- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT This study addressed the hypothesis that the delayed impairment in cerebral energy metabolism that develops 10-24 h after transient hypoxia-ischemia in the developing brain is

mediated by induction of increased nitric oxide synthesis. Four groups of 14-d-old Wistar rat pups were studied. Group 1 was subjected to unilateral carotid artery ligation and hypoxia

followed immediately by treatment with the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor, _N_ω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME, 30 mg/kg). Group 2 underwent hypoxia-ischemia but received

saline vehicle. Group 3 received L-NAME without hypoxia-ischemia, and group 4, saline vehicle alone. At defined times after insult, the expression of neuronal and inducible NOS were

determined and calcium-dependent and -independent NOS activities measured. Cerebral energy metabolism was observed using 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. At 48 h after insult, the

expression of inducible NOS increased, whereas neuronal NOS at 24 h decreased on the infarcted side. Calcium-dependent NOS activity was higher than calcium-independent NOS activity, but did

not increase within 36 h after insult, and was significantly inhibited by the administration of L-NAME. However, L-NAME did not prevent delayed impairment of cerebral energy metabolism or

ameliorate infarct size. These results suggest that the delayed decline in cerebral energy metabolism after hypoxia-ischemia in the 14-d-old rat brain is not mediated by increased nitric

oxide synthesis. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS COMPLEXIN 2 CONTRIBUTES TO THE PROTECTIVE EFFECT OF NAD+ ON NEURONAL SURVIVAL FOLLOWING NEONATAL HYPOXIA-ISCHEMIA Article 17 April

2025 ATTENUATED SUCCINATE ACCUMULATION RELIEVES NEURONAL INJURY INDUCED BY HYPOXIA IN NEONATAL MICE Article Open access 28 March 2022 SILDENAFIL IMPROVES HIPPOCAMPAL BRAIN INJURIES AND

RESTORES NEURONAL DEVELOPMENT AFTER NEONATAL HYPOXIA–ISCHEMIA IN MALE RAT PUPS Article Open access 11 November 2021 MAIN Transient HI to the developing brain leads to biphasic impairment in

energy metabolism; an initial decline in high-energy phosphates during HI is reversed on resuscitation, but in subjects who develop significant cerebral injury, a second phase of

dephosphorylation begins some 10-24 h after the insult(1–4). Delayed energy failure is often associated with normal or increased cerebral perfusion(5) and normal or slightly increased

pHi(6), distinguishing it from acute HI in which pHi falls significantly. Delayed cerebral energy failure has been demonstrated after HI in newborn piglets, fetal sheep, rat pups, and human

infants(2–4,7). The magnitude of the delayed impairment in cerebral energy metabolism is directly related to the severity of later neurodevelopmental impairment in newborn infants(6), the

degree of neuronal death in newborn piglets(8), and infarct size in rat pups(4). The mechanisms underlying delayed energy failure are unclear, but some evidence suggests that excessive

production of NO may be involved(9–12). NO production increases after HI(13,14), and studies show that NO can act as a potent inhibitor of mitochondrial function(15). iNOS RNA expression and

iNOS activity increase in adult animals from 12 h after focal ischemia(16,17), and transgenic mice deficient in nNOS show decreased neuronal injury after middle cerebral artery

occlusion(18–20). However, the use of NOS inhibitors to ameliorate HI injury have produced variable results(21). Thus, the role of NO in cerebral HI remains unclear. Here, we have

investigated the hypothesis that NO synthesis and NOS activity is related to the delayed impairment in cerebral energy metabolism and infarction after transient HI to the developing brain.

The neuronal and endothelial isoforms of NOS are calcium-dependent enzymes that produce picomolar concentrations of NO in rapid, short-lived bursts, whereas activation of iNOS, which is

expressed after injury, causes the sustained production of higher concentrations of NO in a calcium-independent process(21,22). This led us to the secondary hypothesis that any increase in

NO synthesis is caused by induction of calcium-independent NOS. This study used an established model of cerebral HI in 14-d-old Wistar rat pups, which have a developmental age similar to

term newborn infants(23) and are known to express all forms of NOS in the brain(24). Focal HI in these animals induces delayed impairment of cerebral energy metabolism similar to that seen

in newborn infants(4). Immunohistochemistry was used to determine the cerebral expression of iNOS and nNOS after HI and to detect microglial cells (which express iNOS) after injury(25). The

specific activities of calcium-dependent and -independent NOS were measured in normal tissue and after HI, with or without treatment with the nonspecific NOS antagonist L-NAME. In parallel

studies, phosphorus 31P MRS was used to determine the effects of NOS inhibition on cerebral energy metabolism and pHi after HI. Finally, neuropathologic examination and planimetry were used

to test whether NOS inhibition reduced the size of cerebral infarction. METHODS _ANIMAL EXPERIMENTS._ Wistar rat dams and their litters (Harlan UK Ltd, Oxford, UK) were maintained on a 12-h

cycle of light and dark in an environmental temperature of 22-23°C, with food and water freely available. Pups aged 14 d and weighing 25-34 g were removed from the litters for preparation

and study, and returned to their dams in the intervals between. _INDUCTION OF HI._ All animal procedures were approved by the Biological Services Unit Advisory Group, University of London,

and specifically licensed under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 (UK). Anesthesia was induced and maintained with isoflurane (4-5% and 1-2%, respectively) in oxygen/air (1:1).

Experimental animals underwent ventral midline cervical incision and permanent right carotid artery ligation, the procedure lasting 5-8 min. Subjects were then placed in a Perspex box within

a standard neonatal incubator (Vickers plc, Exeter, UK) at 34 +/- 0.5°C with a relative humidity of > 90% in air, following the method previously described for inducing HI injury in

21-d-old rats(26). After 60 min, hypoxia was induced by rapidly replacing the air in the incubator with 8% oxygen/92% nitrogen for 90 min at the same temperature and humidity. _EXPERIMENTAL

GROUPS._ Four experimental groups were examined: group 1 was subjected to HI and treated by intraperitoneal injection of L-NAME (30 mg/kg in 0.9% saline) immediately after the hypoxic

period. Group 2 underwent HI and received a similar volume by body weight of 0.9% saline vehicle. Group 3 received a dose of L-NAME (30 mg/kg) without being subjected to HI, and group 4 was

treated with saline vehicle without undergoing HI. At least one animal from each litter was assigned to each of the groups studied. _IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY._ For immunohistochemical analysis,

20 animals were studied after HI injury (group 2), and five were studied as controls (group 4). Animals were killed by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbitone at 6, 24, or 48 h or 5 d

after hypoxia, and then fixed by transcardial perfusion with 20-25 mL of 0.9% NaCl followed by 20-25 mL of 1% paraformaldehyde in 0.9% NaCl. Brains were dissected out and placed in 1%

paraformaldehyde for 6 h at 4°C, then transferred to 15% sucrose/PBS overnight. Brains were placed on cork, coated with TCF, and frozen immediately in isopentane cooled in liquid nitrogen.

Sections (thickness 7 µm) were cut on a cryostat, at a point corresponding to between 2.6 and 3.2 mm anterior to the interaural line for a 21-d-old pup(27), which contained the volume of

interest detected by the MRS coil (see below). Antibodies to iNOS (rabbit anti-mouse iNOS; provided by Dr. T. Evans, Department of Infectious Diseases, ICSM) and nNOS (rabbit anti-rat nNOS;

supplied by Prof. J.M. Polak, Histochemistry, ICSM) and a monoclonal mouse anti-rat macrophage cell marker (clone ED1, Serotec Ltd, Oxford, UK) were used for immunostaining. After blocking

endogenous peroxidase with 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min at room temperature, sections were incubated at room temperature in either 10% normal donkey serum in PBS for 30 min (iNOS and

nNOS) or normal rabbit serum for 15 min (ED1) to reduce nonspecific background staining. The dilutions of primary antibodies were as follows: iNOS 1:1000 in 0.1% BSA/PBS at 4°C overnight;

nNOS 1:2000 in 0.1% BSA/PBS at 4°C overnight; and ED1 in PBS for 60 min at room temperature. After several washes in PBS, the sections were incubated with the following secondary antibodies:

biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Pharmacia, St. Albans, UK) 1:200 in 0.1% BSA/PBS for 30 min at room temperature (iNOS and nNOS), and horseradish peroxidase-linked rabbit

anti-mouse immunoglobulin (DAKO, High Wycombe, UK) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature (ED1). iNOS and nNOS sections were then incubated with avidin-biotin complex (Vector, Peterborough,

UK) for 30 min at room temperature. All sections were placed in diaminobenzidine reagent (0.05 mg/mL in PBS with 0.03% H2O2) for 5 min at room temperature. The intensity of staining in

cerebral cortex, hippocampus, caudate nucleus, thalamus, and habenular nucleus was independently assessed by two observers unaware of the subject's experimental group (X.Y., D.L.T.).

Semi-quantitative measurements of NOS expression were made by grading each brain area on a scale of 0 to 4 (where 0 = no positive cells, 4 = widespread intense staining). Global estimates of

staining intensity were obtained for left and right sides of the brain by summation of scores from the separate brain regions. _SPECIFIC ACTIVITY OF NOSS._ For the determination of NOS

activity, an additional 57 rat pups were studied: 15 were subjected to HI and received L-NAME (group 1); 14 underwent HI and saline vehicle (group 2); 13 received L-NAME without HI (group

3); and 15 received saline vehicle without HI. (group 4). Animals were killed at 6, 18, or 36 h after treatment, and brains were immediately removed and cut at a point corresponding to

between 2.6 and 3.2 mm anterior to the interaural line. Each 6-mm tissue section was then separated into left and right hemispheres, wrapped in aluminium foil, and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Calcium-dependent and -independent NOS activity was measured by the conversion of L-[U-14C]arginine to L-[U-14C]citrulline as described previously(28). Frozen tissue was homogenized at 0°C

in buffer (pH 7.0 at 20°C) containing 320 mM sucrose, 50 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DL-DTT, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (100 mg/mL), leupeptin (10 mg/mL), soybean trypsin inhibitor (100

mg/mL), and aprotinin (2 mg/mL). The crude homogenate was centrifuged at 0°C at 12 000 × _g_ for 20 min, the pellet was discarded, and the supernatant was placed on ice. After the addition

of L-valine (50 mM) to the reaction buffer to minimize interference from arginase, NOS activity was determined within 1 h of preparation by measuring the conversion of L-[U-14C]arginine to

L-[U-14C]citrulline. Total NOS activity was defined as the difference between untreated samples and those containing both 1 mM EGTA and 1 mM _N_ω-monomethyl-L-arginine. Calcium-independent

activity was defined as the difference between untreated samples and samples containing 1 mM EGTA. Calcium-dependent activity was calculated by subtracting calcium-independent activity from

total activity. _31__P MRS._ MRS was performed with a 7-T Bruker Biospec magnetic resonance spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) operating at 121.6 MHz. A two-turn elliptical (5 × 10 mm) surface

coil with the major axis parallel to the midline was placed on the right side of the shaved vault of the head to completely cover the expected region of cerebral damage. The volume of brain

assessed was predominantly the right forebrain hemisphere such that the anterior margin of the coil lay at a point corresponding to approximately 2 mm anterior to the bregma and the

posterior margin at a point corresponding to the lambdoid suture of the skull, to a depth of about 5 mm. The homogeneity of the static magnetic field was optimized for each subject using the

proton water signal. Fully relaxed 31P spectra were obtained using a single-pulse acquisition, a 10-s repetition time, and a 180° flip angle at the coil center. A total of 128 summed free

induction decays were obtained for each spectrum. The spectra were analyzed using semiautomatic Lorentzian fitting by C2 minimization in the frequency domain, and the relative [PCr], [NTP],

and [Pi] were calculated. The concentration ratio [PCr]/[Pi] was determined as a measure of cerebral phosphorylation potential. The NTP resonances originate almost entirely from ATP. [NTP]

was expressed relative to the [EPP], which consisted of the main high-energy phosphate-containing metabolites. [EPP] was quantified as [Pi] + [PCr] + [(α + β + γ)NTP]. pHi was calculated

from the chemical shift of Pi relative to PCr using the Henderson-Hasselbalch relationship(29) as follows: pHi = 6.77 + log[(Pi - 3.29)/(5.68 - Pi)] A total of 66 rat pups were studied: 16

were subjected to HI and treated with L-NAME (group 1); 18 underwent HI and received only saline vehicle (group 2); 12 received L-NAME without HI (group 3); and 20 received saline without HI

(group 4). An additional six animals who began the study died; two while under anesthesia in the magnet and four after magnetic resonance measurements but before sacrifice at 7 d. Three of

these animals were from group 1, two from group 2, and one from group 3. No data from these animals were included in the results. Data were collected from individual animals while they were

lightly anesthetized with isoflurane (1-2%) and gently restrained on a purpose-built nonmagnetic platform introduced into the bore of the magnetic resonance spectrometer. Baseline spectra

were obtained from five or six animals in each litter before surgery and hypoxia. In groups 1 and 2, the first spectrum after HI was acquired immediately after the hypoxic period and

intraperitoneal injection of L-NAME or saline as appropriate. Animals that did not undergo HI (groups 3 and 4) were sampled at similar time intervals. Further spectra (two to four from each

animal) were obtained during the next 48 h. _NEUROPATHOLOGIC ANALYSIS OF INFARCT SIZE._ Animals studied by MRS were killed at 7 d after HI, and fixed by transcardial perfusion with 25-30 mL

of 0.9% NaCl followed by 25-30 mL of 10% formaldehyde in 0.9% NaCl. Brains were then removed and placed in 10% formaldehyde solution. After fixation for a minimum of 5 d, specimens were

routinely dehydrated in serial alcohols and paraffin embedded before sectioning. Sections (thickness 5 µm) were cut at a point corresponding to between 2.6 and 3.2 mm anterior to the

interaural line and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Planimetry was used to quantify the extent of the infarct by a researcher unaware of the subject's experimental group (J.M.).

Images encompassing the entire section were captured using ×4 magnification, then processed using a Seescan image analyzer (Seescan PLC, Cambridge, UK). The area of infarction was delineated

manually with reference to the section at ×10 magnification, and a quantitative index of damage was derived by the following formula to take into account tissue shrinkage caused by

selective neuronal loss: (Equation 1) _STATISTICAL ANALYSIS._ Quantitative data distributions were tested for normality and equal variance, and non-Gaussian distributions were transformed

when appropriate. Data that were normally distributed and passed Bartlett's test for equal variance were analyzed using ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison test;

significance was accepted for _p_ < 0.05. Other distributions were compared using Kruskall-Wallis ANOVA, but because formal multiple comparison testing was not possible, specific further

_post hoc_ comparisons where made when necessary. Because _post hoc_ analysis might falsely inflate the chance of reaching statistical significance, _p_ values of 0.01 were required for

significance when multiple nonparametric tests were used. All calculations were performed using Stata 5.0 statistical software (Statacorp, College Station, TX). RESULTS IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY.

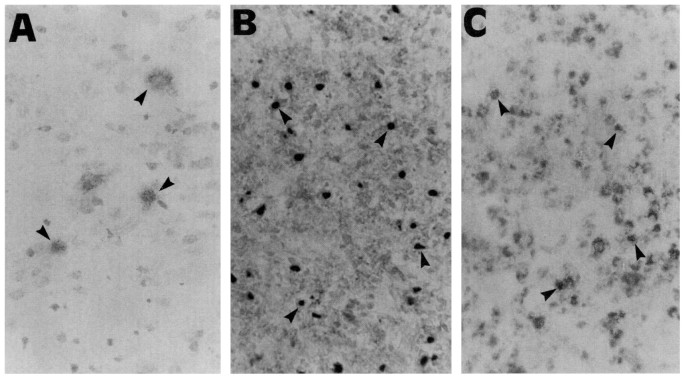

Examples of positive nNOS, iNOS, and ED1 staining are shown in Figure 1, and semiquantitative analysis of immunohistochemical results are given in Figure 2. In control animals,

nNOS-positive cells were detectable in both the injured (right) and contralateral cortex, caudate, hippocampus, and habenular nucleus. The number of nNOS-positive cells and the intensity of

staining on both sides of the brain decreased 24 h after HI (Fig. 2, _top_). After 5 d, very few nNOS-positive cells were present in the right infarcted side. The contralateral regions also

showed a decrease in nNOS-positive cells at this time, with the few remaining positive cells restricted mainly to the cortex. Small numbers of iNOS-positive cells were present in both the

left and right cortex and habenular nucleus in control tissue and at 6 h after HI. At 24 h after the insult, small numbers of iNOS-positive cells were also apparent in the caudate putamen,

hippocampus, and dorsolateral thalamus in the injured side only. At 48 h after HI, both the number of iNOS-positive cells and the intensity of staining increased further on the side of

injury in all brain areas. Similarly, at 5 d, there was intense staining of the injured side; however, the number of iNOS-positive cells in the contralateral side remained unchanged (Fig. 2,

_middle_). ED1-positive cells were not detected in controls, or at 6 and 24 h after HI (Fig. 2, _lower_). However, at 48 h, ED1-positive cells were detected in the right cortex, caudate

putamen, hippocampus, and thalamus, and at 5 d, the number increased and ED1 staining was also detected in the habenular nucleus. No ED1 staining could be detected in the contralateral brain

areas at any time. SPECIFIC ACTIVITY OF NOSS. The specific activities of calcium-dependent and -independent NOS in each group are shown in Figure 3. Data distributions were non-Gaussian,

and no satisfactory transformation could be found, so nonparametric analyses were performed. In all groups, calcium-independent NOS activity was significantly less than calcium-dependent

activity (by approximately one order of magnitude) throughout the experiment (_p_ < 0.001). There was no significant difference in NOS activity (of either isoform) between right and left

sides of the brain in any of the experimental groups at the times investigated. However, in control animals (group 4), calcium-dependent NOS activity declined with time (_p_ < 0.001).

Significantly, there was no evidence that NOS activity increased after HI. L-NAME-treated subjects had significantly less calcium-dependent NOS activity than vehicle-treated animals (_p_

< 0.001). The decline in calcium-independent activity approached but did not reach statistical significance (_p_ = 0.039). The results were similar if only the animals subjected to HI

were included in the analysis. _31__P MRS._ Data from 31P MRS studies were found to fit a skewed distribution, and the results were transformed before analysis using a zero-skewness log

transformation taking the form _y_ = 1n(_x - k_), where _y_ is the transformed variable, _x_ the original value, and _k_ a coefficient estimated by Newton's method with numeric

uncentered derivatives that allows the skewness of the transformed distribution to be close to zero: _k_ was 3.6196. ANOVA with multiple comparison testing was used after transformation. The

results of measurements of [PCr]/[Pi] and [NTP]/[EPP] from each group are given in Figure 4. Both HI groups 1 and 2 demonstrated significantly lower [PCr]/[Pi] values compared with control

groups 3 and 4 immediately after HI, with some recovery in the next 10 h, followed by a delayed decline in [PCr]/[Pi]. Neither group 3 nor 4 showed this delayed decline in [PCr]/[Pi] values.

Similarly, both groups 1 and 2 showed delayed declines in [NTP]/[EPP] after HI, whereas no such change was observed in groups 3 and 4. Multiple comparison testing showed that there was no

difference between groups 1 and 2 in values obtained > 10 h after HI, and both groups were significantly different from control groups 3 and 4 (_p_ < 0.05). Estimations of

intracellular pH are given in Table 1. No significant differences of pHi were observed between the four groups, and no significant decline in pHi was seen during the delayed fall in

[PCr]/[Pi] in groups 1 and 2. _NEUROPATHOLOGIC ASSESSMENT OF CEREBRAL INFARCTION._ The percentage area of infarction for each group is shown in Figure 5. The data were heavily skewed and no

suitable transformation could be found, so nonparametric tests were used. There was no significant difference between animals treated with L-NAME after HI (group 1) and those that received

saline vehicle after HI (group 2), but both groups had significantly larger areas of infarction than groups 3 and 4 (_p_ < 0.01), which had no histologic evidence of infarction but showed

marginal asymmetry between right and left sides with planimetry. DISCUSSION Delayed cerebral energy failure after HI is associated with impaired mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and

increased intracellular redox potential(2,30), which manifest as low [PCr]/[Pi], increased cerebral lactate concentrations, and normal or increased pHi. NOS specific activity is present in

the 14-d-old rat brain(24,31,32), and NO production is increased after HI in adults rats(33,34) and in both immature rats(14) and fetal sheep(13) after ischemia. NO is a powerful inhibitor

of mitochondrial activity _in vitro_(15), which suggested that impairment of mitochondrial function by excessive NO production might be a mechanism for delayed energy failure(15,35). The

present study confirmed the presence of both iNOS and nNOS immunoreactivity in the 14-d-old rat brain but no increases in either calcium-dependent or -independent specific NOS activities

were detected up to 36 h after HI; indeed, calcium-independent activity remained persistently low. Further, the level of iNOS protein detected by immunohistochemistry did not increase until

24-48 h after the insult, well after the onset of delayed energy failure. Finally, administration of L-NAME reduced the basal NOS specific activity to very low levels but neither ameliorated

delayed energy failure nor reduced the magnitude of cerebral infarction. It is therefore unlikely that delayed impairment in energy metabolism developing between 10 and 24 h after

resuscitation was mediated through increased NO production by either constitutive or inducible isoforms of the enzyme. The methods used in this study are well established. The MRS techniques

and equipment used were similar to, and the results consistent with, our previous studies(4). The volume of interest for MRS was predominantly localized to the region of infarction in the

right hemisphere. Measurements of specific NOS activity were made on tissue taken from the volume of interest beneath the coil and from the comparable contralateral region.

Immunohistochemistry not only provided information about the infarcted tissue but also allowed observation of global changes in NOS expression. The antibodies to iNOS and nNOS used for

immunohistochemical analysis have been shown previously to be specific(36,37); however, nNOS antibodies probably cross-react with eNOS. For this reason (and because measurements of

calcium-dependent specific activity reflected the sum of nNOS and eNOS), tissues were not stained independently for eNOS. The expression of nNOS was noted to be decreased on the

contralateral side at 1, 2, and 5 d after HI compared with control values. The reason for this is unclear inasmuch as there was no neuronal injury on this side of the brain; however, the

staining is less than in the ipsilateral (injured) hemisphere. Focal infarction in the developing rat brain is a well-characterized and widely used experimental model, in which delayed

impairment in energy metabolism has been demonstrated both by MRS and biochemical techniques(38). In the present study, we used 14-d-old rats because at this age, brain development is

largely comparable to that of the term newborn infant(23). Delayed energy failure is a prominent feature of HI injury at this stage of development, occurring in both focal and global injury.

Newborn piglets show a similar decline in high-energy phosphates after HI, and an analogous change has been found in fetal sheep after global cerebral ischemia(39). In human infants,

delayed impairment of energy metabolism has been most consistently demonstrated in term newborn infants(1,6), and interruption of the pathologic process by therapeutic intervention before

delayed impairment of energy metabolism would have clinical relevance at this age. L-NAME was chosen for the study to achieve long-lasting inhibition of both calcium-dependent and

calcium-independent NOS after a single injection. To ensure that NO production was adequately inhibited, the dose used in this study (30 mg/kg) was higher than that used in earlier

studies(40,41), although no neuropathologic damage was observed in the absence of HI. Measurement of specific NOS activity confirmed that NO production was effectively blocked before and

during the development of delayed energy failure. The effect of this inhibition did not decline during the study period. In fact, the only change observed was the time-dependent decline in

calcium-dependent NOS activity in control vehicle-treated animals (group 4), which is supported by previous findings(24). In previous studies, lower doses of L-NAME (1-10 mg/kg) were more

effective for neural rescue therapy(40,41), and it was suggested that the higher doses of L-NAME and other nonspecific inhibitors of NOS cause a fall in cerebral blood flow(18,42). However,

the following findings in the present study suggest that L-NAME did not reduce cerebral perfusion sufficiently to induce HI injury: _1_) Intracellular acidosis was not detected either in

animals treated with L-NAME and subjected to HI, nor those without. Measurement of pHi is an appropriate method for detecting significant ischemia in this setting inasmuch as intracellular

acidosis is a universal feature of severe acute HI, whereas measurements of cerebral blood flow or oxygen consumption are complicated by the pronounced changes in both these variables that

occur during delayed energy failure(2). _2_) There was no decline in [PCr]/[Pi] or [NTP]/[EPP] seen when L-NAME was administered to animals without HI. _3_) There was no evidence of

histologic damage in L-NAME-treated animals unless they had been previously subjected to HI. _4_) Our previous studies of immature animals have suggested that NO is not a major mediator of

cerebral blood flow in the developing brain; the characteristic increase in cerebral perfusion during delayed injury is only partially inhibited by NOS inhibition in fetal sheep(43), and in

newborn piglets, NO played a relatively small part in modulating cerebral blood volume and flow(44,45). Although L-NAME caused a decrease in cerebral blood flow in an adult rat MCA occlusion

model, oxygen supply was reported to improve slightly(46). These results suggest that L-NAME did not cause critical ischemia during delayed injury. Even if it had, the main conclusion of

the study, that increased NO production is not the main mediator of delayed impairments in energy metabolism after HI, would remain unchanged. Studies of adult animals have found that iNOS

mRNA and enzymatic activity are most marked 48 h after ischemia and that iNOS immunoreactivity is abundant by 4 d after ischemia(16,17). In contrast, the present study of an immature brain

showed no increase of either the calcium-dependent or -independent isoform in groups undergoing ligation and hypoxia, or in control groups with or without L-NAME for up to 36 h after injury,

by which time delayed energy failure is already established. iNOS immunoreactivity in these developing brains did not increase until 48 h after injury and was paralleled by an increase in

microglial activation. Differences in the role of NO in cerebral injury at different developmental stages have been demonstrated previously(47), and therefore our findings in the 14-d-old

rat may not be directly applicable to either more or less mature subjects. However, they do suggest that at this developmental stage, which approximates that of the newborn human infant, NO

inhibition does not mediate delayed impairment of energy metabolism. It seems likely that any protective effects of more-selective NOS inhibitors will be mediated by other mechanisms.

ABBREVIATIONS * HI: hypoxia-ischemia * NO: nitric oxide * NOS: nitric oxide synthase * nNOS: neuronal nitric oxide synthase * eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase * iNOS: inducible nitric

oxide synthase * L-NAME: _N_ω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester * pHi: intracellular pH * MRS: magnetic resonance spectroscopy * NTP: nucleotide triphosphates * PCr: phosphocreatine * Pi:

inorganic phosphate * EPP: total exchangeable phosphate pool * TCF: tissue clearing fluid REFERENCES * Hope PL, Costello AM, Cady EB, Delpy DT, Tofts PS, Chu A, Hamilton PA, Reynolds EOR,

Wilkie DR 1984 Cerebral energy metabolism studied with phosphorus NMR spectroscopy in normal and birth-asphyxiated infants. _Lancet_ 2: 366–370 Article CAS Google Scholar * Yager JY,

Brucklacher RM, Vannucci RC 1991 Cerebral oxidative metabolism and redox state during hypoxia-ischemia and early recovery in immature rats. _Am J Physiol_ 261:H1102–H1108 CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Lorek A, Takei Y, Cady EB, Wyatt JS, Penrice J, Edwards AD, Peebles D, Wylezinska M, Owen-Reece H, Kirkbride V, Cooper C, Aldridge RF, Roth SC, Brown G, Delpy DT, Reynolds EOR

1994 Delayed ("secondary") cerebral energy failure after acute hypoxia-ischemia in the newborn piglet: continuous 48-hour studies by phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

_Pediatr Res_ 36: 699–706 Article CAS Google Scholar * Blumberg RM, Cady EB, Wigglesworth JS, McKenzie JE, Edwards AD 1997 Relation between delayed impairment of cerebral energy

metabolism and infarction following transient focal hypoxia-ischaemia in the developing brain. _Exp Brain Res_ 113: 130–137 Article CAS Google Scholar * Marks KA, Mallard EC, Roberts I,

Williams CE, Sirimanne ES, Johnston B, Gluckman PD, Edwards AD 1996 Delayed vasodilation and altered oxygenation after cerebral ischemia in fetal sheep. _Pediatr Res_ 39: 48–54 Article CAS

Google Scholar * Azzopardi D, Wyatt JS, Cady EB, Delpy DT, Baudin J, Stewart AL, Hope PL, Hamilton PA, Reynolds EOR 1989 Prognosis of newborn infants with hypoxic-ischemic brain injury

assessed by phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy. _Pediatr Res_ 25: 445–451 Article CAS Google Scholar * Williams CE, Gunn A, Gluckman PD 1991 Time course of intracellular edema and

epileptiform activity following prenatal cerebral ischemia in sheep. _Stroke_ 22: 516–521 Article CAS Google Scholar * Yue X, Mehmet H, Penrice J, Cooper C, Cady E, Wyatt JS, Reynolds

EO, Edwards AD, Squier MV 1997 Apoptosis and necrosis in the newborn piglet brain following transient cerebral hypoxia-ischaemia. _Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol_ 23: 16–25 Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Nowicki JP, Duval D, Poignet H, Scatton B 1991 Nitric oxide mediates neuronal death after focal cerebral ischemia in the mouse. _Eur J Pharmacol_ 204: 339–340 Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dawson VL, Dawson TM, London ED, Bredt DS, Snyder SH 1991 Nitric oxide mediates glutamate neurotoxicity in primary cortical cultures. _Proc Natl Acad Sci USA_

88: 6368–6371 Article CAS Google Scholar * Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Bartley DA, Uhl GR, Snyder SH 1993 Mechanisms of nitric oxide-mediated neurotoxicity in primary brain cultures. _J

Neurosci_ 13: 2651–2661 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dawson VL, Dawson TM 1996 Nitric oxide neurotoxicity. _J Chem Neuroanat_ 10: 179–190 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar *

Tan WK, Williams CE, During MJ, Mallard CE, Gunning MI, Gunn AJ, Gluckman PD 1996 Accumulation of cytotoxins during the development of seizures and edema after hypoxic-ischemic injury in

late gestation fetal sheep. _Pediatr Res_ 39: 791–797 Article CAS Google Scholar * Thoresen M, Satas S, Puka-Sandvall M, Whitelaw A, Hallstrom A, Loberg E-M, Ungerstedt U, Steen PA,

Hagberg H 1997 Post-hypoxic hypothermia reduces cerebrocortical release of NO and excitotoxins. _Neuroreport_ 8: 3359–3362 Article CAS Google Scholar * Brown GC, Cooper CE 1994 Nanomolar

concentrations of nitric oxide reversibly inhibit synaptosomal respiration by competing with oxygen at cytochrome oxidase. _FEBS Lett_ 356: 259–298 Article Google Scholar * Iadecola C, Xu

X, Zhang F, et al Fakahany EE, Ross ME 1995 Marked induction of calcium-independent nitric oxide synthase activity after focal cerebral ischemia. _J Cereb Blood Flow Metab_ 15: 52–59 Article

CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Iadecola C, Zhang F, Xu S, Casey R, Ross ME 1995 Inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression in brain following cerebral ischemia. _J Cereb Blood Flow

Metab_ 15: 378–384 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Huang Z, Huang PL, Panahian N, Dalkara T, Fishman MC, Moskowitz MA 1994 Effects of cerebral ischemia in mice deficient in neuronal

nitric oxide synthase. _Science_ 265: 1883–1885 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Ferriero DM, Holtzman DM, Black SM, Sheldon RA 1996 Neonatal mice lacking neuronal nitric oxide

synthase are less vulnerable to hypoxic-ischemic injury. _Neurobiol Dis_ 3: 64–71 Article CAS Google Scholar * Panahian Y, Yoshida T, Huang PL, Hedley Whyte ET, Dalkara T, Fishman MC,

Moskowitz MA 1996 Attenuated hippocampal damage after global cerebral ischemia in mice mutant in neuronal nitric oxide synthase. _Neuroscience_ 72: 343–354 Article CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Samdani AF, Dawson TM, Dawson VL 1997 Nitric oxide synthase in models of focal ischemia. _Stroke_ 28: 1283–1288 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Forstermann U, Schmidt

HHHW, Pollock JS, Sheng H, Mitchell JA, Warner TD, Nakane M, Murad F 1991 isoforms of nitric oxide synthase-characterization and purification from different cell types. _Biochem Pharmacol_

42: 1849–1857 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Romijn HJ, Hofman MA, Gramsbergen A 1991 At what age is the developing cerebral cortex of the rat comparable to that of the full-term

newborn human baby?. _Early Hum Dev_ 26: 61–67 Article CAS Google Scholar * Lizasoain I, Weiner CP, Knowles RG, Moncada S 1996 The ontogeny of cerebral and cerebellar nitric oxide

synthase in the guinea pig and rat. _Pediatr Res_ 39: 779–783 Article CAS Google Scholar * Chao CC, Hu S, Molitor TW, Shaskan EG, Peterson PK 1992 Activated microglia mediate neuronal

cell injury via a nitric oxide mechanism. _J Immunol_ 149: 2736–2741 CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Sirimanne ES, Guan J, Williams CE, Gluckman PD 1994 Two models for determining the

mechanisms of damage and repair after hypoxic-ischaemic injury in the developing rat brain. _ethods_ 55: 7–14 CAS Google Scholar * Sherwood NM, Timiras PS 1970 A Stereotaxic Atlas of the

Developing Rat Brain. University of California Press, Berkley, CA, pp 23–48 * Salter M, Knowles RG, Moncada S 1991 Widespread tissue distribution, species distribution and changes in

activity of Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent nitric oxide synthases. _FEBS Lett_ 291: 145–149 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Petroff OA, Prichard JW, Behar KL, Alger JR, den

Hollander JA, Shulman RG 1985 Cerebral intracellular pH by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. _Neurology_ 35: 781–788 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Robertson NJ, Cox IJ,

Counsell S, Cowan F, Azzopardi D, Edwards AD 1998 Persistent lactate following perinatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy and its relationship to energy failure studied by magnetic resonance

spectroscopy. _Early Hum Dev_ 5: 73 Google Scholar * Matsumoto T, Pollock JS, Nakane M, Forstermann U 1993 Developmental changes of cytosolic and particulate nitric oxide synthase in rat

brain. _Brain Res Dev Brain Res_ 73: 199–203 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Keilhoff G, Seidel B, Noack H, Tischmeyer W, Stanek D, Wolf G 1996 Patterns of nitric oxide synthase at

the messenger RNA and protein levels during early rat brain development. _Neuroscience_ 75: 1193–1201 Article CAS Google Scholar * Higuchi Y, Hattori H, Hattori R, Furusho K 1996

Increased neurons containing neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the brain of a hypoxic-ischemic neonatal rat model. _Brain Dev_ 18: 369–375 Article CAS Google Scholar * Shibata M, Araki N,

Hamada J, Sasaki T, Shimazu K, Fukuuchi Y 1996 Brain nitrite production during global ischemia and reperfusion: an _in vivo_ microdialysis study. _Brain Res_ 734: 86–90 Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Bolanos JP, Almeida A, Stewart V, Peuchen S, Land JM, Clark JB, Heales SJ 1997 Nitric oxide-mediated mitochondrial damage in the brain: mechanisms and implications for

neurodegenerative diseases. _J Neurochem_ 68: 2227–2240 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Buttery LD, Evans TJ, Springall DR, Carpenter A, Cohen J, Polak JM 1994 Immunochemical

localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase in endotoxin-treated rats. _lab Invest_ 71: 755–764 CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Springall DR, Riveros-Moreno V, Buttery L, Suburo A, Bishop

AE, Merrett M, Moncada S, Polak JM 1992 Immunological detection of nitric oxide synthase(s) in human tissues using heterologous antibodies suggesting different isoforms. _Histochemistry_

98: 259–266 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yager JY, Brucklacher RM, Vannucci RC 1992 Cerebral Energy metabolism during hypoxia-ischemia and elderly recovery in immature rats. _Am J

Physiol_ 262:H672–H677 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Williams CE, Gunn AJ, Mallard C, Gluckman PD 1992 Outcome after ischemia in the developing sheep brain: an

electroencephalographic and histological study. _Ann Neurol_ 31: 14–21 Article CAS Google Scholar * Ashwal S, Cole DJ, Osborne S, Osborne TN, Pearce WJ 1995 L-NAME reduces infarct volume

in a filament model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat pup. _Pediatr Res_ 38: 652–656 Article CAS Google Scholar * Anderson RE, Meyer FB 1996 Nitric oxide synthase

inhibition by L-NAME during repetitive focal cerebral ischemia in rabbits. _Am J Physiol_ 271:H588–H594 CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Dalkara T, Yoshida T, Irikura K, Moskowitz MA 1994 Dual

role of nitric oxide in focal cerebral ischemia. _Neuropharmacology_ 33: 1447–1452 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Marks KA, Mallard CE, Roberts I, Williams CE, Gluckman PD, Edwards

AD 1996 Nitric oxide synthase inhibition attenuates delayed vasodilation and increases injury after cerebral ischemia in fetal sheep. _Pediatr Red_ 40: 185–191 Article CAS Google Scholar

* Takei Y, Edwards AD, Lorek A, Peebles DM, Belai A, Cope M, Delpy DT, Reynolds EOR 1993 Effects of _N_ω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester on the cerebral circulation of newborn piglets

quantified in vivo by near-infrared spectroscopy. _Pediatr Res_ 34: 354–359 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Patel K, Pryds O, Roberts I, Harris D, Edwards D 1996 Limited role for

nitric oxide in mediating cerebrovascular control of newborn piglets. _Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed_ 75:F82–F86 Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Wei HM, Chi OZ,

Liu X, Sinha AK, Weiss HR 1994 Nitric oxide synthase inhibition alters cerebral blood flow and oxygen balance in focal cerebral ischemia in rats. _Stroke_ 25: 445–449 Article CAS PubMed

Google Scholar * Tasker RC, Sahota SK, Williams SR 1996 Bioenergetic recovery following ischemia in brain slices studied by 31P NMR spectroscopy: differential age effect of depolarization

mediated by endogenous nitric oxide. _J Cereb Blood Flow Metab_ 16: 125–133 Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank Dr. T. Evans

and Prof. J. Polak (ICSM, Hammersmith Hospital, London) for generously supplying the antibodies used in this study. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Division of Paediatrics,

Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Imperial College School of Medicine, Hammersmith Hospital, London, W12, UK Raoul M Blumberg, Deanna L Taylor, Xu Yue, Huseyin Mehmet & A David Edwards *

Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, University of Maryland, Baltimore, 21201-1559, Maryland, USA Kripamoy Aguan & Carl P Weiner * Department of Medical

Physics, University College, London, WC1E, UK Ernest B Cady * Department of Anatomy, Charing Cross and Westminster Medical School, London, W6, UK Jeanette McKenzie Authors * Raoul M Blumberg

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Deanna L Taylor View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Xu Yue View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Kripamoy Aguan View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Jeanette McKenzie View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ernest B Cady View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Carl P Weiner View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Huseyin Mehmet View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar * A David Edwards View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Supported by the Wellcome

Trust (grant No. 038919). RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Blumberg, R., Taylor, D., Yue, X. _et al._ Increased Nitric Oxide Synthesis Is

Not Involved in Delayed Cerebral Energy Failure following Focal Hypoxic-Ischemic Injury to the Developing Brain. _Pediatr Res_ 46, 224–231 (1999).

https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199908000-00016 Download citation * Received: 17 September 1998 * Accepted: 05 March 1999 * Issue Date: 01 August 1999 * DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1203/00006450-199908000-00016 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is

not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative