- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

While the theory of imperfections in solids is firmly established, procedures for first-principles calculations of defect quantities continue to evolve. A plethora of ad hoc correction

schemes is being replaced by sophisticated self-consistent procedures that will enable more quantitative predictions of the formation energies of defect species and their spectroscopic

signatures. The formation of defects in crystals is a natural consequence of chemical thermodynamics—the balance between the enthalpic cost of perturbing the atomic bonding environments and

the entropic gain of introducing an ensemble of imperfections. The key quantity that determines, in equilibrium, if a particular defect species will be abundant or rare is the free energy of

formation, Δ_G__f_. The concentration (_n__d_) can be decomposed into contributions from enthalpy and vibrational entropy $${n}_{d}={N}_{{\rm{site}}}g\exp \left(-\frac{{{\Delta

}}{H}_{f}}{{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T}\right)\exp \left(\frac{{{\Delta }}{S}_{f}}{{k}_{{\rm{B}}}}\right),$$ (1) where _N_site and _g_ denote the number and degeneracy of available sites in the host

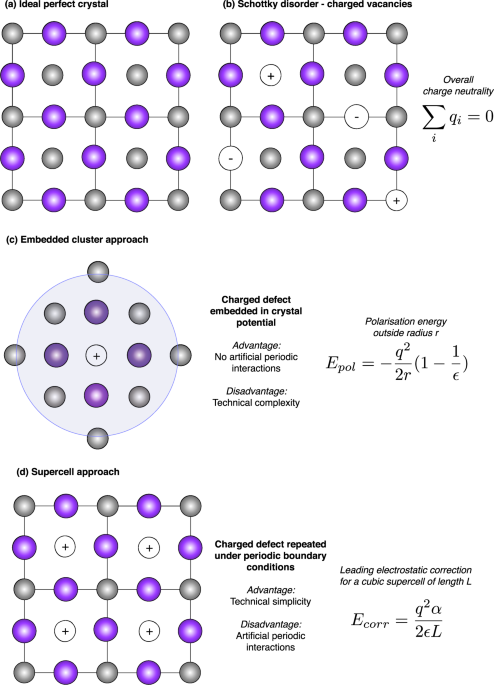

crystal. The enthalpy change dominates under standard conditions, so the more burdensome vibrational term1 is most often neglected. The first objective in defect modelling is to calculate

Δ_H__f_ as accurately as possible, which can be achieved in a number of ways, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Due to the exponential factor in Eq. (1), the prediction of defect concentrations is

sensitive to the quality of the underlying energy terms. My brief perspective on major developments in this field is given below. I apologise in advance to the many contributions that are

overlooked in this synopsis (e.g. see ref. 2 for a more thorough overview). EARLY 20TH CENTURY—THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS The theory of lattice dynamics developed by Born and others described

the motion of atoms around their equilibrium crystallographic positions. However, what if atoms left its ideal position and wandered into an interstitial position? A classical numerical

procedure for calculating the formation energy of such point defects in ionic solids was proposed by Frenkel in 19263. The semi-classical (continuum) Mott–Littleton method for charged

defects energetics was reported in 19384, which was later expanded into a more general framework for multi-region embedded crystal calculations5. The extensive theoretical infrastructure

subsequently developed for describing the electronic structure of donor and acceptor levels in semiconductors was reviewed by Pantelides in 19786. LATE 20TH CENTURY—PRACTICAL SOLUTIONS The

combination of efficient algorithms to solve the Kohn–Sham equations and massively parallel computing enabled the modern era of computational materials science. Two types of approaches were

developed for modelling charged point defects in crystals. Those based on embedding potentials (a dilute defect in a host matrix as shown in Fig. 1c) offer some advantages, but remain

technically challenging to set up and analyse7. A self-consistent Green’s function procedure for treating defect perturbations was already reported in 19798 and quickly adapted to describe

the deep states associated with transition metal impurities in Si using a local density functional9. The alternative, and more widely employed, supercell approach benefits from the robust

infrastructure for calculation of crystals within periodic boundary conditions (Fig. 1d). The principal issue in describing charged defects is the electrostatic interaction between repeating

centres. The long-range Coulomb interaction depends on the defect charge _q_, their spatial arrangement, and the dielectric response of the host _ϵ_(_r_). The standard solution is to

introduce a homogeneous ‘jellium’ background charge to enforce charge neutrality in each repeat unit and ensure convergent Coulomb energy. This fix results in a shift in the average

electrostatic potential and total energy of the defective supercell that must be corrected to become useful (Fig. 2). Leslie and Gillan10 showed how to properly account for a point charge

_q_ interacting with its periodic images through an isotropic dielectric medium. The approach was expanded by Makov and Payne11 to include the quadrupole moment (_Q_). In practice, _Q_

cannot be determined from the defect charge distribution. Defects come in many forms and their wavefunctions may be localised or delocalised and are invariably coupled to the screening host

charge. In addition, the limitations of a given density functional can require further correction terms, such as valence and conduction band edge shifts, to reduce the divide between

modelling and measurement12. Exciting results and insights were gained using these methods, especially in the area of metal oxides. There were problems, however. Research groups performing

similar simulations would obtain different conclusions depending on the flavour of corrections that were employed; the curious reader can look into the case of defects in ZnO. In my opinion,

the absolute defect energetics reported during this era should be taken with a pinch of salt. EARLY 21ST CENTURY—ROBUST PREDICTIONS To tackle these issues, a new set of correction schemes

emerged for supercell calculations. Freysoldt et al.13 modelled the defect charge as a Gaussian distribution in an isotropic medium. There were other efforts to include anistropic dielectric

screening14,15. Kumagai and Oba16 refined these approaches with a more practical alignment procedure, based on atomic site potentials, that accounts for the full anisotropic low-frequency

dielectric response. More recent developments have moved away from a posteriori corrections of the total energy to direct modification of the underlying self-consistent calculation. The

advantages are that the total energy and electronic eigenvalues can be corrected directly and more physical long-range dielectric screening can be incorporated. A self-consistent potential

correction was proposed by da Silva et al. in 202117. The change in potential, from either a reference pristine supercell or neutral defect, is used to correct for the difference between the

periodic and isolated charged defect. One limitation in the current formalism is the use of an isotropic dielectric constant; however, spatial variation is allowed in one direction for the

case of slabs. In contrast, the image charge correction proposed by Suo et al.18 avoids the input of a dielectric constant at all and is instead based on the self-consistent charge density

difference between charged and neutral defects, which already contains the relevant screening information. Both approaches show promising behaviour for a series of test cases including NaCl

and MgO. An issue not addressed in these two recent works is how to incorporate the low-frequency dielectric response involving ion displacements. This is critical for accurately describing

defect transitions, which may be excited optically or thermally19. Suo et al.18 suggest introducing a Gaussian broadening scheme to capture ion displacements, but this remains to be

implemented and tested. An entirely different approach has been taken by Xiao et al.20 in a move away from the standard jellium model to consider charge compensation by realistic valence or

conduction band edge states of the host crystal. Their self-consistent correction scheme, which avoids the artificial jellium background, is intuitive for traditional semiconductors where

charged defects are compensated by electrons/holes, but less so for cases where ionic compensation dominates21,22. The approach gives good agreement with conventional methods and can also

describe defects in low dimensional structures. This new wave of research and development in the field is exciting and will further increase the predictive power of first-principles

calculations of materials. A family of reliable and general correction schemes for charged defects will allow us to confidently tackle important scientific challenges such as equilibrium

defect distributions, defect vibrations, and non-equilibrium charge transitions. They will also support more robust workflows for defect automation that can be used to identify new behaviour

and physical trends in imperfect crystals. REFERENCES * Gillan, M. J., Harding, J. H. & Leslie, M. A comparison of methods for calculating defect entropies in ionic crystals. _J. Phys.

C_ 21, 5465 (1988). Article Google Scholar * Freysoldt, C. et al. First-principles calculations for point defects in solids. _Rev. Mod. Phys._ 86, 253–305 (2014). Article Google Scholar

* Frenkel, J. Über die wärmebewegung in festen und flüssigen körpern. _Z. Phys._ 35, 652–669 (1926). Article CAS Google Scholar * Mott, N. F. & Littleton, M. J. Conduction in polar

crystals. I. electrolytic conduction in solid salts. _Trans. Farad. Soc._ 34, 485–499 (1938). Article CAS Google Scholar * Catlow, C. R. A. Mott–littleton calculations in solid-state

chemistry and physics. _J. Chem. Soc._ 85, 335–340 (1989). CAS Google Scholar * Pantelides, S. T. The electronic structure of impurities and other point defects in semiconductors. _Rev.

Mod. Phys._ 50, 797 (1978). Article CAS Google Scholar * Xie, Z. et al. Demonstration of the donor characteristics of Si and O defects in gan using hybrid QM/MM. _Phys. Stat. Solidi (a)_

214, 1600445 (2017). Article Google Scholar * Baraff, G. A. & Schlüter, M. New self-consistent approach to the electronic structure of localized defects in solids. _Phys. Rev. B_ 19,

4965–4979 (1979). Article CAS Google Scholar * Zunger, A. & Lindefelt, U. Theory of substitutional and interstitial 3_d_ impurities in silicon. _Phys. Rev. B_ 26, 5989–5992 (1982).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Leslie, M. & Gillan, M. J. The energy and elastic dipole tensor of defects in ionic crystals calculated by the supercell method. _J. Phys. C_ 18, 973–982

(1985). Article CAS Google Scholar * Makov, G. & Payne, M. C. Periodic boundary conditions in ab initio calculations. _Phys. Rev. B_ 51, 4014–4022 (1995). Article CAS Google Scholar

* Lany, S. & Zunger, A. Assessment of correction methods for the band-gap problem and for finite-size effects in supercell defect calculations: Case studies for ZnO and GaAs. _Phys.

Rev. B_ 78, 2637–25 (2008). Google Scholar * Freysoldt, C., Neugebauer, J. & Van de Walle, C. G. Fully ab initio finite-size corrections for charged-defect supercell calculations.

_Phys. Rev. Lett._ 102, 016402 (2009). Article Google Scholar * Rurali, R. & Cartoixà, X. Theory of defects in one-dimensional systems: application to Al-catalyzed Si nanowires. _Nano

Lett._ 9, 975–979 (2009). * Murphy, S. T. & Hine, N. D. M. Anisotropic charge screening and supercell size convergence of defect formation energies. _Phys. Rev. B_ 87, 094111 (2013).

Article Google Scholar * Kumagai, Y. & Oba, F. Electrostatics-based finite-size corrections for first-principles point defect calculations. _Phys. Rev. B_ 89, 195205 (2014). Article

Google Scholar * da Silva, M. C. et al. Self-consistent potential correction for charged periodic systems. _Phys. Rev. Lett._ 126, 076401 (2021). Article Google Scholar * Suo, Z.-J., Luo,

J.-W., Li, S.-S. & Wang, L.-W. Image charge interaction correction in charged-defect calculations. _Phys. Rev. B_ 102, 174110 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gake, T., Kumagai,

Y., Freysoldt, C. & Oba, F. Finite-size corrections for defect-involving vertical transitions in supercell calculations. _Phys. Rev. B_ 101, 020102 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar

* Xiao, J. et al. Realistic dimension-independent approach for charged-defect calculations in semiconductors. _Phys. Rev. B_ 101, 165306 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Walsh, A.,

Scanlon, D. O., Chen, S., Gong, X. & Wei, S.-H. Self-regulation mechanism for charged point defects in hybrid halide perovskites. _Angew. Chem._ 127, 1811–1814 (2015). Article Google

Scholar * Walsh, A. & Zunger, A. Instilling defect tolerance in new compounds. _Nat. Mater._ 16, 964–967 (2017). Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I

thank Seán R. Kavanagh for a careful reading of the paper. Support was received from the Faraday Institution (faraday.ac.uk; EP/S003053/1), grant No. FIRG025. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND

AFFILIATIONS * Department of Materials, Imperial College London, London, UK Aron Walsh * The Faraday Institution, Quad One, Didcot, UK Aron Walsh * Department of Materials Science and

Engineering, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea Aron Walsh Authors * Aron Walsh View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS A.W. wrote the

article. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Aron Walsh. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The author declares no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit

to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are

included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and

your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this

license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Walsh, A. Correcting the corrections for charged defects in

crystals. _npj Comput Mater_ 7, 72 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00546-0 Download citation * Received: 18 March 2021 * Accepted: 26 April 2021 * Published: 21 May 2021 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-021-00546-0 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative