- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Declining oxygen is one of the most drastic changes in the ocean, and this trend is expected to worsen under future climate change scenarios. Spatial variability in dissolved oxygen

dynamics and hypoxia exposures can drive differences in vulnerabilities of coastal ecosystems and resources, but documentation of variability at regional scales is rare in open-coast

systems. Using a regional collaborative network of dissolved oxygen and temperature sensors maintained by scientists and fishing cooperatives from California, USA, and Baja California,

Mexico, we characterize spatial and temporal variability in dissolved oxygen and seawater temperature dynamics in kelp forest ecosystems across 13° of latitude in the productive California

Current upwelling system. We find distinct latitudinal patterns of hypoxia exposure and evidence for upwelling and respiration as regional drivers of oxygen dynamics, as well as more

localized effects. This regional and small-scale spatial variability in dissolved oxygen dynamics supports the use of adaptive management at local scales, and highlights the value of

collaborative, large-scale coastal monitoring networks for informing effective adaptation strategies for coastal communities and fisheries in a changing climate. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED

BY OTHERS INCREASING HYPOXIA ON GLOBAL CORAL REEFS UNDER OCEAN WARMING Article 16 March 2023 OXYGEN DYNAMICS IN MARINE PRODUCTIVE ECOSYSTEMS AT ECOLOGICALLY RELEVANT SCALES Article 03 July

2023 ANTHROPOGENIC EUTROPHICATION AND STRATIFICATION STRENGTH CONTROL HYPOXIA IN THE YANGTZE ESTUARY Article Open access 04 May 2024 INTRODUCTION Ocean deoxygenation is currently one of the

most drastic changes occurring in marine ecosystems1,2. Coastal ecosystems are particularly susceptible, with declines in oxygen level occurring more rapidly along the coast compared to open

ocean ecosystems3,4. Further, the intensity and frequency of deoxygenation is expected to worsen with climate change over time5,6,7,8,9. Oxygen levels in some coastal ecosystems may be

nearing thresholds below which fisheries, biodiversity and ecosystems may collapse1 negatively impacting marine species, populations, ecosystems, and the services they provide humans. In

coastal marine ecosystems, exposure to hypoxia (commonly defined as < 2 mg/L10,11,12,13, can cause direct mortality14,15 or severely impact feeding behavior, movement, growth, and

reproductive processes, and reduce habitat quality for marine species13,16,17,18,19. These impacts can in turn scale up to impacts on populations, community composition, and

fisheries2,10,15,20. Many of these impacts of hypoxia are exacerbated by interactions with other co-occurring stressors. In particular, warm temperatures can increase organisms’

vulnerability to hypoxia by enhancing their metabolic demand for oxygen21,22,23. Hypoxia can also increase vulnerability to the impacts of fishing, as when organisms fleeing from hypoxia

aggregate at edges of low oxygen waters, and are targeted by fishers24. Spatial and temporal patterns of variability in coastal hypoxia can influence their severity and impact on coastal

ecosystems. Larger-scale seasonal drivers of hypoxia such as weather-driven nutrient loading, stratification, water temperatures, and upwelling patterns6,10 can interact with finer-scale

transport processes such as tidal flushing and internal bores to generate complex patterns of temporal variability in dissolved oxygen25,26. These processes can also interact with the

physical structure of nearshore habitats to produce local-scale spatial differences in the severity and temporal patterns of exposure to hypoxia27,28,29. For example, in the Monterey Bay

region of California, USA, regional wind-driven upwelling transports cold, hypoxic deep water up onto the shelf, local internal bores move this hypoxia water into the shallow nearshore in

distinct pulses, and where these internal bores surge and recede along local kelp forest rocky reef topography, hypoxic water can pool in benthic depressions to generate highly localized

(< 10 m) spatial mosaics of hypoxic exposure29,30. Spatial variation in the severity and patterns of exposure to physiological stressors can provide natural refuges for organisms from

large-scale climate impacts. Mobile organisms may be able to respond to spatiotemporal shifts in oxygen conditions by moving to escape hypoxia or even take advantage of periodic hypoxia to

increase predation on less mobile, and therefore more vulnerable prey31 whereas sessile or sedentary organisms often benefit most from persistent refuges32,33. Identifying and harnessing

such refuges, e.g., for the siting of seasonal or permanent fishing protections and restoration projects, has been suggested as a promising strategy for coastal communities and management

agencies to implement climate change adaptation and conservation34,35. However, regional-scale analyses of dissolved oxygen dynamics are still uncommon, particularly in open-coast upwelling

systems, and cross-shelf data on oxygen dynamics are not always particularly useful for the communities and marine resource managers whose interests lie mostly in shallow nearshore habitats.

Continuous, high-resolution observations of dissolved oxygen conditions in coastal upwelling ecosystems, at depths of greatest interest to coastal managers and resource users, remain

lacking at regional scales. Such data are available for the first time in the highly productive California Current upwelling region, thanks to a collaborative, participatory monitoring

network of academic, government, and NGO scientists, as well as fishing cooperatives from California, USA, and Baja California, Mexico. Here we analyse a year-long dataset of dissolved

oxygen and temperature data from kelp forest and rocky reef ecosystems from this regional monitoring network. We document spatial and temporal exposures to hypoxia at multiple locations, as

well as substantial spatial heterogeneity and seasonal variability in dissolved oxygen and temperature dynamics. We highlight potential drivers and consequences of these spatial differences,

opportunities for local adaptation, and the value of collaborative regional monitoring networks in the face of escalating exposure to environmental stressors. MATERIALS AND METHODS We

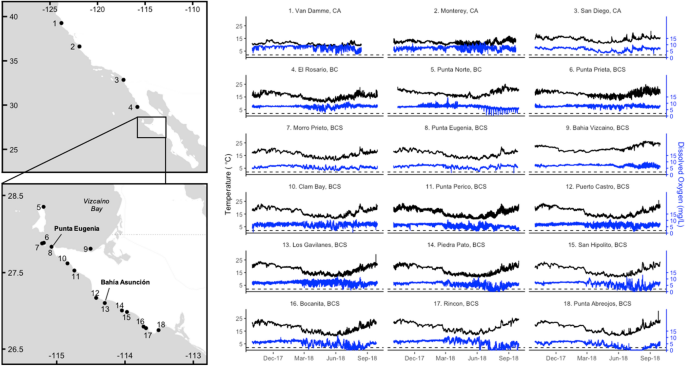

analysed a year of time series data (October 2017–September 2018) for seawater temperature (°C) and dissolved oxygen (DO, mg/L) from the regional network of oceanographic sensors located at

18 sites in kelp forest/rocky reef ecosystems, spanning 13° of latitude from northern California, USA, to central Baja California, Mexico (Fig. 1, Table 1). Most of these sensors were sited,

deployed, and maintained in partnership with local fishing cooperatives from the Federación Regional de Sociedades Cooperativas de la Industria Pesquera (FEDECOOP), the civil association

Comunidad y Biodiversidad in Baja California, and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Deployment sites were all selected on the basis of being known suitable habitat for

ecologically and economically important benthic invertebrate species, particularly red, green, and pink abalone (_Haliotis rufescens_, _H. fulgens_, and _H. corrugata_), which have

previously suffered widespread mortality from hypoxic exposures at sites in this region (Isla Natividad27,36, La Bocana, Micheli et al., unpublished data). Sensors were located at depths of

6 to 15 m (Table 1), falling within the overlapping depth ranges of these abalone species (_H. rufescens_: low intertidal to 40 m; _H. fulgens_: low intertidal to 18 m, _H. corrugata_: 6–30

m37. Other co-occurring valuable benthic fisheries include spiny lobster (_Panulirus interruptus_), sea urchins (_Mesocentrotus franciscanus_ and _Strongylocentrotus purpuratus_), sea

cucumber (_Parastichopus parvimensis_) and turban snails (_Megastraea_ spp.). For all sites except Monterey, temperature and DO were measured using autonomous sensors (PME MiniDOTs and/or

Seabird SBE37-ODO, see Table 1) deployed within 1 m of the bottom, within or directly adjacent to kelp beds. In Baja California and Baja California Sur, sensor locations were selected by

local fishing cooperatives based on their knowledge of present or past productive abalone fishing habitat. At these sites, sensors were deployed and maintained by divers from local fishing

cooperatives, with the support and participation of academic and NGO scientists and staff. The Van Damme and San Diego sites correspond to locations where the California Department of Fish

and Wildlife has conducted long-term abalone population monitoring. Sensors at these two sites were deployed and maintained by scientists and staff from the California Department of Fish and

Wildlife. Sensors at all sites logged measurements at 10-min intervals with the exception of the Van Damme site, which logged measurements at 1-min intervals. At the Monterey site,

temperature and DO were sampled from seawater drawn through the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s intake pipes, located at 17 m and adjacent to kelp forest habitat. Measurements were logged at

intervals of 5 min using wired probes (GF Signet Resistance Thermometer for temperature, In Situ RDO Pro-X for DO) that were cleaned and calibrated regularly. More details of this site,

including intake flow rates are available at25. At all other sites, sensors were cleaned and batteries changed at least once during the 12-month deployment. To maintain identical sampling

intervals across all sites, we filtered the time series data from the Van Damme and Monterey sites to obtain subsets of the data with 10-min intervals between measurements. We used the

temperature and DO time series data to calculate summary statistics to characterize temperature and DO dynamics, as well as hypoxia exposures. We calculated mean and maximum temperature,

minimum DO, coefficient of variation in DO, mean absolute rate of change in DO between adjacent data points, the number of exposures to hypoxic conditions (defined as an exposure to the

widely-used 2 mg/L threshold for hypoxia10,11,12,13 for an hour or more), the mean duration of these hypoxic events, the mean duration between the end of a hypoxic event and the start of the

next one (“return time”), for each monitored site. We calculated mean temperature and DO level for each day of the year and plotted these values on a temperature-DO biplot to visualize

shifts in seawater characteristics throughout the year. For sites that experienced hypoxia, we also took the number of hypoxic events observed for each month of the study and divided them by

the total number of events observed at the site to calculate the proportion of hypoxic events occurring in each month to investigate potential seasonal patterns. To assess the potential

role of upwelling as a driver of dissolved oxygen dynamics across the year, we calculated monthly correlation coefficients between temperature and dissolved oxygen at each site. We assessed

timescales of variability for temperature and DO by calculating variance spectra for the time series data. Power spectra were computed using the Welch method with a Hamming window of 90 days

and a 50% overlap. Spectra were then scaled to the variance in DO. Variances were then integrated across seasonal (0.01–0.05 cycles per day; cpd), synoptic (scales of mesoscale variability

and atmospheric weather patterns, 0.1–0.5 cpd), diurnal (0.75–1.25 cpd), and semidiurnal (1.75–2.25 cpd) period bands, corresponding to 20–100 day, 2–10 day, ~ 24-h, and ~ 12-h cycles

respectively. RESULTS We observed broad regional patterns in exposure to coastal hypoxia throughout the study region. Dissolved oxygen levels fell below the 2 mg/L threshold for hypoxia at

all sites southwest of the Punta Eugenia headland on the Vizcaino peninsula, in Baja California Sur, Mexico (sites 8, 10–18), as well as one site north of this headland, Punta Norte (Fig.

2a). Severely hypoxic (< 0.05 mg/L) conditions were recorded in the five southernmost sites (sites 14–18), south of Bahía Asunción. These five sites also experienced the greatest oxygen

variability (Fig. 2b), the highest number of hypoxic exposure events (Fig. 2d), the longest hypoxia exposure durations (Fig. 2e), and the shortest hypoxia return times of about a day or

less, although they did not also experience distinctly faster rates of change compared to other sites. Among the other sites that experienced hypoxia, mean return times were on the order of

months for Punta Eugenia and Clam Bay, the northernmost sites on the western Vizcaino peninsula, and 1–2 weeks for Punta Perico, Puerto Castro, and Los Gavilanes, the three sites in the

central area of this peninsula (Fig. 2f). Mean return time was about a week for Punta Norte, the only site that experienced hypoxia north of the Punta Eugenia boundary. Despite differences

in sensor deployment depths among sites (6–20 m depth; Table 1), we did not see evidence that these differences impacted our detection of regional patterns of dissolved oxygen dynamics and

exposures to hypoxia. Because exposures to low-oxygen water transported inshore by internal waves may be influenced by closer proximity to deeper offshore sources, we were concerned that

deeper sensors would be more likely to detect lower dissolved oxygen concentrations as well as instances of hypoxia34,35,38. However, hypoxic events were also detected at sites with

shallower sensors, and we only found a weak positive correlation between site sensor depth and the minimum dissolved oxygen recorded at the site (R2 = 0.21, _P_ = 0.03). We did not find any

correlations between sensor depth and the other dissolved oxygen summary variables (_P_ > 0.27 for all variables). We also observed broad-scale patterns for seasonality in temperature and

dissolved oxygen dynamics. Across almost all sites, water temperatures cooled between October and May, during the winter months and upwelling season, and warmed again between June and

September (Fig. 1, S1). At most sites, dissolved oxygen concentrations became much more temporally variable starting in the early spring, when dissolved oxygen levels experienced periodic

decreases (Fig. 1). This led to overall decreases in mean values of dissolved oxygen between spring and summer (Fig. 1, S2). This springtime change was also associated with stronger positive

correlations between water temperature and dissolved oxygen values (Fig. 3). The periodic decreases in dissolved oxygen led to their levels falling below hypoxic thresholds at Punta Norte

and sites south of Punta Eugenia between May and October, but especially in the summer months of June to August (Figs. 1, 4, S2). In the two southernmost sites, Rincon and Punta Abreojos,

water temperature and dissolved oxygen became uncorrelated during these months of hypoxic exposure (Fig. 3, S3d). Exceptions to these broad seasonal trends occurred at sites most closely

associated with the Vizcaíno Bay in Baja California (Punta Norte, Punta Prieta, and Bahía Vizcaíno; sites 5, 6, and 8), which were on average, 1–4 °C warmer than Morro Prieto and Punta

Eugenia, the other two sites in the same area (Fig. 1, S1, S3). At Bahía Vizcaíno, water temperature warmed from January through the spring and summer, and dissolved oxygen levels stayed

high with low variability during the spring (Fig. 1, S1, S2). Punta Norte and Punta Prieta showed temperature patterns similar to most other sites, but dissolved oxygen levels also remained

high and less variable through the spring, relative to Morro Prieto and Punta Eugenia (Fig. 1, S2). Punta Norte experienced a series of regular low-oxygen events in the summer that occurred

at water temperatures higher than the overall site average (Fig. 1, 3, S3). Water temperature and dissolved oxygen were generally not correlated at Punta Norte and Bahía Vizcaíno, but Punta

Prieta showed seasonal correlation patterns similar to most other sites in the region (Fig. 3). Variance spectra for dissolved oxygen showed distinct variance peaks at diurnal frequencies

across all sites, and a semidiurnal peak was also present at many sites (Fig. S5). Integrated variance spectra showed that dominant timescales of variation were similar for temperature and

dissolved oxygen dynamics, with the exception of Punta Norte and Bahía Vizcaíno, where temperature dynamics were dominated by synoptic (2–10 day) variation, while dissolved oxygen dynamics

were dominated by diurnal (~ 24 h) variation. The integrated variance spectra also showed that there could be considerable among-site differences in dominant timescales of variance, even for

nearby sites where broader exposure patterns seem relatively similar (i.e., Piedra Pato and San Hipolito (sites 14 and 15)). DISCUSSION Using data collected from our multi-national

collaborative, participatory oceanographic monitoring network, we found evidence for broad regional and seasonal patterns in water temperature and dissolved oxygen dynamics and exposures to

hypoxia, as well as local-scale differences, across sites spanning 13° of latitude in the southern California Current region. This is the first regional-scale analysis of nearshore dissolved

oxygen dynamics in this highly variable and productive upwelling system. The observed patterns suggest the presence of multiple drivers of hypoxia, and that the vulnerability of coastal

ecosystems and human communities to hypoxia is highly variable seasonally and across multiple spatial scales. Coastal upwelling systems like the California Current region are often

characterized by high variability in temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen. Hypoxia in these systems can be driven by upwelling, alongshore transport of deep hypoxic water, shoaling internal

waves, eutrophication, or a combination of these processes15,25,26,39,40. We found evidence for upwelling as a widespread regional driver of temperature and dissolved oxygen dynamics,

starting in the spring, when most study sites showed decreases in water temperature, increased variability in dissolved oxygen levels, and tighter correlation between temperature and

dissolved oxygen values. These springtime changes correspond to the period of time when upwelling is known to occur in the California Current system, transporting colder, less oxygenated

water into shallower coastal habitats25,41. In addition to the region-scale influences of upwelling, we also found evidence for respiration-driven hypoxia at smaller spatial scales. We

observed further declines in dissolved oxygen levels and longer, more intense exposures to hypoxia at the five sites south of Bahía Asunción in the summer months, accompanied by decreases in

the correlation between temperature and dissolved oxygen. The effect was particularly pronounced at Rincon and Punta Abreojos, which experienced extensive exposures to near-anoxia. At these

two southernmost sites, temperature and dissolved oxygen became decoupled in the summer months, suggesting that upwelling was no longer a key driver of oxygen dynamics. The intense hypoxia

exposures at these southern sites corresponded spatially and temporally to reports of algal blooms (red tide) observations by the fishing cooperatives, which were also corroborated by red

tide detection algorithms based on satellite images (Lee and Micheli, in prep). These cooperatives also reported mortalities of abalone and other benthic invertebrates in their fishing

grounds during this period. This combination of upwelling and respiration drivers cumulatively created a broad latitudinal pattern of hypoxia exposure, with hypoxia exposure mostly occurring

only south of the Punta Eugenia headland, which is a well-known phylogeographic and biogeographic boundary for many taxa42,43. Among these affected sites, southern sites experienced more

intense and extensive hypoxia exposures than northern sites. However, we also found evidence for smaller-scale differences in temperature and dissolved oxygen dynamics, suggesting that more

localized drivers can alter the effects of these large-scale regional drivers. At Bahía Vizcaíno, Punta Norte, and to a lesser extent at Punta Prieta, dissolved oxygen levels remained high

and less variable through the spring initiation of upwelling. These sites are within or oriented towards the Vizcaíno Bay rather than towards the Pacific Ocean and the prevailing wind

direction, and are likely less influenced by wind-driven upwelling. They were consistently warmer than Morro Prieto and Punta Eugenia, the two westward-oriented sites in the same area. The

general lack of correlation between temperature and dissolved oxygen, and the mismatch of dominant variation frequencies at Bahía Vizcaíno and Punta Norte also suggests that dynamics of the

warmer, less-variable Vizcaíno Bay, rather than regional coastal upwelling processes, are the key drivers of conditions at these sites. Similarly, Punta Norte’s unique and highly localized

series of intense exposures to hypoxia in the late summer are likely driven by processes other than upwelling. These hypoxic events were associated with high water temperatures and with

decoupled temperature and dissolved oxygen dynamics, but were also not associated with algal blooms like the ones observed at southern sites. Finally, Punta Prieta appears to exhibit

temperature and dissolved oxygen dynamics intermediate between the Vizcaíno Bay-oriented sites and the Pacific Ocean-oriented sites, likely due to the transport of water by strong tidal

currents that circle the small island of Isla Natividad34,35,44. Because these multiple drivers of dissolved oxygen dynamics and hypoxia exposures act at different spatial scales and are

expected to be impacted differently by global change9,45,46, understanding when and where the drivers differ is critical to anticipating the current and future occurrence and impacts of

hypoxia. Our data show that patterns of exposure and thus, potential ecological vulnerabilities to hypoxia, are highly variable on different spatial and temporal scales, and thus suggest

that the valuable, hypoxia-vulnerable benthic fisheries in the region may be best managed at small spatial scales that match these differences in vulnerability. In Baja California, the

involvement of local fishing cooperatives with ecological and oceanographic monitoring makes such small-scale adaptive management both a practical and desirable strategy47. These fishing

cooperatives have already used data from this monitoring network to make management decisions. Cooperatives in the network independently access and visualize the temperature and oxygen data

at their sites via an application developed by co-author A. Smith on the R Shiny platform48,49. Temperature data have been used to adjust the timing of fishing activities, such as by

delaying the start of the fishing season after prolonged cold temperatures to allow more time for mollusk body conditions to recover after spawning. Oxygen data and documentation of hypoxia

have motivated temporary closures of parts of the fishing grounds, to avoid adding fishing mortality to hypoxia induced mortality. Temperature and oxygen data have also informed the siting

of mariculture, artificial reef and restoration projects in some cooperatives, by enabling identification of sites that are warmer and less prone to hypoxia. Creating similar local capacity

for monitoring and for flexible local-scale adaptive management in other areas is crucial for more effective management and climate change adaptation across the California Current and other

upwelling regions. Our monitoring network has been successful at providing valuable information on spatial variability in hypoxia exposure. However, to evaluate spatial differences in

vulnerability to hypoxia, spatial variation in dissolved oxygen dynamics must be integrated with the hypoxia sensitivity of species and processes in these ecosystems. In this study, we used

the widely-used hypoxia threshold of 2 mg/L as a broad reference point. However, broadly-defined hypoxia thresholds may not be representative of tolerances for this particular system. There

is a very limited amount of hypoxia threshold data available for species in the California Current system. Those that exist for benthic invertebrates suggest that both adult and juvenile

life stages may be tolerant of oxygen levels much lower than 2 mg/L, but that physiological, behavioral, and ecological processes may be impacted at much higher levels of dissolved oxygen

(e.g., 5.5 mg/L in sea urchins)18,50,51. These vulnerabilities also vary among taxa. For example, crustaceans tend to be sensitive to low oxygen conditions while mollusks and echinoderms

tend to be more tolerant13,50. Species mobility will also have an impact on hypoxia vulnerability with sessile benthic organisms being less able to move away from localized hypoxia. A better

understanding of species hypoxia tolerances in this and other systems will be crucial to assessing spatial differences in vulnerability to coastal hypoxia. Furthermore, understanding

potential intraspecific differences in organism tolerances, especially relative to oceanographic and phylogeographic breaks (such as Punta Eugenia in our study region42), will be useful for

assessing the potential for local adaptation. This network of dissolved oxygen sensors has identified broad geographic trends and smaller-scale variability in hypoxia drivers and

vulnerabilities, but further observations will be required to assess the longer-term persistence of these trends in an oceanographic system known for its high temporal variability and

multi-year drivers, and under continuing climate change41,46,52,53. Previous multi-year monitoring has revealed localized high interannual variability and exposures to hypoxia at sites

relatively unaffected during this study period27,36, and respiration-driven hypoxia associated with algal blooms has been reported at the northern California sites in the past, but was not

observed from 2017 to 201854. Although there is evidence that some spatial differences are maintained across years34,35, it is unclear if the broader, regional-scale patterns show similar

levels of persistence. The longevity of this spatial mosaic will determine if and how local- and regional-scale variability in physiological stress can be useful in adaptation, management,

and conservation. Our collaborative, region-wide efforts so far have characterized hypoxia exposures in the important context of seawater temperature. However, dissolved oxygen dynamics

needs to be monitored within an integrated, multi-stressor context. For example, pH is also known to correlate closely with temperature and dissolved oxygen during upwelling events25,55, and

also to influence hypoxia tolerance56. Simultaneous exposures to oxygen, pH and temperature variation and extremes are likely to produce additive, synergistic or antagonistic effects on

organisms57,58. As the first characterization of regional-scale coastal hypoxia dynamics in the California Current upwelling system, this study provides a key step forward in demonstrating

the complex, multiple-driver spatial mosaic of this increasingly important climate change stressor in coastal systems, and also highlights how knowledge co-production in multi-stakeholder

groups can be instrumental in enabling such spatially extensive efforts. Our findings highlight the need for understanding this spatial and temporal variability to design realistic

experiments and models to inform species and ecosystem vulnerabilities, and importantly, providing guidance for local and regional scale adaptive management. In particular, the

identification of potential refuges from hypoxia provides promising opportunities for supporting local resilience through marine protected areas, restoration, and mariculture that leverage

these microclimates27,34,35. The use of large-scale coastal monitoring networks, in partnership with local stakeholders and governments, will be invaluable for meeting this need in the face

of regional and global ocean changes. REFERENCES * Díaz, R. J. Overview of hypoxia around the world. _J. Environ. Qual._ 30, 275–281 (2001). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Laffoley, D.

& Baxter, J. M. (eds) _Ocean deoxygenation: Everyone’s problem. Causes, impacts, consequences and solutions_ (IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, 2019). Google Scholar

* Booth, J. A. T. _et al._ Patterns and potential drivers of declining oxygen content along the southern California coast. _Limnol. Oceanogr._ 59, 1127–1138 (2014). Article ADS CAS

Google Scholar * Gilbert, D., Rabalais, N. N., Díaz, R. J. & Zhang, J. Evidence for greater oxygen decline rates in the coastal ocean than in the open ocean. _Biogeosciences_ 7,

2283–2296 (2010). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Altieri, A. H. & Gedan, K. B. Climate change and dead zones. _Glob. Change Biol._ 21, 1395–1406 (2015). Article ADS Google

Scholar * Breitburg, D. _et al._ Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. _Science (80-)_ 359, eaam7240 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * Keeling, R. E., Körtzinger,

A. & Gruber, N. Ocean deoxygenation in a warming world. _Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci._ 2, 199–229 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Levin, L. A. & Breitburg, D. L. Linking coasts and

seas to address ocean deoxygenation. _Nat. Clim. Change_ 5, 401–403 (2015). Article ADS Google Scholar * Rabalais, N. N., Turner, R. E., Díaz, R. J. & Justić, D. Global change and

eutrophication of coastal waters. _ICES J. Mar. Sci._ 66, 1528–1537 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Diaz, R. J. & Rosenberg, R. Spreading dead zones and consequences for marine

ecosystems. _Science (80-)_ 321, 926–929 (2008). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Hofmann, A. F., Peltzer, E. T., Walz, P. M. & Brewer, P. G. Hypoxia by degrees: Establishing

definitions for a changing ocean. _Deep Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap._ 58, 1212–1226 (2011). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Rabalais, N. N. _et al._ Dynamics and distribution of

natural and human-caused hypoxia. _Biogeosciences_ 7, 585–619 (2010). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Vaquer-Sunyer, R. & Duarte, C. M. Thresholds of hypoxia for marine

biodiversity. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci._ 105, 15452–15457 (2008). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Altieri, A. H. _et al._ Tropical dead zones and mass mortalities

on coral reefs. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A._ 114, 3660–3665 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Grantham, B. A. _et al._ Upwelling-driven nearshore hypoxia

signals ecosystem and oceanographic changes in the northeast Pacific. _Nature_ 429, 749–754 (2004). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kim, T. W., Barry, J. P. & Micheli, F.

The effects of intermittent exposure to low-pH and low-oxygen conditions on survival and growth of juvenile red abalone. _Biogeosciences_ 10, 7255–7262 (2013). Article ADS Google Scholar

* Kolesar, S. E., Breitburg, D. L., Purcell, J. E. & Decker, M. B. Effects of hypoxia on _Mnemiopsis leidyi_, ichthyoplankton and copepods: Clearance rates and vertical habitat overlap.

_Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser._ 411, 173–188 (2010). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Low, N. H. N. & Micheli, F. Lethal and functional thresholds of hypoxia in two key benthic grazers.

_Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser._ 594, 165–173 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Thomas, P. & Saydur Rahman, M. Extensive reproductive disruption, ovarian masculinization and aromatase

suppression in Atlantic croaker in the northern Gulf of Mexico hypoxic zone. _Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci._ 279, 28–38 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Breitburg, D. Effects of hypoxia,

and the balance between hypoxia and enrichment, on coastal fishes and fisheries. _Estuaries_ 25, 767–781 (2002). Article Google Scholar * Brown, J. H., Gillooly, J. F., Allen, A. P.,

Savage, V. M. & West, G. B. Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. _Ecology_ 85, 1771–1789 (2004). Article Google Scholar * Pörtner, H. O. & Knust, R. Climate change affects marine

fishes through the oxygen limitation of thermal tolerance. _Science (80-)_ 315, 95–97 (2007). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Vaquer-Sunyer, R. & Duarte, C. M. Temperature effects

on oxygen thresholds for hypoxia in marine benthic organisms. _Glob. Change Biol._ 17, 1788–1797 (2011). Article ADS Google Scholar * Breitburg, D. L., Hondorp, D. W., Davias, L. A. &

Diaz, R. J. Hypoxia, nitrogen, and fisheries: Integrating effects across local and global landscapes. _Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci._ 1, 329–349 (2009). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Booth, J.

A. T. _et al._ Natural intrusions of hypoxic, low pH water into nearshore marine environments on the California coast. _Cont. Shelf. Res._ 45, 108–115 (2012). Article ADS Google Scholar *

Walter, R. K., Woodson, C. B., Leary, P. R. & Monismith, S. G. Connecting wind-driven upwelling and offshore stratification to nearshore internal bores and oxygen variability. _J.

Geophys. Res. Ocean_ 119, 3517–3534 (2014). Article ADS Google Scholar * Boch, C. A. _et al._ Local oceanographic variability influences the performance of juvenile abalone under climate

change. _Sci. Rep._ 8, 1–12 (2018). Article CAS Google Scholar * DiMarco, S. F., Chapman, P., Walker, N. & Hetland, R. D. Does local topography control hypoxia on the eastern

Texas–Louisiana shelf?. _J. Mar. Syst._ 80, 25–35 (2010). Article Google Scholar * Leary, P. R. _et al._ “Internal tide pools” prolong kelp forest hypoxic events. _Limnol. Oceanogr._ 62,

2864–2878 (2017). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Walter, R. K., Brock Woodson, C., Arthur, R. S., Fringer, O. B. & Monismith, S. G. Nearshore internal bores and turbulent mixing in

southern Monterey Bay. _J. Geophys. Res. Ocean_ 117, 1–13 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Long, W. C. & Seitz, R. D. Trophic interactions under stress: Hypoxia enhances foraging in

an estuarine food web. _Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser._ 362, 59–68 (2008). Article ADS Google Scholar * Kwiatkowski, L. & Orr, J. C. Diverging seasonal extremes for ocean acidification during

the twenty-first centuryr. _Nat. Clim. Chang._ 8, 141–145 (2018). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Safaie, A. _et al._ High frequency temperature variability reduces the risk of coral

bleaching. _Nat. Commun._ 9, 1–12 (2018). CAS Google Scholar * Woodson, C. B. The fate and impact of internal waves in nearshore ecosystems. _Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci._ 10, 421–441 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Woodson, C. B. _et al._ Harnessing marine microclimates for climate change adaptation and marine conservation. _Conserv. Lett._ 12(2), 1–9 (2018).

Google Scholar * Micheli, F. _et al._ Evidence that marine reserves enhance resilience to climatic impacts. _PLoS ONE_ 7, e40832 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Cox, K. W. California abalones, family haliotidae. _Fish. Bull_. 118 28–32 (1962). Google Scholar * Frieder, C. A., Nam, S. H., Martz, T. R. & Levin, L. A. High temporal and

spatial variability of dissolved oxygen and pH in a nearshore California kelp forest. _Biogeosciences_ 9, 3917–3930 (2012). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Mayol, E., Ruiz-Halpern, S.,

Duarte, C. M., Castilla, J. C. & Pelegrí, J. L. Coupled CO2 and O2-driven compromises to marine life in summer along the Chilean sector of the Humboldt Current System. _Biogeosciences_

9, 1183–1194 (2012). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Orellana-Cepeda, E., Granados-Machuca, C. & Serrano-Esquer, J. _Ceratium furca_: One possible cause of mass mortality of

cultured Blue-Fin Tuna at Baja California, Mexico. _Harmful Algae_ 2002, 514–516 (2004). Google Scholar * Bograd, S. J. _et al._ Oxygen declines and the shoaling of the hypoxic boundary in

the California Current. _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 35, 1–6 (2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bernardi, G., Findley, L. & Rocha-Olivares, A. Vicariance and dispersal across Baja

California in disjunct marine fish populations. _Evolution (N Y)_ 57, 1599–1609 (2003). Google Scholar * Haupt, A. J., Micheli, F. & Palumbi, S. R. Dispersal at a snail’s pace:

Historical processes affect contemporary genetic structure in the exploited wavy top snail (_Megastraea undosa_). _J. Hered._ 104, 327–340 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Al

Najjar, M. W. _Nearshore Processes of a Coastal Island: Physical Dynamics and Ecological Implications_ (Stanford University, 2019). Google Scholar * Hughes, B. B. _et al._ Climate mediates

hypoxic stress on fish diversity and nursery function at the land-sea interface. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A._ 112, 8025–8030 (2015). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Sydeman, W. J. _et al._ Climate change and wind intensification in coastal upwelling ecosystems. _Science (80-)_ 345, 77–80 (2014). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Fulton, S.

_et al._ From fishing fish to fishing data: The role of Artisanal Fishers in Conservation and Resource Management in Mexico. In _Viability and Sustainability of Small-Scale Fisheries in

Latin America and The Caribbean_ (eds Salas, S. _et al._) 151–175 (Springer International Publishing, 2019). Chapter Google Scholar * Chang, W., Cheng, J., Allaire, J. J., Xie, Y. &

McPherson, J. shiny: Web Application Framework for R. R package version 1.4.0.2. https://cran.r-project.org/package=shiny (2020). * R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical

computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2020). * Eerkes-Medrano, D., Menge, B. A., Sislak, C. & Langdon, C. J. Contrasting

effects of hypoxic conditions on survivorship of planktonic larvae of rocky intertidal invertebrates. _Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser._ 478, 139–151 (2013). Article ADS Google Scholar * Low, N. H.

N. & Micheli, F. Short- and long-term impacts of variable hypoxia exposures on kelp forest sea urchins. _Sci. Rep._ 10, 1–9 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Bograd, S. J. _et al._

Phenology of coastal upwelling in the California Current. _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 36, 1–5 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Nam, S., Kim, H. J. & Send, U. Amplification of hypoxic and

acidic events by la Nia conditions on the continental shelf off California. _Geophys. Res. Lett._ 38, 1–5 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Rogers-Bennett, L. _et al._ Dinoflagellate

bloom coincides with marine invertebrate mortalities in Northern California. _Harmful Algae News_ 46, 10–11 (2012). Google Scholar * Chan, F. _et al._ Persistent spatial structuring of

coastal ocean acidification in the California Current System. _Sci. Rep._ 7, 1–8 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar * Montgomery, D. W., Simpson, S. D., Engelhard, G. H., Birchenough, S.

N. R. & Wilson, R. W. Rising CO2 enhances hypoxia tolerance in a marine fish. _Sci. Rep._ 9, 1–10 (2019). Article CAS Google Scholar * Boch, C. A. _et al._ Effects of current and

future coastal upwelling conditions on the fertilization success of the red abalone (_Haliotis rufescens_). _ICES J. Mar. Sci._ 74, 1125–1134 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Gobler, C. J.

& Baumann, H. Hypoxia and acidification in marine ecosystems: Coupled dynamics and effects on ocean life. _Biol. Lett._ 12, 20150976 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google

Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was supported by Grants from NSF BioOce (OCE1736830) and NSF-CNH (1212124), and Grants from The Walton Family, Packard and Marisla

Foundations. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife supported the collection of oxygen data in northern California and San Diego, and the Monterey Bay Aquaarium provided access to

their long-term seawater monitoring dataset. We are grateful to the members, staff and directors of the FEDECOOP fishing cooperatives and communities of the Pacific coast of Baja, and to

CONANP staff of the Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve for their participation and support. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Hopkins Marine Station, Stanford University, Pacific Grove,

CA, USA Natalie H. N. Low, Fiorenza Micheli, Giulio De Leo & Alexandra E. Smith * Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, Moss Landing, CA, USA Natalie H. N. Low * Stanford Center for

Ocean Solutions, Stanford University, Pacific Grove, CA, USA Fiorenza Micheli * Sociedad Cooperativa de Producción Pesquera Progreso, La Bocana, Baja California Sur, México Juan Domingo

Aguilar * Sociedad Cooperativa de Producción Pesquera Pescadores Nacionales de Abulón, Isla Cedros, Baja California Sur, México Daniel Romero Arce * Southwest Fisheries Science Center,

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, San Diego, CA, USA Charles A. Boch * Sociedad Cooperativa de Producción Pesquera La Purísima, Bahía Tortugas, Baja California Sur, México

Juan Carlos Bonilla * Sociedad Cooperativa de Producción Pesquera Ensenada, El Rosario, Baja California, México Miguel Ángel Bracamontes * Comunidad y Biodiversidad, La Paz, Baja California

Sur, México Eduardo Diaz, Arturo Hernandez, Alfonso Romero & Jorge Torre * Sociedad Cooperativa de Producción Pesquera Punta Abreojos, Punta Abreojos, Baja California Sur, México Eduardo

Enríquez * Sociedad Cooperativa de Producción Pesquera Buzos y Pescadores de la Baja California, Isla Natividad, Baja California Sur, México Ramón Martinez * Sociedad Cooperativa de

Producción Pesquera Bahía Tortugas, Bahía Tortugas, Baja California Sur, México Ramon Mendoza * Sociedad Cooperativa de Producción Pesquera California San Ignacio, Bahía Asunción, Baja

California Sur, México Claudia Miranda * Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, 94305, USA Stephen Monismith * Federación Regional de

Sociedades Cooperativas de la Industria Pesquera Baja California, Ensenada, Baja California, México Mario Ramade * Coastal Marine Science Institute, Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center,

University of California Davis, Davis, CA, USA Laura Rogers-Bennett * California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Bodega Marine Laboratory, Bodega Bay, CA, USA Laura Rogers-Bennett *

Sociedad Cooperativa de Producción Pesquera Emancipación, Bahía Tortugas, Baja California Sur, México Carmina Salinas * Scoot Science, Santa Cruz, CA, USA Alexandra E. Smith * Sociedad

Cooperativa de Producción Pesquera Leyes de Reforma, Bahía Asunción, Baja California Sur, México Gustavo Villavicencio * COBIA Lab, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA C. Brock Woodson

Authors * Natalie H. N. Low View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Fiorenza Micheli View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Juan Domingo Aguilar View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Daniel Romero Arce View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Charles A. Boch View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Juan Carlos Bonilla View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Miguel Ángel Bracamontes View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Giulio De Leo View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Eduardo Diaz View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Eduardo Enríquez View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Arturo Hernandez View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ramón Martinez View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ramon Mendoza View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Claudia Miranda View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Stephen Monismith View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mario Ramade View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Laura

Rogers-Bennett View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Alfonso Romero View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Carmina Salinas View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Alexandra E. Smith View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jorge Torre View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Gustavo Villavicencio View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * C. Brock Woodson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS F.M, C.A.B.,

G.D., M.R., J.T., and C.B.W. conceived the study, created the regional participatory network for data collection, and obtained the funding for the study. N.H.N.L., F.M., J.D.A., D.R.A.,

C.A.B., J.C.B., M.A.B., E.D., E.E., A.H., R.M., R.M., C.M., L.R.B., A.R., C.S., A.E.S., G.V, and C.B.W. collected and processed the field data. N.H.N.L, F.M., and C.B.W. analyzed the data.

N.H.N.L., F.M., C.A.B., G.D., S.M., L.R.B., and C.B.W. wrote and edited the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Natalie H. N. Low. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The

authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional

affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License,

which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a

link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence,

unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory

regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Low, N.H.N., Micheli, F., Aguilar, J.D. _et al._ Variable coastal hypoxia exposure

and drivers across the southern California Current. _Sci Rep_ 11, 10929 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89928-4 Download citation * Received: 25 September 2020 * Accepted: 26

April 2021 * Published: 25 May 2021 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89928-4 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get

shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative