- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Persuasion is a crucial component of the courtship ritual needed to overcome contact aversion. In fruit flies, it is well established that the male courtship song prompts

receptivity in female flies, in part by causing sexually mature females to slow down and pause, allowing copulation. Whether the above receptivity behaviours require the suppression of

contact avoidance or escape remains unknown. Here we show, through genetic manipulation of neurons we identified as required for female receptivity, that male song induces avoidance/escape

responses that are suppressed in wild type flies. First, we show that silencing 70A09 neurons leads to an increase in escape, as females increase their walking speed during courtship

together with an increase in jumping and a reduction in pausing. The increase in escape response is specific to courtship, as escape to a looming threat is not intensified. Activation of

70A09 neurons leads to pausing, confirming the role of these neurons in escape modulation. Finally, we show that the escape displays by the female result from the presence of a courting male

and more specifically from the song produced by a courting male. Our results suggest that courtship song has a dual role, promoting both escape and pause in females and that escape is

suppressed by the activity of 70A09 neurons, allowing mating to occur. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS A NEURAL CIRCUIT ENCODING MATING STATES TUNES DEFENSIVE BEHAVIOR IN _DROSOPHILA_

Article Open access 07 August 2020 A MODULAR CIRCUIT COORDINATES THE DIVERSIFICATION OF COURTSHIP STRATEGIES Article Open access 09 October 2024 NEURAL CIRCUIT MECHANISMS OF SEXUAL

RECEPTIVITY IN _DROSOPHILA_ FEMALES Article 25 November 2020 INTRODUCTION Mating rituals serve many different purposes, such as attracting potential mates, synchronizing reproduction,

announcing the animal’s species, sex and fitness, persuading the mate to overcome contact aversion1. A prospective mate that is unreceptive to the courtship advances will likely flee the

scene2. In _Drosophila melanogaster_ courtship, the male performs a series of distinct and stereotyped motor programs such as orienting towards the female, following her while extending and

vibrating one wing producing a courtship song, quivering the abdomen, tapping and licking female’s genitals and, finally, attempting copulation3,4,5. During male courtship the female

exhibits behaviours that may be interpreted as rejection responses such as wing flicking, ovipositor extrusion, fending, decamping and kicking6,7,8,9. Although performed at different levels,

rejection behaviours are displayed by both receptive and unreceptive females6,10,11,12,13 and constitute the means by which the female communicates with the male. Thus, receptive females

are thought to temporarily reject the courting male to collect quantitative and qualitative information about him3,9,11,14. Despite the mild rejections, a receptive female will eventually

slow down and open the vaginal plates to induce the male to copulate6,8,12,15. Female locomotor activity is tightly coupled with receptivity since unreceptive flies (either sexually

immature, mated, or manipulated) do not slow down nor pause as much as receptive females6,8,16,17,18,19,20,21. More specifically, receptive females slow down in response to the male’s

courtship song17,18,19,21,22,23,24. The relationship between locomotor activity and song has been mechanistically explored in recent years. Besides auditory neurons22,24,25,26,27, the higher

order pC2 neurons are involved in the regulation of locomotion upon song presentation23, as indicated by the negative correlation of speed and calcium responses of female pC2 neurons to a

song stimulus. Genetic manipulation of pC2 activity indicates that other circuit elements must contribute to the locomotor tuning for the song, since activation of pC2 neurons leads to

multiphasic speed responses and their silencing leads to a correlation between speed and the interpulse interval of the song which is uncorrelated in wild type females. pC1 neurons, which

integrate multiple inputs such as internal sensing of the mating status28 and the male pheromone cis-vaccenyl acetate29, also respond to song29, though how these contribute to a locomotor

response has not been shown. With the goal of understanding the behavioural and neuronal mechanisms of female receptivity, we combined detailed quantitative description of female behaviour

during courtship with neuronal manipulations. These approaches inform each other. While detailed behavioural analysis constitutes a window into brain function as it allows the mapping of

specific sets of neurons or circuits to specific behavioural outputs, the identification and manipulation of neurons involved in receptivity contribute to the dissection of the modular

structure of receptivity. In a female receptivity screen, aimed at identifying brain neurons where higher order receptivity would take place, we identified a group of neurons (line 70A09)

that, when silenced, render the female unreceptive. Specifically, when silencing the 70A09 neurons, sexually mature flies in the presence of a courting male walk faster, pause less and jump

more than control flies, behaviours that are hallmarks of an escape response, which could explain why they are unreceptive. However, even if escape is impeded, they still did not mate.

Furthermore, the increased escape response was specific to the courtship context, as these flies did not increase escape response triggered by general threats, such as a large overhead

looming stimulus. Conversely, acutely activating 70A09 neurons lead to a halt in walking. We further confirmed the requirement of courtship to elicit the escape response by pairing

70A09-silenced females with males that do not court. Finally, we showed that the courtship song is key to elicit escape. In summary, we identified a new role of the male courtship song in

eliciting female escape and a set of neurons in the female brain that are involved in suppressing such courtship song-induced escape response. We propose that the male song has a dual role,

first eliciting escape and providing the female with enough time to assess the male, until the decision to mate is made, upon which then the song prompts a decrease in locomotion and that

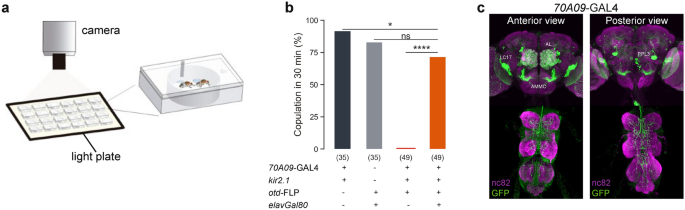

activity in 70A09 neurons is necessary to suppress the initial song-induced escape. RESULTS SILENCING _70A09_-GAL4 BRAIN NEURONS REDUCES FEMALE RECEPTIVITY In order to identify neurons

involved in female receptivity, we performed a silencing screen of the Janelia GAL4 line collection30. Silencing was achieved with the expression of an inward rectifier potassium channel,

_Kir2.1_31, that reduces the probability for an action potential to occur by hyperpolarizing the neurons. To prevent developmental lethality, silencing was restricted to the adult stage

using temperature sensitive GAL8032 which inhibits the expression of _Kir2.1_. The control flies have the same genotype but a different temperature treatment, though all flies were tested at

25ºC (see methods). We tested 1042 lines for fertility and identified 65 lines in which at least 25% of the silenced females did not produce progeny (n = 20–25). Next, we tested these lines

for receptivity. For this, we paired a single wild type naïve male and a silenced virgin female in an arena and quantified copulation within 30 min (Fig. 1a). With this secondary screen we

identified 20 lines that affected receptivity when silenced (Table S1). Finally, we selected eight lines based on the strength of the phenotype, absence of neurons known to affect

receptivity, such as, sex-peptide sensing neurons33,34,35, and confirmation that the phenotype results from neuronal disruption using _elav-GAL80_ (see below). We next retested these lines

while restricting the neuronal manipulation to the brain using a flippase under the control of the orthodenticle promoter _(otd_)36. The lines 70A09 and 57G02 showed a marked reduction in

copulation when brain neurons were silenced in the adult female (Figure S1). All statistical details related to main Figures and Supplementary Figure are shown in Tables S2 and S3,

respectively. The line 70A09 was selected for further analysis considering the more restricted expression pattern when compared to 57G02 (data not shown). The loss of receptivity when

silencing neurons labelled by the line 70A09 (Figure S1) was confirmed with constitutive silencing where no temperature treatment is applied (Fig. 1b). In this case, the controls are the two

parental lines (lines used in the cross to obtain the test flies) crossed with the line w1118 which was the basis for the generation of all the transgenic lines in this work, therefore

providing a neutral genetic background. Constitutive silencing was used in the subsequent experiments of this work because it is not lethal and it involves simpler and faster husbandry

compared to conditional silencing. To confirm that the observed phenotype was a consequence of neuronal disruption we used _elav-GAL80_34 to prevent _Kir2.1_ expression in neurons. We did

not observe abolishment of receptivity in these females (Fig. 1b), indicating that the reduced receptivity is a result of neuronal silencing. Immunostaining of the _70A09-GAL4_ brain neurons

revealed many neuronal groups that could play a role in female receptivity (Fig. 1c). To identify the neurons responsible for the receptivity phenotype observed, we used two approaches that

involved intersections with 70A09. In both approaches, in-house generated splitGAL4 and a LexA version of 70A09 were used to allow for more flexibility in the intersections (Figure S2). One

approach was to generate intersections that separately label each of the groups of neurons that can be identified in the immunostaining. Using this approach, we labelled and tested (i) the

auditory sensory neurons (Figure S3a), (ii) the local GABAergic antennal lobe neurons (Figure S3b), (iii) neurons that express the insulin-like peptides in the pars intercerebralis (Figure

S3c), (iv) the lobula columnar neurons (LC17) (Figure S3d) and (v) the protocerebral posterior lateral cluster (PPL3) (Figure S3e). None of the separate groups recapitulated the _70A09-GAL4_

(from here on referred to as 70A09) silencing phenotype. The second approach was to intersect the 70A09 line with lines of genes involved in generating sexually differentiated circuits,

_fruitless_ (_fru_) and _doublesex_ (_dsx_)9. Immunostaining of the intersection of 70A09 with _fru_ shows labelling of local antennal neurons and auditory sensory neurons, corresponding to

the GABAergic neurons of the 70A09 line (Figure S3f and S3b). Some additional labelling is observed in the protocerebrum corresponding to neurons located in the ventral nerve cord (VNC) that

project to the brain since the intersection in this case is not restricted to the brain. The _fru_ intersection line was not tested further since _fru_-positive brain neurons were shown in

the first approach to not be involved in the receptivity phenotype (Figure S3a, b and f) and the _fru_-positive ascending neurons are out of the scope of this work. Silencing _dsx_-positive

70A09 (70A09⋂_dsx_) neurons does lead to a reduction of receptivity (Figure S3g). Immunostaining of this intersection (Figure S3g) showed labelling of pC1 neurons which had been shown to

modulate receptivity15,29. In fact, the degree of reduction in receptivity resembled that observed by Zhou et al.29. However, this reduction in receptivity is partial and does not explain

the complete abolishment of receptivity observed in the 70A09-silenced females hence other neurons must be involved. The candidates are smaller cells with diffuse innervation which remain

untested. In summary, 70A09 labels brain neurons involved in female receptivity which include but are not restricted to pC1 neurons. 70A09-SILENCED FEMALES ESCAPE IN RESPONSE TO MALE

COURTSHIP To characterise the behaviour of 70A09-silenced females during courtship, we now used a setup that allows tracking the flies (Fig. 2a). We analysed flies’ behaviours from the start

of courtship up to 10 min or until copulation (in those cases where copulation occurred in less than 10 min). We recorded single pairs for 20 min or until copulation to account for

variability in latency to court (Fig. 2b). First, we tested the female receptivity phenotype to validate the use of the setup. We observed that receptivity is also abolished in the arena

with a different size, shape and lighting (Fig. 2c). To confirm that the reduced copulation rate is due to reduced receptivity rather than reduced attractiveness of the female, we measured

the courtship elicited by these females. We observed that males take about the same time to initiate courtship and court at the same levels silenced and control females (Fig. 2b and d).

Female locomotor activity is one of the most reliable indicators of the female’s willingness to copulate6,8,16,17,18,19,20,21, therefore we measured walking speed and pausing levels. Given

that courtship happens in bouts, we quantified walking speed in three distinct moments of courtship dynamics, represented in Fig. 2e: before courtship starts, during courtship (‘courtship

ON’), and during intervals between courtship bouts (‘courtship OFF’). Quantification of walking speed during courtship ON revealed that 70A09-silenced females walk at a substantially higher

speed than control females (Fig. 2f). It is known that unmanipulated females slow down during courtship6,8,16,17,18,19,20,21. Thus, the difference in walking speed during courtship could

result from silenced females not responding to male courtship, i.e., not slowing down like control females. To address this, we compared walking speed during courtship ON with other moments.

We observed that rather than sustaining the speed, 70A09-silenced females increase walking speed during courtship ON compared to before courtship (Fig. 2g). The increase in speed is acute

since, during courtship OFF, 70A09-silenced females return to the walking speed exhibited before courtship. This observation is in sharp contrast with control females that reduce the walking

speed during courtship ON and sustain this reduced speed during courtship OFF. Next, we analysed female pausing as it has been reported to increase during courtship8,17. We found that

70A09-silenced females pause less during courtship compared to control females (Fig. 2h). Comparing across different courtship moments we found that, contrary to courtship ON moments,

pausing increases in courtship OFF (Fig. 2i). The increase in walking speed and reduced rest are means for the female to escape the male. A third way to escape the male is to take off in

flight, which in an enclosed arena results in a jump. For this reason, we investigated whether jumping was affected in manipulated flies. Indeed, during courtship ON 70A09-silenced females

jump more than control flies (Fig. 2j). Jumping in 70A09-silenced females is strongly increased during courtship ON compared to before courtship (Fig. 2k). During courtship OFF jumping

decreases though not significantly, suggesting that the females remain aroused. In the previous section we have shown that the receptivity phenotype was partially due to 70A09⋂_dsx_ neurons.

To test whether this subset of 70A09 neurons is also involved in the escape phenotype, we tested the 70A09⋂_dsx_ silencing in the tracking setup. Analysis of walking speed, pausing and

jumping shows that 70A09⋂_dsx_-silenced females do not escape a courting male (Figure S4). In other words, _dsx_ neurons within the 70A09 line are not involved in the courtship-induced

escape phenotype. Altogether, our findings suggest that activity in 70A09 neurons is required for females to suppress escape responses during courtship. SILENCING 70A09 NEURONS DOES NOT

INCREASE ESCAPE RESPONSES UPON THREAT To determine if 70A09 neurons are involved in general escape responses, we tested the response of 70A09-silenced females to looming stimuli. When

exposed to looming in an enclosed arena, fruit flies have been shown to display different defensive responses, namely freezing, running and jumping37,38,39,40. To analyse escape responses,

i.e. running and jumping, of 70A09-silenced females, we adapted a previously established behavioural paradigm (Fig. 3a)40. Single flies were transferred to a covered arena and allowed 2 min

to explore. This baseline period was followed by 5 min during which the flies were exposed to 7 repetitions of a looming stimulus, displayed on a computer monitor angled above the arenas

(Fig. 3a). To examine the profile of escape responses, we plotted the average speed of the flies aligned to looming onset (Fig. 3b). We found that the speed was constant and similar between

unmanipulated and silenced flies before stimulus onset. Upon looming onset, flies showed a sharp decrease in their speed, which was followed by a rapid increase in locomotion that was less

pronounced for silenced flies. The elevation in speed relative to that observed before looming onset was more noticeable for control flies than for 70A09-silenced females. To better

characterise this disparity in escape responses, we quantified the difference in speed (delta speed) between a defined time window (0.5 s) after looming offset and before looming onset (Fig.

3c). We found that the increase in speed in response to looming stimuli was significantly lower for 70A09-silenced females compared to controls. The less vigorous escape responses observed

for silenced females in response to threat differ from what was observed in the context of courtship. In response to a courting male, besides increased walking speed and reduced pausing,

silenced flies also show an increase in jumps, that likely correspond to take-off attempts. Therefore, we also investigated jumping responses upon visual threat. We quantified the number of

escape jumps per fly for the different genotypes during the baseline and stimulation periods (Fig. 3d). During the stimulation period, silenced females jumped significantly more than both

controls. However, we found that during baseline silenced females also jumped significantly more than unmanipulated females. Given this result, we asked if the increase in jumps observed

during stimulation relative to those observed in baseline was significantly higher for silenced females. For each genotype, we calculated the difference between the number of jumps observed

during stimulation and baseline (delta jumps) (Fig. 3e), and we found a significant difference between the silenced condition and only one of the controls. Together, these results indicate

that the increased escape displayed by 70A09-silenced females in the context of courtship is a specific response to the courting male, not observable in a general threat context.

70A09-SILENCED FEMALES ARE UNRECEPTIVE INDEPENDENTLY OF ESCAPE AVAILABILITY The increased walking speed of 70A09-silenced females during courtship raises the question of whether the absence

of mating is merely a consequence of the inability to slow down. To address this question, we restricted the walking space of the arenas used for screening with the introduction of an

adapter (restricted arenas, Fig. 4a). In this new version the space is 6 mm × 5 mm × 4.5 mm, which allows movement but not running (consider for reference that a fly is around 2 mm long). We

paired single flies for 20 min and analysed for up to 10 min after courtship initiation. We confirmed that indeed in these arenas 70A09-silenced females do not speed up but rather walk at

similar speed of control females (Fig. 4b). We found that, in this context, silenced females still did not mate (Fig. 4c). The male courtship index is similar in all conditions showing that

the difference in copulation rate does not result from low male drive (Fig. 4d). In sum, our results show that 70A09 females are unreceptive independently of their ability to escape.

COURTSHIP, AND SPECIFICALLY COURTSHIP SONG, IS REQUIRED FOR 70A09-DEPENDENT ESCAPE SUPPRESSION To confirm that increase in walking speed, reduction in pausing and increase in jumps in

70A09-silenced females is a response to courtship we paired female flies with _fru_ mutant males that do not court41. Since courtship was absent, we used the distance between the flies as a

proxy for courtship as we have previously shown that below 5.5 mm there is a 95.5% likelihood of courtship (‘courtship distance’)16. We observed no difference between the walking speed of

70A09-silenced females and control females at courtship distance (Fig. 5a), as well as, no difference in walking speed between courtship distance and not courtship distance for all

conditions (Fig. 5b). These results indicate that the changes in female walking speed require courtship from a male, the mere presence of a male not being sufficient to trigger them. Pausing

levels were also very different from those observed in females paired with a courting male. At courtship distance, silenced flies pause either as much or more when compared to the parental

controls (Fig. 5c). In all conditions there is more pausing at courtship distance (Fig. 5d). Finally, jumps were nearly absent in all conditions (Fig. 5e and f). From our results, we

conclude that a courting male and not the mere presence of a male triggers escape in 70A09-silenced females. A courting male produces different stimuli that may lead the female to escape.

They could be the visual stimulus of an approaching animal, the scent of male pheromone or the song that the male produces with wing vibration. Given that song has been shown to modulate the

speed of the female during courtship, albeit to reduce it17,19,21,22,22,23,24, we decided to test the role of song in the response of 70A09-silenced females. For this, we paired

70A09-silenced females with wild type males that were either intact or with the wings removed (‘wingless’). We first confirmed that courtship index is not affected by wing removal (Figure

S5). We then analysed the female walking speed in the two different conditions. We found that, during courtship, the walking speed of 70A09-silenced females was lower for females paired with

wingless males (Fig. 5g). During the different moments of courtship, the walking speed of females paired with wingless males never changed whereas control silenced females with intact

males, as previously found (Fig. 2f), increased their walking speed during courtship ON moments compared to courtship OFF moments (Fig. 5h). In this experiment, however, the walking speed of

70A09-silenced females with intact males is not significantly different between baseline and courtship ON moments (Fig. 5h), unlike what was previously found (Fig. 2f), which may be a

reflection of a trend for higher baseline walking speed observed in this experiment when compared to the previous experiment (Mann–Whitney U, U = 623, p = 0,0516). Analysis of pausing during

courtship ON revealed that 70A09-silenced females paired with wingless males pause more than those paired with intact males (Fig. 5i). Across the different moments of courtship

70A09-silenced females paired with wingless males have similar pausing levels with a small increase of pausing in courtship OFF compared to before courtship (Fig. 5j). Finally,

70A09-silenced females paired with wingless males jump very little during courtship ON (Fig. 5k) or any other moment of the video (Fig. 5l) whereas 70A09-silenced females paired with intact

males significantly increase jumps during courtship ON compared to before courtship with no significant difference in courtship OFF moments. These results clearly show that a courting male

that is unable to produce song does not elicit any type of escape in 70A09-silenced females, i.e., that song is a trigger for escape in 70A09-silenced females. ACTIVATION OF 70A09 NEURONS

LEADS TO FEMALE PAUSING BUT NOT MATING Silencing 70A09 neurons leads to decreased receptivity, which is accompanied by increased escape (higher walking speed, less pausing and more jumping)

during courtship. We sought to explore the effect of activating these neurons during courtship. To this end, we expressed the red shifted channelrhodopsin, csChrimson42 in 70A09 neurons. We

recorded single pairs of courting flies for 9 min. The red light was off during the first 3 min, it was turned on from minute 3 to 6 and was again off for the last 3 min in order to allow

within-video comparisons. In this experiment, we quantified speed which includes pausing and jumping (as opposed to walking speed which does not). We observed that upon light activation the

test flies drastically reduced their speed while the speed of control flies was unchanged (Fig. 6a and b). In fact, activated females paused during light on, only performing lateral

displacement prompted by the courting male (Movie 1). Once the light was off, activated females recovered their speed to values similar to those prior to activation as shown by comparing the

delta of the speed during lights off and baseline to a database with a random group of values with a similar range varying around zero (Fig. 6c). Given that silencing 70A09 neurons reduces

receptivity, we wondered what would be the effect of activation of these neurons on receptivity. Analysis of the latency to copulate shows that activated flies did not mate during light on

and resume mating once the light turns off whereas control females mate throughout the whole video, indicating that activation of 70A09 neurons leads to a reduction of receptivity (Fig. 6d).

Courtship remains high throughout the experiment (Figure S6). It is unclear whether it is activation and silencing of the same or a different set of neurons within the 70A09 expression that

leads to loss of receptivity. With these experiments we found that, in terms of speed, activation of 70A09 neurons leads to the opposite phenotype of silencing them during courtship ON. We

speculate that in wild type receptive females these neurons are gradually activated during courtship ultimately leading to female pausing. DISCUSSION Courtship allows animals to display and

evaluate their qualities before they choose a mate. In most species, males initiate courtship and females decide whether or not to mate43. Reproductive decisions have a powerful impact in

the survival of the species and thus the communication between courtship partners is vital. To understand courtship behaviours, we must focus on how the partners communicate which sometimes

involves subtle cues. Here we reveal a novel layer of regulation of female speed in the context of courtship. Specifically, we found that escape suppression is a fundamental and hitherto

unknown step of the female’s response to courtship. When modulation of the 70A09 is absent, females escape the courting male continuously and vigorously. One could assume that these females

are not able to perceive courtship from the male, perceiving instead an approaching animal, which would lead them to escape. But in fact, these females are recognizing the courtship song and

this stimulus is inducing escape. Our work suggests that part of the female brain is interpreting song as aversive while another part processes song as a signal to slow down. We propose

that activity in 70A09 brain neurons tips the scale to slowing down. Escape is occasionally observed in wild type receptive virgins, usually early in courtship. We speculate that courtship

is initially aversive to the female which with continued courtship is adjusted to an opportunity to mate leading to reducing the speed and eventually accepting the male. While our work

highlights the impact of the acoustic stimuli produced by the male during courtship, it is well established that chemical stimuli such as cis-vaccenyl acetate (cVA) and cuticular

hydrocarbons are a major component of the communication between flies and play a role in the female’s decision to mate44,45,46. This work opens the way to investigate how chemical stimuli

contribute, in combination with courtship song, to the modulation of female speed during courtship. Wild type unreceptive flies, i.e., immature virgins and mated females, respond to

courtship differently from receptive virgins. Immature virgins do not slow down and pause less than mature virgins6,17,21. Mated females do not display high walking speed, as immature

females do, but show a positive correlation between the song amount and their speed6,18. In sum, some features of the natural unreceptive states are common to 70A09 silencing phenotype

indicating that 70A09 neurons may be differently active in receptive and unreceptive females. Beside a role in escape modulation, we have also uncovered a role of 70A09 neurons in

receptivity that is separable from the ability to escape. Though it is clear from wild type behaviour the close link between speed modulation during courtship and receptivity, which 70A09

neuron(s) are involved in the receptivity and the escape phenotype remains to be elucidated. A recent study characterised neurons in the central brain, pC2l, that are tuned to courtship song

and modulate the locomotor response in a sex-specific manner23. Though the exact identity of 70A09 neurons which are involved in the observed escape phenotypes is unknown, it is clear that

they do not overlap with _dsx_-positive pC2l since we have shown that the _dsx_ subset of 70A09 neurons do not show an escape phenotype. Moving forward it would be interesting to investigate

how pC2l and 70A09 neurons interact to produce a locomotor response to song. In conclusion, our work shed a light on the interactions between mating partners, by revealing a new role of the

male courtship song and identifying a set of brain neurons responsible for the song-induced female slowing down. The male song is a courtship cue with a dual role and opposite effects on

the female: it first induces escape, providing the female with enough time to assess the male, until the decision to mate is made, and then it prompts a decrease in locomotion, which in

turns will allow the male to get closer to the female and eventually copulate. The activity in 70A09 neurons is necessary for suppressing the song-induced escape by prompting a decrease in

locomotion and allowing to advance the courtship plot. Our findings highlight the complexity of male–female interactions during courtship, revealing a dual response of the female to

courtship song. METHODS FLY STOCKS Fly strains and sources are as follows: Canton-S (CS), w1118 47, GMR70A09-GAL4 and all lines in receptivity screen30, 65C12-DBD48, UAS-_Kir2.1_31,

Tub-GAL80TS32; _otd-nls_:FLPo36, UAS > STOP > _Kir2.1_34, UAS > STOP > _CD8-GFP_49, _8xLexAop2-FLP__L_50, Gad-LexA51, elavGAL4DBD52, ey-FLP53, _elav-_GAL8034, _Dilp3_-GAL454,

TH-DBD55 provided by Gerald Rubin, _UAS_ > _STOP_ > _csChrimson.mVenus_42 FLP-out version provided by Vivek Jayaraman, fruLexA56, fruGAL4 41 and dsxDBD57. CONSTRUCTION OF TRANSGENIC

LINES The _70A09_-LexA and _70A09_-AD DNA constructs were generated by Gateway cloning technology (Invitrogen). The entry clone (pCR8/GW/TOPO; Invitrogen) carrying _70A09_ enhancer

fragment58, generously provided by Gerald Rubin, was cloned into pBPLexA::p65Uw (Addgene plasmid #26230) and pBPp65ADZpUw (Addgene plasmid #26234). DNA constructs were verified by

restriction enzymatic digestion with _XbaI_ (New England Biolabs #R0145) for 2 h at 37 °C and purified using QIAGEN Plasmid Midi Kit (Cat Nº. 12,145), prior to injection into flies. Plasmid

was injected into y1 w67c23; P{CaryP}attP40 flies59 by adapting a protocol from Kiehart et al_._60. IMMUNOSTAINING AND MICROSCOPY Adult brains and VNCs were dissected in cold

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBL (PBS and 0.12 M Lysine) for 30 min at room-temperature (RT), washed three times for 5 min in PBT (PBS and 0.5%

Triton X-100) and blocked for 15 min at RT in 10% Normal Goat Serum (NGS, Sigma-Aldrich) in PBT. Tissues were incubated with the primary antibodies in blocking solution for 72 h at 4 °C. The

following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-GFP (1:2000, Molecular Probes, cat# A11122), and mouse anti-nc82 (1:10, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Samples were washed three

times for 5 min in PBT and incubated in Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (1:500, Invitrogen) for 72 h at 4 °C. The following secondary antibodies were used: anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to

Alexa 488 and anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa 594. Samples were washed three times for 5 min in PBT and mounted in VECTASHIELD (Vector Laboratories, Cat# H1000). Images were acquired on a

ZEISS LSM 710 confocal microscope using 20 × objective or 25 × Immersion objective (ZEISS). After acquisition, color levels were adjusted using Fiji61. BEHAVIOURAL EXPERIMENTS Fly

husbandry: Flies were raised in standard cornmeal-agar medium at 25ºC and 70% relative humidity in a 12 h:12 h dark:light cycle, unless otherwise indicated. For all experiments both female

and male flies were collected under CO2 anesthesia, soon after eclosion, and raised in regular food vials. Flies were raised in isolation for fertility and receptivity experiments. Females

were raised in groups of up to 25 per vial for looming experiments. For acute neuronal silencing experiments, female flies and males were raised at 18 °C from 6 to 14 days. Manipulated flies

were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h, whereas control flies were maintained at 18 °C. Both controls and manipulated flies, as well as males, were shifted to 25 °C 24 h before the behavioural

assay to prevent the effect of temperature treatment on the behaviour. For chronic neuronal silencing, female flies and males were raised at 25 °C from 4 to 8 days. Unless specified, the

flies used in behavioural experiments were 4–8 days old virgin females and males, and were tested in the same conditions as rearing (25 °C and 70% humidity). * 1. _Fertility screen_ To allow

mating, a male and a test female were paired in a food vial for 30 min after which the male was removed. One week later the vial was checked for progeny. For each line 20–25 females were

tested. The lines for which at least 25% of the females did not produce progeny were selected for further testing. In this initial large-scale screen, controls were not used. * 2. _Female

receptivity_ To test female receptivity, a single female was gently aspirated and transferred into circular acrylic chambers (small arenas: 16 mm in diameter × 4.5 mm height) and paired with

a male. Individual pairs were recorded for 30 min using Sony HDR-CX570E, HDR-SR10E, HDR-XR520VE or HDR-PJ620 video cameras (1440 × 1080 pixels; 25 frames per second). A white LED was used

as backlight source (Edmund Optics, cat# 83-875). * 3. _Receptivity with female tracking_ To allow the detailed analysis of the behaviour, a single female was gently aspirated and

transferred to a custom-made circular arena with a conical-shaped bottom that avoid flies walking on the walls62 (detailed arenas: 40 mm in diameter), allowing to track them as described in

Aranha et al_._16. Each female was allowed to habituate to the new environment for about 10 min and then paired with a male. Movies were acquired in dim light using an infrared 940 nm LED

strip (SOLAROX) mounted on an electric board developed by the Scientific Hardware Platform. Flies were recorded in grayscale (1024 × 1024 pixels, 60 frames per second), with a camera mounted

above the arena (Point Grey FL3-U3-32S2M-CS with a 5 mm fixed focal length lens (Edmund Optics)) with a HOYA 49 mm R72 infrared filter, for 20 min or until copulation occurred. Female flies

paired with _fruitless_ mutant males were recorded for 10 min. Bonsai63 was used for movie acquisition. To generate wingless males, individual CS male flies were anesthetized with CO2

approximately 15–20 h before the experiment. Wings were bilaterally cut at their base with microscissors or microforceps (WPI) under a scope. Flies were allowed to recover at 25ºC until the

experiment. * 4. _Receptivity in a restricted space_ To test receptivity in a restricted space, the small arenas were modified by inserting an acrylic adaptor, thus reducing the walking

surface (restricted arenas: 6 mm length × 5 mm width × 4.5 height). Single females were gently aspirated and transferred into the restricted arenas. Female flies were allowed to habituate to

the new environment for about 10 min before being paired with the male. Movies were acquired in dim light using an infrared 940 nm LED strip (SOLAROX) mounted on an electric board developed

by the Scientific Hardware Platform. Flies were recorded for 20 min in grayscale (1024 × 1024 pixels, 60 frames per second), with a camera mounted above the arena (Point Grey

FL3-U3-32S2M-CS with a 16 mm fixed focal length lens (Edmund Optics)) with a HOYA 49 mm R72 infrared filter. This setup allowed us to record two pairs of flies at the same time. Bonsai63 was

used for movie acquisition. * 5. _Looming experiment_ Behavioural apparatus and paradigm: Visual stimulation was delivered on a monitor (Asus ROG Strix XG258Q, 24.5") tilted at 45

degrees over the stage where the arenas were placed. This stage was backlit by an infrared (940 nm) LED array developed by the Scientific Hardware Platform. A 3 mm white opalino was placed

between the LED array and the arenas to ensure homogeneous illumination. We recorded behaviour at 60 Hz using a USB3 camera (FLIR Blackfly S, Mono, 1.3MP) with a 730 nm long pass filter (LEE

Filters, Polyester 87 Infrared). Behavioural arenas were 30 mm in diameter and 4 mm in height, and were built from opaque white and transparent acrylic sheets. Single flies were transferred

to each behavioural chamber using a mouth aspirator. After being transferred, flies were allowed to habituate to the new environment for a period of 2 min. The duration of this baseline

period was set based on the median duration that a male takes to start courting the female (latency to court). This baseline period was followed by a stimulation period that lasted 5 min,

and during which 7 looming stimuli were presented with an ISI that ranged between 10 and 20 s. Videos were acquired using Bonsai63 at 60 Hz and width 1104 × height 1040 resolution. Looming

stimulus: Looming stimuli were presented on the above-mentioned monitor running at 240 Hz refresh rate; stimuli were generated by a custom Bonsai workflow63. The looming effect was generated

by a black circle that increased in size over a white background. The visual angle of the expanding circle can be determined by the equation: θ(t) = 2tan − 1 (l / vt), where l is half of

the length of the object and v the speed of the object towards the fly. Virtual object length was 1 cm and speed 25 cm s − 1 (l / v value of 40 ms). Each looming presentation lasted for 500

ms. Object expanded during 450 ms until it reached a maximum size of 78° where it remained for 50 ms before disappearing. * 6. _Activation experiment_ For the activation experiment, the

female flies were individually collected and allowed to age in cornmeal-agar food containing 0.2 mM all trans-Retinal (Sigma-Aldrich, R2500) and reared in dim light until the experiment. The

same setup described in the Behavioural Experiment Sect. 3 was used. For the light stimulation a high-powered 610 nm LEDs arrays interspersed between the infrared LEDs on the blacklight

board was used. The arena was irradiated with a power in the 4–4.7 mV/cm2. A female and a male were gently aspirated and transferred in the arenas. They were allowed to habituate and only

when the male started courting the video recording was started. Videos were recorded for 9 min or until copulation. The activation protocol included a baseline that lasts 3 min, followed by

light stimulation during 3 min and a post-activation period of 3 min. DATA PROCESSING In order to quantify female receptivity, a custom-made software was developed to track the flies and

compute the time to copulation, when it occurred. To quantify flies’ behaviours, FlyTracker64 was used to track the two flies and output information concerning their position, velocity,

distance to the other fly, among others. A Courtship Classifier developed in the lab using the machine learning-based system JAABA65 was run to automatically identify courtship bouts.

Subsequently, in-house developed software PythonVideoAnnotator (https://biodata.pt/python_video_annotator) was used to visualize courtship events generated by JAABA and manually correct them

if necessary. Annotations were done from the beginning of courtship and during 10 min or until copulation. PythonVideoAnnotator was also used to manually annotate the copulation time,

considering the whole duration of the video. For the looming experiment, two main features were extracted from the videos using a custom-built Bonsai workflow: centroid position and pixel

change in a 72 × 72px ROI around the fly. QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Data analysis was performed using custom Python 3 scripts for all the experiments, except for the copulation

rate for small arenas receptivity experiments, for which GraphPad Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad Software) was used. All data, except those from flies excluded due to tracking errors, were

analysed. * 1. _Female receptivity and male behaviour parameters_ The latency to copulation was calculated from the beginning of male courtship. With exception of latency to copulation, all

quantifications were performed for the first 10 min of courtship or until copulation whichever happened first. Male courtship index was calculated as the ratio between courtship frames and

the total number of frames from the beginning of courtship to the end of the video. * 2. _Female locomotor parameters during male courtship_ For the characterisation of female locomotor

activity, mean speed, pausing and jumping were quantified. Since courtship is a prerequisite, we selected only videos with courtship index equal or above 20%. The three behaviours were

separately quantified in three different moments: (i) before courtship starts (# frames before courtship initiation, (ii) courtship ON (# frames of courtship since courtship initiation) and

(iii) courtship OFF (# frames of not courtship since courtship initiation). For the experiment with _fruitless_ mutant males, since courtship was absent, the three behaviours were quantified

when the distance between the two animals was below 5.5 mm, which is a proxy for courtship, and compared to the same behaviours when the distance was above 5.5 mm. The distance information

was extracted from the FlyTracker output (see Data processing section). Walking frames were defined as the frames in which female speed was within the range of 4–50 mm/s and the mean walking

speed for each fly was calculated by the sum of speed values divided by the number of walking frames. Pausing frames were defined as the frames in which the fly speed was below 4 mm/s, as

reported previously17. The pausing percentage was obtained normalizing the number of pausing frames over the total number of frames for each courtship moment. Jumps were defined as

instantaneous female speed above 70 mm/s. We set this value based on the discontinuity in the speed distribution and on the presence of peaks in the raw, un-binned speed data. Since a high

number of peaks were observed for speed values above 50 mm/s (upper limit for walking speed), manual observation of random peaks was performed. Below 70 mm/s most of the peaks corresponded

to fly transitions from the lid to the bottom of the arena and/or decamping. Therefore, we set the threshold for jumps at 70 mm/s. For the activation experiment, no speed filter was applied.

To observe females’ speed during the whole video recording, rolling average and standard error of the mean (SEM) applied to 15 s were calculated. * 3. _Female locomotor parameters during

looming stimulus_ Using the centroid position, a fly was considered to be walking if its speed was higher than 4 mm/s and lower than 75 mm/s. We identified jumping events by detecting peaks

in the raw data. A fly was classified as having jumped if its instantaneous speed exceeded a 75 mm/s, a threshold identified by a discontinuity in the speed distribution. The speed plots

represent all the moments in which the speed was below the jump threshold for those looming events in which the flies were walking in the 0.5 s bin preceding looming onset, and in the 0.5 s

bin from 2.0 to 2.5 s after loom offset. For statistical analysis of all experiments, Fisher’s exact test was performed to compare the copulation rate between two different groups. Prior to

statistical testing, Levene’s test was used to assess variance homogeneity and Shapiro–Wilk and D'Agostino-Pearson tests were used to assess normality across all individual experiments.

Independent groups were subjected to unpaired t-test (n = 2) or one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc pairwise Tukey’s test (n ≥ 3) if parametric assumptions were satisfied. If not,

Mann–Whitney U test (n = 2) or Kruskal–Wallis test followed by post hoc Dunn’s test (n ≥ 3) was used. For dependent groups, paired t-test (n = 2) or repeated measures ANOVA followed by post

hoc multiple pairwise paired t-test (n ≥ 3) were applied if parametric assumptions were satisfied. If not, Wilcoxon signed-rank test (n = 2) or Friedman’s test followed by post hoc Dunn’s

test (n ≥ 3) was used. Bonferroni correction to _p_ values was applied when multiple comparisons were performed. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare one data group with a dataset of

random values with median around zero and variance equivalent to the experimental group. The sample size for each condition is indicated in each plot. All the statistical details related to

main Figures and Supplementary Figures are included in Tables S2 and S3, respectively. The difference in sample size for the same condition in different analysis is due to the different

thresholds applied. REFERENCES * Tinbergen, N. _Social Behaviour of Animals_ (Champman and Hall, 1964). Google Scholar * Lenschow, C. & Lima, S. Q. In the mood for sex: Neural circuits

for reproduction. _Curr. Opin. Neurobiol._ 60, 155–168 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bastock, M. & Manning, A. The courtship of Drosophila melanogaster. _Behaviour_ 8,

85–111 (1955). Article Google Scholar * Fabre, C. C. G. _et al._ Substrate-borne vibratory communication during courtship in drosophila melanogaster. _Curr. Biol._ 22, 2180–2185 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hall, J. C. The mating of a fly. _Science_ 2, 1702–1714 (1994). Article ADS Google Scholar * Connolly, K. & Cook, R. Rejection

responses by female drosophila melanogaster: Their ontogeny, causality and effects upon the behaviour of the courting male. _Behaviour_ 44, 142–166 (1973). Article Google Scholar * Spieth,

H. T. Mating behavior in the genus Drosophila (Diptera). _Bull. AMNH_ 2, 61–106 (1952). Google Scholar * Tompkins, L., Gross, A. C., Hall, J. C., Gailey, D. A. & Siegel, R. W. The role

of female movement in the sexual behavior of Drosophila melanogaster. _Behav. Genet._ 12, 295–307 (1982). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Villella, A. & Hall, J. C. Chapter 3

neurogenetics of courtship and mating in drosophila. In _Advances in Genetics_ Vol. 62 67–184 (Elsevier, 2008). Google Scholar * Dukas, R. & Scott, A. Fruit fly courtship: The female

perspective. _Curr. Zool._ 61, 1008–1014 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Lasbleiz, C., Ferveur, J.-F. & Everaerts, C. Courtship behaviour of Drosophila

melanogaster revisited. _Anim. Behav._ 72, 1001–1012 (2006). Article Google Scholar * Mezzera, C. _et al._ Ovipositor extrusion promotes the transition from courtship to copulation and

signals female acceptance in drosophila melanogaster. _Curr. Biol._ 30, 3736-3748.e5 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wang, F., Wang, K., Forknall, N., Parekh, R. &

Dickson, B. J. Circuit and behavioral mechanisms of sexual rejection by drosophila females. _Curr. Biol._ 30, 3749-3760.e3 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ferveur, J.-F.

Drosophila female courtship and mating behaviors: Sensory signals, genes, neural structures and evolution. _Curr. Opin. Neurobiol._ 20, 764–769 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Wang, K. _et al._ Neural circuit mechanisms of sexual receptivity in Drosophila females. _Nature_ https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2972-7 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Aranha, M. M. _et al._ apterous brain neurons control receptivity to male courtship in drosophila melanogaster females. _Sci. Rep._ 7, 46242 (2017). Article ADS CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bussell, J. J., Yapici, N., Zhang, S. X., Dickson, B. J. & Vosshall, L. B. Abdominal-B neurons control drosophila virgin female receptivity. _Curr.

Biol._ 24, 1584–1595 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Coen, P. _et al._ Dynamic sensory cues shape song structure in Drosophila. _Nature_ 507, 233–237 (2014).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Crossley, S. A., Bennet-Clark, H. C. & Evert, H. T. Courtship song components affect male and female Drosophila differently. _Anim. Behav._

50, 827–839 (1995). Article Google Scholar * Ishimoto, H. & Kamikouchi, A. A feedforward circuit regulates action selection of pre-mating courtship behavior in female Drosophila.

_Curr. Biol._ 30, 396-407.e4 (2020). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * von Schilcher, F. The role of auditory stimuli in the courtship of Drosophila melanogaster. _Anim. Behav._ 24,

18–26 (1976). Article Google Scholar * Clemens, J. _et al._ Connecting neural codes with behavior in the auditory system of drosophila. _Neuron_ 87, 1332–1343 (2015). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Deutsch, D., Clemens, J., Thiberge, S. Y., Guan, G. & Murthy, M. Shared song detector neurons in drosophila male and female brains drive sex-specific

behaviors. _Curr. Biol._ 29, 3200-3215.e5 (2019). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Vaughan, A. G., Zhou, C., Manoli, D. S. & Baker, B. S. Neural pathways for the

detection and discrimination of conspecific song in _D. melanogaster_. _Curr. Biol._ 24, 1039–1049 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kamikouchi, A. _et al._ The neural basis of

Drosophila gravity-sensing and hearing. _Nature_ 458, 165–171 (2009). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yorozu, S. _et al._ Distinct sensory representations of wind and

near-field sound in the Drosophila brain. _Nature_ 458, 201–205 (2009). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhou, C. _et al._ Central neural circuitry mediating

courtship song perception in male Drosophila. _Elife_ 4, e08477 (2015). Article PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wang, F. _et al._ Neural circuitry linking mating and egg laying in

Drosophila females. _Nature_ 579, 101–105 (2020). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhou, C., Pan, Y., Robinett, C. C., Meissner, G. W. & Baker, B. S. Central

brain neurons expressing doublesex regulate female receptivity in Drosophila. _Neuron_ 83, 149–163 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Jenett, A. _et al._ A GAL4-driver line

resource for drosophila neurobiology. _Cell Rep._ 2, 991–1001 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Baines, R. A., Uhler, J. P., Thompson, A., Sweeney, S. T. &

Bate, M. Altered electrical properties in _Drosophila_ neurons developing without synaptic transmission. _J. Neurosci._ 21, 1523–1531 (2001). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * McGuire, S. E., Mao, Z. & Davis, R. L. Spatiotemporal gene expression targeting with the TARGET and gene-switch systems in Drosophila. _Sci. Signal._ 2004, l6 (2004). Article

Google Scholar * Häsemeyer, M., Yapici, N., Heberlein, U. & Dickson, B. J. Sensory neurons in the drosophila genital tract regulate female reproductive behavior. _Neuron_ 61, 511–518

(2009). Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar * Yang, C. _et al._ Control of the postmating behavioral switch in Drosophila females by internal sensory neurons. _Neuron_ 61, 519–526 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yapici, N., Kim, Y.-J., Ribeiro, C. & Dickson, B. J. A receptor that mediates the post-mating switch in Drosophila reproductive

behaviour. _Nature_ 451, 33–37 (2008). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Asahina, K. _et al._ Tachykinin-expressing neurons control male-specific aggressive arousal in Drosophila. _Cell_

156, 221–235 (2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Card, G. M. Escape behaviors in insects. _Curr. Opin. Neurobiol._ 22, 180–186 (2012). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Gibson, W. T. _et al._ Behavioral responses to a repetitive visual threat stimulus express a persistent state of defensive arousal in Drosophila. _Curr. Biol._ 25,

1401–1415 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * von Reyn, C. R. _et al._ A spike-timing mechanism for action selection. _Nat. Neurosci._ 17, 962–970 (2014). Article

CAS Google Scholar * Zacarias, R., Namiki, S., Card, G. M., Vasconcelos, M. L. & Moita, M. A. Speed dependent descending control of freezing behavior in Drosophila melanogaster.

_Nat. Commun._ 9, 3697 (2018). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Demir, E. & Dickson, B. J. Fruitless splicing specifies male courtship behavior in Drosophila.

_Cell_ 121, 785–794 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Klapoetke, N. C. _et al._ Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. _Nat. Methods_ 11, 338–346

(2014). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Pycraft, W. P. _The Courtship of Animals_ (Hutchinson&Co, 1914). Google Scholar * Kurtovic, A., Widmer, A. & Dickson,

B. J. A single class of olfactory neurons mediates behavioural responses to a Drosophila sex pheromone. _Nature_ 446, 542–546 (2007). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Grillet,

M., Dartevelle, L. & Ferveur, J.-F. A _Drosophila_ male pheromone affects female sexual receptivity. _Proc. R. Soc. B_ 273, 315–323 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Rybak,

F., Sureau, G. & Aubin, T. Functional coupling of acoustic and chemical signals in the courtship behaviour of the male _Drosophila melanogaster_. _Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B_ 269, 695–701

(2002). Article CAS Google Scholar * Morata, G. & Garcia-Bellido, A. Behaviour in aggregates of irradiated imaginal disk cells of Drosophila. _Wilhelm Roux’ Archiv für

Entwicklungsmechanik der Organismen_ 172, 187–195 (1973). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wu, M. _et al._ Visual projection neurons in the Drosophila lobula link feature detection to

distinct behavioral programs. _Elife_ 5, e21022 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hong, W. _et al._ Leucine-rich repeat transmembrane proteins instruct discrete

dendrite targeting in an olfactory map. _Nat. Neurosci._ 12, 1542–1550 (2009). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Pan, Y., Meissner, G. W. & Baker, B. S. Joint

control of Drosophila male courtship behavior by motion cues and activation of male-specific P1 neurons. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci._ 109, 10065–10070 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Diao, F. _et al._ Plug-and-play genetic access to drosophila cell types using exchangeable exon cassettes. _Cell Rep._ 10, 1410–1421 (2015). Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Luan, H., Peabody, N. C., Vinson, C. R. & White, B. H. Refined spatial manipulation of neuronal function by combinatorial restriction of transgene

expression. _Neuron_ 52, 425–436 (2006). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Therrien, M., Wong, A. M. & Rubin, G. M. CNK, a RAF-binding multidomain protein required

for RAS signaling. _Cell_ 95, 343–353 (1998). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Buch, S., Melcher, C., Bauer, M., Katzenberger, J. & Pankratz, M. J. Opposing effects of dietary

protein and sugar regulate a transcriptional target of Drosophila insulin-like peptide signaling. _Cell Metab._ 7, 321–332 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Aso, Y. _et al._

The neuronal architecture of the mushroom body provides a logic for associative learning. _Elife_ 3, e04577 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mellert, D. J., Knapp,

J.-M., Manoli, D. S., Meissner, G. W. & Baker, B. S. Midline crossing by gustatory receptor neuron axons is regulated by _fruitless, doublesex_ and the Roundabout receptors.

_Development_ 137, 323–332 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Pavlou, H. J. _et al._ Neural circuitry coordinating male copulation. _Elife_ 5, e20713 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Pfeiffer, B. D. _et al._ Tools for neuroanatomy and neurogenetics in Drosophila. _Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci._ 105, 9715–9720 (2008).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Markstein, M., Pitsouli, C., Villalta, C., Celniker, S. E. & Perrimon, N. Exploiting position effects and the gypsy

retrovirus insulator to engineer precisely expressed transgenes. _Nat. Genet._ 40, 476–483 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kiehart, D. P., Crawford, J. M.

& Montague, R. A. Collection, dechorionation, and preparation of Drosophila embryos for quantitative microinjection. _CSH Protoc._ 2007, 4717 (2007). Google Scholar * Schindelin, J. _et

al._ Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. _Nat. Methods_ 9, 676–682 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Simon, J. C. & Dickinson, M. H. A new chamber

for studying the behavior of drosophila. _PLoS ONE_ 5, e8793 (2010). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Lopes, G. _et al._ Bonsai: An event-based framework for

processing and controlling data streams. _Front. Neuroinform._ 9, 2 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Eyjolfsdottir, E. _et al._ Detecting Social Actions of Fruit Flies. in _Computer Vision

– ECCV 2014_ (eds. Fleet, D., Pajdla, T., Schiele, B. & Tuytelaars, T.) 772–787 (Springer International Publishing, 2014). * Kabra, M., Robie, A. A., Rivera-Alba, M., Branson, S. &

Branson, K. JAABA: Interactive machine learning for automatic annotation of animal behavior. _Nat. Methods_ 10, 64–67 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Susana Lima and members of the Vasconcelos laboratory for feedback on the manuscript, Anita Sousa for help with the fertility screen, Miguel Gaspar for help with

the python scripts, the Scientific Hardware platform for help with building the arenas and setups, the Scientific Software platform for developing the python video annotator, the molecular

and transgenic tools and glass wash and media preparation platforms for support with cloning, the fly facility and the imaging platform-ABBE. Figures 1a and 2a were drawn by Cecilia Mezzera

and originally published in Aranha et al.16 under a CC BY 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Figure 3a was drawn by Ricardo Zacarias and originally published in

Zacarias et al_._40 under a CC BY 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). We also thank Gerald Rubin and Vivek Jayaraman for sharing reagents. This work was supported by

Fundação Champalimaud, Portuguese national funds, through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia—in the context of the projects UIDB/04443/2020, PTDC/MED-NEU/30105/2017, Congento,

LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-02270, PPBI—LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-022122 and BioData.pt—LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-022231. E.A. was supported by FCT doctoral fellowship under the Graduate Program Science for

Development (SFRH/BD/113753/2015). M.M.A. was supported by a FCT postdoctoral fellowship (SFRH/BDP/777362/2011). M.A.M. is supported by H2020-ERC-2018-CoG819630-A-Fro. AUTHOR INFORMATION

AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Champalimaud Research, Champalimaud Center for the Unknown, 1400-038, Lisbon, Portugal Eliane Arez, Cecilia Mezzera, Ricardo M. Neto-Silva, Sophie Dias, Marta A.

Moita & Maria Luísa Vasconcelos * Trinity College Institute of Neuroscience, School of Genetics and Microbiology, Smurfit Institute of Genetics and School of Natural Sciences, Trinity

College Dublin, Dublin-2, Ireland Márcia M. Aranha Authors * Eliane Arez View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Cecilia Mezzera View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ricardo M. Neto-Silva View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Márcia

M. Aranha View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sophie Dias View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Marta A. Moita View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Maria Luísa Vasconcelos View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS E.A. and M.L.V. conceived and designed the project. M.M.A. together with S.D. performed the initial fertility and receptivity screen. R.M.N.S.

and M.A.M. designed and performed the looming experiments. All other experiments were performed and analysed by E.A. with the participation of C.M. in the activation, fruitless and wingless

experiments. M.L.V. provided guidance and wrote the manuscript with E.A., C.M. and R.M.N.S. All authors reviewed the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Maria Luísa

Vasconcelos. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION Supplementary Video 1. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This

article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as

you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party

material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the

copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Arez, E., Mezzera, C.,

Neto-Silva, R.M. _et al._ Male courtship song drives escape responses that are suppressed for successful mating. _Sci Rep_ 11, 9227 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88691-w

Download citation * Received: 08 December 2020 * Accepted: 12 April 2021 * Published: 29 April 2021 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88691-w SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative