- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

You have full access to this article via your institution. Download PDF 'Sunday Morning' designed by Ryan Frank, http://www.ryanfrank.net Industry-sponsored clinical research has

traditionally been carried out in relatively wealthy locations in North America, Western Europe and Oceania1. However, in recent years, a shift in clinical trials sponsored by the biopharma

industry to so-called emerging regions, especially in Eastern European, Latin American and Asian countries, has been noted (for example, Refs 2–5). Reasons cited for this shift include the

ability to reduce operational costs while recruiting a large number of patients in a timely manner; the establishment of contract research organizations focused on global clinical trials;

the rapid pace of growth of market size, research capacity and regulatory authority in emerging regions; and the harmonization of guidelines for clinical practice and research1,2,4,6,7. It

seems that these factors will continue to be prominent drivers of the globalization process, resulting in the solidification of trends and increased geographic dispersion of drug development

operations6. Although these trends, and the associated regulatory, public health and economic implications, have been discussed qualitatively and extensively in the literature (for example,

Refs 3,5,6,8), we are unaware of any recent Medline-indexed publications quantifying the globalization of biopharmaceutical clinical trials (BCTs; defined as trials assessing small-molecule

pharmaceuticals and adjuvants, biologics and vaccines) based on publicly accessible data. This absence reflects in part historical difficulties in accessing comprehensive public data on the

location of BCTs. However, owing to new mandates for clinical-trial registration from both the FDA and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors9,10, there has recently been a

substantial registration influx of ongoing and completed trials into ClinicalTrials.gov. As of January 2007, the site contains detailed descriptions of 36,249 recruiting and completed

studies sponsored by the public and private sectors in more than 140 countries11. These data registry developments create the opportunity for a more detailed country and region-specific

quantitative assessment of the globalization of BCTs, including clinical-trial capacity (the average number of sites per trial); trial density per population; size of trial; global span

(regional versus global); and type of trial (early versus confirmatory versus post-marketing). Key results of such an analysis, conducted as described in Supplementary information S1 (box),

are presented in Fig. 1 and Table 1, with extensive additional data available online (Supplementary information S2 (box), S3 (table), S4 (table), S5 (table), S6 (table)). This study has

several limitations, especially concerning uncertainty about the evolving coverage ratio of ClinicalTrials.gov, incompleteness of the records of some trials and its US-centric nature. It is

hoped that in the future, the public will have access to a database containing virtually complete coverage of global clinical development operations over time. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

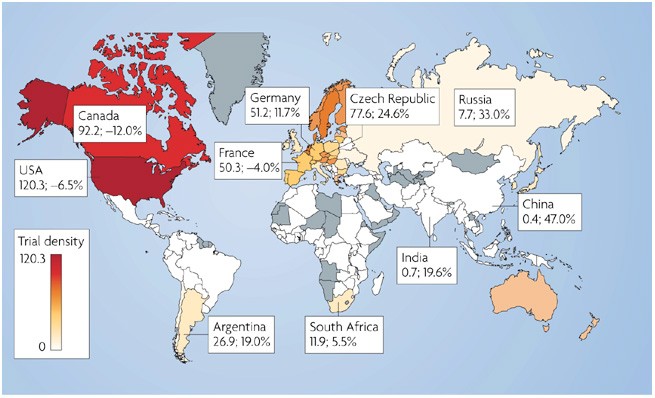

Country-specific data on trial participation reveals considerable heterogeneity across geographical regions (Fig. 1, Table 1) (Supplementary information S3 (table), S4 (table)). The US

dominates by a large margin, having more than eight times the number of trial sites than second-place Germany (Table 1). The top five countries are all in traditional regions (North America,

Western Europe and Oceania) and together host 66% of all trial sites. Countries in emerging regions (Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia, Middle East and Africa) are mostly small players

when analysed individually (each with less than 2% global share), but as a group they host 17% of actively recruiting sites. Eastern Europe and Latin America generally currently host more

sites than Asia. However, emerging nations such as India and China have grown rapidly from an almost negligible base in just several years. Their high average relative annual growth rates

(Table 1) (Supplementary information S1 (box), S4 (table)), coupled with their very low density of trials and current levels of investment in clinical research infrastructure12, suggest that

they have potential to grow into major players in the future. Not only do traditional countries tend to have more trial sites, but their trial capacity is generally larger than in emerging

economies (Table 1) (Supplementary information S3 (table), S4 (table)). Notably, a substantial number of Eastern European, Latin American and Asian nations have capacity approaching that of

the traditional regions. Although trial density (Fig. 1) is greatest in the US, Canada and in several Western European countries, it is becoming quite substantial in some Eastern European

countries such as the Czech Republic, Hungary and Estonia, but is still low in the more populous emerging countries. The fact that countries of emerging regions are reaching an average

number of sites per trial capacity comparable to that in traditional nations suggests that they are increasingly able to offer a competitive number of sites suitable to participate in large

global clinical trials. Assessing the regional distribution by trial type (Supplementary information S5 (table), S6 (table)) reveals that although North American sites comprise 56% of all

trial sites, early trials are disproportionately high in North America (62%), whereas confirmatory trials are disproportionately high in Eastern Europe, Latin America and Asia.

Post-marketing trials are disproportionately high in Western Europe, and are less frequent in North America, Eastern Europe and Latin America. In terms of growth rates, 24 of the fastest

growing 25 countries are from emerging regions (Table 1) (Supplementary information S4 (table)), while 19 of the 25 slowest growing top 50 countries are from traditional regions (Table 1)

(Supplementary information S4 (table)). Emerging regions grew from less than 8% in the BCTs initiating recruitment in 2002 to 20% of BCT sites that became active in 2006 (Supplementary

information S2 (box)). Overall, these trends have numerous public health, regulatory, economic and medical training implications. The globalization of clinical trials can bring both health

benefits and hazards to research subjects and the general population. Potential benefits include diffusion of medical knowledge and effective medical practice, and greater patient access to

high quality medical care. Concerns include the possibly inadequate regulatory oversight of research activities in emerging regions and the difficulty in drawing valid scientific conclusions

with pooled data from ethnically and culturally diverse populations. Additional areas of concern include ethical issues involving integrity of the informed consent process and suitability

of the clinical research focus, and economic impacts from the shift of geographic allocation of BCTs for the associated countries and companies3,5,6,8. REFERENCES * Rettig, R. A. The

industrialization of clinical research. _Health Aff. (Millwood)._ 19, 129–146 (2000). Article CAS Google Scholar * Olliaro, P. L. et al. Drug studies in developing countries. _Bull. World

Health Organ._ 79, 894–895 (2001). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Shah S. Globalization of clinical research by the pharmaceutical industry. _Int. J. Health Serv._ 33, 29–36

(2003). Article Google Scholar * Getz K. A. CRO contribution to drug development is substantial and growing globally. _Impact Report_ 8, 1–4 (2006). Google Scholar * Rehnquist J. The

Globalization of Clinical Trials: A Growing Challenge in Protecting Human Subjects. _Office of Inspector General Department of Health and Human Services web site_ [online], (2001). Google

Scholar * Goldbrunner, T., Doz, Y. Wilson, K. & Veldhoen, S. The Well-Designed Global R&D Network. _Strategy + Business web site_ [online], (2006). Google Scholar * International

Conference on Harmonization (ICH). E6(R1). Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guideline. _ICH web site_ [online], (1996). * International Conference on Harmonization (ICH). E5(R1). Ethnic

factors in the Acceptability of Foreign Clinical Data. _ICH web site_ http://www.ich.org/cache/compo/475-272-1.html[online], (1998). * Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Food and Drug

Administration Modernization Act (FDAMA) Section 113 and ClinicalTrials.gov. FDA web site [online], (2007). * De Angelis, C. D et al. Is this clinical trial fully registered? A statement

from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. _Lancet_ 365, 1827–1829 (2005). Article Google Scholar * Zarin, D. A. et al. Issues in the registration of clinical trials.

_JAMA_ 297, 2112–2120 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Jia, H. China beckons to clinical trial sponsors. _Nature Biotech._ 23, 768 (2005). Article CAS Google Scholar Download

references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank F. L. Douglas and H. Golub of the Harvard–MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, and M. S. Trusheim, MIT Sloan School, for comments on early

drafts. Funding: MIT's Hugh Hampton Young Memorial Fellowship (F.A.T); Louis E. Seley Chaired Professorship (E.R.B).Preliminary results described in Science Master Thesis (F.A.T)

entitled: _The Globalization of Clinical Drug Development_, submitted to the Harvard–MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology. AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Fabio A.

Thiers, Anthony J. Sinskey and Ernst R. Berndt are at the MIT Center for Biomedical Innovation, 77 Massachussetts Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA., Fabio A. Thiers, Anthony J.

Sinskey & Ernst R. Berndt * A.J.S. and E.R.B. are also at the Harvard–MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology., F.A.T., Fabio A. Thiers, Anthony J. Sinskey & Ernst R. Berndt *

A.J.S. is also at the MIT Department of Biology., Anthony J. Sinskey * E.R.B. is also at the MIT Sloan School of Management., Ernst R. Berndt Authors * Fabio A. Thiers View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Anthony J. Sinskey View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ernst R.

Berndt View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Ernst R. Berndt. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY

INFORMATION S1 (BOX) Methodology of analysis. (PDF 105 kb) SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION S2 (BOX) Recent evolution of regional shares of biopharmaceutical clinical trial sites. (PDF 140 kb)

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION S3 (TABLE) Top 50 countries Ranked by number of trial Sites – shares and trial capacity. (PDF 468 kb) SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION S4 (TABLE) Top 50 countries ranked

by average relative annual growth rates. (PDF 510 kb) SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION S5 (TABLE) Types of trial by region as of April 12, 2008 (in percent) (PDF 130 kb) SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

S6 (TABLE) Regional distribution of trial type as of April 12, 2007 (in percent) (PDF 107 kb) RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Thiers, F.,

Sinskey, A. & Berndt, E. Trends in the globalization of clinical trials. _Nat Rev Drug Discov_ 7, 13–14 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2441 Download citation * Issue Date: January

2008 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2441 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not

currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative