- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

You have full access to this article via your institution. Download PDF KEY PATENT-RELATED EVENTS OF THE PAST 10 YEARS To celebrate the 10-year anniversary of _Nature Reviews Drug

Discovery_, we asked our patent advisors for their views on the most noteworthy patent-related events of the past decade. JAPAN According to John A. Tessensohn, an attorney specializing in

pharmaceutical patent litigation at Shusaku Yamamoto, Osaka, Japan, the most important patent case centres on so-called 'patent term extensions'. These are periods of time — of up

to 5 years in Japan — that can be added to the length of a patent to compensate for any delay in marketing the invention that is caused by the time taken to gain regulatory approval for a

drug. “The landmark Supreme Court decision in Takeda Chemical Industries versus the Japan Patent Office made it possible to obtain a patent term extension for a new form (for example, a

tablet) of a previously approved medicine (for example, an injectable form) if the pre-approved form is not covered by the patent in question,” he says. Takeda owns a patent (JP3134187) that

describes a sustained release formulation of morphine. The company was originally denied an extension of this patent, because an extension had already been granted for a different

formulation of morphine, albeit one that was not described in this patent. But on 28 April 2011, the Supreme Court ruled that the '187 patent was eligible for a patent term extension.

This was because Takeda would need to obtain regulatory approval to market the sustained release formulation. “Innovator pharmaceutical companies that apply for patents in Japan have warmly

welcomed this Supreme Court decision,” says Tessensohn, “because it will provide extended patent protection on novel formulations of previously approved active pharmaceutical ingredients.”

Another noteworthy case, which was decided in 2005, relates to the requirement that patents claiming pharmaceutical inventions need to contain pharmacological or therapeutic data. “This case

established the hardline rule that if the patent — as originally filed — does not use pharmacological data to describe the claimed pharmaceutical composition, then the patent is not

recognized as being 'enabled', and so is not permissible,” explains Tessensohn. The case revolved around a patent owned by Astellas Pharma that described the use of a

pyrazolopyridine compound for the treatment of dialysis-induced hypotension. The Intellectual Property High Court of Japan ruled that even if a patent provides a detailed explanation of the

pharmaceutical invention and its activity, without pharmacological data this description is insufficient to determine whether the compound can be used to treat dialysis-induced hypotension.

Furthermore, Tessensohn highlights that submitting pharmacological data after a patent application has been filed cannot overcome the rejection of the application. “This requirement has

eviscerated many foreign and Japanese pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical inventions — for example, Bristol-Myers Squibb's anticancer paclitaxel formulation and Pfizer's

pyrrolidine derivative,” he concludes. EU AND THE UNITED KINGDOM > There has been an increasing trend for the courts within the United > Kingdom to try to ensure that their patent

practice is in line with > that of the European Patent Office Philip Webber, a patent attorney specializing in patents related to biotechnology at Dehns, London, UK, notes that over the

past decade there has been an increasing trend for the courts within the United Kingdom to try to ensure that their patent practice is in line with that of the European Patent Office (EPO).

“Previously, there has been discord within European patent law. This is because although the EPO grants patents that have effect in the individual countries within Europe, decisions of the

Appeal Board of the EPO are not binding on the courts of these European countries,” he explains. A trend for increased harmonization is illustrated by recent UK court decisions related to a

patent on a neutrokine-α gene owned by Human Genome Sciences; the Appeal Board of the EPO found that the patent was valid. Although the UK High Court and Court of Appeal both ruled that the

corresponding UK patent was invalid, these two decisions were recently overturned in November 2011 by the UK Supreme Court. “So we can therefore expect to see the UK courts following the

patentability standards of the EPO more and more in the future,” says Webber. Webber also notes — with some dismay — that the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) is having an

increased involvement in patent cases. “Unfortunately, the CJEU is not made up of specialist patent judges and hence some of the decisions from them have been rather radical and

unpredictable.” One example he gives includes a case involving Monsanto in 2010, pertaining to the patenting of genetic material. “Prior to this case, most patent practitioners thought that

the protection afforded by a patent on a gene extended to the material in which the gene was incorporated (for example, a genetically modified organism). But the CJEU decided that patent

protection for gene sequences was only allowed when the gene is actually performing its function.” He believes that patent protection for gene sequences has been substantially reduced as a

result of this ruling by the CJEU. Another example he cites is the recent ban, based on morality grounds, on the patenting of human embryonic stem cells that are derived from the destruction

of the embryo (_Nature Rev. Drug Discov._ 10, 892–893; 2011). The recent steps towards the creation of a unitary European patent and a centralized EU patent court are also highlighted by

Webber as being particularly important developments. “After 40 years of discussion, it seems that these might soon be a reality,” he says. Currently, a patent issued by the EPO needs to be

validated (and litigated) in each individual member state that is party to the European Patent Convention. But he notes that there are still some major issues that need to be resolved, such

as the countries in which the courts might be, and the countries the judges would come from. “If a workable system is not produced, large pharmaceutical companies in particular might not use

a unitary system, and simply go back to filing national patent applications,” he cautions. UNITED STATES > There has been a shift in the past decade away from the patenting of >

pioneering basic research. According to Leslie Meyer-Leon, a patent attorney at IP Legal Strategies Group, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, who specializes in biotechnology patents, there has

been a shift in the past decade away from the patenting of pioneering basic research. “This move has been brought about by decisions of the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC)

that have changed the requirements that must be met for an invention to be considered non-obvious and to be supported by an adequate written description of the invention,” she says. She

cites the 2009 CAFC case, called 'In re Kubin' (_Nature Rev. Drug Discov._ 8, 531; 2009), which rejected a patent application filed by Amgen that claimed a cDNA sequence encoding

natural killer cell activation-inducing ligand. She explains that the CAFC held that, when the prior art supplies the requisite motivation and instructions, there is a reasonable expectation

of success in obtaining the claimed cDNA, so cloning and sequencing the cDNA is obvious, and therefore unpatentable. “In this case the CAFC reverted to a stricter standard that now has to

be met to show that a biological invention is not obvious. Previously, invalidating a patent claim as obvious required that the invention was not only obvious to try, but also that it would

have been obvious that it would succeed. In the aftermath of the In re Kubin decision, an invention can be unpatentable when it is merely obvious to try [to produce the invention], such as

when it is a product of ordinary skill and common sense rather than a product of innovation.” With regard to the requirement of written description, which states that a patent must

adequately describe what an invention is and how it is to be made and used, Meyer-Leon notes that from 1997 there was a departure — by a subset of CAFC judges — from what had been the

accepted standard for how much of a written description was sufficient for a patent to be valid. This is especially applicable in relation to patents that claim a broad genus. For example,

in this context a genus could refer to a set of vertebrate insulin cDNAs, whereas a species or member within that genus could be a human or rat insulin cDNA. Traditionally, the inventor of

the first species of a genus — for example, mouse insulin cDNA — could obtain a patent to the whole genus of vertebrate insulin cDNAs, as long as it would be fairly routine to use the mouse

cDNA to obtain the remaining members of the genus. Because the 1997 departure led to inconsistencies in how the CAFC ruled on subsequent cases involving the written description requirement,

the full-member CAFC agreed to reconcile its written description doctrine in a landmark 2010 case involving a dispute between Ariad and Eli Lilly. Although Ariad's disputed patent

claimed methods of reducing nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activity by using a broad genus of NF-κB inhibitors, it did not identify with any particularity what most of the inhibitors were. “As a

result of this case, a patent must now provide a fuller description of the various members of the genus,” explains Meyer-Leon. “Now, when a patent claims a broad genus of molecules in

functional terms (for example, a set of molecules that are capable of inhibiting a biological pathway), the patent must identify the molecules, and describe a link between them and the

inhibitory activity. Otherwise, the description is too prophetic.” She thinks that this CAFC decision will diminish the importance of so-called blocking patents. These are patents — that

have traditionally allowed broad claims to a genus — that cover new scientific ground. Prior to the Ariad case, such patents needed to be licensed to avoid patent infringement when using a

later-developed improvement to the original invention, even though the improvement was not explicitly described in the earlier patent. She highlights that as a result of this case it may not

be possible to enforce such an earlier patent against a later-developed improvement. “The impact of the Ariad case will be most acutely felt by those attempting to patent results from basic

science,” she explains. “The stricter written description requirement could invalidate many patents that describe novel, groundbreaking discoveries, such as patents typically filed by

universities.” In conclusion, Meyer-Leon feels that the heightened standards of non-obviousness and the written description requirement will require a fresh outlook when seeking patent

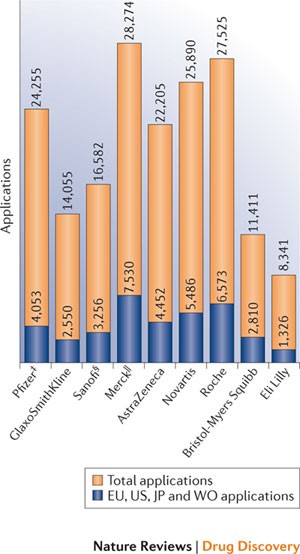

protection for biological inventions. PATENT APPLICATIONS 2002–2011 In Fig. 1 we show patent applications published in the past decade by several large pharmaceutical companies. PATENT

ADVISORS Daniel M. Becker: Dechert, Mountain View, CA, USA. Luke Kempton: Wragge & Co., London, UK. Leslie Meyer-Leon: IP Legal Strategies, Boston, MA, USA. George W. Schlich: Schlich

& Co., London, UK. John A. Tessensohn: Shusaku Yamamoto, Osaka, Japan. Philip Webber: Dehns, London, UK. Authors * Charlotte Harrison View author publications You can also search for

this author inPubMed Google Scholar RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Harrison, C. Patent watch. _Nat Rev Drug Discov_ 11, 12–13 (2012).

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3641 Download citation * Published: 03 January 2012 * Issue Date: January 2012 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3641 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative