- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The effective dose represents the overall internal radiation exposure to the whole body when exposed to radiation sources. This study aims to compare conventional and software-aided

methods to derive the effective dose. In the present study, 8F-T807 and 18F-Mefway, specific radiotracers for the paired helical tau and serotonin 1A receptor, were administered to healthy

subjects (n = 6, each radiotracer), following which whole-body positron emission tomography (PET) images were obtained for 2 h. Subsequently, time-activity curves for major organs were

obtained, and the residence times were calculated using the “conventional” and “Residence Times model” tools in PMOD software. The residence times from each method was input into OLINDA/EXM

software, and the effective dose was estimated. The differences in the average residence times of the brain, heart, lung, and liver were 18.4, 20.8, 10.4, and 13.3% for 18F-T807, and 17.5,

16.4, 18.1, and 17.5% for 18F-Mefway, respectively. For the mean effective dose, the error rates between the methods were 3.8 and 1.9% for 18F-T807 and 18F-Mefway, respectively. The organs

that showed the greatest difference in the absorbed dose were the urinary bladder for 18F-T807 (40.4%) and the liver for 18F-Mefway (14.1%). This method of obtaining the residence time using

PMOD can be easily used to derive the effective dose, and is applicable in evaluating the safety of radiotracers for clinical trials. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS BIODISTRIBUTION

AND RADIATION DOSIMETRY OF THE POSITRON EMISSION TOMOGRAPHY PROBE FOR AMPA RECEPTOR, [11C]K-2, IN HEALTHY HUMAN SUBJECTS Article Open access 15 January 2021 PRECLINICAL DOSIMETRY MODELS AND

THE PREDICTION OF CLINICAL DOSES OF NOVEL POSITRON EMISSION TOMOGRAPHY RADIOTRACERS Article Open access 29 September 2020 CHARACTERISING 18F-FLUCICLOVINE UPTAKE IN BREAST CANCER THROUGH THE

USE OF DYNAMIC PET/CT IMAGING Article Open access 18 November 2021 INTRODUCTION Positron emission tomography (PET) is a molecular imaging technique that allows the visualization and

quantification of biochemical processes in living organisms1. Its clinical applications are diverse, ranging from the diagnosis of oncological or neurological diseases to monitoring disease

progression and the therapeutic efficacy of certain drugs2,3. Overexposure to ionizing radiation poses a potential risk to patients4. According to the Code of Federal Regulations in the USA,

the effective dose to the whole body should not exceed 30 mSv/administration or 50 mSv/year5. Therefore, it is essential to assess the radiation exposure to the whole body to ensure the

subject's safety from radiation sources in clinical trials. A common method for assessing radiation exposure is internal dosimetry, which involves calculating the absorbed and effective

doses for organs. The absorbed dose quantifies the energy deposited per unit mass from ionizing radiation in materials. Additionally, to determine the relative biological effectiveness of

emitted radiation and the differential sensitivity of organs to radiation-induced stochastic effects, the equivalent dose and effective dose are widely considered6. Imaging-based dosimetry

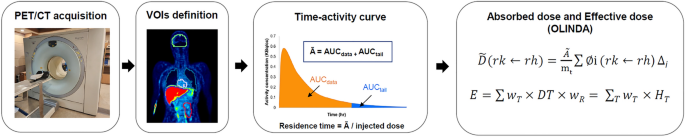

is a highly reliable methodology that is frequently used to assess radiation safety during the development of radiotracers7. As illustrated Fig. 1, conventional dosimetry involves the

acquisition of PET images, determination of the residence time, estimation of the absorbed dose, and calculation of the effective dose8. Among these steps, the calculation of the residence

time is a time-consuming task that involves the following processes: (i) estimation of the radiation exposure, that is, obtaining the time-activity curves (TACs) for major source organs; ii)

calculation of the cumulative activities (\(\widetilde{A}\)) of the source organs by the area under the curve (AUC); iii) division of the cumulative activity by the injected dose to obtain

the residence time. To obtain the cumulative activity, the TAC is integrated using a numerical method. This method involves dividing the AUC into small, finite intervals and estimating the

area of each interval using rectangles or trapezoids within the imaging time windows. Thereafter, the AUC from the final acquisition time point to infinity is calculated by integration using

a decay function that reflects the physical half-life of the specific isotope, and then added to the cumulative activity obtained from the TAC in the regions of interest. PMOD is a software

that analyzes images acquired from various molecular imaging modalities, such as PET, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. Furthermore, it offers user-friendly interfaces

for organ segmentation, facilitating the application of kinetic modeling; hence, it is widely used by researchers to interpret imaging data. Recently, PMOD Technologies developed a Residence

Times model in PKIN that performs dosimetry by automating the calculations for the AUC and residence time with a user-friendly interface. Some researchers have used this model to perform

dosimetric studies on humans. Ikawa et. al., used the Residence Times model of PMOD to calculate the effective dose of 11C-ER-176 for adults, which is a selective PET tracer that targets the

translocator protein 18 kDa. O’Doherty’s groups also used it for 18F-tetrafluoroborate, a specific PET tracer for diagnosing thyroid cancer by targeting the human sodium/iodide

symporter9,10. However, to date, there has been no research to evaluate the effectiveness of PMOD for estimating the residence time compared with the conventional method. Therefore, the

present study aimed to evaluate the quantitative accuracy of the Residence Times model of PMOD by comparing the obtained results with those from conventional methods. METHODS RADIOTRACERS

Two different types of radiotracers were used in this study. 18F-T807 is a specific radiotracer for paired helical tau, and is used to evaluate Alzheimer’s disease. 18F-Mefway is a

radiotracer of the serotonin 1A receptor, which is an imaging biomarker of the serotonergic system. STUDY PROTOCOL To measure the radiation doses of the two PET tracers, we recruited 12

volunteers (3 males and 3 females, that is, 6 subjects for each tracer; Table 1). None of the participants had any medical or neuropsychiatric illness history, and the use of PET tracers in

human subjects was approved by the Institutional Review Board. This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Radioactive Drug Research Committee at the Yonsei

University College of Medicine. All subjects gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the present study. Individual PET data in the present used in previous clinical dosimetry

studies11,12. These studies were performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained

from all subjects involved in the study. PET SCANS After administering 18F-T807 or 18F-Mefway, whole-body PET/CT images were obtained for all the subjects (Fig. 1). These whole-body PET

images were obtained in eight contiguous segments from the vertex of the skull to the middle of the thigh using a Biograph 40 True Point system (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen,

Germany). The acquired time intervals were 0–8 min, 12–20 min, 24–32 min, 40–48 min, 60–68 min, 84–92 min, and 112–120 min for 18F-T807 (233–310 MBq) and 0–16 min, 20–36 min, 40–56 min, 60–

84 min, and 90–114 min for 18F-Mefway (182–274 MBq). Between each time interval, a rest period of 4 min was provided outside the gantry. To correct attenuation and scatter, as well as to

obtain anatomic information, low-dose CT scans (35 mAs, 120 keV, 512 × 512 × 552 matrix, 3 mm slice thickness, 0.6 s rotation time) were performed. All emission data were reconstructed using

ordered subset expectation maximization with 16 iterations. IMAGE ANALYSIS Ten volumes of interest (VOIs) were manually drawn on each coronal slice of the summed PET images with the

assistance of the corresponding CT images. The brain, heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, gallbladder, small intestine, and urinary bladder were used as source organs. The most visible frame was

chosen to draw the region and generate a VOI map. The VOI map was applied to dynamic PET to generate TACs. MATLAB and PMOD software were used for the TAC derivation. Decay-uncorrected TACs

and residence times for the major organs were derived by in-house software written in MATLAB (MathWorks, version 1.1, Vanderbilt University, USA), which we refer to as the conventional

method. In addition, using the same PET data, we obtained the TACs and residence times using the Residence Times model, a dedicated analysis tool in PMOD software (version 3.7. PMOD

Technologies). The residence times obtained using each method were compared. Thereafter, we input the residence time values obtained by each analysis method into OLINDA/EXM software (version

1.1, Vanderbilt University, USA), and then compared the absorbed dose and effective dose of the two radiotracers. RESIDENCE TIME AND RADIATION DOSE CALCULATION CONVENTIONAL METHOD The

cumulative activity was calculated from the AUC of the TACs using an in-house software written in MATLAB (MathWorks). The trapezoidal method was applied to calculate the AUC for each organ,

and the AUC from the last image to infinity was determined by the physical decay of 18F. The residence time, that is, the number of decays per injected activity, was derived by dividing the

AUC by the total injected dose. To determine the residence time for the remainder of the body, the summed residence time for all the source organs was subtracted from the fixed theoretical

value of 2.64 (= T1/2/ln2) for F-1813. OLINDA/EXM was used to derive human organ doses for adult males and females based on the residence times for each source organ. The absorbed dose (D)

can be calculated by dividing the energy absorbed from the target organ by the mass of the target organ (mt), as follows: $${\text{D}} = \frac{{\tilde{A}}}{{m_{t} }}\sum\limits_{i}

{\emptyset_{i} \left( {rk \leftarrow r_{h} } \right)\Delta_{i} }$$ where ∅i is the fraction of the energy emitted by the source organ (h) that is absorbed by the target organ (k), referred

to as the absorbed fraction. A ̃represents the cumulated activity in the source organ and refers to the AUC of the TAC. ∆i represents the equilibrium absorbed dose constant, i.e., the energy

emitted per unit of cumulated activity. The effective dose (E) represents the overall risk to the whole body, calculated by summing the absorbed doses of each organ multiplied by its tissue

weighting factor: $${\text{E}} = \mathop \sum \limits_{T} w_{T } \times D_{T } \times w_{R}$$ where wT is the tissue weighting factor for organ T, DT is the average absorbed dose in organ

T, and wR is the radiation weighting factor used to calculate equivalent dose for different types and energies of radiation. PMOD ANALYSIS The Residence Times model in PMOD enables the

automation of the residence time calculation based on TACs (Fig. 2A). The trapezoidal method was used to obtain the AUC for each organ. Because trapezoidal fitting is more suitable for

delayed clearance form than exponential fitting, it is preferred in the case of rapid clearance. In addition, we checked the isotope toolbox to obtain the AUC from the last frame to infinity

(Fig. 2B). These two simple checks allowed us to immediately derive the residence time of each organ without further calculations. OLINDA/EXM was used to calculate the absorbed dose and

effective dose values, following the same procedure as for the conventional method. For both methods, we assumed that the bladder content volume was constant based on previous

studies14,15,16. RESULTS Six healthy subjects participated in this study, with an average of 56 years old for 18F-T807 and 34 years old for 18F-Mefway. The amounts of radioactivity

administered were 262.5 MBq and 226.0 MBq for 18F-T807 and 18F-Mefway, respectively (Table 1). Figure 3 shows the representative coronal PET/CT images of 18F-T807 (A) and 18F-Mefway (B) over

time. 18F-T807 PET initially shows uptakes in the lungs, heart, intestine, and brain, and is maintained in the liver, gallbladder, and intestine in the later stages. In the case of

18F-Mefway, radioactivity accumulates and is rapidly washed out from the liver, kidneys, and brain, whereas the uptake in the urinary bladder increases over time. Table 2 summarizes the

average residence times of the source organs and the percentage differences calculated using the conventional method and PMOD for the six healthy subjects. For 18F-T807, the error rate

between the two methods in calculating the average residence time decreases in the order of the urinary bladder (80%), gallbladder (37.9%), kidney (27.9%), heart wall (20.8%), brain (18.4%),

liver (13.3%), lungs (10.4%), and small intestine (4.4%). In case of 18F-Mefway, the lungs show the largest difference of 18.1%, followed by the liver/ brain (17.5%), heart wall (16.4%),

small intestine (12.8%), kidney (12.0%), and gallbladder (1.1%). Table 3 summarizes the absorbed and effective doses of 18F-T807 and 18F-Mefway to the source organs. The absorbed dose for

18F-T807 is the highest in the liver and decreases in the order of the lungs, gallbladder, and urinary bladder in both analysis methods. The difference in the absorbed doses between both

methods is large for the urinary bladder wall (49.7%), followed by the thyroid (31.8%) and heart wall (28.4%), and is the smallest in the liver (5.9%). In case of 18F-Mefway, the absorbed

dose decreases in the order of the urinary bladder, liver, and kidney for both methods. The difference in the absorbed doses between both methods is large for the liver (16.0%), brain

(11.8%), and kidneys (10.1%), and is smallest in the pancreas (0.9%). These results indicated that 18F-T807 is primarily excreted through the hepatobiliary system whereas, 18F-Mefway passes

through the renal excretion system. The effective doses of 18F-T807 and 18F-Mefway were estimated as 22.47 and 40.23 μSv/MBq from the conventional method. These values correspond well with

those from PMOD (21.47 and 40.98 μSv/MBq, respectively). For the mean effective dose, the error rates between the methods were 3.8% and 1.9% for 18F-T807 and 18F-Mefway, respectively. In

terms of sex comparison, females showed 4.1% and 1.8% higher effective doses than males for both radiotracers. DISCUSSION The safety and effectiveness of radiotracers must be evaluated to

conduct clinical trials, wherein internal radiation exposure is used as the evaluation parameter for safety. This internal radiation exposure can be calculated through dosimetry.

Specifically, based on dynamic PET data for a specific radiotracer, the residence time for many organs can be obtained, and the effective dose and critical organs are determined based on

this. To derive the residence time, conventionally, a formula designed by researchers was previously used; the process was complex and difficult, resulting in limited accessibility. However,

if PMOD, an image analysis software, is used, this process is simplified (Fig. 4). In the present study, we observed that the difference in the effective doses between PMOD and conventional

methods is below 4% using previously developed radiotracers (i.e., 18F-T807 and 18F-Mefway). The results of this study are expected to be clinically applicable as they can avoid complexity

in the safety evaluation of radioactive drugs. The effective dose is closely related to the safety of patients, and provides crucial information for go/no-go decision-making in clinical

trials. To obtain an accurate estimate of this value, exhaustive data collection is essential. Therefore, a total-body PET scanner, capable of longer-duration data acquisition, can be

superior to the PET scanner with a limited field of view (FOV). Recently, Hu et al., reported that an 8 h dynamic scan using a total-body PET scanner showed an increase in the cumulative

activity in the liver by more than 18.4% compared to a short-duration PET (75 min) scan. Furthermore, they proved that the error rate in the residence time from long and short acquisition

times for the brain, heart, kidney, liver, and lung ranged from 8 to 24%17. However, including our institution, most hospitals are typically equipped with limited FOV PET systems rather than

total-body PET systems. In this case, having patients lie on a bed for a long period is challenging, and their movement could potentially degrade the quality of the images. Therefore, we

evaluated the validity of the Residence Times model of PMOD in dosimetry analysis based on the most widely used PET imaging protocol, i.e., short-duration image acquisition using limited FOV

PET systems. The error rate in the effective doses for both radiotracers was below 4% between the methods. However, despite the high error rates in the residence times for the urinary

bladder, 18F-T807 showed minimal differences in the effective dose. This is due to the physiological characteristics of 18F-T807, which exhibits hepatobiliary excretion. Therefore, 18F-T807

exhibits the pharmacokinetic characteristics of being excreted through the liver, gallbladder, and intestines. Importantly, the role of the urinary bladder in the distribution and

elimination of 18F-T807 is negligible, and it is believed to have a minimal impact on the effective dose. Another hypothesis is that the tissue weighting factor for the urinary bladder is

0.04, which is not relatively high compared to that for other major organs (brain, 0.12; breast, 0.12; lung, 0.12; stomach, 0.12; kidney, 0.12; colon, 0.12). Therefore, the urinary bladder

has a relatively higher resistance to radiation, and contributes lesser to the effective dose compared to other radiation-sensitive tissues. If the urinary bladder has the longest residence

time, the effective dose may be reduced by consuming sufficient water before PET scan, e.g., in a 18F-FDG PET scan. Sex is one of the important factors that can influence radiation

sensitivity owing to physiological differences. The breast and reproductive tissues (e.g., uterus, ovaries) of females are generally more sensitive compared to those of males. Therefore, the

internal distribution and excretion of radiation within females can be different from that in males, and the radiation exposure is generally higher. This is an important factor to consider

during radiation therapy and diagnostic procedures. According to data from Nuclear Information and Resources Services (NIRS), females exhibit a 50% higher incidence of cancer compared to

males who receive the same radiation dose, indicating that radiation may have a more significant impact on females18. Narendran et al. reported that radiation effects exhibit sex-specific

differences, with females displaying higher radiosensitivity compared to males19. In the present study, we observed that the effective doses in females were relatively higher than in males,

and this result was consistent with both, the conventional method and PMOD Residence Times model analysis. Consequently, internal radiation dose assessments can vary based on sex, and for

diagnostic evaluations using 18F-T807 and 18F-Mefway, we recommend limiting long-term usage in females. The present study has several limitations. First, our work is a retrospective study,

and as such, it did not derive S values from individual participants. Second, despite the differences in residence times and absorbed doses between the two analytical methods, the study did

not elucidate the reason or mechanism for the minimal difference in the effective dose. To address this, it may be necessary to conduct individualized S value analyses to examine various

effective calculation factors. Finally, we did not control the subjects’ age, radiotracer injection dose, and degree of hydration before the PET scan. CONCLUSION Evaluating the internal

radiation dose for radiotracers from whole-body dynamic PET is important because it secures the safety of the drug. In this study, PMOD was used in the dosimetry process to evaluate the

residence time more simply and easily than the conventional method. Although the results are not based on data from sufficient subjects, we observed that the difference of the effective

doses for both methods was below 4%. In addition, there would be fewer deviations for PET tracers performing renal clearance than hepatobiliary excretion. These results are expected to be

available to easily evaluate the internal exposure dose of the radioactive follower under development. DATA AVAILABILITY The materials and datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. REFERENCES * Shukla, A. K. & Kumar, U. Positron emission tomography: An overview. _J. Med. Phys._ 31, 13–21.

https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-6203.25665 (2006). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Blake, P., Johnson, B. & VanMeter, J. W. Positron emission tomography (PET) and

single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT): Clinical applications. _J. Neuroophthalmol._ 23, 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/00041327-200303000-00009 (2003). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Cohade, C. & Wahl, R. L. Applications of positron emission tomography/computed tomography image fusion in clinical positron emission tomography-clinical use, interpretation

methods, diagnostic improvements. _Semin. Nucl. Med._ 33, 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1053/snuc.2003.127312 (2003). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Devine, C. E. & Mawlawi, O.

Radiation safety with positron emission tomography and computed tomography. _Semin. Ultrasound CT MR_ 31, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sult.2009.09.005 (2010). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Zhu, W. _et al._ Biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of the enterobacteriaceae-specific imaging probe [18F]Fluorodeoxysorbitol determined by PET/CT in healthy human

volunteers. _Mol. Imaging Biol._ 18, 782–787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11307-016-0946-9 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bolch, W. E., Eckerman, K. F., Sgouros, G. &

Thomas, S. R. MIRD pamphlet No. 21: A generalized schema for radiopharmaceutical dosimetry–standardization of nomenclature. _J. Nucl. Med._ 50, 477–484.

https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.108.056036 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sgouros, G. _et al._ Three-dimensional imaging-based radiobiological dosimetry. _Semin. Nucl. Med._

38, 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2008.05.008 (2008). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Li, T. _et al._ Quantitative imaging for targeted radionuclide

therapy dosimetry—Technical review. _Theranostics_ 7, 4551–4565. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.19782 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ikawa, M. _et al._

11C-ER176, a radioligand for 18-kDa translocator protein, has adequate sensitivity to robustly image all three affinity genotypes in human brain. _J. Nucl. Med._ 58, 320–325.

https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.116.178996 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * O’Doherty, J. _et al._ 18F-tetrafluoroborate, a PET probe for imaging sodium/iodide

symporter expression: Whole-body biodistribution, safety, and radiation dosimetry in thyroid cancer patients. _J. Nucl. Med._ 58, 1666–1671. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.117.192252 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Choi, J. Y. _et al._ Optimization of the radiosynthesis of [18F]MEFWAY for imaging brain serotonin 1A receptors by using the GE TracerLab FXFN-Pro

module. _J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm._ 56, 589–594. https://doi.org/10.1002/jlcr.3067 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shoup, T. M. _et al._ A concise radiosynthesis of the

tau radiopharmaceutical, [18F]T807. _J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm._ 56, 736–740. https://doi.org/10.1002/jlcr.3098 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Constantinescu, C. C., Sevrioukov, E., Garcia, A., Pan, M. L. & Mukherjee, J. Evaluation of [18F]Mefway biodistribution and dosimetry based on whole-body PET imaging of mice. _Mol.

Imaging Biol._ 15, 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11307-012-0582-y (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Dowd, M. T., Chen, C. T., Wendel, M. J., Faulhaber, P. J. & Cooper, M. D.

Radiation dose to the bladder wall from 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose in adult humans. _J. Nucl. Med._ 32, 707–712 (1991). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mejia, A. A. _et al._ Estimation

of absorbed doses in humans due to intravenous administration of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in PET studies. _J. Nucl. Med._ 32, 699–706 (1991). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Thomas, S.

R., Stabin, M. G., Chen, C. T. & Samaratunga, R. C. MIRD Pamphlet No. 14: A dynamic urinary bladder model for radiation dose calculations. _J. Nucl. Med._ 33, 783–802 (1992). CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Hu, P. _et al._ Internal dosimetry in F-18 FDG PET examinations based on long-time-measured organ activities using total-body PET/CT: Does it make any difference from a

short-time measurement?. _EJNMMI Phys._ 8, 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40658-021-00395-2 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Olson, M. _Atomic radiation is more

harmful to women_, <https://www.nirs.org/wp-content/uploads/radiation/radhealth/radiationwomen.pdf> (2011) * Narendran, N., Luzhna, L. & Kovalchuk, O. Sex difference of radiation

response in occupational and accidental exposure. _Front. Genet._ 10, 260. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.00260 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Download

references FUNDING This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences (KIRAMS), the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), Republic of Korea (No.

50461–2023), and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (NRF-2020R1A2C2008618).

AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Young Hoon Ryu and Jae Yong Choi. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Division of Applied RI, Korea Institute of Radiological and

Medical Sciences, 75 Nowon-ro, Nowon-gu, Seoul, Korea Se Jong Oh & Jae Yong Choi * Department of Neurology, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul,

Korea Chul Hyoung Lyoo * Department of Nuclear Medicine, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea Young Hoon Ryu * Radiological and Medico-Oncological

Sciences, University of Science and Technology (UST), Seoul, Korea Jae Yong Choi Authors * Se Jong Oh View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Chul Hyoung Lyoo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Young Hoon Ryu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Jae Yong Choi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS O.S.J., L.C.H. and C.J.Y.: Conceptualization and data

curation. R.Y.H.: Investigation and methodology. O.S.J. and C.J.Y.: wrote the original draft. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS

Correspondence to Young Hoon Ryu or Jae Yong Choi. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer

Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the

original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in

the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your

intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence,

visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Oh, S.J., Lyoo, C.H., Ryu, Y.H. _et al._ Assessing the applicability of PMOD

residence times model for PET image-based radiation dosimetry. _Sci Rep_ 13, 19387 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46822-5 Download citation * Received: 28 May 2023 * Accepted: 06

November 2023 * Published: 08 November 2023 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46822-5 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative