- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Black men are twice as likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer than White men. Raised prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels can indicate an increased risk of

prostate cancer, however it is not known whether PSA levels differ for men of different ethnic groups. METHODS _PubMed_ and _Embase_ were searched to identify studies that reported levels of

PSA for men of at least two ethnic groups without a prostate cancer diagnosis or symptoms suggestive of prostate cancer. An adaptation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used to assess risk

of bias and study quality. Findings were stratified into the following broad ethnic groups: White, Black, Asian, Hispanic, and Other. Data were analysed in a narrative synthesis due to the

heterogeneity of reported PSA measures and methods in the included studies. RESULTS A total of 654 197 males from 13 studies were included. By ethnicity, this included 536 201 White (82%),

38 287 Black (6%), 38 232 Asian (6%), 18 029 Pacific Island (3%), 13 614 Maori (2%), 8 885 Hispanic (1%), and 949 Other (<1%) men aged ≥40 years old. Black men had higher PSA levels than

White men, and Hispanic men had similar levels to White men and lower levels than Black men. CONCLUSIONS Black men without prostate cancer have higher PSA levels than White or Hispanic men,

which reflects the higher rates of prostate cancer diagnosis in Black men. Despite that, the diagnostic accuracy of PSA for prostate cancer for men of different ethnic groups is unknown, and

current guidance for PSA test interpretation does not account for ethnicity. Future research needs to determine whether Black men are diagnosed with similar rates of clinically significant

prostate cancer to White men, or whether raised PSA levels are contributing to overdiagnosis of prostate cancer in Black men. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS PROSTATE CANCER RISK IN

MEN OF DIFFERING GENETIC ANCESTRY AND APPROACHES TO DISEASE SCREENING AND MANAGEMENT IN THESE GROUPS Article Open access 18 December 2021 ETHNIC VARIATION IN PROSTATE CANCER DETECTION: A

FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR USE OF THE STOCKHOLM3 TEST IN A MULTIETHNIC U.S. COHORT Article 08 July 2020 SERUM PSA-BASED EARLY DETECTION OF PROSTATE CANCER IN EUROPE AND GLOBALLY: PAST, PRESENT

AND FUTURE Article 16 August 2022 INTRODUCTION Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer death in males worldwide with 357 000 annual deaths [1].

Incidence and mortality of prostate cancer differ according to ethnicity: each are twice as high in Black males compared to White males in both the USA [2, 3] and the UK [4,5,6], whereas

Asian men in the UK experience lower rates [4,5,6]. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a protein secreted by the prostate gland and is measured through blood testing. PSA can be elevated in

patients with prostate cancer or benign prostate disease; it does not accurately discriminate between the two and the benefits of PSA screening are unclear [7,8,9,10,11]. Evidence on the

diagnostic accuracy of PSA in symptomatic men is focussed on the referred population, and the performance in men consulting primary care is unknown [12]. The most recent systematic review of

the diagnostic accuracy of PSA for prostate cancer in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms found that a PSA threshold of 4 ng/mL had a sensitivity of 0.93 (95% CI 0.88, 0.96)

specificity of 0.20 (95% CI 0.12, 0.33), and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) was 0.72 (95% CI 0.68, 0.76), although this did not factor in patient ethnicity and studies were at high risk of

bias [13]. To assess a patient’s risk of prostate cancer in the USA, doctors are encouraged to use their clinical judgement of a patient’s PSA level in combination with factors that elevate

their risk (such as whether a patient is of Black ethnicity). Patients are then referred for further tests or monitoring if necessary [14]. In the UK, guidance from the National Institute of

Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) provides age-specific PSA thresholds to assess a patient’s risk of prostate cancer [15]. These guidelines recommend that men with a PSA above

age-specific thresholds should be offered investigation and referral for suspected prostate cancer, but does not take into account the patient’s ethnicity. A recent systematic review found

ethnicity to be a considerable source of heterogeneity when assessing age-adjusted PSA reference ranges and concluded ethnicity should be considered when clinically assessing PSA levels

[16]. There is currently no ethnicity specific guidance for interpreting PSA results although previous studies have considered ethnicity-specific PSA thresholds [17,18,19]. Identifying

differences in PSA levels in men of different ethnic groups without prostate cancer could help refine the identification of men who may benefit from investigation for suspected prostate

cancer. This systematic review sought to identify studies that reported PSA levels for different ethnic groups for men without a prostate cancer diagnosis or symptoms suggestive of prostate

cancer and incorporated the findings from these studies into a narrative synthesis to determine the effects of ethnicity on PSA. METHODS PROTOCOL This systematic review closely adhered to

the study protocol which was published on the PROSPERO website on the 29th September 2021 before commencement of abstract screening (reference CRD42021274580) and was conducted in strict

accordance to the PRISMA 2020 reporting guidelines. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA This review aimed to identify studies that reported measures of PSA levels of men without a prostate cancer diagnosis

or symptoms suggestive of prostate cancer for at least two different ethnic groups. Studies that only included PSA values for only one ethnic group were excluded to reduce selection,

design, measurement, and reporting bias. We included observational studies and randomised controlled trials with baseline characteristics, but excluded studies based on cases and matched

controls. Only studies with the full text available and peer reviewed in English were included. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are available in Table 1. SEARCH STRATEGY _PubMed_ and

_Embase_ were searched on the 24th September 2021 and again on the 21st June 2022 to identify studies that reported levels of PSA for at least two ethnic groups. Search terms included

prostate-specific antigen _or_ PSA _and_ ethnicity _or_ ethnic group. To capture all ethnicity or ethnic groups, the search included mESH terms for a number of ancestry groups such as

African, European, Asian, American Native, and Oceanic, mESH terms for Ethnic Groups and Minority Groups, as well as commonly used terms to describe ethnic groups such as African*, Caucas*,

Europ*, Asian*, Indian*, Maori*, Hispanic*, Chinese* etc. The terms White and Black were included if they appeared within three words of ethnic* in attempt to reduce non-specific search

returns. Full search terms can be found in Appendix 1. Endnote X9 was used to automatically detect duplicates which was followed by manual detection by one reviewer. Two reviewers

independently screened abstracts and full texts for eligibility and conflicts were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer. Cohen’s kappa was calculated to assess interrater

reliability. DATA EXTRACTION Data extraction was completed independently by two reviewers and cross-referenced for discrepancies. The following data were extracted: number and age of

patients, country of study, the context in which PSA levels were collected (healthcare records vs PSA test in general population), ascertainment of ethnicity, and PSA measures (median, mean,

centiles, proportion above/below) for each ethnic group. Given that age is a factor in PSA variation, age-stratified or age-adjusted levels were extracted where reported. QUALITY ASSESSMENT

As this systematic review extracted PSA measures from a variety of study designs, an adaptation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for cohort studies was used to assess the quality and risk of

bias of the included studies, addressing the aims of this review rather than the individual aims of the included papers. The adaptation of the Newcastle-Ottawa assessment can be found in

Appendix 2. Two reviewers independently scored each paper based on selection, comparability, and outcome domains for a maximum of nine stars. Conflicts were resolved by discussion. Each

study was then classed as ‘good’, ‘fair’, or ‘poor’ based on the Newcastle-Ottawa thresholds. DATA SYNTHESIS Participants were stratified into the following broad ethnic groups based on the

classification used in the included papers: White (including White, Caucasian, European), Black (Black, African American, non-Hispanic Black), Asian (Asian), Hispanic (Hispanic, Latino,

Mexican-American), and Other (Other, Maori, Pacific Island, Pacific People). Where studies reported more than one summary statistic for PSA values, the summary statistic most comparable with

other extractions was chosen for the final table (most often median and 95th percentile). If statistical significance was not reported, confidence intervals were calculated from the mean

and standard deviation where possible to infer significance. Studies that were assessed as poor quality were considered separately to studies that were assessed as fair or good in a

narrative sensitivity analysis. Due to significant heterogeneity in the reported measures of PSA, meta-analysis was not possible. Therefore, results were collated and summarised into a

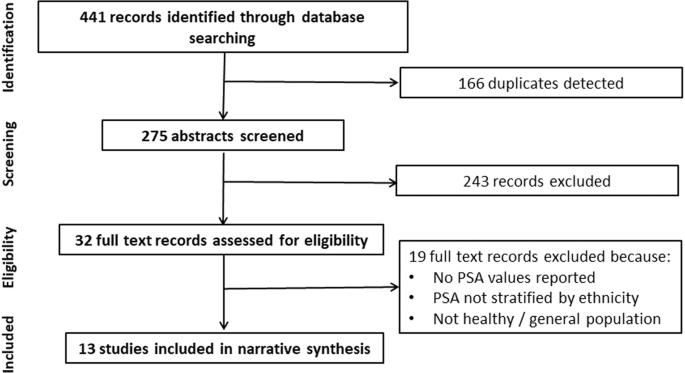

narrative synthesis following previously published guidance [20]. RESULTS DATABASE SEARCH The database search returned 441 studies, from which 166 duplicates and 243 irrelevant studies were

excluded based on title and abstract. This left 32 studies for full-text review, of which 19 studies were excluded and resulted in 13 studies included in the narrative synthesis (Fig. 1).

The level of inter-rater reliability was moderate (0.57, Cohen’s kappa) for abstract screening and substantial (0.64, Cohen’s kappa) for full-text screening. STUDY QUALITY Just over half

(7/13) of the included studies were assessed as high quality (good) using the adapted Newcastle-Ottawa scale, with the remainder rated as poor. The full evaluation of study quality

assessment can be found in Table 2. STUDY CHARACTERISTICS The characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Table 3. A total of 654 197 males aged ≥40 years old from 13 studies

were included, although up to 2 313 of these patients (1 808 White and 705 Black men) may have been duplicated through use of the same datasets. By ethnic group, there were 536 201 White

(82%), 38 287 Black (6%), 38 232 Asian (6%), 18 029 Pacific Island (3%), 13 614 Maori (2%), 8 885 Hispanic (1%), and 949 Other (<1%) males included. Study countries included the USA and

New Zealand. The PSA values from each study are reported in Table 4, stratified by ethnic group. Nine studies stratified PSA values by age, one study adjusted PSA values for age [21], and

three studies did not control for age [17, 22, 23]. PSA levels were summarised by mean (standard deviation (SD)), percentage of men over a certain threshold (1.4 ng/mL and 4.0 ng/mL), median

and interquartile range (IQR), 90th percentile, 95th percentile, and age-adjusted mean with standard error (SE). The most common summary statistic used was median with 95th percentile.

NARRATIVE SYNTHESIS Ten studies reported PSA values for White and Black men, all conducted in the USA. Half of these studies found higher PSA levels in Black men compared with White men [18,

19, 21, 24, 25], one study found the opposite [23], while the remaining four studies found no difference between men of both groups [17, 22, 26, 27]. Of the five studies that did not find

any evidence of differences, or found that White men had higher PSA levels than Black men, four of these studies were rated as poor quality [17, 22, 23, 27]. Incidentally, three of these

studies did not stratify by age [17, 22, 23] and the mean age of White men was greater than Black men in two of these [17, 23]. All of the five studies that compared PSA levels of Hispanic

men to White and Black men were assessed as good quality [18, 19, 21, 24, 26]. One of these studies found fewer Hispanic men experienced PSA values over 4 ng/mL compared to Black men, and

while this was not an age-adjusted or age-stratified calculation, Hispanic men had a higher median age range than Black men [19]. The remaining four studies had a much smaller sample size of

Hispanic men and found no evidence of differences in PSA values between Hispanic and Black men. None of the five studies reported a difference in PSA levels between Hispanic and White men;

indeed, the summary values reported for these men appeared consistently similar across each study. Only two studies reported PSA levels for Asian men, and both found no difference between

Asian men and men of other ethnic groups [18, 28]. Finally, there was no evidence of differences in PSA levels between the Maori and Pacific Island ethnic groups in any of the three studies

that reported PSA levels in New Zealand [28,29,30]. A difference was found in the age-adjusted mean difference between Maori and White men, with significantly higher PSA levels reported for

White men [29]. However, in an almost identical cohort, this difference was not observed in Grey, et al. (2005) when assessing proportions of men with a PSA level above 4 ng/mL [30].

DISCUSSION KEY FINDINGS This systematic review found evidence that Black males had higher PSA levels than White males in the USA, with no published evidence from other countries with

significant Black populations. Multiple studies suggested Hispanic men have similar PSA levels to White men in the USA, with one study reporting lower PSA levels in Hispanic men compared to

Black men. In New Zealand, Maori men were found to have lower levels of PSA than White men and there were no differences between Maori men and Pacific Island men. There was no evidence of

differences between the PSA levels of Asian men and men of other ethnic groups. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS The overarching strength of this study was the inclusion of 654 197 men.

Importantly, studies were only selected if PSA values were collected for men within the same country to control for differences in healthcare systems and inter-country cultures, and

age-stratified or age-adjusted PSA values were meticulously extracted where possible to control for the effects of age. A weakness was the availability of studies limited to the USA and New

Zealand and a considerable underrepresentation of the Asian and Mixed ethnicities, major ethnic groups in many countries. A meta-analysis would have provided further certainty of differences

in PSA values across the ethnic groups, although this was not possible due to the heterogeneity of reported PSA measures. Publication bias may have resulted in a higher number of

publications reporting ethnic differences in PSA values. However, the outcome of four of the included studies was prostate cancer risk or urological outcomes [17, 22, 23, 29], thus any

reported ethnic differences in PSA values from the patient characteristics of these studies should have been free from publication bias. Indeed, Rhodes, _et al_. (2012b) [23] reported higher

PSA levels in Black men compared to White men in their patient characteristics. COMPARISON TO EXISTING LITERATURE Ethnicity was found to be a source of significant heterogeneity in a recent

systematic review assessing age-adjusted reference ranges in apparently healthy men: controlling for ethnicity in 10-year age intervals reduced study heterogeneity by 13% from 99% (_I_2

statistic) [16]. The remaining heterogeneity may have been explained, in part, by differences in inter-country cultures and healthcare systems, which was not controlled for. The study

concluded ethnicity was an important parameter that influenced PSA levels and should be considered when clinically assessing PSA values. In a prostate cancer cohort in the UK including Black

and White men, Black men were found to have higher PSA levels than White men at the point of diagnosis [31]. Despite this, Black men were diagnosed at similar clinical stages and had

similar Gleason scores, and interestingly, preliminary data from the authors suggested there was no difference in prostate cancer mortality between Black and White men [32]. This starkly

contrasts with abundant data from the USA reporting poorer prognosis in Black men [33] which may be attributed to the differences in healthcare systems between the two countries: access to

healthcare in the USA varies significantly by income and deprivation, whereas healthcare in the UK is universally free at point of access. As deprivation levels are higher in Black men in

the USA compared to White men, Black men may be less able or likely to access healthcare [34]. Asian men in the UK were reported to have lower incidence of prostate cancer than White men,

with lower PSA levels at diagnosis and less aggressive disease at presentation [35]. CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS The findings of this systematic review shed some light on PSA levels of men across

different ethnic groups. Further research is needed to determine whether these differences are enough to warrant introducing ethnicity into guidance for interpreting PSA levels, and what the

implications of that may be. The accuracy of PSA for the diagnosis of prostate cancer in different ethnic groups is unknown, as is whether higher PSA levels observed in Black men are due to

higher prevalence of prostate cancer in that group, or whether higher PSA levels in Black men could be contributing to overdiagnosis. Any amendments to current guidance for interpreting PSA

based on ethnicity will need to be carefully assessed with thorough modelling and evaluation taking into account prostate cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis and mortality to ensure it was

reducing, rather than increasing, health inequalities in prostate cancer diagnosis. CONCLUSION Healthy Black men have higher PSA levels than White or Hispanic men, which reflects the higher

rates of prostate cancer diagnosis in Black men. It is not known whether Black men are diagnosed with similar rates of clinically significant prostate cancer to White men, or whether raised

PSA values are contributing to overdiagnosis in Black men. Future research needs to consider the impacts of PSA thresholds in Black men for triggering prostate cancer investigation, and

whether ethnicity specific PSA thresholds could help to reduce the ethnic inequalities in prostate cancer diagnosis. DATA AVAILABILITY Template data extraction forms, data extracted from

included studies, and data used for analysis can be supplied from the corresponding author upon request. REFERENCES * Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et

al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. Article PubMed Google Scholar

* Siegel D, O’Neil M, Richards T, Dowling N, Weir H Prostate Cancer Incidence and Survival, by Stage and Race/Ethnicity — United States, 2001–2017. US Department of Health and Human

Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020;69. * American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2022. 2022. * Office for National Statistics. Mortality from leading

causes of death by ethnic group, England and Wales: 2012 to 2019. 2021. * Cancer Research UK. Prostate cancer statistics. 2022. * Delon C, Brown KF, Payne NWS, Kotrotsios Y, Vernon S,

Shelton J. Differences in cancer incidence by broad ethnic group in England, 2013–2017. Br J Cancer. 2022;126:1765–73. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Tikkinen KAO, Dahm

P, Lytvyn L, Heen AF, Vernooij RWM, Siemieniuk RAC, et al. Prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2018;362:k3581. Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Fenton JJ, Weyrich MS, Durbin S, Liu Y, Bang H, Melnikow J. Prostate-specific antigen–based screening for prostate cancer. JAMA. 2018;319:1914.

Article PubMed Google Scholar * Paschen U, Sturtz S, Fleer D, Lampert U, Skoetz N, Dahm P. Assessment of prostate‐specific antigen screening: an evidence‐based report by the German

Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. BJU Int. 2022;129:280–9. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Ilic D, Djulbegovic M, Jung JH, Hwang EC, Zhou Q, Cleves A, et al. Prostate

cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;k3519. * Martin RM, Donovan JL, Turner EL, Metcalfe C, Young GJ, Walsh EI, et al.

Effect of a Low-Intensity PSA-Based Screening Intervention on Prostate Cancer Mortality. JAMA 2018;319:883. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Just J, Osgun F, Knight C.

Lower urinary tract symptoms and prostate cancer: is PSA testing in men with symptoms wise? Br J Gen Pract [Internet]. 2018;68:541–2. https://bjgp.org/content/68/676/541. Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Merriel SWD, Pocock L, Gilbert E, Creavin S, Walter FM, Spencer A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of prostate-specific antigen (PSA)

for the detection of prostate cancer in symptomatic patients. BMC Med. 2022;20:54. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * National Cancer Institute. Prostate-Specific

Antigen (PSA) Test. 2022. * NICE guildeline [NG12]. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. 2015. * Matti B, Xia W, van der Werf B, Zargar-Shoshtari K. Age-adjusted reference values for

prostate specific antigen – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2022;20:e114–25. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Crawford ED, Moul JW, Rove KO, Pettaway CA,

Lamerato LE, Hughes A. Prostate-specific antigen 1.5-4.0 ng/mL: a diagnostic challenge and danger zone. BJU Int [Internet]. 2011;108:1743–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21711431/.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Deantoni EP, Crawford ED, Oesterling JE, Ross CA, Berger ER, McLeod DG, et al. Age- and race-specific reference ranges for prostate-specific antigen

from a large community-based study. Urol [Internet]. 1996;48:234–9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8753735/. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Espaldon R, Kirby KA, Fung KZ, Hoffman

RM, Powell AA, Freedland SJ, et al. Probability of an abnormal screening prostate-specific antigen result based on age, race, and prostate-specific antigen threshold. Urology

2014;83:599–605. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rodgers M, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Roberts H, Britten N, et al. Testing Methodological Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative

Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. Evaluation. 2009;15:49–73. Article Google Scholar * Lacher DA, Hughes JP. Total, free, and complexed prostate-specific antigen levels among US men,

2007–2010. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;448:220–7. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rhodes T, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, st. Sauver JL, Sarma AV, Girman CJ, et al. Benign

prostate specific antigen distribution and associations with urological outcomes in community dwelling black and white men. J Urol. 2012;187:87–91. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Rhodes

T, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, st. Sauver JL, Sarma AV, Girman CJ, et al. Distribution and associations of [−2]proenzyme-prostate specific antigen in community dwelling black and white men. J

Urol. 2012;187:92–6. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Lacher D, Thompson T, Hughes J, Saraiya M. Total, free, and percent free prostate-specific antigen levels among U.S. men,

2001-04. Adv Data [Internet]. 2006;(379)(Dec):1–12. https://europepmc.org/article/MED/17348177. Google Scholar * Weinrich MC, Jacobsen SJ, Weinrich SP, Moul JW, Oesterling JE, Jacobson D,

et al. Reference ranges for serum prostate-specific antigen in black and white men without cancer. Urology 1998;52:967–73. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Saraiya M, Kottiri BJ,

Leadbetter S, Blackman D, Thompson T, McKenna MT, et al. Total and percent free prostate-specific antigen levels among U.S. Men, 2001-2002. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. Biomark

[Internet]. 2005;14:2178–82. https://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/14/9/2178. CAS Google Scholar * Sarma AV, St. Sauver JL, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Klee GG, Lieber MM, et al. Racial

differences in longitudinal changes in serum prostate-specific antigen levels: the olmsted county study and the flint men’s health study. Urology. 2014;83:88–93. Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Matti B, Zargar-Shoshtari K. Age-adjusted reference values for prostate-specific antigen in a multi-ethnic population. Int J Urol [Internet]. 2021;28:578–83.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33599031/. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Gray MA, Delahunt B, Fowles JR, Weinstein P, Cooke RR, Nacey JN. Assessment of ethnic variation in serum

levels of total, complexed and free prostate specific antigen. Comparison of Maori, Pacific Island and New Zealand European populations. Pathology 2003;35:480–3. Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Gray M, Borman B, Crampton P, Weinstein P, Wright C, Nacey J Elevated serum prostate-specific antigen levels and public health implications in three New Zealand ethnic groups:

European, Maori, and Pacific Island men - PubMed [Internet]. The New Zealand Medical Journal. 2005 [cited 2021 Sep 29]. p. U1295. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15711628/. *

Evans S, Metcalfe C, Patel B, Ibrahim F, Anson K, Chinegwundoh F, et al. Clinical presentation and initial management of Black men and White men with prostate cancer in the United Kingdom:

the PROCESS cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:249–54. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kheirandish P, Chinegwundoh F. Ethnic differences in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer.

2011;105:481–5. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Evans S, Metcalfe C, Ibrahim F, Persad R, Ben-Shlomo Y. Investigating Black-White differences in prostate cancer

prognosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:430–5. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among

race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35:407–11. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Metcalfe C, Patel B, Evans S, Ibrahim F,

Anson K, Chinegwundoh F, et al. The risk of prostate cancer amongst South Asian men in southern England: the PROCESS cohort study. BJU Int. 2008;0:080606123516618. Article Google Scholar

Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work was funded by Cancer Research UK [grant code: EDDCPJT\100031] and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care

Research Funding Round I-IV. TBM was supported by a Cancer Research UK Post-doctoral Fellowship (C56361/A26124). SERB was funded by a NIHR Advanced Fellowship (NIHR301666) whilst undertaking

this work. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. This research is linked to the CanTest

Collaborative, which is funded by Cancer Research UK [C8640/A23385], of which SWDM is a Clinical Senior Research Fellow. This work was supported by a generous donation from the Higgins

family. The donor had no input into the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, write up, or decision to submit this article for publication. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND

AFFILIATIONS * University of Exeter, St Luke’s Campus, Heavitree Road, Exeter, Devon, EX1 2LU, UK Melissa Barlow, Liz Down, Luke Timothy Allan Mounce, Samuel William David Merriel, Tanimola

Martins & Sarah Elizabeth Rose Bailey * University of Bristol, Bristol Medical School, Bristol, BS8 1TH, UK Jessica Watson Authors * Melissa Barlow View author publications You can also

search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Liz Down View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Luke Timothy Allan Mounce View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Samuel William David Merriel View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Jessica Watson View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tanimola Martins View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Sarah Elizabeth Rose Bailey View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS Conception and design: MB, LD, TM, SERB.

Clinical information: SWDM, JW. Data collection: all authors, led by MB and LD. Data analysis: MB, LD, LTAM. Data interpretation: all authors. Manuscript writing, editing, and final

approval: all authors. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Melissa Barlow. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION FULL SEARCH TERMS ADAPTATION

OF THE NEWCASTLE-OTTAWA QUALITY ASSESSMENT SCALE RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS OPEN ACCESS This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits

use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the

Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated

otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds

the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Reprints and

permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Barlow, M., Down, L., Mounce, L.T.A. _et al._ Ethnic differences in prostate-specific antigen levels in men without prostate cancer: a

systematic review. _Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis_ 26, 249–256 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-022-00613-7 Download citation * Received: 09 August 2022 * Revised: 18 October 2022 *

Accepted: 31 October 2022 * Published: 01 December 2022 * Issue Date: June 2023 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-022-00613-7 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with

will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt

content-sharing initiative