- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Tumour-associated KRAS mutations are the most prevalent in the three RAS-family isoforms and involve many different amino-acids. Therefore, molecules able to interfere with mutant

KRAS protein are potentially important for wide-ranging tumour therapy. We describe the engineering of two RAS degraders based on protein macromolecules (macrodrugs) fused to specific E3

ligases. A KRAS-specific DARPin fused to the VHL E3 ligase is compared to a pan-RAS intracellular single domain antibody (iDAb) fused to the UBOX domain of the CHIP E3 ligase. We demonstrate

that while the KRAS-specific DARPin degrader induces specific proteolysis of both mutant and wild type KRAS, it only inhibits proliferation of cancer cells expressing mutant KRAS in vitro

and in vivo. Pan-RAS protein degradation, however, affects proliferation irrespective of the RAS mutation. These data show that specific KRAS degradation is an important therapeutic strategy

to affect tumours expressing any of the range of KRAS mutations. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS A PAN-KRAS DEGRADER FOR THE TREATMENT OF KRAS-MUTANT CANCERS Article Open access 28

June 2024 INHIBITION AND DEGRADATION OF NRAS WITH A PAN-NRAS MONOBODY Article Open access 08 October 2024 CANCER THERAPIES BASED ON TARGETED PROTEIN DEGRADATION — LESSONS LEARNED WITH

LENALIDOMIDE Article 02 March 2021 INTRODUCTION Mutations of the _KRAS_ oncogene represent more than 85% of all RAS family mutations1 and individual mutations occur at various codons giving

rise to many forms of mutant KRAS protein2. Recently, several macromolecules3,4,5,6,7 and compounds8,9,10,11,12,13 have been developed that influence the function of RAS family members.

Nevertheless, only the G12C mutation of KRAS has been specifically targeted by small molecules by virtue of covalent binding of the compounds to the mutant cysteine14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Several small molecules are now in clinical trials22. However, only a small portion of mutant KRAS tumours expresses a KRASG12C protein (around 12%, Cosmic database v91,

https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic) and can be targeted by these inhibitors. Furthermore, upon treatment with these inhibitors, a rapid adaptation has been recently described in the KRASG12C

tumour population such that some cells become drug-insensitive23. Therefore, new strategies are needed to specifically target the larger number of other tumours expressing mutant KRAS.

Reagents that could potentially be applied to this objective are designed ankyrin repeat proteins (DARPins) K13 and K19 that interfere specifically with KRAS3. While these DARPins do not

discriminate mutant from wild-type KRAS (KRASWT), they do not bind to NRAS and HRAS so that any phenotype engendered using these DARPins within cells would spare the expression, and

function, of these two family members3. Previous studies involving expression of a pan-RAS-binding intracellular single domain antibody (iDAb, hereafter called iDAb RAS) in human cell line

xenografts demonstrated that tumour growth was inhibited for the duration of expressing the intracellular antibody fragment and resumed when the antibody was removed24. A potential

complementary direction in this context could be the addition of warheads to these macromolecules25, such as single chain Fragment variable (scFv) fused to proteasome targeting sequences26

or E3 ligases engineered on intracellular single domains, called macrodrug degraders, that have been shown to invoke proteolysis of targets27,28,29,30,31,32. Macromolecule degraders induce

the depletion of their target via the ubiquitin-proteasome system. They consist of a binder targeting a protein of interest (e.g. intracellular single domain), a linker and an E3 ligase

domain. A similar protein target degradation strategy has been developed in which small molecules that bind proteins are linked to E3 ligase-binding ligands called proteolysis targeting

chimeras (PROTACs) or small molecule degraders33,34. The main advantage of the proteolysis strategy is that only a binder is required, and the binder does not need to inhibit the function of

the protein. Indeed, unlike classical protein–protein inhibitors or other occupancy-driven inhibitors, the degraders rely on an event-driven mode of action and are consequently often more

potent than the parental entity35,36,37,38,39. Most of the current degraders target bromodomains or kinase families40,41,42,43 and only a few target “undruggable” proteins such as

transcription factors44. The only PROTACs thus far applied to RAS are compounds that bind KRASG12C but these only degrade exogenous GFP–KRASG12C fusion protein and do not target endogenous

KRASG12C45. In addition, no macromolecule or small molecule-based degrader has been shown to be specific to KRAS in the RAS family of oncogenic targets. We report here the engineering of the

KRAS-specific DARPin K19 (herein referred to as DP KRAS)3 into a KRAS-specific degrader and compare the efficacy and tumour-specificity with an engineered pan-RAS degrader, made from the

previously described pan-RAS intracellular single domain antibody7,46. We show that the KRAS degrader efficiently induces endogenous KRAS degradation in vitro and in vivo and specifically

inhibits mutant KRAS tumours without affecting cells with only KRASWT, whereas the pan-RAS degraders inhibit all type of cells, regardless of the RAS isoform mutation. Therefore, we exploit

this KRAS-specific macrodrug to demonstrate that KRAS ablation can be an attractive way to target any mutant KRAS-expressing tumour. RESULTS ENGINEERING KRAS-SPECIFIC AND PAN-RAS DEGRADERS

The addition of warheads to intracellular antibodies and other macromolecular reagents is an implied strategy to increase efficacy, for example via the transfer of target proteins to the

proteasome for degradation. Intracellular single domains have been functionalised with E3 ligase domains, such as the UBOX domain of the carboxyl terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP)

ligase31, the Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL)29,32 or FBOX27,28 but there are no rules about which E3 ligase is applicable in specific cases nor how the protein should be engineered (N or C

terminal fusion with the E3 ligase). We have tested both the UBOX domain and VHL E3 ligase fused to the specific DP KRAS3 or the iDAb RAS7. Controls comprised a mutant DARPin where the

RAS-binding tryptophan repeats are mutated into glycine and alanine residues3 (herein DP Ctl) or a non-relevant iDAb (herein iDAb Ctl)47. All the proteins were engineered with either N or

C-terminal fusions with each E3 ligase. Accordingly, DP Ctl does not bind to KRAS (mutant and WT) as shown by Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) donor saturation assays

(Supplementary Fig. 1a) and by co-immunoprecipitation (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Furthermore, like the negative control DARPin E3.54, the DP Ctl mutant does not inhibit mutant KRAS/CRAFFL

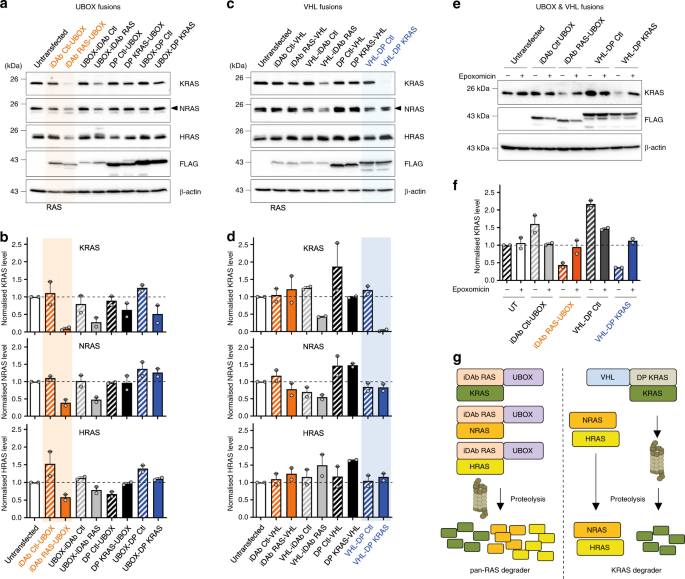

interaction (Supplementary Fig. 1c) or mutant KRAS dimerisation in BRET competition assays (Supplementary Fig. 1d). HCT116 cells (which express KRASG13D) were transiently transfected with

these UBOX/single domain constructs and K/N/HRAS protein levels were monitored by Western blot. The iDAb RAS-UBOX and UBOX-iDAb RAS constructs both induced a decrease of KRAS, NRAS and HRAS

protein levels, and the iDAb RAS-UBOX showing greater degradation (Fig. 1a, b). Conversely, we could detect little RAS turnover by the C-terminal VHL fusion with the iDAb RAS (i.e. iDAb

RAS-VHL), although some degradation was observed with the N-terminal VHL fusion (i.e. VHL-iDAb RAS) (Fig. 1c, d). Similarly, UBOX fusions with the DP KRAS showed little effect on RAS protein

levels (Fig. 1a, b). However, when we engineered a VHL fusion at the N-terminus of DP KRAS (VHL-DP KRAS), we observed a substantial decrease of KRAS protein in the transfected HCT116 cells

(Fig. 1c, d). VHL-DP KRAS fusion diminished KRAS protein level much more than DP KRAS-VHL fusion (Fig. 1d). A key observation is that, unlike iDAb RAS-UBOX, VHL-DP KRAS only depleted KRAS

and not NRAS or HRAS (Fig. 1c, d) due to the KRAS-specific binding property of this DARPin3. These degradation effects were proteasome dependent as epoxomicin treatment (a proteasome

inhibitor48) impeded RAS degradation for the iDAb-UBOX and the VHL-DP KRAS (Fig. 1e, f). Therefore, the functionalisation of iDAb RAS with UBOX domain (hereafter called pan-RAS degrader) and

DP KRAS with VHL (hereafter named KRAS degrader) promotes RAS and KRAS degradation, respectively (Fig. 1g, the sequences in Supplementary Figs. 1e and 2–4). KRAS DEGRADER SPECIFICALLY

DEPLETES KRAS IN CANCER CELLS We performed a comparison of the KRAS-specificity of the KRAS degrader with the pan-RAS degrader in a stably transduced H358 (lung, KRASG12C) cancer cell line.

The engineered proteins were expressed using a Tet-On inducible system (i.e. degrader expression is induced after doxycycline treatment) in cells transduced with lentiviral vectors. We first

characterised the degrader properties in these H358 cells with an increasing dose of doxycycline induction, demonstrating a depletion of only KRAS with the KRAS degrader while the pan-RAS

degrader knocked down all three K/N/HRAS proteins, in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2a, b). No effect was observed with the control degraders (Fig. 2a, b). These results confirmed the

specificity of degradation observed in the transient transfection experiments shown in Fig. 1. We analysed the kinetics of RAS protein degradation following doxycycline induction of either

the pan-RAS degrader or the KRAS degrader and the resultant effects of RAS-dependent downstream signalling. The synthesis of degrader proteins (detected using Western blot with anti-FLAG

antibody) could be observed in as little as 2 h after doxycycline treatment (Fig. 2c, d) and the loss of K, N and HRAS followed with similar profiles from 2 h when the pan-RAS degrader was

expressed (Fig. 2c). However, only the KRAS level was reduced when the KRAS degrader was expressed and the KRAS reduction was concomitant with the degrader expression (Fig. 2d). As expected,

we also observed loss of phosphorylation of AKT, MEK and ERK in parallel with either degrader synthesis (Fig. 2e, f). RAS degradation was confirmed to be proteasome-dependent by treating

cells with the proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin (Supplementary Fig. 5a). In addition, consistent with the potent inhibition of MAPK pathway activity, both pan-RAS and KRAS degraders reduced

the expression of the MAPK pathway downstream transcript _DUSP6_ (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Our data demonstrate the KRAS-specific degrader causes rapid depletion of KRAS coupled to an

inhibition of RAS downstream signalling and sustained degradation of KRAS over the doxycycline treatment period (as long as 72 h). The pan-RAS degrader shows similar properties. We also

assessed the specificity of degradation of both degraders in several stably-transduced cancer cell lines in addition to H358, namely MIA PaCa2 (pancreas, KRASG12C), A549 (lung, KRASG12S),

H1299 (lung, NRASQ61K), HT1080 (fibrosarcoma, NRASQ61K), T24 (bladder, HRASG12V), HCC827 (lung, RASWT but EGFR mutated) and an untransformed cell line: MRC5 (non-transformed lung fibroblast,

RASWT). The engineered proteins were again expressed using a Tet-On inducible system in cells transduced with lentiviral vectors. The degrader expression was detected in Western blots using

anti-FLAG tag antibody on induction by doxycycline (Fig. 3) causing efficient knockdown of K, N and HRAS in cells expressing the pan-RAS degrader (Fig. 3a) or degradation of KRAS only when

the KRAS degrader was expressed (Fig. 3b). This occurred in all the cell lines tested. KRAS DEGRADER INHIBITS RAS SIGNALLING OF MUTANT KRAS CELLS The kinetics of RAS degradation in H358

cells was examined to determine the initiation and duration of effects on RAS signalling (Fig. 2). We further evaluated the consequences of pan-RAS or KRAS-only degradation on RAS downstream

signalling pathways of the panel of cell lines using Western blots 72 h after induction with doxycycline. The pan-RAS degrader induced loss of RAS proteins which resulted in the inhibition

of RAS signalling (either PI3K and/or MAPK pathways). This was determined by reduction in phosphorylation of AKT, MEK and/or ERK, in all the cell lines, although not all proteins in the MAPK

and PI3K pathways were similarly affected (Figs. 4 and 5i). Loss of RAS signalling was also observed in two lines without _RAS_ gene mutations (Fig. 4g, h), whereas the control iDAb

Ctl-UBOX had no effect (Fig. 4a–h). Conversely, the KRAS degrader only inhibited AKT, ERK and MEK phosphorylation in those cells with mutant KRAS, namely H358, MIA PaCa2 and to a lesser

extent in A549 (Fig. 5a–c, i). Indeed, it had no consequence on cells with mutation of NRAS (H1299 and HT1080) or HRAS (T24) or without mutant RAS (HCC827 and MRC5) (Fig. 5d–h). The VHL-DP

Ctl had no effect (Fig. 5). These data are quantified in Fig. 5i. It has been previously reported that the conversion of a parental binder into a degrader could change its

specificity49,50,51, so we added the parental binders as controls in our study. Expression of the pan-RAS iDAb fused to GFP2 resulted in reduced RAS levels in H358, A549 and T24

(Supplementary Fig. 6a–h) that could be due to the level of expression of the iDAb RAS, while the KRAS-specific DARPin fused to GFP2 had no effect on the levels of RAS proteins

(Supplementary Fig. 7a–h). The iDAb RAS-GFP2 had a similar inhibitory output on RAS downstream pathways than its degrader version (Supplementary Figs. 6a–h and 7i for quantification). The

KRAS-specific DARPin fused to GFP2 also decreased RAS signalling in mutant KRAS cells (H358, MIA PaCa2 and A549 in Supplementary Fig. 7a–c, i), whereas it altered RAS signalling differently

in the other cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 7d–i). Indeed, it augmented MEK and ERK phosphorylation, while it decreased or had no effect on pAKT levels in H1299, HT1080 and T24 cells, which

have mutant NRAS or HRAS (Supplementary Fig. 7d–f, i) and diminished pERK and pAKT in HCC827 and MRC5 cell lines lacking RAS mutation (Supplementary Fig. 7g–i). The KRAS-specific DARPin

interacts with KRAS-GTP and KRAS-GDP and may be a GAP inhibitor3, therefore, the increase of pMEK/pERK signals might be attributed to its GAP inhibitory mechanism on KRASWT. KRAS DEGRADER

INHIBITS MUTANT KRAS CELLS PROLIFERATION Our data showed that the KRAS-specific DARPin K19 engineered into a degrader has focused specificity towards mutant KRAS cells compared to the

parental DARPin. We assessed the effect of KRAS or pan-RAS degradation on the proliferation of our panel of cell lines with inducible macrodrugs by testing the proliferation in 2D-adherent

and 3D spheroid assays. The pan-RAS degrader inhibited proliferation of all the cell lines, in both 2D-adherent or 3D spheroid assays (Fig. 6a–h) including MRC5 which is non-transformed and

has wild-type RAS. This was also observed with the parental iDAb RAS-GFP2 in 2D-adherent proliferation assays (Supplementary Fig. 8a–h). The KRAS degrader specifically reduced proliferation

of cells with mutant KRAS expression in 2D-adherent and 3D spheroid assays (Fig. 6a–c) but did not modify the proliferation of cancer cell lines with mutant NRAS or HRAS (Fig. 6d–f) nor of

the RASWT cells HCC827 and MRC5 (Fig. 6g, h). These data concur with the effect of the KRAS degrader described on RAS signalling pathways in Fig. 5. On the contrary, the parental DARPin

KRAS-GFP2, like the pan-RAS iDAb-GFP2 and the pan-RAS degrader, decreased the 2D-adherent proliferation of all the stable cell lines (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 8a–h), endorsing the benefit

of engineering the DARPin KRAS into a KRAS-specific degrader. The pan-RAS and the KRAS degraders both inhibited proliferation in H358 cells by inducing programmed cell death indicated by

evidence of the apoptosis markers of cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 3, starting from 16–24 h after doxycycline addition, with the highest response at 72 h (Fig. 7a). Consequently, we

evaluated the induction of apoptosis markers after 72 h of degrader expression in all the stable cell lines. The KRAS degrader and pan-RAS induced cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP in H358 and

MIA PaCa2 cell lines but also in A549 cells upon expression of the pan-RAS degrader only (Fig. 7b). The other cell lines showed little cleaved PARP or caspase 3 compared to the negative

controls (Fig. 7b, c). These results suggest that the KRAS degrader blocked proliferation of cells expressing mutant KRAS by inducing apoptosis in KRAS dependent cells (i.e. H358 and MIA

PaCa2), while it did not in KRAS independent cells (A549) in the 2D-adherent culture method52,53. KRAS DEGRADER INDUCES REGRESSION OF MUTANT KRAS TUMOURS We finally determined whether the

degraders could be efficient in subcutaneous xenograft mouse models. From our previously established H358 and H1299 stable cell lines, we isolated unique clones of pan-RAS/KRAS degraders

that would additionally express a _Firefly Luciferase_ (FLuc) to detect the tumour in vivo. These individual clones were characterised in vitro by Western blot and growth curves. Induction

of the expression of pan-RAS and KRAS degraders in H358 inhibited RAS downstream signalling pathways (Supplementary Fig. 9a) and strongly impeded the cell growth (Supplementary Fig. 9b).

Only the pan-RAS degrader had an inhibitory effect on the RAS signalling pathways and the cell growth of H1299 cells (Supplementary Fig. 9a, c) while the KRAS degrader had no effect, on

either, in H1299 (Supplementary Fig. 9a, c). The growth of doxycycline-inducible cells in vivo was examined by subcutaneously injecting cells in nude mice to establish xenograft models.

While the pan-RAS degrader significantly impeded H1299 tumours burden (Supplementary Fig. 9d), the KRAS degrader caused almost no inhibition (Supplementary Fig. 9e). However, expression of

both pan-RAS and KRAS degraders in mutant KRAS H358 xenografts induced regression of tumours after only 3 days of doxycycline treatment with a substantial regression of all tumours after 20

days of treatment (Fig. 8a–d). In order to analyse RAS downstream signalling in H358 xenografts, two mice were treated with doxycycline for 48 h before Western blot analysis of their tumour

compared to the non-treated tumours because the doxycycline treated tumours regressed and could not be resected after 20 days of treatment. After 48 h of doxycycline, we observed a large

decrease in phosphorylation of MEK and ERK in H358 pan-RAS and KRAS degraders in parallel with degradation of their RAS target(s) (Fig. 8e, f). In contrast, in H1299 tumours, 20 days after

treatment, we detected a decrease of phosphorylation of MEK and ERK kinases in tumours expressing the pan-RAS degrader (Supplementary Fig. 9f) and not the KRAS degrader (Supplementary Fig.

9g). In conclusion, our in vitro and in vivo data show that even though the KRAS degrader depletes both endogenous KRASWT and KRASMUT, it only inhibits cancer cells expressing mutant KRAS.

DISCUSSION Effective cancer therapy based on developing reagents to intracellular targets that comprise families of proteins should ideally incorporate specific targeting of individual

family members. The RAS family is an important example in which three isoforms exist, each of which can undergo mutation in various tumour types. KRAS protein is the most often mutated

isoform in human cancers, principally resulting from base changes causing single amino acid changes that are spread throughout the protein, but in mutational hotspots2. Therefore, targeting

mutant KRAS is challenging due to the number of different mutations and the high sequence identity between the three RAS isoforms (more than 80%). However, our recently described

KRAS-specific DARPins showed the feasibility to specifically target both wild-type and mutant KRAS by binding on the allosteric lobe of RAS3. The addition of warheads to intracellular

antibodies such as fusing procaspase to induce apoptosis54,55 or FBOX proteins to cause proteolysis27,28 provides a mechanism by which macromolecules could be converted to potent macrodrugs.

While PROTAC small molecules have been described and are KRASG12C specific due to covalent interaction of compound to the protein45, they did not degrade endogenous KRASG12C. In addition,

an affinity-directed protein missile system has shown degradation of KRAS and HRAS56, but so far no isoform specific RAS degraders have been found. In this study, we demonstrate a way

forward to generalised KRAS inhibitors by engineering a KRAS-specific DARPin as a fusion protein with an E3 ligase to invoke proteasome targeting of KRAS and subsequent degradation. We have

engineered our KRAS-specific DARPin with an E3 ligase warhead and compared this to an engineered pan-RAS binding iDAb46. We found that RAS degradation could readily be achieved with both

macrodrugs but that the specific E3 ligase and the terminal location of the E3 ligase on the macrodrug was important. Interestingly, the VHL E3 ligase was most efficient with the KRAS

binding DARPin and the UBOX domain from CHIP E3 ligase with the pan-RAS iDAb. Both degraders allowed the efficient depletion of endogenous RAS proteins in multiple cell lines (i.e. from

lung, pancreas, bladder and connective tissue) suggesting a broad applicability of this strategy. Furthermore, we showed the high specificity of the KRAS degrader that only depletes KRAS

without affecting HRAS or NRAS protein level in all the cell lines tested. Therefore, the properties of the RAS degraders would make them useful tools for studying RAS and KRAS biology in

cells. It is possible that the degraders function by co-degradation with the target RAS protein or by a catalytic mechanism. Supplementary Fig. 5a shows that the protein levels of all iDAbs

and DARPins (non-relevant and relevant) increased when a proteasome inhibitor was added suggesting that the turnover of these exogenous proteins is dependent on the proteasome machinery. In

short time courses (up to 24/48 h, Fig. 2c), the effects of the degraders on RAS degradation could be catalytic as there was no apparent decrease of the degrader protein levels but at longer

times (>48 h) the degrader protein levels decreased more than the negative controls, suggesting a co-degradation. As previously described, we also observed that the degrader technology

can modify the potency and/or the selectivity of the parental binder49,50,51 as presented in this study with the DP KRAS. We show that the parental DP KRAS affected RAS downstream signalling

pathways and the proliferation of all the cell lines tested, showing no specificity towards mutant KRAS cells. This could be attributed to its ability to modulate mutant and wild-type KRAS

on multiple levels3. However, once converted into a KRAS degrader, it only inhibited mutant KRAS cancer cells, while the pan-RAS degrader showed no specificity for any RAS isoform mutant

protein like the parental binders iDAb RAS and DP KRAS. An important finding of our study is that KRASWT depletion by KRAS degrader did not lead to an inhibition of the proliferation of

RASWT cells, especially untransformed cells. These data are supported by a previous study showing that expression of only one RAS in RASless mouse embryonic fibroblast did not impede their

ability to proliferate while only the removal of the three RAS isoforms stopped the growth of these engineered fibroblast cells57. This conclusion was confirmed in multiple cell lines with

the pan-RAS degrader described here, strongly suggesting that mechanisms of compensation exist between the three RAS isoforms in RASWT cells in a way that loss of expression of one (or two)

of the isoforms can be overcome via the expression of the other isoform(s). In addition, our data highlighted the efficacy of our KRAS degrader in vivo, with a rapid regression of mutant

KRAS tumours. Therefore, KRAS-targeted degradation is an attractive therapeutic strategy for cancers with KRAS mutations, and not limited to any specific codon change. Our study shows a

proof of concept for the development of pan-KRAS specific degraders as therapeutics that could be implemented in any cancer with KRAS mutations. The direct therapeutic use of these

inhibitors with an intracellular protein such as KRAS is currently limited, but efforts have been made for the delivery of macromolecules by mRNA58 or other delivery strategies59. METHODS

CELL CULTURE A549, H358, HCT116, HEK293T, HT1080, MIA PaCa2 cells were grown in DMEM medium (Life Technologies), H1299, HCC827, T24 cells in RPMI medium (Life Technologies) and MRC5 in MEMα

medium (Life Technologies). All cell lines were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies). Cells were grown at 37 °C with 5%

CO2. The cell lines were obtained from ATCC (catalogue numbers provided in the Reporting Summary) except MRC5, T24 and H1299, which were a gift from Prof. Geoff Higgins, University of

Oxford, and MIA PaCa2 from Prof. Gillies McKenna. Characterisation of the cell lines was achieved by cloning and sequencing of the K, N and HRAS cDNA from each line. MIA PaCa2 was

authenticated by short-tandem repeat DNA profiling services (ATTC). All cell lines were tested to confirm that they were free of mycoplasma. CELL TRANSFECTION HEK293T cells were seeded in

6-well plates (650,000 cells per well) and 2 μg of plasmid DNA was transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo-Fisher, see also “BRET2 methods” section below). HCT116 cells were seeded in

6-well plates (650,000 cells per well). Cells were transfected 24 h later with 2.5 μg of plasmid, 8.75 μL of Lipofectamine LTX and 2.5 μg of PLUSTM Reagent (Thermo-Fisher) for another 24 h

before Western blot analysis. MOLECULAR CLONING All RAS cDNAs (KRASG12D, KRASWT, NRASQ61H and HRASG12V-CAAX) were cloned into the pEF-RLuc8-MCS, pEF-GFP2-MCS or pEF-3xFLAG-MCS plasmids,

full-length CRAFS257L was cloned into pEF-GFP2-MCS and DARPin were cloned into the pEF-MCS-GFP2 or pEF-MCS-mCherry plasmid. The cloning details of all these plasmids are described

elsewhere3,12,60. Full-length VHL (amino acids 1–213) and UBOX domain (amino acids 128–303 from the CHIP E3 ligase) were cloned into PmlI/XhoI sites of the pEF-GFP2-MCS or into NotI/XbaI

sites of the pEF-MCS-GFP2 plasmids to replace the GFP2 moiety. Linkers, DARPins and iDAbs were inserted into pEF-VHL-MCS and pEF-UBOX-MCS using XhoI/XbaI sites or into pEF-MCS-UBOX and

pEF-MCS-VHL using PmlI/NotI sites. A single FLAG tag was added by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) at the carboxy terminal end of the DARPin degrader vectors or on the amino terminal end of

the iDAb degrader vectors. VHL-DP KRAS-FLAG, VHL-DP Ctl-FLAG, FLAG-iDAb RAS-UBOX and FLAG-iDAb Ctl-UBOX sequences were cloned in the TLCV2 lentivector (Addgene plasmid #8736061) by PCR using

AgeI/NheI sites. Coding region DNA and protein sequences of these four constructs are shown in Supplementary Figs. 1e and 2–4. LENTIVIRUS PRODUCTION For each virus produced, 4.5 × 106

HEK293T cells were seeded per 100 mm dish (7 × 100 mm dishes per virus production) in 9 mL of complete DMEM. Twenty-four hours later, cells were transfected with 12 μg of the TLCV2 construct

of interest (i.e. VHL-DP KRAS-FLAG, VHL-DP Ctl-FLAG, FLAG-iDAb RAS-UBOX and FLAG-iDAb Ctl-UBOX), 8 μg of psPAX2, 3 μg of pMD2.G (the latter are lentiviral packaging and envelope vectors,

respectively) and 46 μL of Lipofectamine 2000 (quantities for one 100 mm dish). The supernatants were collected 48 h after transfection, centrifuged 5 min at 640 × _g_, filtered (0.45 μm

filter) and centrifuged 2 h at 48,000 × _g_ at 4 °C. The virus from 7 × 100 mm dishes was resuspended in 250 μL of PBS. VIRAL TRANSDUCTION AND MACRODRUG EXPRESSION Cells were transduced with

the appropriate lentiviruses for 48 h in 6-well plate in 1 mL of medium containing 8 μg.mL−1 of polybrene (Sigma, Cat#107689). Transduced cells were selected with puromycin (MP Biomedicals,

Cat#194539). The puromycin concentrations used for selection of each cell line were 0.5 μg.mL−1 for A549 and HCC827 cell lines, 0.75 μg.mL−1 for H358, MIA PaCa2 and HT1080 cell lines, 0.8

μg.mL−1 for H1299 and MRC5 cell lines and 1 μg.mL−1 for T24 cell line. Doxycycline (Sigma, Cat#D9891) was used to induce the expression of macrodrug E3-ligase or macrodrug GFP2 fusions or

controls from the TLCV2 lentivector. The doxycycline induction was carried out by addition of stock solution (100 μg.mL−1) to culture medium and continued incubation at 37 °C. For proteasome

inhibition, epoxomicin (Sigma, Cat#E3652) was used at 0.8 μM for 18 h followed by protein analysis. ESTABLISHMENT OF H358 AND H1299-FLUC STABLE CLONES H358 and H1299 cells expressing VHL-DP

KRAS and iDAb RAS-UBOX were transfected with pEF-FLuc24 using Lipofectamine LTX following the manufacturer recommendations. After 48 h of transfection, cells were selected with 1 mg.mL−1 of

G418 (Sigma, Cat#A1720) and clones were picked and characterised. QUANTITATIVE REAL-TIME PCR (QRT-PCR) H358 cells were plated at 0.8 × 106 cells per well in a 6-well plate. After 24 h, the

cells were treated or not with 0.2 μg.mL−1 of doxycycline for 24 h. Cell were lysed in 1 mL of TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) per 6 well. Total RNA was extracted with the Direct-zolTM

RNA miniprep (Zymo Research) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was eluted with 15 μL of nuclease-free H2O. cDNA was synthesised from 1.5 μg of total RNA per condition using

SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed with 400 nM primers, diluted with 12.5 μL Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in a final volume of 25 μL.

RT-PCR experiments were performed with the following protocol on a 7500 Fast (Applied Biosystems): 95 °C for 20 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 3 s, and 60 °C for 30 s. qRT-PCR samples were

performed and analysed in duplicate, from two independent experiments. GAPDH was used for normalisation. Primers used in this study are as follows: DUSP6For: 5ʹ CTCGGATCACTGGAGCCAAAAC 3ʹ

DUSP6Rev: 5ʹ GTCACAGTGACTGAGCGGCTAA 3ʹ GAPDHFor: 5ʹ GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG 3ʹ GAPDHRev: 5ʹ ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA 3ʹ BRET2 ASSAYS AND MEASUREMENTS For all BRET experiments (titration curves

and competition assays) 650,000 HEK293T cells were seeded in each well of a 6-well plate. After 24 h at 37 °C, cells were transfected with a total of 1.6 μg of DNA mix (with donor + acceptor

± competitor plasmids), using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Thermo-Fisher). Cells were detached after 24 h, washed with PBS and seeded in a white 96-well plate (clear bottom,

PerkinElmer) in OptiMEM no phenol red medium complemented with 4% FBS. Cells were incubated for an additional 20–24 h at 37 °C before the BRET assay reading. A step-by-step protocol is

provided elsewhere60. BRET2 signal was determined immediately after injection of coelenterazine 400a substrate (10 μM final) to cells (Cayman Chemicals), using a CLARIOstar instrument (BMG

Labtech) with a luminescence module. 2D AND 3D CELL PROLIFERATION ASSAYS Cells were seeded in white 96-well plates (clear bottom, PerkinElmer, Cat#6005181) for 2D-adherent proliferation

assays or in ultra-low attachment 96-well plates (Corning, Cat#7007) for 3D spheroid assays. All cell seeding was optimised to maintain linear growth over the time of the assay. The

following day, a 10× doxycycline solution was prepared (1–2 μg.mL−1 for 0.1–0.2 μg.mL−1 final concentration). Cells were incubated in the presence of the doxycycline for 6 days. Cell

viability was analysed every two days using CellTiter-Glo (Promega, Cat#G7572) by incubation with the cells for 15 min. Cell viability was determined by normalising doxycycline-treated cells

to non-treated cells. Cells from the ultra-low attachment plates were transferred into a white 96-well plate (Greiner, Cat#655075) before reading on a CLARIOstar instrument. CELL GROWTH

ASSAY OF H358-FLUC AND H1299-FLUC CLONES Totally, 40,000 of H358-FLuc (iDAb RAS-UBOX or VHL-DP KRAS) or 50,000 of H1299-FLuc (iDAb RAS-UBOX or VHL-DP KRAS) cells were seeded per well of

6-well plate (each condition done in duplicate). After 24 h, medium alone (−dox) or medium containing 0.2 μg.mL−1 doxycycline (+dox) was added in each well. Viable cells were counted with a

haematocytometer and trypan blue every 2 days. IMMUNO-PRECIPITATION ASSAY HEK293T cells were transfected for 24 h with pEF-3xFLAG-KRASWT or pEF-3xFLAG-KRASG12D and pEF-DARPins-GFP2 plasmids.

Cells were washed once with PBS and lysed in the immuno-precipitation buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol and 0.5% Triton X-100) supplemented with protease

inhibitors (Sigma, Cat#P8340) and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo-Fisher, Cat#1862495) for 20 min. Lysates were centrifuged for 15 min and the supernatant incubated with protein G magnetic

beads (Life Technologies, Cat#10004D) and anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma, Cat#F3165). The complexes were incubated for 4 h at 4 °C with rotation. Beads were washed 5 times with the IP buffer,

before the bound proteins were eluted with 1× loading buffer and resolved on 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). WESTERN BLOT ANALYSIS Cells were

washed once with PBS and lysed in SDS-Tris buffer (STB: 1% SDS, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Sigma) and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo-Fisher). Cell lysates

were sonicated with a Branson Sonifier. Mouse tumours were lysed in the radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris,

pH 8.0) with a ratio of 200 μL of lysis buffer for 10 mg of tumour and homogenised with an electric disperser (T10 basic ULTRA-TURRAX, IKA) until the tissue was liquefied. The lysate was

incubated on ice for 1 h, followed by centrifugation at 16,100 × _g_ at 4 °C and the supernatant was collected. The protein concentrations from cell and tumour lysates were determined by

using the Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo-Fisher). Equal amounts of protein (20–50 μg) were resolved on 10 or 12.5% SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride

membrane (GE Healthcare). The membrane was blocked either with 10% non-fat milk (Sigma, Cat#70166) or 10% bovine serum albumin (Sigma, Cat#A9647) in TBS-0.1% Tween20 and incubated overnight

with primary antibody at 4 °C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with horse radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at 20 °C. The membrane was washed with TBS-0.1%

Tween and developed using Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad) and CL-XPosure films (Thermo-Fisher) or the ChemiDoc XRS + imaging system (Bio-Rad). Primary antibodies include

anti-phospho-p44/22 MAPK (pERK1/2) (1/4000, CST, Cat#9101S), anti-p44/42 MAPK (total ERK1/2) (1/1000, CST, Cat#9102S), anti-phospho-MEK1/2 (1/2000, CST, Cat#9154S), anti-MEK1/2 (1/500, CST,

Cat#4694S), anti-phospho-AKT S473 (1/1000, CST, Cat#4058S), anti-AKT (1/1000, CST, Cat#9272S), anti-pan-RAS (1/200, Millipore, Cat#OP40), anti-KRAS (1/100, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies,

Cat#sc-30), anti-NRAS (1/100, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Cat#sc-31 and 1/3000, Abcam, Cat#ab77392), anti-HRAS (1/500, Proteintech, Cat#18295–1-AP), anti-cleaved PARP (1/1000, CST,

Cat#9541), anti-cleaved caspase 3 (1/500, CST, Cat#9664), anti-GFP (1/500, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Cat#sc-9996), anti-FLAG (1/2000, Sigma, Cat#F3165), anti-β-actin (1/5000, Sigma,

Cat#A1978) and anti-αtubulin (1/2000, Abcam, Cat#ab4074). Secondary antibodies include anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked (CST, Cat#7076), anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked (CST, Cat#7074) and anti-goat IgG

HRP-linked (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Cat#2354). HUMAN TUMOUR XENOGRAFT ASSAY IN NUDE MICE Totally, 4.5 × 106 H358-FLuc expressing either iDAb RAS-UBOX clone B2 or VHL-DP KRAS clone F7 or

5 × 106 H1299-FLuc expressing either iDAb RAS-UBOX clone E1 or VHL-DP KRAS clone E5 were injected subcutaneously into the left flank of 5–7-week-old female CD-1 athymic nude mice (Charles

River). The mice were fed with normal diet and water until their subcutaneous tumour reached 3–4 mm diameter (2–3 mm for H1299 cells), approximately 18 days after injection. The mice were

divided into 2 groups of 5 mice (3 mice for H1299-FLuc/VHL-DP KRAS), one of which was supplied with dox (Sigma) via drinking water (2 mg.mL−1 in 20% black-currant juice) and doxycycline diet

(200 mg.kg−1, Special Diets Services). Note on the first day of doxycycline treatment, mice were injected with 100 μL of 4 mg.mL−1 of doxycycline in sterile 0.9% aqueous NaCl by

intraperitoneal injection. One mouse of each of the no doxycycline control groups injected with H358-FLuc/VHL-DP KRAS, H358-FLuc/iDAb RAS-UBOX and H1299-FLuc/VHL-DP KRAS was excluded from

analysis due to lack of tumour development. Subcutaneous tumour growth was monitored by measuring three times weekly with digital calipers (Thermo-Fisher) and by bioluminescence as described

below. Tumour volume was calculated using the formula: tumour volume = (_L_ × _W_2)/2, in which _L_ and _W_ refer to the length and width of the tumour, respectively. Animals were culled in

accordance with Home Office licence restrictions. After humane sacrifice, the mice were dissected for tumours sampling. The University of Oxford Ethical Review Committee approved the study

protocol described in the manuscript. IN VIVO BIOLUMINESCENCE IMAGING (BLI) Bioluminescence was measured in transplanted subcutaneous tumours non-invasively using the IVIS Lumina imaging

system (PerkinElmer) following injection of the luciferase substrate d-luciferin. All of the images were taken after intraperitoneal injection of 150 μL of d-luciferin (stock solution at 30

mg.mL−1 in DPBS, PerkinElmer) corresponding to 150 mg.kg−1 body weight of d-luciferin. BLI were acquired after 5 min of d-luciferin injection. During image acquisition, mice were sedated

continuously by inhalation of 3% isoflurane. Image analysis and bioluminescence quantification was performed using Living Image software (PerkinElmer). QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL

ANALYSIS Quantifications were performed using Image Lab (Biorad), Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software) or Living Image (PerkinElmer). BRET titration curves and statistical analysis were performed

using Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software). The data are typically presented as mean ± SD or SEM as specified in the figure legends. Statistical analyses were performed with an unpaired two-tail

Student’s _t_ test. ns non-significant, *_P_ < 0.05. REPORTING SUMMARY Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY All relevant data are within the paper and its Supplementary Information file and in a Source data file. The source data underlying Figs. 1a–f and 2–8 and Supplementary

Figs. 1b–d and 5–9 are provided as a Source Data file. Additional data supporting the conclusions are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. REFERENCES * McCormick,

F. Progress in targeting RAS with small molecule drugs. _Biochem. J._ 476, 365–374 (2019). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Cox, A. D., Fesik, S. W., Kimmelman, A. C., Luo, J. & Der, C. J.

Drugging the undruggable RAS: mission possible? _Nat. Rev. Drug Discov._ 13, 828–851 (2014). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bery, N. et al. KRAS-specific inhibition using a

DARPin binding to a site in the allosteric lobe. _Nat. Commun._ 10, 2607 (2019). ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Guillard, S. et al. Structural and functional characterization

of a DARPin which inhibits Ras nucleotide exchange. _Nat. Commun._ 8, 16111 (2017). ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Spencer-Smith, R. et al. Inhibition of RAS function

through targeting an allosteric regulatory site. _Nat. Chem. Biol._ 13, 62–68 (2017). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Shin, S.-M. et al. Direct targeting of oncogenic RAS mutants with a

tumor-specific cytosol-penetrating antibody inhibits RAS mutant–driven tumor growth. _Sci. Adv._ 6, eaay2174 (2020). ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tanaka, T., Williams, R.

L. & Rabbitts, T. H. Tumour prevention by a single antibody domain targeting the interaction of signal transduction proteins with RAS. _EMBO J._ 26, 3250–3259 (2007). CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Welsch, M. E. et al. Multivalent small-molecule Pan-RAS inhibitors. _Cell_ 168, 878–889 (2017). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Quevedo, C. E. et

al. Small molecule inhibitors of RAS-effector protein interactions derived using an intracellular antibody fragment. _Nat. Commun._ 9, 3169 (2018). ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Cruz-Migoni, A. et al. Structure-based development of new RAS-effector inhibitors from a combination of active and inactive RAS-binding compounds. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 116,

2545–2550 (2019). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * McCarthy, M. J. et al. Discovery of high-affinity noncovalent allosteric KRAS inhibitors that disrupt effector binding. _ACS Omega_ 4,

2921–2930 (2019). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bery, N. et al. BRET-based RAS biosensors that show a novel small molecule is an inhibitor of RAS-effector protein-protein

interactions. _eLife_ 7, e37122 (2018). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kessler, D. et al. Drugging an undruggable pocket on KRAS. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 116, 15823–15829

(2019). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Canon, J. et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. _Nature_ 575, 217–223 (2019). ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

* Hallin, J. et al. The KRAS(G12C) inhibitor MRTX849 provides insight toward therapeutic susceptibility of KRAS-mutant cancers in mouse models and patients. _Cancer Discov._ 10, 54–71

(2019). PubMed Google Scholar * Janes, M. R. et al. Targeting KRAS mutant cancers with a covalent G12C-specific inhibitor. _Cell_ 172, 578–589 (2018). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lito,

P., Solomon, M., Li, L. S., Hansen, R. & Rosen, N. Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. _Science_ 351, 604–608 (2016). ADS CAS PubMed PubMed

Central Google Scholar * Ostrem, J. M., Peters, U., Sos, M. L., Wells, J. A. & Shokat, K. M. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions.

_Nature_ 503, 548–551 (2013). ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Patricelli, M. P. et al. Selective inhibition of oncogenic KRAS output with small molecules targeting the

inactive state. _Cancer Discov._ 6, 316–329 (2016). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fell, J. B. et al. Identification of the clinical development candidate MRTX849, a covalent KRAS(G12C)

inhibitor for the treatment of cancer. _J. Med. Chem._ https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b02052 (2020). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Lanman, B. A. et al. Discovery of a covalent

inhibitor of KRAS(G12C) (AMG 510) for the treatment of solid tumors. _J. Med. Chem._ 63, 52–65 (2020). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * McCormick, F. Sticking it to KRAS: covalent inhibitors

enter the clinic. _Cancer Cell_ 37, 3–4 (2020). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Xue, J. Y. et al. Rapid non-uniform adaptation to conformation-specific KRAS(G12C) inhibition. _Nature_ 577,

421–425 (2020). ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tanaka, T. & Rabbitts, T. H. Interfering with RAS-effector protein interactions prevent RAS-dependent tumour initiation and causes

stop-start control of cancer growth. _Oncogene_ 29, 6064–6070 (2010). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lobato, M. N. & Rabbitts, T. H. Intracellular antibodies and challenges facing their

use as therapeutic agents. _Trends Mol. Med._ 9, 390–396 (2003). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Melchionna, T. & Cattaneo, A. A protein silencing switch by ligand-induced

proteasome-targeting intrabodies. _J. Mol. Biol._ 374, 641–654 (2007). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bery, N. et al. A targeted protein degradation cell-based screening for nanobodies

selective toward the cellular RHOB GTP-bound conformation. _Cell Chem. Biol._ 26, 1544–1558 e1546 (2019). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Caussinus, E., Kanca, O. & Affolter, M.

Fluorescent fusion protein knockout mediated by anti-GFP nanobody. _Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol._ 19, 117–121 (2011). PubMed Google Scholar * Fulcher, L. J. et al. An affinity-directed protein

missile system for targeted proteolysis. _Open Biol_. 6, 160255 (2016). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Moutel, S. et al. NaLi-H1: a universal synthetic library of humanized

nanobodies providing highly functional antibodies and intrabodies. _eLife_ 5, e16228 (2016). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Portnoff, A. D., Stephens, E. A., Varner, J. D. &

DeLisa, M. P. Ubiquibodies, synthetic E3 ubiquitin ligases endowed with unnatural substrate specificity for targeted protein silencing. _J. Biol. Chem._ 289, 7844–7855 (2014). CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fulcher, L. J., Hutchinson, L. D., Macartney, T. J., Turnbull, C. & Sapkota, G. P. Targeting endogenous proteins for degradation through the

affinity-directed protein missile system. _Open Biol._ 7, 170066 (2017). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Sakamoto, K. M. et al. Protacs: chimeric molecules that target proteins to

the Skp1-Cullin-F box complex for ubiquitination and degradation. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 98, 8554–8559 (2001). ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Burslem, G. M. & Crews, C. M.

Proteolysis-targeting chimeras as therapeutics and tools for biological discovery. _Cell_ 181, 102–114 (2020). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Burslem, G. M. et al. The advantages of targeted

protein degradation over inhibition: an RTK case study. _Cell Chem. Biol._ 25, 67–77 (2018). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pettersson, M. & Crews, C. M. PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras

(PROTACs)—past, present and future. _Drug Discov. Today Technol._ 31, 15–27 (2019). PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Li, Z. et al. Development and characterization of a Wee1 kinase

degrader. _Cell Chem. Biol._ 27, 57–65 (2020). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * You, I. et al. Discovery of an AKT degrader with prolonged inhibition of downstream signaling. _Cell Chem.

Biol._ 27, 66–73 (2020). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * de Wispelaere, M. et al. Small molecule degraders of the hepatitis C virus protease reduce susceptibility to resistance mutations.

_Nat. Commun._ 10, 3468 (2019). ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Cromm, P. M., Samarasinghe, K. T. G., Hines, J. & Crews, C. M. Addressing kinase-independent functions of

Fak via PROTAC-mediated degradation. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 140, 17019–17026 (2018). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Raina, K. et al. PROTAC-induced BET protein degradation as a therapy for

castration-resistant prostate cancer. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 113, 7124–7129 (2016). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tovell, H. et al. Design and characterization of SGK3-PROTAC1, an

isoform specific SGK3 kinase PROTAC degrader. _ACS Chem. Biol._ 14, 2024–2034 (2019). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Farnaby, W. et al. BAF complex vulnerabilities in cancer

demonstrated via structure-based PROTAC design. _Nat. Chem. Biol._ 15, 672–680 (2019). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Bai, L. et al. A potent and selective small-molecule

degrader of STAT3 achieves complete tumor regression in vivo. _Cancer Cell_ 36, 498–511 (2019). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zeng, M. et al. Exploring targeted degradation strategy for

oncogenic KRAS(G12C). _Cell Chem. Biol._ 27, 19–31 (2019). PubMed Google Scholar * Tanaka, T. & Rabbitts, T. H. Intrabodies based on intracellular capture frameworks that bind the RAS

protein with high affinity and impair oncogenic transformation. _EMBO J._ 22, 1025–1035 (2003). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tanaka, T., Sewell, H., Waters, S., Phillips,

S. E. & Rabbitts, T. H. Single domain intracellular antibodies from diverse libraries: emphasizing dual functions of LMO2 protein interactions using a single VH domain. _J. Biol. Chem._

286, 3707–3716 (2011). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Meng, L. et al. Epoxomicin, a potent and selective proteasome inhibitor, exhibits in vivo antiinflammatory activity. _Proc. Natl Acad.

Sci. USA_ 96, 10403–10408 (1999). ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Olson, C. M. et al. Pharmacological perturbation of CDK9 using selective CDK9 inhibition or degradation. _Nat. Chem.

Biol._ 14, 163–170 (2018). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bondeson, D. P. et al. Lessons in PROTAC design from selective degradation with a promiscuous warhead. _Cell Chem. Biol._ 25, 78–87

(2018). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Nowak, R. P. et al. Plasticity in binding confers selectivity in ligand-induced protein degradation. _Nat. Chem. Biol._ 14, 706–714 (2018). CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Singh, A. et al. A gene expression signature associated with “K-Ras addiction” reveals regulators of EMT and tumor cell survival. _Cancer Cell_ 15,

489–500 (2009). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kazi, A. et al. GSK3 suppression upregulates beta-catenin and c-Myc to abrogate KRas-dependent tumors. _Nat. Commun._ 9, 5154

(2018). ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tse, E. & Rabbitts, T. H. Intracellular antibody-caspase-mediated cell killing: an approach for application in cancer therapy.

_Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 97, 12266–12271 (2000). ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chambers, J. S., Brend, T. & Rabbitts, T. H. Cancer cell killing by target antigen engagement with

engineered complementary intracellular antibody single domains fused to pro-caspase3. _Sci. Rep._ 9, 8553 (2019). ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Röth, S., Macartney, T. J.,

Konopacka, A., Queisser, M. A. & Sapkota, G. P. Targeting endogenous K-RAS for degradation through the affinity-directed protein missile system. Preprint at

https://doi.org/10.1101/805150v1 (2019). * Drosten, M. et al. Genetic analysis of Ras signalling pathways in cell proliferation, migration and survival. _EMBO J._ 29, 1091–1104 (2010). CAS

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Zhang, J., Shrivastava, S., Cleveland, R. O. & Rabbitts, T. H. Lipid-mRNA nanoparticle designed to enhance intracellular delivery mediated by

shock waves. _ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces_ 11, 10481–10491 (2019). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Stewart, M. P. et al. In vitro and ex vivo strategies for intracellular

delivery. _Nature_ 538, 183–192 (2016). ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Bery, N. & Rabbitts, T. H. Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer 2 (BRET2)-based RAS biosensors to

characterize RAS inhibitors. _Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol_. 83, e83 (2019). PubMed Google Scholar * Barger, C. J., Branick, C., Chee, L. & Karpf, A. R. Pan-cancer analyses reveal genomic

features of FOXM1 overexpression in cancer. _Cancers_ 11, 251 (2019). CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Grant numbers Wellcome Trust Award

099246/Z/12/Z; Bloodwise grant 12051; MRC MR/J000612/1. We would like to thank Dr. Remco Prevo and Prof. Geoff Higgins for T24, H1299 and MRC5 cells. We acknowledge the expert technical help

from Dr. Hedia Chagraoui for the qPCR experiments and analysis and Dr. Alex Martin and Prof. Robert Carlisle for access to the IVIS instrument and help with its operation. We also like to

thank Roo Bhasin and Jonathon Merrill for excellent technical help with the mouse experiments. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * Nicolas Bery Present address: Cancer Research Centre of

Toulouse, INSERM - Université Toulouse III Paul Sabatier - CNRS, 2 avenue Hubert Curien, Toulouse, 31037, France * Ami Miller & Terry Rabbitts Present address: Institute of Cancer

Research, Division of Cancer Therapeutics, 15 Cotswold Road, Sutton, London, SM2 5NG, UK AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, MRC Molecular Haematology

Unit, University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, OX3 9DS, UK Nicolas Bery, Ami Miller & Terry Rabbitts Authors * Nicolas Bery View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ami Miller View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Terry Rabbitts View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Originators of project: N.B. and T.R. Participated in research design: N.B. and T.R. Conducted experiments: N.B. and A.M.

Performed data analysis: N.B., A.M. and T.R. Wrote or contributed to the writing of the paper: all authors. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Terry Rabbitts. ETHICS DECLARATIONS

COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PEER REVIEW INFORMATION _Nature Communications_ thanks Alessio Ciulli and the other, anonymous,

reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available. PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE REPORTING SUMMARY SOURCE DATA SOURCE DATA RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN

ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format,

as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third

party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright

holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Bery, N., Miller, A. & Rabbitts,

T. A potent KRAS macromolecule degrader specifically targeting tumours with mutant KRAS. _Nat Commun_ 11, 3233 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17022-w Download citation *

Received: 12 March 2020 * Accepted: 29 May 2020 * Published: 26 June 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17022-w SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will

be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative