- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Instructional behavior plays a key role in learning motivation. In many developing countries, students’ learning motivation needs to be restored, primarily through effective

teaching. This research investigated the impact of instructional behaviors on learning motivation among high school students in Cambodia, emphasizing the mediating role of subjective task

value. This study was conducted in three provinces of Cambodia, and a sample was obtained by convenience sampling. A total of 515 participants (42.72% male and 56.70% female) were lower

secondary and high school students. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was applied to test the proposed relationship between the two first-order constructs of instructional behaviors and

learning motivation. The results revealed direct positive associations between all of the constructs in the model. Autonomy support was a significant predictor of both subjective task value

and intrinsic motivation. Cooperative learning support was significantly associated with only subjective task value and had no direct effect on intrinsic motivation. Conversely, video

lecture support positively predicted extrinsic motivation. Additionally, subjective task value played an important role as a mediator of the relationship between autonomy support and

cooperative learning support. These results emphasize the importance of developing instructional behaviors to support students’ learning motivation. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS

RESEARCH ON THE INFLUENCING FACTORS OF PROMOTING FLIPPED CLASSROOM TEACHING BASED ON THE INTEGRATED UTAUT MODEL AND LEARNING ENGAGEMENT THEORY Article Open access 02 July 2024 PUTTING ICAP

TO THE TEST: HOW TECHNOLOGY-ENHANCED LEARNING ACTIVITIES ARE RELATED TO COGNITIVE AND AFFECTIVE-MOTIVATIONAL LEARNING OUTCOMES IN HIGHER EDUCATION Article Open access 15 July 2024 LOOKING

BACK TO MOVE FORWARD: COMPARISON OF INSTRUCTORS’ AND UNDERGRADUATES’ RETROSPECTION ON THE EFFECTIVENESS OF ONLINE LEARNING USING THE NINE-OUTCOME INFLUENCING FACTORS Article Open access 09

May 2024 INTRODUCTION Flexible education to cope with difficult and restrictive situations is the most important thing to implement instantly1,2. Flexible education is able to rapidly help

face challenging times and tasks to restore the educational system, which increases the human capital linked to social needs and global trends3,4. The need- and trend-related education of

society plays a crucial role in achieving the economic goals of each country5. Developing countries are hindered by various obstacles more than developed countries are during difficult

times6,7. Hence, flexible education should be supervised simultaneously but this is difficult in developing countries8. The gap between developed and developing countries might be much

narrower if all stakeholders jointly concentrate and show resolve, especially concerning teacher instructional methods. Specifically, students’ educational outcomes are greatly affected by

teaching behavior through efficient instructional methods9. During and after the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries faced a lack of ample support for academic study10. Students experienced a

decline in academic motivation, potentially due to the rapid changes in learning contexts and formats brought by the pandemic11. Students with low learning motivation and those from

low-income families experienced the most hardships during the COVID-19 pandemic12. Students may lack the motivation to succeed in their studies if they do not perceive the value of learning

or if teachers fail to create an engaging and supportive learning environment13. Students will be pessimistic after learning without motivation. Motivation plays a crucial role in effective

learning, as it not only enhances academic performance but also promotes positive behavior and a fulfilling student experience. Understanding how to inspire children and young people to

learn is essential for providing them with the best foundation for success in life13. Conesa et al.14 conducted an analysis of the basic psychological needs of students in classrooms at the

elementary and secondary levels. The findings highlight the crucial role of teachers in addressing and supporting students’ psychological needs to foster an effective learning environment.

Many studies suggest that to promote learning motivation in various situations, including difficult times, flexible instructional behaviors may be appropriate1,11. Thus, teachers’ teaching

behavior is an important predictor of students’ academic motivation and positive learning outcomes. Therefore, teachers should adopt effective teaching strategies, such as autonomy

support15,16, video lecture support17, and cooperative learning18 to increase learners’ motivation, particularly in challenging educational contexts such as the recent COVID-19 pandemic and

in online courses19,20. Enhancing learning motivation among high school students requires effective teaching strategies that promote spontaneous engagement and intrinsic interest. According

to existing studies, one of the most effective teaching strategies is based on self-determination theory (SDT)21. To promote students’ intrinsic motivation, SDT highlights the importance of

meeting their core psychological demands for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Students’ willingness to study can be significantly increased by teachers who offer education that

encourages autonomy, cultivates a sense of cooperative learning, provides technologies for learning, and provides an environment that encourages students to use such technologies22. These

strategies work especially well for assisting high school students in managing their learning aspirations and encouraging sustained academic achievement. Learners who become accustomed to

support through that instructional behavior have higher intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Additionally, some studies have explored the role of instructional behaviors and digital

technologies in enhancing students’ learning motivation and academic outcomes23. These studies focus primarily on the direct impacts of instructional strategies and technological tools on

motivation. However, few studies have examined a comprehensive framework incorporating multiple instructional dimensions or investigating how instructional behaviors influence subjective

task value and intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. This is particularly the case with studies on subjective task value as a mediating variable. To address these gaps, this study

conceptualizes learning motivation by examining its relationship with instructional behaviors, specifically autonomy support, video lecture support, and cooperative learning. The aim is to

understand how these instructional behaviors contribute to shaping subjective task value and intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, which are key components of learning motivation. RATIONALE

AND RESEARCH OBJECTIVES Restoring students’ learning motivation after the COVID-19 pandemic should be considered a key focus in designing effective instructional strategies to prepare for

future crises. Previous studies have identified autonomy support as one of the strongest predictors of motivation15,16, although its influence may vary across different contexts, as shown in

prior research. Additionally, video lecture support24 and cooperative learning methods25,26 have been linked to enhanced learning motivation. In light of these findings, this research seeks

to address the following practical and effective research objectives. OBJECTIVES This study investigates the relationship between efficient instructional behavior and learning motivation

among school students in Cambodia. Specifically, it examines whether subjective task value mediates the effects of different dimensions of instructional behavior on learning motivation.

LITERATURE REVIEW LEARNING MOTIVATION Motivation theories break down motivation into intrinsic and extrinsic motivations and subjective task value. According to SDT27, intrinsic motivation

refers to whatever inspires people to learn or work internally, such as curiosity, self-competence, self-interest, and mastery learning. In contrast, extrinsic motivation refers to whatever

inspires people to learn or work externally, such as punishment, pressure, grades, self-expression, and other forms of persuasion27,28. When learners perceive intrinsic motivation, they

consistently endeavor to perform tasks and engage in learning procedures29. Intrinsic motivation encourages learners to engage in learning with enthusiasm, positive emotions, and

self-growth, primarily when supported by a growth mindset. It fosters more profound learning and self-regulation21,28. However, extrinsic motivation, such as rewards or recognition, is

essential to initiate engagement at the early stages- particularly for those without prior academic success. These external motivators can eventually be internalized, leading to more

autonomous learning. Therefore, effective education should balance both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to support learners throughout their development21. Grounded in expectancy-value

theory, subjective task value refers to a type of internal motivation driven by the degree of utility, attainment, and intrinsic value30. When learners perceive academic education, including

task value, they gain pleasure and usefulness and set an explicit goal for their future30. Chan et al.31 argued that learning motivation grounded in SDT is associated with subjective task

value grounding expectancy-value theory. Theorists also argue that when intrinsic value forms, intrinsic motivation is grown, whereas when attainment and utility value form, extrinsic

motivation is grown32. Several previous studies revealed that intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are associated with subjective task value33,34. EVT suggests that motivation depends on

students’ expectations of success and the value they place on tasks, including attainment, utility, intrinsic value, and cost30. In contrast, SDT emphasizes fulfilling psychological

needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—as the basis of motivation21. SDT is a precursor to EVT, as supportive environments that satisfy these needs help students build self-determined

motivation, enhancing their task value and success expectations. For instance, when teachers support autonomy and competence, students are more likely to believe in their abilities and value

their learning, linking both theories in a developmental sequence of motivational growth30,32. INSTRUCTIONAL BEHAVIORS Instructional behavior improves learners’ proficiency through

effective teaching methods23. Centered on previous studies and original theory, efficient instructional behaviors are divided into three categories: autonomy support, learning structure, and

involvement35. In this study, autonomy support refers to the extent to which teachers encourage students to take ownership of their learning by providing choices, fostering independence,

and supporting self-directed decision-making36. This conceptualization is rooted in SDT21, which defines autonomy as a core psychological need essential for intrinsic motivation. However,

within the framework of instructional behaviors, autonomy support specifically refers to teacher-driven strategies that promote student agency in learning environments, such as allowing

students to select assignments, choose group members, or express opinions about classroom activities37,38. Instructional autonomy support focuses on the external role of teachers in

facilitating student autonomy within structured educational settings39. Learning structure refers to how well teachers convey learning information through explicit instruction by encouraging

them to use follow-up learning strategies40. For example, learners might be motivated when offered explicit support through mechanical systems in the teaching methodology41. Video lecture

support is an influential learning structure that promotes student learning and engagement, and might be important teaching material for increasing classroom progress and for having

fascinating teaching techniques42. Videos linking clear textual and visual support tools encourage students to be motivated to learn and to be engaged through entire online and offline class

activities43,44. Despite growing interest in using videos to support instruction in learning, many schools in developing countries and vocational education sectors still have little

understanding of how different online video types or styles can facilitate student learning45. Learning involvement refers to the degree of self-connection between learners, as well as

between learners and teachers collaboratively in the learning process46. Previous studies have considered cooperative learning as a type of learning involvement47. Teachers’ consistent

involvement improve students’ social skills48. Previous studies have revealed that cooperative learning is the most important predictor of intrinsic motivation and subjective task value47.

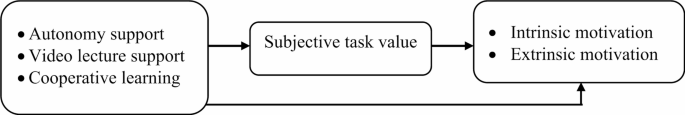

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK On the basis of the theoretical foundation and previous research discussed above, this study formulated the conceptual framework shown in Fig. 1. This research seeks to

fill gaps in existing research by investigating the effects of first-order constructs of instructional behaviors (autonomy support, video lecture support, and cooperative learning) on

first-order constructs of learning motivations (subjective task value, intrinsic motivation, and extrinsic motivation). Additionally, this study examines the moderating role of subjective

task value in these relationships. In the hypothetical model, this study initially assumed that effective instructional behaviors directly influence motivation based on established theories

and empirical evidence in educational psychology. Research in STD28,49 and EVT32 suggests that instructional behaviors directly impact students’ motivation. Studies have consistently

demonstrated that teacher behaviors that promote a positive learning environment, support student autonomy, and reinforce task value lead to increased motivation and engagement50. METHODS

PARTICIPANTS This study employed a quantitative cross-sectional research design. Convenience random sampling was used to select lower secondary and high school students from three provinces

in Cambodia. For this analysis, the participants consisted of a total of 515 students; 42.72% were male, and 56.70% were female. They had been studying in grades 8 (_n_ = 166, 32.23%), 9

(_n_ = 138, 26.80%), and 10 (_n_ = 211, 40.97%). The average age of the participants was 15.08 years (_SD_ = 1.08), ranging from 13 to 18 years. The sample size was determined by the rule of

thumb to select an appropriate sample size. According to previous research51, a suitable sample should consist of five to ten times the number of items in the research model. DATA

COLLECTION In support of this study, data were gathered through a survey of high school students in Cambodia by using a self-report questionnaire and were collected between 1 February and 28

February 2023. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the research ethics committee of the Royal University of Phnom Penh, Cambodia (136/2023 RUPPKS). A permission letter was

sent to the principals of the high schools to request collaboration. Students were free to withdraw their participation in the questionnaire at any time. The data collected from the

volunteer students were kept confidential, and only the research team had access to the data. The privacy and anonymity of the participants were maintained throughout the study period.

INSTRUMENTS LEARNING MOTIVATION SCALE To assess the students’ perceptions of learning motivation, the learning motivation questionnaire of Pintrich et al.52 was adapted for this study.

Pintrich’s Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) is designed to assess different aspects of student motivation and aligns closely with SDT, especially in how it

distinguishes between types of motivation. While SDT highlights the role of intrinsic motivation, which stems from fulfilling basic psychological needs, the MSLQ captures both intrinsic and

extrinsic motivation. This makes it a valuable tool for understanding students’ motivational experiences, often shaped by teaching practices and the learning environment. This instrument

consists of 16 items with three subscales (Table 1), namely, (a) subjective task value (six items, e.g., “I think the course material is useful for me to learn”), (b) intrinsic motivation

(five items, e.g., “I prefer course material that arouses my curiosity, even if it is difficult to learn”), and (c) extrinsic motivation (five items, e.g., “The most important thing for me

is improving my overall grade or grade point average”). The item scores were averaged to create a score for each aspect for each respondent. Higher scores indicated higher learning

motivation. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for subjective task value (0.73), intrinsic learning motivation (0.63), and extrinsic learning motivation (0.81) indicated good internal

consistency (Table 2). INSTRUCTIONAL BEHAVIOR SCALE The instructional behaviors scale was adapted from prior studies31,47,53. This measurement consists of 15 items that measure 3 components

(Table 1), including (a) teachers’ autonomy support (four items, e.g., “My teacher accepted my suggestions on how to do homework or exercises that I sought”), (b) teachers’ video lecture

support (six items, e.g., “The lesson was well explained in the video lecture”), and (c) cooperative learning support (five items, e.g., “When I did group work, I discussed my ideas with

other students in my group”). The Cronbach’s alpha values for autonomy support, video lecture support, and cooperative learning support were 0.72, 0.79, and 0.76, respectively, suggesting

acceptable internal consistency (Table 2). Both the learning motivation and instructional behavior questionnaires were self-reported measures, without reverse items included. The original

questionnaires were in English and were translated into Khmer using the back-translation technique by two bilingual Cambodian lecturers. After the scales were translated back into English,

we compared the Khmer and English versions of the scales to determine whether each item matched the initial meaning. The Khmer version of the scale was subsequently administered to 50 high

school students to evaluate each item’s appropriateness and face validity before the data were collected. For all the scales, the students were asked to rate each item on a 5-point Likert

scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The constructs, dimensions, and items used in this study are shown in Table 1. DATA ANALYSIS Prior to initiating data

analysis, the missing data for each variable included in this study were addressed as follows: (1) responses above 10% missing data were excluded from the study, and (2) variables with

missing data below 10%, the missing values were imputed using the observed mean of the corresponding variable. Preliminary analyses and descriptive statistics were used to describe and

summarize the data. Skewness and kurtosis values were checked for the normality of the data. Pearson correlation analysis was employed to assess the hypothesized relationships between the

variables. Before testing the hypothesized causal relationships, we assessed the construct validity of the measurement model using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA was performed to

validate a measurement model of each aspect of instructional behavior and learning motivation. The convergent validity of the measurement model was verified through average variance

extracted (AVE) values. Scale reliability was assessed through composite reliability (CR), Cronbach’s alpha (α), and McDonald’s omega coefficient. The discriminant validity of the constructs

was assessed via the heterotrait‒monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations, the square root of the AVE, the maximum shared variance (MSV), and the average shared variance (ASV). The accepted

level of discriminant validity is an HTMT value less than 0.9054, the square root of the AVE for each construct is higher than the correlation coefficient values of the other constructs

are51, and both the MSV and the ASV are lower than the AVE. The final analysis used structural equation modeling (SEM) with an MLR estimator to test the direct and indirect relationships

among the six constructs. The goodness of fit of the measurement model and the structural equation model was assessed by the following indices and cutoff criteria: chi-square per degrees of

freedom (_χ2/df_ ≤ 3), comparative fit index (CFI ≥ 0.90), Tucker‒Lewis index (TLI ≥ 0.90), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA ≤ 0.08), and standardized root mean square residual

(SRMR < 0.08)51,55,56,57,58. All performances were analyzed with Mplus 8.13 59, the JASP team, and R package software. In the final stage, an independent t-test was employed to compare

the mean scores between different groups. RESULTS PRELIMINARY ANALYSIS Descriptive statistics, including the mean (_M_), standard deviation (_SD_), skewness (_SK_), and kurtosis (_KU_),

coupled with α, are displayed in Table 2. This study’s _SK_ values were between − 0.523 and 0.263, and the _KU_ values were between 0.384 and 1.027, confirming the normality of the data. The

mean scores for autonomy support, video lecture support, cooperative learning support, subjective task value, intrinsic motivation, and extrinsic motivation were 3.471 (_SD_ = 0.664), 3.434

(_SD_ = 0.615), 3.948 (_SD_ = 0.465), 4.151 (_SD_ = 0.406), 3.934 (_SD_ = 0.437), and 3.773 (_SD_ = 0.630), respectively (Table 2). The results of the correlation analysis, as shown in

Table 3, indicated that all the correlations were significantly positive. The highest correlation was between subjective task value and intrinsic motivation (_r_ = 0.506, _p_ < 0.01),

whereas the lowest correlation was between video lecture support and subjective task value (_r_ = 0.161, _p_ < 0.01). CONFIRMATORY FACTOR ANALYSIS (CFA) During CFA, a second-order model

was established for both the instructional behavior scale and the learning motivation scale. The model fit indices met the required criteria, demonstrating the validity and reliability of

the second-order structure for these constructs in the Cambodian context. The acceptable model fit indices are as follows (Table 4): (a) instructional behavior scale, with χ²(77) = 188.377,

_χ²/df =_ 2.446, CFI = 0.943, TLI = 0.922, SRMR = 0.045, and RMSEA = 0.053 (90% CI: 0.043 to 0.063); and (b) learning motivation scale, with χ²(96) = 163.742, _χ²/df =_ 1.706, CFI = 0.964,

TLI = 0.955, SRMR = 0.039, and RMSEA = 0.037 (90% CI: 0.027 to 0.047). All standardized factor loading scores were statistically significant and ranged from 0.443 to 0.726 (_p_ < 0.01),

confirming that the observed variables are reliable indicators of their latent construct51. CONVERGENT VALIDITY AND DISCRIMINANT VALIDITY In this study, the convergent validity of the

measurement model was assessed by the AVE and CR. As shown in Table 5, the AVE values were greater than 0.50, which indicates that each construct is accurately measured by its items60.

Similarly, the CR scores for all the constructs ranged from 0.652 to 0.811, well above the benchmark of 0.70, indicating that the items used to measure the constructs have high

reliability51,56. Discriminant validity confirms that instruments designed to assess different constructs are independent and do not assess the same fundamental concept60. The HTMT value

(Table 3) and square root of the AVE for each construct were utilized to assess the discriminant validity of the measurement model. Discriminant validity was established for all the

constructs as the HTMT values (ranging from 0.192 to 0.761), and the intercorrelations of the constructs (ranging from 0.161 to 0.506) were less than 0.9054 (Table 3). The square root value

of the AVE of each construct (ranging from 0.523 to 0.681) was greater than its Pearson correlation coefficient with the other constructs. INTERNAL CONSISTENCY Cronbach’s alpha and

McDonald’s omega coefficients were used to measure the internal consistency of the multidimensional scale. As shown in Table 2, all the factors demonstrated acceptable internal consistency,

with both coefficients meeting or exceeding the threshold of 0.6061. The reliability results for each factor are as follows: autonomy support (α = 0.72, ω = 0.68), video lecture support (α =

0.79, ω = 0.78), cooperative learning support (α = 0.76, ω = 0.77), subjective task value (α = 0.73, ω = 0.73), intrinsic motivation (α = 0.63, ω = 0.62), and extrinsic motivation (α =

0.81, ω = 0.81). STRUCTURAL EQUATION MODELING (SEM) To investigate the causal relationship of the developed hypothesized structural model between instructional behaviors and learning

motivation, this study employed SEM. The analysis focused on the first-order constructs of both instructional behavior and learning motivation scales. However, after adjusting the model

according to the suggested modification indices, some paths identified as nonsignificant were not included, with the proposed model being a better-fitting model. As shown in Tables 4 and 6;

Fig. 2, the SEM results revealed an acceptable model fit, with _χ²_(417) = 822.996, _p_ < 0.001, _χ²/df_ = 1.974, CFI = 0.903, TLI = 0.891, RMSEA = 0.043 (90% CI: 0.039 to 0.048), and

SRMR = 0.051. The independent variables explained the proportion of variance in the endogenous latent variables as follows: subjective task value explained approximately 47.4% (_R_2 =

0.474), intrinsic motivation explained approximately 67.3% (_R__2_ = 0.673), and extrinsic motivation explained approximately 22.1% (_R_2 = 0.221). These findings indicate the robustness of

the SEM model, in which the independent variables can efficiently predict the variance in the endogenous latent variables. The standardized path coefficients for direct effects and indirect

effects can be summarized as follows: * (1) Regarding the direct effect, the SEM results revealed that the construct with the greatest significant positive effect on subjective task value

was cooperative learning support (_β_ = 0.616, _p_ < 0.01), followed by autonomy support (_β_ = 0.167, _p_ < 0.01), indicating that students who perceive that they receive good

cooperative learning support and autonomy support are more likely to have higher subjective task value. The results further demonstrated that subjective task value had the highest

standardized positive direct effect on intrinsic motivation (_β_ = 0.707, _p_ < 0.01), followed by autonomy support (_β_ = 0.231, _p_ < 0.01), suggesting that students who perceive

subjective task value and receive autonomy support tend to have greater intrinsic motivation to learn than others do. Furthermore, subjective task value (_β_ = 0.366, _p_ < 0.01) and

video lecture support (_β_ = 0.203, _p_ < 0.01) were positively linked to extrinsic motivation. This finding is surprising because the results showed that students who perceived

subjective task value and who had good-quality video lecture support were more likely to have extrinsic motivation, which means action driven by external rewards. In summary, subjective task

value was the only construct that promoted both intrinsic and intrinsic motivations among students in Cambodia. * (2) The indirect effects were analyzed to confirm that subjective task

value was a mediator of the relationship between instructional behaviors and motivation types. The findings from the mediation analysis revealed that cooperative learning support had the

greatest significant indirect effect on intrinsic motivation (_β_ = 0.436, _p_ < 0.01) and extrinsic motivation (_β_ = 0.226, _p_ < 0.01) via subjective task value. This finding means

that when students have better collaborative learning when working with groups, they have higher subjective task value, which affects their intrinsic motivation. Similarly, autonomy support

had strong mediating effects on intrinsic motivation (_β_ = 0.118, _p_ < 0.01) and extrinsic motivation (_β_ = 0.061, _p_ < 0.01). This finding demonstrates that when students perceive

autonomy in learning environments, they tend to develop a greater perception of subjective task value, which leads to an increase in their intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for learning.

However, video lecture support did not mediate through subjective task value, suggesting its limited role in fostering intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. RESULTS OF INDEPENDENT SAMPLES

T-TEST The independent samples t-test results (Table 7) showed significant differences (_p_ < 0.01) in perceived instructional behavior, with high school students reporting significantly

better perceptions than junior high school students in all three dimensions: autonomy support, video lecture support, and cooperative learning support. When considering the sub-items, the

items in which the perceptions of the two groups were not statistically different were AS1, AS2 and SC1 (_p_ > 0.01). DISCUSSION This study investigated how efficient instructional

behaviors may be related to student learning motivation using structural equation modeling (SEM) to explore these associations. The SEM findings supported hypothesized relationships by

demonstrating that most instructional activities were directly or indirectly associated with endogenous variables. The study revealed that most instructional behaviors might be associated

with all endogenous variables. Subjective task value was directly associated with cooperative learning support. It is more likely that students perceive cooperative learning as an

opportunity to engage in meaningful interactions, share ideas during group discussions, and receive teacher-led training in social skills. These experiences ensure that they work positively

and accountably with their peers, fostering a sense of responsibility and collaboration. Such an environment may also enhance students connect learning tasks to their interests, set future

goals, and recognize the intrinsic value of education in enhancing their competence and achieving academic success. This aligns with research emphasizing the importance of collaborative

environments in enhancing task value and student engagement (Johnson & Johnson, 2014; Slavin, 2015). Teachers train students in social skills to ensure that they work positively and

accountably during class through positive interactions between peers. This is a reason to attract students to match what they learn, link their interests, set goals for the future, and

understand the value that all learning is important for their competence and academic results62. Although cooperative learning support was not directly linked to extrinsic motivation or

intrinsic motivation, it appeared to have a significant indirect effect on both dimensions of motivation through subjective task value as a mediating variable. This finding may reflect the

hesitation of some students to fully engage during group work, as previously reported by Moon and Ke37. The findings suggest that although cooperative learning promotes task valuation, it

may not always directly into increased individual motivation, which may be due to different levels of cooperation or cultural and contextual factors that affect group dynamics. However,

well-implemented cooperative learning may increase students’ motivation to learn. Video lecture support was directly associated only with extrinsic motivation, and it was not significantly

related to subjective task value or intrinsic motivation, which are important variables for predicting extrinsic motivation. This finding may be explained by students’ perceptions that video

lessons provide sufficient support for external needs, such as improving grades or meeting external expectations while alleviating the pressure of comprehension challenges. The results

align with those of prior studies indicating that video-based instruction supports performance-oriented outcomes and sustains interest42,53. However, the lack of effect on intrinsic

motivation or subjective task value indicates that video-based lecture support may lack the interactivity and engagement needed to inspire deeper self-awareness. This reflects the importance

of video-based content design that should enhance learner-interactive formats and that content and presentation should engage learners in reflective and meaningful tasks that will motivate

them to learn and work in the future24. Autonomy support was found to be the strongest predictor of intrinsic motivation and subjective task value. Encouraging independence makes children

feel happier and more valued while learning, which is more valuable for children’s growth than rewards are. These findings are consistent with SDT, which hypothesizes that autonomy enhances

intrinsic motivation by fostering a sense of choice and ownership over learning tasks21. Teachers who support decision-making and provide opportunities for self-directed learning help

learners align their goals with the perceived importance and usefulness of their studies. Such alignment increases intrinsic motivation, leading to curiosity, competence, mastery learning,

and sustained academic engagement. These findings corroborate those of previous studies that emphasized the important role of autonomy support in promoting both motivation and academic

success37,38. Subjective task value also played an important role in predicting both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. In this sense, the valuation of self-enjoyment, learning usefulness,

and future career goal-related learning might impact how well students’ perceptions increase their curiosity, mastery learning, and self-competence, and it might encourage them to meet

externally related requirements set by others that are necessary during academic education, such as grades, rewards, and self-expression63. As asserted by previous studies31, students might

be intrinsically and extrinsically motivated when they value what they learn or do to complete a learning task. The analysis of indirect effects further revealed that cooperative learning

support and autonomy support were significantly associated with intrinsic and extrinsic motivations through the mediating role of subjective task value. These findings highlight the

importance of subjective task value in instructional behaviors, aligning with prior studies that identified task value as a critical component for fostering motivation30,64. When students

perceive cooperative and autonomous support as sufficient, they are more likely to value their learning, connect it with future goals, and develop self-regulatory capabilities. This

highlights the need for educators to design instructional strategies that simultaneously promote autonomy, collaboration, and task value to achieve comprehensive motivational outcomes.

However, contrary to expectations, the SEM results in this study found that some expected relationships were nonsignificant, particularly the mediating role of subjective task value in video

lecture support and motivation types. Video lecture support did not significantly mediate through subjective task value. This may be due to students’ passive engagement with video-based

materials. Research by Brame65 and Galatsopoulou et al.66 has suggested that video lectures are most effective when students are actively engaged through interactive elements, such as

discussions or problem-solving tasks. If students in Cambodia primarily consume video lectures as a one-way delivery of content rather than an interactive experience, this could explain why

video lecture support did not strongly influence intrinsic or extrinsic motivation through subjective task value. Additionally, Cambodia’s social and educational environment may play a role

in these findings. Studies on Southeast Asian educational contexts (e.g., Sariani et al.67 highlight that traditional teacher-centered methods are still dominant, with limited self-regulated

and technology-enhanced learning integration. If students are not accustomed to leveraging video lectures for deep learning, their subjective task value for such instructional materials may

be lower than expected, resulting in a weak mediation effect. Moreover, external factors such as limited access to high-quality digital resources and variations in technological

infrastructure could further explain the weaker role of video lecture support in fostering motivation. The findings support the notion that instructional behaviors may influence motivation,

mainly through enhancing task value23, which aligns with SDT’s focus on intrinsic motivation and Pintrich’s view of task value as a key predictor of motivation. This integrated model extends

the theoretical understanding of how teacher behaviors can create an environment that fosters intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, suggesting that motivation is not a unidimensional

construct but a complex interplay of multiple factors. Additionally, this study contributes to the literature by demonstrating how integrating SDT and Pintrich’s framework can provide a more

comprehensive explanation of motivation in educational contexts. The model developed here can be used as a basis for future studies to explore further the interactions between instructional

behaviors, student motivation, and academic engagement. FUTURE RESEARCH AND LIMITATIONS This study focused on secondary and high school students, with a limited sample size that did not

represent all regions of Cambodia. Future research should include university students and expand the sample size to increase the generalizability of the findings. Another limitation of this

study is its reliance on a cross-sectional approach. Future studies could adopt longitudinal designs to explore the progression of teachers’ instructional practices and students’ motivation

over time or conduct multigroup analyses to examine whether the theoretical model holds across different samples. Moreover, this study did not consider environmental factors such as school

policies, school types, or student socioeconomic status, which may influence learning motivation. Future research should incorporate these factors and explore their impact. The use of

qualitative methods could also provide deeper insights into the complexities of educational management, teaching practices, and student motivation. CONCLUSION This study sought efficient

instructional behavior to address learning motivation issues after the end of the COVID-19 pandemic in Cambodia. Interestingly, this study reveals efficient instructional behavior, which has

three points. First, teachers should provide autonomy support that allows students to make their own decisions through their choices with their learning tasks, group work, and groupmates.

Second, the teacher should provide video lecture support linked with students’ interests, be helpful in learning and working on their tasks, provide clear explanations, and make connections

with in-class activities. Third, teachers should provide cooperative learning support, such as peer support, peer feedback, and peer teaching, through the responsibility of groups to share

their ideas among peers. In summary, further implications might be considered in terms of general education. DATA AVAILABILITY The original data are available on reasonable request from the

corresponding author. REFERENCES * Srinivasan, S., Ramos, J. A. L. & Muhammad, N. A. Flexible future education Model—Strategies drawn from teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. _Educ.

Sci._ 11, 557. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci1109055 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Morris, J. E. & Imms, W. Flexible furniture to support inclusive education: developing learner

agency and engagement in primary school. _Learn. Environ. Res._ https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-024-09522-z (2024). Article Google Scholar * Wanke, P., Lauro, A., dos Santos Figueiredo, O.

H., Faria, J. R. & Mixon, F. G. The impact of school infrastructure and teachers’ human capital on academic performance in Brazil. _Eval. Rev._ 48, 636–662.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841x231197741 (2024). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Vadeboncoeur, J. A. & Padilla-Petry, P. Learning from teaching in alternative and flexible education

settings. _Teach. Educ._ 28, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1265928 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Mulenga, I. M. & Chileshe, E. Appropriateness and adequacy of teaching

and learning resources and students’ industrial attachment in public colleges of technical and vocational education in Zambia. _East. Afr. J. Educ. Social Sci._ 1, 30–42.

https://doi.org/10.46606/eajess2020v01i02.0019 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Khampirat, B., Na Ayudhaya, H. & Bamrungsin, P. N. in _From pedagogy to quality assurance in education:

an international perspective_. (ed _Flavian Heidi)_ 129–153 (Emerald, 2020). * Mishkin, F. S. _Understanding Financial Crises: A Developing Country Perspective_ (National Bureau of Economic

Research, 1996). * Khampirat, B. The relationship between paternal education, self-esteem, resilience, future orientation, and career aspirations. _PloS One_. 15, e0243283–e0243283.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243283 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Civitillo, S., Mayer, A. M. & Jugert, P. A systematic review and

meta-analysis of the associations between perceived teacher-based racial–ethnic discrimination and student well-being and academic outcomes. _J. Educ. Psychol._ 116, 719–741.

https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000818 (2024). Article Google Scholar * Grewenig, E., Lergetporer, P., Werner, K., Woessmann, L. & Zierow, L. COVID-19 and educational inequality: how

school closures affect low- and high-achieving students. _Eur. Econ. Rev._ 140, 103920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2021.103920 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Pelikan, E. R. et al. Distance learning in higher education during COVID-19: the role of basic psychological needs and intrinsic motivation for persistence and procrastination–a

multi-country study. _PLOS ONE_. 16, e0257346. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tadesse, S. & Muluye, W. The

impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education system in developing countries: A review. _Open. J. Social Sci._ 8, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.810011 (2020). Article Google Scholar

* Feng, Z. & Xiao, H. The impact of students’ lack of learning motivation and teachers’ teaching methods on innovation resistance in the context of big data. _Learn. Motiv._ 87,

102020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2024.102020 (2024). Article Google Scholar * Conesa, P. J., Onandia-Hinchado, I., Duñabeitia, J. A. & Moreno, M. Á. Basic psychological needs in

the classroom: A literature review in elementary and middle school students. _Learning and Motivation_ 79, 101819, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2022.101819 * Mammadov, S. &

Schroeder, K. A meta-analytic review of the relationships between autonomy support and positive learning outcomes. _Contemp. Educ. Psychol._ 75, 102235.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2023.102235 (2023). Article Google Scholar * Behzadnia, B., Mohammadzadeh, H. & Ahmadi, M. Autonomy-supportive behaviors promote autonomous

motivation, knowledge structures, motor skills learning and performance in physical education. _Curr. Psychol._ 38, 1692–1705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9727-0 (2019). Article

Google Scholar * Liao, C. H. & Wu, J. Y. Learning analytics on video-viewing engagement in a flipped statistics course: relating external video-viewing patterns to internal motivational

dynamics and performance. _Comput. Educ._ 197, 104754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104754 (2023). Article Google Scholar * Bećirović, S., Dubravac, V. & Brdarević-Čeljo, A.

Cooperative learning as a pathway to strengthening motivation and improving achievement in an EFL classroom. _Sage Open._ 12, 21582440221078016. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221078016

(2022). Article Google Scholar * Bamrungsin, P. & Khampirat, B. Improving professional skills of pre-service teachers using online training: applying work-integrated learning

approaches through a quasi-experimental study. _Sustainability_ 14, 4362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074362 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Usher, E. L. et al. Psychology students’

motivation and learning in response to the shift to remote instruction during COVID-19. _Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. Psychol._ 10, 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000256 (2024). Article

Google Scholar * Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions.

_Contemp. Educ. Psychol._ 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Susanti, A., Rachmajanti, S. & Mustofa, A. Between teacher’ roles

and students’ social: learner autonomy in online learning for EFL students during the pandemic. _Cogent Educ._ 10, 2204698. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2204698 (2023). Article

Google Scholar * Maulana, R., Opdenakker, M. C. & Bosker, R. Teachers’ instructional behaviors as important predictors of academic motivation: changes and links across the school year.

_Learn. Individual Differences_. 50, 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.07.019 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Zainuddin, Z. Students’ learning performance and perceived

motivation in gamified flipped-class instruction. _Comput. Educ._ 126, 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.003 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Chen, B. Influence of

cooperative learning on learners’ motivation: the case of Shenzhen primary school. _Educ. 3–13_. 51, 647–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2021.1998179 (2023). Article Google Scholar *

Filippou, D., Buchs, C., Quiamzade, A. & Pulfrey, C. Understanding motivation for implementing cooperative learning methods: A value-based approach. _Soc. Psychol. Educ._ 25, 169–208.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-021-09666-3 (2022). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation,

social development, and well-being. _Am. Psychol._ 55, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.1.68 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L.

_Self-determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness_ (The Guilford Press, 2017). * Wulf, G. & Lewthwaite, R. Optimizing performance through

intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: the OPTIMAL theory of motor learning. _Psychon. Bull. Rev._ 23, 1382–1414. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0999-9 (2016). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Eccles, J. S., O’Neill, S. A. & Wigfield, A. in _What do children need to flourish: Conceptualizing and measuring indicators of positive development. The Search

Institute series on developmentally attentive community and society._ 237–249Springer Science, (2005). * Chan, S., Maneewan, S. & Koul, R. An examination of the relationship between the

perceived instructional behaviours of teacher educators and pre-service teachers’ learning motivation and teaching self-efficacy. _Educational Rev._ 75, 264–286.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1916440 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Wigfield, A. & Eccles, J. S. Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. _Contemp. Educ. Psychol._

25, 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Husman, J., Derryberry, W. P. & Crowson, H. M. Instrumentality, task value, and

intrinsic motivation: making sense of their independent interdependence. _Contemp. Educ. Psychol._ 29, 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-476X(03)00019-5 (2004). Article Google Scholar *

Vanslambrouck, S., Zhu, C., Lombaerts, K., Philipsen, B. & Tondeur, J. Students’ motivation and subjective task value of participating in online and blended learning environments.

_Internet High. Educ._ 36, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.09.002 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Hornstra, L., Stroet, K. & Weijers, D. Profiles of teachers’

need-support: how do autonomy support, structure, and involvement cohere and predict motivation and learning outcomes? _Teach. Teacher Educ._ 99, 103257.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103257 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Zhou, L. H., Ntoumanis, N. & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. Effects of perceived autonomy support from social agents

on motivation and engagement of Chinese primary school students: psychological need satisfaction as mediator. _Contemp. Educ. Psychol._ 58, 323–330.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.05.001 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Moon, J. & Ke, F. Exploring the relationships among middle school students’ peer interactions, task

efficiency, and learning engagement in game-based learning. _Simul. Gaming_. 51, 310–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878120907940 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Patall, E. A. &

Zambrano, J. Facilitating student outcomes by supporting autonomy: implications for practice and policy. _Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci._ 6, 115–122.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732219862572 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Lietaert, S., Roorda, D., Laevers, F., Verschueren, K. & De Fraine, B. The gender gap in student engagement:

the role of teachers’ autonomy support, structure, and involvement. _Br. J. Educ. Psychol._ 85, 498–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12095 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Jang,

H., Reeve, J. & Deci, E. Engaging students in learning activities: it is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. _J. Educ. Psychol._ 102, 588–600.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019682 (2010). Article Google Scholar * Chan, S., Maneewan, S. & Koul, R. An examination of the relationship between the perceived instructional behaviours of

teacher educators and pre-service teachers’ learning motivation and teaching self-efficacy. _Educational Rev._ 75, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1916440 (2021). Article

Google Scholar * Sablić, M., Mirosavljević, A. & Škugor, A. Video-Based learning (VBL)—Past, present and future: an overview of the research published from 2008 to 2019. _Technol.

Knowl. Learn._ 26, 1061–1077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-020-09455-5 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Bennett, K. D., Aljehany, M. S. & Altaf, E. M. Systematic review of

video-based instruction component and parametric analyses. _J. Special Educ. Technol._ 32, 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162643417690255 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Chen, Y. C., Lu,

Y. L. & Lien, C. J. Learning environments with different levels of technological engagement: a comparison of game-based, video-based, and traditional instruction on students’ learning.

_Interact. Learn. Environ._ 29, 1363–1379. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1628781 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Arkenback, C. YouTube as a site for vocational learning:

instructional video types for interactive service work in retail. _J. Vocat. Educ. Train._ 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2023.2180423 (2023). * Chiu, T. K. F. Applying the

self-determination theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. _J. Res. Technol. Educ._ 54, S14–S30.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1891998 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Chan, S., Maneewan, S. & Koul, R. Cooperative learning in teacher education: its effects on EFL

pre-service teachers’ content knowledge and teaching self-efficacy. _J. Educ. Teach._ 47, 654–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2021.1931060 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Le, H.,

Janssen, J. & Wubbels, T. Collaborative learning practices: teacher and student perceived Obstacles to effective student collaboration. _Camb. J. Educ._ 48, 103–122.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2016.1259389 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. The what and why of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of

behavior. _Psychol. Inq._ 11, 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 (2000). Article Google Scholar * Reeve, J. & Cheon, S. H. Autonomy-supportive teaching: its

malleability, benefits, and potential to improve educational practice. _Educational Psychol._ 56, 54–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2020.1862657 (2021). Article Google Scholar *

Hair, J., Black, J. F., Babin, W. C., Anderson, R. E. & B. J. & _Multivariate Data Analysis_ 7th edn (Pearson, 2014). * Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A., Garcia, T. & McKeachie, W.

J. _A Manual for the Use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ)_ (University of Michigan, 1991). * Long, T., Logan, J. & Waugh, M. Students’ perceptions of the

value of using videos as a pre-class learning experience in the flipped classroom. _TechTrends_ 60, 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0045-4 (2016). Article Google Scholar *

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. _J. Acad. Mark. Sci._ 43, 115–135.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional

criteria versus new alternatives. _Struct. Equ. Model._ 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999). Article Google Scholar * Kline, R. B. _Principles and Practice of

Structural Equation Modeling_ (Guilford Press, 2011). * McNeish, D. & Wolf, M. G. Dynamic fit index cutoffs for confirmatory factor analysis models. _Psychol. Methods_. 28, 61–88.

https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000425 (2023). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Shi, D., Lee, T. & Maydeu-Olivares, A. Understanding the model size effect on SEM fit indices. _Educ.

Psychol. Meas._ 79, 310–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164418783530 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. _Mplus: the Comprehensive Modeling Program

for Applied Researchers User’s Guide, Version 3.13_ (Muthén & Muthén, 2005). * Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and

measurement error. _J. Mark. Res._ 18, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312 (1981). Article Google Scholar * van Griethuijsen, R. A. L. F. et al. Global patterns in students’ views of

science and interest in science. _Res. Sci. Educ._ 45, 581–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-014-9438-6 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Hank, C. & Huber, C. Do peers influence the

development of individuals’ social skills? The potential of cooperative learning and social learning in elementary schools. _Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol._ 9, 747–773.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00151-8 (2024). Article Google Scholar * Hayat, A. A., Shateri, K., Amini, M. & Shokrpour, N. Relationships between academic self-efficacy,

learning-related emotions, and metacognitive learning strategies with academic performance in medical students: a structural equation model. _BMC Med. Educ._ 20, 76.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-01995-9 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Part, R., Perera, H. N., Marchand, G. C. & Bernacki, M. L. Revisiting the

dimensionality of subjective task value: towards clarification of competing perspectives. _Contemp. Educ. Psychol._ 62, 101875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101875 (2020). Article

Google Scholar * Brame, C. J. Effective educational videos: principles and guidelines for maximizing student learning from video content. _CBE Life Sci. Educ._ 15

https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-03-0125 (2016). * Galatsopoulou, F., Kenterelidou, C., Kotsakis, R. & Matsiola, M. Examining students’ perceptions towards video-based and video-assisted

active learning scenarios in journalism and communication courses. _Educ. Sci._ 12, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020074 (2022). Article Google Scholar * Sariani, Miladiyenti, F.,

Rozi, F., Haslina, W. & Marzuki, D. Incorporating mobile-based artificial intelligence to english pronunciation learning in tertiary-level students: developing autonomous learning. _Int.

J. Adv. Sci. Comput. Eng._ 4, 220–232. https://doi.org/10.62527/ijasce.4.3.92 (2022). Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was funded by the National

Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) via the Program Management Unit for Human Resources and Institutional Development, Research, and Innovation (grant number B05F640220); and was

supported by (i) Suranaree University of Technology (SUT), (ii) Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI), and (iii) National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) (NRIIS number

204202 and project code 90464; and NRIIS number 195583). AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Kandal Regional Teacher Training Center (RTTC), Kandal, Cambodia Daro Ruos * Institute

of Social Technology, Suranaree University of Technology, Nakhon Ratchasima, 30000, Thailand Sereyrath Em, Phanommas Bamrungsin & Buratin Khampirat Authors * Daro Ruos View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sereyrath Em View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Phanommas

Bamrungsin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Buratin Khampirat View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS D.R., S.E., P.B., and B.K. wrote the main manuscript text, and D.R. and B.K. prepared Figs. 1 and 2. All authors reviewed the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Correspondence to Buratin Khampirat. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICAL STATEMENTS The study received ethical approval from the

ethics committee of the Royal University of Phnom Penh, Cambodia (136/2023 RUPPKS). The procedures used in this study adhere to the Helsinki Declaration and similar ethical standards.

INFORMED CONSENT We obtained consent from school administrators and classroom teachers, as these authorities are recognized in Cambodia as responsible for safeguarding the welfare of

students within educational institutions. Before taking part in this study, all participants received thorough information to ensure that they could make an informed decision. Participants

were informed about the study’s objectives, procedures, possible risks and advantages, confidentiality measures, and the notion that participation is completely voluntary and that withdrawal

at any time does not affect studying. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional

affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution

and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if

changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the

material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to

obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS

ARTICLE Ruos, D., Em, S., Bamrungsin, P. _et al._ The impact of instructional behaviors on learning motivation via subjective task value in high school students in Cambodia. _Sci Rep_ 15,

17344 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02147-z Download citation * Received: 13 January 2025 * Accepted: 12 May 2025 * Published: 19 May 2025 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02147-z SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * Learning motivation * Subjective task value * Intrinsic

motivation * Extrinsic motivation * Instructional behaviors * Structural equation modeling

![[withdrawn] co6 4nd, p g rix (farms) limited: environmental permit application advertisement](https://www.gov.uk/assets/static/govuk-opengraph-image-03837e1cec82f217cf32514635a13c879b8c400ae3b1c207c5744411658c7635.png)