- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Frailty, social isolation, and loneliness have individually been associated with adverse health outcomes. This study examines how frailty in combination with loneliness or social

isolation is associated with socioeconomic deprivation and with all-cause mortality and hospitalisation rate in a middle-aged and older population. Baseline data from 461,047 UK Biobank

participants (aged 37–73) were used to assess frailty (frailty phenotype), social isolation, and loneliness. Weibull models assessed the association between frailty in combination with

loneliness or social isolation and all-cause mortality adjusted for age/sex/smoking/alcohol/socioeconomic-status and number of long-term conditions. Negative binomial regression models

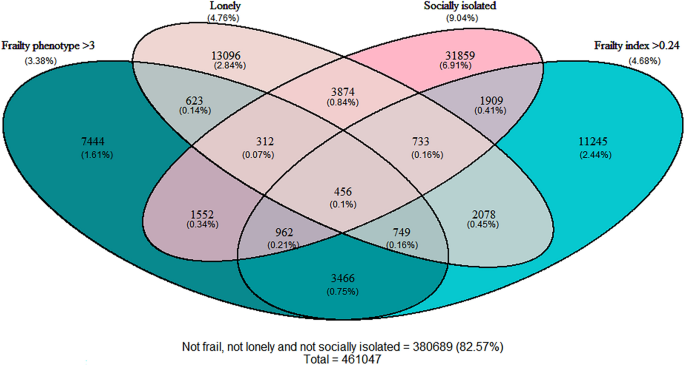

assessed hospitalisation rate. Frailty prevalence was 3.38%, loneliness 4.75% and social isolation 9.04%. Frailty was present across all ages and increased with age. Loneliness and social

isolation were more common in younger participants compared to older. Co-occurrence of frailty and loneliness or social isolation was most common in participants with high socioeconomic

deprivation. Frailty was associated with increased mortality and hospitalisation regardless of social isolation/loneliness. Hazard ratios for mortality were 2.47 (2.27–2.69) with social

isolation and 2.17 (2.05–2.29) without social isolation, 2.14 (1.92–2.38) with loneliness and 2.16 (2.05–2.27) without loneliness. Loneliness and social isolation were associated with

mortality and hospitalisation in robust participants, but this was attenuated in the context of frailty. Frailty and loneliness/social isolation affect individuals across a wide age spectrum

and disproportionately co-occur in areas of high deprivation. All were associated with adverse outcomes, but the association between loneliness and social isolation and adverse outcomes was

attenuated in the context of frailty. Future interventions should target people living with frailty or loneliness/social isolation, regardless of age. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS

A LONGITUDINAL ANALYSIS OF LONELINESS, SOCIAL ISOLATION AND FALLS AMONGST OLDER PEOPLE IN ENGLAND Article Open access 10 December 2020 SOCIAL FRAILTY AS A PREDICTOR OF ALL-CAUSE MORTALITY

AND FUNCTIONAL DISABILITY: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS Article Open access 10 February 2024 THE RISK OF SOCIAL ISOLATION AND LONELINESS ON PROGRESSION FROM INCIDENT CARDIOVASCULAR

DISEASE TO SUBSEQUENT DEPRESSION Article 29 April 2025 INTRODUCTION Frailty, social isolation and loneliness are each rising in prevalence and are associated with a range of adverse health

outcomes. Frailty describes a reduction in physiological reserve and increased vulnerability to decompensation due to poor resolution of homeostasis following stressors1,2,3, increasing the

risk of adverse outcomes. These include falls, cardiovascular events, hospitalisation, and mortality1,2,3. There are multiple models of frailty, but two common measures are the frailty

phenotype4 and frailty index5. While these measures were originally developed to assess frailty in older populations (generally > 65 years) several studies have shown that frailty also

predicts adverse health outcomes such as mortality and hospitalisation when applied to younger populations6. The prevalence of frailty rises with age, affecting around 10% of people over 65,

and over a third of those over 807. Frailty is rarer, but does occur, in people in people younger than 65, particularly in the context of high socioeconomic deprivation2,8. Despite this

growing literature, the implications of applying the frailty concept to younger populations have not been widely explored. Both loneliness and social isolation describe aspects of social

vulnerability, the accumulation of numerous, varied social problems with a bidirectional relationship on adverse health outcomes9,10. Loneliness refers to the subjective experience of

feeling alone, i.e., perceived deficits in social connection11, whilst social isolation describes an objective lack of social connections, a condition of not having ties with others12. Like

frailty, social isolation and loneliness are associated with socioeconomic deprivation and with adverse health outcomes13, including (but not limited to) cardiovascular events and mental

health conditions14,15. While loneliness and social isolation have been associated with adverse health and older individuals with high levels of loneliness are at increased risk of

frailty16,17,18, the association between the combination of frailty and social isolation or loneliness with adverse outcomes is less clear10,11,16. Furthermore, the overlap between frailty

and loneliness or social isolation, and their joint associations with socioeconomic deprivation, have not been explored among relatively younger people. This study examines if frailty in

combination with loneliness or social isolation is associated with adverse health outcomes (all-cause mortality and number of hospitalisations), using data from UK Biobank. RESULTS Of the

sample of 502,456 participants in UK Biobank, 461,047 had complete data for frailty, loneliness, and social isolation (mean age 56.5, 251,604 (54.6%) female). Both loneliness and social

isolation were more common among people with frailty (Table 1). Overlap between participants identified by each measure is shown in Fig. 1. Frailty was more prevalent in women than men and

among older participants, while loneliness and social isolation were more common in men and in younger participants (supplementary material). However, all three states were prevalent across

the age spectrum. The combination of frailty and social isolation or loneliness was most common in the context of socioeconomic deprivation (Fig. 2). ASSOCIATION WITH ALL-CAUSE MORTALITY

Hazard ratios for combinations of frailty and loneliness or social isolation and mortality in UK Biobank are shown in Fig. 3. Loneliness was associated with increased mortality risk in

robust and pre-frail individuals, but not in participants with frailty. Social isolation was associated with increased mortality risk at all levels of frailty, compared with no social

isolation, however the effect was smaller in people with frailty compared to pre-frail or robust (_p_-interaction < 0.01). There was no significant interaction with age, suggesting the

relative association with mortality was similar across the age range included. However, on the absolute scale, the increased mortality risk associated with frailty, as well as with social

isolation or loneliness, increased with age (Fig. 4) with only modest absolute increases in risk in people below 60. Findings using the frailty index (without adjusting for multimorbidity)

were similar when assessing loneliness, however social isolation was associated with increased mortality at all levels of frailty. In equivalent models using the frailty phenotype (i.e., not

adjusting for multimorbidity) social isolation was associated with mortality in people with frailty. ASSOCIATION WITH HOSPITALISATION The association between combinations of frailty measure

and loneliness or social isolation, and incident rate ratio for hospital admissions in are shown in Fig. 5. Loneliness was associated with greater hospitalisation risk at all levels of

frailty. Social isolation was associated with increased risk in robust and pre-frail participants but was attenuated in the context of frailty. Using the frailty index, the risk associated

with either loneliness or social isolation was attenuated in participants with frailty. Similar to mortality, the absolute risk of hospitalisation was considerably higher in older people for

a given level of frailty or loneliness/social isolation (supplementary appendix). DISCUSSION SUMMARY OF FINDINGS This analysis assessed the prevalence and impact of frailty in combination

with social isolation or loneliness in UK Biobank participants aged between 37- and 73-years-old. Our findings highlight that frailty is associated with both social isolation and loneliness

among relatively younger people than have been previously studied. Frailty, social isolation and loneliness are all associated with high socioeconomic deprivation: the combination of frailty

with social isolation and loneliness was rare in in more affluent areas, but relatively common in more deprived communities. Finally, frailty, social isolation and loneliness are each

associated with an increased risk of adverse health outcomes including mortality and hospitalisation, however the association between loneliness and social isolation and adverse outcomes was

attenuated in participants with frailty. COMPARISON WITH OTHER LITERATURE The association between frailty and both loneliness and social isolation has been demonstrated across a range of

countries and settings10. Recent systematic reviews estimate that people living with frailty were over three times more likely to experience loneliness and approximately twice as likely to

be socially isolated19,20. The studies in these reviews focussed largely on older populations (typically > 65 years). Our findings demonstrate that these associations hold amongst younger

people. Our study also expands on these previous estimates by assessing the relationship with socioeconomic deprivation, demonstrating that all three constructs are strongly associated with

area-based socioeconomic position and that the combination of frailty with loneliness or social isolation is particularly more common in these settings. Previous studies report that social

vulnerability and frailty are each associated with mortality in older people21,22,23. Most of those studies assessing the combination of frailty and social vulnerability in relation to

mortality have used composite measures such as the social vulnerability index (rather than loneliness or social isolation)22,24, with the exception of one previous study from the

Netherlands11. This analysis builds on these by extending analysis to younger age groups. Our findings indicate that frailty, social isolation and loneliness are each associated with adverse

outcomes in younger people. However, the absolute risk of mortality for a given level of frailty and loneliness or social isolation was considerably higher in older people. In people with

frailty, the association between loneliness or social isolation and adverse outcomes was largely attenuated (after also adjusting for multimorbidity). This finding is similar to Amrstrong

and colleagues who showed that social vulnerability (quantified using a social vulnerability index) was associated with mortality in people without frailty but that in people with a frailty

index > 0.2 this association was similarly attenuated24. One previous study assessed the impact of combinations of frailty and social isolation or loneliness with mortality in a similar

way to this study. Hoogendijk et al. studied frailty and social isolation or loneliness in people aged 65 and older in the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam and, in contrast to this study,

found an increased mortality risk with loneliness or social isolation in the context of frailty11. This difference may reflect a combination of different age ranges, differences in how

loneliness and frailty were specified (the previous study used a binary frail/non-frail categorisation), different analytical choices such as covariate adjustment, or the impact of biases

(such as collider bias) influencing observed associations. Previous studies assessing the risk of hospitalisation associated with frailty and social vulnerability have not assessed

loneliness or social isolation, but rather a composite measure of ‘social frailty’ which encompasses a range of these concepts25,26. Neither of these studies found that ‘social frailty’ was

associated with hospitalisation after accounting for physical frailty. Prevalence of combinations of frailty and loneliness/social isolation is lower than according to previous studies11

which may reflect the relatively younger age of UK Biobank participants, as well as the fact that UK Biobank participants are, on average, more affluent than the general population. Our

finding that loneliness has a greater impact on robust/pre-frail individuals aligns with previous research which found that the association between social vulnerability and mortality was

greatest among the fittest participants24. Previous studies have demonstrated a complex and bidirectional relationship between frailty and both social isolation and loneliness16,19, 27. Our

analysis was not designed to assess these trajectories, or to establish causal relationships between these constructs. Similarly, we cannot claim causal relationships between either frailty,

social isolation or loneliness and mortality or hospitalisation, due to potential for residual confounding, reverse causality, and collider bias. Rather, our findings provide descriptive

evidence that these states affect individuals across a wide age spectrum, co-occur in areas of high deprivation, and may identify people at greater risk of a range of adverse health outcomes

who may potentially benefit from targeted intervention. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS While this analysis used the two dominant frailty measures in the literature, as well as both subjective

and objective indicators of social vulnerability, reducing some of these concepts to two/three questions may be reductive. Furthermore, the variables used to identify loneliness and social

isolation are proxy measures, some of which (such as ‘living alone’ as one indicator of social isolation) may inaccurately identify participants as potentially isolated where they have other

meaningful sources of social connection. Defining social isolation as the combination of at least two of these indicators, and loneliness as the presence of both explicit and implicit

expressions of loneliness, is intended to minimise this limitation. Only baseline values for frailty and social vulnerability were used, however, these states may change over time and we

were not able to assess these changes. Despite adjustments, there may be confounders not controlled for. Reverse causality (e.g., combined frailty and loneliness result from poor health) is

also possible. There is also risk of selection bias (white, affluent participants are overrepresented in UK Biobank) which not only means that prevalence cannot be generalised and risk

estimates may be conservative, but may lead to collider bias, where criteria such as UK Biobank inclusion may bias estimates of relationships between variables28,29. Finally, while mortality

and hospitalisation could be reliably estimated and are clinically relevant, this study may not capture all relevant outcomes. For example, linkage to primary care data was not available

for the full sample and is limited in its utility to identify the number and type of contact with primary care services. As a result, our analysis is limited to unscheduled hospital

admissions, which can be reliably identified and measure acute hospital admissions but is an incomplete measure of overall healthcare utilisation. The impact of frailty, social isolation or

loneliness, particularly among younger people, may be more fully understood by considering a wider range of outcomes such as impacts on employment, community participation, or the

development of long-term health conditions. IMPLICATIONS There is growing interest in interventions to prevent and reduce frailty or to mitigate its impact. Similarly, interventions

targeting social isolation at individual, group, and policy level, with varying degrees of success, are being designed and evaluated and rolled out in a range of settings30. Our findings

that frailty and both loneliness or social isolation frequently overlap, particularly in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation, imply that interventions focusing on one construct (e.g.,

frailty) must actively engage with these other issues (such as social isolation and socioeconomic deprivation) which may be barriers to recruitment, participation, retention or efficacy of

interventions. For example, financial and social barriers associated with deprivation may impact an individual’s capacity to undertake nutritional or exercise-based interventions to improve

frailty. Similarly, physical frailty may impede individuals' participation in group activities designed to improve social isolation. Our findings also indicate that focusing

interventions purely on physical indicators (such as frailty) may neglect people with social vulnerability in less-frail groups who are also at increased risk of adverse health outcomes. The

partial overlap in people identified as living with frailty (by different definitions), loneliness, or social isolation highlights a challenge in identifying these states in practice or as

targets for intervention. Each of these are complex, multi-faceted states. Brief screening tools may have benefit in identifying individuals at risk (e.g. of frailty or loneliness) but may

overlook or exclude some people. Furthermore, integrating identification into routine practice, often within busy and pressured healthcare systems, is challenging given the limited time and

resource available to healthcare professionals and the multiple competing demands faced within healthcare. We would argue that promoting systems that value, resource and prioritise

continuity of care within primary healthcare services are likely to be vital not only to recognising frailty and social vulnerability but to facilitating relational continuity and allowing

for the development of therapeutic relationships responding to this need31,32. Finally, focussing efforts to address frailty purely on people over 65 years old risks neglecting the

substantial minority of people aged under 65 who are living with frailty, most of whom live with high socioeconomic deprivation and many of whom are socially isolated. If frailty is to be

prevented and ameliorated at a societal level, it is necessary to engage actively with this complexity. Such efforts must involve people living with frailty and social isolation, as well as

their wider networks and communities, in designing appropriate interventions. CONCLUSION Frailty, loneliness and social isolation are each associated with increased all-cause mortality and

hospital admission in middle-aged as well as older people, however the risk associated with loneliness and social isolation is reduced in the context of frailty. Frailty and loneliness or

social isolation most frequently coexist among people living with the highest levels of socioeconomic deprivation. Identification of frailty, loneliness and social isolation may provide

important opportunities for intervention. However, to be successful, interventions need to consider the complex challenges which may result from combinations of physical and social

vulnerability, as well as individual and structural barriers associated with deprivation. METHODS PARTICIPANTS From 2006 to 2010, 502,640 UK Biobank participants were recruited by postal

invitation (5% response rate). Participants completed touch-screen questionnaires, interviews, and anthropometric measurements, and gave informed consent for data linkage. UK Biobank has

ethical approval (NHS North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC): 16/NW/0274) and this analysis was performed under UK Biobank Project 14151. As the aim was to assess

combinations of frailty, loneliness or social isolation, participants with missing data relating to these issues were excluded from this study. However, those with missing data on other

baseline data were included in descriptive analyses. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulation (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies

in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines). EXPOSURES Exposures were frailty, which was assessed using frailty phenotype (main analysis) and frailty index (sensitivity analysis), and social

isolation and loneliness. These were assessed using baseline assessment data. FRAILTY PHENOTYPE The phenotype model defines frailty as based on presence of the following factors:

self-reported exhaustion, low grip strength, low energy expenditure, weight loss and slow gait speed. Presence of 3–5 factors constitutes frailty, 1–2 pre-frailty and zero factors classifies

participants as robust4, as per Fried et al.’s frailty phenotype adapted for UK Biobank2. Detailed definitions of each criteria are described in the appendix. The higher of left- and

right-hand grip strength measurements was used for grip strength and other variables were self-reported4. FRAILTY INDEX The frailty index is a count of age-related health deficits (e.g.,

health conditions, symptoms, abnormal laboratory values and limitations) calculated by dividing deficits present in an individual by the total possible deficits to calculate a proportion

between 0 and 1. Frailty is thus seen as the cumulative effect of individual deficits5. Deficits included in this measure were chosen to be those that increase in prevalence with age, are

associated with poor health, and are neither too rare nor too common (i.e. < 1% prevalence in population)33. Deficits were selected based on the frailty index applied to UK Biobank by

Williams et al.34 Participants were then classified as robust (frailty index < 0.12), pre-frail (0.12–0.24), or frail (> 0.24). LONELINESS Loneliness was assessed using two

self-reported measures, based on those in existing scales such as the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale35. These were “Do you often feel lonely?” (no = 0, yes = 1) and “How often are you able to

confide in someone close to you?” (Almost daily to about once a month = 0, once every few months to never or almost never = 1). The two scores were summed and individuals with a score of 2

were classified as lonely. Cut-off is based on previous UK Biobank studies18,36, 37. SOCIAL ISOLATION Social isolation was assessed using three self-reported measures assessing the frequency

of social interaction, “Including yourself, how many people are living together in your household?” (Living alone = 1), “How often do you visit friends or family or have them visit you?”

(Less than once a month = 1) and “Which of the following [activities] do you attend once a week or more often?” (None of the above = 1). Individuals with a score of 2 or 3 were classified as

socially isolated. Cut-off is based on previous UK Biobank studies18,36, 37. OUTCOMES ALL-CAUSE MORTALITY All-cause mortality was identified from linked national mortality records (Public

Health Scotland and Digital Health, England). Median follow-up duration was 11 years. HOSPITALISATIONS Number of hospital admissions classed as urgent or emergency (excluding elective

admissions) were identified via record linkage to the Hospital Episode Statistics. COVARIATES Covariates were selected as potential confounders of the relationship between frailty/social

vulnerability and outcomes. These were based on baseline assessment data and were self-reported. Age and sex were used as recorded. Smoking was categorised as never, previous, or current.

Self-reported alcohol intake as never/special occasions only, 1–3 times per month, 1–4 times per week, or daily/almost daily. Townsend scores were calculated from postcode areas to give an

area-based measure of socioeconomic deprivation38. A count of long-term conditions was calculated based on 43 self-reported long-term conditions. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS All analyses are

reported according to the Strengthening Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement. Analysis was performed using R software (version 4.1.2). For descriptive

analyses, frailty levels (robust, pre-frail and frail) and social isolation (present/absent) or loneliness (present/absent) were cross-tabulated and the number and percentage of participants

with each combination summarised. Associations between each measure and baseline sociodemographic characteristics were also summarised using counts and percentages. Participants were

categorized into groups based on their frailty and loneliness status, or frailty and social isolation status: (1) people without frailty and without loneliness, (2) people with only

loneliness, (3) people with only pre-frailty, (4) people with only frailty, (5) people with pre-frailty and loneliness and (6) people with frailty and loneliness. The same was done for

frailty and social isolation. Weibull models with proportional hazards parameterisation assessed the association between the overlap of frailty and pre-frailty (for both frailty phenotype

and frailty index) and loneliness or social isolation and all-cause mortality, adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, frequency of alcohol consumption, socioeconomic deprivation

(Townsend score), and multimorbidity count. We used parametric survival models to allow us to model the baseline hazard and therefore assess mortality risk on the absolute scale, conditional

on combinations of covariates. Before fitting the models, we plotted log(time) against log(-log(Kaplan Meier estimates)) for strata of each of the model variates showing linear and parallel

lines for each of the covariates. This suggested that Weibull models were an appropriate fit for the data. Separate hazard ratios and 95% confident intervals were calculated for the

combinations of frail and lonely or frail and socially isolated groups, with not frail, not lonely, or not frail, not socially isolated as the respective reference group depending on

combination. Statistical interactions were tested using recommendations by Knol and VanderWeele39 to see if impact of social isolation/loneliness varied depending on level of frailty (and

vice versa) and calculated using the “epiR” R package40. These models were then used to estimate the predicted 10-year risk of mortality conditional on frailty level and loneliness or social

isolation as well as age and sex, in order to assess associations on the absolute scale. Negative binomial regression models were used to model the relationship between frailty and social

isolation or loneliness and number of hospital admissions (adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, frequency of alcohol consumption, socioeconomic deprivation and multimorbidity

count). Models also included an offset term for length of follow-up to account for differential time at risk in participants who died during the follow-up period. Negative binomial models

were selected over Poisson models due to overdispersion of the hospitalisation counts. We also assessed for zero-inflation using Vuong tests. Incident rate ratios and 95% confidence

intervals were calculated for the combinations of frail and lonely or frail and socially isolated groups, with not frail, not lonely, or not frail, not socially isolated as the respective

reference group depending on combination. Analyses were repeated using the frailty index, however models were not adjusted for multimorbidity count as many conditions are also included in

the frailty index. As such, the count of long-term conditions is intrinsic to the frailty index measure (rather than a potential confounder). In post hoc analyses for all-cause mortality, we

also assessed frailty in combination with both loneliness and social isolation. DATA AVAILABILITY The UK Biobank data that support the findings of this study are available from the UK

Biobank (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk), subject to approval by UK Biobank. REFERENCES * Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Rikkert, M. O. & Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. _Lancet_

381(9868), 752–762 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hanlon, P. _et al._ Frailty and pre-frailty in middle-aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and

mortality: A prospective analysis of 493 737 UK Biobank participants. _Lancet Public Health_ 3(7), e323–e332 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hoogendijk, E. O. _et

al._ Frailty: Implications for clinical practice and public health. _Lancet_ 394(10206), 1365–1375 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Fried, L. P. _et al._ Frailty in older adults:

Evidence for a phenotype. _J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci._ 56(3), M146–M156 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rockwood, K. _et al._ A global clinical measure of fitness

and frailty in elderly people. _Cmaj_ 173(5), 489–495 (2005). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Spiers, G. F. _et al._ Measuring frailty in younger populations: A rapid

review of evidence. _BMJ Open_ 11(3), e047051 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * O’Caoimh, R. _et al._ Prevalence of frailty in 62 countries across the world: A

systematic review and meta-analysis of population-level studies. _Age Ageing_ 50(1), 96–104 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Brunner, E. J. _et al._ Midlife contributors to

socioeconomic differences in frailty during later life: A prospective cohort study. _Lancet Public Health_ 3(7), e313–e322 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Andrew,

M. K. Frailty and social vulnerability. _Interdiscip. Top. Gerontol. Geriatr._ 41, 186–195 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hanlon, P. _et al_. The relationship between frailty and

social vulnerability: a systematic review. _Lancet Healthy Longevity_. 5(3), e214–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00263-5 (2024). Article Google Scholar * Hoogendijk, E. O. _et

al._ Frailty combined with loneliness or social isolation: An elevated risk for mortality in later life. _J. Am. Geriatr. Soc._ 68(11), 2587–2593 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Dykstra, P. A. Older adult loneliness: Myths and realities. _Eur. J. Ageing_ 6(2), 91 (2009). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wigfield, A., Turner, R.,

Alden, S., Green, M. & Karania, V. K. Developing a new conceptual framework of meaningful interaction for understanding social isolation and loneliness. _Soc. Policy Soc._ 1–22 (2022). *

Leigh-Hunt, N. _et al._ An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. _Public Health_ 152, 157–171 (2017). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Kuiper, J. S. _et al._ Social relationships and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. _Ageing Res. Rev._ 22, 39–57 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar * Gale, C. R., Westbury, L. & Cooper, C. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for the progression of frailty: The English Longitudinal Study

of Ageing. _Age Ageing_ 47(3), 392–397 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Elovainio, M. _et al._ Association of social isolation and loneliness with risk of incident hospital-treated

infections: An analysis of data from the UK Biobank and Finnish Health and Social Support studies. _Lancet Public Health_ 8(2), e109–e118 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Hakulinen, C. _et al._ Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for myocardial infarction, stroke and mortality: UK Biobank cohort study of 479 054 men and women. _Heart_

104(18), 1536 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kojima, G., Taniguchi, Y., Aoyama, R. & Tanabe, M. Associations between loneliness and physical frailty in community-dwelling

older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. _Ageing Res. Rev._ 81, 101705 (2022). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Kojima, G., Aoyama, R. & Tanabe, M. Associations between

social isolation and physical frailty in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. _J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc._ 23(11), e3–e6 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Amieva, H. _et al._ Social vulnerability predicts frailty: Towards a distinction between fragility and frailty?. _J. Frailty Aging_ 11(3), 318–323 (2022). CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Andrew, M. K., Mitnitski, A. B. & Rockwood, K. Social vulnerability, frailty and mortality in elderly people. _PLOS ONE_ 3(5), e2232 (2008). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Ouvrard, C., Avila-Funes, J. A., Dartigues, J.-F., Amieva, H. & Tabue-Teguo, M. The social vulnerability index: Assessing replicability in predicting mortality over 27 years.

_J. Am. Geriatr. Soc._ 67(6), 1305–1306 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Armstrong, J. J. _et al._ Social vulnerability and survival across levels of frailty in the Honolulu-Asia

Aging Study. _Age Ageing_ 44(4), 709–712 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ament, B. H., de Vugt, M. E., Verhey, F. R. & Kempen, G. I. Are physically frail older

persons more at risk of adverse outcomes if they also suffer from cognitive, social, and psychological frailty?. _Eur. J. Ageing_ 11, 213–219 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Lee, Y., Chon, D., Kim, J., Ki, S. & Yun, J. The predictive value of social frailty on adverse outcomes in older adults living in the community. _J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc._

21(10), 1464–9.e2 (2020). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Davies, K., Maharani, A., Chandola, T., Todd, C. & Pendleton, N. The longitudinal relationship between loneliness, social

isolation, and frailty in older adults in England: A prospective analysis. _Lancet Healthy Longev._ 2(2), e70–e77 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hanlon, P. _et al._ Associations

between multimorbidity and adverse health outcomes in UK Biobank and the SAIL Databank: A comparison of longitudinal cohort studies. _PLos Med._ 19(3), e1003931 (2022). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Batty, G. D., Gale, C. R., Kivimäki, M., Deary, I. J. & Bell, S. Comparison of risk factor associations in UK Biobank against representative, general

population based studies with conventional response rates: Prospective cohort study and individual participant meta-analysis. _BMJ_ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m131 (2020). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mah, J., Rockwood, K., Stevens, S., Keefe, J. & Andrew, M. K. Do interventions reducing social vulnerability improve health in community dwelling older

adults? A systematic review. _Clin. Interv. Aging_ 17, 447–465 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Baker, R., Freeman, G. K., Haggerty, J. L., Bankart, M. J. &

Nockels, K. H. Primary medical care continuity and patient mortality: A systematic review. _Br. J. Gener. Pract._ 70(698), e600–e611 (2020). Article Google Scholar * Khatri, R. _et al._

Continuity and care coordination of primary health care: A scoping review. _BMC Health Serv. Res._ 23(1), 750 (2023). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hanlon, P. _et al._

An analysis of frailty and multimorbidity in 20,566 UK Biobank participants with type 2 diabetes. _Commun. Med._ 1(1), 28 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Williams,

D., Jylhävä, J., Pedersen, N. & Hägg, S. A frailty index for UK biobank participants. _J. Gerontol. Ser. A_ 74, 582–587 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J.,

Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. _Res. Aging_ 26(6), 655–672 (2004). Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Elovainio, M. _et al._ Contribution of risk factors to excess mortality in isolated and lonely individuals: An analysis of data from the UK Biobank cohort

study. _Lancet Public Health_ 2(6), e260–e266 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Elovainio, M. _et al._ Association of social isolation, loneliness and genetic risk

with incidence of dementia: UK Biobank Cohort Study. _BMJ Open_ 12(2), e053936 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mackenbach, J. P. Health and deprivation. Inequality

and the North: by P. Townsend, P. Phillimore and A. Beattie (eds.) Croom Helm Ltd, London, 1987 221 pp., ISBN 0-7099-4352-0, [pound sign]8.95. _Health Policy_ 10(2), 207–206 (1988). Article

Google Scholar * Knol, M. J. & VanderWeele, T. J. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. _Int. J. Epidemiol._ 41(2), 514–520 (2012). Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Stevenson, M., Nunes, T., Heuer, C., Marshall, J., Sanchez, J., Thornton, R. _et al._ epiR: Tools for the Analysis of Epidemiological Data, R

Package Version 0 (2018). Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PH was funded by a Medical Research Council Clinical Research Training Fellowship (Grant reference MR/S021949/1). This research

has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 14151. This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support

(Copyright © (2024), NHS England. Re-used with the permission of the NHS England/UK Biobank. All rights reserved.) This research used data assets made available by National Safe Haven as

part of the Data and Connectivity National Core Study, led by Health Data Research UK in partnership with the Office for National Statistics and funded by UK Research and Innovation. UK

Biobank has ethical approval from NHS North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC): 16/NW/0274. FUNDING This work was funded by the Medical Research Council, Grant Number

MR/S021949/1. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * School of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Clarice Pears Building, Byres Road, Glasgow, UK Marina Politis, Lynsay

Crawford, Bhautesh D. Jani, Barbara I. Nicholl, Jim Lewsey, David A. McAllister, Frances S. Mair & Peter Hanlon Authors * Marina Politis View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lynsay Crawford View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Bhautesh D. Jani View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Barbara I. Nicholl View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jim Lewsey View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * David A. McAllister View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Frances

S. Mair View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Peter Hanlon View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS P.H., M.P., and L.C. designed the study and wrote the analysis plan. B.N. is the data holder under UK Biobank project 14151. MP and PH performed the analysis. M.P.,

L.C., B.D.J., B.N., J.L., D.M., F.S.M. and P.H. interpreted the findings. MP wrote the first draft. L.C., B.D.J., B.N., J.L., D.M., F.S.M. and P.H. reviewed this and subsequent drafts and

approved the final version for submission. M.P., L.C., B.D.J., B.N., D.M., F.S.M. and P.H. had full access to the data. P.H. is the guarantor. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Peter

Hanlon. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate

credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article

are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons

licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of

this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Politis, M., Crawford, L., Jani, B.D. _et al._ An observational

analysis of frailty in combination with loneliness or social isolation and their association with socioeconomic deprivation, hospitalisation and mortality among UK Biobank participants.

_Sci Rep_ 14, 7258 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57366-7 Download citation * Received: 07 September 2023 * Accepted: 18 March 2024 * Published: 27 March 2024 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57366-7 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * Frailty * Social isolation * Loneliness * Mortality *

Hospitalisation