- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Radiation-induced xerostomia can result in increased caries incidence, necessitating more dental extractions and a resultant increased risk of debilitating

osteoradionecrosis (ORN). Patients undergoing head and neck radiotherapy are routinely treated with a topical preventative regime consisting of fluoride and CPP-ACP (Tooth Mousse). There is

limited evidence specifically relating to fluoride prevention regimes in head and neck cancer patients. Other novel remineralising aids using calcium and phosphate have been proposed for use

in head and neck cancer patients, but again, there is limited evidence. AIMS To retrospectively analyse head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy and placed on a

fluoride/CPP-ACP prevention regime at a single institution. To assess the incidence of caries, extractions and ORN. MATERIALS AND METHODS Case records for 95 patients were retrospectively

assessed. This involved review of paper and computerised clinical notes, correspondence letters and radiographs. RESULTS The mean number of carious teeth was 6.63 (SD 6.81) and the mean

number of extractions was 4.88 (SD 5.84). The teeth most frequently affected by caries and extractions were the mandibular incisors, and 28.4% of patients developed ORN (81.5% of cases

occurring in the mandible). CONCLUSION Development of caries and extraction was a very common event. There is a need for further research into the efficacy of topical prevention regimes. KEY

POINTS * Retrospective case series from a single unit identifying cases of caries, extractions and osteoradionecrosis in head and neck cancer patients. * Highlights a lack of high-quality

research in fluoride prevention programmes in this group of patients. * Highlights the need for further research to assess the efficacy of fluoride prevention regimes in head and neck cancer

patients and includes a suggested template. You have full access to this article via your institution. Download PDF SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS THE DENTAL MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS

IRRADIATED FOR HEAD AND NECK CANCER Article Open access 09 June 2023 CONSEQUENCES OF HYPOSALIVATION IN RELATION TO CANCER TREATMENT AND EARLY MANAGEMENT OF RADIATION-INDUCED CARIES: CASE

REPORTS Article Open access 08 November 2024 THE ROLE OF PRIMARY DENTAL CARE PRACTITIONERS IN THE LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS TREATED FOR HEAD AND NECK CANCER Article Open access 11

November 2022 INTRODUCTION It is estimated that 43-85% of patients with head and neck cancer (HANC) will be treated with radiotherapy.1 Ninety percent of patients with HANC have dental

pathology2 and over 80% of HANC patients suffer acute oral complications as a result of radiation therapy.3 Other treatment methods (surgery and chemotherapy) are also associated with

significant oral side effects.4,5 It has long been known that radiotherapy to the head and neck region is associated with an increased risk of developing dental caries.6 The caries seen in

HANC can be seen as both a direct and indirect effect of the various treatments provided and not simply a direct result of radiation.7 An increase in caries due to radiation-induced

xerostomia, often compounded by dietary changes towards refined cariogenic supplements and food, predisposes patients to dental extractions and osteoradionecrosis (ORN) which can have a

significant long-term impact upon a patient's wellbeing. Patients undergoing radiotherapy to the head and neck region at our Dental Hospital are routinely advised to: * Brush teeth for

two minutes with a fluoride toothpaste * After tooth brushing, apply Tooth Mousse with a finger around the teeth. Spit out any excess and leave without rinsing for five minutes * After Tooth

Mousse, apply a pea-sized amount of high-fluoride toothpaste (Duraphat 5000) into a soft splint (made by the dentist) and place in the mouth for 30 minutes every day. A potential barrier to

good compliance is that patients have to pay for Tooth Mousse. In addition, GDPs are unable to provide repeat prescriptions, therefore making it harder for patients to obtain a regular

supply of high-strength fluoride toothpaste. Instead, patients have to rely on GMPs for this service. Although there is strong evidence for the efficacy of topical fluoride in preventing

dental caries by aiding remineralisation/preventing demineralisation,8,9,10,11 there is limited evidence specifically related to fluoride prevention regimes in HANC patients. Despite this,

topical fluoride prevention regimes are widely recommended in this cohort (Box 1). Due to radiation-induced hyposalivation seen in HANC patients, there are less calcium and phosphate ions

available to aid remineralisation and the benefit of fluoride alone is likely to be limited.15 As a result of this, other remineralising aids incorporating calcium and phosphate have been

proposed for use in HANC patients,16,17 but again, there is limited evidence for their efficacy.18,19 Unfortunately, it seems that there is an inherent difficulty in obtaining high-quality

evidence in this cohort of patients. One study showed that over 50% of irradiated HANC patients are lost to follow-up at 7.5 months.20 In addition, there is only limited incidence data on

dental caries in post-radiation HANC patients.21 BOX 1 EXAMPLES OF SOME RECOMMENDED TOPICAL PREVENTATIVE REGIMES * Daily topical fluoride prevention (Duraphat 5000) in custom trays or

brushed on and daily 0.05% fluoride mouthwash. Daily use of GC Tooth Mousse2 * Fluoride mouthwash, high-concentration fluoride toothpaste and fluoride applicator trays. Tooth Mousse

recommended but not specified when or how often. Chlorhexidine gel in trays for five minutes a night over two weeks and repeated every three months12 * Brush with Duraphat 5000 (5,000 ppm)

twice daily. Apply pea-sized amount of Duraphat 5000 to soft splints for 30 minutes daily (Tooth Mousse applied with a finger recommended for five minutes beforehand). Use 0.05% fluoride

mouthwash (alcohol-free) for one minute daily at a separate time13 * Duraphat 2800 or 5000 twice daily. Use of remineralising toothpaste twice daily. Fluoriguard 0.05% mouth rinse once daily

at a different time to tooth brushing. Fluoride trays used for ten minutes twice a day with Duraphat toothpaste or remineralising toothpaste. Fluoride varnish application twice a year.14

METHODS HRA/NHS REC ethical approval was sought through a formal NHS ethical approval process (19/EE/0108). Clinical records were requested for patients who had received custom-made fluoride

application trays since 2009 (when computerised records began) up until January 2018. This list was used to identify HANC patients (who had received fluoride trays) so that their clinical

records could be assessed. The January 2018 cut-off was chosen to ensure there was potential for a follow-up time of at least one year. A sample size calculation was not carried out as the

entire population available was assessed. Only patients 18 years or older were assessed and a minimum follow-up time of one year was required. It was not possible to record the

patient's age, as the ethics committee were concerned this may lead to identification of the patient. Case records for 95 patients were retrospectively assessed by one person (MB). In

order to piece together the relevant information, many different records had to be assessed. This included paper and computerised clinical records, radiographs, correspondence letters and

consent forms. The majority of the radiographs were OPTs, but there were also some periapical and bitewing radiographs available. Any pre-radiotherapy extractions or carious lesions noted

before radiotherapy commenced were not counted. In addition, carious lesions in each tooth were only recorded once due to difficulties in determining if these were newly carious lesions or

not. Due to lack of clarity within the notes (see limitations), it was not possible to accurately record annual figures for each patient; therefore, overall incidence rates were used. An

encrypted Excel spreadsheet was developed to record the following: * Gender * Follow-up time (years) * Caries (yes or no) * Total number of carious teeth * Extraction (yes or no) * Total

number of extracted teeth * Number of extracted teeth subdivided into: upper molars, upper premolars, upper canine to canine, lower molars, lower premolars, lower canine to canine * ORN (yes

or no) * ORN site (maxilla or mandible and specific site) * Other (to allow free text for any relevant findings). All data were fully anonymised, coded and analysed with descriptive

statistics using SPSS version 22 (IBM). This included frequency distribution, central tendency and dispersion. It was possible to assess the total number of carious lesions, extractions and

ORN for males and females, as well as the frequency at various different sites (molar, premolar or canine to canine). Where cases of ORN were found, efforts were made to identify if this was

a direct result of trauma or a spontaneous occurrence. Attempts were made to qualitatively compare the outcomes with adherence to the fluoride/CPP-ACP protocol and any other potentially

relevant factors such as oral hygiene, smoking status or secondary underlying medical conditions. RESULTS Thirteen patients were excluded as it was not possible to retrieve any data. Three

were found to be duplicate patients and one was not a HANC patient. This left 95 patients in total for which data was collected (Table 1). SPECIFIC TEETH AFFECTED BY CARIES The teeth most

commonly affected by caries were the mandibular incisors and canines (156), followed by the maxillary incisors and canines (140) (Table 2). SPECIFIC TEETH AFFECTED BY EXTRACTIONS The lower

incisors and canines were the most commonly affected by extraction (95) (Table 3). ORN BY SITE The majority of cases of ORN developed in the mandible. There were five cases in the maxilla

(18.5%) and 22 cases in the mandible (81.5%). SUBGROUP ANALYSIS (MALES VS FEMALES) _CARIES AND EXTRACTIONS_ The mean number of carious lesions and extractions in males and females can be

seen in Table 4. ORN The majority of cases of ORN occurred in males (20), compared with seven cases in females. This equates to ORN occurring in 32.3% of males and 21.2% of females

DISCUSSION Compared with the limited number of available studies with which to compare these results, there was an increased incidence of caries, extractions and ORN. Seventy-six percent of

patients had at least one carious tooth or extraction and 28% of patients suffered from ORN. One study22 found caries in only 4% of patients over ten years and 3% over 12-36 months in a

separate study published in the same article. A more recent study23 found caries in 17% of patients assessed over at least 12 months. In this study, there were three outliers who had 28, 24

and 23 carious teeth, respectively. Interestingly, the clinical notes made repeated references to poor oral hygiene and poor compliance with the fluoride regime in these patients. In one

case, this was apparently due to very poor patient motivation. One cited pain with the fluoride mouthwash and being unable to afford Tooth Mousse, and the other patient found the fluoride

trays uncomfortable to wear. In contrast to this, there were three references made in separate patient notes where numerous carious lesions had arrested and the clinician had noted good

compliance with the fluoride/CPP-ACP regime. Regarding extractions, again, compared with the few available studies, there was a higher incidence; one study found that 1.7% of patients

assessed over at least 12 months were reported to require extractions.23 Another study found that 85% of patients did not require post-radiotherapy extractions over three years.24 One

patient in this study who underwent a full lower clearance of ten extractions was unable to have a fluoride tray constructed due to severe trismus. Another who had 28 carious teeth extracted

was noted to have very poor oral hygiene and poor compliance with the fluoride protocol. Two others who had 20 and 15 extractions, respectively, were also noted to have poor compliance with

the fluoride protocol. The lower incisors and canines were most commonly affected by caries and extractions. This likely relates to the fact that there were fewer posterior teeth. This may

be because these teeth are more likely to be extracted before radiotherapy due to the significant radiation doses to which the posterior mandible is exposed in treatment of HANC. This may

therefore lead to a lower threshold for extraction and a move towards a shortened dental arch concept.25 Regarding ORN, much lower incidence rates of 8.2%26 and 7-12%27 have previously been

reported in the literature. In line with both of these studies, the majority of cases were seen in the mandible. This is likely due to both reduced vascular supply in the mandible and

because it is a common tumour site.28 The majority of cases were seen in males (20 vs 7 in females). Of the 27 cases, 20 appeared to be directly linked to a prior extraction. One case was

the result of an infected fixation plate and another followed implant placement. In the remaining cases, no clear cause was identifiable and therefore five cases were assumed to have

occurred spontaneously (that is, no obvious surgical trauma had occurred). Of the 20 cases where teeth were extracted, there was mention of poor oral hygiene in eight of these cases and

seven were noted to be smokers. Due to the limitations of the study, it was not possible to correlate the occurrence of ORN with the time since the extraction was carried out. There was

mention of poor compliance with the fluoride protocol in three of these cases. In addition, one patient was HIV-positive, which may have increased their susceptibility. It is possible that

the increased incidence of caries, extractions and ORN in this study is due to lack of regular follow-up seen for these patients. There was a mean follow-up time of 3.75 years, but the

majority of patients were followed up for only 12 months (although, due to lack of clarity in the notes, it is not possible to say why this was the case). Improved compliance with fluoride

trays has been shown to coincide with more frequent recalls.29 Perhaps increased patient contact would have allowed reinforcement of key oral hygiene instruction messages, including the

fluoride/CPP-ACP prevention regime. In addition, regular recall would theoretically allow carious lesions to be identified earlier, preventing their progression to becoming non-restorable.

The increased incidence of ORN may suggest that more pre-radiotherapy extractions could have been carried out. In addition, it would have been interesting to see which pre-extraction

protocols were followed and the extent to which measures were taken to ensure extractions were as atraumatic as possible, but this was not possible. However, it is important to be cautious

when comparing this study with other published data. To begin with, as previously addressed, there is very limited published research in this area. Of the studies available, there is a lack

of consistency between each one, with numerous potential extraneous variables and methodological flaws making direct comparison difficult. In addition, the retrospective nature of this study

had numerous limitations. LIMITATIONS There were numerous limitations within this study which prevented more detailed statistical analysis and definitive conclusions to be drawn. These

limitations included: * Lack of control group * It was not possible to standardise baseline characteristics, length of observation, precise time to event (caries, extraction or ORN), recall

periods or 'dropout' rate * Risk of detection bias due to the retrospective nature of this study and lack of consistency within the clinical notes regarding what was recorded at

each visit; for example, oral hygiene, adherence to fluoride protocol etc. It was often very difficult to determine exactly why teeth were being extracted due to lack of a clear diagnosis

within the notes * The lack of radiographic images and clinical notes for some patients mean that there may have been an underestimation of extractions and, in particular, carious lesions *

Although there were some bitewing and periapical radiographs, the majority of radiographs assessed were OPTs which are a notoriously unreliable way of identifying caries. Having more than

one person assess the notes would allow for inter-observer reliability to be assessed. It is important that these results are interpreted with caution, given the statistical limitations and

omissions in data available, as is often inevitable in retrospective studies. Despite these limitations, the paper contributes to the existing literature as follows: * It is the only study

looking at HANC patients who have received radiotherapy and a preventative fluoride regime in a UK population. This is important given the variation in epidemiological cohorts and health

service infrastructure in different countries, which mean results may not be directly transferable across geographical locations * To the best of our knowledge, it is the only published

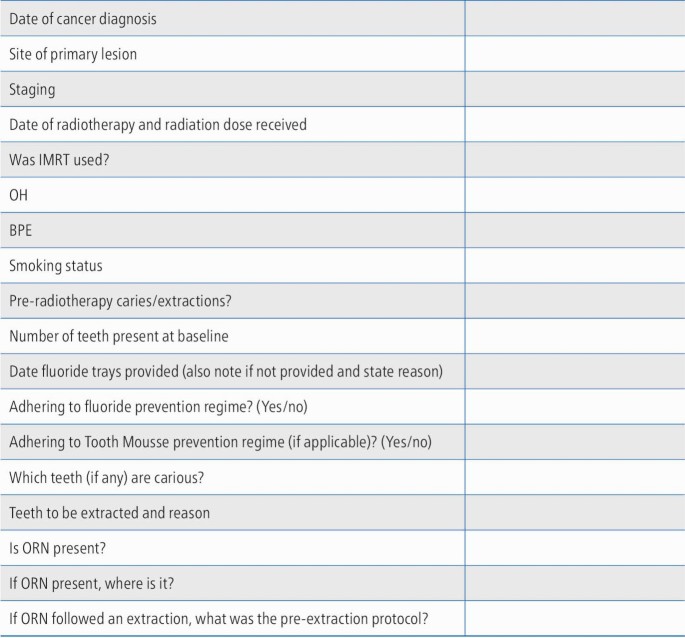

study investigating the use of CCP-ACP and high-strength fluoride (5,000 ppm) in direct succession in HANC patients who have received radiotherapy. FURTHER RESEARCH It would be very

interesting to see similar data from other restorative departments in the UK. The more standardised each data set is, the more external validity these results are likely to have. By having a

more limited but well-controlled dataset for HANC patients and by standardising the data recorded, it is possible that trends between radiotherapy and fluoride/CPP-ACP could be identified,

highlighting areas for future research (Appendix 1). CONCLUSIONS Within the limitations of the study, the following can be concluded: * Development of caries and extraction of teeth was a

very common event for all patients treated with radiotherapy for HANC and assessed in this study. Seventy-six percent of patients had at least one carious tooth or extraction. The overall

mean number of carious teeth was 6.63 (SD 6.81) and overall mean number of extractions was 4.88 (SD 5.84) * The teeth most commonly affected by caries and extractions were the lower incisors

and canines * There was a high incidence of ORN (28.4%) when compared with other figures in the literature and 81.5% of these cases occurred in the mandible * It was not possible to draw

any definitive conclusions regarding the efficacy of fluoride/CPP-ACP in prevention of caries and extractions. There is a need for further research in this area, with more standardised

clinical records to aid statistical analysis. REFERENCES * Cancer Research UK. Head and neck cancers diagnosis and treatment statistics. 2017. Available at

https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/head-and-neck-cancers/diagnosis-and-treatment (accessed March 2020). * Restorative Dentistry

UK. Predicting and managing oral and dental complications of surgical and non-surgical treatment for head and neck cancer: a clinical guideline. 2016. Available at

https://www.restdent.org.uk/uploads/RD-UK%20H%20and%20N%20guideline.pdf (accessed March 2020). * Kufta K, Forman M, Swisher-McClure S, Sollecito T P, Panchal N. Pre-Radiation dental

considerations and management for head and neck cancer patients. _Oral Oncology_ 2018; 76: 42-51. * Kalavrezos N, Scully C. Mouth cancer for clinicians part 10: cancer treatment (surgery).

_Dent Update_ 2016; 43: 375-387. * Kalavrezos N, Scully C. Mouth cancer for clinicians part 12: cancer treatment (chemotherapy and targeted therapy). _Dent Update_ 2016; 43: 567-574. * Del

Regato J A. Dental lesions observed after roentgen therapy in cancer of the buccal cavity, pharynx and larynx. _Am J Roentgenol_ 1939; 42: 404-410. * Kielbassa A M, Hinkelbein W, Hellwig E,

Meyer-Lückel H. Radiation-related damage to dentition. _Lancet Oncol_ 2006; 7: 326-335. * Marinho V C, Higgins J P, Sheiham A, Logan S. Combinations of topical fluoride (toothpastes,

mouthrinses, gels, varnishes) versus single topical fluoride for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. _Cochrane Database Syst Rev_ 2004; DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002781.pub2.

* Marinho V C, Worthington H V, Walsh T, Clarkson J E. Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. _Cochrane Database Syst Rev_ 2013; DOI:

10.1002/14651858.CD002279.pub2. * Marinho V C, Chong L Y, Worthington H V, Walsh T. Fluoride mouthrinses for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. _Cochrane Database Syst

Rev_ 2016; DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002284.pub2. * Walsh T, Worthington H V, Glenny A M, Marinho V C, Jeroncic A. Fluoride toothpastes of different concentrations for preventing dental

caries. _Cochrane Database Syst Rev_ 2019; DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007868.pub3. * McCaul L K. Oral and dental management for head and neck cancer patients treated by chemotherapy and

radiotherapy. _Dent Update_ 2012; 39: 135-140. * Noone J, Barclay C. Head and neck cancer patients-information for the general dental practitioner. _Dent Update_ 2017; 44: 209-215. * Hackett

S, Jones O, Chatzistavrianou D, Newsum D. Head and neck cancer part 3: dental management. _Dent Update_ 2019; 46: 1031-1040. * Deng J, Jackson L, Epstein J B, Migliorati C A, Murphy B A.

Dental demineralization and caries in patients with head and neck cancer. _Oral Oncol_ 2015; 51: 824-831. * Papas A, Russell D, Singh M, Kent R, Triol C, Winston A. Caries clinical trial of

a remineralising toothpaste in radiation patients. _Gerodontology _2008; 25: 76-88. * Sim C P, Wee J, Xu Y, Cheung Y B, Soong Y L, Manton D J. Anti-caries effect of CPP-ACP in irradiated

nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. _Clin Oral Investig_ 2015; 19: 1005-1011. * Raphael S, Blinkhorn A. Is there a place for Tooth Mousse in the prevention and treatment of early dental

caries? A systematic review. _BMC Oral Health_ 2015; 15: 113. * Beacher N G, Sweeney M P. The dental management of a mouth cancer patient. _Br Dent J_ 2018; 225: 855-864. * Toljanic J A,

Heshmati R H, Bedard J F. Dental follow-up compliance in a population of irradiated head and neck cancer patients. _Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod _2002; 93: 35-38. *

Brennan M.T, Spijkervet, F K L, Elting L S. Systematic reviews and guidelines for oral complications of cancer therapies: current challenges and future opportunities. _Support Care Cancer_

2010; 18: 977-978. * Horiot J C, Schraub S, Bone M C _et al._ Dental preservation in patients irradiated for head and neck tumours: a 10-year experience with topical fluoride and a

randomized trial between two fluoridation methods. _Radiother Oncol_ 1983; 1: 77-82. * Frydrych A M, Slack-Smith L M, Parsons R. Compliance of post-radiation therapy head and neck cancer

patients with caries preventive protocols. _Aust Dent J_ 2017; 62: 192-199. * Sulaiman F, Huryn J M, Zlotolow I M. Dental extractions in the irradiated head and neck patient: a retrospective

analysis of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre protocols, criteria, and end results. _J Oral Maxillofac Surg_ 2003; 61: 1123-1131. * Käyser A F. Shortened dental arches and oral

function. _J Oral Rehabil_ 1981; 8: 457-462. * Reuther T, Schuster T, Mende U, Kübler A. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws as a side effect of radiotherapy of head and neck tumour patients-a

report of a thirty year retrospective review. _Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg_ 2003; 32: 289-295. * Nabil S, Samman N. Risk factors for osteoradionecrosis after head and neck radiation: a

systematic review. _Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol _2012; 113: 54-69. * Ray-Chaudhuri A, Shah K, Porter R J. The oral management of patients who have received radiotherapy to the

head and neck region. _Br Dent J_ 2013; 214: 387-393. * Thariat J, Ramus L, Darcourt V _et al._ Compliance with fluoride custom trays in irradiated head and neck cancer patients. _Support

Care Cancer_ 2012; 20: 1811-1814. Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * General Dental Practitioner, Huddersfield, UK Martin Breslin * University Dental Hospital

of Manchester, Restorative, Higher Cambridge Street, Manchester, M15 6FH, UK Carly Taylor Authors * Martin Breslin View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Carly Taylor View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Martin Breslin. RIGHTS AND

PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Breslin, M., Taylor, C. Incidence of new carious lesions and tooth loss in head and neck cancer patients: a

retrospective case series from a single unit. _Br Dent J_ 229, 539–543 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2222-2 Download citation * Received: 06 April 2020 * Accepted: 20 May 2020 *

Published: 23 October 2020 * Issue Date: October 2020 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-020-2222-2 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this

content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative