- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Synthetic skills are the prerequisite and foundation for the modern chemical and pharmaceutical industry. The same is true for nanotechnology, whose development has been hindered by

the sluggish advance of its synthetic toolbox, i.e., the emerging field of nanosynthesis. Unlike organic chemistry, where the variety of functional groups provides numerous handles for

designing chemical selectivity, colloidal particles have only facets and ligands. Such handles are similar in reactivity to each other, limited in type, symmetrically positioned, and

difficult to control. In this work, we demonstrate the use of polymer shells as adjustable masks for nanosynthesis, where the different modes of shell transformation allow unconventional

designs beyond facet control. In contrast to ligands, which bind dynamically and individually, the polymer masks are firmly attached as sizeable patches but at the same time are easy to

manipulate, allowing versatile and multi-step functionalization of colloidal particles at selective locations. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS TOTAL SYNTHESIS OF COLLOIDAL MATTER

Article 02 June 2021 SELF-REGULATED CO-ASSEMBLY OF SOFT AND HARD NANOPARTICLES Article Open access 28 September 2021 PARTICLE ENGINEERING ENABLED BY POLYPHENOL-MEDIATED SUPRAMOLECULAR

NETWORKS Article Open access 23 September 2020 INTRODUCTION The emerging field of nanosynthesis focuses on the development of synthetic skills at the nanoscale1,2,3,4,5,6. One major

bottleneck at the moment is the design of chemical selectivity on nanoparticles. Unlike organic compounds with distinct functional groups, colloidal particles have only facets and ligands,

which are highly inter-dependent, as many facets only exist in the presence of specific ligands. This complexity makes it extremely difficult to manipulate them as synthetic handles, more

specifically for the following reasons. Firstly, there is no method available to control the area, shape, and position of ligand patches7. While facet-specific functionalization of Au

nanorods (AuNRs) has been achieved8,9,10, controlling ligand patches beyond facets remains a major challenge. Secondly, the ligands are never permanent—they dynamically bind and dissociate

from the nanoparticle surface, even for the strongest thiol ligands on Au/Ag surfaces11. Hence, some degree of mixing is inevitable. Thirdly, the colloidal instability of nanoparticles is a

constant nuisance, which not only narrows the choice of ligands but also poses massive uncertainties in any exploration attempts. Decorating nanoparticles with single12 and multiple island

domains1,13,14 have been achieved, but efforts of exploiting such islands as synthetic masks were still rudimentary9,15,16. While the structural simplicity is one reason, a more important

reason is that the island masks are stationary and only variable from the synthesis. Hence, their regio-selective role can only be exploited once. Much can be desired if the mask is

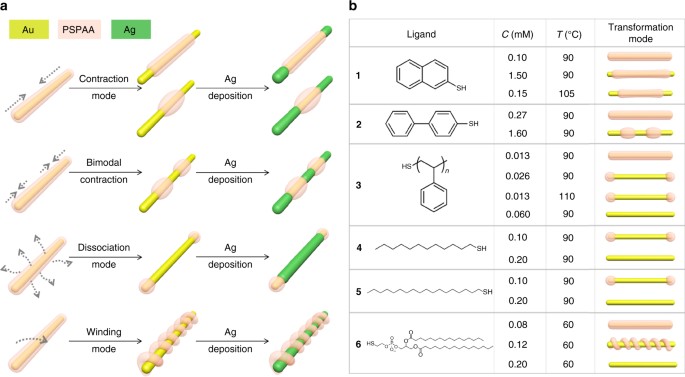

adjustable for multi-step regio-selective reactions. Herein, we demonstrate that polymer shells on nanorods can undergo different modes of shell transformation, allowing then to act as

versatile synthetic handles beyond facet control. The polymer shells are highly resistant to aggregation but at the same time fluidic and adjustable, an essential feature for achieving

site-selectivity in multi-step nanosynthesis. RESULTS CONCEPT The critical issue is to find a stable but fluid mask that can be precisely manipulated, so that the encapsulated nanoparticles

can be selectively exposed and functionalized. Here, different structures are derived from heat-induced transformation of polystyrene- block-poly(acrylic acid) (PSPAA) shells, which are

created by a general method of nanoparticle encapsulation17. The PSPAA-coated nanoparticles are known to be extremely stable, even in saturated salt solutions18. To start, AuNRs were mixed

with the amphiphilic PSPAA and a hydrophobic ligand (1–6, Fig. 1) in dimethyl formamide (DMF)/H2O mixture (4.5:1 V/V), and then heated at 110 °C for 2 h, giving core-shell structures

((AuNR-ligand)@PSPAA, Supplementary Figs. 1–5). Basically, the PSPAA self-assembles on the hydrophobically functionalized nanoparticle surface, with PS blocks facing inward and the PAA

blocks dissolved in the solvent. These nanoparticles were purified repeatedly to remove DMF and the excess ligand, and then dispersed in water. To our great interest, simple heating can

transform the resulting PSPAA shells in different modes (contraction, bimodal contraction, dissociation, and winding), depending on the choice of ligand and their concentration in the

initial encapsulation step. TRANSFORMATION MODES For (AuNR-1)@PSPAA, heating in water caused contraction of the polymer domain, and its degree can be precisely controlled by adjusting the

temperature and duration of this step. At 105 °C over 1.5–4 h, the polymer domain slowly contracts (Fig. 2b–d), gradually exposing the AuNRs from the ends and revealing increasing area of

the side facets (6 ± 2%, 12 ± 4%, and 27 ± 3%, see Fig. 2r). The polymer appears to be stuck at this stage, as longer heating (105 °C for 6 h) does not cause further exposure. Only with

harsher conditions, we managed to expose 45 ± 5% (110 °C for 3 h, Fig. 2e) and 68 ± 5% of the side facets (115 °C for 3 h, Fig. 2f, g). Large-view scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of

the sample 1c (Fig. 2h) and TEM image of the sample 1 f (Fig. 2i) demonstrate the purity of the typical samples, and the structure was further supported by atomic force microscope (AFM)

line scan (Fig. 2q). It appears that the high temperatures also caused significant dissociation of the shells, leading to reduced volume of the polymer domain. On the other hand, at lower

temperature of 90 °C, the contraction was just enough to expose the tips of the AuNRs, but the progress was barely noticeable even after 12 h (Supplementary Fig. 6). The partial polymer

shells on these exposed AuNRs are highly uniform in terms of the extent of contraction and the equal distance from the two ends (Fig. 2h, i, r and Supplementary Figs. 7–12). Figure 2b

appears similar to the facet-specific functionalization in the literature8,9, but the subsequent structures offer a unique ability to gradually expose the side facets of the AuNRs (Fig.

2b–f), going beyond facet specificity. The contraction of the PSPAA shell is found to be shape-dependent. For Au nanospheres (AuNSs), even the harshest condition (115 °C for 3 h) did not

cause exposure of the Au surface in (AuNS-1)@PSPAA (Supplementary Fig. 13). We speculate that the PSPAA shell above its glass transition temperature (100 °C for bulk PS)19 may behave like a

viscous liquid as the gradual de-wetting exposes the high curvature ends. More specifically, withdrawing the spindle-like shells of (AuNR-1)@PSPAA is favorable in terms of reducing the

PS-water interface, but the shell on (AuNS-1)@PSPAA is already spherical. Breaking it would initially cause a dramatic increase of the interface. Indeed, the surface tension of the PSPAA

shell on AuNRs is evident even in the core-shell stage before the contraction (Fig. 2a), where the shell at the tips is much thinner than that covering the sides. Interestingly, ligand 2 led

to a bimodal contraction mode. When the (AuNR-2)@PSPAA (Fig. 2j) were heated in water at 90 °C, the polymer shell first contracted to expose the two tips (3 h, Fig. 2k). Then, the two

polymer ends got stuck after this stage and the middle section of the polymer shell became stretched and thinner (Fig. 2l). These behaviors were similar to the above case. However, with

longer heating, a break-up point is reached (Fig. 2m, o) and the polymer shell split into two segments, which contracted further from the middle (6 h, Fig. 2n, p). The bimodal contraction is

uniform and reproducible, and it depends on the initial ligand concentration (1.6 mM) at the encapsulation step. When less ligand (0.27 mM) was used, the polymer shell showed minimal

contraction even after 6 h at 90 °C (Supplementary Fig. 14). We estimated that completely covering all Au surface in our experiments would require only 0.2 μM ligand and hence, the ligands

used were in large excess. Considering that free ligands in solution would have been completely removed during purification, they would have no effect in the shell contraction step. The only

way is via the excess ligands remained in the shell20, likely as a plasticizer21 improving the liquidity of the polymer (vide infra). The high percentage of the products with bimodal

contraction is intriguing. The different parts of the polymer shell are expected to have similar liquidity under the same reaction conditions. However, the two ends of the polymer section

after the initial contraction (exposing the tips) cannot move further, whereas the middle section still can. On this basis, we hypothesize that the ligand 2 may migrate on the Au surface

along with the contracting polymer shell and became denser, preventing further movement of the shell (Fig. 2s). This hypothesis is consistent with (1) the expectation that the hydrophobic

ligand should be retained within the hydrophobic polymer domain; (2) the colloidal stability of the contracted particles in water, suggesting the hydrophilic exposed surface; (3) the fact

that Ag and Pd can be readily deposited on the exposed Au surface without ligand exchange (vide infra). When ligand 3 was used, a dissociation mode was observed: most of the polymer shell on

(AuNR-3)@PSPAA disappeared after heating in water at 90 °C for 3 h, leaving behind only two caps on the tips of the AuNRs (Fig. 3a, b). The extent of polymer dissociation depends on the

ligand concentration (0.026 mM) during the initial encapsulation step. With higher ligand concentration (0.06 mM), the polymer shell completely disappeared after 3 h at 90 °C (Supplementary

Fig. 15). At a lower concentration (0.013 mM), 90 °C heating had little effects (Supplementary Fig. 16), and harsher conditions (105 °C for 3 h) were necessary to achieve the structure of

Fig. 3b (Supplementary Fig. 17). Most interestingly, the use of amphiphilic ligand 6 led to helical polymer domains after the shell transformation (the winding mode, Fig. 3d, e, h, and

Supplementary Fig. 18). For the (AuNR-6)@PSPAA, the shell dissociation was easier than the above cases and hence the heating was carried out at only 60 °C for 3 h. The concentration of

ligand 6 during the encapsulation step was critical: At 0.12 mM, the polymer domain partially dissociated and the remaining polymer became a helical cylinder winding around the AuNRs

(Supplementary Fig. 18). At higher ligand concentration (>0.2 mM), most of the polymer shell disappeared after the heating (Supplementary Fig. 19); at lower concentration (0.08 mM),

neither dissociation nor transformation was observed (Supplementary Fig. 20). This winding mode can be also achieved on short AuNRs (_l_ = 76 ± 3 nm, Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 21),

where the remaining polymer domain appeared dissymmetrical after heating in water, suggesting similar winding mode. For ligands 1–3, the winding mode cannot be achieved despite repeated

trials with varying ligand concentration and heating temperature. DETERMINING FACTORS The reaction conditions leading to the four transformation modes are summarized in Fig. 1 (see greater

details in Supplementary Fig. 22). Several general trends can be recognized: (1) when the ligand concentration or temperature is below threshold, the polymer transformation cannot occur; (2)

excess ligand and high temperature are complimentary in promoting transformation; and 3) when allowed, the transformation is more extensive with longer incubation time. Among the ligands, 1

appears to be the strongest. The contraction of the polymer shell with ligand 1 is independent of the initial ligand concentration and higher temperatures are necessary. We speculate that

the strong π–π interaction among the aromatic ligands might be responsible. Ligand 2 would be similar to ligand 1 in terms of close packing, except that the twisted conformation of the

biphenyl rings would partially compromise the stability of the resulting patches. Indeed, bimodal contraction can also be achieved with (AuNR-1)@PSPAA, except that harsher conditions (120 °C

for 6 h) are necessary and the yield was much lower (<10%) as compared to (AuNR-2)@PSPAA. In comparison, the polymeric ligand 3 would be too bulky to pack well on the Au surface,

facilitating the polymer shell dissociation. The polymer cap at the tips of AuNR has a high contact area with Au per unit volume of polymer, allowing it to persist longer than the shell on

the flat facets. To further investigate the effects of ligand packing, we tried to use 4 and 5 as ligand. At 0.10 mM, the dissociation mode was observed (90 °C for 3 h, Supplementary Fig.

23), and at 0.20 mM all polymer shell was completely lost (Supplementary Fig. 24). It appears that these ligands without π–π interaction dissociate more readily from the Au surface22.

Considering the lowest temperature of transformation, ligand 6 appears to be the weakest. It is important to note its amphiphilicity—having ionic and polar functionalities underneath the

hydrophobic PS layer may cause the ligand to be less stable, or more mobile. Importantly, with 6 at the Au-PS interface and the tethered PAA blocks at the PS-water interface, the polymer

domain is enclosed by surfactants. As such, it is a micelle, except that it adsorbs on the Au surface with the thiol ends, as opposed to the conventional micelles freely suspended in

solution. Transforming the polymer shell into a winding cylinder is not favorable in terms of reducing the PS solvent or Au-PS interface. It appears that the polymer domain prefers a

cylindrical shape driven by the micelle properties5,19, and the resulting cylinder would be longer than the length of the AuNR, forcing it to wind around. The chiral mechanism is similar to

the insertion of a wire into a cylinder, where the confined environment forces the initial tilting and a helical shape ensues as a result of energy minimization, because forming sharp kinks

is more costly than smooth winding23. Similarly, the polymer cylinder confined on the surface of the AuNR has to randomly tilt at one direction, and the remaining cylinder would wind around

following the same direction. On these bases, we summarize the determining factors in Fig. 4. The polymer liquidity appears to be a prerequisite, without it the ligands cannot exert

influence as they are locked at their original place by the glassy polymer. It is known that low-molecular-weight molecules such as solvents and ligands can dissolve in the PS domain, where

the former is known as the swelling agent and the latter as plasticizer21. These molecules form secondary bonds (van der Waals interactions, and so on) with the PS chains and spread them

apart. Thus, they weaken the PS–PS interactions and provide more mobility for the PS domain, resulting in a softer mass with a lower glass transition temperature. Hence, both high

temperature and high ligand concentration can improve polymer liquidity and they are complimentary in promoting shell transformation. Only with sufficient polymer liquidity, the incubation

time would have effects and the same is true for the ligands. Ligands with strong π–π interaction are more difficult to dissociate and probably also interact with PS chains better, allowing

them to persist on the Au surface and leading to the contraction modes. Aliphatic and bulky ligands would dissociate upon heating, causing the entire polymer patches to dislodge and move

into the aqueous phase as free micelles. On the other hand, amphiphilic ligand can cause the polymer domain to be micelle-like, leading to winding cylinders. In short, ligand is the critical

factor determining the modes of shell transformation, whereas excess ligand, high temperature, and time affect polymer liquidity. MASKS FOR COLLOIDAL NANOSYNTHESIS The partially exposed

AuNRs provide a versatile platform for further functionalization, where the distinct Au and PSPAA surfaces can be exploited for chemical selectivity. As a demonstration, we deposited Ag on

the above masked AuNRs. In a typical synthesis, the masked AuNRs were purified from the preparative solution, without further ligand exchange. They were mixed with the reductant

hydroquinone, followed by AgNO3, so that the resulting Ag atoms can be deposited on the AuNRs. For all of the four masked structures discussed above, Ag was selectively deposited on the

exposed Au surface, judged by the obvious thickening at the corresponding segments (Fig. 2t–x, Fig. 3c, f, and Supplementary Figs. 25–32). There was no Ag deposited on the PSPAA surface.

Figure 2y shows the AuNRs with bimodal contraction after growing Ag, giving Ag-Au-Ag-Au-Ag penta-block structure. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mapping in Fig. 2z confirms the

selective deposition of Ag. The most important aspect of continual contraction is to exploit the different stages for chemical selectivity of multi-step reactions. As a proof-of-concept, we

coated Pd on the exposed Au surface and then induced further contraction of the polymer. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, the second step contraction revealed a small gap of Au surface between the

Pd-coated and the PSPAA-coated domains, where Ag can be selectively deposited. Specifically, the reduction of Na2PdCl4 by hydroquinone led to a conformal coating on the exposed Au surface24

and a layer of fine particles on the PSPAA shell (Fig. 5b–e). The latter made the PSPAA shell appear dirty and gave rise to a smeared Pd region in the EDX mapping (Fig. 5d). After the

second contraction, we performed Ag deposition by reacting AgNO3 with hydroquinone, and obtained a structure that resembles a blot with two nuts (Fig. 5f). The selective thickening at the

neck position of all of the AuNRs implies the success of our synthetic strategy, likely because Ag has matching lattice with Au, but is mismatched with Pd25. The Ag domain was confirmed by

EDX mapping as shown in Fig. 5e. When AuNRs with longer exposed segments (similar to Fig. 2d) were used in step 1, the thickened neck position appeared closer to the center (Fig. 5g) as

expected. To the best of our knowledge, selective deposition at arbitrary location on AuNRs has not been achieved to date. The highly predictable nature of the PSPAA shell transformation

allows rational design of multi-step, regio-selective chemical reactions. PAA can be embedded within inorganic domains (Au, PbTiO3, Fe3O4, CdSe, and so on) so that PAA-based molecules can

serve as template for the growth of inorganic nanoparticles26. This capability can be attributed to the interaction of PAA with metal ions through the –COOH groups. In our system, we choose

conditions so as to avoid metal deposition (Ag and Pd) on the PAA surface. Since the metal–metal bonds are in general stronger than the –COO-metal interaction, it would be possible to

suppress the metal nucleation on the –COOH surface by competition. In other words, metal can be selectively deposited on the exposed metal surface, rather than the PAA surface. Between Ag

and Pd, Ag atoms are better stabilized in solution than Pd atoms, and Pd has larger lattice mismatch with Au (meaning less effective Pd–Au bonds at the interface). Hence, Pd deposition is in

general less selective than Ag deposition in our system. Welding colloidal structures together is a major challenge in the field, as the crosslinking reagents would typically compromise the

colloidal stability of nanoparticles, but the surfactants introduced to solve the problem would compromise the effects of crosslinking. Considering the dilemma, the partially masked AuNRs

may lead to a breakthrough, as the partial PSPAA shell can prevent aggregation and the exposed tips can lead to selective points of contact. Specifically, we coated the (AuNR-1)@PSPAA with

Ag tips (similar to Fig. 2u). The product was dispersed in water, followed by the crosslinking reagent Na2S, and the mixture was kept at room temperature for 2 h. The Na2S caused the

nanorods to aggregate via the exposed tips, and then converted the Ag layer to Ag2S, crosslinking the nanorods in the process (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Figs. 33 and 34), which can be further

supported by the small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) results (Supplementary Fig. 35 and Supplementary Table 1). The inset in the Fig. 6b shows that the two exposed ends were embedded in a

single Ag2S nanocrystal. STEM image and corresponding EDX mapping confirmed the composition assignments (Fig. 6c, d). Thus, with PSPAA shells at the specific locations, the tip-to-tip

aggregation and the welding of the nanorods via Ag2S bridges can be readily carried out. In comparison, doing the same for hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-stabilized AuNRs

encountered significant hurdles of reagent compatibility because of the labile surfactant. We applied the polymer masks on Au nanoparticles with different shapes. As shown in Fig. 7, the

tips of Au bipyramid (Fig. 7a, and Supplementary Figs. 36–38) and triangular nanoprisms (Fig. 7b, and Supplementary Fig. 40) can be selectively exposed by contracting the PSPAA shells. With

the help of polymer masks, Ag can be selectively deposited on the exposed Au surface, giving two and three tips, respectively. Interestingly, gold bipyramid with single Ag tip (Supplementary

Fig. 38) can be obtained when the rate of Ag reduction was slow; and growth on both tips can be achieved (Supplementary Fig. 39) when the reduction was fast. This asymmetric Ag overgrowth

behavior can be explained by our previously reported depletion sphere mechanism14,27, where the slower build-up of Ag oversaturation can lead to a larger radius of depleted sphere of Ag

atoms, inhibiting growth at the other tip. DISCUSSION In conclusion, we exploit the multiple modes of PSPAA shell transformation for masked synthesis of colloidal nanorods. The

transformation modes are governed by the type of ligand and its concentration in the encapsulation step, provided that the polymer shell has sufficient liquidity. Unlike solid inorganic

shell, the pliable PSPAA shell can move and transform, so that its rich interaction with the underlying ligand layer can be fully exploited, leading to diverse structures. Moreover, the

gradual receding of the polymer shell gives multiple layers of reaction sites—an unprecedented synthetic capability with similar roles as the protecting groups in organic chemistry. The

polymer surface with long, ionic PAA chains renders the nanoparticles with great colloidal stability and a certain degree of inertness during metal deposition. The polymer masks are firmly

attached to the nanoparticles, so that there are few compatibility issues with the subsequent reagents used for metal deposition and crosslinking. With such a synthetic platform, new

colloidal syntheses can be designed, where the stable polymer patches and their predictable behavior are critical in realizing regio-selectivity and multi-step reactions. Our six-step

colloidal synthesis, including the synthesis of nanorods, encapsulation, contraction, Pd deposition, further contraction, and Ag deposition, is a powerful, though preliminary, demonstration

of colloidal synthetic designs. We believe that further exploitation of the pliable polymer masks can bring about a leap forward in sophisticated nanosynthesis. METHODS MATERIALS AND METHODS

All chemical reagents were used without further purification. Hydrogen tetrachloroaurate (III) hydrate 99.9% (metal basis Au 49%), 1-octadecanethiol (96%) and 1-dodecanethiol (98%) were

purchased from Alfa Aesar; sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate (99.0%), hydroquinone (99.5%), AgNO3 (99.9999%), 2-naphthalenethiol (99%), biphenyl-4-thiol (97%), hexadecyltrimethylammonium

bromide (99%), and cetyltrimethylammoniumchloride (CTAC, 99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; 1, 2 dipalmitoyl-_sn_-glycero-3-phosphothioethanol (sodium salt) was purchased from Avanti

Polar Lipids. Amphiphilic diblock copolymers polystyrene-_block_-poly (acrylic acid) (PS154-_b_-PAA49, _M_n = 16,000 for the PS block and _M_n = 3500 for the PAA block, _M_w/_M_n = 1.15) and

thiol-terminated polystyrene (PS-SH, _M_n = 2000, _M_w/_M_n = 1.15) were purchased from Polymer Source Inc.; _N_,_N_ dimethyl formamide (DMF, 99.8%) was purchased from Merck; 200 mesh

copper specimen grids with formvar/carbon support film (referred to as TEM grids in text) were purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences. Deionized water (DI water, resistance > 18.2 MΩ

per cm) was used for all experiments. TEM images were collected from a JEM-1400 (JEOL) Transmission Electron Microscopy operated at 100 kV. High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image was taken from

JEOL 2100F field-emission transmission electron microscope at 200 kV. SEM image was collected from a field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JEOL JSM-7001F). AFM (Dimension

ICON, Bruker) was employed to observe the nanorods in tapping mode in air. X-ray scattering experiments were performed at SWAXS Xenocs Nanoinxider with _λ_ = 0.154 nm. The sample-to-detector

distance for SAXS was 938 mm. Fit2D software was used to analyze the obtained SAXS data. PREPARATION OF (AUNR-LIGAND)@PSPAA (ASPECT RATIO IS ABOUT 18.0 ± 1.2) AuNRs with high aspect ratio

were prepared according to seed-mediated synthesis by Murphy and co-workers28. The AuNRs obtained from 50 mL of solution were collected and purified by centrifugation and washed by DI water

for two times to remove the excess CTAB (Supplementary Fig. 41).Then the purified AuNRs were dispersed in 2.5 mL of DI water to obtain the AuNR solution (stored at 5 °C before use). The

encapsulation method was modified from our previously published method with minor modifications. In a typical encapsulation process, 130 μL of AuNR solution and 70 μL of DI water were added

into a mixture prepared by mixing DMF (820 μL) and PSPAA (80 μL, 8 mg/mL in DMF). Then thiol ligand such as 2-naphthalenethiol (1) or biphenyl-4-thiol (2) or thiol-terminated polystyrene (3)

or 1-dodecanethiol (4), or 1-octadecanethiol (5), or 1, 2 dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphothioethanol (sodium salt) (6) was added in the above mixture. Finally, the mixture was heated at

110 °C for 2 h, and then allowed to slowly cool down till room temperature. The concentration of the ligand in the encapsulation step was shown in Supplementary Fig. 22. PREPARATION OF

(AUNR-6)@PSPAA (ASPECT RATIO IS ABOUT 2.8 ± 0.5) Au nanorods with low aspect ratio were prepared using method by Murphy and co-workers29. For encapsulation, 1 mL of obtained pristine AuNR

solution was centrifuged at 9800×_g_ for 10 min to obtain ~10 μL concentrated solution. The concentrated solution was then diluted by 1 mL of DI water, and centrifuged at 9800×_g_ for 8 min

to obtain ~10 μL concentrated solution. This process was repeated twice to remove the excess CTAB. The washed AuNR was diluted by DI water to 200 μL, and then added into a mixture that was

prepared by mixing DMF (820 μL) and PSPAA (80 μL, 8 mg/mL in DMF). Then 60 μL of ligand-6 (2 mg/mL in EtOH) was added into the above mixture. Finally, the mixture was heated at 110 °C for 2

h, and then allowed to slowly cool down till room temperature. PREPARATION OF (AUNS-1)@PSPAA Gold nanospheres (AuNS, about 40 nm in diameter) were prepared according to literature procedures

by sodium citrate reduction of HAuCl430. Citrate stabilized AuNS solution was centrifuged at 9800×_g_ for 10 min to obtain ~10 μL concentrated solution. The concentrated solution was then

diluted by DI water (200 μL), and then added into a mixture that was prepared by mixing DMF (820 μL) and PSPAA (80 μL, 8 mg/mL in DMF). Then ligand-1 (5 μL, 10 mg/mL in DMF) was added in the

above mixture. Finally, the mixture was heated at 110 °C for 2 h, and then allowed to slowly cool down till room temperature. PREPARATION OF (BIPYRAMID-1)@PSPAA Gold bipyramids were

prepared according to the literature31. One milliliter of pristine bipyramid solution was centrifuged at 5200×_g_ for 8 min to obtain ~10 μL concentrated solution. The concentrated solution

was then diluted by 1 mL of CTAB (1 mM), and centrifuged at 4000×_g_ for 6 min to obtain ~10 μL concentrated solution (this process was repeated twice to remove the HCl). The 10 μL of

concentrated solution was diluted to 0.5 mL with DI water, and was centrifuged at 2000×_g_ for 8 min to obtain ~10 μL concentrated solution to remove the excess CTAB. The washed bipyramid

was diluted by DI water to 200 μL, and then added into a mixture that was prepared by mixing DMF (820 μL) and PSPAA (80 μL, 8 mg/mL in DMF). Then 5 μL of ligand-1 (10 mg/mL in DMF) was added

into the above mixture. Finally, the mixture was heated at 110 °C for 2 h, and then allowed to slowly cool down till room temperature. PREPARATION OF (NANOPRISMS-1)@PSPAA Triangular gold

nanoprisms were prepared using method by Zhang and co-workers32. One milliliter of pristine nanoprism solution was centrifuged at 5200×_g_ for 6 min to obtain ~10 μL concentrated solution.

The concentrated solution was then diluted by 1 mL of CTAB (1 mM), and centrifuged at 5200×_g_ for 5 min to obtain ~10 μL concentrated solution (this process was repeated twice to remove the

CTAC). The 10 μL of concentrated solution was diluted to 0.8 mL with DI water, and centrifuged at 2000×_g_ for 5 min to obtain ~10 μL concentrated solution. The washed nanoprisms were

diluted by DI water to 200 μL, and then added into a mixture that was prepared by mixing DMF (820 μL) and PSPAA (80 μL, 8 mg/mL in DMF). Then 5 μL of ligand-1 (10 mg/mL in DMF) was added

into the above mixture. Finally, the mixture was heated at 110 °C for 2 h, and then allowed to slowly cool down till room temperature. TRANSFORMATION OF (AU-LIGAND)@PSPAA The obtained

(Au-ligand)@PSPAA mixture (1 mL) was centrifuged for 8 min to a volume of ~10 μL (4000×_g_ for (AuNR-ligand)@PSPAA and 9800×_g_ for (AuNS-1)@PSPAA)). The concentrated mixture was diluted by

600 μL of DI water and then centrifuged to a volume of ~10 μL (this process was repeated twice to remove the residual DMF and ligand). Finally, to induce the transformation of PSPAA, the

concentrated mixture was diluted by 0.6 mL of DI water and heated at designed temperature for different duration (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 22). The transformed

(Au-ligand)@PSPAA can be directly used for the next metal deposition. Supplementary Fig. 42 shows the experimental setup in an airing chamber for the transformation of (AuNR-ligand)@PSPAA,

and the table shows the inside/inner pressure of the bottle at different heating temperature. The cubage of the little bottle is about 4 mL, and there is a sealing pad in the bottle cap to

avoid the gas leakage. The bottle can bear the pressure even if the water was heated to 120 °C. But for security sake, the glass screen of the airing chamber should be pulled down during the

experiment. SILVER DEPOSITION ON TRANSFORMED (AUNR-LIGAND)@PSPAA In a typical synthesis, 5 μL of hydroquinone (1 mM) was added into 0.6 mL of transformed (AuNR-ligand)@PSPAA suspension.

After vortex for several seconds, 5 μL of AgNO3 (1 mM) was added into the above mixture. The mixture was left undisturbed for 12 h at room temperature. Specially, for constructing two silver

tips on the transformed (bipyramid-1)@PSPAA, the pH value of the mixture was adjusted from 7 to 11, without changing the concentration of hydroquinone and AgNO3. PREPARATION OF

(AUNR-1)@PSPAA-PD TIPS-AG RINGS In a typical synthesis, 0.6 mL of water dispersed (AuNR-1)@PSPAA was heated at 105 °C for 2 h and cooled down to room temperature. Then 5 μL of hydroquinone

(10 mM) and 5 μL of Na2PdCl4 (10 mM) were added. The mixture was undisturbed at room temperature for 12 h to prepare Pd-tipped (AuNR-1)@PSPAA. After being centrifuged to a volume of ~10 μL,

0.6 mL of water was added into the concentrated Pd-tipped AuNR@PSPAA suspension, and heated at 110 °C for 3 h to further contract. After cooled down to room temperature, 5 μL of hydroquinone

(1 mM) and 5 μL of AgNO3 (1 mM) was added, and stand for 12 h to form silver rings on the new exposed gold surface. The length of Pd tips and the position of Ag ring can be controlled by

increasing the first heating duration to 3 h. COUPLING OF (AUNR-1)@PSPAA-AG Firstly, (AuNR-1)@PSPAA-Ag was prepared based on the contracted (AuNR-1)@PSPAA (the contraction duration is about

2 h). The obtained solution containing (AuNR-1)@PSPAA-Ag was centrifuged at 2000×_g_ for 5 min to a volume of ~10 μL. Then 0.5 mL of DI water was added followed by adding 5 μL of sodium

sulfide (1 mM). The mixture was kept for 2 h at room temperature to realize the coupling of AuNRs. PREPARATION OF TEM SAMPLES TEM grids were pretreated for 30 s in a Harrick plasma

cleaner/sterilizer to improve their hydrophilicity. The hydrophilic face of the TEM grid was then placed in contact with the sample solution. Filter paper was used to wick off the excess

solution on the TEM grid, which was then left to dry in air for 10 min. For some samples, (NH4)6Mo7O24 was used as the negative stain, so that the polymer shells appear white against the

stained background. PREPARATION OF SEM SAMPLES A silicon wafer (about 0.6 cm2) was pretreated with O2 plasma for 15 min to improve its surface hydrophilicity. The wafer was then

functionalized with an amino group by reacting with APTES solution (5 mM) for 30 min. Subsequently, the wafer was washed by EtOH for several times. Water dispersed sample was dropped on the

wafer and stand for 30 min. Then the redundant solution on the wafer was drawn off, and the wafer with sample was kept at room temperature until dry. DATA AVAILABILITY All data generated or

analyzed during this study are present in the main text and the Supplementary Information. Additional data are available from the authors on reasonable request. REFERENCES * Choueiri, R. M.

et al. Surface patterning of nanoparticles with polymer patches. _Nature_ 538, 79–83 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central ADS Google Scholar * Wang, Y., Xu, J. & Chen, H.

Emerging chirality in nanoscience. _Chem. Soc. Rev._ 42, 2930–2962 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Xia, Y., Xia, X. & Peng, H. C. Shape-controlled synthesis of colloidal

metal nanocrystals: thermodynamic versus kinetic products. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 137, 7947–7966 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Tao, A. R., Habas, S. & Yang, P. Shape

control of colloidal metal nanocrystals. _Small_ 4, 310–325 (2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wang, Y., He, J., Liu, C., Chong, W. H. & Chen, H. Thermodynamics versus kinetics in

nanosynthesis. _Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl._ 54, 2022–2051 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wu, Y., Wang, D. & Li, Y. Understanding of the major reactions in solution

systhesis of functional nanomaterials. _Sci. China Mater._ 59, 938–996 (2016). Article Google Scholar * Zhang, Z. & Glotzer, S. C. Self-assembly of patchy particles. _Nano Lett._ 4,

1407–1413 (2004). Article CAS PubMed ADS Google Scholar * Nie, Z. et al. Self-assembly of metal-polymer analogues of amphiphilic triblock copolymers. _Nat. Mater._ 6, 609–614 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wang, F., Cheng, S., Bao, Z. & Wang, J. Anisotropic overgrowth of metal heterostructures induced by a site-selective silica coating. _Angew. Chem.

Int. Ed. Engl._ 52, 10344–10348 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Huang, Z. et al. Collapsed polymer-directed synthesis of multicomponent coaxial-like nanostructures. _Nat.

Commun._ 7, 12147 (2016). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central ADS Google Scholar * Schlenoff, J. B., Li, M. & Ly, H. Stability and self-exchange in alkanethiol monolayers. _J. Am.

Chem. Soc._ 117, 12528–12536 (1995). Article CAS Google Scholar * Walther, A. & Muller, A. H. Janus particles: synthesis, self-assembly, physical properties, and applications. _Chem.

Rev._ 113, 5194–5261 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, T., Yang, M., Wang, X., Tan, L. H. & Chen, H. Controlled assembly of eccentrically encapsulated gold

nanoparticles. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 130, 11858–11859 (2008). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Feng, Y., Wang, Y., Song, X., Xing, S. & Chen, H. Depletion sphere: explaining the

number of Ag islands on Au nanoparticles. _Chem. Sci._ 8, 430–436 (2017). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, T., Chen, G., Xing, S., Wu, T. & Chen, H. Scalable routes to Janus

Au−SiO2and ternary Ag−Au−SiO2 Nanoparticles. _Chem. Mater._ 22, 3826–3828 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Xing, S. et al. Reducing the symmetry of bimetallic Au@Ag nanoparticles by

exploiting eccentric polymer shells. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 132, 9537–9539 (2010). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Wang, H., Chen, L., Feng, Y. & Chen, H. Exploiting core-shell

synergy for nanosynthesis and mechanistic investigation. _Acc. Chem. Res._ 46, 1636–1646 (2013). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Chen, G. et al. High-purity separation of gold

nanoparticle dimers and trimers. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 131, 4218–4219 (2009). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mai, Y. & Eisenberg, A. Self-assembly of block copolymers. _Chem. Soc.

Rev._ 41, 5969–5985 (2012). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Zhang, L. F. & Eisenberg, A. Multiple morphologies and characteristics of “crew-cut” micelle-like aggregates of

polystyrene-b-poly(acrylic acid) diblock copolymers in aqueous solutions. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 118, 3168–3181 (1996). Article CAS Google Scholar * Rahman, M. & Brazel, C. The

plasticizer market: an assessment of traditional plasticizers and research trends to meet new challenges. _Prog. Polym. Sci._ 29, 1223–1248 (2004). Article CAS Google Scholar * Pradhan,

N., Reifsnyder, D., Xie, R. G., Aldana, J. & Peng, X. G. Surface ligand dynamics in growth of nanocrystals. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 129, 9500–9509 (2007). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Wu, Y. et al. Composite mesostructures by nano-confinement. _Nat. Mater._ 3, 816–822 (2004). Article CAS PubMed ADS Google Scholar * Zheng, Z., Tachikawa, T. & Majima, T.

Plasmon-enhanced formic acid dehydrogenation using anisotropic Pd-Au nanorods studied at the single-particle level. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 137, 948–957 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Habas, S. E., Lee, H., Radmilovic, V., Somorjai, G. A. & Yang, P. Shaping binary metal nanocrystals through epitaxial seeded growth. _Nat. Mater._ 6, 692–697 (2007). Article

CAS PubMed ADS Google Scholar * Pang, X. C., Zhao, L., Han, W., Xin, X. K. & Lin, Z. Q. A general and robust strategy for the synthesis of nearly monodisperse colloidal nanocrystals.

_Nat. Nanotechnol._ 8, 426–431 (2013). Article CAS PubMed ADS Google Scholar * Feng, Y. et al. Achieving site-specificity in multistep colloidal synthesis. _J. Am. Chem. Soc._ 137,

7624–7627 (2015). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gole, A. & Murphy, C. J. Seed-mediated synthesis of gold nanorods: role of the size and nature of the seed. _Chem. Mater._ 16,

3633–3640 (2004). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gole, A. & Murphy, C. J. Azide-derivatized gold nanorods: functional materials for “click” chemistry. _Langmuir_ 24, 266–272 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Frens, G. Controlled nucleation for the regulation of the particle size in monodisperse gold suspensions. _Nat. Phys. Sci._ 241, 20–22 (1973). Article

CAS ADS Google Scholar * Lee, J. H., Gibson, K. J., Chen, G. & Weizmann, Y. Bipyramid-templated synthesis of monodisperse anisotropic gold nanocrystals. _Nat. Commun._ 6, 7571

(2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Chen, L. et al. High-yield seedless synthesis of triangular gold nanoplates through oxidative etching. _Nano Lett._ 14,

7201–7206 (2014). Article CAS PubMed ADS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank the MOE (RG 14/13) of Singapore, the National Natural Science Foundation of China

(nos. 21673117, 21676063, and U1462103), Jiangsu Provincial Foundation for specially-appointed professor, start-up fund at Nanjing Tech University, and HIT Environment and Ecology Innovation

Special Funds for financial supports. Z.W. thanks the support from China Scholarship Council (CSC) program. G.W. acknowledges the Tsinghua Scholarship for Overseas Graduate Studies. B.H.

acknowledges the Jiangsu National Synergetic Innovation Center for Advanced Materials (SICAM) Scholarship for Overseas Graduate Students. AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * Zhenxing Wang and

Bowen He contributed equally to this work. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Institute of Advanced Synthesis, School of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering, Jiangsu National Synergetic Innovation

Center for Advanced Materials, Nanjing Tech University, Nanjing, 211816, China Zhenxing Wang, Bowen He & Hongyu Chen * MIIT Key Laboratory of Critical Materials Technology for New Energy

Conversion and Storage, State Key Laboratory of Urban Water Resource and Environment, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, 150001, China

Zhenxing Wang & Lu Shao * Division of Chemistry and Biological Chemistry, School of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, 21 Nanyang Link, Singapore,

637371, Singapore Zhenxing Wang, Gefei Xu, Guojing Wang, Yuhua Feng, Dongmeng Su & Hongyu Chen * College of Chemistry, Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330031, China Zhenxing Wang *

Institute of High Energy Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100049, China Jiayi Wang & Zhonghua Wu * Center for Programmable

Materials, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 639798, Singapore Bo Chen & Hua Zhang * Key Laboratory of Flexible Electronics and

Institute of Advanced Materials, Jiangsu National Synergetic Innovation Center for Advanced Materials, Nanjing Tech University, Nanjing, 211816, China Hai Li Authors * Zhenxing Wang View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Bowen He View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Gefei Xu

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Guojing Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Jiayi Wang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yuhua Feng View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Dongmeng Su View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Bo Chen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Hai Li View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Zhonghua Wu View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Hua Zhang View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Lu Shao View author publications You can also search for this

author inPubMed Google Scholar * Hongyu Chen View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS H.C., L.S. and Z.W. designed and planned this

project, and proposed the mechanisms. Z.W. was responsible for the preparation of contraction and winding modes. G.X. was responsible for the dissociation mode. B.H. purified the AuNRs to

high purity, and helped in the syntheses and characterization of (AuNR-1)@PSPAA and (AuNR-6)@PSPAA. G.W. and Y.F. helped in the syntheses of metal tipped colloidal nanocomposites. D.S.

helped in the SEM characterization. H.L. helped in the AFM characterization. J.W. and Z.W. helped in the SAXS characterization. B.C. and H.Z. helped in the HRTEM characterization. All

authors participated in the writing of the manuscript. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Lu Shao or Hongyu Chen. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no

competing financial interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER'S NOTE: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional

affiliations. ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION PEER REVIEW FILE RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution

4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and

the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s

Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not

permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Wang, Z., He, B., Xu, G. _et al._ Transformable masks for colloidal nanosynthesis.

_Nat Commun_ 9, 563 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-02958-x Download citation * Received: 19 December 2016 * Accepted: 10 January 2018 * Published: 08 February 2018 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-02958-x SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative