised in many studies, with suggested factors including asymmetrical impacts

on working life43, childcare burdens44 and domestic violence45. As a result of these potential additional stressors, women may also have experienced increased levels of social isolation.

The three loneliness trajectories identified in this study, including both a dynamic trajectory characterised by high situational loneliness as well as a stable trajectory largely unaffected

by the pandemic, are in line with previous research24,25,26,27. This underscores the existence of different patterns of reaction to restrictions and lockdown depending on the liability of

the individual and their circumstances. High PGS for loneliness and the ‘big five’ personality trait neuroticism were associated with the elevated _loneliness_ trajectories (_low loneliness_

and _pandemic loneliness_). This reflects that individuals with a high genetic liability for loneliness and neuroticism were more vulnerable to experiencing loneliness when macro-levels

factors, like governmental enforced lock-downs were implemented. While it is not surprising that genetic liability for loneliness is associated with higher experienced loneliness, the

results for neuroticism are also in line with the existing research, reporting that individuals with high PGS for neuroticism were more prone to experience loneliness9. It has previously

been reported that individuals scoring high for neuroticism are likely to have disengaging coping strategies including denial, withdrawal, and wishful thinking as responses to a stressor46.

Hence, a disengaging coping strategy can often result in inappropriate responses to stressors and in this light it seems plausible that high genetic liability to neuroticism was associated

with being placed in one of the elevated _loneliness_ trajectories. High PGS’s for psychiatric disorders were associated with the _high loneliness_ trajectory; hence, the increased

experience of loneliness in this trajectory could be explained by poor mental health, which is supported by the high prevalence of pre-pandemic psychiatric disorders in this trajectory.

Thus, it is not unlikely that poor mental health could result in less energy to establish and maintain a strong and supportive social network, especially in a pandemic setting with imposed

lockdowns. This pattern may also be further reinforced by the low PGS for the ‘big five’ personality trait extraversion associated with this trajectory, as extraversion often is described by

facets such as being active, assertive, energetic, enthusiastic, outgoing, and talkative47. Low PGS for the ‘big five’ personality traits agreeableness and conscientiousness were associated

with the _pandemic loneliness_ trajectory. Agreeableness characterises an individual’s degree of trust in others, straightforwardness, altruism, social compliance, modesty, and

tender-mindedness48. Hence, this personality trait is highly related to social interaction as it influences both self-image, social attitude, and life philosophy48. In this perspective, it

seems plausible that individuals with low genetic liability for agreeableness experienced more loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic, as they may have been less compliant and flexible to

shifting social norms including imposed lockdowns. Additionally, it has previously been demonstrated that low scores on conscientiousness combined with high scores on neuroticism were

associated with higher exposure to stress and strain, and a lower degree of problem-focused and engaging coping strategies49. Finally, the _pandemic loneliness_ trajectory had high PGS for

religious participation, potentially reflecting a vulnerability to loneliness when deprived of the social bonds usually maintained through religious practice. Research has shown that

individuals who partake in active religious practice are happier than those who are inactive or not affiliated50. On this background, it seems likely that individuals with high PGS for

religious participation would have had an increase in loneliness when deprived of religious participation and its associated social environment during the pandemic lockdowns. The overall

moderate correlation between loneliness and depression observed in the present study aligns with previous research highlighting the strong relationship between the phenomena. Interestingly,

the correlation remained stable during the pandemic’s height (December 2020) and midpoint (August 2021) but increased markedly by May 2022, when most pandemic restrictions were lifted in

Denmark. This could reflect that other factors such as social restrictions and lockdowns had a larger impact on levels of loneliness during the pandemic, but once these restrictions were

lifted, other personal factors such as symptoms of depression became more important for the experienced level of loneliness. Hence, individuals who remained lonely post-pandemic may

represent a particularly vulnerable subgroup (i.e., members of the _high loneliness_ trajectory), contributing to the stronger correlation observed during this period. This explanation is

also consistent with the stable levels of depression symptoms observed in each trajectory. While the _high loneliness_ trajectory remained high in both loneliness and depression symptoms at

the end of the pandemic when the correlation increased, the _pandemic loneliness_ trajectory decreased their level of loneliness at this point. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS Several strengths of

this study deserve mention. Firstly, the large study population provided increased statistical power and reduced random errors. Secondly, our measure of loneliness was sensitive to changes

in social restriction index (a macro level factor expected to impact on loneliness), indicating that UCLA-3 is sensitive to shifting norms over time. Thirdly, the multiple follow-up design

allowed prospective assessment of the same individuals over time enabling assessment of changes and lowering risk of bias related to cohort effects. Finally, we included a broad range of

both genetic, demographic, and socioeconomic factors allowing thorough descriptions of each identified trajectory. However, information on psychiatric diagnoses and psychotropic medication

was only available from 1995 and onwards, potentially resulting in misclassification. For the trajectory analysis it was required that participants had responded to all three questionnaires,

this may have resulted in lower functioning individuals to be excluded, although this not is a major concern as the attrition analysis showed very small difference between individuals with

three and individuals with less than three responses. In addition, the study was conducted among recurrent blood donors who are known to be healthier than the general population and reflect

differing underlying demographic properties51. The skew towards middle-aged and older adults, with limited representation of younger individuals restricts the scope of conclusions about

loneliness trajectories in younger populations and highlights an important direction for future research. Thus, the identified impact of social restrictions might be lower than in the

general population and the findings from the study may not be generalisable to other cohorts. Finally, estimation of loneliness prior to the pandemic was based on a retrospective measure

obtained during the pandemic, which could result in differential recall. Moreover, differential misclassification could also exist if individuals scoring high on e.g. neuroticism were more

likely to report higher levels of loneliness than individuals scoring low on neuroticism. CONCLUSIONS The present study showed that the nationwide restriction levels related to the COVID-19

pandemic had a clear overall effect on levels of loneliness, with particular vulnerability for females at the height of social restriction measures. Trajectories of loneliness during the

COVID-19 pandemic were characterised by different demographic and polygenic profiles, relevant for interventions against loneliness. Hence, this study consistently showed that the

individuals most severely impacted by social restrictions during the pandemic were already vulnerable to mental illness and had a personality composition allowing for tailored focus and

intervention. Based on these findings, prevention of loneliness should target individuals with low mental wellbeing, as this was the best indicator of liability to general loneliness and

loneliness in a pandemic setting and thus likely applicable in other macro-level scenarios beyond disease pandemics and associated societal restrictions. DATA AVAILABILITY Person-level data

from DBDS needed to reproduce this study cannot be made publicly available due to confidentiality legislation. Meta-data and programs are available from the authors upon reasonable request

and with permission of the DBDS steering committee, the Ethical Committee, and the Danish Data Protection Agency. Enquiries about legal possibilities for accessing these data within DBDS,

scripts/codes and further information should be addressed to the corresponding author. REFERENCES * Luhmann, M., Buecker, S. & Rüsberg, M. Loneliness across time and space. _Nat. Rev.

Psychol._ 2, 9–23 (2023). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Pengpid, S. & Peltzer, K. Associations of loneliness with poor physical health, poor mental health and health risk behaviours

among a nationally representative community-dwelling sample of middle-aged and older adults in India. _Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry_ 36, 1722–1731 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Griffin, S. C., Williams, A. B., Ravyts, S. G., Mladen, S. N. & Rybarczyk, B. D. Loneliness and sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. _Health Psychol. Open_ 7,

2055102920913235 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Park, C. et al. The Effect of Loneliness on Distinct Health Outcomes: A Comprehensive Review and Meta-Analysis.

_Psychiatry Res._ 294, 113514 (2020). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mann, F. et al. Loneliness and the onset of new mental health problems in the general population. _Soc. Psychiatry

Psychiatr. Epidemiol._ 57, 2161–2178 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Elovainio, M. et al. Association of social isolation, loneliness and genetic risk with

incidence of dementia: UK Biobank Cohort Study. _BMJ Open_ 12, e053936 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Andreu-Bernabeu, Á. et al. Polygenic contribution to the

relationship of loneliness and social isolation with schizophrenia. _Nat. Commun._ 13, 51 (2022). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rødevand, L. et al. Polygenic

overlap and shared genetic loci between loneliness, severe mental disorders, and cardiovascular disease risk factors suggest shared molecular mechanisms. _Transl. Psychiatry_ 11, 3 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Abdellaoui, A. et al. Predicting loneliness with polygenic scores of social, psychological and psychiatric traits. _Genes Brain Behav._ 17,

e12472 (2018). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Buecker, S., Maes, M., Denissen, J. J. A. & Luhmann, M. Loneliness and the Big Five Personality Traits: A Meta-Analysis. _Eur. J.

Pers._ 34, 8–28 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Domènech-Abella, J. et al. The association between socioeconomic status and depression among older adults in Finland, Poland and Spain: A

comparative cross-sectional study of distinct measures and pathways. _J. Affect. Disord._ 241, 311–318 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mushtaq, R., Shoib, S., Shah, T. &

Mushtaq, S. Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health ? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. _J. Clin. Diagn. Res._ 8, WE01–WE04 (2014).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Maes, M., Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Van den Noortgate, W. & Goossens, L. Gender differences in loneliness across the lifespan: A meta-analysis.

_Eur. J. Pers._ 33, 642–654 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Singh, A. & Misra, N. Loneliness, depression and sociability in old age. _Ind. Psychiatry J._ 18, 51–55 (2009). Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Buecker, S., Mund, M., Chwastek, S., Sostmann, M. & Luhmann, M. Is loneliness in emerging adults increasing over time? A preregistered

cross-temporal meta-analysis and systematic review. _Psychol. Bull._ 147, 787–805 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Menec, V. H., Newall, N. E., Mackenzie, C. S., Shooshtari, S.

& Nowicki, S. Examining individual and geographic factors associated with social isolation and loneliness using Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) data. _PLoS ONE_ 14, e0211143

(2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wu, J., Zhang, J. & Fokkema, T. The micro-macro interplay of economic factors in late-life loneliness: Evidence from

Europe and China. _Front. Public Health_ 10, 968411 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Andrighetto, G. et al. Changes in social norms during the early stages of the

COVID-19 pandemic across 43 countries. _Nat. Commun._ 15, 1436 (2024). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Einav, M. & Margalit, M. Loneliness before and after

COVID-19: Sense of Coherence and Hope as Coping Mechanisms. _Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health._ https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20105840 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Dahlberg, L. Loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. _Aging Ment. Health_ 25, 1161–1164 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Ausín, B., González-Sanguino, C., Castellanos,

M. Á. & Muñoz, M. Gender-related differences in the psychological impact of confinement as a consequence of COVID-19 in Spain. _Indian J. Gend. Stud._ 30, 29–38 (2021). Article Google

Scholar * Usher, K., Durkin, J. & Bhullar, N. The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. _Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs._ 29, 315–318 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Mancini, A. D. Heterogeneous mental health consequences of COVID-19: Costs and benefits. _Psychol. Trauma_ 12, S15–S16 (2020). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Christoffersen,

L. A. et al. Experience of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study of 50 968 adult Danes. _BMJ Open_ 13, e064033 (2023). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Bu, F.,

Steptoe, A. & Fancourt, D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. _Public Health_ 186, 31–34 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * McGinty, E. E., Presskreischer, R., Han, H. & Barry, C. L. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US Adults in 2018 and April 2020.

_JAMA_ 324, 93–94 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Luchetti, M. et al. The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. _Am. Psychol._ 75, 897–908 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Erikstrup, C. et al. Cohort Profile: The Danish Blood Donor Study. _Int. J. Epidemiol._ 52, e162–e171 (2023). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Hale, T. et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). _Nat. Hum. Behav._ 5, 529–538 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar

* Pedersen, C. B. The Danish Civil Registration System. _Scand. J. Public Health_ 39, 22–25 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Lynge, E., Sandegaard, J. L. & Rebolj, M. The

Danish National Patient Register. _Scand. J. Public Health_ 39, 30–33 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kessing, L. V., Ziersen, S. C., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E. & Andersen, P.

K. Lifetime Incidence of Treated Mental Health Disorders and Psychotropic Drug Prescriptions and Associated Socioeconomic Functioning. _JAMA Psychiat._ 80, 1000–1008 (2023). Article Google

Scholar * Pottegård, A. et al. Data Resource Profile: The Danish National Prescription Registry. _Int. J. Epidemiol._ 46, 798–798f (2017). PubMed Google Scholar * Hughes, M. E., Waite, L.

J., Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys: Results From Two Population-Based Studies. _Res. Aging_ 26, 655–672 (2004). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Russell, D., Peplau, L. A. & Cutrona, C. E. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. _J. Pers. Soc. Psychol._

39, 472–480 (1980). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Reliability and validity of the Danish version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (2007). Pers. Individ. Dif. _42_, 1359–1366. *

Steptoe, A., Shankar, A., Demakakos, P. & Wardle, J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A_ 110, 5797–5801 (2013).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hennig, C. Cluster Stability, Cluster Validation, and the Principle of Asymmetry in Cluster Analysis. (2005). * Maechler, M.,

Rousseeuw, P., Struyf, A., and Hubert, M. cluster: “Finding Groups in Data”: Cluster Analysis Extended Rousseeuw et al. (The R Foundation).

https://doi.org/10.32614/cran.package.clusterhttps://doi.org/10.32614/cran.package.cluster. (1999). * Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., and Williams, J.B.W.. Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

(American Psychological Association (APA)). https://doi.org/10.1037/t06165-000https://doi.org/10.1037/t06165-000. (2011). * Website RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R.

RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/. (2020). * Kendler, K. S., Thornton, L. M. & Prescott, C. A. Gender differences in the rates of exposure to stressful life events and

sensitivity to their depressogenic effects. _Am. J. Psychiatry_ 158, 587–593 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wilson, J., Demou, E. & Kromydas, T. COVID-19 lockdowns and

working women’s mental health: Does motherhood and size of workplace matter? A comparative analysis using understanding society. _Soc. Sci. Med._ 340, 116418 (2024). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Almeida, M., Shrestha, A. D., Stojanac, D. & Miller, L. J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s mental health. _Arch. Womens. Ment. Health_ 23, 741–748 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sediri, S. et al. Women’s mental health: acute impact of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence. _Arch. Womens. Ment. Health_ 23, 749–756

(2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Carver, C. S. & Connor-Smith, J. Personality and coping. _Annu. Rev. Psychol._ 61, 679–704 (2010). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * McCrae, R. R. & John, O. P. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. _J. Pers_ 60, 175–215 (1992). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Costa, P. T.

Jr., McCrae, R. R. & Dye, D. A. Facet scales for agreeableness and conscientiousness: A revision of the NEO personality inventory. _Pers. Individ. Dif._ 12, 887–898 (1991). Article

Google Scholar * Grant, S. & Langan-Fox, J. Occupational stress, coping and strain: The combined/interactive effect of the Big Five traits. _Pers. Individ. Dif._ 41, 719–732 (2006).

Article Google Scholar * Fahmy, D., Hackett, C., Marshall, J., Kramer, S., Schwadel, P., and Shi, A. Religion’s Relationship to Happiness, Civic Engagement and Health Around the World.

(2019). * Rigas, A. S. et al. The healthy donor effect impacts self-reported physical and mental health - results from the Danish Blood Donor Study (DBDS). _Transfus. Med._ 29(Suppl 1),

65–69 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank the psychiatric genetics consortium (https://pgc.unc.edu/) for providing summary statistics from

meta-GWAS, without Danish samples and Andrés Ingason, Joeri Meijsen, Mischa Lundberg, and Jesper Gådin, from the Institute for Biological Psychiatry for assisting with the data management of

these resources. The Authors would also like to thank the Danish blood donors for their valuable participation in the Danish Blood Donor Study as well as the staff at the blood centres

making this study possible. FUNDING This study received funding from NordForsk (project numbers 105668 and 138929) and from the EU Horizon REACT study (project number 101057129). Data was

collected during COVID-19 pandemic based on a grant from the Independent Research Fund Denmark (0214-00127B). The Danish Blood Donor Study’s biobank (Danish Blood Donor Biobank) is funded by

Bio- and Genome Bank Denmark. AJS was supported by a Lundbeck Foundation Fellowship (R335-2019–2318). The funding agents had no influence on study design, analyses, interpretation, or

publication. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Ole Birger Pedersen and Lea Arregui Nordahl Christoffersen. * A list of authors and their affiliations

appears at the end of the paper. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Clinical Immunology, Zealand University Hospital, Køge, Denmark Liam Quinn, Jakob Thaning Bay, Ole Birger Pedersen

& Lea Arregui Nordahl Christoffersen * Department of Clinical Immunology, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark Maria Didriksen, Christina Mikkelsen, Janna

Nissen, Khoa Manh Dinh & Sisse Rye Ostrowski * Department of Neuroscience, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark Maria Didriksen *

Department of Clinical Immunology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark Christian Erikstrup & Khoa Manh Dinh * Department of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

Christian Erikstrup * Department of Clinical Immunology, Aalborg University Hospital, Aalborg, Denmark Bitten Aagaard * Faculty of Health and Medical Science, Novo Nordisk Foundation Center

for Basic Metabolic Research, Copenhagen University, Copenhagen, Denmark Christina Mikkelsen * Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark Henrik Ullum * Clinical Immunology Research Unit,

Department of Clinical Immunology, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark Mie Topholm Bruun * Department of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of

Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark Sisse Rye Ostrowski & Ole Birger Pedersen * Institute of Biological Psychiatry, Mental Health Center St. Hans, Mental Health Services Copenhagen,

Roskilde, Denmark Thomas Werge, Andrew J. Schork & Lea Arregui Nordahl Christoffersen Authors * Liam Quinn View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Maria Didriksen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Christian Erikstrup View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Bitten Aagaard View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Christina Mikkelsen View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Henrik Ullum View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Janna Nissen View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jakob Thaning Bay View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Khoa Manh

Dinh View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mie Topholm Bruun View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Sisse Rye Ostrowski View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Thomas Werge View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Andrew J. Schork View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ole Birger Pedersen View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lea Arregui Nordahl Christoffersen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONSORTIA DBDS

GENETIC CONSORTIUM * Liam Quinn * , Maria Didriksen * , Christian Erikstrup * , Bitten Aagaard * , Christina Mikkelsen * , Henrik Ullum * , Janna Nissen * , Jakob Thaning Bay * , Khoa Manh

Dinh * , Mie Topholm Bruun * , Sisse Rye Ostrowski * , Thomas Werge * , Andrew J. Schork * , Ole Birger Pedersen * & Lea Arregui Nordahl Christoffersen CONTRIBUTIONS L.Q. and L.C. wrote

and prepared the manuscript text. L.Q., L.C., and O.B.P. devised the analyses and hypotheses. L.Q. carried out all analyses and prepared all the figures. All authors reviewed the

manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Liam Quinn. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICAL APPROVAL All procedures performed

in study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (The Zealand and Central Denmark Regional

Committees on Health Research Ethics [SJ-740 and 1–10-72–95-13] and the Data Protection Agency [P-2019–99]). Furthermore, genetic studies in the DBDS cohort were approved by the Danish

National Committee on Health Research Ethics (NVK-1700407). Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in the study. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature

remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and

reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you

modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in

this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative

Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a

copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Quinn, L., Didriksen, M., Erikstrup, C. _et al._

Nationwide longitudinal study reveals impact of both national restriction levels and genetic risk factors on loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. _Sci Rep_ 15, 17554 (2025).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02293-4 Download citation * Received: 08 January 2025 * Accepted: 13 May 2025 * Published: 20 May 2025 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02293-4

SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to

clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative