- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

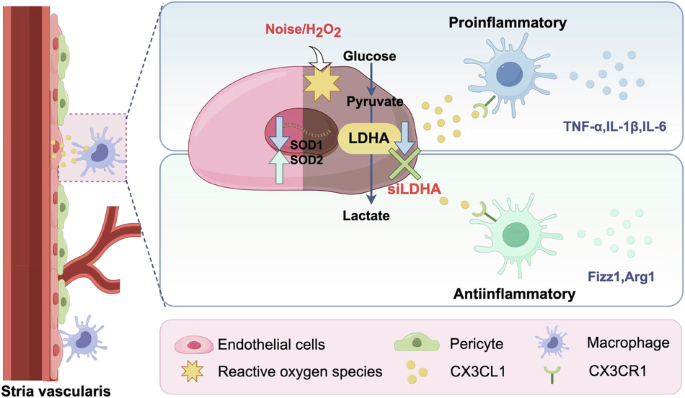

ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to inform the reader of the main principles considered in the management of mild hypodontia involving the absence of one or more maxillary lateral incisors.

With increasing demand and limited resources of hospital dental services, general dental practitioners (GDPs) are required to actively participate in the restorative management of mild

hypodontia cases. The objectives of this article are to discuss the arguments for and against space opening versus space closure and to highlight key points to consider in treatment

planning. The paper discusses advantageous scenarios for both space opening and space closing cases, with the aim of providing the reader with some basic concepts to apply to cases in

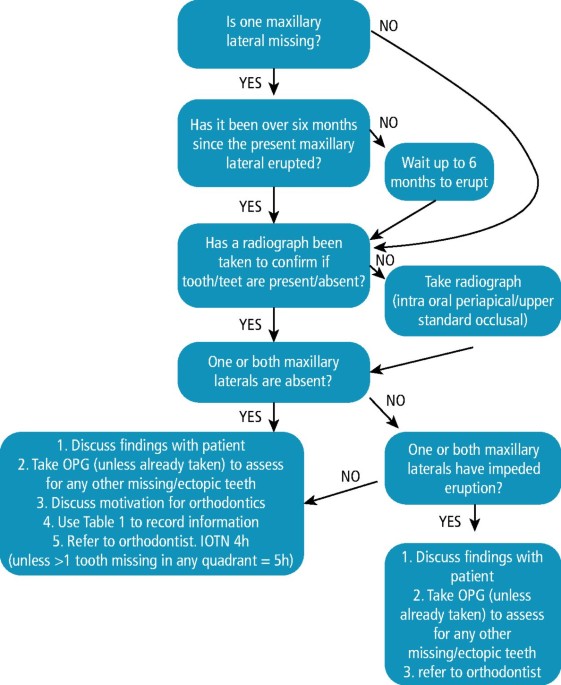

general practice. Included in the paper is guidance for practitioners on the diagnosis of a missing maxillary incisor via the use of a flow chart and table. It is hoped that this paper will

support and enhance the care delivered by GDPs in the restorative management of mild hypodontia patients. You have full access to this article via your institution. Download PDF SIMILAR

CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS TREATMENT OF ABSENT MAXILLARY LATERAL INCISORS: ORTHODONTIC SPACE CLOSURE AND ASSOCIATED PROCEDURES Article 13 September 2024 RESTORATIVE DENTISTRY CLINICAL

DECISION-MAKING FOR HYPODONTIA: PEG AND MISSING LATERAL INCISOR TEETH Article Open access 13 October 2023 RESTORATIVE DENTISTRY CLINICAL DECISION-MAKING FOR HYPODONTIA: RETAINED PRIMARY

MOLARS Article 13 October 2023 KEY POINTS * Highlights the main principles considered in the management of mild hypodontia involving the absence of one or more maxillary lateral incisors. *

Discusses the arguments of space opening versus space closure in the management of missing maxillary lateral incisors. * Guides general dental practitioners with key points of treatment

planning when participating in the restorative management of mild hypodontia cases. INTRODUCTION Hypodontia is the term given to describe the absence of one or more deciduous or permanent

teeth, excluding third molars. In the UK, prevalence is quoted at around 4%,1,2 however, this varies from 4.4-13.4% across different continents.3 The teeth most commonly missing, excluding

third molars, are mandibular second premolars followed by maxillary lateral incisors and maxillary second premolars.3 It has been recognised that there are genetic factors and environmental

factors that can contribute to hypodontia, with the former playing a more significant role.4 Females have been found to be more affected than males5 and it has also been found that over 49

syndromes have associations with hypodontia.6 Those with cleft lip and or palate are also at a higher chance of developing a dentition with missing teeth. Dental anomalies including

microdontia, ectopic permanent teeth, transposition of permanent teeth and submerged deciduous teeth are also often found in patients with hypodontia.4 Missing teeth can impact on

aesthetics, function and ultimately self-esteem. CLASSIFICATION In the literature, hypodontia can be divided into mild, moderate and severe cases. Mild and moderate terms are used to

describe less than three or less than six teeth missing, respectively.7 Severe hypodontia is defined as six or more missing teeth, this is also referred to as oligodontia.8 Anodontia is a

term used to describe the congenital absence of all primary or permanent teeth. Those involved in the multidisciplinary management of hypodontia cases include orthodontists, paedodontists,

restorative dentists and oral surgeons. There are three primary treatment modalities in the management of missing unilateral or bilateral maxillary lateral incisors: * 1. Accept residual

spacing, which may involve retention of the deciduous lateral incisor * 2. Close the space, disguising canines as lateral incisors and first premolars as canines * 3. Open the space and

restore with prostheses. More recently, it has become common for management of the patient to involve both primary and secondary care. Patients may have treatment planning undertaken in a

multidisciplinary environment followed by all or part of the treatment executed in primary care. ASSESSMENT Vigilant observation of eruption patterns and, therefore, early detection of

missing teeth can aid in the space management of developing dentitions. One would anticipate lateral incisors to erupt between the ages of eight to nine years and failure of this should

alert suspicion and warrant radiographic investigation. Premature extractions of primary teeth in crowded jaws may allow some favourable movement of adjacent teeth; however, studies suggest

this rarely results in complete space closure.4 Missing primary teeth is associated with the absence of permanent successors and, therefore, extra vigilance and early referral is

recommended. If hypodontia is suspected this should always be confirmed radiographically. All missing or ectopic teeth, teeth present and details of any other malocclusions should be noted.

The motivation for embarking on orthodontic treatment should also be assessed as well as oral health. A recognised potential implication of missing maxillary lateral incisors is an adjacent

ectopic canine.9 Suspicion of an impacted canine should immediately be addressed with palpation and radiographic examination. Missing lateral incisors would justify an IOTN (Index of

Orthodontic Treatment Need) score 4h and along with more extensive hypodontia, a 5h.10 Additionally, the presence of submerging deciduous molars may generate a 5s score.10 Figure 1

demonstrates a flow chart to follow if missing maxillary laterals are suspected. Table 1 is an example of a checklist of suitable information to obtain at this visit for inclusion in the

referral. ACCEPTING THE SPACE Once a missing maxillary lateral incisor has been identified, it is important to discuss this diagnosis with the patient. If the missing tooth and any spacing

or malpositioning of adjacent teeth are of no concern to the patient, no treatment and acceptance of the space is a valid treatment option. If this option is chosen, close monitoring should

follow until the adjacent canine has erupted to ensure it does not become impacted. A full discussion of the available treatment options and a decision not to treat should be recorded in the

clinical notes. SPACE CLOSURE Closing of the space through orthodontic means can minimise the restorative burden and maintains good periodontal health. Excellent aesthetic outcomes can be

achieved and studies have reported cosmetic results to be better than that offered by space opening.11,12 Some clinicians advocate 'ultra-thin' veneers to disguise canines and

while these may lead to more refined aesthetic outcomes, they are more destructive and undermine a principle argument for space closure.13 This should not be routinely recommended and

certainly not considered at all until completion of gingival maturation. Though space closure can be achieved by orthodontic, restorative or a collaborative approach, multidisciplinary

planning is imperative for successful and predictable outcomes. As a principle, the argument for space closure is to avoid a long-term restorative burden. Orthodontic alignment should be

regarded as the primary treatment, accepting that some restorative modifications may be necessary upon completion of tooth movement. The argument for and against space closure is summarised

in Table 2. Advantageous scenarios for more favourable outcomes via space closure include patients with: * 1. Minor spacing, if restorative management only * 2. A motivation for orthodontics

(caries free and periodontal health) * 3. Unfavourable width spacing, necessitating lengthier and more complex treatment (for example, less than half a unit space) * 4. A favourable

skeletal profile (for example, missing maxillary laterals, Class II Division 1 incisal relationship) * 5. Crowding * 6. Bilateral missing laterals incisors * 7. Favourable aesthetics of

canine for camouflage (colour, shape, gingival margin height) * 8. Spaces not affecting dental symmetry (if no orthodontic involvement) * 9. Small canines unfavourable for adhesive bridge

work. Space closure is further enhanced when the canines are favourably proportioned and both lateral incisors are missing. The masking of unilateral missing laterals can prove difficult.

Due to the discrepancy in size, shape and colour of the canine compared to the present lateral, it can be more difficult to achieve a symmetrical, aesthetic result. The present lateral

incisor may also require significant restoration. A diagnostic wax-up or Kesling set-up can be advisable at this stage to help visualise possible outcomes (Fig. 2). CANINE CAMOUFLAGE When

assessing a canine for its suitability for camouflage, there are four principle obstacles to overcome.15 1. COLOUR Canines often are a different hue to lateral incisors with pronounced

differences in value and chroma. Minimally-invasive dentistry should be the mainstay of management and this should be initially addressed with external tray-based bleaching. Single tooth

bleaching trays can be fabricated to prevent unwanted whitening of the central incisors. Patients should be appropriately consented as the whitening process may take several weeks longer.

With regards to adolescents, General Dental Council (GDC) guidance states that products containing or releasing 0.1-6% hydrogen peroxide can be used in under 18-year-old patients only for

the 'purpose of treating or preventing disease'.16 The unfavourable aesthetic of a canine masking as a lateral incisor is arguably not disease but normal anatomy. There are,

however, a number of negative psychosocial effects that the discolouration can have on an adolescent including negative self-image, bullying and the emotional distress of delaying treatment

to adulthood.17 The use of bleaching to treat unaesthetic, camouflaged canines can eliminate these effects and negate the need to enter the restorative cycle with more invasive treatment, as

discussed later in this article. 2. LENGTH AND WIDTH Canines are wider and longer than lateral and central incisors. Interproximal reduction can be undertaken during orthodontic treatment

with an ideal endpoint aiming for a tooth slightly narrower than the central incisor. The orthodontist should aim to correct the gingival zenith to sit distal to the midline and around 1 mm

beneath the zenith of the central incisor. This may leave the canine tip significantly lower than the central incisor and it may be necessary for the orthodontist to reduce the canine tip as

the tooth moves bodily. The proposed incisal level should be slightly below that of the central incisor. 3. SHAPE Canines are invariably more pointed than incisors, even once the

proportions have been reduced. Correction of this will require the direct addition of composite to square-off the mesial and distal incisal corners. This can be facilitated with a diagnostic

wax-up used to create a matrix allowing ideal palatal contour before veneering composite buccally. Readers are referred to other papers on composite techniques for more information. 4. THE

FIRST PREMOLAR This tooth will become the canine. As first premolar teeth have a palatal cusp and are narrower than canines, they may need adjusting. This could be as simple as a slight

reduction of the palatal cusp, however, the addition of composite to the mesio-buccal aspect may be required to replicate the bulbosity and contour of a canine.18 ORTHODONTIC ASPECTS OF

SPACE CLOSURE Space closure, to bring the canines forward to mask as the missing lateral incisors, is usually achieved with upper and lower arch fixed appliances. The space closure usually

also involves the use of intra-maxillary springs or elastic power chain and/or inter-maxillary elastics. The favourable skeletal profile for space closure of missing lateral incisors is

Class II, usually along with an increased overjet that would benefit from reducing into a class 1 incisor relationship. Canine guidance is not possible when canines are moved to the lateral

incisor position and therefore the occlusal aim is to achieve anterior group function. Also, tooth movement may be slow and occasionally it may be difficult to fully close the space. This is

often due to alveolar bone narrowing and therefore it is harder to move teeth into the shallow bone volume. There is, however, with all orthodontic treatment, a risk of relapse and good

retention needs to be employed after the completion of the active phase of orthodontic treatment.19 From an orthodontic point of view, the aim should be to torque the canine root palatally,

reducing the canine eminence and place the canine root similar to the position that should have been occupied by the permanent maxillary lateral incisor. Other orthodontic movements may

include extrusion of the canine to allow the gingival margins to migrate down to mimic that of a lateral incisor and mesial rotation of the first premolars for aesthetics (Fig. 3). There is

very little data on the longevity of direct bonded restorations to modify canine and premolar shape, but the survival of anterior composites when used to manage tooth wear is very good, with

some evidence of failure emerging after around five to six years.19,20 It must be remembered that failure in this context is not tooth fracture, caries or pulpal death, as would be

anticipated with traditional dentistry, but rather staining and fracture of composites; problems which can be more easily rectified. If compared to more traditional class III and IV

cavities, annual failure rates are reported to be 0.6% and 4.1% (Fig. 4).21 If a patient is not motivated for orthodontic treatment, small spaces can be closed or reduced with restorative

intervention. This can be achieved using composite additions or with more invasive, indirect prostheses, for example, veneers or crowns. Attempts to close larger gaps with restorations can

deliver poor aesthetic results such as, broad 'tombstone' teeth. Fundamentals of smile design should be employed when treatment planning with restorative camouflage.22 SPACE

OPENING An alternative treatment option to manage spaces created by missing laterals is to increase or manipulate the space/spaces to allow aesthetic restoration with a prosthesis (Table 3).

Space opening is only an option for those patients motivated and suitable for orthodontic treatment. The aim of opening or adjusting space in the maxillary lateral region is to create a

single unit space to permit like-for-like replacement of the missing tooth. It is biologically desirable to maintain or create canine guidance to protect the future prostheses. Advocates of

space opening would argue that canine guidance is a more favourable functional outcome and more predictable in the long-term. In addition, prosthetic laterals have superior aesthetics to

that of camouflaged canines. Clinicians must recognise, however, that space closure is not always possible and alternative strategies will be needed.23 The arguments for and against space

opening are summarised in Table 4. Advantageous situations for more favourable outcomes via space opening/alteration include patients with: * 1. Single missing lateral with/without

peg-shaped contralateral incisor * 2. Sufficient enamel on abutment tooth for bonding (if adhesive bridge planned) * 3. Sufficient bone for implant/retained maxillary deciduous lateral

incisor (if implant retained prosthesis planned) * 4. Large or uneven sized spans (for example, 3/4 unit) * 5. A motivation for orthodontics (caries free and periodontal health) * 6. Spaced

dentition * 7. Class III skeletal profile * 8. Canine shape and size unfavourable for camouflage. The ambition of space opening treatment plans should be to create space appropriate to

accommodate a lateral incisor proportionate to the central incisor. Around 7 mm is usually the optimum sized space but this may need to be reduced proportionately if the centrals are

diminutive but well-proportioned. If the planned restorative solution is dental implants, then a minimum space of 7 mm should be achieved in both intra-coronal space and intra-radicular

space. The centrals should also be assessed whereby the width of the crown should be around 80% of the length. If this is not the case, restorative modification of the centrals may need to

be factored into the final treatment plan or the shape modified mid-orthodontic treatment. The average central incisor is 10-11 mm x 8-9 mm. Often in hypodontia cases, incisors are poorly

proportioned and narrower. If, for example, the incisor is 11 mm in length but only 7 mm in width, the orthodontist should aim for an 8 mm space in the lateral position to accommodate the

addition of composite to the centrals as well as the prosthetic lateral. The same may be said of canines; often these teeth benefit from the addition of composite to improve the proportions.

Prior to the debond appointment, it is recommended for the dentist providing restorative treatment to review the spaces that have been created. This is an opportunity to revisit the initial

treatment plan and compare this with the orthodontic result achieved (Fig. 5). Once a suitable sized space has been created, options for restoring the space can be in the form of a

removable prosthesis, conventional or adhesive bridgework, autotransplantation or an implant-retained prosthesis. Partial dentures, although not often the preferred choice, can be a fast and

straightforward treatment option to replace missing maxillary laterals. They also provide the flexibility to alter face height and act as space maintainers in interim treatment planning.15

An orthodontic retainer with laterals incorporated gives immediate rehabilitation and allows time for space assessment and planning. This may be in the form of a traditional Hawley or Essix

retainer. If considering bridgework, it is important to have a thorough assessment of abutment teeth. Conventional bridgework should remain a discussion item in consent terms but should be

avoided unless the canines are heavily restored and protection of remaining tooth structure is sought. In addition, the likelihood of pulpal death is very high in young teeth.24,25

Resin-retained bridges are the bridge of choice yet require sufficient enamel on which to bond for a predictable outcome.26,27 In these authors' opinion, the canine should be the tooth

of choice as there is invariably a good surface area for bonding and the depth of dentine is usually sufficient to prevent metal show through, which may compromise aesthetics. Excellent

long-term retention is essential as de-rotation of the canine may result in compromised aesthetics later in life (Fig. 6). Short clinical crowns and microdont teeth can restrict the amount

of palatal enamel for bonding.15 It is possible however, to increase the amount of enamel available using electrosurgery or formal crown lengthening.9 The central incisors may be used as

abutments yet can be prone to greying of the abutment, resulting in compromised cosmetics. In addition, the alveolar ridge should be examined when deciding upon the shape of the pontic. Site

preparation with electrosurgery or a high speed handpiece with a round coarse diamond bur can help develop the future pontic site and encourage a more natural emergence.28,29 Using such

techniques can ensure good aesthetics and high success rates at five and ten years. Although the success rates of adhesive bridges may appear lower than those of dental implants, one must

remember that resin-bonded bridges offer a simple, inexpensive and elegant solution. The biggest consequence of failure is the embarrassment between bridge debond and the emergency recement

rather than the costly and labour intensive prosthetic and biological complications associated with implantology (Fig. 7). Implants can offer an alternative solution in cases where dentures

or adhesive bridgework are unsuitable or not desired. Implants are usually limited to those over 18 years of age, following the majority of craniofacial growth. Patients considering this

treatment option must have a full assessment of the amount and quality of bone, as well as the angulation of the adjacent teeth and their roots. Due to the lack of alveolar bone in the

endentulous span, it is often necessary for bone augmentation in hypodontia cases.15 Nonetheless, the implant solution is independent and fixed. It also allows restoration of the space with

residual spacing if necessary. Though the implant-based solution is often seen by patients and clinicians alike as the treatment ambition of choice, the lifetime burden of maintenance may

leave adhesive bridges the most predictable options. While survival rates of implant-retained crowns are high, this does not represent any biological or technical complications that can

often occur over the implant lifespan.32 It implies survival rates to be equivalent to success rates, perhaps ill advising patients of the potential problems encountered with implant upkeep,

which often involve significant costs. SUMMARY: KEY POINTS As a GDP, when diagnosing missing maxillary lateral incisors or when assisting in their management it is important to abide by the

following practices: * 1. Be vigilant with eruption patterns * 2. Refer early * 3. Reinforce importance of exceptional oral hygiene * 4. Use diagnostic wax ups * 5. For space opening cases,

review the patient before debond to reassess and adapt treatment plan if necessary * 6. Remember planning and good liaison is key! REFERENCES * Larmour C J, Mossey P A, Thind B S, Forgie A

H, Stirrups D R. Hypodontia − a retrospective review of prevalence and aetiology. Part I. _Quintessence Int _2005; 36: 263-270. * Brook A H. Variables and criteria in prevalence studies of

dental anomalies of number, form and size. _Community Dent Oral Epidemiol _1975; 3: 288-293. * Khalaf K, Miskelly J, Voge E, Macfarlane T. Prevalence of hypodontia and associated factors: a

systematic review and meta-analysis._J Orthod _2014; 41: 299-316. * Al-Ani A H, Antoun J S, Thomson W M, Merriman T R, Farella M. Hypodontia: An Update on Its Etiology, Classification, and

Clinical Management. _Biomed Res Int _2017; 2017: 9378325. DOI: 10.1155/2017/9378325. * Polder B J, Van't Hof M A, Van der Linden F P, Kuijpers-Jagtman A M. A meta-analysis of the

prevalence of dental agenesis of permanent teeth. _Community Dent Oral Epidemiol _2004; 32: 217-226. * Fekonja A. Hypodontia in orthodontically treated children._Eur J Orthod _2005; 27:

457-460. * Rakhshan V. Congenitally missing teeth (hypodontia): A review of the literature concerning the aetiology, prevalence, risk factors, patterns and treatment._Dent Res J (Isfahan)

_2015; 12: 1-13. * Durey K, Cook P, Chan M. The management of severe hypodontia. Part 1: considerations and conventional restorative options._Br Dent J_ 2014; 216: 25-29. * Brin I, Becker A,

Shalhav M. Position of the maxillary permanent canine in relation to anomalous or missing lateral incisors: a population study._Eur J Orthod _1986; 8: 12-16. * Brook P H, Shaw W C. The

development of an index of orthodontic treatment priority. _Eur J Orthod _1989; 11: 309-320. * De-Marchi L M, Pini N I, Ramos A L, Pascotto R C. Smile attractiveness of patients treated for

congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors as rated by dentists, laypersons, and the patients themselves. _J Prosthet Dent _2014; 112: 540-546. * Schneider U, Moser L, Fornasetti M,

Piattella M, Siciliani G. Esthetic evaluation of implants vs canine substitution in patients with congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors: Are there any new insights? _Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop _2016; 150: 416-424. * Zachrisson B U, Rosa M, Toreskog S. Congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors: canine substitution. _Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop _2011;

139: 434, 436, 438. * McDowall R J, Yar R, Waring D T. 2 '2' 1: Orthodontic repositioning of lateral incisors into central incisors. _Br Dent J _2012; 212: 417-423. * Savarrio L,

McIntyre G T. To open or to close space--that is the missing lateral incisor question. _Dent Update _2005; 32: 16-18, 20-22, 24-25. * General Dental Council. Position Statement on Tooth

Whitening. 2016. Available athttps://www.gdc-uk.org/api/files/Tooth-Whitening-Position-Statement.pdf (accessed February 2019). * Greenwall-Cohen J, Greenwall L, Haywood V, Harley K. Tooth

whitening for the under 18-year-old patient. _Br Dent J _2018; 225: 19-26. * Holliday R, Lush N, Chapple J, Nohl F, Cole B. Hypodontia: aesthetics and function part 2: management. _Dent

Update _2014; 41: 891-898. * Hemmings K W, Darbar U R, Vaughan S. Tooth wear treated with direct composite restorations at an increased vertical dimension: Results at 30 months. _J Prosthet

Dent _2000; 83: 287-293. * Gulamali A B, Hemmings K W, Tredwin C J, Petrie A. Survival analysis of composite Dahl restorations provided to manage localised anterior tooth wear (ten year

follow-up). _Br Dent J _2011; 211: E9. * Demarco F F, Collares K, CoelhodeSouza F H _et al. _Anterior composite restorations: A systematic review on long-term survival and reasons for

failure. _Dental Mater _2015; 31: 1214-1224. * Ricketts R M. The biologic significance of the divine proportion and Fibonacci series._Am J Orthod_ 1982; 81: 351-370. * Kokich V O Jr, Kinzer

G A, Janakievski J. Congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors: restorative replacement. _Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop _2011; 139: 435, 437, 439. * Schwartz N L, Whitsett L D, Berry T

G, Stewart J L. Unserviceable crowns and fixed partial dentures: life-span and causes for loss of serviceability._J Am Dent Assoc _1970; 81: 1395-1401. * Walton J N, Gardner F M, Agar J R.

A survey of crown and fixed partial denture failures: length of service and reasons for replacement. _J Prosthet Dent _1986; 56: 416-421. * Djemal S, Stechell D, King P, Wickens J. Long-term

survival characteristics of 832 resin-retained bridges and splints provided in a post-graduate teaching hospital between 1978 and 1993._J Oral Rehabil_ 1999; 26: 302-320. * King P A, Foster

L V, Yates R J, Newcombe R G, Garrett M J. Survival characteristics of 771 resin-retained bridges provided at a UK dental teaching hospital._Br Dent J _2015; 218: 423-428. * Dylina T J.

Contour determination for ovate pontics._J Prosthet Dent _1999; 82: 136-142. * Durey K A, Nixon P J, Robinson S, Chan M F. Resin bonded bridges: techniques for success. _Br Dent J _2011;

211: 113-118. * Pjetursson B E, Tan W C, Tan K, Brägger U, Zwahlen M, Lang N P. A systematic review of the survival and complication rates of resin-bonded bridges after an observation period

of at least 5 years._Clin Oral Implants Res _2008; 19: 131-141. * Pjetursson B E, Brägger U, Lang N P, Zwahlen M. Comparison of survival and complication rates of tooth-supported fixed

dental prostheses (FDPs) and implant-supported FDPs and single crowns (SCs). _Clin Oral Implants Res_ 2007; 18 (SPEC ISS): 97-113. * Beaumont, J, McManus, G, Darcey J. Differentiating

success from survival in modern implantology - key considerations for case selection, predicting complications and obtaining consent. _Br Dent J _2016; 220: 31-38. Download references AUTHOR

INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Mill Hill Dental Clinic, Derby, UK Esme Westgate * Orthodontics, University of Manchester Dental Hospital, Manchester, UK David Waring & Ovais

Malik * Restorative Dentistry, University of Manchester Dental Hospital, Manchester, UK James Darcey Authors * Esme Westgate View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * David Waring View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ovais Malik View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * James Darcey View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to James Darcey.

RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Westgate, E., Waring, D., Malik, O. _et al._ Management of missing maxillary lateral incisors in general

practice: space opening versus space closure. _Br Dent J_ 226, 400–406 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0082-4 Download citation * Published: 22 March 2019 * Issue Date: March 2019

* DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0082-4 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is

not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative