- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT In China, tuberculosis (TB) is endemic and the Bacillus Callmette–Güerin (BCG) vaccine is administered to all the newborns, which may lead to BCG infection in patients with chronic

granulomatous disease (CGD). Infection of BCG/TB in CGD patients can be fatal and pulmonary is the most affected organ. Our objective was to assess the imaging of pulmonary BCG/TB infection

in CGD. We screened 169 CGD patients and identified the patients with pulmonary BCG/TB infection. BCG infection was diagnosis according to the vaccination history, local infection

manifestation, acid-fast bacilli staining, specific polymerase chain reaction, and/or spoligotyping. PPD, T-SPOT and acid-fast bacilli staining were used for diagnosis of TB. Totally 58

patients were identified, including TB (n = 7), solely BCG (n = 18), BCG + bacterial (n = 20), and BCG + fungi (n = 13). The onset of BCG disease was much earlier than TB. For those patients

only with BCG, lymphadenopathy was the first and most prevalent feature. The most found location was the left axilla, followed by the ipsilateral cervical areas and mediastinal or hilar

area. On chest CT, ground-glass opacities, multiple nodules and pulmonary scarring were the most common findings. For TB patients, the pulmonary infections were more serious, including large

masses, severe lymphadenopathy, and extensive pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary infection of BCG were more common than TB in CGD patients, but much less severe. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY

OTHERS IMAGING FINDINGS OF PULMONARY MANIFESTATIONS OF CHRONIC GRANULOMATOUS DISEASE IN A LARGE SINGLE CENTER FROM SHANGHAI, CHINA (1999–2018) Article Open access 09 November 2020 COMPARISON

OF CT FINDINGS AND HISTOPATHOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF PULMONARY CRYPTOCOCCOSIS IN IMMUNOCOMPETENT AND IMMUNOCOMPROMISED PATIENTS Article Open access 05 April 2022 HISTIOCYTIC HYPERPLASIA

WITH HEMOPHAGOCYTOSIS AND ACUTE ALVEOLAR DAMAGE IN COVID-19 INFECTION Article 03 July 2020 INTRODUCTION Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is a primary immunodeficiency disease (PID)

characterized by the deficiency of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase to produce reactive oxygen species. Five types are the most common types according to the

mutation of genes: gp91phox (CYBB) and p22phox (CYBA), the cytosolic subunits p47phox (NCF1), p67phox (NCF2), and p40phox (NCF4)1,2. Patients usually experience recurrent infections caused

by a relatively specific set of catalase positive pathogens, mainly bacterial and fungal infections (Aspergillus, Burkholderia, Nocardia, and Staphylococcus species). In China, tuberculosis

(TB) is endemic and lung is the most affected organ3. In 2015, the incidence of pulmonary TB in children (0–14 years old) of China was 3.03 per 100,0004. To prevent severe TB infection,

Bacillus Callmette–Güerin (BCG) vaccination is routinely administered to every newborn. It is one of the most widely used vaccines in over 150 countries and proved to be safe in

immunocompetent hosts5,6. However, for PID patients including CGD, it will lead to BCG infection7. Most present with local BCG disease, mainly regional lymphadenitis5,6. Disseminated BCG

with CGD is extremely rare but fatal with a mortality rate of 60–80%8,9. So in China, in addition to the commonly pathogens, BCG and TB infection should also be considered in the clinical

work2,10,11,12. We have performed retrospective reviews on the clinical manifestation of CGD patients and identified the high incidence of BCG infection, which can also be found in other

countries in Asia, South Africa and Latin America2,10,11. Patients with BCG and TB infection all present positive in PPD tests and prolonged and recurrent pulmonary infection, which

sometimes hard to be distinguished in the clinical work. Chest CT is the routine exam for GCD patients and can afford useful information for identifying the pathogens13. However, for

pulmonary BCG/TB infection, researches focusing on imaging findings are limited due to the low morbidity. This is the first research to summarize the imaging manifestations of pulmonary

mycobacterial infection and compare the severity between BCG and TB. METHODS SUBJECTS Our institution is a university teaching hospital, and pediatric Allergy and Clinical Immunology

department is a tertiary referral center for patients with PID. From 1999 to 2021, we screened for pulmonary mycobacterial infection in 169 CGD patients with chest CT. The clinical and

imaging data were reviewed. Informed consent forms were signed by the parents and ethics approval was approved by the institutional review board of the institution. All methods were

performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. CGD was diagnosed as described before2,11. The defective respiratory burst was detected by dihydrorhodamine-1,2,3 (DHR)

test. Decreased protein level of gp91 was tested by flow cytometry-based extracellular staining with Moab 7D5, and gene mutations were identified by Sanger sequencing, including _CYBB_,

_CYBA_, _NCF1_, and _NCF2_. Our analysis focused mainly on the imaging manifestations of pulmonary mycobacterial infections. The accompanied infection of other organs was also evaluated.

Mycobacterial infections were diagnosed according to the published papers2,11,14. BCG infection was diagnosis according to the vaccination history, local infection manifestation, and

evidence of acid-fast bacilli staining from pathology, specific polymerase chain reaction, and/or spoligotyping. PPD, T-SPOT and acid-fast bacilli staining were used for diagnosis of TB. PPD

positive was defined as the diameter of > 5 mm after 48–72 h. BCG infection was classified in three groups according to the affected organs and location: (I) local BCG infection:

lymphadenitis near the injection site; (II) regional BCG infection: regional lymphadenopathy or other lesions beyond the vaccination site (e.g., ipsilateral axillary, supraclavicular,

cervical lymph nodes); and (III) disseminated BCG infection: infections in remote sites or proved by blood or bone marrow culture. The results of G ((1–3)-β-d-glucan) tests and GM

(galactomannan) tests were used as evidences for fungal disease. GM index was defined as positive when > 0.5. G index was defined as positive when > 100 pg/ml8. GM test was highly

sensitive to the infection of Aspergillus2. IMAGING MODALITIES All CT studies were performed with conventional techniques on a 64-slice CT (GE Healthcare, Princeton, NJ). Chest protocol

included the following parameters: tube current 80–100 mAs, tube voltage 80–100 kV and gantry rotation time 350 ms, a matrix of 512 × 512, reconstructed width 0.625 mm. Omnipaque (iodine

content 300 mg/mL) was injected at the dose of 1.5–2 ml/kg by power injector at the rate of 0.8–1 ml/s. Reconstructions were made in the coronal and sagittal planes. Two experienced

radiologists analyzed the CT findings. If there were discrepant readings, they discussed and got the common decision. The observers evaluated: consolidation, nodules, ground-glass opacity,

mass, abscess, cavity, tree-in bud opacities, interlobular septal thickening, pulmonary scarring, bronchiectasis, emphysema, pleural thickening, mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy,

axillary lymphadenopathy, chest wall invasion, calcification in the mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes and pulmonary parenchyma. The radiographic definitions were defined by the Fleischner

Society nomenclature15. Consolidation appeared as a homogeneous increase lesion of lung. A nodule was defined as a rounded opacity, well or poorly defined, up to 3 cm in diameter while a

mass more than 3 cm in diameter. Ground-glass opacity was hazy increased opacity in pulmonary parenchyma, with bronchial and vascular margins visible inside. Bronchiectasis was defined as

localized or diffuse dilatation of a bronchus. A cavity presented as a gas-filled space, within pulmonary consolidation, a mass, or a nodule. Emphysema was a focal area of low attenuation,

usually without visible walls. Mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy was defined by the short-axis diameter of the lymph nodes more than 10 mm. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Data were presented in a

descriptive way. Continuous parameters were presented as mean ± standard deviation and inter-quartile range (IQR). Categorized data were expressed as number and percentages. Unpaired

Student's _t_ test was used to compare the age of patients in two groups. The degree of inter-observer agreement was evaluated by Fleiss’ κ values: κ < 0.40, poor agreement; 0.40

< κ < 0.75, fair to good agreement and 0.75 < κ < 1.00, excellent agreement. ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE Informed consent forms were signed by the parents and

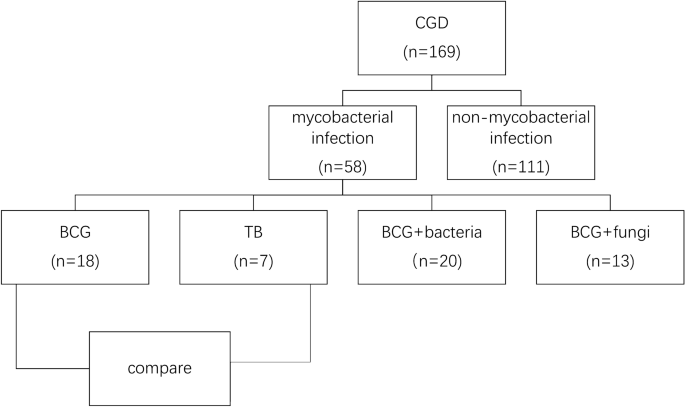

ethics approval was approved by the institutional review boards of the Children’s Hospital of Fudan University. RESULTS DEMOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL FEATURES The flow chart was listed in Fig. 1.

Among all the 169 CGD patients in recent 20 years, 58 patients with pulmonary mycobacterial infection and chest CT examinations were included in this study. Fifty-seven (96.55%) cases were

male, and 1 (3.44%) was female, indicating a high proportion of X-linked CGD. CYBB was identified as the main gene type. Of all the patients, 51 (87.93%) cases presented with BCG infection

and 7 (12.07%) patients with TB. The average stimulation index was similar in both groups. The average age at BCG diagnosis was significantly lower than that of TB (6.33 ± 9.84 month-old vs.

58.14 ± 65.85 month-old, respectively, _p _< 0.05). In BCG group, apart from the patients with other bacterial (n = 20) and fungal (n = 13) infections, 18 patients presented solely with

BCG disease. No other pathogens were found in TB group. The demographic and clinical features of subjects involved in the two groups were listed in Table 1. BCG IMAGING FINDINGS To avoid the

disturbance of bacterial and fungal infection, we only included the 18 patients solely with BCG disease for imaging analysis. For those infected with only BCG (n = 18), local BCG infection

lymphadenopathy was the first and most prevalent feature. The most common site was the mediastinal or hilar (n = 15) (Fig. 2A), the left axilla (n = 18) (Fig. 2B), and the ipsilateral

cervical areas (n = 8). CT revealed a majority of hypodense lesions with slight enhancement. Four cases had abscess formation with ring enhancement and one was accompanied by fistula,

presented as enhanced strips extending to the skin. Twelve had sand-like, streak-like or nodular calcification within the enlarged lymph nodes. Nine patients who had a follow-up CT scan

after antituberculosis therapy (Isoniazid, rifampicin and ethambutol) were found with a decrease in the size of lymphadenopathy and an increase in calcification. As disseminated BCG with CGD

is extremely rare and the chest imaging data are limited, we further summarized the chest CT findings of 18 cases only with BCG disease in detail (Table 2). The presence of ground-glass

opacities, multiple small nodules and short pulmonary scarring was most common among all the 108 pulmonary segments of 18 patients. The imaging showed small bilateral patchy ground-glass

opacities without obvious propensity. 1–3 mm nodular lesions were mainly presented in the lower lobes beneath the pleura (Fig. 2C). Mild local pulmonary scarring was accompanied by slight

tractive bronchiectasis and emphysema. Mass and patchy consolidation were found mostly in the bilateral upper lobes with multiple small cavities less than 3 mm in 2 cases. Small nodular

calcification in the pulmonary parenchymal was identified in 20 segments of 7 patients without predominantly lobar location while one demonstrated chest wall invasion and surrounding

soft-tissue mass (Fig. 2D), which was adjacent to the infectious mass in the left upper lobe. Other visceral involvement included hepatosplenomegaly (n = 5), abscesses in the liver (n = 3),

calcaneus osteomyelitis (n = 1) and enteritis (n = 1) (Fig. 3). In patients with hepatic abscess, contrast-enhanced CT scanning demonstrated the presence of multiple nodules with a central,

low-attenuated mass, most of which were less than 5 mm. Patients with enteritis showed markedly thickened and enhanced intestinal wall on abdominal CT, accompanied by a small amount of

ascites. One child was detected with skeletal infection in the calcaneal. Multiple osteolytic lesions showed periosteal reaction and cortical disruption, all of which regressed following

appropriate anti-tuberculosis treatment. We also have reviewed the 13 patients with BCG and fungal infection (Aspergillus or Candida). The 13 patients all presented with multiple nodules and

infiltrations in a random distribution and halo signs around nodules could be found in 3 patients. In 1 patient with Aspergillus infection, large cavities were found inside the mass without

calcification or air crescent sign. Mild enlargement of mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes (10–15 mm) and slight fibrosis were also identified. TB IMAGING FINDINGS The percentage of all

thoracic lesions in patients with TB infections were compared with BCG in Fig. 4. Larger masses with heterogeneous enhancement and calcification were more common in TB infection with the

biggest up to 5 cm in diameter (Fig. 5A). Six patients were found with more remarkable mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy with higher rate of calcification than BCG infection. Some lymph

nodes fused into masses with caseous necrosis inside and compressed the trachea. One patient was identified with TB granuloma of the bronchial mucosa under bronchoscope, leading to

atelectasis of the right lung (Fig. 5B). CT showed severer bronchiectasis and emphysema in 5 (71.43%) patients due to the extensive pulmonary fibrosis. Two patients developed architectural

distortion of the lung and pulmonary volume reduction, which could not be found in BCG infection (Fig. 5C). Large areas of consolidation were more common in TB than BCG infection while no

tree-in-bud opacities were identified (Fig. 5D). Chest wall invasion was found in 1 patient accompanied with spinal osteomyelitis and paravertebral abscess. The other involved sites included

hepatosplenomegaly (n = 2), kidney abscess (n = 1), right tibiofibular bone and foot osteomyelitis (n = 1), cerebral abscess (n = 1) and enteritis (n = 1) (Fig. 6). The imaging features of

enteritis were similar to BCG infection, including extensive intestinal dilation and thickened intestinal wall on CT. One patient had multiple small cerebral abscesses in the left parietal

and occipital lobes, showing high signal on T1WI and DWI, low signal on T2WI sequence and annular enhancement, indicating the possibility of caseous necrosis. The patient also had

osteomyelitis in the right tibiofibular joint and foot, demonstrating local bone erosions and swelling of the surrounding soft tissue. All patients were treated with multiple-drug therapy

(Isoniazid, rifampicin and ethambutol) and INF-therapy. INTER-OBSERVER CORRELATION Agreement between the two radiologists was strong for determining the main chest CT features. For the

diagnosis of pathogens, the agreement of fungal infections (κ value of 0.89) and BCG infection (κ value of 0.76) was good. There was moderate agreement between TB infections (κ value of

0.52), and weak agreement in the diagnosis of bacterial infections (κ value of 0.38). DISCUSSION BCG vaccine has existed for 80 years and has been proved highly useful in preventing severe

TB infections. In China, neonatal BCG vaccination has become a routine as suggested by the World Health Organization. According to the literature, the incidence of BCG complication is less

than 1% in immunocompetent hosts, most of which are presented as local lymph nodes diseases5,6. However, there are concerns about the safety of BCG among PID patients including CGD. Deffert

reported that in 297 cases of CGD patients with mycobacterial infections, BCG was most commonly identified in 220 (74%) patients, while TB was reported in only 59 (20%) patients16. Francesca

examined 71 patients with CGD from 20 countries and found 31 (44%) patients had TB, and 53 (75%) presented BCG infection14. In a review of 93 cases of CGD in Mexico, 54 (58%) cases

developed BCG infection after vaccine while TB occurred in 27 (29%) patients7. The BCG infection usually occurs in the first decade of life, especially within 1 year after vaccination, much

earlier than the onset of TB17,18. The finding was consistent with previous studies. In the research, BCG has a high incidence of complication and earlier onset than TB, with the earliest

presentation of BCG disease 1 month after birth. The impairment in generation of reactive oxygen species would cause the infection to spread in the lymphatic and the blood system, with the

lymphatic system being most vulnerable to infections12,19. In the cohort, lymphadenopathy, whether regional or disseminated, was the most common feature. BCG in China is administered in the

left arm routinely. The most common location was in the left axillary ipsilateral to the injection site, followed by the ipsilateral cervical areas that develop along the lymphatic system20.

The central abscess and rim enhancement could be regarded as a sign of progress, indicating caseous necrosis. After treatment, serial CT studies have been used to document the resolution of

BCG-related lymphadenopathy, including changes in size and calcification, which are similar to the lymphadenopathy of tuberculosis. Patients with PID usually have more severe BCG infection

than patients without PID. Disseminated BCG involves multiple systems with fatal consequences in most cases18. The incidence is estimated to be 0.59 per 1 million and almost occurs in

children with immunodeficiency disorders21,22. The lung has been proved to be the most common site and may be the first involved visceral organ. However, the lack of typical imaging

characteristics could lead to inaccurate diagnosis23,24,25. Nodules and exudation have been reported as the most common manifestations, and some are characterized by small nodular

calcification in the pulmonary parenchyma and lymphoid nodes26. In the cohort, pulmonary lesions presented multiple manifestations, including granulomas forming pathologically characterized

by multiple nodules and masses mainly in the bilateral lower lobes, bearing similarities with the infection of fungus like aspergillus and candida, while the incidence of calcification is

relatively lower in the fungal infection. The left axillary lymphadenopathy also highly suggests the existence of BCG infection. The regions of ground-grass opacity and consolidation vary

from subtle patches to bilateral multi-segment distribution. Other lesions like interstitial pneumonia and fibrotic changes were local and mild without obvious volume loss. In TB-endemic

countries, children with CGD are at high risk of infection. In Argentina, Hong Kong, and Iran, up to 11%, 54.5%, and 31.7% of patients with CGD were found to have TB infection

respectively26. We also observed a high incidence of TB in our cohort, most of which presented more severe infections than BCG group. Radiologic manifestations varied including heterogeneous

patchy of consolidation, large masses with cavitation, multiple nodules, and obvious lymphadenopathy. Miliary lesion has not been found in our group. Progressive fibrosis with volume loss

and tractive bronchiectasis in the upper lobes occurred in almost 1/3 of patients, much severe than BCG. Lymphadenopathy is another feature of TB, which larger in size and most seen in the

bilateral hilar area. Compared with TB infection, BCG lymphadenitis is more generalized and dispersed. TB mostly affects the elderly, and children below 15 years old only constitute less

than 5% of all cases26,27,28. In the paper, the BCG group has a much younger average age of onset than the TB group. In CGD patients, mycobacterial infection also affects other visceral

organs in a disseminated pattern, with liver and spleen as the most common infected organs29. Hepatosplenomegaly and multiple small abscesses have been observed, unlike the abscess of other

pyogenic infection. Osteomyelitis, central nervous system infection and intestinal involvement have also been reported in the published literatures, but with relatively lower morbidity. The

bone infection of BCG and TB has similar radiographic appearance characterized by osteolytic destruction and periosteal reaction, usually in the epiphysis and metaphysis of the long bone30.

In the small or irregular bones, osteolytic destruction and dilation can be found with soft-tissue swelling31,32. As an attenuated live vaccine, BCG presents lower pathogenicity and better

response to anti-tuberculous treatment than TB. However, BCG has a higher incidence, and BCG disease might be the first sign of CGD caused by mandatory vaccination after birth, earlier than

bacteria or fungi. Therefore, it is suggested that an evaluation of underlying immunodeficiency should be given for infant and children diagnosed as BCG disease33. In addition, for neonate

with a family history of PIDs, BCG vaccination should be delayed until PID is excluded. CONCLUSION In our cohort, the onset of BCG disease was much early than TB, which might be the first

sign of PID. Lymphadenopathy, especially in the left axillary ipsilateral to the injection site and the ipsilateral cervical areas was the most common feature, which may regress and form

calcification after treatment. The pulmonary manifestation of BCG infection was less remarkable than that of TB, but with higher incidence. TB infections in CGD patients usually bear serious

consequences (fibrosis with volume loss and tractive bronchiectasis). The involvements of other systems were also common. For CGD patients, radiologists should be alert to the imaging

features for early recognition of mycobacterial infections. DATA AVAILABILITY The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request. ABBREVIATIONS * CGD: Chronic granulomatous disease * PID: Primary immunodeficiency disease * NADPH: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate * TB: Tuberculosis * BCG: Bacillus

Callmette–Güerin REFERENCES * Matute, J. D. _et al._ A new genetic subgroup of chronic granulomatous disease with autosomal recessive mutations in P40 Phox and selective defects in

neutrophil NADPH oxidase activity. _Blood_ 114, 3309–3315 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhou, Q. _et al._ A cohort of 169 chronic granulomatous disease patients exposed to BCG

vaccination: A retrospective study from a single center in Shanghai, China (2004–2017). _J. Clin. Immunol._ 38, 260–272 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jabado, N. _et al._ Invasive

pulmonary infection due to _Scedosporium apiospermum_ in two children with chronic granulomatous disease. _Clin. Infect. Dis._ 27, 1437–1441 (1998). Article CAS Google Scholar * Tao, N.

N. _et al._ Epidemiological characteristics of pulmonary tuberculosis among children in Shandong, China, 2005–2017. _BMC Infect. Dis._ 19, 408 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Zwerling, A.

_et al._ The BCG World Atlas: A database of global BCG vaccination policies and practices. _PLoS Med._ 8, e1001012 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Krysztopa-Grzybowska, K.,

Paradowska-Stankiewicz, I. & Lutyńska, A. The rate of adverse events following BCG vaccination in Poland. _Przegl Epidemiol._ 66, 465–469 (2012). PubMed Google Scholar *

Blancas-Galicia, L. _et al._ Genetic, immunological, and clinical features of the first Mexican cohort of patients with chronic granulomatous disease. _J. Clin. Immunol._ 40, 475–493 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Li, T. _et al._ Genetic and clinical profiles of disseminated _Bacillus_ Calmette–Guérin disease and chronic granulomatous disease in China. _Front.

Immunol._ 10, 73 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sadeghi-Shanbestari, M. _et al._ Immunologic aspects of patients with disseminated Bacille Calmette–Guerin disease in North-West of

Iran. _Ital. J. Pediatr._ 35, 42 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Winkelstein, J. A. _et al._ Chronic granulomatous disease. Report on a national registry of 368 patients. _Medicine

(Baltimore)_ 79, 155–169 (2000). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ying, W. _et al._ Clinical characteristics and immunogenetics of BCGosis/BCGitis in Chinese children: A 6 year follow-up

study. _PLoS One_ 9, e94485 (2014). Article ADS Google Scholar * Marciano, B. E. _et al._ BCG vaccination in patients with severe combined immunodeficiency: Complications, risks, and

vaccination policies. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 133, 1134–1141 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Mahdaviani, S. A. _et al._ Pulmonary computed tomography scan findings in chronic

granulomatous disease. _Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr)._ 42, 444–448 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Conti, F. _et al._ Mycobacterial disease in patients with chronic granulomatous

disease: A retrospective analysis of 71 cases. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 138, 241–248 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Hansell, D. M. _et al._ Fleischner Society: Glossary of terms for

thoracic imaging. _Radiology_ 246, 697–722 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Deffert, C. _et al._ Bacillus Calmette–Guerin infection in NADPH oxidase deficiency: Defective mycobacterial

sequestration and granuloma formation. _PLoS Pathog._ 10, e1004325 (2014). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rezai, M. S., Khotaei, G., Mamishi, S., Kheirkhah, M. & Parvaneh, N.

Disseminated Bacillus Calmette–Guerin infection after BCG vaccination. _J. Trop. Pediatr._ 54, 413–416 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Afshar, P. S., Siadati, A., Mamishi, S., Tabatabaie,

P. & Khotaee, G. Disseminated _Mycobacterium_ _bovis_ infection after BCG vaccination. _Iran. J. Allergy Asthma Immunol._ 5, 133–137 (2006). Google Scholar * Yang, C. S., Yuk, J. M.

& Jo, E. K. The role of nitric oxide in mycobacterial infections. _Immune Netw._ 9, 46–52 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Rigouts, L. Clinical practice: Diagnosis of childhood

tuberculosis. _Eur. J. Pediatr._ 168, 1285–1290 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Roos, D. _et al._ Hematologically important mutations: The autosomal recessive forms of chronic

granulomatous disease (second update). _Blood Cells Mol. Dis._ 44, 291–299 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Köker, M. Y. _et al._ Clinical, functional, and genetic characterization of

chronic granulomatous disease in 89 Turkish patients. _J. Allergy Clin. Immunol._ 132, 1156–1163 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Shrot, S., Barkai, G., Ben-Shlush, A. & Soudack, M.

BCGitis and BCGosis in children with primary immunodeficiency—Imaging characteristics. _Pediatr. Radiol._ 46, 237–245 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Kido, J., Mizukami, T., Ohara, O.,

Takada, H. & Yanai, M. Idiopathic disseminated Bacillus Calmette–Guerin infection in three infants. _Pediatr. Int._ 57, 750–753 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Kawashima, H. _et al._

Hazards of early BCG vaccination: BCGitis in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease. _Pediatr. Int._ 49, 418–419 (2007). Article Google Scholar * Lee, P. P. _et al._ Susceptibility

to mycobacterial infections in children with X-linked chronic granulomatous disease: A review of 17 patients living in a region endemic for tuberculosis. _Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J._ 27,

224–230 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Howie, S. _et al._ Tuberculosis in New Zealand, 1992–2001: A resurgence. _Arch. Dis. Child._ 90, 1157–1161 (2005). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Lamb, G. S. & Starke, J. R. Tuberculosis in infants and children. _Microbiol. Spectr_. 5 (2017). * Andronikou, S. & Wieselthaler, N. Modern imaging of tuberculosis in children:

Thoracic, central nervous system and abdominal tuberculosis. _Pediatr. Radiol._ 34, 861–875 (2004). Article Google Scholar * Hugosson, C. & Harfi, H. Disseminated BCG-osteomyelitis in

congenital immunodeficiency. _Pediatr. Radiol._ 21, 384–385 (1991). Article CAS Google Scholar * Teo, H. E. & Peh, W. C. Skeletal tuberculosis in children. _Pediatr. Radiol._ 34,

853–860 (2004). Article Google Scholar * Han, T. I., Kim, I. O., Kim, W. S. & Yeon, K. M. Disseminated BCG infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. _Korean J.

Radiol._ 1, 114–117 (2000). Article CAS Google Scholar * Boisson-Dupuis, S. _et al._ Inherited and acquired immunodeficiencies underlying tuberculosis in childhood. _Immunol. Rev._ 264,

103–120 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar Download references FUNDING Natural Science Foundation for the Youth (8210021277). CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2019-I2M-5-002).

AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Qiong Yao, Qin-hua Zhou, Xiao-chuan Wang and Xi-hong Hu. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Radiology, Children’s

Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai, 201102, China Qiong Yao, Quan-li Shen & Xi-hong Hu * Department of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Children’s Hospital of Fudan University,

Shanghai, 201102, China Qin-hua Zhou & Xiao-chuan Wang * Cardiac Center, Children’s Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai, 201102, China Xi-hong Hu Authors * Qiong Yao View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Qin-hua Zhou View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Quan-li Shen

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Xiao-chuan Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Xi-hong Hu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Concept and design: Q.Y. Acquisition of data: Q.Y. and Q.Z. Analysis and

interpretation of data: Q.S. Drafting the article: Q.Y. and Q.S. Revising the article: X.H. and X.W. Final approval of the version to be published: X.H. and X.W. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Correspondence to Xi-hong Hu. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the

source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's

Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not

permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Yao, Q., Zhou, Qh., Shen, Ql. _et al._ Imaging characteristics of pulmonary BCG/TB

infection in patients with chronic granulomatous disease. _Sci Rep_ 12, 11765 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16021-9 Download citation * Received: 30 March 2022 * Accepted: 04

July 2022 * Published: 11 July 2022 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16021-9 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get

shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative