- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT BACKGROUND The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically altered the psychosocial environment of pregnant women and new mothers. In addition, prenatal infection is a known risk factor for

altered fetal development. Here we examine joint effects of maternal psychosocial stress and COVID-19 infection during pregnancy on infant attention at 6 months postpartum. METHOD

One-hundred and sixty-seven pregnant mothers and infants (40% non-White; _n_ = 71 females) were recruited in New York City (_n_ = 50 COVID+, _n_ = 117 COVID–). Infants’ attentional

processing was assessed at 6 months, and socioemotional function and neurodevelopmental risk were evaluated at 12 months. RESULTS Maternal psychosocial stress and COVID-19 infection during

pregnancy jointly predicted infant attention at 6 months. In mothers reporting positive COVID-19 infection, higher prenatal psychosocial stress was associated with lower infant attention at

6 months. Exploratory analyses indicated that infant attention in turn predicted socioemotional function and neurodevelopmental risk at 12 months. CONCLUSIONS These data suggest that

maternal psychosocial stress and COVID-19 infection during pregnancy may have joint effects on infant attention at 6 months. This work adds to a growing literature on the effects of the

COVID-19 pandemic on infant development, and may point to maternal psychosocial stress as an important target for intervention. IMPACT * This study found that elevated maternal psychosocial

stress and COVID-19 infection during pregnancy jointly predicted lower infant attention scores at 6 months, which is a known marker of risk for neurodevelopmental disorder. In turn, infant

attention predicted socioemotional function and risk for neurodevelopmental disorder at 12 months. These data suggest that maternal psychosocial stress may modulate the effects of

gestational infection on neurodevelopment and highlight malleable targets for intervention. You have full access to this article via your institution. Download PDF SIMILAR CONTENT BEING

VIEWED BY OTHERS PANDEMIC BEYOND THE VIRUS: MATERNAL COVID-RELATED POSTNATAL STRESS IS ASSOCIATED WITH INFANT TEMPERAMENT Article 20 April 2022 PRENATAL MENTAL HEALTH AND EMOTIONAL

EXPERIENCES DURING THE PANDEMIC: ASSOCIATIONS WITH INFANT NEURODEVELOPMENT SCREENING RESULTS Article 02 March 2024 MATERNAL PERCEIVED STRESS AND INFANT BEHAVIOR DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Article Open access 27 July 2023 INTRODUCTION Psychosocial stress during pregnancy is a known risk factor for altered neurodevelopment and risk for psychiatric disorders in later life.1 In

addition, psychosocial stress is also related to higher susceptibility to contracting infections and generally lower quality of physical health.2,3,4 Examining the effects of maternal

prenatal psychosocial stress and infection on infant outcomes is particularly timely in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the current study, we evaluate the joint influences of

maternal prenatal psychosocial stress and COVID-19 infection during pregnancy on objective measures of infant outcomes in a prospective longitudinal study of 167 mother–infant dyads.

Specifically, we examine the effects on infant attention at 6 months postpartum, given that early attention is a reliable predictor of cognitive and socioemotional development and long-term

neurodevelopmental outcomes.5,6,7 ATTENTION AS A WINDOW INTO UNDERSTANDING THE EFFECTS OF PRENATAL STRESS ON NEURODEVELOPMENT There is a large literature linking prenatal stress to

neurodevelopmental outcomes. Multiple meta-analyses have demonstrated robust associations between maternal mental health during pregnancy and delays across infant cognitive and

socioemotional outcomes.8,9 Of relevance to the COVID-19 pandemic, a recent meta-analysis found that stress connected specifically to the occurrence of natural disasters during pregnancy was

associated with adverse outcomes across nearly all domains of child development, including cognitive, motor, socioemotional, and behavioral development.10 Despite this evidence, previous

studies examining maternal prenatal stress have largely relied on global measures of cognitive ability (e.g., the Bayley Scales of Infant Development) or on maternal report measures of

infant development (e.g., the Ages and Stages Questionnaire) rather than objective assessments of specific cognitive domains. While general measures of infant development may be useful for

identifying infants at risk for severe developmental delays, there are several limitations to using these global measures, including potential confounds arising from parental or examiner’s

subjective ratings as well as poor correlations with long-term cognitive outcomes.11,12 Behavioral assessments of infant attention, measured through direct, standardized observations of

infant looking behavior, may provide a reliable window into the early brain and cognitive development.13,14,15 Visual attention is a foundational cognitive capacity that is observable from

early infancy and shows rapid developmental change, particularly over the first postnatal year.15,16 Importantly, animal models have also linked specific aspects of visual attention to key

brain networks.17,18 Beyond serving as a behavioral correlate of brain function, visual attention also predicts cognitive and socioemotional outcomes in later infancy and childhood. Even

relatively coarse objective measures of infant attention, such as looking durations, have been shown to predict higher-order cognition in later childhood.19,20,21,22 Atypical patterns of

attentional development are also one of the earliest behavioral markers of risk for numerous neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism,5 attention-deficit disorder,23 and anxiety

disorders.24 As such, examining individual differences in infant attention may be valuable for predicting subsequent developmental outcomes. Moreover, this capacity is also externally

observable from early in postnatal life through measurement of infant looking behavior, allowing for objective assessment of individual differences from early in infancy. The anatomical

connections supporting attentional control and behavioral regulation are established in utero.25 These cortical connections are thus vulnerable to shaping by environmental signals even

before birth.1 Increasing evidence shows associations between prenatal stress and phenotypic alterations in infant attentional processing using both maternal report measures26,27 and

measurement of infant looking behavior.28,29 Recent findings point to inflammatory processes as one mechanistic pathway through which maternal prenatal stress may impact fetal development.

For instance, elevated psychosocial stress, whether chronic or in response to stressful life events, is linked to elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can cross the placenta

during pregnancy and adversely influence fetal outcomes.30 Moreover, multiple exposures that elevate inflammatory levels during pregnancy, such as from repeated immune activation or chronic

stress exposure, may have compounding impacts on neurocognitive development in offspring.31 POSSIBLE SEQUALAE OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC ON INFANT DEVELOPMENTAL OUTCOMES The COVID-19 pandemic

has drawn heightened attention to possible interactions between infection and neuropsychological function. Even relatively minor cases of COVID-19 infection have been shown to predict

elevated risk of new-onset mental health problems in the general population,32,33,34 and can even lead to more severe psychiatric sequelae.35 These neurological and psychiatric effects may

be related to the peripheral immune response to infection.36,37 Indeed, COVID-19 infection is associated with elevated inflammatory markers and increased cytokine expression,38 which can

contribute to neurological dysfunction.39 Thus, it is possible that the peripheral immune response to COVID-19 infection may have downstream impacts on infant neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Knowledge of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on infant development is relatively limited. There is some evidence that maternal COVID-19 pandemic-related stress is associated with altered

infant temperament, including decreased surgency in 3-month-olds40 and decreased regulatory capacity at 4 and 6 months of age.41 However, other research has found that maternal depressive

symptoms measured during the COVID-19 pandemic were not associated with infant temperament,42 and that exposure to the pandemic in general had no association with infant socioemotional or

language outcomes.43 In regards to direct effects of maternal prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure, existing reports, to date, have found no significant associations between maternal prenatal

infection and infant outcomes, measured through maternal report at 6 months of age.44 However, there are likely important individual differences that may modulate individual risk. In

particular, the COVID-19 pandemic presented a vast number of psychosocial stressors, even in individuals not directly infected with the virus. Indeed, data from large samples of perinatal

individuals across the United States has shown that these psychosocial aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic adversely influenced perinatal mental health and stress levels.45,46 It is possible

that these psychosocial sequalae may modulate individual risk from infection or exert independent effects on early neurodevelopment. However, there is scant evidence examining interactions

between prenatal COVID-19 infection and psychosocial stress in predicting infant developmental outcomes. THE CURRENT STUDY Here we examine whether maternal prenatal psychosocial stress and

COVID-19 infection are associated with early infant neurodevelopmental outcomes, using infant attention as a behavioral model. In addition, we also conduct exploratory analyses examining

longitudinal associations with socioemotional outcomes and neurodevelopmental risk at 12 months. Understanding individual differences that may influence infant outcomes is key for

identifying mothers and infants at increased risk, and may have direct impacts on targeting personalized therapies to support adaptive long-term outcomes. METHOD PARTICIPANTS The current

sample included 167 mothers and their infants (_n_ = 71 females, _n_ = 96 males) enrolled between March 2020 and January 2023. The racial breakdown of infants in the full sample was as

follows: 60% White, 17% two or more races, 8% other, 5% Asian, 5% Black, and 5% not reported. In addition, 24% of the sample identified as Hispanic or Latino. Mothers were recruited from NYU

Langone Health medical records as part of an ongoing, prospective longitudinal study (_n_ = 117 COVID-negative, _n_ = 50 COVID-positive). Prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure was defined based on

maternal report of positive COVID-19 infection during pregnancy. This was probed using the COPE: COVID-19 & Perinatal Experiences – Impact Survey47 and the Novel Coronavirus Illness

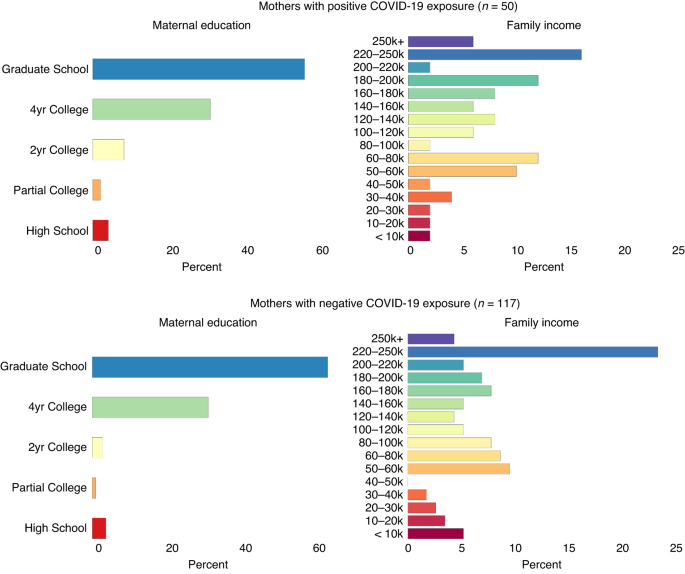

Patient Report Survey.33 We verified that there were no differences in sociodemographic characteristics between mothers with positive prenatal COVID-19 exposure and those who were not

exposed, _p_s > 0.16. Additional sociodemographic information by COVID-19 exposure group is reported in Fig. 1. PROTOCOL Maternal self-reported psychosocial stress and COVID-19 exposure

were evaluated during a baseline assessment. When infants were 6 months of age (_M_ age = 6.64 months, SD = 0.70 months), families then participated in a remote free-viewing visual attention

assessment in the home. The remote visual attention task occurred synchronously through Zoom using laptops (71%) or smartphones (29%). A short (80-s) Sesame Street video (Cecile - Up Down,

In Out, Over and Under) used in previous in-lab assessments of infant attention48 was adapted for mobile testing through Zoom.49 In brief, parents were asked to participate in a quiet area

of their home relatively free from distractions and were instructed to hide both their own and the experimenter’s video. Experimenters guided parents through positioning their infants so

that infants’ eye movements to animated cartoons presented on the left, right, bottom, and top of the screen could be clearly seen during a calibration procedure prior to testing.

Experimenters recorded the infants for subsequent post hoc analysis of infants’ gaze behavior using an online webcam-linked eye tracker (OWLET) developed to analyze infant eye-tracking data

collected on personal devices in the home.50 In addition, caregivers used an 18-inch tape measure that was mailed to families prior to participation to measure their distance from the screen

during the visual attention task. Caregivers also reported the specific testing device used during the study, which was used to obtain the dimensions of the testing screen. This information

was used to estimate the visual angle of viewing. We verified that individual differences in visual angle were not correlated with the total looking time or attention-orienting variables,

_r_s < 0.12, _p_s > 0.22. Families were invited to participate in a follow-up assessment when infants were approximately 12 months of age. Ninety-nine mothers (60%) completed surveys

on infant socioemotional development and neurodevelopmental risk during this follow-up assessment (_M_ age = 12.32 months, SD = 0.53 months; _n_ = 37 females, _n_ = 62 males; _n_ = 71

COVID-negative, _n_ = 28, COVID-positive). Attrition from 6 to 12 months occurred due to study dropout (_n_ = 36) or due to not completing the survey on infant socioemotional outcomes (_n_ =

32). To test for potential attrition-related biases, we ran multiple t-tests to assess for differences in maternal prenatal psychosocial stress levels, COVID-19 exposure, postnatal

depression, or family sociodemographic characteristics between 6 and 12 months. Results indicated no differences between families who provided data at both timepoints and those who did not,

_p_s > 0.14. MATERNAL MEASURES MATERNAL PRENATAL PSYCHOSOCIAL STRESS Maternal psychosocial distress was measured in pregnant mothers using maternal report of depressive symptoms, anxiety,

physical complaints, and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and somatic issues were evaluated using the Depression, Anxiety, and Somatic subscales of the Brief

Symptom Inventory (BSI-18).51 In addition, symptoms of post-traumatic stress were assessed using a modified version of the PCL-5 PTSD Checklist for DSM-5.52 Both the BSI-18 and PCL-5 ask

subjects to indicate the distress they have experienced from each symptom in the past two weeks on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all; 5 = extremely). The suicidality item from the

BSI-18 was omitted. In total, there were five items probing depressive symptoms, six probing anxiety symptoms, six probing somatic symptoms, and ten probing post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Scores from each subscale were averaged to generate a total psychosocial stress score. Reliability was high for the overall psychosocial stress measure (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93, 95% CI =

[0.92, 0.94]). SIX-MONTH ATTENTION MEASURES LOOKING TIME AND ORIENTING PATTERNS Infant total looking time and visual orienting patterns were assessed while infants watched an 80-s Sesame

Street video during a remote free-viewing visual attention assessment (see protocol for full administration details). Total looking time was calculated by summing the time that infants’

point-of-gaze fell within the screen boundaries during the 80-s video. Infant total looking time was used as a proxy of focused attention and information processing efficiency, consistent

with standard approaches.20,53,54 Infant attention-orienting patterns were evaluated during segments of the Sesame Street video in which multiple salient regions were present (occurring at

approximately 33–37 s, 45–51 s, 56–62 s, and 67–71 s), eliciting competition for attentional resources. Saliency maps were computed for each frame in these segments (at 30 frames per second)

using a static saliency model implemented using the OpenCV library in Python.55 In contrast to more computationally intensive models, the static saliency model does not rely on the linear

summation of individual feature maps for color, intensity, motion, or depth.56 Instead, this algorithm computes saliency maps by evaluating regions of an image that “pop out” from the

background by analyzing the log spectrum of an image (see Supplemental Information for heatmaps of the computed saliency maps across the four video segments). Prior work shows that this

algorithm approximates human determinations of salient regions and performs equivalently or better than more computationally intensive methods that rely on the linear summation of feature

maps.55 Infant attention-orienting scores were then computed by analyzing cross-correlations between the coordinates of infants’ point-of-gaze and the coordinates with the maximum saliency

value on a frame-by-frame basis across these four segments. Higher scores indicate that infants are primarily oriented toward the most visually salient regions across video frames rather

than orienting attention amongst multiple competing areas of interest. As such, we use infants’ orienting scores as an exploratory index of attentional flexibility. REGULATORY CAPACITY

Parental report data on infant attentional control and regulatory function was collected using the revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire – very short form (IBQ-VSF).57 We use the Regulatory

Capacity factor of the IBQ-VSF in the current analysis, which provides a global parent-report measure of infant attentional and regulatory functioning in their everyday environments. This

measure captures additional aspects of infant attentional control that may not emerge during a short testing session, and has shown high relation with laboratory measures of attention.58

Indeed, prior research has found that infant looking behavior is associated with parent-report measures of infant regulatory capacity, with shorter looking times generally predicting higher

regulation.59,60,61 TWELVE-MONTH SOCIOEMOTIONAL MEASURES Socioemotional outcomes and neurodevelopmental risk were assessed using the Brief Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment

(BITSEA). The BITSEA is a parent-report screening tool designed to identify children with possible deficits or delays in socioemotional and behavioral development. This measure contains 42

questions, each requiring one of three responses (true/rarely, somewhat true/sometimes, or very true/often), and has been validated in infants and toddlers ages 12–36 months.62 Although this

measure is not diagnostic, prior research has found that it has high predictive validity in identifying children at risk for socioemotional delays and neurodevelopmental disorders.63 The

BITSEA yields a Competence Total Score, which indexes normative socioemotional development, a Problem Total Score, which indexes possible socioemotional developmental delays. In addition,

the BITSEA also yields an Autism-Competence Risk Score, an Autism-Problem Score, and an Autism Total Risk Score, which is equal to the Autism-Problem Score minus the Autism-Competence Score.

Here we use the Autism Total Risk Score as an index of overall neurodevelopmental risk. COVARIATES PRIOR MATERNAL MOOD/ANXIETY DISORDER Mothers were asked to report on a binary measure of

whether they had previously been diagnosed with a mood or anxiety disorder (yes or no). MATERNAL POSTPARTUM DEPRESSION At 6 months postpartum, maternal postpartum depression was assessed

using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).64 The EPDS consists of 10 items probing the severity of postpartum depression and anxiety symptoms, which are rated on a four-point

Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very often). Scores were summed across all items. SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS Prior work has indicated associations between socioeconomic status (SES)

and infant attention.6,65 Thus, we used categorical scales of family income as a proxy for SES (Fig. 1). ANALYTICAL PLAN Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to derive a global

measure of infant attention. We modeled infant attention as a latent variable to provide a more comprehensive assessment of attention than any one observed variable by itself could provide.

In addition, unlike statistical analyses that focus solely on observed variables, CFA explicitly models measurement error such that observed variables are represented by both the true score

and measurement error. Multiple linear regressions were then used to evaluate whether interactions between prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure and psychosocial stress predicted individual

differences in infant attention. In addition, we also examined exploratory longitudinal associations between infant attention and subsequent socioemotional outcomes and neurodevelopmental

risk at 12 months. Missing data were accounted for using full-information maximum likelihood estimation, which generates unbiased estimates for data missing at random and is superior to

other methods for handling missing data, including listwise deletion, pairwise deletion, or mean imputation.66 Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test indicated that the data fit

an MCAR pattern, _χ_2 = 107.87, _p_ = 0.16. Analyses were conducted using MPlus v.8. RESULTS Descriptive statistics for primary study variables are displayed in Table 1, and correlations

among all variables are displayed in Table 2. PREDICTORS OF PRENATAL PSYCHOSOCIAL STRESS IN MOTHERS EXPOSED TO THE SARS-COV-2 VIRUS Prior to testing primary hypotheses, we first explored

interactions between maternal SARS-CoV-2 exposure and relevant sociodemographic variables (income, prior history of mood or anxiety disorder) in predicting maternal prenatal psychosocial

stress. In mothers reporting positive SARS-CoV-2 exposure, neither mood/anxiety disorder history, _β_ = 0.09, _p_ = 0.56, nor family income, _β_ = 0.10, _p_ = 0.53, were predictive of

psychosocial stress levels (Fig. 2). In contrast, both mood/anxiety disorder history, _β_ = 0.33, _p_ < 0.01, and lower family income, _β_ = −0.34, _p_ < 0.01, were significant

predictors of psychosocial stress in mothers reporting no SARS-CoV-2 exposure during pregnancy (Fig. 2). These findings provide behavioral evidence in support of the hypothesis that elevated

psychosocial stress in individuals experiencing COVID-19 infection may be tied to peripheral effects of infection.32,35 EFFECTS OF MATERNAL PSYCHOSOCIAL STRESS AND SARS-COV-2 EXPOSURE ON

INFANT ATTENTION Next, the effects of maternal prenatal psychosocial stress and SARS-CoV-2 exposure on infant attention were evaluated. A latent measure of infant attention was derived using

CFA with the observed attention variables (look duration, attention-orienting score, and regulatory capacity) as indicators. A unidimensional model fit the data, CFI = 1.00, _χ_2 = 14.29,

_p_ = 0.002, RMSEA = 0, SRMR = 0, with all factor loadings in the expected direction (look duration: _β_ = –0.32, 95% CI [0.06, 0.45], _p_ = 0.02; attention orienting: _β_ = –0.43, 95% CI

[0.12, 0.91], _p_ = 0.01; regulatory capacity: _β_ = 0.68, 95% CI [0.22, 1.61], _p_ = 0.01). The latent measure of infant attention was regressed onto maternal prenatal psychosocial stress,

prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure, and the interaction between these variables. Family income, history of a mood/anxiety disorder, and infant age were included as covariates. Results indicated a

main effect of prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure, _β_ = 0.60, 95% CI [0.46, 0.75], _p_ < 0.01, but no significant main effect of maternal prenatal psychosocial stress, _β_ = –0.09, 95% CI

[–0.27, 0.09], _p_ = 0.42. Importantly, however, there was an interaction between prenatal psychosocial stress and SARS-CoV-2 exposure on infant attention, _β_ = –0.68, 95% CI [–0.64,

–0.10], _p_ < 0.01, such that higher psychosocial stress during pregnancy was associated with poorer attention scores in infants of mothers reporting positive prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure

but not in mothers reporting negative prenatal SARS-CoV-2 exposure (Fig. 3). We evaluated the robustness of these effects when controlling for maternal depression at 6 months postpartum.

The interaction between maternal prenatal psychosocial stress and SARS-CoV-2 exposure on infant attention remained robust, _β_ = –0.67, 95% CI [–0.82, –0.52], _p_ < 0.01. In addition,

infant attention was not predicted by current postpartum depression scores, _β_ = –0.09, 95% CI [–0.26, 0.09], _p_ = 0.43. LONGITUDINAL ASSOCIATIONS WITH INFANT SOCIOEMOTIONAL OUTCOMES AT 12

MONTHS Finally, we conducted exploratory analyses examining associations between infant attention scores and socioemotional outcomes and neurodevelopmental risk at 12 months of age. Raw

total scores for the socioemotional competence, socioemotional problems, and autism risk subscales of the BITSEA were used as dependent variables. Family income, maternal mood/anxiety

disorder history, and infant age were included as control variables. There were no interactions between maternal prenatal psychosocial stress and SARS-CoV-2 exposure on infant socioemotional

outcomes at 12 months, _p_s > 0.19, _β_s < 0.17. However, higher latent infant attention scores at 6 months were associated with higher socioemotional competence, _β_ = 0.27, 95% CI

[0.06, 0.49], _p_ = 0.02, and lower neurodevelopmental risk, _β_ = –0.32, 95% CI [–0.53, –0.11], _p_ < 0.01 (Fig. 3). There were no significant effects of infant attention on

socioemotional problems at 12 months, _β_ = –0.10, 95% CI [–0.33, 0.13], _p_ = 0.39 (Fig. 4). DISCUSSION Here we evaluated the impacts of the global COVID-19 pandemic on early

neurodevelopment using infant attention as a behavioral model. We examined the psychosocial effects of the pandemic through impacts on maternal prenatal psychosocial stress, as well as the

effects of maternal gestational exposure to the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) on infant attention and socioemotional development. Our results suggest that maternal self-reported

psychosocial stress and SARS-CoV-2 exposure during pregnancy jointly impacted infant attention development at 6 months. In particular, mothers with higher psychosocial stress who were also

infected with the COVID-19 virus during the pandemic were more likely to have infants with lower scores on a global latent measure of attention characterized by longer looking times, lower

regulatory capacity, and different patterns of attentional orienting during a free-viewing attention assessment. These global patterns of attention, assessed through standardized laboratory

assessments, are thought to reflect less efficient information processing and attentional control.54 We also conducted exploratory analyses examining longitudinal associations between infant

attention and subsequent socioemotional development and neurodevelopmental risk at 12 months. Our results indicated that there were no direct effects of prenatal psychosocial stress or

maternal SARS-CoV-2 exposure on infant socioemotional competence. However, we found that higher attention scores at 6 months were correlated with higher socioemotional competence and lower

neurodevelopmental risk scores at 12 months of age, regardless of maternal prenatal infection or psychosocial stress exposure. The different patterns of infant attention, at different ages,

observed in the current study may indicate alterations in child neurodevelopmental trajectories. However, it is also possible that observed attention patterns may reflect differences in the

conditioning of autonomic responses that facilitate mother–infant attachment, beginning in utero. For instance, calming cycle theory posits that normal gestation and birth results in

autonomic co-regulation between the mother and infant, producing physiological and behavioral effects that ensure mutual attraction between the dyad67. Disruptions to this autonomic

co-regulation, such as due to physiological sequalae of prenatal stress and infection, may result in different patterns of infant attention and orienting behaviors. Regardless of the

underlying mechanisms driving differences in infant attention, these phenotypic alterations could be adaptive across many contexts. For instance, if paired with appropriate caregiver

scaffolding, increased attentional orienting to salient stimuli, as captured by the attentional orienting component of our global latent construct of attention, might promote better learning

from environmental cues.68,69 However, these changes may also convey an increased risk for neuropsychiatric or neurodevelopment disorders in some contexts.70 For instance, prior work has

shown that infants subsequently diagnosed with neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism and ADHD, demonstrate early differences in attentional processing.5,23,71,72,73 These findings

broadly align with the observed longitudinal associations between infant attention and neurodevelopmental risk in our sample. However, it is important to note that our socioemotional

measures relied solely on maternal report, evaluated using the BITSEA questionnaire.62 While this measure has been found to correlate with objective assessments of socioemotional problems

and has predictive validity for neurodevelopmental risk,63,74 it is not validated to diagnose disorders or delays. We also evaluated socioemotional development and neurodevelopmental risk at

an early timepoint during which substantial variability in developmental trajectories is observed. Given this, these individual differences are likely indicative of normative variability in

developmental trajectories. As well, attention is highly malleable to early postnatal experience,75,76 which could additionally buffer or elevate long-term neurodevelopmental risk. Further

investigations into both prenatal and postnatal modulators of early attention development, and possible cascading associations with neurodevelopmental outcomes, are needed to shed light on

these questions. Our findings should be interpreted within the limitations of our data. For one, while objective, standardized assessments of attention may be more ecologically valid in the

home, it also limits experimenter control over distractions and noise. Proximal aspects of the home environment (e.g., residential crowding, chaoticness, presence of other family members or

pets) could contribute to individual differences in infant attentional processing in the moment. Moreover, it is possible that using animated videos to measure infant looking time may

increase “attentional inertia”, such that some infants demonstrate longer looking times to television-based programming regardless of attentional capacity.77 This potential source of noise

in video-based measures of looking time highlights an additional benefit of using multiple indicators of attention in a structural equation modeling framework that accounts for measurement

error. Moreover, while assessing attention using standardized tasks facilitates comparisons with existing literature, alternative operationalizations of infant attention that are grounded in

the context of the dyadic mother–infant relationship may be more relevant for understanding infant neurodevelopment. For example, recent work proposes that measuring infant orienting

responses to socioemotional stimuli78 or mutual gaze between the mother and infant79 may be relevant behavioral outputs of infants’ physiological attention and approach systems. We also

relied on maternal report when defining COVID-19 exposure groups and did not have medical records of illness severity. Future work using direct biological markers of maternal infection is

needed to confirm these findings and probe the biological factors that may contribute to these effects. In addition, future studies should consider the biological and experiential factors

that may buffer maternal psychosocial stress, particularly in the context of stressful life events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, prior work indicates that anti-inflammatory

hormones such as oxytocin, which is involved in regulating childbirth and social bonding80, 81, could buffer against adverse downstream impacts of stress or prenatal infection on infant

outcomes. Finally, it is important to note that our findings are drawn from infants predominately from families with higher socioeconomic backgrounds in a single geographic region. Future

empirical and epidemiological studies are needed to replicate these findings and evaluate long-term outcomes, particularly amongst more socio-demographically diverse samples of families. In

sum, here we find evidence for interactions between prenatal psychosocial stress and maternal COVID-19 infection in predicting individual differences in infant attention, with potential

consequences for subsequent socioemotional development. A strength of our study is the use of multiple indices of infant attention that may otherwise be obscured when using single coarse

measures of attentional processing, such as measures based solely on caregiver report. In addition, our approach draws both on the ecological validity of caregiver observations across a

variety of environments combined with experimental measures of attention that provide a quantitative snapshot of variation in infant response to controlled stimuli. Taken together, these

findings may suggest that there are phenotypic adaptations in attention development in infants of mothers most significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and highlight the importance

of considering individual differences in modulating neurodevelopmental trajectories. DATA AVAILABILITY The data analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon

reasonable request. REFERENCES * Glover, V. Annual research review: prenatal stress and the origins of psychopathology: an evolutionary perspective. _J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry_ 52,

356–367 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Morey, J. N., Boggero, I. A., Scott, A. B. & Segerstrom, S. C. Current directions in stress and human immune function. _Curr. Opin.

Psychol._ 5, 13–17 (2015). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gouin, J.-P. & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. The impact of psychological stress on wound healing: methods and

mechanisms. _Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am._ 31, 81–93 (2011). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Kristenson, M., Eriksen, H. R., Sluiter, J. K., Starke, D. & Ursin, H.

Psychobiological mechanisms of socioeconomic differences in health. _Soc. Sci. Med._ 58, 1511–1522 (2004). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Johnson, M. H., Gliga, T., Jones, E. &

Charman, T. Annual research review: infant development, autism, and ADHD – early pathways to emerging disorders. _J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry_ 56, 228–247 (2015). Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Brandes-Aitken, A., Braren, S., Swingler, M., Voegtline, K. & Blair, C. Sustained attention in infancy: a foundation for the development of multiple aspects of self-regulation

for children in poverty. _J. Exp. Child Psychol._ 184, 192–209 (2019). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hendry, A., Johnson, M. H. & Holmboe, K. Early development of

visual attention: change, stability, and longitudinal associations. _Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol._ 1, 251–275 (2019). Article Google Scholar * Madigan, S. et al. A meta-analysis of maternal

prenatal depression and anxiety on child socioemotional development. _J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry_ 57, 645–657.e8 (2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Manzari, N.,

Matvienko-Sikar, K., Baldoni, F., O’Keeffe, G. W. & Khashan, A. S. Prenatal maternal stress and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in the offspring: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. _Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol._ 54, 1299–1309 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Lafortune, S. et al. Effect of natural disaster-related prenatal maternal

stress on child development and health: a meta-analytic review. _Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health_ 18, 8332 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Anderson, P. J.

& Burnett, A. Assessing developmental delay in early childhood—concerns with the Bayley-III scales. _Clin. Neuropsychol._ 31, 371–381 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar *

Muthusamy, S., Wagh, D., Tan, J., Bulsara, M. & Rao, S. Utility of the ages and stages questionnaire to identify developmental delay in children aged 12 to 60 months. _JAMA Pediatr._

176, 980 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Amso, D. & Scerif, G. The attentive brain: insights from developmental cognitive neuroscience. _Nat. Rev. Neurosci._

16, 606–619 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Oakes, L. M. & Amso, D. Development of visual attention. in _Stevens’ Handbook of Experimental Psychology and

Cognitive Neuroscience_ (ed. Wixted, J. T.) 1–33 (John Wiley & Sons). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119170174.epcn401 (2018). * Posner, M. I., Rothbart, M. K., Sheese, B. E. & Voelker,

P. Developing attention: behavioral and brain mechanisms. _Adv. Neurosci._ 2014, 1–9 (2014). Article Google Scholar * Rueda, M. R. & Posner, M. I. Development of attention networks.

in _The Oxford Handbook of Developmental Psychology_, Vol. 1 (ed. Zelazo, P. D.) 682–705 (Oxford University Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199958450.013.0024 (2013). *

Ungerleider, L. ‘What’ and ‘where’ in the human brain. _Curr. Opin. Neurobiol._ 4, 157–165 (1994). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * van Essen, D. C. & Maunsell, J. H. R.

Hierarchical organization and functional streams in the visual cortex. _Trends Neurosci._ 6, 370–375 (1983). Article Google Scholar * Rose, S. A., Feldman, J. F. & Jankowski, J. J.

Implications of infant cognition for executive functions at age 11. _Psychol. Sci._ 23, 1345–1355 (2012). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Cuevas, K. & Bell, M. A. Infant attention and

early childhood executive function. _Child Dev._ 85, 397–404 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Johnson, M. H., Posner, M. I. & Rothbart, M. K. Components of visual orienting in

early infancy: contingency learning, anticipatory looking, and disengaging. _J. Cogn. Neurosci._ 3, 335–344 (1991). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Papageorgiou, K. A. et al.

Individual differences in infant fixation duration relate to attention and behavioral control in childhood. _Psychol. Sci._ 25, 1371–1379 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Miller,

M., Iosif, A.-M., Young, G. S., Hill, M. M. & Ozonoff, S. Early detection of ADHD: insights from infant siblings of children with autism. _J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol._ 47, 737–744

(2018). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Pérez-Edgar, K. Attention mechanisms in behavioral inhibition: exploring and exploiting the environment. in _Behavioral Inhibition_ 237–261

(Springer International Publishing). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-98077-5_11 (2018). * Tau, G. Z. & Peterson, B. S. Normal development of brain circuits. _Neuropsychopharmacology_

35, 147–168 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Plamondon, A. et al. Spatial working memory and attention skills are predicted by maternal stress during pregnancy. _Early Hum. Dev._

91, 23–29 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Ronald, A., Pennell, C. E. & Whitehouse, A. J. O. Prenatal maternal stress associated with ADHD and autistic traits in early

childhood. _Front. Psychol._ 1, 223 (2011). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Merced‐Nieves, F. M., Dzwilewski, K. L. C., Aguiar, A., Lin, J. & Schantz, S. L.

Associations of prenatal maternal stress with measures of cognition in 7.5‐month‐old infants. _Dev. Psychobiol._ 63, 960–972 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Tu, H.-F., Skalkidou,

A., Lindskog, M. & Gredebäck, G. Maternal childhood trauma and perinatal distress are related to infants’ focused attention from 6 to 18 months. _Sci. Rep._ 11, 24190 (2021). Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Beijers, R., Buitelaar, J. K. & de Weerth, C. Mechanisms underlying the effects of prenatal psychosocial stress on child outcomes: beyond

the HPA axis. _Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry_ 23, 943–956 (2014). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hantsoo, L., Kornfield, S., Anguera, M. C. & Epperson, C. N. Inflammation: a

proposed intermediary between maternal stress and offspring neuropsychiatric risk. _Biol. Psychiatry_ 85, 97–106 (2019). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mazza, M. G. et al. Anxiety and

depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. _Brain Behav. Immun._ 89, 594–600 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Thomason, M.

E., Werchan, D. & Hendrix, C. L. COVID-19 patient accounts of illness severity, treatments and lasting symptoms. _Sci. Data_ 9, 2 (2022). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google

Scholar * Thomason, M. E., Hendrix, C. L., Werchan, D. & Brito, N. H. Perceived discrimination as a modifier of health, disease, and medicine: empirical data from the COVID-19 pandemic.

_Transl. Psychiatry_ 12, 284 (2022). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Taquet, M., Luciano, S., Geddes, J. R. & Harrison, P. J. Bidirectional associations between

COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. _Lancet Psychiatry_ 8, 130–140 (2021). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Boldrini, M.,

Canoll, P. D. & Klein, R. S. How COVID-19 affects the brain. _JAMA Psychiatry_ 78, 682 (2021). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Iadecola, C., Anrather, J. & Kamel,

H. Effects of COVID-19 on the nervous system. _Cell_ 183, 16–27.e1 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Mukerji, S. S. & Solomon, I. H. What can we learn from

brain autopsies in COVID-19? _Neurosci. Lett._ 742, 135528 (2021). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Beurel, E., Toups, M. & Nemeroff, C. B. The bidirectional relationship of

depression and inflammation: double trouble. _Neuron_ 107, 234–256 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Provenzi, L. et al. Prenatal maternal stress during the

COVID-19 pandemic and infant regulatory capacity at 3 months: a longitudinal study. _Dev. Psychopathol._ 35, 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579421000766 (2023). * Bianco, C. et al.

Pandemic beyond the virus: maternal COVID-related postnatal stress is associated with infant temperament. _Pediatr. Res._ 93, 253–259 (2023). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fiske,

A., Scerif, G. & Holmboe, K. Maternal depressive symptoms and early childhood temperament before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic in the United Kingdom. _Infant Child Dev._ 31, e2354

(2022). * Sperber, J. F., Hart, E. R., Troller‐Renfree, S. V., Watts, T. W. & Noble, K. G. The effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on infant development and maternal mental health in the

first 2 years of life. _Infancy_ 28, 107–135 (2023). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Shuffrey, L. C. et al. Association of birth during the COVID-19 pandemic with neurodevelopmental

status at 6 months in infants with and without in utero exposure to maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection. _JAMA Pediatr._ 176, e215563 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar *

Werchan, D. M. et al. Behavioral coping phenotypes and associated psychosocial outcomes of pregnant and postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic. _Sci. Rep._ 12, 1209 (2022). Article

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Hendrix, C. L. et al. Geotemporal analysis of perinatal care changes and maternal mental health: an example from the COVID-19 pandemic. _Arch.

Womens Ment. Health_ 25, 943–956 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Thomason, M. E., Graham, A. & VanTieghem, M. R. _The COPE-IS: Coronavirus Perinatal

Experiences–Impact Survey_ (2020). COVGEN. https://www.covgen.org/cope-surveys * Kraybill, J. H., Kim-Spoon, J. & Bell, M. A. Infant attention and age 3 executive function. _Yale J. Bio.

Med._ 92, 3–11 (2019). Google Scholar * Gustafsson, H. C. et al. Innovative methods for remote assessment of neurobehavioral development. _Dev. Cogn. Neurosci._ 52, 101015 (2021). Article

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Werchan, D. M., Thomason, M. E. & Brito, N. H. OWLET: an automated, open-source method for infant gaze tracking using smartphone and webcam

recordings. _Behav. Res. Methods_ 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01962-w (2022). * Derogatis, L. R. _BSI 18, Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration, Scoring and Procedures

Manual_ (NCS Pearson, Incorporated., 2001). * Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K. & Domino, J. L. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for _DSM-5_ (PCL-5):

development and initial psychometric evaluation. _J. Trauma Stress_ 28, 489–498 (2015). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Jankowski, J. J., Rose, S. A. & Feldman, J. F. Modifying the

distribution of attention in infants. _Child Dev._ 72, 339–351 (2001). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Colombo, J., Mitchell, D. W., Coldren, J. T. & Freeseman, L. J. Individual

differences in infant visual attention: are short lookers faster processors or feature processors? _Child Dev._ 62, 1247–1257 (1991). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hou, X. &

Zhang, L. Saliency detection: a spectral residual approach. in _2007 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition_ 1–8 (IEEE). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2007.383267 (2007).

* Itti, L. & Koch, C. A saliency-based search mechanism for overt and covert shifts of visual attention. _Vis. Res._ 40, 1489–1506 (2000). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Gartstein, M. A. & Rothbart, M. K. Studying infant temperament via the Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire. _Infant Behav. Dev._ 26, 64–86 (2003). Article Google Scholar * Rothbart,

M. K., Derryberry, D. & Hershey, K. Stability of temperament in childhood: laboratory infant assessment to parent report at seven years. in _Temperament and Personality Development

Across the Life Span_ 85–119 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2000). * Colombo, J. & Cheatham, C. L. The emergence and basis of endogenous attention in infancy and early

childhood. _Adv. Child Dev. Behav._ 34, 283–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2407(06)80010-8 (2006). * Hendry, A. et al. Developmental change in look durations predicts later effortful

control in toddlers at familial risk for ASD. _J. Neurodev. Disord._ 10, 3 (2018). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gartstein, M. A., Bridgett, D. J., Young, B. N.,

Panksepp, J. & Power, T. Origins of effortful control: infant and parent contributions. _Infancy_ 18, 149–183 (2013). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Carter, A. S., Briggs-Gowan, M.

J., Jones, S. M. & Little, T. D. The Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): factor structure, reliability, and validity. _J. Abnorm. Child Psychol._ 31, 495–514 (2003).

Article PubMed Google Scholar * Karabekiroglu, K., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Carter, A. S., Rodopman-Arman, A. & Akbas, S. The clinical validity and reliability of the Brief Infant–Toddler

Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA). _Infant Behav. Dev._ 33, 503–509 (2010). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M. & Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal

depression. _Br. J. Psychiatry_ 150, 782–786 (1987). Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Werchan, D. M., Lynn, A., Kirkham, N. Z. & Amso, D. The emergence of object‐based visual

attention in infancy: a role for family socioeconomic status and competing visual features. _Infancy_ 24, 752–767. https://doi.org/10.1111/infa.12309 (2019). * Peugh, J. L. & Enders, C.

K. Missing data in educational research: a review of reporting practices and suggestions for improvement. _Rev. Educ. Res._ 74, 525–556 (2004). Article Google Scholar * Welch, M. G.

Calming cycle theory: the role of visceral/autonomic learning in early mother and infant/child behaviour and development. _Acta Paediatrica_ 105, 1266–1274. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13547

(2016). * Belsky, J. & van IJzendoorn, M. H. Genetic differential susceptibility to the effects of parenting. _Curr. Opin. Psychol._ 15, 125–130 (2017). Article PubMed Google Scholar

* Ellis, B. J. & Boyce, W. T. Biological sensitivity to context. _Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci._ 17, 183–187 (2008). Article Google Scholar * Menon, V. Large-scale brain networks and

psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. _Trends Cogn. Sci._ 15, 483–506 (2011). Article PubMed Google Scholar * Hendry, A. et al. Developmental change in look durations predicts

later effortful control in toddlers at familial risk for ASD. _J. Neurodev. Disord._ 10, 1–14 (2018). Article Google Scholar * Hendry, A. et al. Atypical development of attentional

control associates with later adaptive functioning, autism and ADHD traits. _J. Autism Dev. Disord._ 50, 4085–4105 (2020). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Gliga, T. et al.

Enhanced visual search in infancy predicts emerging autism symptoms. _Curr. Biol._ 25, 1727–1730 (2015). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Briggs-Gowan, M. J. &

Carter, A. S. Applying the Infant-Toddler Social & Emotional Assessment (ITSEA) and Brief-ITSEA in early intervention. _Infant Ment. Health J._ 28, 564–583 (2007). Article PubMed

Google Scholar * Werchan, D. M., Brandes‐Aitken, A. & Brito, N. H. Signal in the noise: dimensions of predictability in the home auditory environment are associated with neurobehavioral

measures of early infant sustained attention. _Dev. Psychobiol._ 64, e22325 (2022). Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Werchan, D. M. & Amso, D. Top-down knowledge

rapidly acquired through abstract rule learning biases subsequent visual attention in 9-month-old infants. _Dev. Cogn. Neurosci._ 42, 100761 (2020). Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central

Google Scholar * Richards, J. E. & Anderson, D. R. Attentional inertia in children’s extended looking at television. _Adv. Child Dev. Behav._ 32, 163–212.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2407(04)80007-7 (2004). * Ludwig, R. J., & Welch, M. G. How babies learn: The autonomic socioemotional reflex. _Early Human Development_ 151, 105183.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105183 (2020). * Kingsbury, M. A., & Bilbo, S. D. The inflammatory event of birth: How oxytocin signaling may guide the development of the brain

and gastrointestinal system. _Front Neuroendocrinol._, 55, 100794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.100794 (2019). * Carter, C. S., & Kingsbury, M. A. Oxytocin and oxygen: the

evolution of a solution to the ‘stress of life.’ _Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B_ 377 https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0054 (2022). * Hane, A. A. et al. The Welch Emotional Connection Screen:

validation of a brief mother-infant relational health screen. _Acta Paediatrica_ 108, 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14483 (2029). Download references FUNDING This work was funded by

NIH R01MH125870 and the NYU COVID Catalyst grant (to N.H.B.), NIH R01MH126468 (to M.E.T.), and by a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain and Behavior Foundation (to D.M.W.). AUTHOR

INFORMATION Author notes * These authors contributed equally: Moriah E. Thomason, Natalie H. Brito. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, NYU Langone,

New York, NY, USA Denise M. Werchan, Cassandra L. Hendrix & Moriah E. Thomason * Department of Applied Psychology, New York University, New York, NY, USA Amy M. Hume, Margaret Zhang

& Natalie H. Brito Authors * Denise M. Werchan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Cassandra L. Hendrix View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Amy M. Hume View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Margaret Zhang View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Moriah E. Thomason View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Natalie

H. Brito View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CONTRIBUTIONS D.M.W., C.L.H., M.E.T. and N.H.B. conceptualized the study questions. D.M.W.

analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with input from C.L.H., N.H.B. and M.E.T. A.M.H. and M.Z. collected and coded data. D.M.W., C.L.H. and M.E.T. revised the manuscript. CORRESPONDING

AUTHOR Correspondence to Denise M. Werchan. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no competing interests. ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE The Institutional

Review Board at NYU Langone Health approved all study protocols, and informed written consent was obtained electronically prior to testing. Each participant provided informed consent prior

to participation. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION PUBLISHER’S NOTE Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. RIGHTS AND

PERMISSIONS Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s);

author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law. Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS

ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Werchan, D.M., Hendrix, C.L., Hume, A.M. _et al._ Effects of prenatal psychosocial stress and COVID-19 infection on infant attention and socioemotional

development. _Pediatr Res_ 95, 1279–1287 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02807-8 Download citation * Received: 15 February 2023 * Revised: 15 June 2023 * Accepted: 20 July 2023 *

Published: 27 September 2023 * Issue Date: April 2024 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02807-8 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this

content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative