- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT _BRAF V600E_ mutation in serrated lesions of the colon has been implicated as an important mutation and as a specific marker for the serrated carcinogenic pathway. Recent findings

point to microvesicular hyperplastic polyps that have similar histologic and molecular features to sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, as potential colorectal carcinoma precursors. The aim of

this study was to evaluate _BRAF V600E_ mutation status by immunohistochemistry in serrated lesions of the colon with regard to histomorphology. We investigated 194 serrated lesions of the

colon, comprising 42 sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, 16 traditional serrated adenomas, 136 hyperplastic polyps and 20 tubular/tubulovillous adenomas (conventional adenomas) with the novel

_BRAF V600E_ mutation-specific antibody VE1. In addition, _BRAF_ exon 15 and _KRAS_ exon 2 status was investigated by capillary sequencing in selected cases. All sessile serrated

adenomas/polyps (42/42, 100%), 15/16 (94%) traditional serrated adenomas and 84/136 (62%) hyperplastic polyps were VE1+. None of the VE1− serrated lesions showed _BRAF V600E_ mutation. Forty

out of 42 (95%) sessile serrated adenomas/polyps displayed areas with microvesicular hyperplastic polyp-like features. In microvesicular hyperplastic polyps, VE1 positivity was

significantly associated with nuclear atypia (_P_=0.003); however, nuclear atypia was also present in VE1− cases. Immunostaining with VE1 allows not only the detection of _BRAF V600E_

mutation but also the correlation with histomorphology on a cellular level in serrated lesions. VE1 enables a subclassification of microvesicular hyperplastic polyps according to the

mutation status. This improved classification of serrated lesions including immunohistochemical evaluation of _BRAF V600E_ mutation may be the key to identify lesions with higher potential

to progression into sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, and further to _BRAF V600E_-mutated colorectal cancer. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS SMAD4 IS CRITICAL IN SUPPRESSION OF

_BRAF-V600E_ SERRATED TUMORIGENESIS Article 27 August 2021 MOLECULAR PROFILING OF SIGNET-RING-CELL CARCINOMA (SRCC) FROM THE STOMACH AND COLON REVEALS POTENTIAL NEW THERAPEUTIC TARGETS

Article 26 May 2022 ASPIRIN REDUCES THE INCIDENCE OF METASTASIS IN A PRE-CLINICAL STUDY OF _BRAF_ MUTANT SERRATED COLORECTAL NEOPLASIA Article 29 March 2021 MAIN Colorectal cancer is one of

the leading causes of cancer death worldwide. Although increased use of screening and surveillance, as well as detection and the removal of conventional adenomas, has led to a reduction in

the incidence and mortality of this disease, this effect is mainly limited to distal colorectal cancer.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 However, difficulties remain in the prevention of proximal colorectal

cancer. A recent study suggested that colorectal cancers of the proximal colon develop in a significantly shorter period of time than those in the distal colon, after a patient has had a

negative colonoscopy.2, 3 Thus, there is a need for improved and targeted identification of neoplastic precursor lesions in the proximal colon. Colorectal cancer arises from several

different types of precursor lesions. In the conventional pathway, carcinomas develop from adenomas via biallelic _APC_ (adenomatous polyposis coli) mutations6 and are reinforced by _KRAS_

mutation. In the other major pathway, known as the serrated carcinogenic pathway, tumors develop from serrated precursor lesions via _BRAF_ mutations.7, 8, 9 Serrated precursor lesions

consist of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (either with or without cytologic dysplasia) and traditional serrated adenomas.9, 10, 11, 12 Serrated lesions constitute the main precursor lesion

in at least one-third of all colorectal cancers.13, 14 Progression results in microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer and possibly also CpG island-methylated microsatellite-stable

carcinomas.3, 9, 10, 11, 12 Although consensus exists that sessile serrated adenomas/polyps and traditional serrated adenomas are colorectal cancer precursor lesions,13 hyperplastic polyps

were considered for decades to have no malignant potential. This has been questioned in the past years and different subsets of hyperplastic polyps with distinct molecular profiles and

potential to progress to colorectal cancer have been identified.15 These findings implicate that _BRAF V600E_-mutated colorectal cancers have their origin in hyperplastic polyps classified

morphologically as microvesicular hyperplastic polyps.9, 15, 16 Should this be correct, a refined classification of microvesicular hyperplastic polyps with regard to _BRAF V600E_ mutation

might lead to an improved assessment of colorectal cancer risk and guide patient management. In contrast to conventional adenomas where cytological changes have an important role in

identifying dysplasia, diagnosis of the various subclasses of serrated lesions is mainly based on the architectural criteria.17, 18 Owing to sampling issues, poor specimen orientation and a

significant interobserver variation among pathologists,19, 20, 21, 22 the differential diagnosis of microvesicular hyperplastic polyps _vs_ sessile serrated adenomas/polyps can be very

challenging or even impossible. Especially, if we consider that for the differential diagnosis of microvesicular hyperplastic polyp _vs_ sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, the presence of the

appropriate morphologic criteria in just one crypt is considered as sufficient.13 It has been suggested that _BRAF_ mutation is one of the important player in two of the five molecular

subtypes of colorectal cancer according to Jass.23 Currently, there are no established morphologic criteria that would identify oncogenic _BRAF V600E_ mutation in serrated lesions. Until

recently, assessment of _BRAF V600E_ mutation status was not feasible in routine pathology, as sequencing of all serrated lesions is not suitable for everyday diagnostic pathology. In

addition, direct sequencing might provide false-negative results owing to dilution of the diagnostic mutation through a high number of normal mucosa cells. In this regard, even

microdissection cannot give proper evidence of the distribution of cells with _BRAF V600E_ mutation within serrated lesions. The development of a novel, mutation-specific antibody has

enabled us to investigate the presence of _V600E_-mutated _BRAF_ protein in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections.24, 25, 26 The aim of this study was to evaluate BRAF V600E protein

expression in serrated lesions of the colon in correlation with morphology. The expression of BRAF V600E protein in microvesicular hyperplastic polyps (with and without nuclear atypia),

sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (with and without cytologic dysplasia) and traditional serrated adenomas should aid in subclassifying these lesions also according to their _BRAF V600E_

mutation status in addition to histomorphologic classification. In routine pathology, this would identify serrated lesions carrying the oncogenic _BRAF V600E_ mutation, which might have an

increased risk of progression to colorectal cancer. The implementation of a new classification based on distinct molecular phenotype could offer patients an individualized cancer prevention

and therapy option. MATERIALS AND METHODS TISSUE SAMPLES Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples of serrated, adenomatous

and hyperplastic colon lesions were identified in the archives of the Clinical Institute for Pathology of the Medical University of Vienna (Vienna, Austria). Samples that were improperly

oriented or did not contain sufficient amounts of tissue for further analysis were excluded from the study. Before the immunohistochemical evaluation with VE1 antibody, all tissue samples

were reviewed and histologically subclassified on hematoxylin- and eosin-stained slides according to the current WHO scheme.27 In brief, classification was based on the following criteria:

_Goblet-cell-rich hyperplastic polyp:_ comprises pure goblet cells, straight crypts with proliferative activity confined to the lower crypt, showing minimal serration. _Microvesicular

hyperplastic polyp:_ comprises epithelial cells with hypermucinous microvesicular cytoplasm only or mixed with goblet cells with maintained maturation towards the surface. Crypts are

straight, dilatation/serration is confined in the more luminal aspects, crypt bases are narrow with symmetrical proliferative activity and interspersed neuroendocrine cells. _Sessile

serrated adenoma/polyp_: The criteria for the diagnosis, as suggested by an expert panel,13 was the minimum of one crypt that clearly showed dilatation and/or serration extending to the

crypt base, with or without branching (L-, inverted T- or anchor-shape) of the crypts and abnormal proliferation (proliferative zone located on the side, frequently asymmetrical) showing

goblet cells or gastric foveolar cells in the crypt basis. In addition, absence or presence of cytologic dysplasia were determined. _Traditional serrated adenoma:_ shows villiform growth

pattern with serration due to infolding, budding and papillary tufting, composed of tall columnar cells with pencillated nucleus and hypereosinophilic cytoplasm with interspersed goblet

cells. In addition, the grade of cytologic dysplasia was determined. In total, 194 consecutive serrated lesions of the colon were included in our study, these included: 42 sessile serrated

adenomas/polyps (38 without cytologic dysplasia and 4 with cytologic dysplasia), 16 traditional serrated adenomas with low-grade dysplasia, 119 microvesicular hyperplastic polyps and 17

goblet-cell rich hyperplastic polyp. Additionally for comparison, 20 tubular/tubulovillous (conventional adenomas) with low-grade dysplasia mainly from the right colon were also included.

Mucin-poor-type hyperplastic polyps were not found in our series. Microvesicular hyperplastic polyps were evaluated for the degree of nuclear atypia according to the schema of Torlakovic _et

al._17 In addition, sessile serrated adenomas/polyps were reviewed for the presence of areas revealing a morphology of microvesicular hyperplastic polyps. The classification was carried out

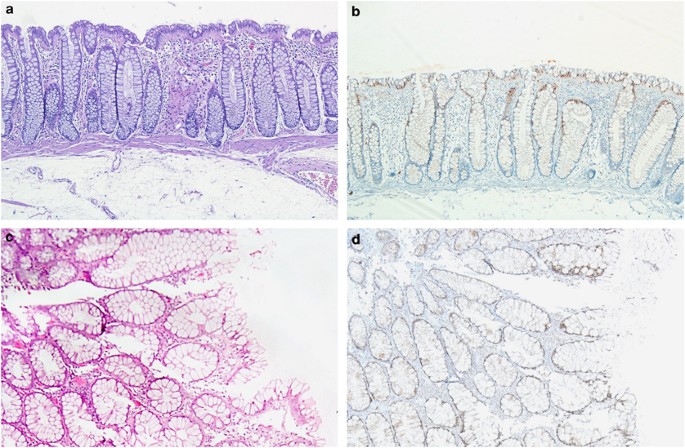

by three independent pathologists (IM, GB and PB), with consecutive consensus for each case. IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY A Benchmark ultraimmunostainer was used for immunohistochemistry (Ventana,

Tucson, AZ, USA). Expression of V600E-mutated BRAF was evaluated in 3-_μ_m-thick histological slides using the monoclonal _BRAF V600E_ mutation-specific antibody VE1 (provided by AvD, the

antibody is commercially available from Spring Bioscience, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Production and validation of this antibody has been published in detail previously.28 A specimen was

considered positive for BRAF V600E if distinct cytoplasmic staining reaction with the VE1 antibody was present (samples of immunostaining are given in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4).24, 26 Nonspecific

nuclear staining without cytoplasmic signal was detected in the surface epithelium of adjacent normal colon mucosa (Figure 1). This nuclear staining pattern has also been previously reported

in brain metastases, but in that study this type of staining showed no correlation with _BRAF_ mutation status.26 To exclude the possibility that nuclear staining pattern with VE1 in normal

mucosa corresponded to the presence of BRAF protein, cases with sufficient material available from VE1− hyperplastic polyps, which showed nonspecific nuclear staining, were immunostained

with a pan-BRAF-antibody detecting total (mutated and wild-type) BRAF (pBR1, dilution 1:4).28 In these cases, only cytoplasmic, but no nuclear, staining was evident, indicating a lack of

BRAF in the nucleus. The nuclear staining reaction did not interfere with the determination of BRAF status, as mutated BRAF protein is evident by strong cytoplasmic staining. SEQUENCE

ANALYSIS OF _KRAS_ AND _BRAF_ _BRAF_ exon 15 and _KRAS_ exon 2 (56 of 115) were investigated by capillary sequencing after macrodissection of specimens. Preparation of DNA and sequencing of

_BRAF_ exon 15 was performed as described previously.24 Briefly, a fragment spanning exon 2 of _KRAS_ (sense: 5′-GCCTGCTGAAAATGACTGAA-3′; antisense: 5′-AGAATGGTCCTGCACCAGTAA-3′) was

amplified using 20 ng each of the respective forward and reverse primer. Primer design was based on accession number NG_007524.1. For PCR, 50 ng of DNA and HotStar 2 × PCR Master Mix

(Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) were used. PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 _μ_l, and included initial denaturation at 95 °C for 180 s, followed by 37 cycles with denaturation at 95 °C

for 30 s, annealing at 56 °C for 25 s and extension at 72 °C for 40 s. Two microliters of the amplification product were submitted to bidirectional sequencing using the BigDye Terminator

v.3.1 Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Sequences were determined using an ABI 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and the Sequence-Pilot v. 3.4 (JSI-Medisys,

Kippenheim, Germany) software. STATISTICS For statistical analysis, _χ_2 tests were used as appropriate; SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for this purpose. All _P_-values given are

results from two-tailed test, a _P_-value ≤0.05 was considered as significant. RESULTS Table 1 provides details on polyp type, anatomic localization and results of VE1 immunohistochemistry,

as well as _KRAS_ sequencing in selected samples. All patients were Caucasian, of them 103 (48%) female and 111 (52%) male, median age 63 years (range 27–92 years) and mean age (years)

62±11 (s.d.). IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY In VE1+ cases, a strong granular cytoplasmic staining of the epithelial cells was present. In sessile serrated adenoma/polyp without cytologic dysplasia, a

more intense staining was detected in the basal half of the crypts compared with the superficial half. The intensity of the staining decreased continuously from the base of the crypts

towards the surface epithelium in sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, which was stronger than that in microvesicular hyperplastic polyps. In traditional serrated adenoma and in sessile serrated

adenoma/polyp with cytologic dysplasia, a diffuse strong intense staining was present with consistent strong expression continuously from the base of the crypts up to the surface epithelium.

In all VE1+ lesions (microvesicular hyperplastic polyps, traditional serrated adenomas, sessile serrated adenomas/polyps), an abrupt transition could be observed between cells with and

without _BRAF V600E_ mutation. One hundred and forty-one of 194 serrated lesions (73%) showed specific cytoplasmic staining for VE1: 100% sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, 94% of traditional

serrated adenomas and 62% of hyperplastic polyps. Of the 136 hyperplastic polyps, all 17 goblet-cell-rich hyperplastic polyps were negative for VE1 and 84 (71%) of the 119 microvesicular

hyperplastic polyps were positive for VE1. No significant difference of VE1 expression was observed between microvesicular hyperplastic polyps of the left colon compared with the right colon

(_P_>0.05, _χ_2 test; Table 2). All conventional adenomas were negative for VE1. Forty of 42 sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (95%) showed areas with histological features of

microvesicular hyperplastic polyps and a continuous positive VE1 expression, displaying significant correlation of microvesicular hyperplastic polyp-like features with _BRAF V600E_ mutation

(Table 3). Only minimal nuclear atypia (Grade 1+ according to Torlakovic _et al_17) and mild nuclear stratification was present in 75 hyperplastic polyps (55%; 75 microvesicular hyperplastic

polyps, 0 goblet-cell rich hyperplastic polyps). VE1 expression was seen in 84 (71%) of the microvesicular hyperplastic polyps, and 60 (71%) of them showed nuclear atypia (_P_=0.003, _χ_2

test). Nevertheless, 15 (43%) of the 35 VE1− microvesicular hyperplastic polyps also displayed nuclear atypia. No nuclear atypia was present in goblet-cell-rich hyperplastic polyps (Table

4). SEQUENCING FOR _BRAF_ AND _KRAS_ MUTATIONS Sequencing for _BRAF_ was performed in 30 cases, comprising 10 VE1− (8 microvesicular hyperplastic polyps, 1 traditional serrated adenoma, 1

conventional adenoma) and 20 VE1+ samples (6 sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, 9 microvesicular hyperplastic polyps, 5 traditional serrated adenoma), of which 1 microvesicular hyperplastic

polyp showed weak and heterogeneous immunostaining. All VE1− samples showed no _BRAF_ exon 15 mutation. Of the 20 VE1+ samples, 2 microvesicular hyperplastic polyps with a low number of

positive crypts were _BRAF_ wild-type at direct sequencing, but after _BRAF_ enrichment using a V600E kit (Qiagen GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany), _V600E_ mutations were evident. The remaining 17

VE1+ samples (among them also the one with weak immunostaining) showed _V600E_ mutations at direct sequencing. Interestingly, one VE1 weakly positive microvesicular hyperplastic polyp

showed _BRAF V600Q_ (c.1799_1800delinsAA) at sequencing. Sequencing for _KRAS_ was performed in 41 samples, of which 33 were VE1− (17 microvesicular hyperplastic polyp, 11 goblet-cell-rich

hyperplastic polyp, 1 traditional serrated adenoma, 4 conventional adenoma) and 8 VE1+ (4 sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, 3 microvesicular hyperplastic polyp, 1 traditional serrated

adenoma). In VE1− cases, 2 microvesicular hyperplastic polyp and 1 conventional adenoma showed _KRAS_ exon 2 mutations, whereas in the VE1+ samples, no _KRAS_ exon 2 mutations were found.

DISCUSSION The development of a _BRAF V600E_ mutation-specific antibody has enabled us to investigate for the first time the distribution of BRAF V600E protein in routine formalin-fixed,

paraffin-embedded specimens of serrated lesions of the colon. This approach allows a correlation of histomorphology with molecular pathological changes at the cellular level and an

immunohistochemical subclassification of serrated lesions according to their _BRAF V600E_ mutation status. In this study, we propose a novel and refined classification for serrated lesions

of the colon integrating histomorphology with immunohistochemical detection of _BRAF V600E_ mutation. This technique provides an objective and reproducible aid to identify serrated lesions

with the oncogenic _BRAF V600E_ mutation. _BRAF V600E_ mutation is an early event in the serrated neoplasia pathway.12 It has been anticipated that microvesicular hyperplastic polyps are the

precursor lesions for the serrated pathway and might progress into sessile serrated adenoma/polyp and to colorectal cancer.9, 15, 16 Our findings, on one hand identifying (71%)

microvesicular hyperplastic polyps with the oncogenic _BRAF V600E_ mutation and on the other hand the presence of VE1+ areas revealing the morphology of microvesicular hyperplastic polyps in

95% of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps, would favor this theory. The observed abrupt transition in all VE1+ serrated lesions between areas with and without gene mutation also indicates a

clonal evolution of the _BRAF V600E_ mutation. Generally, colorectal cancer is believed to arise on the base of distinct precursor lesions and is associated with different molecular

pathways, that is, mutation in the _KRAS_ gene (mainly in exon 2) or in the _BRAF_ gene (in the vast majority of cases the _V600E_ mutation in exon 15).14, 29, 30, 31 In our study, _BRAF

V600E_ mutation neither could be detected in goblet-cell-rich hyperplastic polyps nor in conventional adenomas. The latter fact provides evidence that _BRAF V600E_ mutation probably does not

have a major role in the conventional adenoma–carcinoma sequence, but in a subset of microsatellite-stable colorectal cancer, it has been shown that _BRAF V600E_ mutation does have a

relevant role, is prognostically significant and correlates with poorer survival.32, 33 Although consensus exists that sessile serrated adenomas are precursors of _BRAF V600E-_driven

serrated carcinoma pathway, the contribution of hyperplastic polyps is not unambiguously solved.9, 13, 15 These lesions are frequently found and ablated at routine colonoscopy. Their

neoplastic nature remains an issue of debate and many attempts have been made to find histomorphologic17 and immunomorphologic34 criteria to identify among them the neoplastic lesions, in

contrast to true hyperplastic lesions. In addition, the histological diagnosis of serrated lesions often poses a difficult task to routine pathologists: biopsy specimens are often small and

impossible to orientate. However, proper specimen orientation is crucially important for the differential diagnosis microvesicular hyperplastic polyp _vs_ sessile serrated adenoma/polyp,

which is based on architectural changes including the crypt bases. In contrast to conventional adenomas, cytological signs of dysplasia are missing in most cases of sessile serrated

adenomas/polyps. Therefore, high inter- and even intraobserver variability among pathologists is evident in the diagnosis of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps,19, 20, 21, 22 despite the

formally clear morphologic criteria.13, 17 The need for a potential marker to identify microvesicular hyperplastic polyps with risk for progression in the serrated neoplasia pathway is also

highlighted by our findings. Even though _BRAF V600E_ mutation correlated with nuclear atypia and nuclear stratification, these morphologic changes were also present in 43% of these cases in

the absence of _BRAF V600E_ mutation. These findings suggest that morphology by itself is not a reliable criterion for evaluating the presence of underlying molecular changes with regard to

_BRAF V600E_ mutation. Further problems appear by the fact, which was also evident in our study, that serrated lesions with the morphology of microvesicular hyperplastic polyps in one part

of the lesion and with the morphology of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps in the other part do exist.13 On one hand, this has been interpreted as evidence that sessile serrated

adenomas/polyps evolve from microvesicular hyperplastic polyps or on the other hand that microvesicular hyperplastic polyp features could belong to the morphologic spectrum of sessile

serrated adenomas/polyps.13 This implicates that there are borderline lesions35 and therefore no clear line can be drawn between the morphology of microvesicular hyperplastic polyps and

sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. It is likely that the progression between microvesicular hyperplastic polyp and sessile serrated adenoma/polyp is a continuum with _BRAF V600E_ mutation as

an early genetic event in the serrated neoplasia pathway. For this reason, it might generally be anticipated that microvesicular hyperplastic polyps with _BRAF V600E_ mutation are not

innocent bystanders, but indeed precursor lesions of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps finding their end point in _BRAF V600E-_mutated colorectal cancer. It might also be anticipated that

serrated lesions including microvesicular hyperplastic polyps with an already existing _BRAF V600E_ mutation have a considerable higher risk of progression to malignancy. Further clinical

studies of patients with VE1+ microvesicular hyperplastic polyps with appropriate follow-up data could possibly answer this question. As _BRAF V600E_ is also found frequently in naevi,36,

37, 38 this finding indicates that non-malignant lesions with this mutation require a ‘second hit’ to become frankly malignant. This happens obviously only in a relatively small proportion

of cases. The same scenario might be true in the development of colorectal cancer as well. In our study, _BRAF V600E_ mutation was encountered in a large percentage (62%) of hyperplastic

polyps almost equally frequent on both sides of the colon, whereas only 5–20% of colorectal cancers show _BRAF V600E_ mutation and are located more frequently in the right colon.8, 14, 29,

31 Therefore, the sole location of a lesion does not seem to be indicative of the underlying molecular pathway. However, the exact mechanisms and host-related factors contributing to further

progressions should be addressed in subsequent functional and clinical studies. In our opinion, this approach, based on immunohistochemical determination of _BRAF V600E_ mutation, is a

feasible technique in routine biopsy diagnostics, allowing unified, objective and reproducible classification of serrated lesions. This would overcome the problems of high interobserver

variability using the morphological criteria. Accordingly, microvesicular hyperplastic polyps should be subclassified with regard to _BRAF V600E_ mutation status to identify those with _BRAF

V600E_ mutation as possible precursor lesions of the serrated neoplasia pathway. Through this approach, a more elaborate classification based on the interplay between histology and

molecular pathology could offer patients an improved colorectal cancer prevention strategy. ACCESSION CODES ACCESSIONS GENBANK/EMBL/DDBJ * NG_007524.1 REFERENCES * Singh H, Turner D, Xue L

_et al_. Risk of developing colorectal cancer following a negative colonoscopy examination: evidence for a 10-year interval between colonoscopies. _JAMA_ 2006;295:2366–2373. Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Lakoff J, Paszat LF, Saskin R _et al_. Risk of developing proximal versus distal colorectal cancer after a negative colonoscopy: a population-based study. _Clin

Gastroenterol Hepatol_ 2008;6:1117–1121 quiz 064. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Jass JR . Serrated adenoma of the colorectum and the DNA-methylator phenotype. _Nat Clin Pract Oncol_

2005;2:398–405. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V _et al_. Protection from right- and left-sided colorectal neoplasms after colonoscopy:

population-based study. _J Natl Cancer Inst_ 2010;102:89–95. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF _et al_. Association of colonoscopy and death from

colorectal cancer. _Ann Intern Med_ 2009;150:1–8. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR _et al_. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. _N

Engl J Med_ 1988;319:525–532. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Huang CS, O’Brien MJ, Yang S _et al_. Hyperplastic polyps, serrated adenomas, and the serrated polyp neoplasia pathway.

_Am J Gastroenterol_ 2004;99:2242–2255. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Huang CS, Farraye FA, Yang S _et al_. The clinical significance of serrated polyps. _Am J Gastroenterol_

2010;106:229–240 quiz 41. Article PubMed Google Scholar * O’Brien MJ, Yang S, Mack C _et al_. Comparison of microsatellite instability, CpG island methylation phenotype, BRAF and KRAS

status in serrated polyps and traditional adenomas indicates separate pathways to distinct colorectal carcinoma end points. _Am J Surg Pathol_ 2006;30:1491–1501. Article PubMed Google

Scholar * Jass JR, Whitehall VL, Young J _et al_. Emerging concepts in colorectal neoplasia. _Gastroenterology_ 2002;123:862–876. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Hawkins NJ, Bariol

C, Ward RL . The serrated neoplasia pathway. _Pathology_ 2002;34:548–555. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kambara T, Simms LA, Whitehall VL _et al_. BRAF mutation is associated with DNA

methylation in serrated polyps and cancers of the colorectum. _Gut_ 2004;53:1137–1144. Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA _et al_. Serrated

lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. _Am J Gastroenterol_ 2012;107:1315–1329. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Davies H, Bignell GR,

Cox C _et al_. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. _Nature_ 2002;417:949–954. CAS PubMed Google Scholar * O‘Brien MJ . Hyperplastic and serrated polyps of the colorectum.

_Gastroenterol Clin N Am_ 2007;36:947–968. Article Google Scholar * Kim KM, Lee EJ, Ha S _et al_. Molecular features of colorectal hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenoma/polyps

from Korea. _Am J Surg Pathol_ 2011;35:1274–1286. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Torlakovic E, Skovlund E, Snover DC _et al_. Morphologic reappraisal of serrated colorectal polyps. _Am J

Surg Pathol_ 2003;27:65–81. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Snover DC, Ahnen DJ, Burt RW _et al_. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum and serrated polyposis In: Bosman FT, Carneiro

F, Hruban RH, Theise ND (eds) _WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System_ 4th edn International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2010, pp 160–165. Google Scholar *

Khalid O, Radaideh S, Cummings OW _et al_. Reinterpretation of histology of proximal colon polyps called hyperplastic in 2001. _World J Gastroenterol_ 2009;15:3767–3770. Article PubMed

PubMed Central Google Scholar * Glatz K, Pritt B, Glatz D _et al_. A multinational, internet-based assessment of observer variability in the diagnosis of serrated colorectal polyps. _Am J

Clin Pathol_ 2007;127:938–945. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Sandmeier D, Seelentag W, Bouzourene H . Serrated polyps of the colorectum: is sessile serrated adenoma distinguishable from

hyperplastic polyp in a daily practice? _Virchows Arch_ 2007;450:613–618. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Mohammadi M, Garbyal RS, Kristensen MH _et al_. Sessile serrated lesion and its

borderline variant—variables with impact on recorded data. _Pathol Res Pract_ 2011;207:410–416. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Jass JR . Classification of colorectal cancer based on

correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. _Histopathology_ 2007;50:113–130. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Koperek O, Kornauth C, Capper D _et al_.

Immunohistochemical detection of the BRAF V600E-mutated protein in papillary thyroid carcinoma. _Am J Surg Pathol_ 2012;36:844–850. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Capper D, Berghoff AS,

Deimling A _et al_. Clinical neuropathology practice news 2-2012: BRAF V600E testing. _Clin Neuropathol_ 2012;31:64–66. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Capper D, Berghoff

AS, Magerle M _et al_. Immunohistochemical testing of BRAF V600E status in 1,120 tumor tissue samples of patients with brain metastases. _Acta Neuropathol_ 2012;123:223–233. Article CAS

PubMed Google Scholar * Snover DC, Ahnen DJ, Burt RW _et al_. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum and serrated polyposis In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, (eds). _World

Health Organization Classification of Tumours_ 4th edn International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2010, pp 160–165. Google Scholar * Capper D, Preusser M, Habel A _et al_.

Assessment of BRAF V600E mutation status by immunohistochemistry with a mutation-specific monoclonal antibody. _Acta Neuropathol_ 2011;122:11–19. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Yuen

ST, Davies H, Chan TL _et al_. Similarity of the phenotypic patterns associated with BRAF and KRAS mutations in colorectal neoplasia. _Cancer Res_ 2002;62:6451–6455. CAS PubMed Google

Scholar * Velho S, Moutinho C, Cirnes L _et al_. BRAF, KRAS and PIK3CA mutations in colorectal serrated polyps and cancer: primary or secondary genetic events in colorectal carcinogenesis?

_BMC Cancer_ 2008;8:255. Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Rajagopalan H, Bardelli A, Lengauer C _et al_. Tumorigenesis: RAF/RAS oncogenes and mismatch-repair status.

_Nature_ 2002;418:934. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Samowitz WS, Sweeney C, Herrick J _et al_. Poor survival associated with the BRAF V600E mutation in microsatellite-stable colon

cancers. _Cancer Res_ 2005;65:6063–6069. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Kakar S, Deng G, Sahai V _et al_. Clinicopathologic characteristics, CpG island methylator phenotype, and

BRAF mutations in microsatellite-stable colorectal cancers without chromosomal instability. _Arch Pathol Lab Med_ 2008;132:958–964. PubMed Google Scholar * Owens SR, Chiosea SI, Kuan SF .

Selective expression of gastric mucin MUC6 in colonic sessile serrated adenoma but not in hyperplastic polyp aids in morphological diagnosis of serrated polyps. _Mod Pathol_ 2008;21:660–669.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Mohammadi M, Kristensen MH, Nielsen HJ _et al_. Qualities of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp/lesion and its borderline variant in the context of

synchronous colorectal carcinoma. _J Clin Pathol_ 2012;65:924–927. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Pollock PM, Harper UL, Hansen KS _et al_. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi.

_Nat Genet_ 2003;33:19–20. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Uribe P, Wistuba II, Gonzalez S . BRAF mutation: a frequent event in benign, atypical, and malignant melanocytic lesions

of the skin. _Am J Dermatopathol_ 2003;25:365–370. Article PubMed Google Scholar * Yazdi AS, Palmedo G, Flaig MJ _et al_. Mutations of the BRAF gene in benign and malignant melanocytic

lesions. _J Invest Dermatol_ 2003;121:1160–1162. Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar Download references AUTHOR INFORMATION AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Clinical Institute of Pathology,

Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria Ildiko Mesteri, Günther Bayer & Peter Birner * Department of Neuropathology, Institute of Pathology, Ruprecht-Karls-University Heidelberg,

Heidelberg, Germany Jochen Meyer, David Capper, Andreas von Deimling & Peter Birner * Clinical Cooperation Unit Neuropathology, German Cancer Research Centre, Heidelberg, Germany Jochen

Meyer, David Capper & Andreas von Deimling * Department of Surgery, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria Sebastian F Schoppmann Authors * Ildiko Mesteri View author publications

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Günther Bayer View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Jochen Meyer View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * David Capper View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Sebastian F

Schoppmann View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Andreas von Deimling View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar * Peter Birner View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Peter Birner. ETHICS DECLARATIONS

COMPETING INTERESTS David Capper and Andreas von Deimling declare shared investorship of VE1 antibody and have applied for a patent on its diagnostic use. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and

permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Mesteri, I., Bayer, G., Meyer, J. _et al._ Improved molecular classification of serrated lesions of the colon by immunohistochemical

detection of _BRAF V600E_. _Mod Pathol_ 27, 135–144 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.126 Download citation * Received: 08 November 2012 * Accepted: 03 June 2013 * Published: 26

July 2013 * Issue Date: January 2014 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.126 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get

shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative KEYWORDS * _BRAF_ *

colon * immunohistochemistry * morphology * serrated polyp