- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT The question of whether the iconic avialan _Archaeopteryx_ was capable of active flapping flight or only passive gliding is still unresolved. This study contributes to this debate

by reporting on two key aspects of this fossil that are visible under ultraviolet (UV) light. In contrast to previous studies, we show that most of the vertebral column of the Berlin

_Archaeopteryx_ possesses intraosseous pneumaticity, and that pneumatic structures also extend beyond the anterior thoracic vertebrae in other specimens of _Archaeopteryx_. With a minimum

Pneumaticity Index (PI) of 0.39, _Archaeopteryx_ had a much more lightweight skeleton than has been previously reported, comprising an air sac-driven respiratory system with the potential

for a bird-like, high-performance metabolism. The neural spines of the 16th to 22nd presacral vertebrae in the Berlin _Archaeopteryx_ are bridged by interspinal ossifications, and form a

rigid notarium-like structure similar to the condition seen in modern birds. This reinforced vertebral column, combined with the extensive development of air sacs, suggests that

_Archaeopteryx_ was capable of flapping its wings for cursorial and/or aerial locomotion. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS POWERED FLIGHT IN HATCHLING PTEROSAURS: EVIDENCE FROM WING

FORM AND BONE STRENGTH Article Open access 22 July 2021 A NEW CONFUCIUSORNITHID BIRD WITH A SECONDARY EPIPHYSEAL OSSIFICATION REVEALS PHYLOGENETIC CHANGES IN CONFUCIUSORNITHID FLIGHT MODE

Article Open access 21 December 2022 _ARCHAEOPTERYX_ FEATHER SHEATHS REVEAL SEQUENTIAL CENTER-OUT FLIGHT-RELATED MOLTING STRATEGY Article Open access 08 December 2020 INTRODUCTION Living

birds have extensively pneumatized postcrania, due to their unique and extremely efficient respiratory system1,2. This adaptation includes a series of pneumatic diverticula that derive from

large air sacs, encompass the lungs, and invade different parts of the skeleton3, leaving clear marks (pneumatic foramina) found in both avian and non-avian dinosaurs4,5,6. Reconstructions

of pneumatic structures in fossil archosaurs have been previously based on comparisons with extant birds1,2,5,6,7,8. Evidence used to infer intraosseous pneumaticity for dinosaurs, in

particular isolated foramina in compact bone or “blind” fossae, remains ambiguous however, as these cavities can house other structures such as muscles, fat, or neurovascular tissue1. The

only unambiguous, reliable indicators of intraosseous pneumaticity are cortical foramina and communicating fossae connected with larger cavities within the bone1. Furthermore, the locations

of foramina in the vertebrae or limb bones of dinosaurs that are comparable to those in extant birds support the interpretation of such structures as pneumatic1,2,7. The large cavities

within pneumatic vertebrae of dinosaurs have been descriptively separated according to their architecture into larger and rounded camerae, and smaller and more angular-walled camellae8,9,10.

Both types of internal pneumatic structures can occur in the same skeletal element, and multiple camellae can create a specific honeycomb-like pattern as in extant birds, described as

somphospondylous10. The anteroposterior extension and spatial distribution of intraosseous pneumaticity provides critical anatomical evidence enabling reconstructions of the respiratory

apparatus. The extent of pneumaticity also enables assessment of body weight, locomotor preferences, and metabolic activity, and therefore provides insights on the paleobiology and behavior

of extinct animals5,6,7. In _Archaeopteryx_, both the presence and extent of intraosseous pneumaticity has been controversially discussed ever since the 19th century11. A recent

microtomographic study on the Daiting specimen (_Archaeopteryx albersdoerferi_) showed that all cranial bones, shoulder girdles, and wing bones contain internal pneumatic cavities12. Similar

observations have been based on the Berlin, London, and Eichstätt specimens, which preserve foramina on the surfaces of their presacral vertebrae and pubes1,7,13,14,15. Pneumatic foramina

have been described in the 2nd to 5th cervical vertebrae1,7,13,15 and posterior presacral vertebrae of the Berlin _Archaeopteryx_16,17; this specimen is also known to have hollow thoracic

ribs13. The most unequivocal pneumatic structure seen in the postcranial skeleton of the Berlin specimen is the pneumatic foramen in the body of the 5th cervical vertebra1, exemplifying the

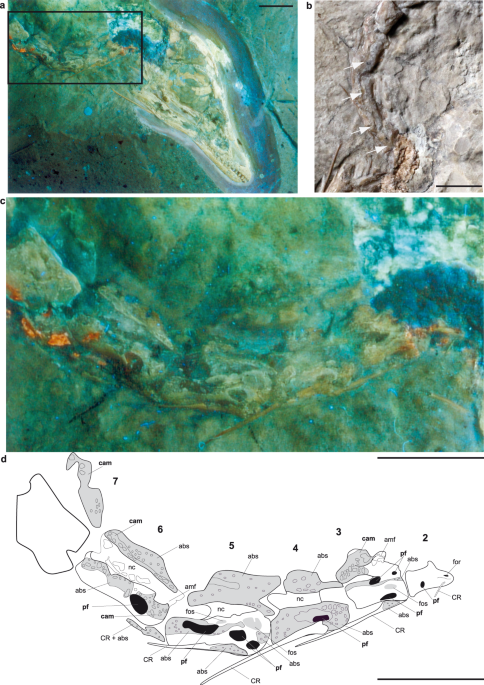

‘common pattern’ seen in earlier-diverging theropod dinosaurs7. Here, we describe intact and incomplete postcranial bone surfaces in the Berlin _Archaeopteryx_ (MB.Av.101; MB = Museum

Berlin, Av = Collection of fossil birds), utilizing long-wave UV light15,18 to reveal pneumatic structures that are hidden, or difficult to discern, under visible light conditions (Fig. 1).

Previous work has shown that UV light is far more sensitive than visible light to the increased contrast between fossilized bone, rocky infill, and surrounding matrix15,18,19,20,21. A

previous description based on UV observations of the Berlin _Archaeopteryx_ (MB.Av.101)15 has corroborated other reports1,13 regarding the presence of pneumatic foramina in the cervical

vertebral column and hollow vertebral bodies for the 7th to 10th presacral vertebrae. The new UV findings we present here extend these results, enable a detailed account of all unambiguous

pneumatic structures in the postcranial skeleton of MB.Av.101, and confirm that numerous postcranial bones of _Archaeopteryx_ were reduced in mass via hollow interiors (Table S1). RESULTS In

the Berlin _Archaeopteryx_, the vertebral cortex has been abraded in most presacral vertebrae, possibly due to repeated preparation15,18, exposing the internal bone structure of the

vertebrae and ribs. UV light conditions expose pneumatic structures more clearly than under visible light, and reveal a far more extensive distribution of intraosseous pneumaticity than has

been described since the 19th century. Sharp-lipped pneumatic foramina, which are distinguished from nutrient foramina by their larger diameter13, are present at the vertebral body and

neural arch of the 2nd to 5th cervical vertebrae, as reported before1,13,15. Pneumatic foramina can also be identified on the 6th, 16th, and 22nd presacral vertebrae (Figs 1 and 2, Table

S1). In the 19th presacral vertebra, a combination of a fossa with a communicating foramen is visible at the vertebral body (Fig. 2d). In contrast, small foramina visible in most of the

vertebrae likely represent nutrient foramina, and are therefore not evidence for intraosseous pneumaticity1,13. In the 8th to 14th presacral vertebrae (Fig. 2), and the 1st to 3rd, 12th, and

14th to 16th caudal vertebrae (Fig. 3), the interiors exhibit large internal pneumatic chambers, or camerae. The 3rd, 8th to 14th, 16th, and 20th presacral vertebrae, and the 2nd, 5th, 6th

and 11th caudal vertebrae expose pneumatic camellae. These camellae are small, sometimes rounded but mostly angular voids, separated from each other by thin bone walls (Figs 1 and 2b,c);

they form a characteristic honeycomb-like pattern that can also be observed in the pneumatic vertebrae of extant birds1. In most vertebrae, the camellae are combined with unambiguous

pneumatic foramina and large internal camerae (Table S1) typical for pneumatized bones, and are more often preserved in the neural arches than in the vertebral bodies. At the vertebral

bodies, the abraded cortical bone exposes an internal structure that consists of regular, small, and mostly oval pores that are only half as large as the camellae (abs). Rounded and

irregularly distributed voids the same size as camellae are visible (amf) in other areas, mostly along the neural arches and in particular all presacral vertebrae and the 3rd and 6th to 8th

caudal vertebra (Fig. 1–3). These structures cannot be unambiguously identified as pneumatic structures, as they do not correspond to a typical camellate pattern as described above, but

might instead represent areas of spongy bone. The presence of spongy internal bone structure can be taken as evidence for lightweight vertebrae in MB.Av.101. The thoracic ribs also exhibit a

pattern comprising small regular and irregular voids in their heads and along their shafts, while their internal shafts are hollow13 (Fig. 2a,d; Table S1). A pattern of small and irregular

pores can be observed in the posterior process and ventral margin of the ilium, and the head of the pubis (Fig. 3). Only small putative nutrient foramina are observed within the humerus,

pelvic bones, femur, and tibia (Figs 2a,d and 3a, Table S1), so unambiguous evidence for intraosseous pneumaticity in the appendicular skeleton is still unknown1,8. The overall skeletal

pneumaticity in _Archaeopteryx_ was calculated using the Pneumaticity Index (PI), as it provides a quantitative measure for the standardized comparison of postcranial pneumaticity among

multiple avian species, independent of phylogeny, body size, and behavior22. Mapping of intraosseous pneumaticity in the Berlin _Archaeopteryx_ yielded a PI of at minimum 0.39 (7 of 18

anatomical units being pneumatic). This value is comparable to the PI of a few of the extant anseriform birds previously reported, such as _Mergus merganser_ and _Anas georgica_22 (both

0.41). Our UV light observations also corroborate the presence of a notarium-like structure of fused presacral vertebrae in the Berlin _Archaeopteryx_. Fused anterior thoracic vertebrae have

been mentioned briefly before23, but never described in detail. Our images reveal the presence of a massive, rod-shaped ossification above the apex of the 16th presacral neural spine and

connecting to the anterior spine of the 17th (Fig. 4a,b). The caudodorsal corner of the 17th neural spine and the craniodorsal corner of its 18th counterpart comprise a long, thin, rod-like

structure that bridges and tightly binds the neural spines together (Fig. 4a,b). The neural spines of the 19th to 20th presacral vertebrae are equally drawn out in their anterodorsal and

posterodorsal corners, and fused dorsally with their adjacent neural spines. However, the connection between these elements is partly broken (Fig. 4a,b), while the neural spine of the 21st

presacral vertebra has extended anterodorsal and posterodorsal corners. DISCUSSION It is generally accepted that the clearest marker of skeletal pneumaticity is the presence of intraosseous

pneumatic structures correlated with foramina1,7,24. Hitherto, the presacral distribution of pneumatic structures in _Archaeopteryx_ has been discussed solely on the basis of described

pneumatic foramina, which is considered controversial1,7. Previous workers have noted the existence of such pneumatic foramina on the surfaces of the cervical and thoracic vertebrae,

humerus, and pubis of the Berlin, London, Eichstätt, and Thermopolis specimens of _Archaeopteryx_1,7,8,12,13,14,15,16,17,25 (Table S2). However, the most recent integrative study concluded

that just the cervical and anteriormost thoracic vertebrae were pneumatized in _Archaeopteryx_, analogous with the plesiomorphic ‘common pattern’ seen in basal theropod dinosaurs7. In this

study, we expand our knowledge of the Berlin _Archaeopteryx_ with the first evidence of unambiguous intraosseous pneumatic structures (i.e., internal cavities such as camerae and camellae).

The UV findings now enable convincing identification of internally pneumatic presacral vertebrae (2nd to 14th, 16th, 20th, 22nd) and caudal vertebrae (1st to 3rd, 5th, 6th, 11th, 12th, 14th

to 16th), demonstrating the extension of pneumatic foramina and intraosseous pneumatic structures to most the vertebral column. Unambiguous traces of vertebral pneumaticity are absent in the

remaining thoracic vertebrae, which is consistent with other specimens of _Archaeopteryx_1,7,13,14,26. The thoracic ribs are hollow, which has also been reported for the12th specimen of

_Archaeopteryx_26. The presence of intraosseous pneumaticity in the remaining caudal vertebrae remains unclear, due to the lack of a combination of unambiguous pneumatic structures. We found

evidence for at least a spongy and therefore light bone architecture in the 1st and 2nd sacral vertebra, the ilium and the pubis, as well as in some other caudal vertebrae (Fig. 3). Our

survey revealed furthermore that the abraded and broken lumbar vertebra of the Maxberg specimen27 also includes a pneumatized internal vertebral body including camellae (Table S2).

Additionally, X-ray images of the thoracic vertebrae of the Maxberg _Archaeopteryx_27 and the cervicals of the Thermopolis specimen25 corroborate the presence of camellae within these

vertebrae (Table S2). Additionally, camellate intraosseous pneumatic structures in the last two cervical vertebrae, as well as a pneumatic foramen in the 1st thoracic vertebra (Rauhut _et

al_. 2018, p.30; Fig. 17), have been described for the most recently reported 12th specimen of _Archaeopteryx_26. Therefore, the presence of intraosseous postcranial pneumaticity in at least

four specimens of _Archaeopteryx_ including the Berlin, Maxberg, Thermopolis, and the 12th specimen, is documented (Table S2). At least in two specimens, the Maxberg and the Berlin

_Archaeopteryx_, pneumatic structures extend outside the region of the anterior thoracic vertebrae. A hollow caudal vertebra is described for the 12th _Archaeopteryx_26, although it is

unclear whether this represents intraosseous pneumaticity. Clearly seen in the Berlin _Archaeopteryx_, the pattern of intraosseous pneumaticity comprises a combination of closely-spaced

honeycomb-shaped camellae bounded by thin bone walls (Fig. 2b), essentially similar to that of extant birds1,6,8,10. Camellate pneumatic bone is also found in a range of non-avialan

dinosaurs (e.g. _Aerosteon_28, _Tyrannosaurus_29, and other neotheropods8) and in the avialan _Rahonavis_30, whereas large internal pneumatic camerae have been less frequently reported

(e.g., in megalosauroids31, dromaeosaurids8 and ornithomimosaurs32). Our new data demonstrate that the pneumaticity status of _Archaeopteryx_ does not, in fact, conform to the plesiomorphic

“common pattern” of non-avialan theropod dinosaurs7. Instead, _Archaeopteryx_ possesses what can be termed “extended pattern of pneumaticity” (EPP)7, which includes the posterior thoracic

vertebrae, and at least some anterior caudal vertebrae. The EPP is also seen in basal Neotheropoda6,7, as well as in most neotheropod clades, including Tyrannosauroidea28,

Oviraptorosauria33,34,35, Dromaeosauridae36, and Troodontidae37,38, where it is thought to have evolved independently7. Among Maniraptora, only Oviraptorosauria possesses a stronger

pneumatized vertebral column, including the complete tail39. Apart from _Archaeopteryx_, evidence of postcranial pneumaticity within Avialae is patchy, possibly related to the small body

size and fragmentary preservation of most specimens. Pneumatic foramina are documented for the cervical vertebrae of confuciusornithid birds40, and for the cervical and anterior thoracic

vertebrae of _Rahonavis_ and some enantiornithid birds30, which would conform to a “common pattern” of intraosseous pneumaticity. One report of a pneumatic foramen in the humerus of an

enantiornithid bird41 might indicate an EPP, but the evolutionary development of this pattern within Avialae still remains unclear. In any case, the level of pneumaticity we found in

_Archaeopteryx_ already corresponds with the EPP seen in some extant neornithine birds, including non-diving anseriforms22. The new evidence of intraosseous pneumatization in _Archaeopteryx_

presented here indicates that the respiratory system of this avialan included an air sac distribution similar to that of living birds1,3,6,22 (Table S1). The extensive intraosseous

postcranial pneumatic structures provide unambiguous evidence for the presence of cervical air sacs that pneumatize cervical vertebrae and ribs, as well as anterior to mid-thoracic vertebrae

and thoracic ribs. Intraosseous pneumatization of the mid- to posterior thoracic and caudal vertebrae provide unambiguous evidence for the existence of abdominal air sacs1,3,22 (Fig. 5).

There is no osteological evidence for the presence of clavicular and anterior thoracic air sacs surrounding the lungs, which would pneumatize the humerus22 (Fig. 2, Table S1). The exact

position of the lungs also cannot be reconstructed, because this organ is not associated with osteological traces; the lack of pulmonary foramina in thoracic vertebrae of _Archaeopteryx_

makes it unlikely that lung tissue pneumatized these vertebrae on a large scale1. Similarly, the presence of posterior thoracic air sacs, present in extant birds, cannot be reconstructed for

_Archaeopteryx_ because these air sacs do not pneumatize the skeleton1,3,22. The reconstruction of air sacs in _Archaeopteryx_ (Fig. 5) confirms the already assumed1,7 presence of a

bird-like, high-compliance lung-air sac respiration system, incorporating lungs fixed at the rigid thoracic vertebral column and ventilated by air sacs positioned anteriorly and posteriorly

to it. The rostrad extension of skeletal pneumatization in theropod dinosaurs is a “centrum-first” pattern7, which means that first the vertebral bodies are pneumatized via pneumatic

foramina (“intramural pneumatization”)42, followed by the neural arches. This is consistent with the occurrence of pneumatic foramina throughout the cervical vertebral column of the Berlin

specimen (Fig. 1). In the posterior direction, pneumatization proceeds in a “neural arch-first” pattern, with the neural arches being pneumatized first, followed by pneumatization of the

vertebral bodies1,7. Pneumatic diverticula can proceed through the medullary region first, and enter the vertebral body internally, as in extant birds1,10,43. This pattern likely explains

the lack of pneumatic foramina observed in the thoracic vertebral bodies in _Archaeopteryx_ (Fig. 2), which contrasts its rich intraosseous pneumatic structures. Such an absence of pneumatic

foramina in the mid- thoracic region is consistent with many extant birds, in which pneumatic foramina are reduced in the thoracic vertebral series towards the sacrum1. Pneumatization of

the postcranial skeleton has a direct weight-reducing effect, by replacing bone and marrow with air-filled cavities42,44,45. A correlation between the degree of vertebral pneumaticity and

body size was found in large-bodied, non-avian theropod dinosaurs7. In extant birds, the degree of postcranial pneumaticity has traditionally been linked to body mass and diving behavior,

with the assumption that larger-bodied birds are more pneumatic than smaller-bodied birds, and the known absence of intraosseous pneumaticity in diving birds such as penguins22. At least

within anseriform birds, no statistically significant relationships between body size and Pneumaticity Index has been found22, so that reduced or absent intraosseous pneumaticity (such as in

diving taxa) seems not to be generally correlated with the absence of active flight. In smaller extant birds, the threshold of a critical body mass related to the energetic requirements of

flight is not reached by a reduction or increase of intraosseous pneumaticity, meaning that the amount, presence, or absence of postcranial intraosseous pneumaticity gives no information on

the flight capability of an extant bird22. However, if the metabolic activity of a fossil avialan such as _Archaeopteryx_ was different than that of extant birds, then the increase of

intraosseous pneumaticity might very well have had an effect on the critical body mass, and thereby also the flight capability in _Archaeopteryx_. Nevertheless, given the remaining

uncertainty in the reconstruction of both the total extension of postcranial intraosseous pneumaticity and the presence of all pulmonary air-sacs, the precise estimation of body mass in

_Archaeopteryx_ remains speculative. A hypothetical adult (somatically mature) _Archaeopteryx_ has been reconstructed to exceed 500 mm in body length and have a body mass between 0.8 and 1

kg, comparable to a raven (_Corvus corax_)46, values which we assume to be within the possible ranges for this taxon and not contradicted by the new data on intraosseous pneumaticity in this

study. The documentation of stiffening structures in neural spines of the thoracic vertebral column of _Archaeopteryx_ is rather novel, and we argue that these ossifications represent the

earliest known occurrence of a notarium-like structure on the line to extant birds, pushing back its origin to Paraves. Previously, spinal processes in the thoracic vertebrae had only been

described in late Cretaceous enantiornithine birds41. It is also interesting to note the absence of stabilization structures in basal birds more derived than _Archaeopteryx_, such as the

Confuciusornithidae, as well as the heterogeneous distribution of notaria in extant birds47,48,49,50,51. The apparent absence of these structures in other specimens of _Archaeopteryx_ must

remain speculative, and might be due to differing degrees of tendon ossification and/or preservation in these specimens. In several members of extant avian groups such as Tinamiformes,

Podicipediformes, Phoenicopteriformes, Galliformes, Columbiformes, Pelecaniformes, Falconiformes, Gruiformes, and Caprimulgiformes, the vertebrae of the thorax form a notarium; this is a

rigid structure created by 2–5 ankylosed vertebrae, including ossified tendons and ligaments, and separated in most cases from the synsacrum by at least one “free” or unankylosed

vertebra47,48,49,50,51. Importantly, the fusion of neural spines in _Archaeopteryx_ lies in the thoracic vertebral column between the 16th and the 22nd presacral vertebrae (Fig. 4a,b),

corresponding to the notarium region in extant avians51, and there is also a vertebral gap between the fused and sacral regions. The narrow, ‘rod-like structures along the neural spines are

interpreted to represent ossified ligaments52 or tendons of the epaxial trunk musculature. These would have acted as bony splints52, and likely contributed to an incipient ankylosis between

the vertebrae (although the vertebral bodies themselves are not fused with each other). A relatively rigid thoracic vertebral column is required for a bird-like respiration mechanism3, and

is therefore an important structure to be documented in _Archaeopteryx_. In extant birds, the biological importance of the notarium is explained mostly as a rigid stabilization structure,

counteracting mechanical stress occurring during wing-driven flapping flight and acting as a shock absorber during landing50. A notarium has also been described for some pterosaurs as an

adaptation to active flight53,54. In any case, fusion of the neural spines creates a more stable (but less flexible) region in the vertebral column, which acts as a unit and can be more

effectively stabilized by the available muscles and ligaments against the mechanical forces during locomotion. Ultimately, reinforcement structures in the thoracic vertebral column can be

interpreted to facilitate novel locomotor modes, in particular the development of active flapping flight or bipedal running supported by flapping wings, that increases stresses acting on the

vertebral column. There has been controversial anatomical evidence on the ability of _Archaeopteryx_ for gliding or flapping flight27,55,56,57,58,59. Nevertheless, the reinforcement

structures observed in the trunk is indirect evidence for the increased use of forelimbs in _Archaeopteryx_, and depicts a stabilization trend that continues on the line to extant birds with

the reduction in the number and increasing intervertebral fusion of thoracic vertebrae into a regional notarium47,48,52. CONCLUSIONS We demonstrate that _Archaeopteryx_ possessed a derived,

bird-like postcranial pneumatization pattern that comprises intraosseous pneumatic camellae and camerae within the presacral vertebral column and caudal vertebrae. The new observations

furthermore confirm that expanded postcranial pneumatic structures and a bird-like respiratory system, both important physiological adaptations for powered flight, were present in

_Archaeopteryx_. Whereas the number of pneumatic bones has a direct effect on weight reduction in large-bodied dinosaurs5,7, the camerate and camellate architecture of pneumatized bone is

more likely determined by mechanical factors in the vertebral column, in concert with the evolutionary development and phylogenetic integration of the taxa. In _Archaeopteryx_, the direct

effect on weight-reduction of the vertebral column by intraosseous pneumatic structures was moderate. As an indirect effect, the lightened pneumatic vertebral column would have needed less

muscle forces to be stabilized against the mechanical loads that occur during all locomotor modes. Intraosseous pneumatization in _Archaeopteryx_ was important for the metabolism of the

animal, because the pneumatic epithelium replaces metabolically costly and massive bone, which reduces metabolic energy consumption and locomotion costs, and helped to increase the metabolic

performance of the animal7,45,59,60. The putative high energetic advantage of a pneumatic postcranium7,24 demonstrates the particular importance for a correct establishment of the

pneumaticity status in _Archaeopteryx_. The presence of an expanded pneumatization pattern in _Archaeopteryx_ indicates facilitation of an active lifestyle7,12 and allows characterizing

_Archaeopteryx_ as a taxon that already had the metabolic prerequisites for this highly demanding active lifestyle and an avian-like, high-performance endothermy. The presence of a

notarium-like stabilizing structure in the vertebral column in _Archaeopteryx_ is fully in line with the new evidence on its expanded pneumaticity pattern, and adds another piece of evidence

for the potential of this taxon for active, wing-driven flapping flight. METHODS The main slab of the Berlin specimen of _Archaeopteryx_, MB.Av.101, was observed directly (by the naked eye)

and with microscopy. The images taken by Helmut Tischlinger with the help of longwave UV light (365–366 nm) in combination with selective filter techniques15,21 were examined carefully and

compared to the original specimen. The UV photographs are available at the MfN. Additionally, new photographs under longwave UV radiation were taken by M.K. to supplement the older images

and compare both of them. Comparative photographs under visible light were provided by R.C. A survey of other described specimens of _Archaeopteryx_ has been done mainly by literature to get

an idea of potentially preserved pneumatic structures. The Maxberg specimen of _Archaeopteryx_ is lost and therefore could only be examined by photographs from Wellnhofer27. Data on the

Thermopolis specimen of _Archaeopteryx_ were taken from Mayr _et al_.25. We assume that the first preserved vertebra visible in the head region represents the 2nd cervical because of its

integration with the occiput; thus, the first vertebra with a thoracic rib is the 11th presacral vertebra (which has its rib slightly caudoventrally emplaced beneath the scapula), and so the

first sacral vertebra (the rostralmost vertebra without a thoracic rib) is medial to the anterior iliac blade. We count therefore 22 presacral vertebrae in this specimen (i.e., 10

cervicals, and 12 rib-bearing thoracic vertebrae), one less than in the other known specimens of _Archaeopteryx_14,27. We calculated a Pneumaticity Index22 (PI) as a quantitative measure to

compare the amount of pneumatic elements throughout the postcranial skeleton with some extant birds. The PI is defined as the ratio between the number of pneumatic postcranial elements and

the total number of postcranial elements22. Postcranial elements are subdivided into anatomical units (AU), yielding the equation of PI = #AU pneumatic/#AU total. The following AUs (see also

Table S3) were defined for _Archaeopteryx:_ Composite units = ANC, Anterior Cervical Vertebrae (1st to 3th cervical); MC, Middle Cervical Vertebrae (4th to 6th cervical); POC, Posterior

Cervical Vertebrae (7th to 10th cervical); ANT, Anterior Thoracic Vertebra (1st to 6th thoracic); POT, Posterior Thoracic Vertebrae (7th to 12th thoracic); SS, Synsacral Vertebrae; CAA,

Anterior Caudal Vertebrae; CAP, Posterior Caudal Vertebrae; TR, Thoracic Ribs; CAR, Caudal Ribs and Chevrons; PE, Pelvis (Ilium, Ischium, Pubis); DFL, distal forelimb elements (i.e., bones

distal to elbow joints); DHL, distal hind limb elements (i.e., bones distal to knee joints); Individually scored units = CC, coracoids; FU, furculae; FM, femora; HU, humeri; SC, scapulae. In

the Berlin specimen of _Archaeopteryx_, 7 (ANC, MC, POC, ANT, POT, CAA, TR) of the listed 18 AUs are unambiguously pneumatic, yielding a minimum PI OF 7:18 = 0.39. DATA AVAILABILITY The

original Berlin specimen of _Archaeopteryx_, MB.Av.101, is housed in the collection of fossil vertebrates at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin (MfN) and can be studied upon request at the

institution. The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. REFERENCES * O’Connor, M. P.

Postcranial pneumaticity: An evaluation of soft-tissue influences on the postcranial skeleton and the reconstruction of pulmonary anatomy in archosaurs. _J. Morphol._ 267, 1199 (2006).

Article Google Scholar * O’Connor, M. P. The postcranial axial skeleton of _Majungasaurus crenatissimus_ (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. _Soc. Vertebr.

Paleontol. Mem._ 8(27), 127 (2007). Google Scholar * Duncker, H.-R. The lung air sac system of birds. _Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cel._ 45, 1 (1971). Google Scholar * Perry, S. F. Method for

reconstructing the respiratory system of extinct animals. _Sauropod dinosaurs as a case in point. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A_ 143, 61 (2006). Google Scholar * Wedel, M. J. Vertebral

pneumaticity, air sacs, and the physiology of sauropod dinosaurs. _Paleobiology_ 29, 243 (2003). Article Google Scholar * O’Connor, M. P. & Claessens, L. P. A. M. Basic avian pulmonary

design and flow-through ventilation in nonavian theropod dinosaurs. _Nature_ 436, 253 (2005). Article ADS Google Scholar * Benson, R. B. J., Butler, R. J., Carrano, M. T. & O’Connor,

M. P. Air-filled postcranial bones in theropod dinosaurs: physiological implications and the ‘reptile’–bird transition. _Biol. Rev._ 87, 168 (2012). Article Google Scholar * B. B. Britt

Thesis, University of Calgary (1993). * Wedel, M. J., Cifelli, R. I. & Sanders, R. K. Osteology, paleobiology, and relationships of the sauropod dinosaur. _Sauroposeidon. Acta

Palaeontol. Pol._ 45, 343 (2000). Google Scholar * Wedel, M. J. The evolution of vertebral pneumaticity in sauropod dinosaurs. _J. Vertebr. Paleontol._ 23, 344 (2003). Article Google

Scholar * Owen, R. On the _Archaeopteryx_ of von Meyer, with a description of a new long tailed species from the lithographic stone of Solenhofen. _Philosophical Transactions of the Royal

Society of London_ 153, 33 (1864). ADS Google Scholar * Kundrát, M., Nudds, M. J., Kear, B., Lü, J. & Ahlberg., P. The first specimen of _Archaeopteryx_ from the Upper Jurassic

Mörnsheim Formation of Germany. Historical. _Biology_ 1, 3 (2018). Google Scholar * Britt, B. B., Makovicky, P. J., Gauthier, J. & Bonde, N. Postcranial pneumatization in

_Archaeopteryx_. _Nature_ 395, 374 (1998). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Christiansen, P. & Bonde, N. Axial and appendicular pneumaticity in _Archaeopteryx_. _Proc. Roy. Soc.

Lond., Series B_ 267, 2501 (2000). Article CAS Google Scholar * Tischlinger, H. & Unwin, D. M. UV-Untersuchungen des Berliner Exemplars von _Archaeopteryx lithographica_ H. v. MEYER

1961 und der isolierten Archaeopteryx-Feder. _Archaeopteryx_ 22, 17 (2004). Google Scholar * Ostrom, J. H. _Archaeopteryx_ and the origin of birds. _Biological Journal of the Linnean

Society_ 8, 91 (1976). Article Google Scholar * Elzanowski, A. In _Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs_, Chiappe, L. & Witmer, L. M., Eds (University of California Press), pp.

129–159 (2002). * Tischlinger, H. Neue Informationen zum Berliner Exemplar von _Archaeopteryx lithographica_ H.v.Meyer 1861. New information regarding the Berlin example of Archaeopteryx

lithographica H.v.Meyer 1861. _Archaeopteryx_ 23, 33–50 (2005). Google Scholar * Hone, D. W. E., Tischlinger, H., Xu, X. & Zhang, F. The extent of the preserved feathers on the

four-winged dinosaur _Microraptor gui_ under ultraviolet light. _PLoS One_ 5, 1 (2010). Article Google Scholar * Rauhut, O. W. M., Foth, C., Tischlinger, H. & Norell, M. A.

Exceptionally preserved juvenile megalosauroid theropod dinosaur with filamentous integument from the Late Jurassic of Germany. _PNAS_ 109, 11746–11751 (2012). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * Tischlinger, H. & Arratia, G. Ultraviolet light as a tool for investigating Mesozoic fishes, with a focus on the ichthyofauna of the Solnhofen archipelago. in Mesozoic Fishes

5 – Global Diversity and Evolution, Arratia, G., Schultze, H.-P. & Wilson, H., Eds (Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München), pp. 549–560 (2013). * O’Connor, M. P. Pulmonary pneumaticity in

the postcranial skeleton of extant Aves: a case study examining Anseriformes. _J. Morphol._ 261, 141 (2004). Article Google Scholar * Martin, L. D. The beginning of the modern avian

radiation. Documents des Laboratoires de. _Geologie de la Faculte des Sciences de Lyon_ 99, 9–19 (1987). ADS Google Scholar * O’Connor, M. P. Evolution of archosaurian body plans: Skeletal

adaptations of an air-sac-based breathing apparatus in birds and other archosaurs. _J. Exp. Zool._ 311A, 629 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Mayr, G., Pohl, B., Hartman, S. & Peters,

D. S. The tenth skeletal specimen of _Archaeopteryx_. _Zool. J. Linn. Soc._ 149, 97 (2007). Article Google Scholar * Rauhut, O. W. M., Foth, C. & Tischlinger, H. The oldest

_Archaeopteryx_ (Theropoda: Avialae): a new specimen from the Kimmeridgian/Tithonian boundary of Schamhaupten, Bavaria. _PeerJ_ 6, e4191 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Wellnhofer, P.

_Archaeopteryx_. Der Urvogel von Solnhofen. (Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München), pp. 256 (2008). * Sereno, P. C. _et al_. Evidence for avian intrathoracic air sacs in a new predatory

dinosaur from Argentina. _PLoS One_ 3, e3303 (2008). Article ADS Google Scholar * Brochu, C. A. Osteology of _Tyrannosaurus rex_: insights from a nearly complete skeleton and

highresolution computed tomographic analysis of the skull. _Soc. Vertebr. Paleontol. Mem._ 7(22), 1 (2002). Google Scholar * Forster, C. A., Sampson, S. D., Chiappe, L. M. & Krause, D.

W. The theropod ancestry of birds: New Evidence from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. _Science_ 279, 1915 (1998). Article ADS CAS Google Scholar * Ewers, S. W., Rauhut, O. W. M.,

Milner, A. C., McFeeters, B. & Allain, R. A reappraisal of the morphology and systematic position of the theropod dinosaur _Sigilmassasaurus_ from the “middle” Cretaceous of Morocco.

_PeerJ_ 3, e1323 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Watanabe, A. _et al_. Vertebral pneumaticity in the ornithomimosaur _Archaeornithomimus_ (Dinosauria: Theropoda) revealed by computed

tomography imaging and reappraisal of axial pneumaticity in Ornithomimosauria. _PLoS One_ 10, e0145168 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Lü, J. _et al_. A new oviraptorid dinosaur

(Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of southern China and its paleobiological implications. _Sci. Rep._ 5, 11490 (2015). Article ADS Google Scholar * Lü, J. _et al_.

High diversity of the Ganzhou oviraptorid fauna increased by a new “cassowary-like” crested species. _Sci. Rep._ 7, 6393 (2017). Article ADS Google Scholar * Lü, J. C. A new

oviraptorosaurid (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of southern China. _J. Vertebr. Paleontol._ 22, 871 (2002). Article Google Scholar * Norell, M. A. & Makovicky,

P. J. Important features of the dromaeosaur skeleton. II. Information from newly collected specimens of _Velociraptor_. _Am. Mus. Novit._ 3282, 1 (1999). Google Scholar * Shen, C., Zhao,

B., Gao, C.-L., Lü, J. & Kundrát, M. A new troodontid dinosaur, _Liaoningvenator curriei_ gen. et sp. nov., from the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation of western Liaoning Province,

China. _Acta Geosci. Sin._ 38, 1–13 (2017). Google Scholar * Shen, C. _et al_. A new troodontid dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Liaoning Province. _China. Acta Geol.

Sin._ 91, 763–780 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Osmólska, H., Currie, P. J. & Barsbold, R. In The Dinosauria. 2nd ed., Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P. & Osmólska, H., Eds.

(University of California Press, Berkeley), pp. 165–183 (2004). * Chiappe, L. M., Shu’an, J. & Qiang, J. Anatomy and systematics of the Confuciusornithidae (Theropoda: Aves) from the

Late Mesozoic of Northeastern China. _Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist._ 242, 1 (1999). Google Scholar * Chiappe, L. M. & Walker, C. A. In _Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs_,

Chiappe, L. & Witmer, L. M., Eds (University of California Press), pp. 559–588 (2002). * Witmer, L. M. The craniofacial air sac system of mesozoic birds (Aves). _Zoological Journal of

the Linnean Society_ 100, 327 (1990). Article Google Scholar * Müller, B. The air sacs of the pigeon. Smithsonian Miscellaneous. _Collections_ 50, 365 (1908). Google Scholar *

Schwarz-Wings, D., Meyer, C. A., Frey, E., Manz-Steiner, H.-R. & Schumacher, R. Mechanics of pneumatic neck vertebrae in sauropod dinosaurs reveals a key role of vertebral pneumaticity

for achieving enormous body sizes. _Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. B_ 277, 11 (2010). Article Google Scholar * Fajardo, R. J., Hernandez, E. & O’Connor, M. P. Postcranial skeletal pneumaticity:

A case study in the use of quantitative microCT to assess vertebral structure in birds. _J. Anat._ 211, 138 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Erickson, G. M. _et al_. Was dinosaurian

physiology inherited by birds? Reconciling slow growth in _Archaeopteryx_. _PLoS One_ 4, e7390 (2009). Article ADS Google Scholar * Baumel, J. J. & Witmer, L. M. In _Handbook of Avian

Anatomy: Nomina Anatomica Avium_, Baumel, J. J., King, A. S., Breazile, J. E., Evans, H. E. & Vanden Berge, J. C., Eds (Nuttal Ornithological Club, Cambridge, Massachusetts), pp. 45–132

(1993). * Bellairs, A. D. A. & Jenkins, C. A. In _Biology and Comparative Physiology of Birds_, Marshall, A. J., Ed. (Academic Press, New York), vol. 1, pp. 241–300 (1960). * Hogg, D.

A. Fusions occurring in the postcranial skeleton of the domestic fowl. _J. Anat._ 135, 501 (1982). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Storer, R. W. Fused thoracic vertebrae in

birds: Their occurrence and possible significance. _J. Yamashina Inst. Ornithol._ 14, 86 (1982). Article Google Scholar * James, H. F. Repeated evolution of fused thoracic vertebrae in

songbirds. _The Auk_ 126, 862 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Kaiser, G. _The inner bird: Anatomy and Evolution_. (University of British Columbia) pp. 386 (2007). * Unwin, D. M.

_Pterosaurs from Deep Time_. (Pi Press, New York 2006). * Witton, M. P. _Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy_. (Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey), pp. 304

(2013). * Senter, P. Scapular orientation in theropods and basal birds, and the origin of flapping flight. _Acta Palaeont. Pol._ 51, 305 (2006). Google Scholar * Longrich, N. R., Vinther,

J., Meng, Q., Li, Q. & Russell, A. P. Primitive wing feather arrangement in _Archaeopteryx lithographica_ and _Anchiornis huxleyi_. _Curr. Biol._ 22, 2262 (2012). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Nudds, R. L. & Dyke, G. Narrow primary feather rachises in _Confuciusornis_ and _Archaeopteryx_ suggest poor flight ability. _Science_ 328, 887 (2010). Article ADS CAS

Google Scholar * Feo, T. J., Field, D. J. & Prum, R. O. Barb geometry of asymmetrical feathers reveals a transitional morphology in the evolution of avian flight. _Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond.

B_ 282, 20142864 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Cubo, J. & Casinos, A. Incidence and mechanical significance of pneumatization in the long bones of birds. _Zool. J. Linn. Soc.

Lond._ 130, 499 (2000). Article Google Scholar * Currey, J. D. & Alexander, R. M. The thickness of the walls of tubular bones. _J. Zool. Lond._ 206, 453 (1985). Article Google Scholar

Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Elke Siebert (MfN) for her help with scanning photographs, and the preparators Lutz Berner and Markus Brinkmann for their assistance in

handling the Berlin _Archaeopteryx_. We are grateful to Peter J. Makovicky and two other anonymous referees for their valuable comments and hints on earlier versions of this manuscript. MK

was supported by Scientific Grant Agency VEGA of the Ministry of the Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic (1/0853/17). GD acknowledges support from UEFISCDI Romania

[grant number PN-III-P4-ID-PCE-2016-0572]. The publication of this article was funded by the Open Access Fund of the Leibniz Association. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Museum

für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science, 10115, Berlin, Germany Daniela Schwarz * Center for Interdisciplinary Biosciences, Technology and Innovation Park,

University of Pavol Jozef Šafárik, 04154, Košice, Slovakia Martin Kundrát & Gareth Dyke * Tannenweg 16, 85134, Stammham, Germany Helmut Tischlinger * Department of Geology, Babes-Bolyai

University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Gareth Dyke * Department of Integrative Biology, University of South Florida, 33620, Tampa, FL, USA Ryan M. Carney Authors * Daniela Schwarz View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Martin Kundrát View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Helmut

Tischlinger View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Gareth Dyke View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Ryan M. Carney View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS D.S. and M.K. designed and performed the research; D.S., M.K.,

H.T., G.D. and R.C. contributed analytical tools and comparative data and/or discussed the manuscript during progress; D.S. and M.K. analyzed data; D.S., M.K., G.D. and R.C. wrote the paper.

CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Daniela Schwarz or Martin Kundrát. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

PUBLISHER’S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and

reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes

were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If

material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain

permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS

ARTICLE Schwarz, D., Kundrát, M., Tischlinger, H. _et al._ Ultraviolet light illuminates the avian nature of the Berlin _Archaeopteryx_ skeleton. _Sci Rep_ 9, 6518 (2019).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42823-5 Download citation * Received: 02 July 2018 * Accepted: 22 November 2018 * Published: 24 April 2019 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42823-5 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative