- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Lipids, including the diterpenes cafestol and kahweol, are key compounds that contribute to the quality of coffee beverages. We determined total lipid content and cafestol and

kahweol concentrations in green beans and genotyped 107 _Coffea arabica_ accessions, including wild genotypes from the historical FAO collection from Ethiopia. A genome-wide association

study was performed to identify genomic regions associated with lipid, cafestol and kahweol contents and cafestol/kahweol ratio. Using the diploid _Coffea canephora_ genome as a reference,

we identified 6,696 SNPs. Population structure analyses suggested the presence of two to three groups (K = 2 and K = 3) corresponding to the east and west sides of the Great Rift Valley and

an additional group formed by wild accessions collected in western forests. We identified 5 SNPs associated with lipid content, 4 with cafestol, 3 with kahweol and 9 with cafestol/kahweol

ratio. Most of these SNPs are located inside or near candidate genes related to metabolic pathways of these chemical compounds in coffee beans. In addition, three trait-associated SNPs

showed evidence of directional selection among cultivated and wild coffee accessions. Our results also confirm a great allelic richness in wild accessions from Ethiopia, especially in

accessions originating from forests in the west side of the Great Rift Valley. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS GENOMIC PREDICTIONS AND GENOME-WIDE ASSOCIATION STUDIES BASED ON RAD-SEQ

OF QUALITY-RELATED METABOLITES FOR THE GENOMICS-ASSISTED BREEDING OF TEA PLANTS Article Open access 15 October 2020 MINING GENOMIC REGIONS ASSOCIATED WITH AGRONOMIC AND BIOCHEMICAL TRAITS

IN QUINOA THROUGH GWAS Article Open access 22 April 2024 INTEGRATION OF GWAS AND TRANSCRIPTOME AND HAPLOTYPE ANALYSES TO IDENTIFY QTNS AND CANDIDATE GENES CONTROLLING OIL CONTENT IN SOYBEAN

SEEDS Article Open access 14 May 2025 INTRODUCTION Coffee beverage popularity is related to its unique aroma and flavor as well as its stimulant properties. The precursors of aroma and

flavor, which characterize the beverage, correspond to the chemical compounds of green coffee beans1. The concentrations of those components, such as sucrose, caffeine, chlorogenic acids and

lipids, are genetically controlled and can be selected to improve beverage quality2. Lipids are key compounds involved in flavor and aroma3. The coffee lipid fraction is mainly composed of

triacylglycerols, sterols, tocopherols and diterpenes. Cafestol (CAF), kahweol (KAH), and 16-O-methyl cafestol are the main diterpenes found in coffee oil4. These diterpenes, which are

specific to the _Coffea_ genus, have both desirable and adverse effects on human health5,6. Previous studies of CAF and KAH diterpenes in _Coffea arabica_ L. suggested a strong genetic

control of their biosynthesis2,7. Despite their importance, as far as we know, there is no study trying to correlate the variability of these biochemical compounds among accessions with

nucleotide diversity that would be of key interest to optimize coffee breeding strategies. The southwest Ethiopian highlands are the place of origin of _C_. _arabica_, and several landraces

of this species are known from this region8. To increase the diversity of _C_. _arabica_ breeding programs, research teams have been collecting accessions from various parts of Ethiopia

since 19289, transferring germplasm to other tropical countries. One important survey was organized by FAO in 1964–1965, and harvested seeds were sent to India, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Costa

Rica, Portugal, and Peru10. The Instituto Agronômico do Paraná (IAPAR - Londrina, PR, Brazil) received 132 of those accessions in 1976, which were planted and maintained to this day. The

accessions available in this collection show great phenotypic variation in plant architecture, and size of branches, leaves, fruits, and seeds. In relation to biotic and abiotic factors,

these coffee accessions exhibit various levels of tolerance and resistance11,12. In addition to these morphological and agronomical characteristics, these accessions present a large

variability in terms of biochemical contents in green beans, which often translates into a large range of beverage qualities2,12,13. _C_. _arabica_ is an allotetraploid (2n = 4 × = 44),

which is derived from a spontaneous hybridization between two closely related diploid species, _Coffea eugenioides_14 and _Coffea canephora_ Pierre ex A. Froehner15. Whereas _C_. _canephora_

(2n = 2 × = 22) is an allogamous diploid species harboring a high diversity16, the propagation history of _C_. _arabica_ combined with its autogamy has led to a narrow genetic diversity

among cultivars17. _C_. _arabica_ breeding programs suffered from this lack of diversity, which also hampered the development of molecular tools whose efficiency is recognized as maximizing

the genetic gains per unit of time. Genetic maps have only recently been reported for C. _arabica_18. However, there is no publicly available _C_. _arabica_ reference genome, even though a

few research efforts have been started. Nevertheless, a diploid genomic reference of _C_. _canephora_ has been released and has allowed significant progress for _C_. _arabica_ genomic

analyses19,20. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are an efficient approach to dissect the genetic architecture of complex traits21. GWAS usually provides a higher mapping-resolution

than classical biparental QTL mapping experiments, and is considered as a cost-effective way to detect associations between molecular markers and traits of interest21,22. However, assessing

the population structure of the association panel is necessary to minimize the occurrence of spurious associations21. GWAS requires the use of an adequate number of markers. Recently,

next-generation sequencing platforms have dramatically reduced the cost and time to obtain large numbers of markers. Because of its relative simplicity and robustness, the

genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) strategies have been extensively used21,22. In this study, our objectives were to (i) identify SNPs within _C_. _arabica_ genotypes based on GBS analyses; (ii)

analyze the population structure of the IAPAR collection of _C_. _arabica_ genotypes encompassing wild accessions; (iii) perform a GWAS to decipher the genetic basis of lipid and diterpene

contents within the broad-based Ethiopian collection; and (iv) draw consequences for coffee collections and _C_. _arabica_ breeding programs. RESULTS LIPID AND DITERPENE PROFILES The

complete list of 107 accessions analyzed in the present study is shown in Supplementary Table S1. We observed a high variability among the accessions for all traits analyzed (Table 1). There

was a negative correlation between cafestol (CAF) and kahweol (KAH) contents (r = −0.30, p-value < 0.005). KAH content showed a significant correlation with total lipid content (r =

0.29, p-value < 0.005), whereas CAF content showed no correlation with total lipids (r = 0.08, p-value > 0.005). GENOTYPING-BY-SEQUENCING AND SNP DETECTION Due to the lack of a _C_.

_arabica_ reference genome, we used the publicly available genome assembly of its ancestor _C_. _canephora_. This reference genome was used to map the GBS tags and perform the SNP calling.

GBS libraries yielded approximately 48 million single-end reads. Those reads produced 6,210,920 tags, of which 20% were aligned to unique positions. A total of 6,696 SNPs was identified,

with an average depth of 39×. The SNPs were filtered based on minor allele frequency (MAF > 0.05) and call rate (>0.80). Thereafter, the resulting SNPs were filtered based on their

heterozygosity (Ho): SNPs with Ho >0.9 were discarded. Filtering based on Ho was performed in order to eliminate SNPs deriving from _C_. _arabica_ homeologous genomic regions in which

different alleles are fixed in the two subgenomes (CaCe vs CaCc)23. A final set of 2,587 SNPs were obtained and used for further population structure and genome wide association analysis for

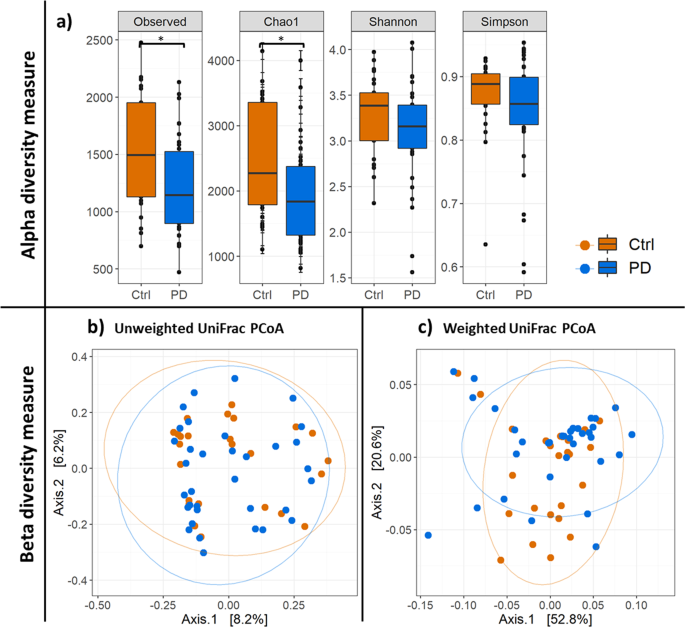

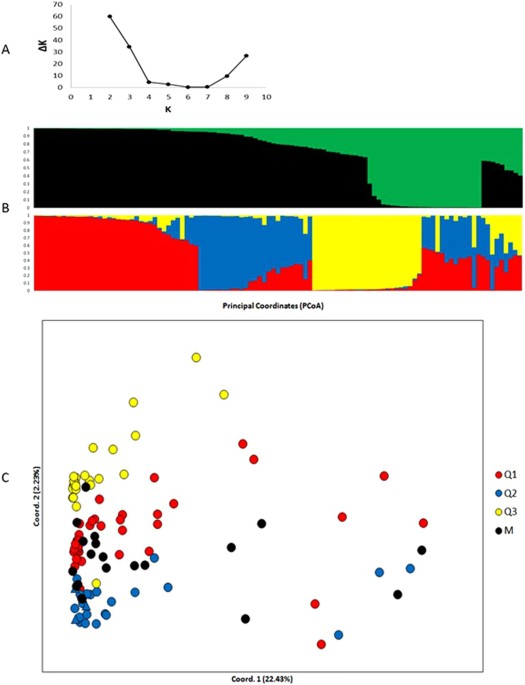

the lipids and diterpenes contents. POPULATION STRUCTURE OF THE COLLECTION Population structure analysis was performed using a Bayesian model-based approach implemented in STRUCTURE

software (Fig. 1A). The STRUCTURE results based on three groups (K = 3) showed a high ΔK value, but the upper-most level of the structure was in two groups (K = 2) based on the Evanno

criterion24. The structure result using K = 2 (Fig. 1B) grouped all cultivars and accessions from the east side of the Great Rift Valley in the Q1 group (black). Meanwhile, the Q2 group

(green) was exclusively composed of wild accessions from the west side of the Great Rift Valley. On the other hand, the structure result using K = 3 formed a Q1 group (red) composed of 37

genotypes from the west side of the Great Rift Valley. The Q2 group (blue) was formed by three traditional cultivars (Bourbon, Typica and Mundo Novo), five accessions from the east and 16

from the west side of the Great Rift Valley. The Q3 group (yellow) was composed of 25 genotypes, all wild accessions collected in the forests of western Ethiopia. The mixed group (M,

individuals with admixture higher than 0.4) included nine accessions from the West side of the Great Rift Valley. In a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), the first two coordinates

explained 25% of the total genetic variation (Fig. 1C). Similar to the STRUCTURE analysis, traditional cultivars were genetically closer to eastern Ethiopian genotypes than western Ethiopian

genotypes. The M group presented the highest intragroup diversity, showing an allele number average (Na), Shannon’s information index (I) and expected heterozygosity (He) mean of 1.97,

0.55, and 0.37, respectively (see Supplementary Table S2). This result can be explained by the fact that the M group is composed of mixed individuals. In the Q1, Q2, and Q3 groups, we

observed 11, 15, and 6 private alleles, respectively. The M group did not contain private alleles. The most homogeneous and distant group in relation to the others was Q3, formed exclusively

by wild accessions collected in forests of western Ethiopia. Comparing lipid, CAF, and KAH contents and CAF/KAH ratio among genetic groups (Fig. 2), we observed that the group composed of

wild accessions (Q3) presented lower ranges of variation for all traits. In addition, according to ANOVA, Q3 had a higher lipid content than the other groups (p-value < 0.05). On the

other hand, the M group presented a wide range of variation in all traits. The accessions with lower phenotypic values for all traits were sorted into the M group. LINKAGE DISEQUILIBRIUM

ANALYSIS The parameters r2 and r2vs were estimated as a function of the physical distance between loci. We observed a linkage disequilibrium (r2vs, corrected for population structure and

bias due to relatedness) decay below 0.2 at 185 Kbp (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Considering the values of r2 (uncorrected), we observe a linkage disequilibrium decay below r2 = 0.2 at 298

Kbp. With the r2vs measure, lower values overall were obtained, as well as an expected exponential decline of linkage disequilibrium with distance, which demonstrated the efficiency of this

measure in correcting bias. We also observed a difference between the estimated r2 and r2vs. The positive bias was removed across the whole chromosomal segment. However, for some close loci,

the r2vs estimate was larger than r2, leading to the removal of negative bias, as well. It is important to note that LD was calculated using the _C_. _canephora_ ancestral genome as a

reference, since there is no Arabica genome available. GENOME-WIDE ASSOCIATION MAPPING FOR LIPIDS AND DITERPENES To identify genomic regions associated with natural variation in lipids and

diterpenes content in _C_. _arabica_ beans, we performed GWAS using four different methods (mrMLM, ISIS EM-BLASSO, pLARmEB, and FASTmrEMMA) with 107 accessions. We identified a total of 21

SNPs associated with lipid (5), CAF (4), and KAH (3) contents and CAF/KAH ratio (9), which were distributed among all chromosomes (Table 2, and Supplementary Figures 1–4). Nine SNPs were

associated with the traits analyzed by at least two methods. Two SNPs, one for CAF and one for KAH were identified by three methods (mrMLM, pLARmEB, ISIS EM-BLASSO). Using FASTmrEMMA method,

no SNP was significantly associated. On the other hand, ISIS EM-BLASSO and pLARmEB were the methods identifying a high number of associated SNPs, 13 and 16 respectively. CANDIDATE GENES

CO-LOCALIZED WITH LIPID- AND DITERPENE-ASSOCIATED SNPS For candidate gene mining, we considered only SNPs associated with traits that were detected by at least two methods. Remarkably, we

found SNPs positioned within or near genomic regions coding for proteins involved in lipids and diterpenes metabolic pathways (Table 3). RNA-seq data obtained from coffee leaves, flowers and

fruit tissues from 30 to 150 days after flowering (DAF) from a previous study25 were used to explore the gene expression patterns of some of the candidate genes identified (Fig. 3).

Interestingly, with one exception (_BTAF1_), all the genes showed stronger expression profile in flowers and or fruit organs. GENOMIC SIGNATURES OF SELECTION AMONG GENETIC GROUPS Among 2,587

SNPs analysed, 139 present signature of diversifying selection among genetic groups (Q1, Q2, and Q3), according with BAYESCAN results (Fig. 4). Three of these SNPs were also identified as

being associated with some of the traits analyzed in the GWAS. The frequency of the alternative alleles of these loci in the Q3 group, formed by wild accessions and collected in the western

forests of Ethiopia, was very low compared to the Q1 group, which was composed of domesticated accessions with intermediate levels of breeding (Table 4) and the Q2 group, which is composed

of accessions with higher levels of breeding, including traditional cultivars Typica, Bourbon, and Mundo Novo. DISCUSSION PHENOTYPIC ANALYSIS The 107 genotypes analyzed presented high

phenotypic variability for the lipid, CAF and KAH contents and for the CAF/KAH ratio. Other studies also report high genetic diversity in _C_. _arabica_ accessions from primary diversity

centers for bean physical, organoleptic and biochemical qualities displaying high variability2,13. According to these studies, the influence of geographical origin on these traits was

evident. Interestingly, in the present study a large influence of the geographic origin on CAF, KAH and lipid contents in the beans was also observed. Wild accessions collected in the

forests of the west side of Great Rift Valley presented higher lipid contents than cultivars. Although biochemical compounds related to beverage quality traits in coffee, including lipid and

diterpene contents2,7,12, have been already described, this is the first large-scale study using an Arabica population that includes several wild accessions from Ethiopia. Accessions with

different lipid and diterpene contents may serve as a source of alleles for the development of plants with desirable lipid and diterpene contents in the beans. Therefore, the results of the

present study can contribute to coffee breeding to deliver high-quality coffee varieties according to the consumer market demands. GENOTYPING-BY-SEQUENCING AND SNP DETECTION We used the

diploid genome of _C_. _canephora_19 as a reference to find SNP markers in the _C_. _arabica_ genome. The high degree of conservation between both genomes is well known15,26 and allowed us

to map tags from genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) data for SNP identification. We identified a total of 6,696 SNPs. Those SNPs were further filtered for MAF, call rate and heterozygosity,

generating 2,587 high quality SNPs for population structure and genome-wide association analyses. One of the main difficulties of working with polyploids is distinguishing true SNPs

segregating in the subgenomes from homologous SNPs representing fixed differences between both ancestral diploids subgenomes23. Therefore, SNPs corresponding to the differences between both

subgenomes (heterozygosity = 1) were discarded and the SNPs selected represent true variability in _C_. _arabica_. The number of detected SNPs was relatively low. This can be explained by

the low genetic diversity of the species, which has a recent origin15. In addition, we used just one subgenome as a reference, and the number of TAGs mapped was low (22%). However, in a

recent similar study using GBS in _C_. _canephora_, only 32% of TAGs were mapped using the same _C_. _canephora_ genome reference27. GENETIC DIVERSITY AND POPULATION STRUCTURE Despite the

wide geographical range of Arabica coffee cultivation, the number of cultivars used is very small: mainly _C_. _arabica_ var. Typica, _C_. _arabica_ var. Bourbon, their mutants and

hybrids28. The narrow genetic base of those cultivars9 has resulted in a crop with homogenous agronomic behaviors15, including high susceptibility to biotic and climatic stress29

representing a breeding challenge due environmental changes or market demands. The genetic diversity analysis using SNP markers revealed that the collection of _C_. _arabica_ used in this

study has a higher genetic diversity than traditional cultivars, consistent with the great phenotypic variability observed for the biochemical characterization previously reported2,7,12. In

this context, our Ethiopian germplasm collection has been shown to be a valuable source of novel favorable biochemical characteristic-related alleles, which can be explored by breeding

programs. In the STRUCTURE analysis using K = 3, all cultivars and genotypes from the east side of the Great Rift Valley were sorted into the same group (Q2). Previous genotypic

characterization of this collection using microsatellite markers showed a subdivision of these genotypes only into two groups, from the west and east sides of the Rift Valley9,11.

Interestingly, the Q3 group, formed by wild accessions, presented a high lipid content in comparison to the other groups. This result indicates that the Q3 group contains alleles conferring

differentiated lipid content in beans. In Ethiopia, this wild gene pool has been potentially threatened by forest fragmentation and degradation and by introgressive hybridization with

locally improved coffee varieties30. Our results reinforce the importance of preserving the germplasm of _C_. _arabica_ from the origin center (Ethiopia). Both forest fragmentation and

forest degradation can have a negative impact on the genetic diversity of forest plant species through increased genetic drift, reduced gene flow, and alteration of mating patterns resulting

in increased inbreeding31,32. In addition, the widespread planting since the 1970s of a restricted set of locally improved coffee varieties, mainly genotypes resistant to coffee berry

disease, in the forest and its surroundings may result in the replacement of a part of the wild gene pool with a small number of domesticated alleles33,34. This can result in loss of genetic

variation from the original gene pool and may even have negative fitness consequences for the original populations35. Overall, our results can help us to define which accessions are more

important to preserve in order to have a good genetic representation of the FAO collection. The genetic diversity of plants from the western region demonstrated the importance of carefully

preserving and exploring the accessions from this region in order to increase genetic variability, especially for coffee beverage quality12. It is important to observe that our work was

performed only with a subset of the full FAO collection. Studies using the whole collection and or focusing in the genotypes from the Western side of Great Rift Valley would be of great

value for increase our knowledge on the phenotypic and genotypic diversity of _C_. _arabica_. GENOME-WIDE ASSOCIATION STUDY Several studies relating quantitative trait loci (QTLs) to cup

quality compounds have been performed on _C_. _canephora_35 and other _Coffea_ species36, but none has been reported for _C_. _arabica_. We performed GWAS for lipids and CAF and KAH

diterpenes in coffee beans using 104 accessions from the FAO Ethiopian collection and three cultivars. We used 2,587 high-quality SNPs and identified 21 SNP/trait associations. A common

feature of the MLM-based GWAS methods is the one-dimensional genome scan, performed by testing one marker at a time. However, such a model does not facilitate good estimates of marker

effects because the model is never correct if a trait is indeed controlled by multiple loci, which is the case for most complex traits37. Another problem with the method is the issue of

multiple test corrections for the threshold value of significance testing. The typical Bonferroni correction is often too conservative, so many important loci may not pass the stringent

criterion of significance testing37. The mrMLM method was efficient to identify genomic regions associated with lipid and diterpenes concentrations in coffee green beans, combining an

efficient control of false positives with high power, as described by the authors of this method37. CANDIDATE GENES CO-LOCALIZED WITH LIPID-ASSOCIATED SNPS Coffee bean lipids are composed

mainly of triacylglycerols, sterols and tocopherols, the typical components found in all common edible vegetable oils4. Insights into the details of lipid biosynthesis and information on the

genes and enzymes involved in this process may lead to innovative strategies to modify the fatty acid composition and increase seed oil content. In the present study, we identified one

lipid-associated SNP (S8_25559761) co-localized with the _Cc08_g10680_ gene, which encodes a fatty acid desaturase (_FAD2_). Desaturase enzymes regulate the unsaturation of fatty acids

through the introduction of double bonds between defined carbons of the fatty acyl chain. Very interestingly, the difference of diterpenes CAF and KAH is just one unsaturated carbon38,

therefore the potential role of _FAD2_ in KAH formation should be further investigated. In _Arabidopsis thaliana_, _FAD2_ has been shown to be important in the seed oil biosynthesis

pathway39. This gene was identified as associated with lipid content in corn grains40 and brassica41. CANDIDATE GENES CO-LOCALIZED WITH DITERPENE-ASSOCIATED SNPS All plant diterpenoids are

derived from only two five-carbon (C5) isoprenoids, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP), and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), produced via the cytosolic mevalonate (MVA) and the plastidial

2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathways38. Sequential condensation of these units by transferases yields a handful of central prenyl diphosphate intermediates in terpenoid

biosynthesis. Diterpenoids originate predominantly from the MEP pathway. KAH and CAF are exclusive diterpenes of the _Coffea_ genus7. They have a very similar chemical structure with one

double bond difference in the aromatic hydrocarbon composed by twenty carbons38. In contrast to other biochemical compounds, the total amount of diterpenes does not significantly change

among cropping years and environments2, suggesting that the production of these compounds is under strong genetic control. Terpene diversification is driven by the machinery consisting TPSs

and cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenases (_CYP_) genes. The latter is important for modifying and diversifying the terpenoid scaffolds by redox modification42. We identified one SNP

associated with CAF (S11_29778697) that was co-localized with the gene Cc11_g12750, which encodes a cytochrome P450 704 (_CYP704_). Several _P450_ genes are involved in secondary metabolite

biosynthesis, including terpenoids43,44. _CYP704_ in rice was also shown to provide lipid monomers for the synthesis of anther cutin45. Another SNP associated with CAF is positioned close to

a monooxygenase. Monooxygenase was described as being directly involved in plant terpene biosynthesis46. The SNP S2_45775221 associated with KAH is co-localized with Cc02_g33380, which

encodes a long chain acyl-CoA synthetase (_LACS_). LACS proteins occupy a critical position in the biosynthetic pathways of nearly all fatty acid-derived molecules47. LACS proteins esterify

free fatty acids to acyl-CoAs, a key activation step that is necessary for the utilization of fatty acids by most lipid metabolic enzymes. LACS proteins initiate the process of fatty acid

β-oxidation. In oilseeds, carbon reserves are stored as triacylglycerol (TAG). With the onset of germination, lipases release free fatty acids from the TAG molecules. LACS proteins activate

the free fatty acids to acyl-CoAs that enter the β-oxidation pathway in the glyoxysomes of the germinating seedling. The enzymes of the β-oxidation cycle completely degrade fatty acids by

the sequential removal of two-carbon units, which are released in the form of acetyl-CoA. The resulting acetyl-CoA pool is essential for the production of cellular energy (through the

tricarboxylic acid cycle) and for synthesis of sugars and other carbon skeletons. LACS were also identified as being associated with lipid content in maize40 and brassica48. Among SNPs

associated with the CAF/KAH ratio, one is co-localized with the gene Cc06_g14660, which encodes a diterpene synthase (momilactone A synthase). Momilactone A is a diterpenoid secondary

metabolite that is involved in the defense mechanism of the plant49. In rice, a dehydrogenase also has been suggested to be involved in momilactone biosynthesis50. The SNP S2_48526210 is

co-localized with the gene Cc02_g34890, which encodes a dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase (lpdA). LpdA encoding the E3 subunits of both the pyruvate dehydrogenase and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase

complexes51. As already demonstrated in the phenotypic analysis, the CAF/KAH ratio is significantly correlated with lipid content, and this could explain why some SNPs associated with lipid

content are also co-localized with genes related to lipid metabolism. In addition, the initial steps of CAF and KAH biosynthesis use acetyl-CoA as a substrate38. One SNP associated with

CAF/KAH ratio (S7_5138106) is co-localized with the gene Cc07_g06960, which encodes an acyl-CoA N-acyltransferases (_NAT_). N-Acyltransferase catalyzes the transfer of an acyl group to a

substrate. Members of the N-acyltransferase superfamily have a similar catalytic mechanism but vary in the types of acyl groups they transfer, including those of the three main nutrient

substances, saccharides, lipids and proteins. These substances participate in a common metabolic pathway mediated by acetyl-CoA in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation

reactions. Acyl lipids have various functions in plants, and the structures and properties of the acyl lipids vary greatly even though they are all derived from the same fatty acid and

glycerolipid biosynthesis pathway. Some acyl lipids, including jasmonic acid, participate in signaling pathways. Acyl-CoA and acyl-CoA N-acyltransferase are involved in these metabolic

pathways, including pyruvate dehydrogenase and pyruvate, and they are involved in the metabolism of sugars in the citric acid cycle and fatty acids and fat metabolism required for the

synthesis of flavonoids and related polyketides for the elongation of fatty acids involved in sesquiterpenes, brassinosteroids, and membrane sterols47. We identified a SNP associated with

CAF/KAH ratio (S2_15335417) that co-localized with the Cc02_g16540 gene, which encodes a plastidial triosephosphate isomerase (_pdTPI_). After germination, seedling establishment requires a

transition from heterotrophic to autotrophic growth to sustain plant growth once storage reserves are used. This likely involves multiple plastid biosynthetic pathways. In plants, triose

phosphate isomerase (TPIP; EC 5.3.1.1) is involved in several metabolic pathways operating during this transition, including glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and the Calvin cycle52. In

_Arabidopsis_, a plastid isoform of triose phosphate isomerase (_pdTPIP_) plays a crucial role in the transition from heterotrophic to autotrophic growth54. A T-DNA insertion in _Arabidopsis

thaliana pdTPIP_ resulted in a fivefold reduction in transcription, reduced _TPIP_ activity, and a severely stunted and chlorotic seedling that accumulated dihydroxyacetone phosphate

(_DHAP_), glycerol, and glycerol-3-phosphate53. We observed the transcription pattern of the genes co-localized with associated SNPs. With one exception (_BTAF1_), the transcriptional data

strongly corroborates to diterpene biochemical profile reported for the same organs7,25. Diterpenes are present mainly in roots, flowers and accumulated in fruits during its development

reaching a peak around 120 DAF7. In flowers the presence of CAF is predominant and it will be very interesting to study the role of the _MAS_ in CAF formation. Meanwhile _FADS2_, _CYP704_

and _TPIP1_, showed a transcription pattern similar to KAH accumulation during coffee fruit development. The role of _FCM_, strongly expressed in the final stages of fruit maturation, also

can be very interestingly with a potential role in the final composition of lipids in coffee grains. Among all trait-associated SNPs detected by GWAS, three showed strong signals of

directional selection between genetic groups identified using STRUCTURE with K = 3 (S4_3861777, S2_45775221, and S11_29778697). The Q3 group (wild accessions) presented very low frequencies

of the reference alleles at these loci when compared to the Q1 group and especially compared to the Q2 group, which is composed of cultivated accessions. These observations indicate that

domestication and the breeding process of _C_. _arabica_ may have changed allelic frequencies of these loci in order to modulate lipids and diterpenes content, possibly resulting in

differentiated beverages. In addition, lipids and terpenes are known as chemical compounds related to plant defense against herbivory, response to abiotic stress and coffee flavor1,54, all

of which can also be related to the Arabica domestication process. In summary, these findings identify candidate genes representing potential targets for improving beverage quality in

relation to lipids and diterpenes composition. The information reported here can be a starting point to obtain plants with desirable content of lipids, CAF, and KAH by incorporating

molecular breeding techniques to the traditional programs. Our analyses also allowed assessing the population structure and genetic relationships among genotypes of a _C_. _arabica_

germplasm collection originated from FAO surveys in the 1960’s. We identified a great allelic richness in the accessions of Ethiopia, especially in the West side of the Great Rift Valley.

Trait-associated-SNPs identified by GWAS may be helpful to develop Markers Assisted Selection strategies aiming to improve the biochemical quality of the coffee beans. METHODS PLANT MATERIAL

The complete list of 107 accessions analyzed in the present study is shown in Supplementary Table S1. The FAO Ethiopian _C_. _arabica_ collection as well as cultivars from the Instituto

Agronômico do Paraná (IAPAR) breeding program were cultivated at its experimental station in Londrina, Brazil (23°23′00″S and 51°11′30″W). The soil is a red dystrophic latosol, and the

average rainfall and temperature are 1,500 mm/year and 21 °C, respectively. The FAO collection at IAPAR comes from open-pollinated seeds from the original collection at CATIE (Costa Rica)

introduced in Brazil in 1976, and kindly transferred from the Instituto Agronômico de Campinas (IAC) to IAPAR. Fruits were harvested from 107 genotypes between May to July 2011 at full

maturity. Cherries were manually selected in order to avoid immature and damaged seeds, which were washed and sun-dried until they contained 12% moisture. Coffee beans were processed (husk

and parchment removal) and standardized in grade 16-sized sieves (6.5 mm); all defective beans were discarded. PHENOTYPING FOR LIPID AND DITERPENE CONTENTS Coffee beans were frozen using

liquid nitrogen to prevent compound oxidation in the matrix and ground (0.5 mm particles) in a disk mill (PERTEN 3600, Kungens Kurva, Sweden). The milled samples were stored in plastic bags

and kept in a freezer (−18 °C) until analysis. The moisture content (oven set at 105 °C to constant weight) was also determined to express the results in terms of dry weight. Cafestol (CAF)

and kahweol (KAH) were analyzed by direct extraction using saponification and cleanup in terc-butyl-methyl-ether and water2. The extracts were identified and quantified by HPLC at 220 and

290 nm for CAF and KAH, respectively. A reversed-phase Spherisorb ODS 1 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm id 5 mm) (Waters, Milford, USA) and an acetonitrile: water (55:45) mobile phase were used to

separate the compounds. Quantification was carried out by external standardization, generating calibration curves with CAF and KAH content between 50 and 1,000 mg.100 g−1 (six different

concentrations in triplicate). To determine the lipid content of ground coffee beans, the methods described in the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC)55 using petroleum ether

as a solvent was employed. GENOTYPING-BY-SEQUENCING DNA extractions were performed from leaves using a modified CTAB protocol56. GBS was performed by the Genomic Diversity Facility LIMS at

Cornell University. The _PstI_ restriction enzyme was used for library preparation57. Single-end sequencing of multiplexed GBS libraries were performed on Illumina HiSeq 2000 equipment, with

159 samples in two 96-well multiplex plates. Single nucleotide polymorphisms were identified using the TASSEL-GBS pipeline58 in TASSEL software version 3.0.166. Briefly, raw FASTQ sequences

were trimmed to remove barcodes and reads from each of the four FASTQ files were collapsed into one master TagCounts file containing unique tags along with their associated read count

information. Tags aligned to unique positions on the _C_. _canephora_ reference genome19 were used for SNP calling. SNP discovery was performed for each set of tags that aligned to the exact

same starting genomic position and strand. SNP genotyping was determined by the default binomial likelihood ratio method of quantitative SNP calling in TASSEL 3.0.16658. GBS SNP calling was

performed using the _C_. _canephora_ genome as reference. Quality control of the SNPs was performed using the parameters of call rate (CR > 80%), minor allele frequency (MAF > 5%),

and heterozygosity (Ho < 0.9). ASSESSMENT OF GENETIC DIVERSITY USING SNP MARKERS According to the whole set of SNP, we estimated mean number of alleles (Na), percentage of polymorphic

loci (P), expected heterozygosity (He), Shannon’s information index (I) and number of private alleles in each genetic group using GenAlEx 6 software59. POPULATION STRUCTURE ANALYSIS We

performed principal coordinate analyses (PCoAs) via covariance matrices with data standardization using GenAlEx 6 software to assess and visualize genetic relationships among genetic groups

and individuals. Genetic structure was estimated using the model-based Bayesian method implemented in STRUCTURE software version 2.3.460. Allele frequencies of each K cluster (from 2 to 10)

were estimated. We assumed a single domestication event and restricted our analysis to the correlated frequency model. We used a 105 burn-in period and 105 iterations, as these parameters

resulted in relative stability of the results with 10 runs per K value. The genome composition (genome plot) of the accessions was represented for each K. Only accessions displaying a

membership larger than 0.6 were assigned to a genetic group, resulting in assignments for 80% of the accessions. Accessions with memberships lower than 0.6 were assigned to a mixed cluster

(M). We used the _ΔK_ criterion24 in Structure Harvester software61 to estimate the upper-most level of structure. LINKAGE DISEQUILIBRIUM ANALYSIS Pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD)

between SNP markers was calculated to evaluate the extent of LD decay. Only pairs of markers with distances at most 20 Mbp from each other were considered. LD was estimated using the

parameter r2vs obtained by considering the population structure and cryptic relatedness using the R package ‘LDcorSV’ version 1.3.162. An identity-by-state (IBS) centered kinship matrix was

calculated using TASSEL software version 5.2.2063. A population structure matrix (Q matrix) was obtained using STRUCTURE software version 2.3.461 (K = 2). GENOME-WIDE ASSOCIATION MAPPING FOR

LIPIDS AND DITERPENES To identify SNPs and candidate genes associated with natural variation in lipid and diterpene contents in Arabica beans, we performed GWAS using four methods:

multi-locus random-SNP-effect mixed linear model (mrMLM), FAST multi-locus random-SNP-effect EMMA (FASTmrEMMA), integrative sure independence screening EM-Bayesian LASSO (ISIS EM-BLASSO),

and polygenic-background-control-based least angle regression plus empirical Bayes (pLARmEB). The mrMLM method used a random-SNP-effect MLM (RMLM) and a multi-locus RMLM (mrMLM) for GWAS.

The mrMLM treats the SNP-effect as random, but it allows a modified Bonferroni correction to calculate the threshold p-value for significance tests. The mrMLM is a multi-locus model

including markers selected from the RMLM method with a less stringent selection criterion. Due to the multi-locus nature, no multiple test correction is needed. The results from real data

analyses and simulation studies show that the mrMLM has the highest power for quantitative trait nucleotide QTN detection, the best fit for genetic models, the minimal bias in the estimation

of the QTN effect, and the strongest robustness, compared with the RMLM and the EMMA37. For the mrMLM method, the parameters used were critical p-value in rMLM = 0.01, search radius of

candidate gene (Kb) = 20, critical LOD score in mrMLM = 3. In the FASTmrEMMA method, a new matrix transformation is constructed to obtain a new genetic model that includes only QTN variation

and normal residual error; allowing the number of nonzero eigenvalues to be one and fixing the polygenic-to-residual variance ratio is used to increase computing speed65. All the putative

QTNs with the ≤0.005 p-values in the first step of the new method are included in one multi-locus model for true QTN detection. Owing to the multi-locus feature, the Bonferroni correction is

replaced by a less stringent selection criterion. The results from analyses of both simulated and real data showed that FASTmrEMMA is more powerful in QTN detection, model fit and

robustness, has less bias in QTN effect estimation, and requires less running time than the current single- and multi-locus methodologies for GWAS, such as E-BAYES, SUPER, EMMA, CMLM and

ECMLM64. For FASTmrEMMA, we used the critical p-value in the first step of FASTmrEMMA = 0.005 and critical LOD score in the last step of FASTmrEMMA = 364. ISIS EM-BLASSO uses an iterative

modified-sure independence screening (ISIS) approach in reducing the number of SNPs to a moderate size65. Expectation-maximization (EM)-Bayesian least absolute shrinkage and selection

operator (BLASSO) is used to estimate all the selected SNP effects for true quantitative trait nucleotide (QTN) detection. Monte Carlo simulation studies validated this method, which has the

highest empirical power in QTN detection and the highest accuracy in QTN effect estimation, and it is the fastest, compared to the efficient mixed-model association (EMMA), smoothly clipped

absolute deviation (SCAD), fixed and random model circulating probability unification (FarmCPU), and multi-locus random-SNP-effect mixed linear model (mrMLM)65. For the ISIS EM-BLASSO

method, we considered a critical p-value = 0.01. The pLARmEB method integrates a least angle regression with empirical Bayes to perform multi-locus GWAS under polygenic background control66

using an algorithm of model transformation that whitened the covariance matrix of the polygenic matrix K and environmental noise. Markers on one chromosome are included simultaneously in a

multi-locus model and least angle regression is used to select the most potentially associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), whereas the markers on the other chromosomes are used

to calculate a kinship matrix as a polygenic background control. The selected SNPs in the multi-locus model are further detected for their association with the trait by empirical Bayes and

likelihood ratio test. The results from the simulation studies showed that pLARmEB was more powerful in QTN detection and more accurate in QTN effect estimation, had lower false positive

rates and required less computing time than Bayesian hierarchical generalized linear model, efficient mixed model association (EMMA) and least angle regression plus empirical Bayes. For the

pLARmEB method, the parameters used were critical LOD score = 2 and the number of potentially associated variables selected by LARS = 50. All these analyses were performed using the mrMLM

package37 in the R program. To control the effect of population structure, we used a Q matrix generated by STRUCTURE software considering K = 2. To control the bias generated by the kinship

effects between individuals, an identity by state (IBS) kinship matrix was used. The Coffee Genome Hub database20 was used to identify _C_. _canephora_ genes located in the interval of 100

Kbp encompassing significant SNPs. The digital gene expression pattern was obtained using RPKM values from coffee leaves, flowers and fruit tissues from 30 to 150 days after flowering

published in a previous study25. Graphic were developed using Genesis Software version 1.8.167. DETECTION OF SNPS UNDER DIRECTIONAL SELECTION AMONG GENETIC GROUPS To detect loci under

directional selection among genetic groups identified using STRUCTURE analysis, we used the Bayesian approach of BAYESCAN 2.0168. BAYESCAN was run with burn-in = 50,000, thinning interval =

30, sample size = 5,000, number of pilot runs = 50, length of pilot runs = 5,000, and the false discovery rate (FDR) threshold 0.1. REFERENCES * Selmar, D., Bytof, G. & Knopp, S. E. The

storage of green coffee (_Coffea arabica_ L.): Decrease of viability and changes of potential aroma precursors. _Ann. Bot._ 101, 31–38 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Scholz,

M. B. S. _et al_. Chemical composition in wild Ethiopian Arabica coffee accessions. _Euphytica_ 209, 429–438 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kreuml, M. T. L., Majchrzak, D.,

Ploederl, B. & Koenig, J. Changes in sensory quality characteristics of coffee during storage. _Food Sci. Nutr._ 4, 267–272 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Speer, K. &

Kolling-Speer, I. The lipid fraction of the coffee bean. _Braz. J. Plant Physiol._ 18, 201–216 (2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * Chu, Y. F. _et al_. Type 2 diabetes-related

bioactivities of coffee: assessment of antioxidant activity, NF-κB inhibition, and stimulation of glucose uptake. _Food Chem._ 124, 914–920 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sridevi,

V., Giridhar, P. & Ravishankar, G. A. Evaluation of roasting and brewing effect on antinutritional diterpenes-cafestol and kahweol in coffee. _Glob. J. Med. Res._ 11, 16–22 (2011).

Google Scholar * Ivamoto, S. T. _et al_. Diterpenes biochemical profile and transcriptional analysis of cytochrome P450s genes in leaves, roots, flowers, and during _Coffea arabica_ L.

fruit development. _Plant Physiol. Biochem._ 111, 340–347 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Meyer, G. F. Notes on wild _Coffea arabica_ from Southwestern Ethiopia, with some

historical considerations. _Econ. Bot._ 19, 136–151 (1965). Article Google Scholar * Anthony, F. _et al_. Genetic diversity of wild coffee (_Coffea arabica_ L.) using molecular markers.

_Euphytica_ 118, 53–65 (2001). Article CAS Google Scholar * Meyer, F. G. _et al_. FAO coffee mission to Ethiopia 1964–1965. FAO, Rome (1968). * Silvestrini, M. _et al_. Genetic diversity

and structure of Ethiopian, Yemen and Brazilian _Coffea arabica_ L. accessions using microsatellites markers. _Genet. Resour. Crop Ev._ 54, 1367–1379 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Tran, H. T. M. _et al_. Variation in bean morphology and biochemical composition measured in different genetic groups of arabica coffee (_Coffea arabica_ L.). _Tree Genet. Genom._ 13, 54

(2017). Article Google Scholar * Tessema, A., Alamerew, S., Kufa, T. & Garedew, W. Genetic diversity analysis for quality attributes of some promising _Coffea arabica_ germplasm

collections in Southwestern Ethiopia. _J. Biol. Sci._ 11, 236–244 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Yuyama, P. M. _et al_. Transcriptome analysis in _Coffea eugenioides_, an Arabica coffee

ancestor, reveals differentially expressed genes in leaves and fruits. _Mol_. _Gen_. _Genomics_ 291, 323–336 (2016). CAS Google Scholar * Lashermes, P. _et al_. Molecular characterization

and origin of the _Coffea arabica_ L. genome. _Mol. Gen. Genet._ 261, 259–266 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Musoli, P. _et al_. Genetic differentiation of wild and

cultivated populations: diversity of _Coffea canephora_ Pierre in Uganda. _Genome_ 52, 34–46 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Steiger, D. L. _et al_. AFLP analysis of genetic diversity

within and among _Coffea arabica_ varieties. _Theor. Appl. Genet._ 105, 209–215 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Moncada, P. _et al_. A genetic linkage map of coffee (_Coffea

arabica_ L.) and QTL for yield, plant height, and bean size. _Tree Genet. Genom._ 12, 5 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Denoeud, F. _et al_. The coffee genome provides insight into the

convergent evolution of caffeine biosynthesis. _Science_ 345, 1181–1184 (2014). Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dereeper, A. _et al_. The coffee genome hub: a resource for

coffee genomes. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 43, 1028–1035 (2015). Article Google Scholar * Korte, A. & Farlow, A. The advantages and limitations of trait analysis with GWAS: A review. _Plant

Methods_ 9, 29 (2013). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Su, J. _et al_. Identification of favorable SNP alleles and candidate genes for traits related to early

maturity via GWAS in upland cotton. _BMC Genomics_ 17, 687 (2016). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Vidal, R. O. _et al_. A hight-throughput data minning of single

nucleotide polymorphism in Coffea species expressed sequence tags suggests differential homeologous gene expression in the allotetraploid _Coffea arabica_. _Plant Physiol._ 154, 1053–1066

(2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a

simulation study. _Mol. Ecol._ 14, 2611–2620 (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ivamoto, S. T. _et al_. Transcriptome analysis of leaves, flowers and fruits perisperm of _Coffea

arabica_ L. reveals the differential expression of genes involved in raffinose biosynthesis. _PloS One_ 12, e0169595 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cenci, A.,

Combes, M. C. & Lashermes, P. Genome evolution in diploid and tetraploid Coffea species as revealed by comparative analysis of orthologous genome segments. _Plant Mol. Biol._ L78, 135–45

(2012). Article Google Scholar * Ferrão, L. F. V., Ferrão, R. G., Ferrão, M. A. G., Francisco, A. & Garcia, A. A. F. A mixed model to multiple harvest-location trials applied to

genomic prediction in _Coffea canephora_. _Tree Genet. Genom._ 13, 95 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Labouisse, J. P., Bellachew, B., Kotecha, S. & Bertrand, B. Current status of

coffee (_Coffea arabica_ L.) genetic resources in Ethiopia: implications for conservation. _Genet. Resour. Crop Evol._ 55, 1079–1093 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Jaramillo, J. _et al_.

Some like it hot: The influence and implications of climate change on coffee berry borer (_Hypothenemus hampei_) and coffee production in East Africa. _PLoS One_ 6, e24528 (2011). Article

ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Aerts, R. _et al_. Genetic variation and risks of introgression in the wild _Coffea arabica_ gene pool in south-western Ethiopian mountain

rainforests. _Evol. Appl._ 6, 243–252 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Young, A., Boyle, T. & Brown, T. The population genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation for

plants. _Trends Ecol. Evol._ 11, 413–418 (1996). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Honnay, O., Jacquemyn, H. & Aerts, R. Crop wild relatives: more common ground for breeders and

ecologists. _Front. Ecol. Environ._ 10, 121 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Ellstrand, N. C., Prentice, H. C. & Hancock, J. F. Gene flow and introgression from domesticated plants

into their wild relatives. _Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst._ 30, 539–563 (1999). Article Google Scholar * Hooftman, D. A. P., Jong, M. J. D., Oostermeijer, J. G. B. & Den Nijs, H. J. C. M.

Modelling the long-term consequences of crop-wild relative hybridization: a case study using four generations of hybrids. _J. Appl. Ecol._ 44, 1035–1045 (2007). Article Google Scholar *

Leroy, T. _et al_. Improving the quality of African robustas: QTLs for yield-and quality-related traits in _Coffea canephora_. _Tree Genet. Genom._ 7, 781–798 (2011). Article Google Scholar

* Mérot-L’Anthoëne, V. _et al_. Comparison of three QTL detection models on biochemical, sensory, and yield characters in _Coffea canephora_. _Tree Genet. Genom._ 10, 1541–1553 (2014).

Article Google Scholar * Wang, S. B. _et al_. Improving power and accuracy of genome-wide association studies via a multi-locus mixed linear model methodology. _Sci Rep._ 6, 19444 (2016).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Pereira, L. F. P & Ivamoto, S. T. Chapter 6: Characterization of coffee genes involved in isoprenoid and diterpene metabolic

pathways. In: _Coffee in Health and Disease Prevention_ (Preedy, R. V. Ed.). London: Academic Press, 45-51 (2015). * Branham, S. E., Wright, S. J., Reba, A., Morrison, G. D. & Linder, C.

R. Genome-wide association study in _Arabidopsis thaliana_ of natural variation in seed oil melting point: a widespread adaptive trait in plants. _J. Hered._ 107, 257–265 (2016). Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Li, H. _et al_. Genome-wide association study dissects the genetic architecture of oil biosynthesis in maize kernels. _Nat. Genet._ 45, 43–50

(2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gacek, K. _et al_. Genome-wide association study of genetic control of seed fatty acid biosynthesis in _Brassica napus_. _Front. Plant Sci._

7, 2062 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Yamamura, Y., Kurosaki, F. & Lee, J. B. Elucidation of terpenoid metabolism in _Scoparia dulcis_ by RNA-seq analysis.

_Sci. Rep._ 7, 43311 (2017). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nelson, D. & Werck-Reichhart, D. A P450-centric view of plant evolution. _Plant J._ 66, 194–211

(2011). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ivamoto, S. T., Domingues, D. S., Vieira, L. G. E. & Pereira, L. F. P. Identification of the transcriptionally active cytochrome P450

repertoire in _Coffea arabica_. _Gen. Mol. Res._ 14, 2399–2412 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Li, H. _et al_. Cytochrome P450 family member CYP704B2 catalyzes the ω-hydroxylation of

fatty acids and is required for anther cutin biosynthesis and pollen exine formation in rice. _Plant Cell_ 22, 173–190 (2010). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Syrén,

P. O., Henche, S., Eichler, A., Nestl, B. M. & Hauer, B. Squalene-hopene cyclases-evolution, dynamics and catalytic scope. _Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol._ 41, 73–82 (2016). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Fu, W. _et al_. _Acyl-CoA_ N-acyltransferase influences fertility by regulating lipid metabolism and jasmonic acid biogenesis in cotton. _Sci. Rep._ 5, 11790 (2015).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Qu, C. _et al_. Genome-wide association mapping and Identification of candidate genes for fatty acid composition in _Brassica napus_

L. using SNP markers. _BMC genomics_ 18, 232 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Xu, M. _et al_. Genetic evidence for natural product‐mediated plant–plant allelopathy

in rice (_Oryza sativa_). _New Phytol._ 193, 570–575 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shimura, K. _et al_. Identification of a biosynthetic gene cluster in rice for

momilactones. _J. Biol. Chem._ 282, 34013–34018 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Cunningham, L., Georgellis, D., Green, J. & Guest, J. R. Co-regulation of lipoamide

dehydrogenase and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase synthesis in _Escherichia coli_: characterisation of an ArcA binding site in the lpd promoter. _FEMS Microbiol. Lett._ 169, 403–408 (1998).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, M. & Thelen, J. J. The essential role of plastidial triose phosphate isomerase in the integration of seed reserve mobilization and seedling

establishment. _Plant Signal. Behav._ 5, 583–585 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, M. & Thelen, J. J. The plastid isoform of triose phosphate isomerase is required

for the postgerminative transition from heterotrophic to autotrophic growth in Arabidopsis. _Plant Cell_ 22, 77–90 (2010). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhou, S., Lou,

Y. R., Tzin, V. & Jander, G. Alteration of plant primary metabolism in response to insect herbivory. _Plant Physiol._ 169, 1488–1498 (2015). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

* Cunniff, P. Association of official analytical chemists. _Official Methods of AOAC Analysis_ (1995). * Healey, A., Furtado, A., Cooper, T. & Henry, R. J. Protocol: a simple method for

extracting next-generation sequencing quality genomic DNA from recalcitrant plant species. _Plant Methods_ 10, 21 (2014). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Elshire, R. J.

_et al_. A robust, simple genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) approach for high diversity species. _PLoS One_ 6, e1937910 (2011). Article Google Scholar * Glaubitz, J. C. _et al_. TASSEL-GBS: A

high capacity Genotyping-by-Sequencing analysis pipeline. _PLoS One_ 9, e90346 (2014). Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Peakall, R. & Smouse, P. E. GenAlEx 6.5:

genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research-an update. _Bioinformatics_ 28, 2537–2539 (2012). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. _Genetics_ 155, 945–959 (2000). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Earl, D. A. & von Holdt, B. M. Structure harvester: A website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. _Conserv. Genet. Resour._ 4,

359–361 (2012). Article Google Scholar * Mangin, B. _et al_. Novel measures of linkage disequilibrium that correct the bias due to population structure and relatedness. _Heredity_ 108,

285–291 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bradbury, P. J. _et al_. TASSEL: Software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. _Bioinformatics_ 23, 2633–263

(2007). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wen, Y. J. _et al_. Methodological implementation of mixed linear models in multi-locus genome-wide association studies. _Brief_. _Bioinform_.

BBW145, https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbw145(2017). * Tamba, C. L., Ni, Y. L. & Zhang, Y. M. Iterative sure independence screening EM-Bayesian LASSO algorithm for multi-locus genome-wide

association studies. _PLoS Comput. Biol._ 13, e1005357 (2017). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhang, J. _et al_. pLARmEB: integration of least angle regression with

empirical Bayes for multilocus genome-wide association studies. _Heredity_ 118, 517–524 (2017). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sturn, A., Quackenbush, J. &

Trajanoski, Z. Genesis: cluster analysis of microarray data. _Bioinformatics_ 18, 207–208 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Foll, M. & Gaggiotti, O. A. genome-scan method

to identify selected loci appropriate for both dominant and codominant markers: a Bayesian perspective. _Genetics_ 180, 2977–2993 (2008). Article Google Scholar Download references

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The project is supported by CAPES-Agropolis Foundation under the reference ID 1203–001 through the “Investissements d’avenir” program (Labex Agro: ANR-10-LABX-0001–01); and

the CAPES 015/13 and “Ciência sem Fronteiras” grant (CAPES PVE 084/13). We especially thank the Brazilian Coffee Research Consortium, INCT Café for supporting this study. GCS and STI

acknowledge the Brazilian Coffee Research Consortium and FAPESP for student fellowships. LFPP acknowledges EMBRAPA and CIRAD for the Visiting Scientist Program. LP, DSD and LFPP acknowledge

CNPq for the research fellowship. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Instituto Agronômico do Paraná, Laboratório de Biotecnologia Vegetal, 86047902, Londrina, PR, Brazil Gustavo

C. Sant’Ana, Luiz F. P. Pereira, Suzana T. Ivamoto, Rafaelle V. Ferreira, Natalia F. Pagiatto, Bruna S. R. da Silva, Lívia M. Nogueira, Cintia S. G. Kitzberger, Maria B. S. Scholz, Fernanda

F. de Oliveira & Gustavo H. Sera * CIRAD, UMR AGAP, F-34398, Montpellier, France Gustavo C. Sant’Ana, David Pot, Jean-Pierre Labouisse, Pierre Charmetant & Thierry Leroy * Empresa

Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária, 70770901, Brasília, DF, Brazil Gustavo C. Sant’Ana, Luiz F. P. Pereira & Lilian Padilha * Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto de Biociências,

13506900, Rio Claro, SP, Brazil Suzana T. Ivamoto & Douglas S. Domingues * IRD, CIRAD, Univ. Montpellier, IPME, BP 64501, 34394, Montpellier, France Romain Guyot * AGAP, Univ.

Montpellier, CIRAD, INRA, Montpellier SupAgro, Montpellier, France Gustavo C. Sant’Ana, David Pot, Jean-Pierre Labouisse, Pierre Charmetant & Thierry Leroy Authors * Gustavo C. Sant’Ana

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Luiz F. P. Pereira View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

* David Pot View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Suzana T. Ivamoto View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Douglas S. Domingues View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Rafaelle V. Ferreira View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Natalia F. Pagiatto View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Bruna S. R. da Silva View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lívia M. Nogueira View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Cintia S.

G. Kitzberger View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Maria B. S. Scholz View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Fernanda F. de Oliveira View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Gustavo H. Sera View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lilian Padilha View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jean-Pierre Labouisse View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Romain Guyot View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Pierre Charmetant View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Thierry Leroy View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

CONTRIBUTIONS G.C.S., L.F.P.P., D.P. and T.L.: conceived and designed the study. G.C.S.: performed bioinformatics and statistical analyses. N.P., C.S.K. and M.B.S.S.: performed the

biochemical analysis. R.V.F. and L.M.N., B.S.R.S., F.F.O.: collected plant material and/or extracted DNA. G.S. and P.C.: selected coffee plants in the field. G.C.S., L.F.P.P., D.P., S.T.I.,

L.P., D.S.D., J.P.L. and T.L.: wrote, edited and revised the final manuscript. L.F.P.P., R.G. and T.L.: leaded the project and revised the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Luiz F. P. Pereira. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare that they have no competing interests. ADDITIONAL

INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation,

distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and

indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to

the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will

need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

CITE THIS ARTICLE Sant’Ana, G.C., Pereira, L.F.P., Pot, D. _et al._ Genome-wide association study reveals candidate genes influencing lipids and diterpenes contents in _Coffea arabica_ L.

_Sci Rep_ 8, 465 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18800-1 Download citation * Received: 28 July 2017 * Accepted: 15 December 2017 * Published: 11 January 2018 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18800-1 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(584x439:586x441)/amanda-calo-553b00acd15946829c461184e9241390.jpg)