- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND Consumption of very-hot beverages/food is a probable carcinogen. In East Africa, we investigated esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) risk in relation to four

thermal exposure metrics separately and in a combined score. METHODS From the ESCCAPE case–control studies in Blantyre, Malawi (2017-20) and Kilimanjaro, Tanzania (2015-19), we used logistic

regression models adjusted for country, age, sex, alcohol and tobacco, to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for self-reported thermal exposures whilst consuming

tea, coffee and/or porridge. RESULTS The study included 849 cases and 906 controls. All metrics were positively associated with ESCC: temperature of drink/food (OR 1.92 (95% CI: 1.50, 2.46)

for ‘very hot’ vs ‘hot’), waiting time before drinking/eating (1.76 (1.37, 2.26) for <2 vs 2–5 minutes), consumption speed (2.23 (1.78, 2.79) for ‘normal’ vs ‘slow’) and mouth burning

(1.90 (1.19, 3.01) for ≥6 burns per month vs none). Amongst consumers, the composite score ranged from 1 to 12, and ESCC risk increased with higher scores, reaching an OR of 4.6 (2.1, 10.0)

for scores of ≥9 vs 3. CONCLUSIONS Thermal exposure metrics were strongly associated with ESCC risk. Avoidance of very-hot food/beverage consumption may contribute to the prevention of ESCC

in East Africa. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS HOT BEVERAGE INTAKE AND OESOPHAGEAL CANCER IN THE UK BIOBANK: PROSPECTIVE COHORT STUDY Article Open access 19 February 2025 EXCLUSIVE

WATERPIPE SMOKING AND THE RISK OF NASOPHARYNX CANCER IN VIETNAMESE MEN, A PROSPECTIVE COHORT STUDY Article Open access 14 August 2023 THE FUTURE BURDEN OF OESOPHAGEAL AND STOMACH CANCERS

ATTRIBUTABLE TO MODIFIABLE BEHAVIOURS IN AUSTRALIA: A POOLED COHORT STUDY Article 23 December 2022 INTRODUCTION According to global cancer burden 2020 estimates, esophageal cancer (EC) is

the sixth most common cause of death (544,076 deaths) from cancer and the eighth-most common cancer (604,100 new cases) [1]. Those diagnosed with EC have an unfavourable prognosis, for

instance a 20% 5-year survival in the United States of America [2]. There are two major histological subtypes of EC, these are esophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC)

[3]. The predominant type globally is ESCC (~88%), which is also the dominant type in geographical hotspots such as parts of China, Iran and the eastern African corridor. This corridor

stretches from Ethiopia [4] to South Africa [5] and includes several countries, for example, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. In 2020 estimates, the age standardised incidence

rates for EC were 20.3 and 15.2 per 100,000 person-years for males and females respectively in Malawi. The corresponding figures for Tanzania were 12.8 and 6.6. An extensive review of

putative aetiologic risk factors for ESCC in Africa suggests that many carcinogens and susceptibility factors that contribute to the Chinese and Iranian hotspots may also be present in

Africa, with setting-specific exposure habits or sources [6]. Studies addressing these factors have been undertaken in the past decade, now forming a strong element of the African Esophageal

Cancer Consortium [7]. To date, results point to the increased risks associated with tobacco, alcohol, poor oral health, household air pollution and the reduced intake of fruit and

vegetables [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Another putative determinant for ESCC is thermal injury from the consumption of very-hot food and beverages [3]. In 2016, the consumption of very-hot

beverages (>65 °C) was evaluated as Group 2A “probably carcinogenic to humans” by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) monographs working group [15]. Since this IARC

monograph, two prospective cohort studies in Iran and China have also reported positive associations [16, 17]. In Iran, ESCC incidence rates were raised with a higher measured first sip

temperature (relative risk (RR) 1.41 for >60 °C vs <60 °C) and were even stronger for self-reported temperature (RR 2.4 for ‘very hot’ vs ‘cold/lukewarm’) [16]. Evidence of positive

links between thermal injury and ESCC have also been reported in Africa, in 2019 in a case–control study from Kenya [18]. In contrast in a Tanzanian case–control study [10] no association

was found for either preferred beverage temperature or for burning the mouth in the past year (odds ratios ~1.1 for both). There are, however, two cross-sectional studies in Eastern Africa

suggesting that hot beverage consumption temperatures are extremely high, with mean first sip tea temperatures of 70.6 °C in Tanzania [19] and 72.6 °C in neighbouring Kenya [20]. In the

Tanzanian study, milky tea (50% high-fat milk and 50% water) was consumed 1.9 °C hotter than those who drank black tea because it had cooled at a slower rate [19]. Two further aspects of

thermal injury are important to highlight. First, effect modification was found in the aforementioned Chinese prospective cohort, with a stronger thermal injury effect among those who also

smoked tobacco or drank alcohol [17]. Second, thermal exposure metrics need to extend beyond the temperature of the first sip, to include sip volume and temperature throughout the drinking

episode, as shown in early studies of their influences on the intra-esophageal temperature [21]. Notably, a larger sip at a lower temperature can lead to the same intra-esophageal liquid

temperature as a smaller sip at a higher temperature. In the current case–control study, which was conducted in Malawi and Tanzania, we investigated self-reported markers of thermal

exposures during the ingestion of food/drink and its association with the risk of ESCC. The study benefitted from a more detailed exposure assessment than in previous studies, which we used

to generate a thermal exposure index. Explicitly, we collected the data on a range of hot beverages/foods, i.e., porridge, tea, and coffee and whether and what type of milk was added, and

several exposure correlates beyond self-perceived drinking temperature, including drinking frequency, speed and volume, waiting time prior to consumption and mouth/tongue burning frequency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS STUDY SETTING As part of the Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma African Prevention Research (ESCCAPE) programme, hospital-based case–control studies of ESCC were

conducted in Kenya, Malawi and Tanzania. The Kenya findings on ESCC and hot beverages were previously published, as already mentioned [18], and herein we analysed the data from Malawi and

Tanzania. The Malawian study took place at the tertiary Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, which has endoscopy services, in Blantyre the capital city of Malawi’s Southern Region. The

Tanzanian study was conducted in northern Tanzania in the Kilimanjaro Region. The tertiary hospital, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC) is in the Moshi municipality which is the

regional capital. It has endoscopy facilities. For the purpose of the study, other Kilimanjaro hospitals referred patients to KCMC. They were all within 70 km of KCMC: Hai and Siha District

Hospitals, Huruma Hospital, Kibosho Hospital and Machame Lutheran Hospital. However, none of these other hospitals has endoscopy services, but Huruma has barium swallow capability. As some

EC patients were too ill to travel to KCMC, interviewers travelled, at least monthly, to these outlying hospitals to conduct interviews. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA For both countries, cases were

those ≥18 years of age with a new ESCC diagnosis. In Malawi, all cases had an endoscopy pinch biopsy for histological examination and results that ruled out ESCC were excluded (e.g.,

adenocarcinoma). In Tanzania, histological confirmation was obtained for the majority of cases, but additional cases were included on the basis of imaging (barium swallow) or clinical

criteria (difficulty swallowing solids/liquids and substantial weight loss). The inclusion of non-histologically confirmed cases can be justified because previous studies found that 86% of

endoscopically diagnosed EC patients had obstruction, i.e., solid/liquid dysphagia symptoms are very specific [22]. Furthermore, studies from the Eastern African EC corridor indicate that

the ESCC subtype comprised 90% or greater of EC [23, 24]. Recruitment of controls was carried out so as to ensure age and sex frequency matching with at least one control for every case. In

both countries, adults aged 18 years of age or older who were inpatients, out-patients or visitors at the same hospitals as for case recruitment were approached and were invited to

participate. Controls did not have cancer or digestive disease diagnosis. QUESTIONNAIRE AND EXPOSURE ASSESSMENT In both countries, a face-to-face questionnaire was administered by trained

research assistants. Data regarding sociodemographic details, lifestyle and hot beverage/food consumption were collected in real time using a bespoke ESCCAPE study mobile phone application

programmed by Mobenzi. Concerning hot beverage/food thermal exposure metrics, participants from both countries were asked whether they ever consumed (in cases, before they were ill) each of

the following hot beverages/food: tea, coffee and porridge (separately). If they answered yes to the question, they were then also asked a series of questions about their habits for that

particular drink/food: the frequency of consumption, the perceived consumption temperature (‘warm’, ‘hot’, ‘very hot’ or ‘extremely hot’), how long they waited before drinking/consuming

(>5, 2 to 5 and <2 minutes), the consumption speed (‘slow’, ‘normal’, ‘fast’ and ‘extremely fast’) and the average number of times their mouth/tongue was burnt per month. For tea and

coffee, whether and when milk was added was also collected. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS Hot beverage drinking habits in controls were first examined, i.e., the closest available representation of

the study’s source population. Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests were used, where appropriate, to determine if the beverage/food consumption temperature, dichotomised into very/extremely

hot vs warm/hot, varied by known ESCC risk factors which could confound the association between thermal injury and ESCC. We then used logistic regression models to estimate the odds ratios

(ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the association between thermal injury markers and risk of ESCC. All models were minimally adjusted for the design factors sex using a binary

indicator and indicators for 5-year age categories as is advised by Breslow and Day [25]. Thereafter models were further adjusted for known risk factors for ESCC, including binary

indicators for ever alcohol consumption and ever tobacco use. Finer adjustment for the intensity of alcohol or tobacco consumption was not deemed necessary as thermal exposures were not

strongly correlated with any ESCC risk factors. Country-specific results were first examined and because they did not differ substantially, a combined model further adjusted for the country

was also fitted. Thermal injury metrics were fitted first as categorical variables, with the category corresponding to the lowest expected thermal injury as the reference, unless the number

of subjects in this group was very low (<10 cases or controls in either country). These metrics were also fitted as a linear term, assigning scores as follows. For temperature: warm = 0,

hot = 1, very hot = 2, extremely hot = 3; speed: slow = 0, normal = 1, fast = 2, extremely fast = 3; and waiting time in minutes (min): >5 min=1, 2 to 5 min = 2, <2 min = 3. We first

analysed the above metrics separately for tea, coffee and porridge consumption. Thereafter, a participant was categorised under the highest temperature at which they consumed tea, coffee or

porridge. A similar approach was applied for waiting time and speed, i.e., using the highest thermal exposure category across tea, coffee and porridge. For the number of mouth/tongue burns

per month, the total burns across the three food items was calculated and then categories were assigned the following scores: less than two burns = 0, two burns = 1, three to five burns = 2

and six or more burns = 3. Finally, we generated a thermal exposure composite index, which was the sum of the temperature + speed + waiting time + mouth burning frequency scores for the

three food items just specified. Individuals’ thermal exposure composite scores ranged from 1 to 12. We also investigated the possible interaction of hot beverage/food consumption with sex,

age, alcohol and tobacco use using likelihood ratio tests for an interaction term between a unit increase in the thermal exposure index and each potential effect modifier. Finally, we

conducted sensitivity analyses of the modelling approach, by comparing the OR obtained from a pooled analysis of data from the two countries (as described above) to that from a

random-effects meta-analytic approach of the country-specific ORs. For statistical analysis, Stata version 17BE (StataCorp LP College Station, TX) was used. RESULTS PARTICIPANT AND EXPOSURE

CHARACTERISTICS Recruitment occurred between November 2015 and December 2019 in Tanzania and between June 2017 and May 2020 in Malawi. During this time, in Tanzania 345 cases were approached

of whom 322 (93%) agreed to participate. Due to a having non-ESCC histology, twelve consented cases were excluded, leaving 310 cases. The majority of these cases 244 (79%) were recruited at

KCMC. In Malawi, 569 cases were approached and 553 (97%) agreed, of which 539 (97%) had histology which did not rule out ESCC. Control participation percentages were over 99% in Tanzania

(313/314) and 94% (593/629) in Malawi. Among participating controls, in Tanzania most (76%) controls were hospital visitors, whilst 17% were hospital out-patients and 7% inpatients, whereas

in Malawi, the corresponding percentages were 52, 12 and 36% respectively. Thus in total, the present analyses are based on 849 cases and 906 controls (Table 1). The mean age at diagnosis in

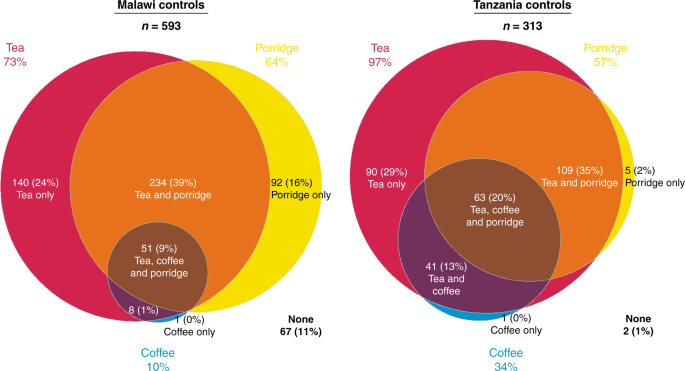

Malawi was 57 years and 64 years in Tanzania. The male:female case ratio in Malawi was 1.4, and in Tanzania 3.2. HOT BEVERAGE AND PORRIDGE CONSUMPTION HABITS IN CONTROLS Everyone except two

controls (1%) consumed hot tea, coffee and/or porridge in Tanzania, whereas in Malawi, 67 (11%) controls did not consume any of these hot foods (Fig. 1)—proportionally, this Malawian group

who did not consume any hot foods tended to be male (42/67 = 63%) compared to 56% (293/526) of hot food consumers who were men. Among controls, in both countries tea was the most commonly

consumed hot beverage: 73% (433/593) of controls consumed tea in Malawi and 97% (303/313) in Tanzania. In Malawi, 10% of controls drank hot coffee, whilst this percentage was 34% in

Tanzania. Consumption of hot porridge among controls was more similar across countries: Malawi (64%) and Tanzania (57%). In Malawi, the median age at which porridge consumption started was 5

years, tea at 10 years and coffee at 23 years, whilst in Tanzania consumers commenced at younger ages: 1, 5 and 15 years, respectively. Median daily tea drinking volumes were high in

Tanzania for both coffee and tea (500 mL), with limited seasonal variation, whereas in Malawi, these were lower at 250 mL in warm and 300 mL in cooler months. The median number of porridge

servings per week was three and two for Malawi and Tanzania respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). Of the participants (cases and controls) who drank both tea and coffee, 91% (314/345)

consumed both beverages at the same temperature, thus combining the hottest of tea or coffee temperature in later analyses typically reflects the same temperature. In Malawi among controls

who drank milk (in tea or otherwise), several types of milk were used: 38% (140/377) used fresh cow’s milk, 36% (137/377) used processed in cartons or plastic sachets, 26% used powdered milk

(99/377) and <1% fresh goat’s milk. In Tanzania among the 277 controls who drank milk, fresh cow’s milk was always used. Of the controls in Malawi who drank milky tea, 52% (45/86)

prepared it by boiling the milk together with water, whereas this was always the habit in Tanzania. Almost all Tanzanians consumed tea from a thermal flask, whereas Malawians used flasks and

teapots on the fire or table. Among tea drinkers, correlates of drinking extremely/very-hot tea (vs warm/hot) are shown in Supplementary Table S1. A higher prevalence of extremely/very-hot

drinkers was found in Tanzania men who drank alcohol regularly, but not in Tanzanian women or in Malawian participants. In Tanzanian men, extremely hot/very-hot drinking was also more common

among those who ever smoked tobacco (_P_ < 0.001), but not in other groups. ASSOCIATIONS WITH ESCC RISK In the models adjusted for tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption, all four

thermal exposure measures were positively associated with ESCC risk. Consistent across countries, ‘very hot’ compared to ‘hot’ tea or coffee drinkers had almost a two-fold increase in ESCC

risk: ORs were 1.89 (95% CI: 1.34, 2.67) and 1.93 (95% CI: 1.26, 2.96) in Malawi and Tanzania, respectively. These exposure groups were not rare: 24% of controls in both countries

characterised themselves as ‘extremely/very hot’ drinkers of tea/coffee. Furthermore, those who consumed their tea or coffee within 2 min of pouring it into their cup/mug, compared to those

who waited over 5 min, had an increased risk of ESCC: ORs were 1.56 (95% CI: 1.07, 2.27) and 1.26 (95% CI: 0.82, 1.93) in Malawi and Tanzania respectively (Table 2). Those who drank these

beverages at a “normal” compared to a “slow” speed also had a raised ESCC risk with ORs of 1.97 (95% CI: 1.47, 2.64) and 2.24 (95% CI: 1.48, 3.39) in Malawi and Tanzania, respectively. Most

participants in Tanzania (86%) reported no mouth/tongue burns in an average month, whereas in Malawi more than half of cases and controls reported at least one burn per month and in this

country, an increasing number of burns was associated with raised ESCC risk: the OR for ≥6 burns per month vs. zero was 2.07 (95% CI: 1.27, 3.35), _P_-trend <0.01, Fig. 2). The positive

associations with ESCC were generally similar in unadjusted and adjusted analyses, except in Tanzania where the unadjusted effects tended to be larger due to the aforementioned confounding.

The associations with these metrics separately for tea (Supplementary Table S2) were similar to those of tea + coffee combined results. For porridge, in general, associations with each

thermal injury metric were consistent with those for hot drinks where exposure contrasts were present. The ESCC OR for ‘very hot’ compared to ‘hot’ porridge consumers was 1.65 (95% CI: 1.06,

2.58) in Malawi. In Tanzania most people (97% of both cases and controls) consumed porridge at a ‘hot’ temperature, precluding comparison between categories. However, compared to those who

waited more than 5 min, those who consumed porridge within 2 min had an increased risk of ESCC with ORs of 2.12 (95% CI: 1.22, 3.69) and 2.21 (95% CI: 1.36, 3.58) in Malawi and Tanzania

respectively (Table 2). In total, 27% of porridge consumers reported burning their mouth at least once per month and those who burnt themselves three times or more per month had a 1.9-fold

(1.1–3.2) increase in ESCC risk relative to porridge consumers who did not burn themselves. In Table 2, we note that for most exposure metrics, categories with higher thermal injury were

associated with increased ESCC risks in a monotonic increasing fashion for categories which had a sufficient number of participants. The only exception to this was a U-shaped association in

Malawi, where ‘warm’ compared to ‘hot’ was expected to be protective but it had an OR 1.59 (95% CI: 0.98, 2.60) (Fig. 2) which was not significant at the 5% level. Upon further post hoc

investigations, one possible explanation for this U-shape was interviewer differences in the temperature distributions which could not be adjusted for because some interviewers exclusively

interviewed cases (Supplementary Table S3). When restricting the analysis to the two main interviewers who interviewed both cases and controls (176 cases excluded), ‘warm’ compared to ‘hot’

drinkers had an OR 0.87 (95% CI: 0.51, 1.46) which was in line with the anticipated trend (Supplementary Fig. S2). Similarly, the reduced OR associated with one compared to zero burns was

completely attenuated to the null. These latter subset analyses are purely exploratory, especially because the 95% CIs in both instances include 1, thus variations in the ORs may purely have

occurred due to random variation. Further, positive associations with ESCC risk were seen for all other thermal exposure metrics regardless of the interviewer combination. As seen in Table

2, the most common category often varied between countries but in general positive trends of higher ESCC risk with greater potential thermal injury were observed. Thus, to gain statistical

power, trends were fitted per unit increase in the ordered categories (Table 3). Overall, the trends for all four thermal injury metrics were highly consistent between Malawi and Tanzania.

Notably, the steepest gradient was observed for speed (OR 1.76 per category), then waiting time (OR 1.55) before drinking, then reported temperature (OR 1.33) and mouth burning (OR 1.19).

For mouth/tongue burning, one burn per month was associated with a 7% (95% CI: 2–12) increase in ESCC risk. Similar positive associations across these metrics were explained by positive

correlations among them. These were strongest for temperature and waiting time (Spearman’s correlation coefficient = 0.55, _P_ < 0.001). Thus, for a more complete thermal exposure index

composed of the sum of the temperature, speed, waiting time and mouth/tongue burning category scores. Figure 3 illustrates the make-up of this score (Fig. 3a), as well as its association

with ESCC risk (Fig. 3b). The higher the composite score, the higher the ESCC risk. A unit increase in the score (in the range 1–12) had an ESCC OR of 1.22 (95% CI: 1.14, 1.30) in pooled

analyses. This estimate was very similar to that obtained using a random-effects meta-analytic approach: OR 1.20 (1.12, 1.29) and there was no evidence of between-country heterogeneity (P =

0.29). In the pooled analysis, a thermal exposure composite score of 9 or more, compared to 3, was associated with a 4.6 (2.1, 10.0) fold increase in ESCC risk and strengthened further after

restriction to the main interviewers in Malawi (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table S5). The distribution of the composite score for controls is also depicted visually (Supplementary Fig. S3).

The composite score was also used to investigate potential effect modifiers. There was no evidence of effect modification by sex (_P_ = 0.73), or age (_P_ = 0.57). For alcohol and tobacco as

effect modifiers, the thermal exposure score had a stronger effect in alcohol and tobacco consumers in Malawi, but in abstainers in Tanzania (Table 3). Compared to their counterparts who

drank black tea, milky tea drinkers had lower ESCC risks in Tanzania (OR 0.51 (95% CI: 0.33, 0.78)), whereas the opposite was seen in Malawi where milky tea drinkers had a 2.10-fold (95% CI:

1.50, 2.95) increased ESCC risk in Malawi. The higher risk for milky tea drinkers in Malawi held when restricting to the two main interviewers in that country (not shown). Further, in

Malawi, drinking over 600 mL of tea per day compared to <200 mL was associated with increased ESCC risk: ORs were 4.16 (95% CI: 2.17, 8.00) and 2.73 (95% CI: 1.67, 4.46) in the hot and

cooler seasons respectively (Supplementary Table S4). DISCUSSION PRINCIPAL FINDINGS Primary prevention strategies for esophageal cancer are needed in Africa because the prognosis is

extremely poor and this disease kills 26,000 people per year [1]. If thermal injury to the oesophagus is implicated, it may represent a modifiable factor with an easy to communicate

prevention message. In the current analysis, we presented findings from Malawi and Tanzania regarding thermal exposures from the consumption of hot tea, coffee and porridge and ESCC risk. We

found a consistent pattern across countries, ages and sexes, whereby ESCC risk was increased for higher consumption temperature, shorter time from serving to consumption, faster consumption

speed and mouth/tongue burning from hot beverage/porridge consumption. Based on these four measures, we developed a composite thermal exposure index with a score ranging from 1 to 12. This

index was strongly associated with ESCC risk, reaching an OR of 4.6 (2.1–10.0) for scores of ≥9 vs 3. The score thus provides an improved thermal exposure metric for future studies, for risk

assessment and importantly provides evidence of a dose–response relationship. In relation to other characteristics of hot drink/porridge consumption, we did not observe consistent

associations of ESCC risk with the age consumption commenced, but there was a suggestion of higher risk with larger volumes of consumption in Malawi. Consumers of black compared to milky tea

had an increased ESCC risk in Tanzania, whereas the opposite was seen in Malawi. Effect modification by alcohol and tobacco were also not consistent between countries. The results from the

range of thermal exposure measures emphasise the importance of ascertaining both temperature and speed of consumption. These results are in line with observations that the intra-esophageal

liquid temperature (IELT) [18] is affected as much by the sip temperature as by the sip volume because a greater speed of consumption must imply many small sips at a higher temperature or

fewer larger sips. Interestingly, the 4-category exposure metric “speed of drinking” had the strongest association with ESCC risk and this is the metric where people can directly compare

when they finish drinking compared to their peers, whereas one uncommonly directly experiences the temperature of a peer’s drink. The composite index combining four thermal exposure measures

also benefits from reduced measurement error compared to any single measure, as can be seen from the narrower confidence intervals. Thus, in future studies, whilst real measurements of

temperature and sip volume throughout the drinking experience are recommended if they are feasible and affordable, we recommend to include the range of exposure metrics included here for an

improved thermal exposure assessment. We previously hypothesised that consumption of milky tea (50% water, 50% full-fat milk) was an ESCC risk factor in Tanzania, based on the observation

that milky tea was consumed hotter and cooled at a slower rate than black tea [19]. However, in this study in Tanzania, a lower ESCC risk was found among milky tea drinkers, which was

partially but not fully due to milky tea drinkers drinking at lower thermal exposure levels. If the liquids had the same thermal energy, energy transfer to the oesophagus from milky tea

might occur at a lower rate than from black tea [19]. On the other hand, the greater injury would be expected due to the fat content of milk, as seen in studies of skin burns in children

[26]. Thus, the reason why milky tea drinkers in Tanzania, in the present study, had lower ESCC risk remains an open question. In contrast, in Malawi, those who consumed milky tea had an

elevated ESCC risk compared to black tea drinkers—a finding which was not influenced by the interviewer effect. The different type of milk used in the two countries (fresh in Tanzania and

processed/powdered in Malawi) might explain these differences, through a biological effect or a confounding bias due to a socially-patterned factor or residual confounding. In particular, in

Malawi the habitual tea type had a strong social gradient whereby groups with a higher wealth status are more likely to drink milky tea. These observations require further study in other

African studies. COMPARISON WITH OTHER STUDIES Our findings are consistent with several previous observations from African and other settings. From ESCCAPE Kenya, where tea consumption is

most prevalent, we previously reported similar findings for self-reported temperature [18]. A case–control study in Iran also found an association with self-reported temperature and waiting

time [27] which were consistent with objective temperature measurements in a prospective design [16]. Mouth burning was relatively rare in Tanzania, in contrast to its habitual occurrence in

some Asian settings [17]. In Malawi, mouth/tongue burning was more frequent, with 16% of controls reporting at least three burns per month and ESCC risk increased with more frequent mouth

burning. This positive finding for burn frequency contrasts to the lack of evidence of an association in Kenyan [18] and previous Tanzanian studies [10]. However, the Kenyan study combined

‘do not know’ and ‘no’ burns and the Tanzanian study ascertained ever/never burns. Thus, the improved exposure assessment for the frequency of mouth burning in the present study may be an

important factor to reveal the increased ESCC risk. Further, a reduced odds ratio for one vs no monthly burns was likely due to the interviewer imbalance as those who burnt once per month

had higher thermal exposures of the other three metrics. Pain receptors are activated at high temperatures to protect the consumer from incurring more pain/thermal injury [28]. Finally, the

increased risk with greater drinking volumes in Malawi are also consistent with those from Iran, where hot beverage volumes can also be very large [16]. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS The major

strengths of the present investigation include the detailed exposure assessment for thermal exposures during hot beverage/food consumption, with several metrics, intensity-graded, assessed

across a range of hot drinks and porridge. This allowed for investigations of dose–response associations, consistency across metrics and the generation of a more robust thermal exposure

score with a greater exposure range. This exposure metric was found to be strongly associated with ESCC risk in a positive dose–response fashion. Nevertheless, a potential limitation

inherent in the case–control study design is recall bias [29]. Cases with EC had more time to ponder the circumstances surrounding why they developed the disease. Their recall for factors

like their consumption and perception of hot beverages/food may have changed due to developing the disease and suffering from dysphagia due to it. However, hot beverage drinking is not an

established risk factor nor a highly suspected one often discussed in these communities. As positive associations were also observed in prospective studies and in studies of esophageal

cancer precursors [30, 31], it is unlikely that our overall findings would have been entirely explained by such a recall bias. A further limitation is between-person variability in the

perception of the thermal exposure metrics in the absence of absolute measurements, which would lead to exposure misclassification which may have attenuated results. Finally, there were

differences between interviewers in the distribution of thermal metrics, as already seen in ESCCAPE Kenya [18]. This effect was compounded by the lack of a balanced number of cases and

controls interviewed by each interviewer which we should have identified during the study implementation phase. Furthermore, the range of thermal injury circumstances ascertained may not

have been complete. In addition to porridge (a cooked watery maize flour mixture), the staple crop maize is consumed as a hot cooked stiff dough-like food, known as _nsima_, _pap_, _sadza_

and _ugali_, depending on country/region. This was not captured in the present study. Other generic strengths of the ESCCAPE case–control studies are the histologically confirmed diagnosis

of most ESCC cases, reducing outcome misclassification. Additionally, whilst selection bias is often a problem in cancer case–control studies, especially in LMICs due to differences in

sociodemographic factors and/or urban/rural residential location between cases and controls, bias would only be introduced if thermal exposures were associated with these factors. This is

not a major concern for thermal exposure as in this and previous studies in East Africa, there are no suggestions that there is a social/residential gradient of hot beverage consumption

temperatures/volumes. BIOLOGICAL PLAUSIBILITY AND PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS Chronic thermal injury to the oesophagus is a plausible carcinogen due to several related observations. First,

concerning other tissues, for the skin, severe thermal injuries leading to burn scars associated with Marjolin’s ulcer can lead to squamous cell carcinomas. In the oesophagus, acute

discomfort after consumption of extremely hot/boiling beverages manifests as candy-cane oesophagus upon endoscopic examination, which is reversible but does illustrate localised inflammation

of this tissue at high consumption temperatures. Whilst habitual consumption is typically at lower temperatures, this chronic habit might lead to repeated irritation of the esophageal

mucosa or an altered esophageal microbiome. Inflammation can lead to the endogenous production of reactive nitrogen species including nitrosamines. Alternatively, a damaged mucosa may expose

the epithelium to other carcinogens. Further, a higher prevalence of p53 mutations (G:C to A:T mutations at CpG sites) has been found in esophageal tumours in patients with greater thermal

exposures [32]. Primary prevention strategies for ESCC in Africa are needed. To date, a clear role of alcohol and tobacco has been established in some African settings and especially in men,

but for the substantial proportion of abstainers from these habits, other measures are needed. The present findings indicate that the thermal injury pathway may be a significant contributor

to ESCC risk, as consumption of hot beverage/food is commonplace in adults, thus cancer control plans should consider advice to reduce this exposure [6]. Lowering the beverage/food

consumption temperature, allowing beverages to cool, sipping slowly and ensuring not to burn oneself whilst consuming hot food and drink are advisable. Fortunately, these are cheap easy

messages to convey. Future research is needed to evaluate whether individuals are willing to change their habits. Finally, a research gap remains as to how early in life thermal injuries

might commence, especially in settings where children consume tea from very young ages and given the unusually large burden of young ESCC cases in East Africa. DATA AVAILABILITY Data are

available and can be accessed via collaboration with IARC (https://esccape.iarc.fr/en/Contact). REFERENCES * Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al.

Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. * Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.

Cancer statistics, 2020. CA: A Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. Google Scholar * Smyth EC, Lagergren J, Fitzgerald RC, Lordick F, Shah MA, Lagergren P, et al. Oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Dis

Prim. 2017;3:17048. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Wondimagegnehu A, Hirpa S, Abaya SW, Gizaw M, Getachew S, Ayele W, et al. Oesophageal cancer magnitude and presentation in Ethiopia

2012-2017. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0242807. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Ferndale L, Aldous C, Hift R, Thomson S. Gender differences in oesophageal squamous cell

carcinoma in a South African Tertiary Hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7086. Article PubMed Central Google Scholar * McCormack VA, Menya D, Munishi MO, Dzamalala C,

Gasmelseed N, Leon Roux M, et al. Informing etiologic research priorities for squamous cell esophageal cancer in Africa: a review of setting-specific exposures to known and putative risk

factors. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:259–71. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Van Loon K, Mwachiro MM, Abnet CC, Akoko L, Assefa M, Burgert SL, et al. The African Esophageal Cancer

Consortium: a call to action. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–9. PubMed Google Scholar * Menya D, Kigen N, Oduor M, Maina SK, Some F, Chumba D, et al. Traditional and commercial alcohols and

esophageal cancer risk in Kenya. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:459–69. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Menya D, Maina SK, Kibosia C, Kigen N, Oduor M, Some F, et al. Dental fluorosis and

oral health in the African Esophageal Cancer Corridor: findings from the Kenya ESCCAPE case-control study and a pan-African perspective. Int J Cancer. 2019;145:99–109. Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mmbaga EJ, Mushi BP, Deardorff K, Mgisha W, Akoko LO, Paciorek A, et al. A case–control study to evaluate environmental and lifestyle risk factors for

esophageal cancer in Tanzania. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30:305–16. * Mmbaga BT, Mwasamwaja A, Mushi G, Mremi A, Nyakunga G, Kiwelu I, et al. Missing and decayed teeth, oral

hygiene and dental staining in relation to esophageal cancer risk: ESCCAPE case-control study in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. Int J Cancer. 2020;148:2416–28. * Vizcaino AP, Parkin DM, Skinner ME.

Risk factors associated with oesophageal cancer in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:769–73. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Asombang AW, Kayamba V, Lisulo MM,

Trinkaus K, Mudenda V, Sinkala E, et al. Esophageal squamous cell cancer in a highly endemic region. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2811–7. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Mwachiro MM, Pritchett N, Calafat AM, Parker RK, Lando JO, Murphy G, et al. Indoor wood combustion, carcinogenic exposure and esophageal cancer in southwest Kenya. Environ Int.

2021;152:106485. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, Lauby-Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, et al. Carcinogenicity of drinking

coffee, mate, and very hot beverages. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:877–8. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Islami F, Poustchi H, Pourshams A, Khoshnia M, Gharavi A, Kamangar F, et al. A

prospective study of tea drinking temperature and risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2020;146:18–25. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yu C, Tang H, Guo Y, Bian

Z, Yang L, Chen Y, et al. Hot tea consumption and its interactions with alcohol and tobacco use on the risk for esophageal cancer: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med.

2018;168:489–97. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Middleton DR, Menya D, Kigen N, Oduor M, Maina SK, Some F, et al. Hot beverages and oesophageal cancer risk in western

Kenya: findings from the ESCCAPE case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:2669–76. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Munishi MO, Hanisch R, Mapunda O, Ndyetabura T,

Ndaro A, Schüz J, et al. Africa’s oesophageal cancer corridor: Do hot beverages contribute? Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:1477–86. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Mwachiro MM, Parker RK, Pritchett NR, Lando JO, Ranketi S, Murphy G, et al. Investigating tea temperature and content as risk factors for esophageal cancer in an endemic region of Western

Kenya: validation of a questionnaire and analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon content. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;60:60–6. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * De Jong UW,

Day NE, Mounier-Kuhn PL, Haguenauer JP. The relationship between the ingestion of hot coffee and intraoesophageal temperature. Gut. 1972;13:24–30. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Wolf LL, Ibrahim R, Miao C, Muyco A, Hosseinipour MC, Shores C. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy in a public referral hospital in Lilongwe, Malawi: spectrum of disease and associated

risk factors. World J Surg. 2012;36:1074–82. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * White RE, Abnet CC, Mungatana CK, Dawsey SM. Oesophageal cancer: a common malignancy in young

people of Bomet District, Kenya. Lancet. 2002;360:462–3. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Come J, Castro C, Morais A, Cossa M, Modcoicar P, Tulsidâs S, et al. Clinical and pathologic

profiles of esophageal cancer in Mozambique: a study of consecutive patients admitted to Maputo Central Hospital. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–9. PubMed Google Scholar * Breslow NE, Day NE.

Statistical methods in cancer research. Volume I - The analysis of case-control studies. IARC Sci Publ. 1980:5–338. * Aliosmanoglu I, Aliosmanoglu C, Gul M, Arikanoglu Z, Taskesen F, Kapan

M, et al. The comparison of the effects of hot milk and hot water scald burns and factors effective for morbidity and mortality in preschool children. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2013;39:173–6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Islami F, Pourshams A, Nasrollahzadeh D, Kamangar F, Fahimi S, Shakeri R, et al. Tea drinking habits and oesophageal cancer in a high risk area in

northern Iran: population based case-control study. BMJ: Br Med J. 2009;338:b929. Article Google Scholar * Gadhvi M, Waseem M. Physiology, sensory system. 2019. Book Physiology, Sensory

System. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. * Kopec JA, Esdaile JM. Bias in case-control studies. A review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1990;44:179–86. Article CAS PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Chang-Claude JC, Wahrendorf J, Liang QS, Rei YG, Munoz N, Crespi M, et al. An epidemiological study of precursor lesions of esophageal cancer among young

persons in a high-risk population in Huixian, China. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2268–74. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Islami F, Poustchi H, Pourshams A, Khoshnia M, Gharavi A, Kamangar F, et al.

A prospective study of tea drinking temperature and risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2019;146:18–25. * Abedi-Ardekani B, Kamangar F, Sotoudeh M, Villar S, Islami F,

Aghcheli K, et al. Extremely high Tp53 mutation load in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Golestan Province, Iran. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e29488. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Team ESCCAPE Malawi and Tanzania: A Mwasamwaja, I Kiwelu, R Swai, G Kiwelu, S Mustapha, E Mghase, A Mchome, R Shao, E Mallya, K Kilonzo, G

Liomba, A Kamkwatira, R Nyirenda, P Noah, J Mallewa and L Masamba. ESCCAPE would like to acknowledge the study interviewers, endoscopy and laboratory support: Mary Suwedi, Thandiwe Solomon,

Rose Malamba, Mercy Kamdolozi, Godfrey Mushi, Theresia Namwai, Christine Carreira, and the endoscopy teams at the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre, and the Kilimanjaro Christian

Medical Cente, Moshi. We are very grateful and thankful to all participants who took part in this study. FUNDING Fieldwork and analysis were funded by grant 2018/1795 from Wereld Kanker

Onderzoek Fonds (WKOF), as part of the World Cancer Research Fund International grant programme. Drs Gwinyai Masukume and Clement Narh were supported by the UK Medical Research Council for

cancer capacity building in Africa. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Environment and Lifestyle Epidemiology Branch, International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health

Organization, Lyon, France Gwinyai Masukume, Daniel R. S. Middleton, Clement T. Narh, Joachim Schüz & Valerie McCormack * Kilimanjaro Clinical Research Institute, Kilimanjaro Christian

Medical Centre and Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College, Moshi, Tanzania Blandina T. Mmbaga, Gissela Nyakunga-Maro & Alex Mremi * Malawi College of Medicine, Blantyre, Malawi

Charles P. Dzamalala, Yohannie B. Mlombe & Peter Finch * School of Public Health, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Hohoe, Ghana Clement T. Narh * Faculty of Epidemiology and

Population Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, UK Steady J. D. Chasimpha * Genomic Epidemiology Branch, International Agency for Research on Cancer, World

Health Organization, Lyon, France Behnoush Abedi-Ardekani * School of Public Health, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya Diana Menya Authors * Gwinyai Masukume View author publications You can

also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Blandina T. Mmbaga View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Charles P. Dzamalala View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Yohannie B. Mlombe View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Peter Finch View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Gissela Nyakunga-Maro View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Alex Mremi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Daniel R. S. Middleton View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Clement T. Narh View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Steady J. D. Chasimpha View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Behnoush Abedi-Ardekani View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Diana Menya View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Joachim Schüz View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Valerie

McCormack View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS BTM, CPD, DM, JS and VM conceived the work which led to the submission. The

first draft of the article was written by and all analyses were performed by GM and VM. VM, BTM, CPD, YBM, PF, GN, DRSM, CTN, SJDC, DM, JS and VM revised the manuscript. BAA provided

pathology expertise through the ESCCAPE fieldwork and alongside all authors, interpreted the results. All authors approved the final version. CORRESPONDING AUTHORS Correspondence to Gwinyai

Masukume or Valerie McCormack. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for

Research on Cancer/World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policies or views

of these organisations. ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE The study received ethical approval from the IARC Ethics Committee (IEC 14/15) and Institutional Review Boards for each

site at which the study was conducted: Tanzania: the National Institute for Medical Research Tanzania (NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol.IX/1994) and the Tumaini University Kilimanjaro Christian Medical

University College (830); Malawi: the National Health Sciences Research Committee (NHSRC 17/01/1712). Informed consent, signed or thumbprint, was provided by all participants. CONSENT TO

PUBLISH Informed consent, signed or thumbprint, was provided by all participants. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims

in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION REQUESTED REPRODUCIBILITY CHECKLIST SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is

licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give

appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in

this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative

Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a

copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Masukume, G., Mmbaga, B.T., Dzamalala, C.P. _et al._ A

very-hot food and beverage thermal exposure index and esophageal cancer risk in Malawi and Tanzania: findings from the ESCCAPE case–control studies. _Br J Cancer_ 127, 1106–1115 (2022).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01890-8 Download citation * Received: 22 November 2021 * Revised: 30 May 2022 * Accepted: 08 June 2022 * Published: 29 June 2022 * Issue Date: 05 October

2022 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01890-8 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable

link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(714x419:716x421)/daniel-radcliffe-125dea92f61b46678ecc830863a48e46.jpg)