- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT While heart transplantation (HTX) is the definitive therapy of heart failure, donor shortage is emerging. Pharmacological activation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) and increased

cGMP-signalling have been reported to have cardioprotective properties. Gemfibrozil has recently been shown to exert sGC activating effects _in vitro_. We aimed to investigate whether

pharmacological preconditioning of donor hearts with gemfibrozil could protect against ischemia/reperfusion injury and preserve myocardial function in a heterotopic rat HTX model. Donor

Lewis rats received p.o. gemfibrozil (150 mg/kg body weight) or vehicle for 2 days. The hearts were explanted, stored for 1 h in cold preservation solution, and heterotopically transplanted.

1 h after starting reperfusion, left ventricular (LV) pressure-volume relations and coronary blood flow (CBF) were assessed to evaluate early post-transplant graft function. After 1 h

reperfusion, LV contractility, active relaxation and CBF were significantly (p < 0.05) improved in the gemfibrozil pretreated hearts compared to that of controls. Additionally,

gemfibrozil treatment reduced nitro-oxidative stress and apoptosis, and improved cGMP-signalling in HTX. Pharmacological preconditioning with gemfibrozil reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury

and preserves graft function in a rat HTX model, which could be the consequence of enhanced myocardial cGMP-signalling. Gemfibrozil might represent a useful tool for cardioprotection in the

clinical setting of HTX surgery soon. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS VERBASCOSIDE ATTENUATES MYOCARDIAL ISCHEMIA/REPERFUSION-INDUCED FERROPTOSIS FOLLOWING HETEROTOPIC HEART

TRANSPLANTATION VIA MODULATING GDF15/GPX4/SLC7A11 PATHWAY Article Open access 05 May 2025 EFFECTS OF KETONE BODY 3-HYDROXYBUTYRATE ON CARDIAC AND MITOCHONDRIAL FUNCTION DURING DONATION AFTER

CIRCULATORY DEATH HEART TRANSPLANTATION Article Open access 08 January 2024 TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS OF CELL THERAPY FOR HEART FAILURE: AN UPDATE ON ONGOING TRIALS Article 15 November 2024

INTRODUCTION Although there is a rapid evolution of mechanical circulatory support, heart transplantation (HTX) is still the gold standard definitive therapy of end-stage heart failure.

Ischemia/reperfusion injury is one of the major determinants of primary graft failure and long-term outcome in HTX1. Possible prevention of such an injury can be achieved by a professional

transplant team with efficient logistics, developing surgical techniques and novel cardioplegic solutions2. On the other hand, pharmacological preconditioning of the donor heart before

explantation is a possible approach to reduce ischemia/reperfusion damage of the graft3. During the reperfusion phase, the myocardium of the implanted graft suffers from biochemical and

metabolic alterations, including generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), intracellular calcium overload, energy depletion and acidosis4. There were several attempts to reduce these

biochemical changes, however the most promising novel therapeutic tools modulate the nitric oxide (NO)/soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC)/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)/protein kinase G

(PKG) pathway5. Under physiological circumstances, NO binds to the haem moiety of sGC, which results in the production of cGMP. Furthermore cGMP activates PKG, that phosphorylates the

important effectors which play key roles in the regulation of vasodilation, inhibition of platelet aggregation and vascular smooth muscle proliferation6. In recent studies, cGMP signalling

has been implicated in cardioprotective mechanisms in different disease conditions7. Increased oxidative stress during ischemia/reperfusion leads to the oxidation of sGC, thereby impairing

its activity and responsiveness to endogenous NO, which mechanism could result in the deterioration of the cGMP signalling cascade7. According to recent experimental data pharmacological

activation of sGC could be a promising tool to prevent myocardial oxidative damage8. Cinaciguat (BAY 58-2667), a member of the novel drug family of sGC activators has been extensively

investigated and shown to reduce ischemia/reperfusion injury in experimental models of myocardial infarction and HTX1,8. In spite of the promising results of the pre-clinical studies, the

clinical development of cinaciguat for the indication of acute decompensated heart failure had to be prematurely terminated due to its hypotensive side effect after acute iv. application9.

Gemfibrozil (GEM) is one of the fibrate drugs, which has been used in the clinical routine for decades for the management of combined dyslipidaemia10. The mechanism of action of this drug is

the activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPARα)11, which is a nuclear receptor responsible for the metabolism of carbohydrates and fats12. Interestingly

Sharina _et al_.13 described an existing side effect of GEM in 2015, i.e. activation of the sGC in an _in vitro_ setup. Although sporadic literature data exist14,15,16, the possible

cardioprotective effects of GEM have been poorly investigated. We aimed at evaluating the potential cardioprotective effects of GEM in a clinically relevant, well established rat model of

HTX3,17. RESULTS EFFECT OF GEMFIBROZIL TREATMENT ON ROUTINE BIOCHEMICAL LABORATORY PARAMETERS AND HEMODYNAMIC INDICES OF DONOR RATS Gemfibrozil in a dose of 150 mg/kg body weight had no

significant (p < 0.05) side effect on the kidney and liver parameters in our non-transplanted rats, whereas the total, HDL and LDL cholesterol were significantly (p < 0.05) decreased

(Table 1). Trigliceride plasma level was also elevated in the Gem-nHTX group. Cardiac performance in both systole and diastole, as well as mean arterial pressure of the gemfibrozil and

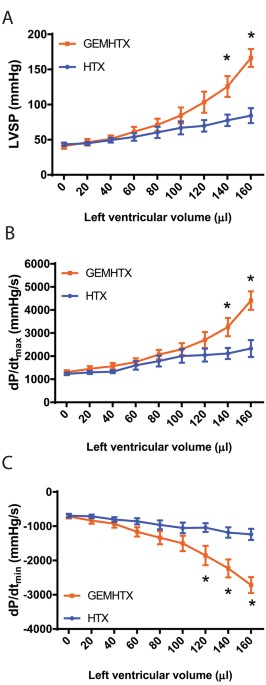

vehicle-treated donor animals were comparable (Table 2). HEMODYNAMIC PARAMETERS AND CORONARY VASCULAR FUNCTION IN THE GRAFT After transplantation, increasing LV balloon volumes (‘preload’)

resulted in elevated LVSP and dP/dtmax, which were both found to be significantly increased at the largest preload volumes used in GEM-HTX compared to HTX (Fig. 1A,B). Moreover, gemfibrozil

treatment led to a similar improvement in diastolic function at higher preload volumes, resulting in significantly (p < 0.05) increased dP/dtmin values compared to HTX, reflecting better

myocardial relaxation (Fig. 1C). Coronary blood flow was also significantly (p < 0.05) increased after 1 h of reperfusion in GEM-HTX compared to the HTX group (Fig. 2), confirming

significantly better coronary endothelial function in our GEM-HTX animals. MYOCARDIAL GENE EXPRESSION Quantitative RT-PCR from myocardial RNA extracts revealed that relative mRNA-expression

for protooncogene c-fos was significantly upregulated in the gemfibrozil and vehicle-treated transplant group (Fig. 3A). eNOS myocardial mRNA expression was significantly elevated in the

GEM-HTX group (Fig. 3B). Pharmacological preconditioning with GEM resulted in a significant increase of the mRNA expression for cytochrome C and for the antioxidant enzyme SOD2 (Fig. 3C,D).

MYOCARDIAL PROTEIN EXPRESSION Protein expression of sGC β1 was significantly reduced in the vehicle-treated transplant group whereas gemfibrozil treatment restored the enzyme’s protein level

near to physiological values (Fig. 4A). We detected elevated cleaved caspase-3 protein expression in the control transplant group, whereas the application of gemfibrozil significantly

reduced the expression of cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 4B). HISTOPATHOLOGY The HTX group was associated with increased 3-NT immunoreactivity in LV myocardium referring to pronounced

nitro-oxidative stress, which was significantly (p < 0.05) prevented by gemfibrozil (Fig. 5A,B). The number of TUNEL-positive nuclei was significantly (p < 0.05) increased in the

myocardium after transplantation referring to pronounced DNA fragmentation (Fig. 5C), GEM succesfully reduced the ischemia/reperfusion injury-induced DNA-strand breaks in HTX represented by

markedly reduced TUNEL positivity (Fig. 5C). MYOCARDIAL AND PLASMA CGMP LEVELS IN THE DONORS Semiquantitative analysis of myocardial cGMP levels has shown that there was significantly (p

< 0.05) more cGMP in the myocardium of GEM-HTX animals than in the other groups (Fig. 5D,E). Similarly, gemfibrozil preconditioning activated sGC and thus increased the plasma cGMP levels

in GEM-nHTX (Fig. 5F). The increased cGMP level does not seem to be the consequence of a difference in NO production in these animals, as total nitrate/nitrite concentration of urine

samples were not different (Fig. 6). PLATELET ACTIVATION AND RECRUITMENT OF LEUKOCYTES IN THE MYOCARDIUM Essentially no platelets or neutrophils were detected in the myocardial tissue of the

non-transplanted groups (Fig. 7A). After 1 hour of cold ischemic time and reperfusion, increased myocardial P-selectin immunoreactivity was detected reflecting platelet activation and

leukocyte recruitment in the vasculature of previously ischemic myocardium (Fig. 7A,B). However, GEM treatment prevented the increase of P-selectin immunoreactivity in the myocardium after

transplantation (Fig. 7B). DISCUSSION Our present study is the first to investigate the effect of gemfibrozil on global myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in an _in vivo_ model of

heterotopic rat HTX. Our results show that preconditioning of the donor heart with gemfibrozil improves post-transplant systolic and diastolic LV function and increases CBF by attenuating

ischemia/reperfusion injury of the myocardium. The gold standard therapy of terminal heart failure is HTX, however the need for donors is constantly increasing18. Due to the long ischemic

time of the donor heart, the chance of primary graft failure is higher in the early post-operative period. As part of the ischemia/reperfusion injury-related inflammatory response, activated

neutrophils release a variety of cytotoxic substances such as ROS and proteases. Moreover, they activate monocytes/macrophages that are the main source of inflammatory cytokines in the

ischemic heart. Inflammatory cytokines released from activated leukocytes directly mediate vascular endothelial dysfunction with subsequent myocardial injury and the deterioration of NO-cGMP

signalling. Additionally, after a long ischemic transport time, the level of ROS massively increases during reperfusion and the increased superoxide production scavenges the small amount of

remaining NO contributing significantly to the decreased NO bioavailability. The NO-sGC-cGMP-PKG pathway has important physiological role in the regulation of cardiac function including

coronary vasodilation, inhibition of inflammatory pathways, attenuation of oxidative stress and in the modulation of cardiac contractility19,20. Recent literature data suggest that

restoration of cGMP-PKG signalling has potential cardioprotective effects in various cardiac diseases14,15,16 including HTX-associated ischemia/reperfusion injury1. Oxidative stress triggers

a decrease in sGC expression and activity21. Furthermore, oxidative stress is associated with increased expression and activity of PDE-522 which leads to the imbalance in cGMP synthesis and

degradation. This results in lower cGMP-levels and thus in impaired regulation of cGMP-PKG signalling pathway23. However, a novel class of drugs, the sGC activators might overcome this

issue by preserving the structure, function and activity of sGC in nitro-oxidative stress23. Although sGC activation is a promising way to go, these compounds have not been approved for

clinical use yet. The widely used fibrate gemfibrozil has been recently described as a NO- and haem-independent activator of sGC13. Sharina _et al_. suggested that the mechanism of action of

gemfibrozil was similar to haem-mimicking sGC-activators, however it was less potent than cinaciguat or ataciguat13. The advantage of gemfibrozil is that it has been approved for decades

and used in the pharmacological management of hyperlipidemia13. According to the above findings, we have observed significantly reduced protein level of sGC in the HTX group which might

reflect to the increased rate of degradation of the enzyme. Gemfibrozil treatment, however, prevented the degradation of sGC that might have resulted in preserved function of sGC in our

model. Furthermore, pharmacological preconditioning with gemfibrozil was associated not only with signficantly increased plasma cGMP levels in the donor but also it increased myocardial cGMP

level after HTX without affecting NO production in our animals. This phenomenon might play a key role in the reduction of ischemia/reperfusion injury of the graft. Another possible

explanation for the above observed effects is that the sGC-activator gemfibrozil might improve the synthesis of different antioxidant proteins via PKG-mediated processes24. These events

could notably contribute to vaso- and cardioprotection in oxidative injury. Oxidative and nitrosative stress lead to the formation of peroxynitrite which is a highly reactive molecule that

can disrupt enzymes and other proteins25. Peroxynitrite can also uncouple eNOS that becomes a dysfunctional superoxide-generating enzyme contributing to enhanced oxidative stress26. The

myocardial antioxidant enzyme SOD2 plays a major role in the elimination of ischemia/repefusion-induced elevation of ROS27. In accordance with this, we observed significantly elevated 3-NT

staining in HTX, reflecting increased nitro-oxidative stress. However, SOD2 mRNA expression increased in the gemfibrozil treated groups, which process might have contributed to the

antioxidant effects of the drug. Additionally, the sGC-derived cGMP activates PKG that in turn leads to the opening of the mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels28 and to increased

potassium-influx into the mitochondrion. This mechanism enables protons to be pumped out for the formation of H+ eletrochemical gradient and thereby it increases mitochondrial

ATP-synthesis29. The above mechanism might have played a role in the cardioprotective effects of sGC activation by gemfibrozil by the preservation of ATP-synthesis in ischemia/reperfusion

injury. Moreover, myocardial cytochrome-c (terminal member of the mitochondrial electron transport chain) was upregulated in the gemfibrozil-treated transplanted group which might indicate

that gemfibrozil enhances mitochondrial ATP-production. As a result of increased nitro-oxidative stress and the disturbed myocardial energy balance (including ATP depletion) after

ischemia/reperfusion, myocardial cell apoptosis and necrosis may occur30. In accordance with this, the modulation of the ATP degradation pathways at different levels is an important strategy

to reduce tissue injury in ischemia/reperfusion31. Additionally, c-fos, a transcription factor of the activator protein-1 family has been linked to apoptosis32. Furthermore, caspase 3 has a

central role in the execution phase of cell death as it is responsible for chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation26. Agosto M. et colleagues described that in ST-segment elevation

myocardial infarction (STEMI) the severity of the myocardial injury was correlated with the caspase 3 (p17 fragment) serum level33. Our findings are in concordance with the above data, since

we observed increased number of TUNEL positive cardiomyocyte nuclei (marker of increased DNA fragmentation), significantly elevated level of cleaved caspase 3 (marker of caspase 3

activation) and the overexpression of c-fos transcription factor in HTX. The sGC activator gemfibrozil, however, has been shown to have anti-apoptotic properties in the donor heart by

reducing TUNEL positivity and caspase 3 activation. Interestingly, gemfibrozil had no effect on c-fos mRNA level which might have been a result of the relative short reperfusion phase.

Heterotopic HTX was used in our study to simulate the clinical conditions of HTX with whole blood reperfusion. This method allows an observation time of 60 minutes. Based on literature data,

we determined the reperfusion time to 1 h, where the ischemia/reperfusion injury is the most pronounced with subsequent functional deterioration of the graft17. Although heterotopically

transplanted hearts in our model beat in an unloaded fashion (no preload), cardiac pump function can be reliably assessed with the help of a ballon catheter inserted into the LV of the

graft. Both systolic and diastolic performance of the LV can be investigated by registering LVSP, dP/dtmax, and dP/dtmin, respectively, at different LV (balloon) volumes. The increased slope

of the relations between these parameters and LV volume demonstrate preserved systolic (contractility) and diastolic function (active relaxation) in the GEM-HTX group when compared to

controls. Moreover, GEM treatment resulted in significant improvement of CBF in the treated-HTX group which might reflect the vasoprotective properties of the drug. We hypothesize that the

activation of sGC34 by gemfibrozil and the subsequently enhanced cGMP-PKG signalling promotes multiple phosphorylation of intracellular targets, reduce endothelial injury35 and can lower the

cellular Ca2+-concentrations that might contribute to vasodilation and vasoprotection36. This vasodilatative effect of gemfibrozil could be responsible for the elevated CBF and might lead

to a rapid recovery of the stunned myocardium during reperfusion. Additionally, it has been described that GEM succesfully reduced the incidence of cardiac allograft vasculopathy after HTX

in adults by lowering endothelial damage37. Moreover, sGC activation and the possible eNOS reactivation in the coronaries (indicated by increased eNOS mRNA expression) and NO production

might contributed synergistically to the decreased amount of nitro-oxidative stress in our model. Consequently, we observed improved systolic and diastolic function of the graft after HTX.

In accordance with previous works with other sGC-activators1 we found that GEM did not affect cardiac function of healthy control rats. Thus, the improved cardiac function seen in the

GEM-HTX group is a specific phenomenon, reflecting a protection against the ischemia/reperfusion-associated impairment of myocardial performance, rather than the consequence of some

non-specific direct cardiac effects of GEM. Although fibrates are described to have potential harmful side effects38, our biochemical results showed no signs of liver, kidney or muscle

damage in the GEM treated healthy rats. Thus, gemfibrozil could become a safe and useful tool for the management of cardiac donors without having substantial side effects on other organs.

Microvascular obstruction is considered to be one of the major manifestations of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and is associated with enhanced leukocyte invasion39. P-selectin, a

transmembrane adhesion molecule (glycoprotein), is constitutively stored in granules of endothelial cells and platelets but becomes exposed under pathological circumstances40. P-selectin

plays a pivotal role during ischemia-reperfusion injury by enhancing leukocyte invasion. Indeed, a previous study found that blockade of P-selectin protected against acute renal failure

following ischemia-reperfusion injury41. In line with these findings, here we document a significantly higher myocardial P-selectin immunoreactivity in non-treated grafts. However,

gemfibrozil pretreatment was associated with a P-selectin level that was comparable to that of control hearts (i.e. non-transplant groups, which did not suffer global cardiac

ischemia/reperfusion injury). This may highlight the potent anti-inflammatory effect of the sGC activator gemfibrozil, which could substantially contribute to the cardioprotective effect of

the drug in the setting of ischemia/reperfusion injury. Our study have several limitations. First the donor rat hearts are implanted to recipients with ‘healthy’ circulatory system. In that

case, the CBF of the graft becomes elevated thus it might partly be responsible for the improved myocardial protection after ischemia/reperfusion injury. Besides, ischemia/reperfusion injury

is a reversible phenomenon in this model and it allows a fast recovery, making it difficult to find differences between experimental groups after a certain time of reperfusion.

Additionally, the dose of administration of gemfibrozil might be different in a clinical setup due to the differences of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties in rats and in humans.

To conclude, gemfibrozil treatment improves donor heart function in an experimental model of HTX. The potential sGC activator properties of gemfibrozil might be in the background of its

cardioprotective effects. These findings show that pharmacological preconditioning with gemfibrozil could be a promising option to reduce ischemia/reperfusion injury and to increase the

ischemic time in order to gain enough donor organs for cardiac transplantation. METHODS ANIMALS Male Lewis rats (250–350 g; Charles River, Germany) were housed in a room at 22 ± 2 °C under

12-h light/dark cycles and were fed a standard laboratory rat diet and water _ad libitum_. The rats were acclimatized for at least 1 week before experiments. All animals received humane care

in compliance with the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” formulated by the National Society for Medical Research and the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” prepared by

the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources and used by the National Institutes of Health (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the US National Institutes of

Health [Eighth Edition] the National Academy Press. 2011 and directive 2010/63/EU of the European parliament and of the council on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.

Official Journal of the European Union. 2010). All procedures and handling of the animals during the study were reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of Hungary for Animal

Experimentation. EXPERIMENTAL GROUPS Rats were randomly divided into four groups: (1) control-group (nHTX, n = 8): donor rats received methylcellulose vehicle and hearts were not

transplanted (2) gemfibrozil-control group (GEM-nHTX, n = 8): donor rats received gemfibrozil and hearts were not transplanted (3) transplant-control group (HTX): donor rats (n = 8) received

methylcellulose vehicle, then hearts were transplanted into the recipients (n = 8) and (4) gemfibrozil + transplant-group (GEM-HTX): donor rats (n = 8) received gemfibrozil, then hearts

were transplanted into the recipients (n = 8). Donor rats were preoperatively treated orally with vehicle or gemfibrozil while recipient rats received no treatment. DRUG APPLICATION GEM was

purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany), suspended in 1% methylcellulose solution vehicle and administered via oral gavage at the dose of 150 mg/kg body weight (BW). The

application started two days before explantation twice a day (8:00 AM and 08:00 PM) and one dose an hour before the procedure. This dose and administration method have been determined

according to the pharmacokinetic and –dynamic properties42 of gemfibrozil as well as to the results of previous rodent and human experiments13,43,44. RAT MODEL OF HEART TRANSPLANTATION Rat

model of heart transplantation was performed as described previously17,45. Transplantations were performed in isogenic Lewis to Lewis rats in order to avoid possible organ rejection.

Briefly, the donor rats were anaesthetized with isoflurane and heparinized (25000 IU iv). A bilateral thoracotomy was performed to expose the heart. After cardiac arrest the superior and

inferior caval veins and the pulmonary veins were tied en masse with a suture and the heart was excised with the aortic arch for future measurement of the coronary blood flow (CBF). After

excision hearts were stored in cold cardioplegic solution (Custodiol, 4 °C, Dr. Franz Köhler Chemie GmbH, Bensheim, Germany). The recipient rats were anaesthetized with isoflurane and then

heparinized (400 IU/kg iv) and the body temperature was maintained at 37 °C on a heating pad. Approximately two-centimeter segments of the infrarenal aorta and the caval vein were isolated

and occluded by small-vessel forceps. The aorta and the pulmonary artery of the donor heart were anastomosed end to side to the abdominal aorta and the vena cava of the recipient rat,

respectively. The duration of the implantation was standardized at 1 h (ischemic period) to minimize variability between experiments. After the completion of the anastomoses, heparin was

antagonized with protamin (400 IU/kg iv.) and the occlusion was released and the heart was then reperfused with blood _in situ_ for 60 minutes. BIOCHEMICAL MEASUREMENTS After hemodynamic

measurements of the non-transplanted groups, blood samples were collected from the inferior vena cava in tubes pre-rinsed with EDTA. Plasma albumine, alkaline phosphatase, glutamate-pyruvate

transaminase (GPT), glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase (GOT), high and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL, LDL), total cholesterol, triglyceride, direct and total bilirubine,

carbamide, creatinine, creatine kinase (CK) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were measured by automated clinical laboratory assays on a Cobas Integra 400 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim,

Germany) autoanalyzer. Plasma cGMP levels were determined from the non-transplanted groups by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) using a commercial kit (Amersham cGMP EIA Biotrak System, GE

Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). Total nitrate/nitrite concentration (a marker of whole body NO production) was measured from urine samples using a colorimetric kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann

Arbor, MI, USA). We followed the protocols supplied by the producers. FUNCTIONAL MEASUREMENTS IN THE DONOR We compared the effect of the treatment on the hemodynamic parameters of the donor

heart before explantation as follows. Invasive hemodynamic measurements were carried out with a 2F microtip pressure-conductance microcatheter (SPR-838, Millar Instruments, Houston, TX, USA)

with modifications as described previously46,47. Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (1–2%). Rats were placed on heating pads to maintain core temperature at 37 °C. The left external

jugular vein was cannulated with a polyethylene catheter for fluid administration. Firstly, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) were recorded. Thereafter, the catheter was

advanced into the left ventricle (LV) under pressure control. Signals were recorded at a sampling rate of 1000 samples/s using a pressure-volume (P-V) conductance system (MPVS-Ultra, Millar

Instruments) and the PowerLab 16/30 data acquisition system (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). We used a special P-V analysis programme (PVAN, Millar Instruments) to calculate

mean arterial pressure (MAP), maximal LV end-systolic pressure, LV end-diastolic pressure, maximal slope of systolic pressure increment (dP/dtmax) and diastolic pressure decrement

(dP/dtmin). FUNCTIONAL MEASUREMENTS IN THE GRAFT One hour after transplantation a 3F latex balloon catheter (Edwards Lifesciences Corporation, Irvine, CA, USA) was introduced into the left

ventricle via the apex to determine maximal left ventricular (LV) systolic pressure (LVSP), maximal slope of the systolic pressure increment (dP/dtmax) and diastolic pressure decrement

(dP/dtmin) and heart rate (HR) by a Millar micromanometer (SPR-838, Millar Instruments) at different LV volumes (20–160 µl). From these data LV pressure-volume relationships were

constructed. Coronary blood flow (CBF) of the graft was measured by an ultrasonic flow meter (Transonic Systems Inc., Ithaca,USA) mounted on the donor ascending aorta. QUANTITATIVE REAL-TIME

POLYMERASE CHAIN-REACTION (PCR) Frozen LV samples were homogenized, total RNA was isolated as described previously46. Reverse transcription was performed and cDNA samples were amplified on

the StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using TaqMan® Universal PCR MasterMix and TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) for the

following targets: c-fos (Rn02396759_m1) a transcription factor, cytochrome-c (Rn00470541_g1) a terminal member of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, members of different

antioxidant systems like superoxide dismutase (SOD-2; Rn00690587_g1), and the endothelial nitrite oxide synthase (eNOS; Rn02132634_s1). Gene expression data were normalized to Ribosomal

Protein L27 (RPL27; rn00821099_g1) as housekeeping gene. The mRNA expression levels were calculated using the CT comparative method (2−ΔCT) and adjusted to a pool of nHTX group. WESTERN BLOT

ANALYSIS LV tissue samples were homogenized, protein concentration was determined as described previously46 and equal amounts of protein were separated via gel-electrophoresis. Proteins

were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking, membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against sGC (1:1000 SAB4501344, Sigma-Aldrich, Budapest, Hungary) and caspase-3

(1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA #9662,). After washing, membranes were incubated in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Immunoblots were developed by enhanced

chemiluminescence detection. Protein band densities were quantified using GeneTools software (Syngene, Frederick, MD, USA). We have adjusted the protein band densities to α-tubulin (1:10000,

sigma T5168, Sigma-Aldrich, Budapest, Hungary). HISTOLOGY, IMMUNHISTOCHEMISTRY Hearts were fixed in buffered paraformaldehyde solution (4%), embedded in paraffin and 5-μm thick sections

were cut. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) reaction was performed (DeadEnd™ Colorimetric TUNEL System, Promega, Mannheim, Germany) to detect DNA

strand breaks. The nitro-oxidative stress marker 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) (#10189540, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was detected by immunohistochemical staining as previously

described46 and 3-NT positive area was analyzed with Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) software. For identification of intracellular cGMP (#ab12416, Abcam, Cambridge, UK),

immunohistochemistry was performed according to a previously described method46. In case of P-selectin staining, paraffin-embedded sections (5 μm) were rehydrated and incubated with 1%

hydrogen peroxide. After being rinsed in PBS, the sections were incubated with blocking serum. Immunostaining was performed with the use of a mouse polyclonal antibody (Impress Reagent,

Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK)48. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Normal distribution was tested by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In case of normal distribution,

one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test were performed. Where data showed not normal distribution Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA and Dunn’s post hoc test were done. In case of hemodynamic data in

HTX two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test was used. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. REFERENCES * Loganathan, S. _et al_. Effects of soluble guanylate cyclase

activation on heart transplantation in a rat model. _J Heart Lung Transplant_ 34, 1346–1353, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2015.05.006 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Li, S.

_et al_. Short- and long-term effects of brain death on post-transplant graft function in a rodent model. _Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg_ 20, 379–386, https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivu403

(2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Benke, K. _et al_. Heterotopic Abdominal Rat Heart Transplantation as a Model to Investigate Volume Dependency of Myocardial Remodeling.

_Transplantation_, https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000001585 (2016). * Hearse, D. J. & Bolli, R. Reperfusion induced injury: manifestations, mechanisms, and clinical relevance.

_Cardiovasc Res_ 26, 101–108 (1992). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Szabo, G. _et al_. Vardenafil protects against myocardial and endothelial injuries after cardiopulmonary bypass.

_European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery_ 36, 657–664, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.03.065 (2009).

Article Google Scholar * Lincoln, T. M. Cyclic GMP and mechanisms of vasodilation. _Pharmacol Ther_ 41, 479–502 (1989). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bice, J. S., Burley, D. S.

& Baxter, G. F. Novel approaches and opportunities for cardioprotective signaling through 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate manipulation. _J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther_ 19, 269–282,

https://doi.org/10.1177/1074248413518971 (2014). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Korkmaz, S. _et al_. Pharmacological activation of soluble guanylate cyclase protects the heart

against ischemic injury. _Circulation_ 120, 677–686, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.870774 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Erdmann, E. _et al_. Cinaciguat, a

soluble guanylate cyclase activator, unloads the heart but also causes hypotension in acute decompensated heart failure. _Eur Heart J_ 34, 57–67, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs196

(2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fruchart, J. C. & Duriez, P. Mode of action of fibrates in the regulation of triglyceride and HDL-cholesterol metabolism. _Drugs Today

(Barc)_ 42, 39–64, https://doi.org/10.1358/dot.2006.42.1.963528 (2006). CAS Google Scholar * Ferri, N., Corsini, A., Sirtori, C. & Ruscica, M. PPAR-alpha agonists are still on the

rise: an update on clinical and experimental findings. _Expert opinion on investigational drugs_ 26, 593–602, https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2017.1312339 (2017). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Cunningham, M. L. _et al_. Effects of the PPARalpha Agonist and Widely Used Antihyperlipidemic Drug Gemfibrozil on Hepatic Toxicity and Lipid Metabolism. _PPAR Res_ 2010,

https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/681963 (2010). * Sharina, I. G. _et al_. The fibrate gemfibrozil is a NO- and haem-independent activator of soluble guanylyl cyclase: _in vitro_ studies. _Br J

Pharmacol_ 172, 2316–2329, https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13055 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Phelps, L. E. & Peuler, J. D. Evidence of direct smooth

muscle relaxant effects of the fibrate gemfibrozil. _J Smooth Muscle Res_ 46, 125–142 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Singh, A. P., Singh, R. & Krishan, P. Ameliorative role

of gemfibrozil against partial abdominal aortic constriction-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rats. _Cardiol Young_ 25, 725–730, https://doi.org/10.1017/S104795111400081X (2015). Article

PubMed Google Scholar * Calkin, A. C., Cooper, M. E., Jandeleit-Dahm, K. A. & Allen, T. J. Gemfibrozil decreases atherosclerosis in experimental diabetes in association with a

reduction in oxidative stress and inflammation. _Diabetologia_ 49, 766–774, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-0102-6 (2006). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Szabo, G. _et al_.

Poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase inhibition reduces reperfusion injury after heart transplantation. _Circulation research_ 90, 100–106 (2002). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Levy, D. _et

al_. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. _N Engl J Med_ 347, 1397–1402, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020265 (2002). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Ferdinandy, P. & Schulz, R. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite in myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury and preconditioning. _Br J Pharmacol_ 138, 532–543,

https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0705080 (2003). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Nemeth, B. T. _et al_. Cinaciguat prevents the development of pathologic hypertrophy in

a rat model of left ventricular pressure overload. _Sci Rep_ 6, 37166, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37166 (2016). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gerassimou, C.

_et al_. Regulation of the expression of soluble guanylyl cyclase by reactive oxygen species. _Br J Pharmacol_ 150, 1084–1091, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0707179 (2007). Article CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Farrow, K. N. _et al_. Hyperoxia increases phosphodiesterase 5 expression and activity in ovine fetal pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. _Circ

Res_ 102, 226–233, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161463 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Evgenov, O. V. _et al_. NO-independent stimulators and activators of soluble

guanylate cyclase: discovery and therapeutic potential. _Nat Rev Drug Discov_ 5, 755–768, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2038 (2006). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Coletta, C. _et al_. Hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide are mutually dependent in the regulation of angiogenesis and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation. _Proc Natl Acad Sci USA_ 109,

9161–9166, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1202916109 (2012). Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Pacher, P., Beckman, J. S. & Liaudet, L. Nitric oxide and

peroxynitrite in health and disease. _Physiol Rev_ 87, 315–424, https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00029.2006 (2007). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Olah, A. _et al_.

Cardiac effects of acute exhaustive exercise in a rat model. _Int J Cardiol_ 182, 258–266, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.12.045 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Qu, D. _et

al_. Cardioprotective Effects of Astragalin against Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Isolated Rat Heart. _Oxid Med Cell Longev_ 2016, 8194690, https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8194690

(2016). PubMed Google Scholar * Loganathan, S. _et al_. Effects of selective phosphodiesterase-5-inhibition on myocardial contractility and reperfusion injury after heart transplantation.

_Transplantation_ 86, 1414–1418, https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0b013e31818aa34e (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Costa, A. D. _et al_. Protein kinase G transmits the

cardioprotective signal from cytosol to mitochondria. _Circ Res_ 97, 329–336, https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.0000178451.08719.5b (2005). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Eefting, F.

_et al_. Role of apoptosis in reperfusion injury. _Cardiovasc Res_ 61, 414–426, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.023 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Szabo, G. _et

al_. Effects of inosine on reperfusion injury after heart transplantation. _Eur J Cardiothorac Surg_ 30, 96–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.04.003 (2006). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Bossy-Wetzel, E., Bakiri, L. & Yaniv, M. Induction of apoptosis by the transcription factor c-Jun. _EMBO J_ 16, 1695–1709, https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/16.7.1695 (1997).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Agosto, M., Azrin, M., Singh, K., Jaffe, A. S. & Liang, B. T. Serum caspase-3 p17 fragment is elevated in patients with ST-segment

elevation myocardial infarction: a novel observation. _J Am Coll Cardiol_ 57, 220–221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.628 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Denninger, J. W.

& Marletta, M. A. Guanylate cyclase and the NO/cGMP signaling pathway. _Biochim Biophys Acta_ 1411, 334–350 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dawson, T. A. _et al_.

Cardiac cholinergic NO-cGMP signaling following acute myocardial infarction and nNOS gene transfer. _American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology_ 295, H990–H998,

https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00492.2008 (2008). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Surks, H. K. _et al_. Regulation of myosin phosphatase by a specific interaction

with cGMP- dependent protein kinase Ialpha. _Science_ 286, 1583–1587 (1999). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hollis, I. B., Reed, B. N. & Moranville, M. P. Medication management

of cardiac allograft vasculopathy after heart transplantation. _Pharmacotherapy_ 35, 489–501, https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1580 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chang, J. T.,

Staffa, J. A., Parks, M. & Green, L. Rhabdomyolysis with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and gemfibrozil combination therapy. _Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf_ 13, 417–426,

https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.977 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hausenloy, D. J. & Yellon, D. M. Ischaemic conditioning and reperfusion injury. _Nature reviews.

Cardiology_ 13, 193–209, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2016.5 (2016). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * McEver, R. P., Beckstead, J. H., Moore, K. L., Marshall-Carlson, L. &

Bainton, D. F. GMP-140, a platelet alpha-granule membrane protein, is also synthesized by vascular endothelial cells and is localized in Weibel-Palade bodies. _The Journal of clinical

investigation_ 84, 92–99, https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI114175 (1989). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Singbartl, K., Green, S. A. & Ley, K. Blocking P-selectin

protects from ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute renal failure. _FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology_ 14, 48–54 (2000). CAS

Google Scholar * Todd, P. A. & Ward, A. Gemfibrozil. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in dyslipidaemia. _Drugs_ 36, 314–339 (1988).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dix, K. J., Coleman, D. P. & Jeffcoat, A. R. Comparative metabolism and disposition of gemfibrozil in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats and

Syrian golden hamsters. _Drug Metab Dispos_ 27, 138–146 (1999). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Miller, D. B. & Spence, J. D. Clinical pharmacokinetics of fibric acid derivatives

(fibrates). _Clin Pharmacokinet_ 34, 155–162, https://doi.org/10.2165/00003088-199834020-00003 (1998). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hegedus, P. _et al_. Dimethyloxalylglycine

treatment of brain-dead donor rats improves both donor and graft left ventricular function after heart transplantation. _J Heart Lung Transplant_ 35, 99–107,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2015.06.016 (2016). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Matyas, C. _et al_. The soluble guanylate cyclase activator cinaciguat prevents cardiac dysfunction in

a rat model of type-1 diabetes mellitus. _Cardiovasc Diabetol_ 14, 145, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-015-0309-x (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Radovits,

T. _et al_. An altered pattern of myocardial histopathological and molecular changes underlies the different characteristics of type-1 and type-2 diabetic cardiac dysfunction. _J Diabetes

Res_ 2015, 728741, https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/728741 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar * Xu, Y. _et al_. Activated platelets contribute importantly to

myocardial reperfusion injury. _American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology_ 290, H692–699, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00634.2005 (2006). Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Technical assisstance of Tímea Fischinger, Gábor Fritz, Henriett Biró, Dóra Juhász, Edina Urbán, Gabriella Molnár and co-workers of

Central Laboratory of the Heart and Vascular Center is gratefully acknowledged. Advices of Judit Skopál, Sevil Korkmaz-Icöz and Shiliang Li are appreciated. This study was supported by the

National Research, Development and Innovation Office of Hungary (NKFIH; NVKP-16-1-2016-0017, “National Heart Program”), by the “ÚNKP-16-3 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry of

Human Capacities of Hungary” (to K.B.), by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (to T.R.) and by the Human Resource Support Office (National Talent

Program; NTP-NFTÖ-16-0081; to C.M.). AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * Kálmán Benke and Csaba Mátyás contributed equally to this work. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Heart and Vascular Center,

Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary Kálmán Benke, Csaba Mátyás, Alex Ali Sayour, Attila Oláh, Balázs Tamás Németh, Mihály Ruppert, István Hartyánszky, Zoltán Szabolcs, Béla Merkely

& Tamás Radovits * Department of Cardiac Surgery, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany Gábor Szabó * Department of Pathophysiology, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary

Gábor Kökény * Department of Physiology, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary Eszter Mária Horváth Authors * Kálmán Benke View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Csaba Mátyás View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Alex Ali Sayour View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Attila Oláh View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Balázs Tamás Németh View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Mihály Ruppert View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Gábor Szabó View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Gábor Kökény View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Eszter Mária

Horváth View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * István Hartyánszky View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Zoltán Szabolcs View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Béla Merkely View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Tamás Radovits View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS K.B., C.M., B.M. and T.R. conceived the study;

K.B., C.M., A.A.S., A.O., B.T.N., M.R, G.S., G.K., E.M.H., I.H, Z.S., and T.R. conducted experiments; K.B., C.M., A.A.S., and T.R. analysed and interpreted the results. K.B., C.M., A.A.S.

and T.R. edited the manuscript. All listed authors reviewed the manuscript. K.B. and C.M. contributed equally to this study. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Kálmán Benke. ETHICS

DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare that they have no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source,

provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons

license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by

statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Benke, K., Mátyás, C., Sayour, A.A. _et al._ Pharmacological preconditioning with

gemfibrozil preserves cardiac function after heart transplantation. _Sci Rep_ 7, 14232 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14587-3 Download citation * Received: 07 April 2017 *

Accepted: 12 October 2017 * Published: 27 October 2017 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14587-3 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this

content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative