- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists around the globe have been working resolutely to find therapies to treat patients and avert the spreading of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In this commentary,

we highlight some of the latest studies that provide atomic-resolution structural details imperative for the development of vaccines and antiviral therapeutics. Severe acute respiratory

syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has emerged as a novel rapidly spreading human pathogen that causes severe respiratory distress and pneumonia—coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)1. This

is the third outbreak in recent years caused by emerging coronaviruses after spread of SARS-CoV in 2002 and MERS-CoV in 2012. SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV are closely related and have similar

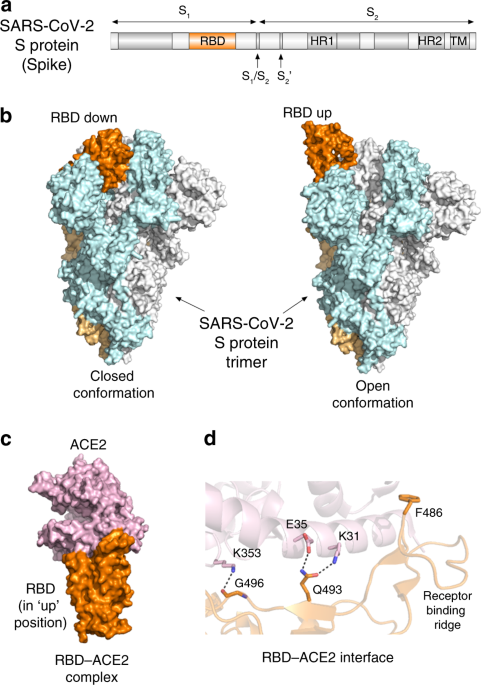

genomes and mechanisms for entry into host cells. The coronavirus spike glycoprotein (S protein), which protrudes from the virion surface, plays a pivotal role in initiating the viral

infection facilitating coronavirus attachment to the host cell surface receptor and fusion of viral and host cell membranes. The spike protein consists of two functional subunits, S1 and S2

(Fig. 1a), and the receptor-binding domain (RBD) resides within the S1 subunit. The RBD of the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binds to the peptidase domain of angiotensin-converting

enzyme 2 (ACE2), initiating virus attachment to the host cell surface. The S2 subunit mediates virus-host membrane fusion, which requires S protein proteolytic cleavage between the S1 and S2

subunits and additionally at another, a so called S2′ site by host proteases. Owing to its crucial role in viral infection, the spike protein has been a major target for antibody-mediated

neutralization of SARS-CoV. Despite high-sequence similarity between the spike proteins of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, new studies with recovered SARS and COVID-19 patients sera show limited

cross-neutralization2,3, implying that recovery from one infection may not protect against another3, and that the development of vaccines and therapeutics specific to COVID-19 is needed to

combat this disease. In that regard, a number of approaches have already been taken and some show promising results. These include the design of new drugs and evaluation of existing

therapeutics used individually or in combination, production of antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, particularly its RBD, and targeting other viral and host cell proteins

essential for survival and replication of the virus. Recently published structural studies of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein shed light on the molecular mechanism by which its RBD recognizes

human ACE2 and provide an invaluable knowledge in guiding the development of vaccines and inhibitors of viral entry2,4,5,6,7. Wrapp et al. and Walls et al. report cryo-EM structures of the

homotrimeric SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in a prefusion state2,4 (Fig. 1b). The data from Walls et al. show that the spike protein exists in two conformations, which is also observed in the

other coronaviruses4. In the closed conformation, all three RBDs are buried at the interface between three protomers, whereas in the open conformation one of RBDs rotates up and therefore is

primed for binding to ACE2. In addition, Wrapp et al. demonstrate that the open conformation represents a predominant state of the spike protein trimer2. How does RBD of the SARS-CoV-2

spike protein binds to the human receptor ACE2? The studies by Shang et al., Lan et al., and Yan et al. illuminate the atomic-resolution details of this interaction5,6,7 (Fig. 1c). Of note,

ACE2 normally functions to promote the maturation of angiotensin hormone which controls blood pressure. Aberrant ACE2 levels have been linked to cardiovascular diseases8 and may play a role

in disease severity observed in COVID-19 patients with comorbid conditions, such as heart, blood, and lung diseases and diabetes. Yan et al. describe a cryo-EM structure of the complex of

full length human ACE2 with RBD from the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and suggest that two spike protein trimers can simultaneously bind to an ACE2 dimer7. The precise binding interface of the

SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and ACE2 can be dissected from the crystal structures of the complex determined by Shang et al. and Lan et al5,6 (Fig. 1d). Analyzing the structure, Shang et al.

uncovered several hotspots that distinguish binding of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV5. The authors found that overall, the RBD-ACE2 interface in the SARS-CoV-2 complex is larger than the binding

interface in the SARS-CoV complex. RBD of SARS-CoV-2 forms more contacts with ACE2, including three additional intermolecular salt bridges, involving Q493 and G496 of RBD and K31, E35, and

K353 of ACE2 (dashed lines in Fig. 1d). The receptor-binding ridge of RBD in the SARS-CoV-2 complex adopts a more compact conformation, allowing an adjacent loop to move closer to ACE2 and

F486 of RBD to insert in the hydrophobic pocket of ACE2. These structural differences could account for the 4- to 20-fold increase in binding affinity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD toward ACE2

compared to that of SARS-CoV, which was observed independently by several groups2,4,5,6. Analysis of the crystal structures of RBD from the SARS-CoV spike protein in complex with

established SARS-CoV neutralizing human m396 and 80R antibodies reveals that the antibodies are bound in the same binding site as ACE29,10, implying that their neutralizing mechanism is a

direct blockage of receptor binding. Lan et al. estimate that 7 out of 21 epitope residues for m396 and 16 out of 25 epitope residues for 80R are not conserved in RBD sequences of SARS-CoV

and SARS-CoV-2, which may explain the lack of appreciable cross-reactivity for these antibodies6. Interestingly, a recent structure of RBD from the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein bound to another

antibody isolated from a SARS patient, CR3022, determined by Yuan et al. shows that CR3022 targets an epitope distal from the ACE2-binding site, which may provide some cross-reactivity that

needs to be thoroughly evaluated11. What are other therapeutic targets beyond the receptor-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein? Proteolytic cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 spike

protein by the human serine protease TMPRSS2 is a critical step in the virus entry through the plasma membrane fusion mechanism (Fig. 2), as shown by Hoffmann et al.12. The authors

demonstrate that camostat mesylate, a clinically proven serine protease inhibitor that halts TMPRSS2 activity, blocks SARS-CoV-2 infection of lung cells12. Following binding to ACE2 and

disassociation of the ACE2-bound S1 subunit, the S2 subunit of the spike protein—still attached to the virus envelope through its C-terminal transmembrane domain and additionally cleaved at

the S2′ site—inserts the cleaved terminus into the host cell plasma membrane and thus physically links both viral and cell membranes. This allows the heptad repeats (HR1 and HR2) of the S2

subunit to interact and assemble into a six-helix bundle, which is needed to bring the membranes closer to each other for final fusion. Xia et al. now show that EK1C4, a lipopeptide that

targets heptad repeats, is a potent inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 fusion in cellular assays and in a mouse model13. By using human clinical-grade recombinant soluble ACE2, Monteil et al. reduced

SARS-CoV-2 viral growth by over 103-fold in Vero cells and suppressed infection in engineered human blood vessel organoids and kidney organoids14. In addition to targeting components of the

viral attachment and the membrane fusion machinery, other strategies to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 include impeding virus entry into the host cell through the endosomal pathway and disrupting

activities of viral proteins. Ou et al. found that SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-virions enter cells mainly through endocytosis and that inhibition of the proteins essential in the endosomal signaling,

such as PIKfyve, TPC2, or cathepsin L by apilimod, tetrandrine, or SID 26681509, respectively, reduces host cell entry3. Once inside the host cell, viral RNA uses the host ribosomal

machinery to produce important for its own life cycle proteins that also serve as attractive targets for the development of anti-SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics. One of such proteins is the

SARS-CoV-2 main protease Mpro, which is required for processing the polyproteins translated from the viral RNA. Inhibition of the Mpro activity impedes viral replication, and the crystal

structure of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro in complex with the α-ketoamide inhibitor provides the mechanistic details necessary to advance in this direction15. The speed by which structural

information on the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been collected is astonishing. Structural approaches will likely contribute to drug discoveries and validation and aid in the development of vaccines

to reduce and eventually eliminate the ongoing public health emergency. REFERENCES * Wu, F. et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. _Nature_ 579, 265–269

(2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wrapp, D. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. _Science_ 367, 1260–1263 (2020). Article ADS CAS Google

Scholar * Ou, X. et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. _Nat. Commun._ 11, 1620 (2020). Article CAS

Google Scholar * Walls, A. C. et al. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. _Cell_ 181, 281–292 e286 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Shang, J.

et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. _Nature_ 581, 221–224 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Lan, J. et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding

domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. _Nature_ 581, 215–220 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yan, R. et al. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2.

_Science_ 367, 1444–1448 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Patel, V. B., Zhong, J. C., Grant, M. B. & Oudit, G. Y. Role of the ACE2/Angiotensin 1-7 axis of the renin-angiotensin

system in heart failure. _Circ. Res._ 118, 1313–1326 (2016). Article CAS Google Scholar * Prabakaran, P. et al. Structure of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor-binding

domain complexed with neutralizing antibody. _J. Biol. Chem._ 281, 15829–15836 (2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hwang, W. C. et al. Structural basis of neutralization by a human

anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome spike protein antibody, 80R. _J. Biol. Chem._ 281, 34610–34616 (2006). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yuan, M. et al. A highly conserved cryptic

epitope in the receptor-binding domains of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. _Science_ 368, 630–633 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hoffmann, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2

and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. _Cell_ 181, 271–280 e278 (2020). Article CAS Google Scholar * Xia, S. et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously

2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. _Cell Res._ 30, 343–355 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Monteil, V. et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infections in engineered human tissues using clinical-grade soluble human ACE2. _Cell_ 181, 905–913.e7 (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Zhang, L. et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved alpha-ketoamide inhibitors. _Science_ 368, 409–412

(2020). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research in the Kutateladze laboratory is funded by the NIH. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND

AFFILIATIONS * Department of Pharmacology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, 80045, USA Yi Zhang & Tatiana G. Kutateladze Authors * Yi Zhang View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tatiana G. Kutateladze View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Y.Z.

and T.G.K. contributed to the writing of this manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Tatiana G. Kutateladze. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no

competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND

PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any

medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The

images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not

included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly

from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Zhang, Y.,

Kutateladze, T.G. Molecular structure analyses suggest strategies to therapeutically target SARS-CoV-2. _Nat Commun_ 11, 2920 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16779-4 Download

citation * Received: 13 April 2020 * Accepted: 18 May 2020 * Published: 10 June 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16779-4 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link

with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative