- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict has significantly impacted mental health across neighbouring regions, with pregnant women being particularly vulnerable. This group faces

heightened risks of anxiety and depression due to the combined stresses of pregnancy and sociopolitical instability. Our study aimed to evaluate resilience as a protective factor against

anxiety and depression in Polish pregnant women during this crisis. From June 2, 2022, to April 11, 2023, we recruited participants and assessed their mental health using validated tools:

the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Labour Anxiety Questionnaire (LAQ), and self-developed War Anxiety and Global Situation Anxiety

Questionnaires (WAQ; GSAQ). Resilience was measured using the Resilience Measure Questionnaire (KOP26). Statistical methods included Spearman’s coefficient, Chi-Squared analysis, and the

Kruskal–Wallis test. The findings revealed a statistically significant negative correlation between resilience levels and depression symptoms as well as global situation anxiety,

underscoring resilience’s protective role. This property has not been confirmed in the context of war and labour anxiety. Current models showed limitations in accurately predicting mental

health outcomes, suggesting the need for more nuanced approaches. However, these results still emphasize resilience as crucial for perinatal psychological well-being, particularly during

global crises. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS ANXIETY AMONG PREGNANT WOMEN DURING THE FIRST WAVE OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC IN POLAND Article Open access 19 May 2022 THE RISK AND

PROTECTIVE FACTORS OF HEIGHTENED PRENATAL ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION DURING THE COVID-19 LOCKDOWN Article Open access 12 October 2021 VALIDATION OF PERINATAL POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER

QUESTIONNAIRE FOR SPANISH WOMEN DURING THE POSTPARTUM PERIOD Article Open access 10 March 2021 INTRODUCTION Motherhood is a period marked by profound hormonal, psychological, and social

changes that can increase susceptibility to mental health challenges1. According to a statistical report made by the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation2, approximately 5% of adults

worldwide suffer from depression, and 4% experience anxiety disorders. However, these rates are substantially higher among women in the perinatal period, with around 10% of pregnant women

and 13% of postpartum women affected by mental health disorders, with figures reaching 15.6% and 19.8%, respectively, in low- and middle-income countries3. Anxiety appears particularly

prevalent in this group, affecting up to 20.7% of perinatal women3, while depression impacts approximately 11.9%4, although significant differences emerge between high and low-income

countries5. These elevated rates underscore the unique vulnerabilities of perinatal women and the need for targeted research on mental health in this population, especially considering the

distinct stressors associated with pregnancy and childbirth. Perinatal mental health problems are associated with adverse consequences for future maternal and child health6, such as

neuroendocrine changes in the maternal brain7, altered neurodevelopment of the foetus and child8 pre-term birth or low birth weight9. Children born to mothers with perinatal anxiety and

depression often report development of insecure attachment, poor cognitive, motor and language development, behavioural disorders, and poor academic performance10. Furthermore, affected

mothers may face difficulties in recognizing the need for medical support and navigating healthcare services, leading to more frequent use of emergency medical care compared to those without

perinatal mental health issues11. Additionally, they are more likely to withdraw from their social networks and experience challenges in establishing a secure and responsive bond with their

neonates12. A major factor potentially affecting the perinatal health of Polish women is the event of February 24, 2022, when the Russian—Ukrainian war (RUW) began (Monk et al., 2019,13).

Even though Poland is not directly affected by the war, researchers suggest that the risk of psychological consequences is linked to, among other things, exposure to violence and suffering

from accounts of war and images circulating on social media14. It has been documented that many individuals in Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States also have experienced a

sense of threat, anger, and anxiety in response to Russia’s aggression, alongside a heightened sense of empathy for Ukrainian citizens15. A study from the Czech Republic shows that 34% of

young adults experienced moderate and 40.7% severe levels of anxiety and depression after the outbreak of the RUW16. In comparison, research on Polish citizens revealed that anxiety symptoms

measured using the GAD-7 questionnaire, were observed in 83.3% of respondents during the first month of the war and in 65.6% during the second month. While depression symptoms, measured by

the BDI-II, were reported by 52.8% of respondents in the first month and 64.7% in the second month of the war in Ukraine17. It is suggested that in Poland— a country with numerous

connections (historic, economic etc.) to Russia and Ukraine—people additionally have developed fears concerning their future involvement in the war and have been convinced that ‘sooner or

later we will be next’18. This heightened sense of threat may be particularly intense for pregnant women, who often experience elevated levels of anxiety related to their unborn child’s

safety under normal circumstances19,20 The additional stressors brought about by the war, such as fears of separation from loved ones, concerns about the well-being of their child in a

potentially unstable future, could exacerbate these anxieties21. An aspect that may worsen psychological well-being can be the fact that the war in Ukraine resulted in the largest refugee

crisis in Europe since World War II. Poland was the main country to initially receive refugees22. During the first ten weeks of the conflict, 2,377,000 refugees crossed Poland’s borders23.

From the outbreak of the war until the end of 2022, the Polish health care system admitted 350,096 patients from Ukraine, 4,306 Ukrainian children were born in Polish hospitals contracted

with the National Health Fund24. Despite fake news appearing on social media, according to the reports of the Polish Ombudsman for Patients’ Rights published at the beginning of 2023, there

was no increase in the number of complaints from Polish patients about the limited availability of health services due to assistance for Ukrainian citizens25. Further consequences had a more

severe impact on the Polish economy. The results of the Polish Economic Institute26 analysis of entrepreneurs’ assessments indicate that the war affected 60% of entrepreneurs to a moderate

or severe extent. Companies in the catering and accommodation sectors that have not yet dealt with the negative effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, because of the war, had to face a decline in

demand and high energy costs caused by constantly rising inflation. It reached its highest level, i.e. 18%, in February 202327. 45% of respondents indicated higher operating costs,

increasing prices of products or services offered26. Unfortunately, a very limited number of studies dealt with the impact of the RUW on citizens of neighbouring countries16 such as

Poland28. Even more so on a group of Polish women17, and none on a group of Polish women in the perinatal period, which are extremely susceptible to the negative impact of stressors. Despite

established risk factors, certain psychosocial factors have the potential to shield women during the perinatal period from the adverse effects of distress. One of them is resilience,

defined as the result of a complex and dynamic process of adaptation to adversity, resulting in the maintenance of mental well-being29. Resilience is considered as both a mediator and

moderator between stress exposure and symptoms of anxiety and depression30,31. Resilience has been noted to have a positive correlation with extraversion and conscientiousness and a negative

correlation with neuroticism32. What is more, it is linked with qualities like social support, self-efficacy, self-belief, adaptive emotion regulation strategies and optimism29,33.

Referring directly to the specificity of the target group, which is pregnant women, we should also pay attention to the fact that ability to prevent or adapt to stressful life events is

intrinsically linked to pregnant women’s support systems, including a good health system and a good financial environment34. Therefore, the aim of the presented study was to determine

whether there are connections between mental resilience and the negative effects of the RUW as well as symptoms of depression and anxiety in women in the perinatal period. As part of the

study, we set the following research hypotheses: * 1. Psychological resilience functions as a protective factor against perinatal depression, labour anxiety, global situational and

war-related anxiety, with higher resilience levels associated with significantly lower severity of these mental health challenges in pregnant women. * 2. Resilience serves as a predictor of

depression and anxiety in pregnant women. MATERIALS AND METHODS STUDY POPULATION AND METHODS Women during pregnancy were recruited with the use of the snowball method, through social media,

with a fanpage dedicated to the study and by sharing leaflets with information about the study in gynaecology and obstetrics clinics in the Lodz voivodeship. The recruitment efforts lasted

from June 2, 2022, to April 11, 2023. Participants voluntarily took part in the study. Eligibility requirements consisted of being pregnant at the time of entering the study. Further,

participants had to live in Poland, be fluent enough in the Polish language to be able to complete the questionnaires and lastly, they had to be at least 18 years old. The questionnaires

were administered through Google Forms and the estimated average time to finish the questionnaire battery was ten minutes. Duplication was avoided by conducting verifications based on the

e-mail addresses and dates of birth provided by participants when completing the survey. The above data was recorded to ensure that duplicate responses from the same individuals were

avoided. This method also facilitated follow-up with participants, allowing the research team to contact them for completing subsequent questionnaires and ensuring the integrity of the data

collected. Informed consent to participate in the study was given electronically by all participants. Participation in the study was completely voluntary, and information was provided about

the study’s objectives and protocols established to maintain confidentiality of the data we collected. Consent to participate was indicated through the completion of the online survey and

submission of the form and participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point. Participants who didn’t fully complete the questionnaires or meet the

eligibility requirements were excluded from the study. If any participants reached a score above the cut-off point for depression symptoms, an e-email was sent to them, with information that

the symptoms they may be experiencing, could be a sign of a depression episode and require an assessment by a mental health specialist, a psychiatrist or psychologist. The need to make the

gynaecologist or midwife aware of the questionnaire results was emphasised. Additionally, a list was provided of places available to seek support in the diagnosis and treatment of perinatal

mental disorders. Ethical approval by the Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Lodz to carry out this study was obtained on February 9th, 2023, under the reference number

RNN/39/21/KE. This cross-sectional study was the second part of a longitudinal examination aiming to research the relationship between resilience and mental health in perinatal women.

MEASURES RESILIENCE Resilience was measured using the Polish questionnaire—Kwestionariusz Oceny Prężności (KOP-26), whose authors are Gąsior, Chodkiewicz and Cechowski35. The instrument is

used to test adults, and it defines resilience as the combination of personal, social, and family competence. The questionnaire consists of 26 items rated on a five-point scale. The

instrument was validated on a study group of 721 people and the internal validity for the whole instrument was checked with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient to be 0.90. According to the norms

from the normative study for the Kwestionariusz Oceny Prężności (KOP-26) questionnaire, scores at or below 97 mean low resilience, scores between 98 and 109 mean medium resilience and scores

at or higher than 110 mean high resilience. Comparisons with other constructs measuring resilience were also made, namely Resilience Measure Scale (SPP-25) (r = 0.62); Ego Resilience Scale

(ER) (r = 0.59), feeling of coherence with Life Orientation Questionnaire (SOC-29) (r = 0.60) and lastly, social support with the Social Support Scale (F-SozU) (r = 0.57). Cronbach’s alpha

for the present sample was 0.926 for the family relations subscale, 0.914 for the personal competence subscale and 0.873 for the social competence subscale. MATERNAL DEPRESSION SYMPTOMS

Maternal depression symptoms were measured with two tools, the Polish adaptation of The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) by E. Łojek, E. Stańczak36 and the Polish adaptation of the

Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) by Dr. Kossakowska37. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) score range is 0–63 and the tool’s Polish adaptation was normalised by Łojek and

Stańczak36 on 574 people. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the instrument was shown to be 0.91 and 0.93 for people diagnosed with depression,the test–retest method also showed no

statistically significant differences. According to the norms, scores up to 15 are considered normal and scores above 15 could be indicative of clinically significant depression symptoms.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the present sample was found to be 0.918. The Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) consists of 10 items describing different aspects of a woman’s

well-being which are rated on a four-point scale. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the instrument was shown to be 0.91. The author further used the test–retest method and found no

statistically significant differences between measurements. The KMO test was found to have a value of 0.86. Factor analysis also showed satisfactory results and the general score of the

scale was compared with Beck’s depression scale (r = 0.836; p < 0.01). A cutoff threshold of 13 for the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale score indicating clinically significant

depression symptoms was used. Cronbach’s alpha for the present sample was 0.901. Both the Beck Depression Inventory-II and the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale are used in this study

because this allows for more reliable detection of depression symptoms than either tool would manage on its own, considering that the Beck Depression Inventory-II wasn’t developed

specifically for women in the perinatal period, while the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale is a tool commonly used in perinatal care and has been validated for screening depression

during pregnancy as well as in the postnatal period.38 This study was part of a broader project in which the participants were followed up on after giving birth, in their postnatal period.

We believe the use of two tools measuring depression strengthens our results, even though the polish version of the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale was not validated for pregnant women

specifically. MATERNAL SITUATIONAL ANXIETY SYMPTOMS To measure maternal situational anxiety symptoms, we used three instruments. The first one was the self-report Labour Anxiety

Questionnaire (LAQ; original Kwestionariusz Lęku Porodowego—KLP II), which consists of 9 items rated on a four-point scale, including attitudes towards labour and fear of labour39.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was shown to be 0.69 during the instrument’s normalisation study. A score of 13 or less in the questionnaire shows a low level of labour anxiety, 14–15 points

show a slightly elevated level of labour anxiety while 16–17 points show a high level of labour anxiety and a score of 18 points or more shows a very high level of labour anxiety. The Global

Situation Anxiety and War Anxiety Questionnaires (GSAQ and WAQ) were first created as a single questionnaire, however, during the development process, it was decided that dividing the

questionnaire into two separate tools would enhance their validity and specificity. Items from the original version were reviewed and removed where necessary, in order to achieve the best

internal consistency. We believe the development process for the two questionnaires made them suited to the specific context of this study, considering that our goal was to evaluate

resilience as a protective factor against anxiety and depression among Polish pregnant women during the Ukraine war crisis. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient results also prove the high

internal consistency of the tools. GLOBAL SITUATION ANXIETY An original Global Situation Anxiety Questionnaire developed by an interdisciplinary team of psychiatrists and psychologists,

assesses anxiety due to societal issues through four questions concerning personal safety amid economic woes, inflation effects, migration crises, and armed conflict threats. Individuals

rate their concern on a 10-point scale, where 1 is minimal concern and 10 is maximum. This tool, with a reliability coefficient of 0.84, effectively captures the psychological impact of such

concerns. WAR ANXIETY War anxiety was measured using the War Anxiety Questionnaire, which is an original tool developed for this research by an interdisciplinary team of psychiatrists and

psychologists. The Questionnaire consists of 11 items assessing anxiety related to armed conflicts—it covers the geopolitical impact on personal life, engagement with conflict news, family

discussions, contingency planning, and the emotional effect of media war reports. The items use a 6-point Likert scale. This tool aims to gauge war’s psychological impact, boasting a

reliability coefficient of 0.81. DATA ANALYSIS IBM SPSS 29 was used to analyse the collected data. Chi-square analysis was performed on resilience levels classified as low, medium, and high

for depression classified according to its questionnaire-specific norms and to examine frequency differences between demographic variables. Due to an insufficient number of cells for this

analysis, Fisher’s test was performed for childbirth anxiety in relation to resilience. Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests were performed using resilience as the independent variable. The

intention was to further assess the normality of distribution and homogeneity of variance due to unsatisfactory rates of kurtosis, which was often close to -1, but we were unable to confirm

either. In light of this, analysis was performed using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test, and Dunnett’s T3 was used for post hoc analysis. Associations between main continuous variables

were measured using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Simple linear regression models were created using resilience as. a predictor variable for each model and testing for labour

anxiety, war anxiety, global situation anxiety, and depression. RESULTS SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS A total of 156 Polish pregnant women met the inclusion criteria and provided completed

questionnaires. A quarter of the women from our study reported having previously undergone psychiatric treatment. However, further questions showed that only four were currently in

treatment, with two on pharmacotherapy and two only using psychotherapeutic help. Among the 32 women who reported experiencing complications during the current pregnancy, gestational

diabetes and a risk of a genetic disorder of the foetus were most commonly reported. Descriptive data statistics can be seen in Table 1 while full sample characteristics are shown in Table

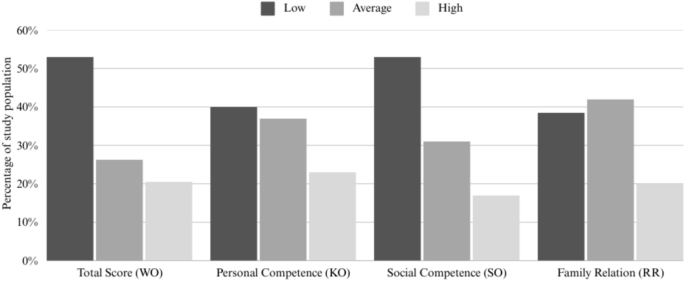

2. The resilience levels in our study population can be seen in Fig. 1. An in-depth look at the mechanisms of psychopathology is presented in the article of Barszcz et al.40 SUBGROUP

ANALYSIS Chi-Squared analysis revealed no statistically significant differences with regards to the analysed socio-demographic variables between subgroups, but we found statistically

significant (p < 0.001) differences between groups with different resilience levels and clinically significant depression symptoms. Socio-demographic characteristics of our study

population in relation to the resilience levels are presented in Table 3 while full results of a comparison of depression and anxiety with relation to resilience levels can be seen in Table

4. ASSOCIATIONS BETWEEN RESILIENCE AND DEPRESSION OR ANXIETY Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed statistically significant associations between resilience and depression with a moderate

effect size (r = -0.485; p < 0.001) as well as between resilience and global situation anxiety with a weak effect size (r = -0.232; p < 0.05). Full results of this analysis are shown

in Table 5. MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS OF RESILIENCE Analysis with the Kruskal–Wallis test using resilience as the independent variable found that the distributions of the depression (EPDS—F =

29.452; df = 2; p < 0.001; BDI-II—F = 34.966; df = 2; p < 0.001) and global situation anxiety (F = 8.921; df = 2; p = 0.012) variables were different with statistical significance in

at least one of the compared groups. Results of the Kruskal–Wallis analysis can be seen in Fig. 2, Fig. 3 and Fig. 4. Post Hoc analysis results using Tamhane’s T2, Dunnett’s T3 and

Games-Howell tests can be seen in Table 6. No statistically significant results were found for labour and war anxiety. POSSIBLE PREDICTORS ANALYSIS Simple linear regression analysis showed

that our resilience models only had statistical significance with depression (p < 0.001) and global situation anxiety (p < 0.010). However, none of the tested models were proven to be

well-fitted to the empirical data and useful for prognosis, with the R-squared values being 0.042 for global situation anxiety and 0.208 for depression. DISCUSSION Our study identified

statistically significant relationships between resilience and various psychological outcomes in the perinatal period. We found a moderate negative association between resilience and

depressive symptoms, as well as a weaker but statistically significant negative correlation between resilience and global situation anxiety. These findings may, after further analysis in

future research, elucidate how global crises affect mental health, particularly among at-risk populations, such as women in the perinatal period. Conversely, no significant associations were

observed between resilience and labour anxiety or war anxiety. In the following sections, we will explore potential explanations for the absence of these correlations and examine the

broader implications of our findings. However, these results highlight the protective potential of resilience in certain contexts while also underscoring its limitations in addressing more

specific or acute forms of anxiety, as reports other research41. In our study, we obtained a statistically significant negative correlation between resilience and depression with a

correlation strength like the results obtained for the Italian population42 and similar to the results of the Spanish study43. Almost all our participants who were found to have clinically

significant depression symptoms, also had a low level of resilience. This result may further emphasize the protective nature of resilience against the risk of depression in pregnant women.

Similar relationships were observed during the recent, well-researched global crisis that affected Poland and the world, the Covid-19 pandemic. A low level of resilience during pregnancy,

recorded during the Covid-19 pandemic, may have been a significant predictor of the severity of depression symptoms44. Similar conclusions were also reached in research not concerning global

crises, showing that being more resilient may in some form help better protect an individual against negative mental health outcomes, in particular depression and anxiety, PTSD, stress, and

psychological distress45. This consistency with international data reinforces the notion that resilience serves as a protective factor, particularly against depression. However, while our

findings demonstrate its relevance, the moderate effect size suggests that resilience alone cannot fully account for the variance in depression symptoms, likely requiring additional

biological, psychological and environmental factors46,47. Our results also revealed a statistically significant negative correlation between resilience and global situation anxiety. Among

the women showing signs of significant global situation anxiety, only one had high resilience, and most had a low level of resilience. However, the protective effect was limited, as

evidenced by the relatively small effect size. Nonetheless, our results may correspond with the case of the 2008 financial crisis, researchers such as Botou et al.48, concentrating on the

Greek population, pointed to the protective nature of psychological resilience in the context of coping with the consequences of the economic crisis. Furthermore, our linear regression

analysis showed that resilience could affect depressiveness or global situation anxiety in a statistically significant way. However, since our model did not fit well enough with the

empirical data, this conclusion should be considered with a very high degree of caution. Similar results were also noted in studies involving adult Israeli citizens particularly exposed to

terrorist attacks in 2015. In that context, psychological resilience also wasn’t the best predictor of depression following a terrorist event. An analysis of the influence of all predictors,

mutually controlled, showed that the most consistent predictor of future depression was a sense of coherence before the adversity occurred41. A deeper exploration of resilience subscales

revealed that the personal competence component of resilience demonstrates a stronger negative association with global situation anxiety than other resilience subscales, underscoring its

pivotal role in mitigating anxiety during the perinatal period. This suggests that individuals with greater self-efficacy and goal-setting abilities may better cope with diffused,

non-specific stressors such as economic instability or geopolitical unrest. On the other hand, social competence, as a subscale of resilience, showed no significant relationship with global

situation anxiety, indicating that external social support alone may be insufficient in mitigating global situation anxiety, which is also indicated by other studies49 It is important to

note that about 40% of our respondents were characterised by a low level of personal competence. These women may not have believed in their own abilities and skills and may have had

difficulty setting a clear goal and planning a path to achieve it. Moreover, some of them may have struggled with recognizing their lives as valuable35. We think that this area may be

particularly important in the context of introducing psychological interventions and it is worth taking up and expanding the above topics in subsequent research, to further develop these

issues in the context of specific circumstances. Notably, resilience did not exhibit a significant relationship with labour anxiety or war anxiety in our study. This result diverges from

previous research, such as studies conducted on Chinese and Polish populations during the COVID-19 pandemic, which found significant negative correlations between resilience and labour

anxiety with a moderate and strong effect size, respectively50,51. One of the many potential explanations for this discrepancy could be the fact of overlapping crises over several years.

Richter et al.52 were among the first to note the complex impact of intersecting global crises on mental health, while highlighting specific trends at both the population and individual

level. The results showed that it was, among other things, the economic threat, in the form of the danger of an increase in the cost of living, and the danger of the Covid-19 pandemic that

had the greatest impact on the mental state of the German general population. In the context of the perinatal period during the COVID-19 pandemic, access to healthcare services became

significantly more challenging. Many countries implemented changes to prenatal care protocols, often limiting in-person visits to urgent cases or postponing non-essential appointments. In

some regions, pregnant women were advised to visit hospitals only for childbirth. The reduced availability of medical consultations, combined with unsettling media reports, contributed to

heightened anxiety and uncertainty among expectant mothers53,54. The migration crisis in Poland, which came a few months later with the outbreak of the Ukrainian-Russian war and the

resulting additional strain on hospital resources in the country, could also prove to be a potential stressor for women expecting a child and translate into chronically persistent concerns

about childbirth55,56. Considering resilience as a meta-resource (Kaczmarek et al., 2011) during the war and economic crisis immediately following the pandemic, resilience resources may not

have had sufficient time to rebuild. The stress resulting from the combination of these two events may have contributed to the depletion of resources available to women. In such an

environment, resilience alone may not have been sufficient to alleviate the profound psychological stress experienced by mothers. Similar conclusions can be drawn from studies that suggest

that in extreme and traumatic situations, such as war or major humanitarian crises, resilience may have limited effectiveness in preventing psychological damage57. A weakening, or

disappearance, of the protective nature of resilience was observed for, among others, Yazidi women who were exposed to attacks by the Islamic State terrorist group. Studies have shown that

for women experiencing a traumatising, prolonged (more than 3 years) stressor, no association between resilience and the occurrence of PTSD or cPTSD was observed58, or only reduced levels of

resilience were observed59. Our findings indicate that resilience plays a role in mitigating the effects of broad sociopolitical stressors, such as global situation anxiety, but appears

less effective in buffering against more acute anxieties, including labour and war-related concerns. The observed lack of correlation may stem from the unique psychological demands of these

stressors, which require different coping mechanisms beyond resilience alone. For example, labour anxiety is often linked to factors such as previous birth experiences, pain perception, and

medical care expectations, while war anxiety may be influenced by an individual’s direct or indirect exposure to conflict-related media, personal security concerns, or proximity to affected

regions. These factors could override the protective function of resilience, suggesting the need for more targeted psychological interventions.Another of the potential explanations why this

correlation could have been muted is due to our failure to consider the potential factor differentiating the study group, namely the impact of the neurobiological burden resulting from

complications after Covid-19. These complications included, among others: executive function deficits60, behavioral inhibition, or attention disorders61. As research indicates, both

executive functions62 and behavioral inhibition63 play roles in the process of adaptation to existing environmental conditions. Failure to take into account the above variable could have

influenced the results achieved. From an economic and social perspective, financial status and access to private healthcare could be potentially crucial factors. Resilience, defined as the

ability to adapt to stress, is linked to support systems, including good healthcare and financial stability34. Research shows these factors are interdependent, with one compensating for the

weakness of the other64. According to the international research review, private healthcare service costs have been noted to be rising. Finding a major disproportion between study

participants could translate into the appearance of a positive or negative association, while a uniform distribution between use of the public and private healthcare sectors could lead to

the observed lack of an association between resilience and labour anxiety. Overall, our findings suggest that while resilience, particularly personal competence, offers some protection

against broad and diffused stressors like global situation anxiety, it appears less effective in the face of specific and acute stressors, such as labour or war-related anxieties. This

distinction underscores the need for tailored interventions that consider the nuanced ways in which resilience operates under varying stress conditions. Future research should further

investigate these dynamics and explore interventions aimed at strengthening personal competence to enhance resilience in at-risk populations during the perinatal period. CONCLUSION Based on

our results it appears that resilience, in relation to specific conditions such as man-made disasters, does not constitute a sufficient factor for predicting the risk of depression or

anxiety. We suggest that, when dealing with difficult emotional responses in conditions of prolonged armed conflict, attention should be paid to other potential protective factors or risk

factors. We find resilience by itself to be insufficient as a measure used to screen women in the perinatal period to see whether they may be at risk of any mental health issues related to

pregnancy and could require closer monitoring or any psychological interventions. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS Although every effort was made to recruit a diverse and representative sample of

participants, the limited representativeness of our sample, consisting of 156 women, most of whom were highly educated and residing in large urban areas, and the limited size of our sample

may affect the generalizability of our results. This sample bias was likely influenced by our recruitment method, which mainly relied on online surveys. The main participation criterion was

a self-reported declaration of current pregnancy at the time of enrolment. However, we were unable to independently confirm the accuracy of these self-reported pregnancy statuses. Our

original tools, the War Anxiety Questionnaire and Global Situation Questionnaire developed specifically for the needs of this study by experts haven’t gone through the full validation

process. It’s also important to note, that our study was cross-sectional, which holds its own drawbacks. Despite these limitations, our study contributes essential data on the relationship

between resilience and the adverse outcomes of the RUW on the psychological well-being of Polish women in the perinatal period. We anticipate that these findings will enhance understanding

of mental health concerns in the perinatal population, particularly in relation to potential future crises of an economic or wartime nature. DATA AVAILABILITY The dataset used for the study

is available per request. Please contact [email protected]. REFERENCES * Akseer, N. et al. Coverage and inequalities in maternal and child health interventions in Afghanistan. _BMC

Public Health_ 16(Suppl 2), 797. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3406-1 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Barszcz, E., Plewka, M., Gajewska, A., Margulska, A.

& Gawlik-Kotelnicka, O. Perinatal depression, labor anxiety and mental well-being of Polish women during the perinatal period in a war and economic crisis. _Psy. Interpers. Biol.

Processes_ https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2024.2447219 (2025). Article Google Scholar * Bhamani, S. S. et al. Resilience and prenatal mental health in Pakistan: a qualitative inquiry.

_BMC Preg. Childbirth_ 22(1), 839. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05176-y (2022). Article Google Scholar * Botou, A., Mylonakou-Keke, I., Kalouri, O. & Tsergas, N. Primary school

teachers’ resilience during the economic crisis in Greece. _Psychology_ 8, 131–159. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2017.81009 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Burger, M., Hoosain, M.,

Einspieler, C., Unger, M. & Niehaus, D. Maternal perinatal mental health and infant and toddler neurodevelopment - Evidence from low and middle-income countries. A systematic review. _J.

Affect. Disord._ 268, 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.023 (2020). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Dębkowska, K., Kłosiewicz-Górecka, U., Szymańska, A., Wejt-Knyżewska, A.,

Zybertowicz, K. (2023), Wpływ wojny w Ukrainie na działalność polskich firm, Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny, Warszawa. * EEC. (2024). Czas transformacji. Wnioski i rekomendacje. (Accessed

16.12.2024) at https://pliki.rynekzdrowia.pl/i/21/14/48/211448.pdf * Fatyga, E., Dzięgielewska-Gęsiak, S. & Muc-Wierzgoń, M. Organization of medical assistance in poland for ukrainian

citizens during the Russia-Ukraine War. _Front. Public Health_ 10, 904588 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fawcett, E. J., Fairbrother, N., Cox, M. L., White, I. R.

& Fawcett, J. M. The prevalence of anxiety disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period: A multivariate Bayesian meta-analysis. _J Clin Psych._ 80, 12527.

https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.18r12527 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Gąsior, K., Chodkiewicz, J., Cechowski, W. (2016). Polskie Forum Psychologiczne, 21(1), 76–92.

https://doi.org/10.14656/PFP20160106 * Grossman, E. et al. Preliminary evidence linking complex-PTSD to insomnia in a sample of yazidi genocide survivors. _Psy. Res._

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.044 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Grzankowska, I., Wójtowicz-Szefler, M. & Deja, M. Selected determinants of anxiety and depression

symptoms in adolescents aged 11–15 in relation to the pandemic COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine. _Front. Public Health_ 12, 1480416. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1480416 (2025). Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * GUS, WHO. (2022). Health of refugees from Ukraine in Poland 2022. _Household survey and behavioural insights research._ * GUS. Wykres CPI.

https://stat.gov.pl/wykres/1.html (Accessed 16.12.2024) * Hadad, R. et al. Cognitive dysfunction following COVID-19 infection. _J. Neurovirol._ 28(3), 430–437.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-022-01079-y (2022). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hajure, M. et al. Resilience and mental health among perinatal women: a systematic

review. _Front. Psych._ 15, 1373083. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1373083 (2024). Article Google Scholar * Hodel, A. S. Rapid infant prefrontal cortex development and sensitivity to

early environmental experience. _Developmental review: DR_ 48, 113–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.02.003 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Institute of Health Metrics and

Evaluation. Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (Accessed 16.12.2024). * Ionio, C. et al. COVID-19: what about pregnant women during first lockdown

in Italy?. _J. Reprod. Infant Psychol._ 40(6), 577–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2021.1928614 (2022). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Jankowski, M. et al. One year on: Poland’s

public health initiatives and national response to millions of refugees from Ukraine. _Med. Sci. Monit._ 29, e940223 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kasierska, M.

et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in polish population in the context of the war in ukraine: analysis of risk factors and practical implications. _Sustainability._ 15(19), 14230.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914230 (2023). Article Google Scholar * Kimhi, S., Eshel, Y. & Bonanno, G. A. Resilience protective and risk factors as prospective predictors of

depression and anxiety symptoms following intensive terror attacks in Israel. _Pers. Ind. Dif._ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109864 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Krupelnytska, L.

et al. War in Ukraine vs. Motherhood: Mental health self-perceptions of relocated pregnant women and new mothers. _BMC Pregnancy Childbirth_ 25(1), 253.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-025-07346-0 (2025). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Klabbers, G. A., van Bakel, H. J., van den Heuvel, M. & Vingerhoets, A. J. Severe

fear of childbirth: its features, assesment, prevalence, determinants Consequences and Possible Treatments. _Psychol. Top._ 25, 107–127 (2016). Google Scholar * Konaszewski, K.,

Niesiobędzka, M. & Surzykiewicz, J. Resilience and mental health among juveniles: Role of strategies for coping with stress. _Health Qual. Life Outcomes_ 19, 58.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01701-3 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kornfield, S. L. et al. Risk And resilience factors influencing postpartum depression

and mother-infant bonding during COVID-19. _Health affairs (Project Hope)_ 40(10), 1566–1574. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00803 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Kossakowska, K. (2013). Edynburska skala depresji poporodowej - właściwości psychometryczne i charakterystyka. _Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Psychologica_.

https://doi.org/10.18778/1427-969X.17.03 * Kossowska, M., Szwed, P., Szumowska, E., Perek-Białas, J. & Czernatowicz-Kukuczka, A. The role of fear, closeness, and norms in shaping help

towards war refugees. _Sci. Rep._ 13(1), 1465. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28249-0 (2023). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kotera, Y., Green, P. &

Sheffield, D. Positive psychology for mental wellbeing of UK therapeutic students: Relationships with engagement, motivation, resilience and self-compassion. _Int. J. Ment. Health Addict._

20, 1611–1626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00466-y (2022). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Lagadec, N. et al. Factors influencing the quality of life of pregnant women: a

systematic review. _BMC Preg. Childbirth_ 18(1), 455. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2087-4 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Levis, B., Negeri, Z., Sun, Y., Benedetti, A. & Thombs,

B. D. Accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for screening to detect major depression among pregnant and postpartum women: systematic review and meta-analysis of

individual participant data. _BMJ (Clinical research ed.)_ 371, m4022. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4022 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * LubiánLópez, D. M. et al.

Resilience and psychological distress in pregnant women during quarantine due to the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain: a multicentre cross-sectional online survey. _J. Psychos. Obstetr. Gynecol._

42(2), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2021.1896491 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Łojek, E., Stańczak, J. (2019). inwentarz depresji Becka : BDI - II. Pracownia Testów

Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Psychologicznego. * Ma, R. et al. Resilience mediates the effect of self-efficacy on ssymptoms of prenatal anxiety among pregnant women: a nationwide

smartphone cross-sedbgctional study in China. _BMC Pregnancy Childbirth_ 21, 430. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03911-5 (2021). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Makinde, O. A. et al. Resilience in maternal, newborn, and child health in low- and middle-income countries: findings from a scoping review. _Reprod. Health_ 22(1), 4.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-025-01947-w (2025). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Masuyama, A., Kubo, T., Shinkawa, H. & Sugawara, D. The roles of trait and process

resilience in relation of BIS/BAS and depressive symptoms among adolescents. _PeerJ_ 10, e13687. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13687 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Méndez, R. et al. Short-term neuropsychiatric outcomes and quality of life in COVID-19 survivors. _J. Intern. Med._ 290(3), 621–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13262 (2021). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mana, A. et al. Individual, social and national coping resources and their relationships with mental health and anxiety: A comparative study in

Israel, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands during the Coronavirus pandemic. _Glob. Health Promot._ 28(2), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975921992957 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * MizrakSahin, B. & Kabakci, E. N. The experiences of pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey: A qualitative study. _Women and Birth : J Austr.

College o Midwives_ 34(2), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2020.09.022 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Moshagen, M., Hilbig, B. E. (2022). Citizens’ Psychological Reactions

following the Russian invasion of the Ukraine: A cross-national study. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/teh8y * Nowicka, M., Jarczewska-Gerc, E. & Marszal-Wisniewska, M. Response of

Polish psychiatric patients to the russian invasion of Ukraine in february 2022-predictive role of risk perception and temperamental traits. _Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health_ 20(1), 325.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010325 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Oshio, A., Taku, K., Hirano, M. & Saeed, G. Resilience and Big Five personality traits:

A meta-analysis. _Personality Individ. Differ._ 127, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.048 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Operto, F. F. et al. Neuropsychological profile,

emotional/behavioral problems, and parental stress in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. _Brain Sci._ 11(5), 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050584 (2021). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Pluym, I. D. et al. Emergency department use among postpartum women with mental health disorders. _American journal of obstetrics & gynecology MFM_

3(1), 100269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100269 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Putyński, L. & Paciorek, M. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. _Folia Psychologica_ 12, 129–133

(2008). Google Scholar * Raz, S. Behavioral and neural correlates of cognitive-affective function during late pregnancy: an Event-Related Potentials study. _Behav. Brain Res._ 267, 17–25.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2014.03.021 (2014). Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar * Riad, A. et al. Mental health burden of the Russian-Ukrainian War 2022 (RUW-22): Anxiety and

depression levels among young adults in Central Europe. _Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health_ 19(14), 8418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148418 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Richter, E. P. et al. Compounded effects of multiple global crises on mental health: A longitudinal study of East German adults. _J. Clin. Med._ 13(16), 4754.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164754 (2024). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rodríguez-Muñoz, M. F. et al. The impact of the war in Ukraine on the perinatal period:

Perinatal mental health for refugee women (pmh-rw) protocol. _Front. Psychol._ 14, 1152478. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1152478 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Rogers, A. et al. Association between maternal perinatal depression and anxiety and child and adolescent development: A meta-analysis. _JAMA Pediatr._ 174(11), 1082–1092.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2910 (2020). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Roos, A. et al. Selective attention to fearful faces during pregnancy. _Prog.

Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry_ 37(1), 76–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.11.012 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Schäfer, S. K., Kunzler, A. M., Kalisch, R.,

Tüscher, O. & Lieb, K. Trajectories of resilience and mental distress to global major disruptions. _Trends Cogn. Sci._ 26(12), 1171–1189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2022.09.017

(2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Schiff, M. et al. Do adolescents know when they need help in the aftermath of war?. _J. Trauma. Stress_ 23(5), 657–660.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20558 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Shorey, S. et al. Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression among healthy mothers: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. _J. Psychiatr. Res._ 104, 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.08.001 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Śliwerski, A., Kossakowska, K., Jarecka, K.,

Świtalska, J. & Bielawska-Batorowicz, E. The effect of maternal depression on infant attachment: A systematic review. _Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health_ 17(8), 2675.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082675 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Snyder, H. R., Miyake, A. & Hankin, B. L. Advancing understanding of executive function

impairments and psychopathology: Bridging the gap between clinical and cognitive approaches. _Front. Psychol._ 6, 328. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00328 (2015). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sójta, K. et al. Resilience and psychological well-being of Polish women in the perinatal period during the COVID-19 pandemic. _J. Clin. Med._ 12(19), 6279.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196279 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Stawicki, A. & Dziekanowska, M. Resilience in action: Poland’s response to the migration

crisis caused by the war in Ukraine. _Int. Migrat._ 63, e70012. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.70012 (2025). Article Google Scholar * Studniczek, A. & Kossakowska, K. Experiencing

Pregnancy during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Mediating Effect of Resiliency on Prenatal Depression Symptoms. _Behavioral sciences (Basel, Switzerland)_

12(10), 371. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100371 (2022). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Taha, P. H., Nguyen, T. P. & Slewa-Younan, S. Resilience and Hope Among Yazidi Women Released

From ISIS Enslavement. _J. Nerv. Ment. Dis._ 209(12), 918–924. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001400 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Van Haeken, S. et al. Perinatal

resilience for the First 1000 days of life concept analysis and Delphi survey. _Front. Psychol._ 11, 563432. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.563432 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Vindevogel, S. Resilience in the context of war: A critical analysis of contemporary conceptions and interventions to promote resilience among war-affected children and

their surroundings. _Peace Conflict J. Peace Psychol._ 23, 76–84 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Woody, C. A., Ferrari, A. J., Siskind, D. J., Whiteford, H. A. & Harris, M. G. A

systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. _J. Affect. Disord._ 219, 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003 (2017). Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Zhang, D. W. et al. Electroencephalogram theta/beta ratio and spectral power correlates of executive functions in children and adolescents with AD/HD. _J. Attent.

Disord._ 23, 721–732. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717718263 (2019). Article Google Scholar Download references FUNDING This research did not receive any specific grant from funding

agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Institute of Psychology, University of Lodz, al. Rodziny Scheiblerów 2, 90-128,

Lodz, Poland Zofia Błaszczyk & Andrzej Wyrzychowski * Department of Electrocardiology, Central Teaching Hospital, Medical University of Lodz, Pomorska 251, 91–213, Łódź, Poland

Maksymilian Plewka * Department of Clinical Psychology and Psychopathology, Institute of Psychology, University of Lodz, al. Rodziny Scheiblerów 2, 90-128, Lodz, Poland Katarzyna

Nowakowska-Domagała * Department of Affective and Psychotic Disorders, Medical University of Lodz, Czechoslowacka Street 8/10, 92-216, Lodz, Poland Dominik Strzelecki & Oliwia

Gawlik-Kotelnicka Authors * Zofia Błaszczyk View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Andrzej Wyrzychowski View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Maksymilian Plewka View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Katarzyna Nowakowska-Domagała View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Dominik Strzelecki View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Oliwia Gawlik-Kotelnicka View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS ZB—Writing – Original draft, Literature review AW – Formal

analysis, Data interpretation MP—Data collection and monitoring KN-D – Supervision, Work consultation DS– Supervision, Critical feedback O G-K—Study design, Writing – review and editing,

Manuscript approval. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Oliwia Gawlik-Kotelnicka. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with

respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article. ETHICAL APPROVAL The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics

Committee at the Medical University of Lodz (RNN/39/21/KE, 9 February 2023). ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International

License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the

source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived

from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line

to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS

ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Błaszczyk, Z., Wyrzychowski, A., Plewka, M. _et al._ Resilience of pregnant Polish women during the war between Ukraine and Russia. _Sci Rep_ 15, 16228 (2025).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01108-w Download citation * Received: 22 December 2024 * Accepted: 04 May 2025 * Published: 09 May 2025 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01108-w

SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to

clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * Resilience * Anxiety * Depression * Pregnancy * Ukraine war * Global crisis

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(319x0:321x2)/people_social_image-60e0c8af9eb14624a5b55f2c29dbe25b.png)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(959x599:961x601)/lisa-bonet-lenny-kravitz-1-87a7faf4fa484960abfedcc8085e0fe6.jpg)