- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Two-component signal transduction systems (TCSs), composed of a histidine kinase sensor (HK) and its cognate response regulator, sense and respond to environmental changes and are

related to the virulence of pathogens. TCSs are potential targets for alternative antibiotics and anti-virulence agents. Here we found that waldiomycin, an angucycline antibiotic that

inhibits a growth essential HK, WalK, in Gram-positive bacteria, also inhibits several class I HKs from the Gram-negative _Escherichia coli._ NMR analyses and site-directed mutagenesis

studies using the osmo-sensing EnvZ, a prototypical HK of _E. coli_, showed that waldiomycin directly binds to both H-box and X-region, which are the two conserved regions in the

dimerization-inducing and histidine-containing phosphotransfer (DHp) domain of HKs. Waldiomycin inhibits phosphorylation of the conserved histidine in the H-box. Analysis of waldiomycin

derivatives suggests that the angucyclic ring, situated near the H-box in the waldiomycin-EnvZ DHp domain complex model, is responsible for the inhibitory activity. We demonstrate that

waldiomycin is an HK inhibitor binding to the H-box region and has the potential of inhibiting a broad spectrum of HKs. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS SYNTHESIS AND BIOCHEMICAL

CHARACTERIZATION OF NAPHTHOQUINONE DERIVATIVES TARGETING BACTERIAL HISTIDINE KINASES Article Open access 25 June 2024 SEQUESTRATION OF HISTIDINE KINASES BY NON-COGNATE RESPONSE REGULATORS

ESTABLISHES A THRESHOLD LEVEL OF STIMULATION FOR BACTERIAL TWO-COMPONENT SIGNALING Article Open access 25 July 2023 ATOMIC INSIGHTS INTO THE SIGNALING LANDSCAPE OF _E. COLI_ PHOQ HISTIDINE

KINASE FROM MOLECULAR DYNAMICS SIMULATIONS Article Open access 26 July 2024 INTRODUCTION A search for new antibacterial targets is essential to combat the increasing development of drug

resistance among bacterial pathogens. These targets are preferred to be bacteria-specific and distinct from conventional sites. Two-component signal transduction systems (TCSs) represent one

of the primary means by which bacteria sense and respond to their surrounding environment. These systems are initiated by activation of histidine kinases (HKs), which situate mostly at the

cell membrane and act as sensors of external environmental stimuli. On activation, a HK autophosphorylates its conserved histidine residue and then transfers the phosphate group to its

cognate response regulator. In turn, the phosphorylated response regulator often controls expression of genes which contributes to cellular responses against the stimuli perceived by the

HK.1 Bacterial virulence can be considered as one form of a pathogen’s adaptation to its environment and TCSs of various pathogens have been reported to be related to bacterial virulence,

drug resistance or biofilm formation. Some TCSs are even involved in cell wall synthesis, cell multiplication and division, and inhibiting such systems will hinder bacterial growth.2

Furthermore, TCSs are conserved in bacteria, averaging to more than 20 TCSs per species. Some TCSs are also found in fungi and plants, but none in mammalian cells.1 Consequently, TCS

inhibitors, especially HK inhibitors, have been searched as candidates for alternative antibiotics.2 Although TCSs are often studied and characterized individually, TCSs are assumed to form

signal transduction networks with other TCSs within the cell. Thus, inhibiting only a single system may not be sufficient to stop the bacterial response. Inhibitors that hinder multiple

signal transduction systems in a single cell could block all detours that lead to retention of virulence or survival of the bacterium.3 The catalytic regions of HKs share two highly

conserved domains, the catalytic and ATP-binding (CA) domain and the dimerization-inducing His-containing phosphotransfer (DHp) domain.4 Inhibitors against these domains will have the

potential to serve as broad-spectrum HK inhibitors. Previous studies identified several inhibitors that block the HK CA domain. Unlike other kinases, this domain possesses an ATP-binding

site, which adopts a Bergerat fold5, 6, 7 found in the GHL protein family (DNA gyrase, heat shock protein 90 and DNA mismatch repair protein MutL). Radicicol, an heat shock protein 90

inhibitor, interacts with residues in the ATP-binding pocket of a HK.6 However, binding affinity of radicicol against the HK was weak compared with that against heat shock protein 90 and,

consequently, radicicol only showed weak inhibition of HK activity. This suggested the possibility of GHL inhibitors as lead compounds for developing HK inhibitors.6 In a different study,

Qin _et al._8 conducted an _in silico_ virtual high-throughput screen using the three-dimensional structure of the CA domain of WalK, a growth-essential HK in the low G+C, Gram-positive

Firmicutes group. This screen led to the discovery of thiazolidinone derivatives that bind to the ATP-binding pocket of the WalK CA domain. However, further derivation of these compounds is

necessary to reduce their animal toxicity.8 Small compounds binding to the ATP-binding pocket have further been searched by _in vitro_ high-throughput screening or _in silico_

structure-based screening.9, 10, 11. These studies introduce new scaffolds that could serve as starting points for designing potent HK inhibitors that interact with the ATP-binding pocket.

In a different approach, inhibitors against the growth essential WalK HK were screened from natural actinobacterial extracts by a sensitive differential growth assay.12, 13, 14, 15 Among the

isolated inhibitors, signermycin B inhibited WalK activity in an ATP-noncompetitive manner. Surface plasmon resonance analyses showed that signermycin B binds to the DHp domain of WalK.14

However, the mechanism of how signermycin B inhibits the WalK activity and where in the DHp domain does this inhibitor bind remain to be elucidated. Another WalK inhibitor, waldiomycin

(Supplementary Figure S1A), was also found by the sensitive differential growth assay.15 Waldiomycin is an angucycline antibiotic composed of 1, 3-dioxolane-2-carboxylic acid linked to an

angucyclic polyketide via a tetraene linker and a tetrahydropyran. Its antibiotic activity is a result of its inhibition of WalK. Angucycline group antibiotics are known to have a wide range

of effects as antibacterial, antiviral, anti-cancer and enzyme-inhibiting agents.16 In the present study, we employed NMR spectroscopy to elucidate that waldiomycin binds to the H-box,

which comprises the autophosphorylated histidine residue and is conserved in the DHp domain of bacterial HKs. We also showed that the angucyclic polyketide moiety of waldiomycin binds

adjacent to the H-box. This is the first example of a HK inhibitor binding to the H-box region and suggests the possibility of developing angucycline-based antibiotics as signal transduction

inhibitors. MATERIALS AND METHODS HK AUTOPHOSPHORYLATION AND INHIBITION ASSAYS Purified HKs at a final concentration of 0.5 μM were used for autophosphorylation assay as described

previously.15 Inhibition of the autophosphorylation activity of HKs was evaluated by adding drugs to the autophosphorylation reaction mixture 5 min before addition of ATP, followed by

incubation at 25 °C. As for autophosphorylation of heterodimers, a mixture of 0.25 μM of EnvZ (DHp+CA) and 1 μM of EnvZ (DHp) was applied to the assay following the method essentially

identical with that for homodimeric EnvZ (DHp+CA). NMR SPECTROSCOPY The NMR titration experiments were performed using a series of 1H, 15N HSQC spectra in 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.2), 50

mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol and 10% (v/v) _d_-dimethyl sulfoxide at 288 K on a Bruker Avance II (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance

cryogenic probe operating at 700.33 MHz for the 1H resonance frequency. Samples containing up to 1.2 mM waldiomycin were titrated into 0.3 mM 15N-labeled EnvZ DHp domain (EnvZ (DHp)). Data

processing and analysis were performed with NMRPipe17 and KUJIRA18 running with NMRView19, respectively. The dissociation constant, _K_D, was estimated to fit equation (1)20 to the bound

fraction of EnvZ (DHp) dimer, _f_bound. where [_L_]total and [_P_]total are the total concentrations of waldiomycin and EnvZ (DHp) dimer, respectively, and _I_ and _I_0 are the signal

intensities with and without waldiomycin. The intensity for each signal was measured by averaging the signal intensities at the peak center and its eight surrounding points (nine-point

averaging); each peak center was found by the SPARKY ‘pc’ function (TD Goddard and DG Kneller, SPARKY 3, University of California, San Francisco). To estimate the _K_D values, we

simultaneously used the buildup profiles from the signals for G240, V241, H243, N278, E282, Q283, F284, D286 and L288 for fitting in a global fitting manner. These nine residues showed

severe signal reduction on the addition of 0.6 mM waldiomycin, ratio=_I_(0.6)/_I_0<ratioave−ratiostd, where ratioave is an average value of ratios and ratiostd is an s.d. of ratios. The

uncertainty in the dissociation constant was estimated by Monte Carlo simulations on the basis of the uncertainty of each signal intensity evaluated using the root-mean-square deviation

value on a spectral region with no signals, which was obtained by the NMRPipe built-in module. The NMR samples of the wild type and mutants of the EnvZ (DHp) contained 50 or 100 μM

15N-labeled protein in 20 mM Na-phosphate (pH 7.2), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol and 10% (v/v) _d_-dimethyl sulfoxide. All NMR spectra were acquired at 300 K using a Bruker

Avance spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance cryogenic probe operating at 500.13 MHz for the 1H resonance frequency spectrometer controlled with TopSpin 3.0 software (Bruker).

PROTEIN STRUCTURE MODELING The complex model of EnvZ (DHp) with waldiomycin was constructed from the X-ray crystal structures of free EnvZ (DHp) and waldiomycin. The initial model was

constructed by manually setting waldiomycin as the default based on the information from the intensity change of the NMR signals and mutagenesis experiments. The binding position of

waldiomycin and its interaction were adjusted through energy minimization using the Molecular Operation Environment (Chemical Computing Group, Montreal, QC, Canada) and manual fitting.

Finally, a molecular dynamics calculation was performed to remove model distortion. After the Molecular Operation Environment calculations, MMFF94x force field was selected as the default

parameter set. The structure model of NtrB (GlnL) was built through homology alignment-based structure modeling by applying the _E. coli_ NtrB amino acid sequence (gi: 948360) to the

SWISS-MODEL web server21 using the coordinates of an artificial blue-light-regulated HK, YF1 (PDB entry: 4GCZ)22 as the template. Other materials and methods including cloning, protein

expression and purification, mutant constructions, chemical cross-linking, X-ray crystallography, lists of primers and plasmids are described in Supplementary Information. RESULTS AND

DISCUSSION WALDIOMYCIN IS A GENERAL INHIBITOR OF CLASS I HKS Previously, Igarashi _et al._ showed that WalK inhibitor, waldiomycin, inhibits the autophosphorylation activity of WalK HKs

derived from four different species of Gram-positive bacteria, namely, _Bacillus subtilis_, _Staphylococcus aureus_, _Enterococcus faecalis_ and _Streptococcus mutans_.15, 23 We extend our

analysis to ask whether waldiomycin can also inhibit HKs other than WalK. HKs can be divided into two major classes based on their domain organization, class I and class II. WalK and most of

the HKs known to date are classified as class I HKs, in which the conserved phosphorylated histidine is located in the DHp domain, immediately followed by the CA domain. In class II HKs,

the phosphorylated histidine is remote from the CA domain and is located in the histidine-containing phosphotransfer domain4 (Supplementary Figure S1B). The cytoplasmic regions of HKs from

_E. coli_ and _S. mutans_ were cloned, expressed and purified, and inhibitory potency of waldiomycin was evaluated. Table 1 shows the IC50s of waldiomycin against the autophosphorylation

activity of various HKs _in vitro_. Waldiomycin inhibited 13 out of 14 class I HKs with IC50s ranging from 7.8 to 37.8 μM, suggesting that waldiomycin is a general inhibitor of class I HKs.

The only exception was NtrB, with an IC50 of 346 μM. In contrast, CheA, a class II HK, was resistant to waldiomycin with an IC50 of 555 μM. WALDIOMYCIN BINDS TO THE DHP DOMAIN The DHp and CA

domains are conserved among the class I HKs. If waldiomycin targeted the CA domain, it would most likely inhibit HKs in an ATP competitive manner, as the binding of ATP is essential to the

reaction. We examined inhibition of VicK, a WalK ortholog of _S. mutans_, in the presence of different concentrations of ATP. The IC50s of waldiomycin against VicK in the presence of 2.5 and

100 μM ATP were 45.7 and 96.2 μM, respectively, resulting to an increase of only about twofold. On the other hand, the IC50s of AMP-PNP (a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog, which inhibits HKs in

an ATP competitive manner) against VicK in the presence of 2.5 and 100 μM ATP were 7.6 and 182 μM, respectively, resulting to an increase of about 24-fold. As the IC50s of waldiomycin

against VicK in the presence of 2.5 and 100 μM ATP did not differ as much as AMP-PNP, it was suggested that waldiomycin inhibited VicK in an ATP-noncompetitive manner. Similarly, the IC50s

against EnvZ, an osmosensor HK of _E. coli_, in the presence of 2.5 and 100 μM ATP were 23.9 and 23.2 μM, respectively, whereas the IC50s of AMP-PNP against EnvZ in the presence of 2.5 and

100 μM ATP were 4.1 and 99.5 μM, respectively. Thus, waldiomycin also inhibited EnvZ in an ATP noncompetitive manner. These results suggest that waldiomycin is not preventing the binding of

ATP to the CA domain. To reveal the involvement of the DHp domain on the waldiomycin binding, we examined the effect of waldiomycin on dimerization of the cytoplasmic region of VicK,

VicK(31–450). Addition of waldiomycin to [γ-32P]-phosphorylated VicK(31–450) before the glutaraldehyde treatment (for chemical cross-linking)14 prevented the dimer cross-linking and resulted

in monomer-sized band in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, while no addition of waldiomycin mainly provided dimer-sized band (Supplementary Figure S1C, upper panel). Increasing

concentration of waldiomycin further reduced the formation of the cross-linked dimer band and the monomer band of VicK(31–450) became major at over 44.5 μM waldiomycin, suggesting that

waldiomycin masked the cross-linking sites or altered the distance between the cross-linking sites within the DHp domain. Furthermore, inhibition of the cross-linking correlated with the

inhibition of VicK(31–450) autophosphorylation (Supplementary Figure S1C, lower panel). Waldiomycin also inhibited cross-linking within EnvZ(223-450) (DHp+CA) dimers and this correlated with

the inhibition of autophosphorylation (Supplementary Figure S1D). Similar effect has been previously observed for another HK inhibitor, signermycin B, against a phosphorylated cytosolic

WalK.14 Considering that the presence of the DHp domain enables HKs to exist as homodimers, it is most likely that waldiomycin inhibited HKs by binding to the DHp domain, consistent with the

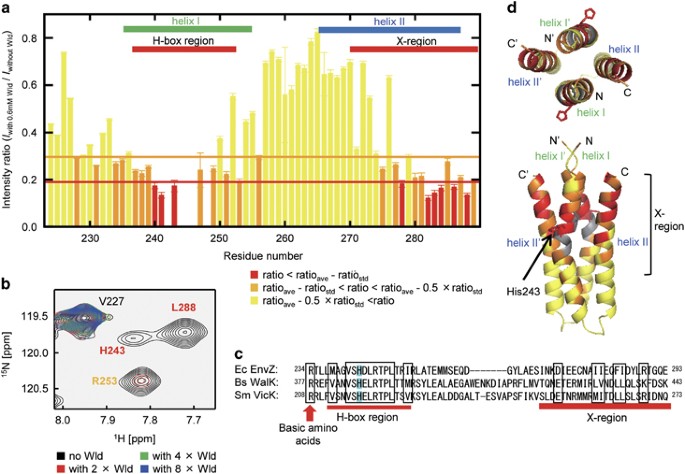

presumed binding site of signermycin B. NMR AND X-RAY CRYSTALLOGRAPHIC ANALYSES To clarify how waldiomycin binds to the DHp domain, X-ray structural analysis of EnvZ (DHp) was first carried

out, as our results showed that waldiomycin bound to EnvZ (DHp) and inhibited autophosphorylation. Despite our effort for screening, the complex structures with waldiomycin were obtained

via neither co-crystallization nor soaking method for free crystals, but the free structure of EnvZ (DHp) was determined at 1.33 Å resolution (Figure 1d, Supplementary Table S3 and

Supplementary Figure S5). The asymmetric unit of the solved structure contained a single peptide that is composed of two helices, helix I (R234-M258) and helix II (G264-L288), connected with

a five-residue short loop. Helix I contained P248 residue where the helix kinked slightly due to lacking a hydrogen bond at the main-chain amide of P248. A four-helix bundle dimer structure

was formed between two adjacent protomers that are related by crystallographic symmetry (Figure 1d). Next, we performed NMR analyses of EnvZ (DHp) in the presence of waldiomycin to

determine the binding site. 15N-labeled EnvZ (DHp) was prepared and subjected to waldiomycin titration experiments. We obtained a 1H-15N HSQC spectra of EnvZ (DHp) and assigned the chemical

shifts of the signals on the basis of the previous assignment information24 that was kindly provided by Dr M Ikura (personal communication). Increasing the amount of waldiomycin in EnvZ

(DHp) resulted in a reduction of signal intensities of specific signals in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra (Figure 1a and Supplementary Figure S2A), indicating that waldiomycin binds directly to the

specific sites of EnvZ in the slow exchange regime (Figure 1b). We did not observe any signals of waldiomycin in a bound form. The fraction of the waldiomycin-bound form of EnvZ (DHp) dimer

was calculated with the equation (1) from the signal intensity reduction of nine residues (G240, V241 and H243 in H-box; N278, E282, Q283, F284, D286 and L288 in the helix II) that were

significantly affected by adding waldiomycin. When plotted against the concentration of the EnvZ (DHp) dimer, it was found that the signal reductions were saturated when a nearly equimolar

amount of waldiomycin was added (Supplementary Figure S2I). This suggests that a single waldiomycin molecule may directly interact with an EnvZ dimer. We calculated a dissociation constant

of 4.34±0.24 μM, if assumed that a single molecule of waldiomycin binds to an EnvZ dimer. The residues that show severe signal reduction included G240-P248 in helix I and E275-R289 in helix

II at the C-terminal region (Figure 1a). The former is overlapped with the H-box (L237-I252) that is a well-known conserved motif in the DHp domain of class I HKs and includes the histidine

site (H243) of phosphorylation (Figure 1c). Closer examination with the E275-R289 of the helix II C-terminal region shows scattered, but significant homology with other class I HKs. This

region is composed of flanking charged residues and central hydrophobic residues with moderate homology, and is designated as ‘X-region’ that may be important for the hydrophobic interaction

between the helices.25 These two regions are conserved among the class I HKs used in our study (Figure 1c and Supplementary Figure S3). Further to elucidate the waldiomycin-binding site,

residues affected by the binding of waldiomycin in our NMR analyses were mapped onto the X-ray crystal structure of the EnvZ (DHp) homodimer that was generated from the monomeric coordinates

according to the crystal symmetry. As shown in Figure 1d, the affected residues of the H-box on helix I and the X-region on helix II were situated in the upper half of the homodimer. Helix

I bend at P248, creating a large cleft with helix II of the identical subunit. Most of the residues that were affected by waldiomycin binding (Figure 1d) faced this cleft. In the other

clefts between helices I’ and II or helices I and II’ (Figure 1d), the cleft-faced residues in the N-terminal half of the X-region (S269, D273 and E276) showed no significant change of

signal intensities upon waldiomycin binding (Figure 1a). These results suggest that waldiomycin binds to the cleft between helices I and II of the same subunit, but not to the clefts between

different subunits (helices I’ and II or helices I and II′). WALDIOMYCIN INHIBITS AUTOPHOSPHORYLATION BY BINDING AT THE H-BOX Twenty nine site-directed mutant proteins of EnvZ (DHp+CA) (11

mutants in the H-box, 13 in the X-region and 5 in other region) were constructed to evaluate whether the H-box, X-region and R234 in helix I of EnvZ were critical for waldiomycin inhibitory

activity. When the autophosphorylation levels of these mutants were assayed, L245A, L249A, R251A, I280A and I281A EnvZ (DHp+CA) mutants showed no or very low activity, suggesting these

residues to be essential for autophosphorylation (Supplementary Figure S4A). The other mutants such as M238A, A239D, S242A, D244A, R246A, E257A, N278A, E282A, I285A, D286A, Y287A and R289A

retained autophosphorylation activity (0.5–1.5-fold of the wild type; Supplementary Figure S4B) and were applied to inhibition assay with waldiomycin (Table 2). As a result, R234A and the

H-box mutants, S242A, D244A, T247A and P248A, were highly resistant to waldiomycin inhibition. On the other hand, all the mutants within the X-region were sensitive to waldiomycin,

suggesting that involvement of H-box and R234 of EnvZ (DHp+CA) were more important for autophosphorylation inhibition by waldiomycin. To address whether the above mentioned mutations

conferring resistance to waldiomycin affected the binding of waldiomycin to EnvZ, 15N-labeled mutant proteins of EnvZ (DHp) (S242A, D244A, T247A, P248A and R234A) were prepared and analyzed

by NMR spectroscopy with increasing amount of waldiomycin. As a control, waldiomycin titration was also performed against 15N- EnvZ (DHp) E257A. This mutation conferred neither waldiomycin

resistance (Table 2) nor inhibition of waldiomycin binding judged by the signal intensities and chemical shifts of the cross peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra (Supplementary Figure S2G). When

waldiomycin was added to the other EnvZ (DHp) mutant proteins, the cross-peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of S242A, D244A and P248A showed similar signal intensities and chemical shifts as

those without waldiomycin. These results suggest that waldiomycin did not interact with these mutant proteins (Supplementary Figures S2B,D and F) and explain why these mutations conferred

resistance against waldiomycin inhibition (Table 2). Some cross-peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of T247A showed reduction in signal intensity by the addition of waldiomycin, but the changes

were much smaller than those observed in the wild-type 15N-EnvZ (DHp) (Supplementary Figures S2A and E). This result is consistent with EnvZ (DHp+CA) T247A being less resistant to

waldiomycin inhibition than the S242A, D244A and P248A mutants (Table 2). On the other hand, EnvZ (DHp) R234A showed inconsistent results. Waldiomycin binds to EnvZ (DHp) R234A judging from

the reduction in signal intensities of specific cross-peaks (Supplementary Figure S2C), although IC50 of waldiomycin against EnvZ (DHp+CA) R234A is significantly increased (Table 2).

Furthermore, as for EnvZ (DHp) P248A, the X-ray crystal structure was determined to evaluate the structural change that arises from lack of the bending site of the helix I. The EnvZ (DHp)

P248A structure solved at 2.23 Å contained a four-helix bundle dimer (chains A and B) in the asymmetric unit (Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Figures S5B and C). The structures of

wild-type and P248A EnvZ (DHp) were compared by superimposing the main chain atoms of L249−M258 of the chain A. As shown in Supplementary Figure S5C, the entire helix I of P248A EnvZ (DHp)

extended in a nearly straight line, whereas that of the wild type kinked at P248. This result suggests that the structural change of the DHp domain, lying at its upper half (Supplementary

Figure S5C), affected the waldiomycin-binding cleft and resulted in the significant increase of IC50 for EnvZ P248A (Table 2). INHIBITORY MECHANISM OF WALDIOMYCIN Class I HKs generally

function as homodimers. ATP first binds to the CA domain on one of the subunit and transfers the phosphate to the conserved histidine residue in the H-box of the DHp domain on the same or

the other subunit. This is referred as _cis_- or _trans_-autophosphorylation.26, 27 Whether the HK functions in a _trans_ or _cis_ mode is thought to be governed by the conformation of the

loop at the base of the DHp domain, which connects helices I and II.28 EnvZ autophosphorylates only in a _trans_ manner.29 Incubating EnvZ (DHp) with EnvZ (DHp+CA) at a molar ratio of 4:1 in

the presence of [γ-32P] ATP resulted in phosphorylation of both EnvZ (DHp) and EnvZ (DHp+CA) (Supplementary Figure S6B). Phosphorylation of EnvZ (DHp) in the mixed reaction is dependent on

the heterodimer formation between EnvZ (DHp) and EnvZ (DHp+CA), because phosphorylation of EnvZ (DHp+CA) homodimer shows only a single phosphorylated band (Supplementary Figure S6A), whereas

EnvZ (DHp) homodimer is not phosphorylated (Supplementary Figure S6C). Hence, we confirmed that EnvZ (DHp) retains the ability to accept a phosphate group from the ATP bound to the CA

domain of EnvZ (DHp+CA), which is the other subunit of the heterodimer. Waldiomycin bound to the DHp domain of EnvZ (DHp+CA) may inhibit phosphorylation of the H243 of the same subunit by

masking the conserved H243 or interfering the access of the ATP-bound CA domain of the other subunit. Another possibility is that waldiomycin may block the movement of the ATP-bound CA

domain by binding adjacent to the loop connecting the DHp and CA domains, and thus inhibit phosphorylation of the H243 of the other subunit. To determine how waldiomycin inhibits HK

activity, we first examined whether waldiomycin is capable of inhibiting HK activity in the heterodimeric state. Waldiomycin was added to EnvZ (DHp) and EnvZ (DHp+CA) mixture, and assayed

for its inhibitory activity against autophosphorylation (Figure 2a). Waldiomycin inhibited the formation of phospho-EnvZ (DHp+CA) and phospho-EnvZ (DHp) with IC50s of 25.7 and 34.9 μM,

respectively. When EnvZ (DHp+CA) S242A was mixed with the wild-type EnvZ (DHp) (Figure 2b), the IC50s of waldiomycin against EnvZ (DHp+CA) S242A and EnvZ (DHp) were 2740 and 79.1 μM,

respectively. The high IC50 observed against EnvZ (DHp+CA) S242A was consistent with the results shown in Table 2 and was considered as a result from the EnvZ (DHp+CA) S242A homodimer. In

contrast, the IC50 of waldiomycin against EnvZ (DHp) showed only a slight increase compared to that for EnvZ (DHp) of the EnvZ (DHp)-EnvZ (DHp+CA) heterodimer (Figure 2a). Considering that

waldiomycin only binds to EnvZ (DHp), and not to EnvZ (DHp+CA) S242A of the heterodimer, these results indicate that the binding of waldiomycin to EnvZ (DHp) inhibits the autophosphorylation

of the conserved His residue of the same subunit. Taken together, we propose that waldiomycin inhibits class I HKs by binding to the H-box region and inhibits their autophosphorylation by

masking this region. INHIBITORY ACTIVITY OF WALDIOMYCIN DERIVATIVES To elucidate the binding mode of waldiomycin, the inhibitory activities of several waldiomycin derivatives were examined

(Table 3). A methylester derivative, in which a carboxyl group in the dioxolane ring is methyl-esterified, had similar IC50s for EnvZ (DHp+CA) wild type, R234A and S242A as those for

waldiomycin, suggesting that the negative charge of the dioxolane ring is not likely involved in binding. This observation also suggests that conserved arginine residues of EnvZ (DHp), such

as R234, R246, R251 and R289 (either occupied by arginine or lysine in class I HKs; Supplementary Figure S3), do not participate in waldiomycin binding. Dioxamycin30 is another angucyclic

antibiotic that is effective on Gram-positive bacteria and possesses a very similar chemical structure to waldiomycin, except that its angucyclic polyketide has two hydroxyl groups at the 4a

and 12b positions. Dioxamycin also inhibits the autophosphorylation activity of EnvZ (DHp+CA), with higher potency than waldiomycin (Table 3). Introduction of the R234A or S242A mutation in

EnvZ (DHp+CA) increased the IC50 of dioxamycin by 50–60-fold, an effect comparable with that for waldiomycin (30–60-fold increase in its IC50). Aquayamycin31 has the same angucyclic ring as

dioxamycin and tetrahydropyran, but lacks the tetraene linker and the dioxolane ring. Interestingly, aquayamycin exhibited a comparable inhibitory activity as waldiomycin for EnvZ (DHp+CA)

autophosphorylation. Moreover, effect of aquayamycin on Ala mutations in the H-box region (S242, D244, T247 and P248) and R234 showed significant increase in the IC50s compared with the wild

type (Table 3). If the binding mode is retained among waldiomycin, dioxamycin and aquayamycin, then the angucyclic ring of these compounds should bind close to the H-box region comprising

these residues. Rabelomycin32 is an antibiotic containing only the angucyclic ring moiety of waldiomycin and lacks the part spanning from the tetrahydropyran to the dioxolane ring. The IC50

value of rabelomycin was 14-fold higher than that of waldiomycin (Table 3). The higher IC50 values of aquayamycin and rabelomycin, compared with those of dioxamycin and waldiomycin,

suggested that the moiety from the tetrahydropyran to the dioxolane ring contributed to the binding to EnvZ. MODELING WALDIOMYCIN-ENVZ(DHP) COMPLEX On the basis of the above results,

waldiomycin was modeled on the X-ray crystal structure of EnvZ (DHp) (Figure 3). Considering that the cleft between helices I and II indicated large intensity changes in the cross peaks of

the 1H-15N HSQC spectra (Figure 1a) and the angucyclic ring of the bound waldiomycin was situated near the H-box, it is assumed that the dioxolane ring was bound to the X-region. This

initial waldiomycin-binding model was optimized by energy-minimization and further molecular dynamic simulation. Waldiomycin was bound in a position similar to the initial model and was

predicted to form several hydrogen bonds with the side chains of S242, T247, T250 and R251. Waldiomycin was fitted to the region on the cleft between helices I and II in the upper half of

the four-helix bundle (Figure 3). This is the first model of a HK inhibitor binding to the DHp domain. The dioxolane ring of waldiomycin contacts two hydrophobic residues, I285 and L288, in

the X-region (Figure 3), probably through hydrophobic interactions. In agreement with the model, these residues exhibit signal reduction in the corresponding cross peaks of the 1H-15N HSQC

spectra (Figure 1a), although the changes of IC50s of waldiomycin were minor for the Q283A, F284A, and L288A mutants (2.0, 3.5 and 1.8-fold increase, respectively, compared with the wild

type (Table 2)). In addition to the intrinsic plasticity of the hydrophobic interactions, it is considered that the mutation to Ala results in no significant change to the hydrophobicity of

the X-region. Examination of a homology model of NtrB, a class I HK with an exceptionally high IC50 (Table 1), also suggests the importance of the X-region. It is predicted in the NtrB model

that helix II of the DHp domain is short because of the inability of helix formation in the region of G187 and P188 in the X-region (Supplementary Figure S7). The model indicates that the

loop region connecting the DHp and CA domains begins from G187. Superimposition of the NtrB model with the waldiomycin-bound EnvZ model suggests that the dioxolane ring moiety is located

around G187 and P188. The absence of interactions with the dioxolane ring may account for the low affinity of waldiomycin toward NtrB. The NtrB model emphasizes the importance of the

interaction between the X-region and the dioxolane ring. Taken together, the results showed that waldiomycin is bound to the H-box and X-region of the DHp domain of EnvZ. The high and

moderate homology of the H-box and X-region, respectively, in class I HKs suggests that the DHp domain is the target of waldiomycin in other HKs, including WalK and VicK. The inhibitory

effects of the derivatives of waldiomycin and the results from the mutation experiments indicate that the interaction between the H-box and the angucyclic ring is essential for inhibition of

autophosphorylation. We conclude that waldiomycin functions as an H-box inhibitor with the potential of inhibiting a broad spectrum of HKs, suggesting the possibility of developing

angucycline-based HK inhibitors. As the orchestrated action of a number of TCSs is assumed to be involved _in situations_ when pathogens survive in the human body and cause infectious

disease, treating pathogens with broad-spectrum HK inhibitors may shut down the stress response system of bacteria, resulting in decreased viability, pathogenicity, and virulence. To date,

the ATP-binding domain has been the only target for screening such HK inhibitors.6, 8, 9, 10, 11 With our EnvZ-waldiomycin model (Figure 3), we now propose the H-box as another promising

target for obtaining broad-spectrum HK inhibitors. REFERENCES * Stock, A. M., Robinson, V. L. & Goudreau, P. N. Two-component signal transduction. _Annu. Rev. Biochem._ 69, 183–215

(2000). Article CAS Google Scholar * Gotoh, Y. _et al_. Two-component signal transduction as potential drug targets in pathogenic bacteria. _Curr. Opin. Microbiol._ 13, 232–239 (2010).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Wilke, K. E. & Calson, E. E. All signals lost. _Sci. Transl. Med._ 5, 203ps12 (2013). Article Google Scholar * Tomomori, C., Kurokawa, H. & Ikura,

M. in _Histidine Kinases in Signal Transduction_ (eds Inouye, M. & Dutta, R. 11–24 Academic Press, San Diego, CA, USA, (2003). Book Google Scholar * Dutta, R. & Inouye, M. GHKL, an

emergent ATPase/kinase superfamily. _Trends Biochem. Sci._ 25, 24–28 (2000). Article CAS Google Scholar * Guarnieri, M. T., Zhang, L., Shen, J. & Zhao, R. The Hsp90 inhibitor

radicicol interacts with the ATP-binding pocket of bacterial sensor kinase PhoQ. _J. Mol. Biol._ 379, 82–93 (2008). Article CAS Google Scholar * Tanaka, T. _et al_. NMR structure of the

histidine kinase domain of the _E. coli_ osmosensor EnvZ. _Nature_ 396, 88–92 (1998). Article CAS Google Scholar * Qin, Z. _et al_. Structure-based discovery of inhibitors of the YycG

histidine kinase: new chemical leads to combat _Staphylococcus epidermidis_ infections. _BMC Microbiol._ 6, 96 (2006). Article Google Scholar * Cai, X. _et al_. The effect of the potential

PhoQ histidine kinase inhibitors on _Shigella flexneri_ virulence. _PLoS ONE_ 6, e23100 (2011). Article CAS Google Scholar * Wilke, K. E., Francis, S. & Carlson, E. E. Inactivation

of multiple bacterial histidine kinases by targeting the ATP-binding domain. _ACS Chem. Biol._ 10, 328–335 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Velikova, N. _et al_. Putative histidine

kinase inhibitors with antibacterial effect against multi-drug resistant clinical isolates identified by _in vitro_ and _in silico_ screens. _Sci. Rep._ 6, 26085 (2016). Article CAS Google

Scholar * Okada, A. _et al_. Targeting two-component signal transduction: a novel drug discovery system. _Methods Enzymol._ 422, 386–395 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Okada, A.

_et al_. Walkmycin B targets WalK (YycG), a histidine kinase essential for bacterial cell growth. _J. Antibiot. (Tokyo)_ 63, 89–94 (2010). Article CAS Google Scholar * Watanabe, T. _et

al_. Isolation and characterization of signermycin B, an antibiotic that targets the dimerization domain of histidine kinase WalK. _Antimicrob. Agents Chemother._ 56, 3657–3663 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Igarashi, M. _et al_. Waldiomycin, a novel WalK-histidine kinase inhibitor from _Streptomyces_ sp MK844-mF10. _J. Antibiot. (Tokyo)_ 66, 459–464 (2013).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Rohr, J. & Thiericke, R. Angucycline group antibiotics. _Nat. Prod. Rep._ 9, 103–137 (1992). Article CAS Google Scholar * Delaglio, F. _et al_.

NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. _J. Biolmol. NMR_ 6, 277–293 (1995). Article CAS Google Scholar * Kobayashi, N. _et al_. KUJIRA, a package of

integrated modules for systematic and interactive analysis of NMR data directed to high-throughput NMR structure studies. _J. Biolmol. NMR_ 39, 31–52 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar *

Johnson, B. A. Using NMRView to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules. _Methods Mol. Biol._ 278, 313–352 (2004). CAS PubMed Google Scholar * Fielding, L. NMR methods for

the determination of protein-ligand dissociation constants. _Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc._ 51, 219–242 (2007). Article CAS Google Scholar * Biasini, M. _et al_. SWISS-MODEL:

modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. _Nucleic Acids Res._ 42, W252–W258 (2014). Article CAS Google Scholar * Diensthuber, R. P., Bommer, M.,

Gleichmann, T. & Möglich, A. Full-length structure of a sensor histidine kinase pinpoints coaxial coiled coils as signal transducers and modulators. _Structure_ 21, 1127–1136 (2013).

Article CAS Google Scholar * Fakhruzzaman, M. _et al_. Study on _in vivo_ effects of bacterial histidine kinase inhibitor, Waldiomycin, in _Bacillus subtilis_ and _Staphylococcus aureus_.

_J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol._ 61, 177–184 (2015). Article CAS Google Scholar * Tomomori, C. _et al_. Solution structure of the homodimeric core domain of _Escherichia coli_ histidine kinase

EnvZ. _Nat. Struct. Biol._ 6, 729–734 (1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Hsing, W., Russo, F. D., Bernd, K. K. & Silhavy, T. J. Mutation that alter the kinase and phosphatase

activities of the two-component sensor EnvZ. _J. Bacteriol._ 180, 4538–4546 (1998). CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Dutta, R., Qin, L. & Inouye, M. Histidine kinases:

diversity of domain organization. _Mol. Microbiol._ 34, 633–640 (1999). Article CAS Google Scholar * Casino, P., Rubio, V. & Marina, A. Structural insight into partner specificity and

phosphoryl transfer in two-component signal transduction. _Cell_ 139, 325–336 (2009). Article CAS Google Scholar * Ashenberg, O., Keating, A. E. & Laub, M. T. Helix bundle loops

determine whether histidine kinases autophosphorylate in cis or trans. _J. Mol. Biol._ 425, 1198–1209 (2013). Article CAS Google Scholar * Yang, Y. & Inouye, M. Intermolecular

complementation between two defective mutant signal-transducing receptors of _Escherichia coli_. _Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA_ 88, 11057–11209 (1991). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sawa, R.

_et al_. Dioxamycin, a new benz[a]anthraquinone antibiotic. _J. Antibiot. (Tokyo)_ 44, 396–402 (1991). Article CAS Google Scholar * Sezaki, M., Hara, T., Ayukawa, S., Takeuchi, T. &

Okami, Y. Studies on a new antibiotic pigment, aquayamycin. _J. Antibiot. (Tokyo)_ 21, 91–97 (1968). Article CAS Google Scholar * Liu, W. C. _et al_. Isolation, characterization, and

structure of rabelomycin, a new antibiotic. _J. Antibiot. (Tokyo)_ 23, 437–441 (1970). Article CAS Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank Dr Kiong Ho (University of

Tsukuba) for the critical reading and valuable comments to the manuscript and Dr Mitsuhiko Ikura (University of Toronto) for kindly providing the signal assignment information of EnvZ (DHp).

This work was supported by the Research and Development Program for New BioIndustry, Initiatives (2006-2010) of the Bio-Oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution (BRAIN), Japan

(to RU), MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research foundation at Private Universities, 2011-2015 (S1101035) (to RU), Platform for Dynamic Approaches to Living System (to NT) and

funding from the Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices (to TO). This work was performed using the synchrotron beamline station BL44XU at SPring-8 under the Cooperative

Research Program of the Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University (Proposal Numbers: 2010A6511, 2010B6511, 2011A6610, 2011B6610, 2012A6710, 2013A6810, 2013B6810, 2014A6912, 2014B6912

and 2015A6508). AUTHOR INFORMATION Author notes * Yoko Eguchi, Toshihide Okajima and Naoya Tochio: These authors contributed equally to this work. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Department of

Bioscience, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kindai University, Nara, Japan Yoko Eguchi, Yoichi Inukai, Riko Shimizu, Shuhei Ueda, Shoko Shinya, Tamo Fukamizo & Ryutaro Utsumi *

Department of Science and Technology on Food Safety, Kindai University, Kinokawa, Japan Yoko Eguchi * Institute of Scientific and Industrial Research, Osaka University, Ibaraki, Japan

Toshihide Okajima * Department of Chemistry, Osaka Medical College, Takatsuki, Japan Toshihide Okajima * Research Center for the Mathematics on Chromatin Live Dynamics, Graduate School of

Science, Hiroshima University, Higashi-Hiroshima, Japan Naoya Tochio * RIKEN Systems and Structural Biology Center, Yokohama, Japan Naoya Tochio & Takanori Kigawa * Institute of

Microbial Chemistry (BIKAKEN), Tokyo, Japan Masayuki Igarashi Authors * Yoko Eguchi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Toshihide Okajima

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Naoya Tochio View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar *

Yoichi Inukai View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Riko Shimizu View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * Shuhei Ueda View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Shoko Shinya View author publications You can also search for this author

inPubMed Google Scholar * Takanori Kigawa View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Tamo Fukamizo View author publications You can also search

for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Masayuki Igarashi View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * Ryutaro Utsumi View author publications You

can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to Ryutaro Utsumi. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no conflict of

interest. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The Journal of Antibiotics website SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION (PDF 1582 KB)

RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Eguchi, Y., Okajima, T., Tochio, N. _et al._ Angucycline antibiotic waldiomycin recognizes common

structural motif conserved in bacterial histidine kinases. _J Antibiot_ 70, 251–258 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ja.2016.151 Download citation * Received: 01 September 2016 * Revised: 29

September 2016 * Accepted: 21 November 2016 * Published: 21 December 2016 * Issue Date: March 2017 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ja.2016.151 SHARE THIS ARTICLE Anyone you share the

following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard Provided by the Springer

Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative