- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND Temporal artery biopsy (TAB) is often performed by ophthalmology trainees without direct supervision. The traditional model of ‘see one, do one, teach one’ still prevails

in most units. Whilst it is generally a safe procedure, damage to the temporal branch of the facial nerve has been reported when harvesting the frontal branch of the superficial temporal

artery. METHODS A survey of trainees from Wessex, Wales, London and Severn deaneries was performed to look at current training techniques, anatomical knowledge and practice. RESULTS 38

trainees responded to the survey, with complete responses from 28 participants. Formal teaching of the anatomical considerations in TAB was not reported by any trainee, with informal

teaching being standard practice. Whilst 61% of respondents reported having learnt about the anatomical ‘danger zone’ for facial nerve damage, 97% of trainees chose an incision that fell

within this zone when given a choice between potential incision sites. CONCLUSION TAB remains a largely trainee-taught, trainee-performed procedure. Most trainees are not aware of how to

avoid the risk of damage to the temporal branch of the facial nerve. We suggest harvesting the parietal branch of the temporal artery via an incision outside the anatomical ‘danger zone’. In

our experience, this is an easily taught technique that minimises the potential risk of damage to the frontal branch of the facial nerve. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS

DISTRIBUTION, SCALING, AND DEPICTION OF THE TEMPORAL BRANCHES OF THE FACIAL NERVE Article Open access 02 April 2025 HARMONIZING OPHTHALMIC RESIDENCY SURGICAL TRAINING ACROSS EUROPE: A

PROPOSED SURGICAL CURRICULUM Article 17 March 2023 SUB-TENON’S ANAESTHESIA FOR MODERN EYE SURGERY—CLINICIANS’ PERSPECTIVE, 30 YEARS AFTER RE-INTRODUCTION Article 03 February 2021

INTRODUCTION Despite recent advances in investigative options for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis (GCA), temporal artery biopsy (TAB) remains a vital diagnostic tool [1]. Efforts to

reduce the ophthalmic complications of GCA, particularly blindness, have been addressed with guidelines that recommend urgent referral for TAB and prompt initiation of high dose steroids

[2]. One study reported vision loss in 1 in 12 patients 6 months after diagnosis [3], highlighting the need for immediate diagnosis and the initiation of treatment. However, despite clear

guidance on the requirement for TAB, most ophthalmology trainees rely on informal, often peer led, surgical training on the technique and lack formal teaching. Even then, a trainee may not

attempt their first TAB until later in their training depending on the frequency of cases. Furthermore, there is often variation in who performs TAB in different units as vascular, general

and ophthalmic surgeons frequently do so [4], thus diluting the case load for some trainees. Very few complications have been reported following temporal artery biopsy. However, the

procedure is not without risk as damage to the temporal branch of the facial nerve has been reported in the literature [5,6,7,8]. One study of 75 TABs found ongoing frontalis weakness in 10%

of patients at 6 months, reducing to 3% at a year [9]. This may result in brow droop, as a result of impaired function of the frontalis muscle, causing permanent disfigurement [9]. The

superficial temporal artery (STA) lies within the superficial temporal fascia (STF) and the temporal branch of the facial nerve (TFN) courses deeper within the fascia’s fibrofatty layer

[10]. The TFN is responsible for innervating the orbicularis oculi and frontalis muscle which are responsible for closing the eye and raising the eyebrow, respectively [4]. In some cases,

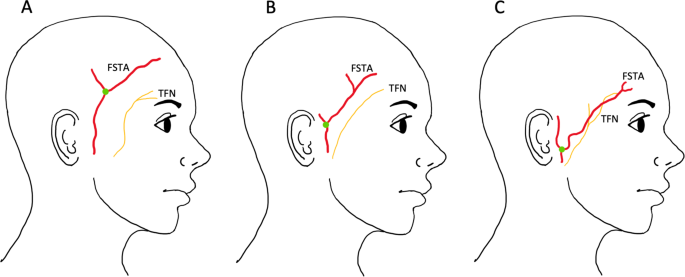

the TFN can lie directly underneath the frontal branch of the superficial temporal artery (FSTA), putting it at increased risk of damage (Fig. 1) [7, 10]. Therefore, it is essential that an

approach that avoids iatrogenic damage to the TFN is utilised. The anatomical ‘danger zone’ has been described as an area where the TFN and the FSTA are separated solely by the superficial

temporal fascia [5]. Yoon et al. defined this area as (A) the tragus of the ear, (B) the junction between the zygomatic arch and lateral orbital rim, (C) a point 2 cm above the superior

orbital rim and (D) an area superior to the tragus that is in horizontal alignment with C (Fig. 2A) [5]. Pitanguy’s line (Fig. 2B) is also a useful landmark and describes the superficial

course of the TFN from 0.5 cm below the tragus to 1.5 cm above the lateral extremity of the eyebrow [11], however anatomical variants do exist. Avoidance of these areas is necessary to

minimise the risk of damage to the TFN. Other authors have previously described a technique for harvesting the parietal branch, rather than the frontal branch, of the temporal artery [5].

This can successfully be achieved by adapting the Gilles technique [12] and making a temporal incision 2.5 cm superior and anterior to the helix of the ear (Fig. 2C incision B) [13]. The

sensitivity of harvesting the parietal branch of the temporal artery rather than the frontal branch has not been fully validated. However, recent interest in using ultrasound to diagnose GCA

has demonstrated involvement of the parietal branch and it is now routinely included when scanning patients for suspected GCA suggesting that it is reasonable to use this branch [14]. In

this study we investigated current training techniques, anatomical knowledge and practice in TAB to establish current practice. METHODS A survey was electronically distributed, using the

Survey Monkey platform, to ~100 trainees from the Wessex, Wales, London and Severn deaneries during 2019. Questions asked included year of training, number of TABs performed, and the method

of training received. Trainees were also required to select where they would make their initial incision based on a series of diagrams and were asked about their awareness of the anatomical

‘danger zone’. All questions were designed to allow the respondents to select from options. Our study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Consent was obtained from all

individual participants included in the study. RESULTS 38 responses were received out of approximately 100 distributed surveys. Ten respondents started the survey but only completed the

first few questions and were therefore excluded from the analysis, leaving 28 complete responses. Responses were received from trainees from ST2 to ST7 level with most being from ST7

trainees. The question concerning the type of training received revealed that 28 (100%) respondents received informal training from their colleagues in the format of ‘See one, do one, teach

one’. 8/28 trainees (28.6%) had performed between 1 and 5 temporal artery biopsies; 8/28 (28.6%) had performed between 5 and 10 temporal artery biopsies; 5/28 (17.9%) had performed between

10 and 20 temporal artery biopsies; 6/28 (21.4%) had performed greater than 20 temporal artery biopsies, whilst 1/28 (3.6%) trainee had not yet performed a temporal artery biopsy as part of

their training (Fig. 3). Questions concerning key anatomical landmarks revealed that 17/28 (61%) reported having been taught about the concept of a ‘danger zone’ for injury to the temporal

branch of the facial nerve (TFN) (Fig. 2A). 5/28 (17.9%) respondents were aware of Pitanguy’s line (Fig. 2B) whereas 27/28 (96.4%) respondents were able to correctly identify the ‘danger

zone’ from the images provided. Interestingly however, when asked where they would make their initial incision, 27/28 (96.4%) respondents would choose to make their incision within the

‘danger zone’. (Table 1) shows possible incision points and the number of respondents that would select each incision (Fig. 2C). DISCUSSION This is the first multi-deanery study to

investigate temporal artery biopsy training for ophthalmology trainees in the UK. Ophthalmologists in the UK are required to undertake a 7-year Ophthalmic specialist training programme which

has an extensive curriculum comprising of a number of core learning outcomes that must be achieved by the end of the final year [15]. A key domain in this curriculum is surgical skills, and

competency in temporal artery biopsy is a necessary requirement with the target year of achievement being year 7 [16]. Key outcomes of the skill include the consideration of risks and

benefits of the procedure as well as a good understanding of landmarks and branches of the facial nerve [16]. At present, our results confirm that the most common approach to TAB training is

in the format of ‘See one, do one, teach one’. This means that trainees are not receiving formal teaching. In other areas of ophthalmic surgical training such as cataract surgery,

implementation of a structured surgical curriculum involving the use of wet labs and simulator training, has been demonstrated to reduce surgical complications [17]. Trainees might benefit

from a structured course involving an e-learning tutorial with modules covering the contents and anatomical landmarks of the temporal region, the risk and benefits of the procedure and a

step-by-step guide to the procedure. This may be followed by a video of the procedure and a supervised wet-lab experience before finally entering theatre. There are many online videos

demonstrating different approaches to TAB [18, 19]. UK trainees may benefit from a teaching video approved by The Royal College of Ophthalmologists, and available on their website. The use

of informal teaching is likely multifactorial and may result from the shared performance of the procedure across multiple specialities. A recent retrospective cohort study reviewing the

specialities performing TAB over a 10-year period in Canada found that general surgeons performed the most temporal artery biopsies which was closely followed by ophthalmologists and plastic

surgeons [20]. It is not clear whether the UK experience follows this, but it is certainly the authors’ experience that in some units, ophthalmologists perform very few TABs. Lotfipour et

al. evaluated trends in cataract surgery training curriculum and proposed that the choice of informal teaching may be a result of lack of faculty time and the perception that an

apprentice-type approach to teaching negates the need for formal teaching [21]. However, in recent years there has been a shift away from an informal surgical apprenticeship model, largely

as a result of restricted training hours and limitations in unsupervised experiential learning [22]. From the perspective of future practice, the use of informal teaching can lead to

surgical procedures being influenced by the teaching surgeons’ personal preferences. This can result in less room to propose safer alternatives to a surgical technique. A safer approach to

TAB would be to harvest the parietal branch of the superficial temporal artery, effectively eliminating the risk of damage to the facial nerve. This has previously been discussed by other

authors [4], yet this technique is seldom used by ophthalmologists. The artery can be located and marked by following pulsations from the tragus, after removing a small amount of hair. A

handheld doppler can also be used to confirm the course of the artery if required. Subsequently, TAB can be performed as normal. While many trainees are performing temporal artery biopsies

before their final year, with some performing greater than twenty biopsies, the majority of respondents indicated that they would make their initial incision within the ‘danger zone’. This

would suggest that the teaching received by trainees lacks emphasis on the ‘danger zone’ as an anatomical region that should be avoided where possible. Therefore, we propose mapping the

‘danger zone’ during preoperative planning of TAB and avoiding the ‘danger zone’ when performing temporal artery biopsy. Our survey reveals that the majority of trainees are aware of the

anatomical ‘danger zone’, however less than one-fifth of respondents are aware of Pitanguy’s line. The concept of Pitanguy’s line does have its limitations, as the most at-risk temporal

branch of the facial nerve typically has multiple rami crossing the zygomatic arch [23, 24]. However, marking it out preoperatively can help the surgeon to delineate a definite ‘no go’ zone

(Fig. 2D) within the danger area that should be avoided, with increasing safety the more superior and lateral the incision point. There are some limitations to this study. A primary

limitation is the generalisation of these results. This is because the survey was distributed to a limited number of deaneries and in addition not all trainees responded. Furthermore, we

received a number of incomplete surveys which were excluded from the analysis. Nonetheless, our study provides an insight into how trainees are being taught to perform a TAB and assists in

evoking discussion regarding how training can be made safer. CONCLUSION Despite the development of formal surgical teaching and simulation in other branches of ophthalmic surgery, the

teaching of TAB continues to be taught to trainees, by trainees via the traditional apprenticeship method. Harm to patients may be avoided by raising awareness of the ‘danger zone’ and

harvesting the parietal branch of the superficial temporal artery. Formal teaching on how to map the ‘danger zone’ and Pitanguy’s line and a demonstration of the above technique would be a

beneficial addition to teaching trainees how to perform a TAB. This is particularly relevant as we are currently seeing an expansion in different methods of training, including the use of

online resources, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This has allowed us to be more creative and resourceful in the way we approach teaching which is proving to be beneficial in many

sectors. TAB is a suitable technique that can be optimised with the addition of virtual training, and this will hopefully make the procedure safer for patients as well as instil confidence

in our trainees. SUMMARY WHAT WAS KNOWN BEFORE * Temporal artery biopsy (TAB) is generally a safe procedure to perform however, there is a risk of damaging the temporal branch of the facial

nerve. There is currently no formal teaching of the procedure to ophthalmology trainees. The traditional model of ‘see one, do one, teach one’ still prevails in most units. WHAT THIS STUDY

ADDS * This study highlights that TAB still remains a primarily trainee-taught, trainee-performed procedure. Ophthalmology trainees will benefit from formal teaching on the anatomical danger

zone and how best to avoid it. REFERENCES * Mackie SL, Dejaco C, Appenzeller S, Camellino D, Duftner C, Gonzalez-Chiappe S, et al. British Society for Rheumatology guideline on diagnosis

and treatment of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology. 2020;59:e1–e23. Article Google Scholar * Dasgupta B. Concise guidance: diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis. Clin Med.

2010;10:381. Article Google Scholar * Yates M, MacGregor AJ, Robson J, Craven A, Merkel PA, Luqmani RA, et al. The association of vascular risk factors with visual loss in giant cell

arteritis. Rheumatology. 2017;56:524–8. Google Scholar * Gunawardene AR, Chant H. Facial nerve injury during temporal artery biopsy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:257–60. Article CAS

Google Scholar * Yoon MK, Horton JC, McCulley TJ. Facial nerve injury: a complication of superficial temporal artery biopsy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152:251–5. e1 Article Google Scholar *

Bhatti MT, Goldstein MH. Facial nerve injury following superficial temporal artery biopsy. Dermatologic Surg. 2001;27:15–7. CAS Google Scholar * Murchison AP, Bilyk JR. Brow ptosis after

temporal artery biopsy: incidence and associations. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2637–42. Article Google Scholar * Slavin ML. Brow droop after superficial temporal artery biopsy. Arch

Ophthalmol. 1986;104:1127. Article CAS Google Scholar * Rison RA. Branch facial nerve trauma after superficial temporal artery biopsy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:34. Article

Google Scholar * Shin K-J, Shin HJ, Lee S-H, Koh K-S, Song W-C. Surgical anatomy of the superficial temporal artery to prevent facial nerve injury during arterial biopsy. Clin Anat.

2018;31:608–13. Article Google Scholar * Pitanguy IVO, Ramos AS. The frontal branch of the facial nerve: the importance of its variations in face lifting. Plast Reconstr Surg.

1966;38:352–6. * Gillies HD, Kilner TP, Stone D. Fractures of the Malar-zygomatic compound: with a description of a new X-ray position. Br J Surg. 1927;14:651–6. Article Google Scholar *

Markose G, Graham RM. Gillies temporal incision: an alternate approach to superficial temporal artery biopsy. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;55:719–21. Article CAS Google Scholar *

Schäfer VS, Jin L, Schmidt WA. Imaging for diagnosis, monitoring, and outcome prediction of large vessel vasculitides. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020;22:76. Article Google Scholar * The Royal

College of Ophthalmologists. Curriculum for ophthalmic specialist training. https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/curriculum/ost/. * The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Surgical skills SS11 London.

https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/learningoutcomes/ss11/. * Rogers GM, Oetting TA, Lee AG, Grignon C, Greenlee E, Johnson AT, et al. Impact of a structured surgical curriculum on ophthalmic resident

cataract surgery complication rates. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:1956–60. Article Google Scholar * Perry JD. Temporal artery biopsy. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2018.

https://www.aao.org/clinical-video/temporal-artery-biopsy-22. * Patel BCK, Joos ZP. Temporal artery biopsy: moran core: clinical ophthalmology resource for education; 2016.

http://morancore.utah.edu/section-13-refractive-surgery/temporal-artery-biopsy/. * Micieli JA, Micieli R, Margolin EA. A review of specialties performing temporal artery biopsies in Ontario:

a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3:E281–E5. Article Google Scholar * Lotfipour M, Rolius R, Lehman EB, Pantanelli SM, Scott IU. Trends in cataract surgery training curricula.

J Cataract Refract Surg. 2017;43:49–53. Article Google Scholar * Saleh GM, Athanasiadis I, Collin JRO. Training and oculoplastics: past, present and future. Orbit. 2013;32:111–6. Article

Google Scholar * Agarwal CA, Mendenhall SD, Foreman KB, Owsley JQ. The course of the frontal branch of the facial nerve in relation to fascial planes: an anatomic study. Plast Reconstr

Surg. 2010;125:532–7. Article CAS Google Scholar * de Bonnecaze G, Chaput B, Filleron T, Al Hawat A, Vergez S, Chaynes P. The frontal branch of the facial nerve: can we define a safety

zone? Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37:499–506. Article Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank Kang-Jae Shin et al for their figure which has been

redrawn for Fig. 1. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Heath Park, Cardiff, CF14 4XN, UK Georgia Osei * Department of Ophthalmology,

University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust, Plymouth, PL6 8DH, UK Paul Rainsbury * Department of Ophthalmology, Cardiff and Vale University Health Board, Cardiff, CF14 4XW, UK Daniel Morris

& Anjana Haridas Authors * Georgia Osei View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Paul Rainsbury View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Daniel Morris View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Anjana Haridas View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS GO was responsible for analysing and interpreting results, writing the report, creating the figures, and updating

reference lists. She provided an image of herself for “Fig. 2”. PR was responsible for designing the study protocol, writing the study protocol, and distributing the surveys. He contributed

to writing the report and provided an image of himself for “Fig. 2”. AH and DM contributed to writing the report, revised the report critically, provided feedback on the report and gave

final approval of the version to be published. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Georgia Osei. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION The individuals in Fig. 2 are not actual patients, but the co-authors of this study ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with

regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the

source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative

Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by

statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Osei, G., Rainsbury, P., Morris, D. _et al._ Temporal artery biopsy: time for a

rethink on training?. _Eye_ 37, 506–510 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-01963-1 Download citation * Received: 08 October 2021 * Revised: 19 January 2022 * Accepted: 02 February

2022 * Published: 21 February 2022 * Issue Date: February 2023 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-01963-1 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to

read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing

initiative