- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

ABSTRACT Ancient DNA (aDNA) provides direct evidence of historical events that have modeled the genome of modern individuals. In livestock, resolving the differences between the effects of

initial domestication and of subsequent modern breeding is not straight forward without aDNA data. Here, we have obtained shotgun genome sequence data from a sixteenth century pig from

Northeastern Spain (Montsoriu castle), the ancient pig was obtained from an extremely well-preserved and diverse assemblage. In addition, we provide the sequence of three new modern genomes

from an Iberian pig, Spanish wild boar and a Guatemalan Creole pig. Comparison with both mitochondrial and autosomal genome data shows that the ancient pig is closely related to extant

Iberian pigs and to European wild boar. Although the ancient sample was clearly domestic, admixture with wild boar also occurred, according to the D-statistics. The close relationship

between Iberian, European wild boar and the ancient pig confirms that Asian introgression in modern Iberian pigs has not existed or has been negligible. In contrast, the Guatemalan Creole

pig clusters apart from the Iberian pig genome, likely due to introgression from international breeds. SIMILAR CONTENT BEING VIEWED BY OTHERS WHOLE GENOME SEQUENCE ANALYSIS REVEALS GENETIC

STRUCTURE AND X-CHROMOSOME HAPLOTYPE STRUCTURE IN INDIGENOUS CHINESE PIGS Article Open access 10 June 2020 COMPLETE MITOCHONDRIAL GENOME SEQUENCE ANALYSIS REVEALED DOUBLE MATRILINEAL

COMPONENTS IN INDIAN GHOONGROO PIGS Article Open access 17 January 2025 THE 1000 CHINESE INDIGENOUS PIG GENOMES PROJECT PROVIDES INSIGHTS INTO THE GENOMIC ARCHITECTURE OF PIGS Article Open

access 22 November 2024 INTRODUCTION Ancient DNA (aDNA) is a powerful tool to unravel the complex history of domestic species (Larson et al., 2007; Krause-Kyora et al., 2013; Ottoni et al.,

2013; Thalmann et al., 2013). Most aDNA studies in livestock have focused on very early events, such as domestication, and have provided very limited evidence based primarily on a single

locus-like mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Although mtDNA is useful for phylogeographic analyses due to its high substitution rate, using a single locus that only reflects the matrilineal history

does not help in resolving the complete demographical or selective history of a population. Artificial selection, via the processes of breeding, has dramatically sculpted livestock genome

diversity in a very short time frame. The history of livestock breeds comprises vivid examples of accelerated evolution. The largest selection intensities for livestock have been exerted

only since the last century, whereas domestication was a process that preceded such events by many more centuries. Disentangling the effects of domestication from those of modern breeding on

the genome by simply comparing wild and domestic specimens (say wild boar vs pig) is difficult because domestics carry signatures of modern breeding and selection. To that end, the

sequencing of ancient domestic genomes predating the advent of breeds and modern artificial selection era is unavoidable. Fortunately, paleopopulation genetics has become feasible with the

advent of new sequencing technologies (Wall and Slatkin, 2012). In the case of pigs, our knowledge of ancient genomes is currently limited to short mtDNA sequences (Larson et al., 2007;

Meiri et al., 2013) and a fragment of the _MC1R_ gene (Krause-Kyora et al., 2013), which is involved in coat color determination. Despite this limited evidence, the history of the pig is

unfolding to be much more complex than anticipated. Although the domestication of the pig in the Near East at least by 8500 BC is well documented (Conolly et al., 2011), recent

investigations have shown that early domestic pigs in Europe carried a distinctive NE mitochondrial lineage, which was gradually replaced by a local European wild boar signature (Larson et

al., 2007; Manunza et al., 2013; Ottoni et al., 2013). Pig meat was a key component in the neolithic diet and it was kept continuously throughout prehistory, with different management

strategies. It was during Roman times when pig farming, throughout the whole of Western Europe, underwent one of the most significant transitions. Several ancient texts on stock-breeding

published by Latin authors (Cato, Varro, Columella and Palladius) advised on the practise of selective breeding as a way to contribute to increasing the productivity of the species

(MacKinnon, 2004). During the late medieval and early modern era, another key turning point in pig breeding occurred. Archeo-zoological analyses of faunal assemblages dated to this time

highlight important changes in the health and size of domestic pigs. These changes are thought to be the product of new farming strategies and selection criteria (Albarella, 1997; Thomas,

2005; Albarella et al., 2009). In this sense, one of the aspects that has most often been emphasized is a change from a system of extensive farming to rearing in confinement (Ervynck et al.,

2007), allowing for a more intensive control of the animals and their nutrition (Thomas et al., 2013). This system would have directly influenced the speed of the development after birth

(Albarella, 1997). At the same time, keeping the animals permanently in stables isolated the domestic population from wild animals, thus decreasing the possibilities of hybridization and

gene flow between populations (Albarella et al., 2009). The sixteenth century was an important milestone for pig history. In addition to changes in breeding practices mentioned, it predates

the introgression of Asian germplasm that occurred from the seventeenth century onwards, when porcine colonization of the Americas was beginning in earnest, and three centuries before the

creation of modern breeds and of ensuing intense selection for growth and leanness that continues today. Therefore, pigs from this period would represent the original European genome and can

serve as a yardstick against which to compare selective and introgression events that were to happen later in time. It is also of particular interest to ascertain whether extant modern

Iberian pigs are representative of past porcine populations, because these local mediterranean pigs are thought not to be introgressed with Chinese pigs (Alves et al., 2003). This will be of

utmost importance to identify the Asian footprints in European pigs and its relationship with selective events. Also of historical interest is to characterize the genetic legacy of the

ancient pig in modern American Creole (village) pigs. Although Creole pigs have been thought to be direct descendants of sixteenth century Iberian pigs, its actual history is seemingly much

more complex (Burgos-Paz et al., 2013). To understand better these issues, we present here the partial genome sequence of a sixteenth century pig from the Montsoriu castle in North East

Spain (province of _Girona_). Montsoriu castle is, at present, one of the most representative examples of social and economic organization in medieval and early modern times (tenth–sixteenth

centuries). The continuous and large archeological sequence allows for the dynamics and changes in livestock husbandry from the tenth to the sixteenth century to be traced back. This is one

of the few examples where it is possible to assess the evolution of pig breeding practices and their impact on the species (Font et al., 2010). Pig remains could therefore be representative

of the general improvements in agronomic techniques and the application of new selective pressures during late middle ages (Ervynck et al., 2007). In addition to the ancient pig, we also

sequenced three new genomes pertaining to a wild boar from the same Spanish region, an Iberian pig from the highly inbred strain Guadyerbas (Toro et al., 2008) and an American Creole pig

from Guatemala. These modern samples provide evidence on important historical and genetic events like domestication, admixture and the relationship with Creole pigs. MATERIALS AND METHODS

ARCHEOLOGICAL SAMPLING AND CONTEXT Montsoriu castle is located in the province of _Girona_, in the North East of the Iberian Peninsula (41°46′58′′N, 2°32′30′′E, at 630 m.a.s.l). During the

2007 season, an abandoned cistern was excavated. It corresponds to the last stable occupation phase at the castle, and it yielded an extremely well-preserved assemblage (UE 10955). This

sample results from a specific action carried out in a very short time, a fact that ensures its integrity in chronological, analytical and explanatory terms. Taphonomic analyses demonstrate

that the bones buried quickly, which inhibited deterioration. The integration of archeological and historical (coinage date of associated coins; pottery production date, morphology,

decoration) sources evidence that the assemblage recovered was produced mainly between 1520 and 1550, and deposited at the latest in 1570. This assemblage is a unique, very varied and

complete finding, and provides a full panorama of daily life in a castle in Renaissance time (Font et al., 2007, 2008, 2010). A total of 1729 pig remains were retrieved from UE10955. The

slaughtering patterns reveal that the specimens, mostly males, were systematically consumed toward the end of their growth stage (88%), mainly between 12 and 18 months of age (40%). Some

adult females are also present and these would have been slaughtered at the end of their breeding life. Interestingly, osteometric analyses have shown that the remains of this species

correspond to animals larger than those recorded in earlier centuries at the same site. The sample selected for sequencing was a tibia (diaphysis and distal epiphyses) of an adult without

any apparent pathology and aged over 3.5 years. Age was estimated according to fusion stage (Silver, 1969). Bone surface characteristics demonstrate that the bone buried quickly, which

inhibited weathering and deterioration. Measurements, taken according to Von Den Driesch (1976), were s.d.=19.5/Bd=28.8/Dd=25.5 and ensure that the bone corresponds to a domestic animal.

MODERN SAMPLES Two modern pig data sets were used to compare the ancient genome with worldwide samples. The first one (Supplementary Table S1) consisted of two biodiversity panels that were

genotyped with the 60k Illumina’s SNP array. The first panel is a wide sample (_n_=379) of international, Chinese and American Creole breeds, together with European and Tunisian wild boar

(Burgos-Paz et al., 2013), and the second panel (_n_=40) comprised NE wild boars (Turkey, Iran and Armenia) and Romanian Mangalitza, a central European local pig (Manunza et al., 2013).

These data were combined with the genotypes inferred from sequence in the ancient pig, as detailed below. The second data set (Supplementary Table S2) consisted of eight modern genomes,

whose sequences were publicly available or were shotgun sequenced for this study. Specifically, we re-sequenced a wild boar from the same area of NE Spain (WB), an Iberian pig (IB) from the

highly inbred strain Guadyerbas (Toro et al., 2008), and an American Creole pig (CR) from Guatemala. In addition, we used one publicly available genome from each of Duroc (DU), Landrace

(LR), Large White (LW), Hampshire (HS) and Pietrain (PI) breeds. These samples represent all main modern international pig breeds together with potentially closest extant relatives. DNA

EXTRACTION AND SEQUENCING DNA extractions of the ancient and modern samples were performed at different times and in different laboratories. All experimental procedures on ancient samples

were performed in a dedicated aDNA laboratory (IBE-PRBB, Barcelona, Spain), where no previous work with modern pigs had been conducted. DNA extraction was performed for each of the three

best preserved ancient pig samples. DNA was isolated by a conventional phenol–chloroform precipitation protocol and microcolumn concentration (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), as described

elsewhere (Lalueza-Fox et al., 2007; Sánchez-Quinto et al., 2012). The extract was purified with a gene clean silica method using a DNA extraction Kit (Fermentas, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Following extraction we amplified and sequenced a 77 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome _b_ (_MT_ _-CYB_) gene to test the quality of the samples. Amplification was performed using

a two-step PCR protocol (Krause et al., 2006). Amplified products were purified with a gene clean silica method (Fermentas) and cloned using the Topo TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, De Schelp,

The Netherlands). White colonies were subjected to 30 cycles of PCR with M13 universal primers and subsequently sequenced with an Applied BioSystems 3100 DNA sequencer (Foster City, CA,

USA), at the sequencing service of the _Universitat Pompeu Fabra_ (Barcelona, Spain). The partial sequence of the _MT-CYB_ gene was obtained from two of the three samples. Of these two

samples we selected the individual that, according to bone size, was the most likely domestic specimen. Ancient and modern samples were sequenced in different institutions to avoid

contamination as much as possible. From the ancient individual DNA, three single-end lanes of 100-bp length reads were sequenced at Fasteris (www.fasteris.com, Plan-les-Ouates, Switzerland)

using HiSeq2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The library was prepared with the TruSeq DNA sample preparation kit from Illumina following the instructions of the manufacturer. Modern

samples were sequenced in _Centro Nacional de Análisis Genómico_ (CNAG, www.cnag.cat) also using HiSeq2000 Illumina platform. The library preparation of each modern sample was performed

according to the Illumina paired-end sequencing protocol with minor modifications. ANCIENT DATA ALIGNMENT AND QUALITY CONTROL To process raw ancient data, we first removed stretches of N′s

and stretches of consecutive bases with 0, 1 or 2 quality scores from the 3' and 5' ends of the reads. Reads shorter than 30 nucleotides were discarded for further analyses, a

common practice in aDNA studies to minimize the risk of erroneous alignments (Rasmussen et al., 2011, 2014; Olalde et al., 2014). Post-mortem degradation results in a short length of aDNA

sequences. As a result, adapter sequences ligated during library preparation can be present at the end of the reads. This can affect the correct mapping to the reference genome and it can

also bias the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling. Therefore, we used adapter removal (Lindgreen, 2012) to remove adapter sequences from the reads, discarding sequences shorter than

30 bp after adapter trimming. We found 13% of the reads containing adapter sequence, keeping a total of 408 912 560 reads with an average length of 93 bp, which were aligned to the pig

reference genome. We mapped reads to the current pig genome assembly (Sscrofa10.2) using BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009) with the quality trimming parameter set to a Sanger quality score of 15.

Furthermore, to improve the aDNA read mapping against modern reference genomes the edit distance parameter was set to 0.02, and the seed region (the first 32 nucleotides) was disabled

following recommendations in Schubert et al. (2012). Finally, we removed duplicates with SAMtools rmdup option. In order to assess the level of human contamination, we mapped all the reads

to the human reference assembly (GRCh37/hg19) using BWA. A metagenomic analysis and taxonomic classification of one million of around 133 millions reads non-mapping to the _Sus scrofa_

assembly was performed using BLAST 2.2.27+ and MEGAN4 (Huson et al., 2011). In order to assess whether we were infra-representing taxonomy diversity by down sampling to one million reads, we

performed rarefaction curves by counting the number of detected leaves by cumulatively increasing the number of reads in bins up to the total of reads assigned at the level of genus. We

observed that the curve approached a plateau with poor increase of new genus discovered when the last bins of our subset were analyzed. Also, we specifically assessed the presence of

integrated or episomal viral DNA in the ancient pig sample. We mapped, using BWA-0.7.4 mem, all reads non-mapping to the reference _Sus scrofa_ genome against a sequence database including

all known genomes of DNA viruses. Mapping reads were then mapped again against individualized viral genomes using BWA-0.7.4 aln and we counted the number of uniquely mapping reads. For

allele determination in the ancient sample, we considered only reads with minimum mapping quality of 20, and base quality (Phred score) of at least 30 if there was a single read covering

that position or 20 with depths 2–5 × . Positions covered with >5 × were discarded, as being most likely caused by repetitive or copy number variant regions. To avoid post-mortem DNA

damages that lead to increased C→T and G→A transitions, we only retained those positions where the ancient allele was also observed in any of the eight modern pig genomes used for this study

(Supplementary Table S2). This filtering should decrease dramatically the number of post-mortem changes accepted as true variants by a factor of at least ∼1/2 a16θ. This is the probability

of finding a base in the eight modern samples that coincide with a given post-mortem damage. Suppose that the ancient sample has a post-mortem modification at a given (unknown) site; what is

the probability that this change is also observed in any of the modern samples and therefore taken as a true variant? This is the probability of observing a variant in any of the modern

samples (_a_16_θ_) times the probability that any of the two alleles coincide with any of the two nucleotides in the ancient sample (1/2), with _a_16_θ_ being the expected number of

polymorphisms per nucleotide to be found in eight diploid samples or 16 chromosomes, _a__n_ being Ewens’ constant (_a_16=3.4) and _θ_ the variability per site (or ∼0.002 in pigs), the

constant 1/2 occurs because half of the potential errors will be accepted, when they match any of the two alleles found in the modern population. In practice, this is an upper limit because

post-mortem changes occur randomly in each DNA fragment and, for depths >1, this requires that the same post-mortem change has occurred in all fragments sequenced. An assumption here is

that all samples sequenced originate from the same population (a neutral model is implicitly assumed); however, except for extreme selective events that are specific of the ancient sample,

this assumption should have only a minor effect. Admittedly, this filtering will also remove true variants that are observed only in the ancient sample. These will tend to be variants at low

frequency in the whole pig population; otherwise, it is likely that they are observed in any of the modern samples as well. The expected percentage of polymorphisms, that are singletons in

the ancient sample and are therefore discarded even if being true variants, is also obtained from Ewen’s sampling term. Assuming a standard neutral model, this corresponds 1−_a_16/_a_17∼2%;

this follows from the fact that we ascertain 16 modern chromosomes but only one ancient allele; and therefore we expect to observe _a_16 SNPs within modern samples, and _a_17 including the

ancient sample. In all, the bias due to removing singletons is expected to be small. This reasoning discards the possibility that the ancient sample is homozygous for a variant not observed

in any of the modern samples. This event is, however, highly unlikely because shallow coverage prevents confidently observing both alleles for most of sites in the diploid ancient genome.

MODERN DATA ALIGNMENT AND GENOTYPE CALLING Modern sample (Supplementary Table S2) reads were aligned with BWA (Li and Durbin, 2009) allowing for seven mismatches. Genotypes were called using

the SAMtools mpileup option and filtered with vcfutils.pl varFilter, all modern samples were analyzed together setting a minimum depth to 5 × and a maximum depth of twice the average

sample’s depth plus one, minimum map quality of 20 and minimum base quality of 20. Setting a maximum depth was done to minimize risks of wrongly called SNPs caused by copy number variants or

repetitive regions, as in Groenen et al. (2012) or Esteve-Codina et al. (2013). The resulting vcf file was merged with the ancient reads. For further analyses, we retained only the

positions without missing data in any of the samples and where the ancient reads were compatible with the modern sample genotypes. Genotypes were stored and managed as plink (Purcell et al.,

2007) files, using custom perl and shell scripts as needed. MITOCHONDRIAL ANALYSIS Complete mitochondrial sequences were downloaded from GenBank (accessions AF486866, EU117375, FJ236991,

FJ236992, FJ236993, FJ236994, FJ236995, FJ236996, FJ236997, FJ236998, FJ236999, FJ237000, FJ237003, NC_012095). In addition, aligned bam files were obtained for project ERP001813 (GenBank

accession, Groenen et al., 2012), from Wuzhishan Chinese mini pig (Fang et al., 2012; AJKK00000000) and from Iberian genome (Esteve-Codina et al., 2013; SRX245748); mtDNA consensus sequences

were obtained from these complete genomes and from the modern samples sequenced here using SAMtools (Li et al., 2009). All sequences were aligned with MUSCLE v3.8.31 (Edgar, 2004) using

options diags and maxiters 2. A median-joining network was constructed with Network 4.6 (Bandelt et al., 2000) and a neighbor-joining tree was obtained with Mega 5.1 (Tamura et al., 2011)

using pairwise deletion, maximum composite likelihood and homogeneous rates model. ARRAY GENOTYPING ANALYSES Only positions in the ancient individual bam file with enough quality and only

alleles compatible with modern sample 60k array genotypes were retained. Given that SNP allele coding in the array does not directly correspond to actual sequenced bases, we employed the

following procedure: * 1 SNP alleles were coded from forward to TOP/BOTTOM using GenGen pipeline (Wang et al., 2007). * 2 We identified the set of chip SNP positions that were represented in

the ancient sequence, filtered by quality criteria described (map quality⩾20, base quality⩾30 if depth 1, BQ⩾20 if depth 2–5). * 3 We checked, in several modern pigs that were genotyped

with the 60k chip and sequenced, the actual polymorphisms found at those positions. We considered only those SNPs with at least two copies per allele. * 4 Monomorphic and triallelic SNPs

were discarded. * 5 In addition, for every SNP, we verified the strand orientation and allele with the probe flanking regions provided by the International Pig Sequencing Consortium during

the development of the Illumina’s array. * 6 Allele coding was verified with several public data sets of our own Burgos-Paz et al. (2013), Badke and Steibel

(https://www.msu.edu/~steibelj/JP_files/SNP_chip.html) and from M Groenen _et al._ (personal communication). * 7 We discarded SNPs where the ancient allele did not match any of the two

modern sample alleles. We performed principal component analysis with prcomp R package (R Development Core Team, 2011). Given that only one ancient allele can be recovered for most of

positions, we duplicated the ancient allele to build a homozygous genotype. This is equivalent to oversampling to reduce bias in PC, which is very sensitive to unequal sampling (McVean,

2009). To verify the robustness of this procedure, we also sampled one random allele from each SNP in the modern samples. A few of these plots are shown for comparison. To visualize

relationships across populations, we computed the average Euclidean distances between all pairs of individuals from two different populations using the first 4 principal components, those

explaining most of variability. Suppose individual _i_ has principal component value PCik for component _k_. The Euclidean distance with the first Q components is . As in Burgos-Paz et al.

(2013), we ran a partially supervised admixture (Alexander et al., 2009) analysis using _K_=7 clusters corresponding to origins Iberian, wild boar, Duroc, Landrace, Large White, Chinese

breeds and Hampshire. Pig origins from those breeds were assumed to be known without error, whereas those of the remaining individuals were inferred from these _K_=7 ‘pure’ origins. PAIRWISE

ALLELE DIFFERENCES If only one allele of a genotype is ascertained, precise allele differences with a diploid genotype cannot be measured. They can nevertheless be bounded between maximum

and minimum values, or weighted assuming Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and allele frequency of A as _f_: In practice, all three distances are highly correlated. Unless otherwise stated, here we

employed the weighted measures because they were directly comparable with differences obtained between two diploid genotypes from modern samples. GENOME SEQUENCE ANALYSES As for the 60k

array analyses, we retained bases of the ancient pig only if they were found in any of the eight modern samples, as described above. Further, we retained only the biallelic variable

positions without missing data in any of the samples. Principal component analysis was performed with sequence genotypes as described. We investigated the likelihood that the ancient sample

was actually domestic (and not wild boar) using the diagnostic SNPs in Rubin et al. (2012) and their Supplementary Table S3. These are SNPs with extreme frequencies between wild boar and

domestics. For those SNPs, we extracted genotypes in the ancient pig sequence, from four sequenced individuals of several breeds and European wild boar (Groenen et al., 2012), and we

computed allele frequencies per breed. In the ancient pig, only one allele can be ascertained so frequencies were 0 or 1. Suppose _f_D and _f_W are, respectively, allele frequencies in

domestic and wild boar as reported by Rubin et al. (2012) and _f_S is the frequency obtained in our sample; we computed _p_D=_f_D_f_S+(1−_f_D)(1−_f_S) and _p_W=_f_W_f_S+(1−_f_W)(1−_f_S), the

probabilities of a ‘domestic’ or ‘wild’ allele being equal to the sample allele as an assignment probability to the sample being domestic or wild boar. Standard errors were computed with

bootstrap using library boot from R package (R Core Team, 2014). To test for admixture between a sample and wild boar, we calculated the D-statistics and their corresponding normalized

values (z-scores) using ADMIXtools’ qpDstat (Patterson et al., 2012). This statistic was first used by Green et al. (2010) to detect admixture between human and Neanderthal genomes, and is

very powerful to detect admixture between ancient populations, even if they are closely related. To compute the z-score, jackknife was used as recommended by the authors, with the number of

blocks set to 496. This statistic provides information about the direction of the gene flow. Having four populations W, X, Y and Z, if z-score is positive then the gene flow occurred between

either W and Y or X and Z; if negative, either between X and Y or W and Z. We considered different quartets containing the ancient, Iberian, Hampshire, European wild boar and a Sumatran

wild boar (accession ERX149139) as outgroup. As for European wild boars, we used the Spanish wild boar sequenced here and, for comparison, two publicly available WB genomes from France

(accession ERX149180) and Switzerland (accession ERX149181). RESULTS ANCIENT SEQUENCING AND QUALITY CONTROL Main mapping statistics are in Supplementary Table S3. Out of three single read

lanes on HiSeq2000, a total of 414 198 109 reads of 101 nucleotides were generated. After trimming, filtering and removing duplicates (see Materials and methods), 3 594 543 aligned reads

were retained. This is equivalent to a shotgun efficiency of 0.88%, similar to those reported in other ancient samples from the Iberian Peninsula (García-Garcerà et al., 2011; Sánchez-Quinto

et al., 2012). When the alignment was carried out against the human genome, 60 488 reads were mapped, indicating that human contamination was ∼0.34%, also in concordance on bone material

handled by archeologists (Ramírez et al., 2009a; García-Garcerà et al., 2011). Nevertheless, only 1.68% of the reads that mapped in the pig genome also mapped in human (Supplementary Figure

S1). These reads are likely to originate from highly conserved regions, and therefore expected to show low levels of variability. Given that our analyses considered only SNPs also present in

the pig modern samples and the implausibility of the same SNP appearing in two distant lineages, it is unlikely that human contamination affects the results reported here. Around 93% of all

reads did not match any subject in nr database (Supplementary Figure S2). Of the ∼7% of aligned reads, ∼93% corresponded to bacterial organisms, 6.7% to Eukaryota and <1% to Archea

(Supplementary Figure S2). Microbials present in the ancient pig sample were mostly terrestrial, rod- or filament-shaped, mesophilic at temperature and aerobic organisms with unknown

involvement in disease. These results are similar to those obtained from an ancient sample of the Iberian Peninsula (Olalde et al., 2014). We also analyzed individually the presence of all

known DNA viruses and only found PhiX (7156 uniquely mapping reads) used by Illumina as lane control. Although the DNA from the ancient sample was extracted in a dedicated aDNA laboratory

(IBE-PRBB, Barcelona, Spain), where no previous work on pigs had been carried, there is still a small probability of contamination with other pig samples. We calibrated the possibility of

this event by checking for heterozygote positions in the mitochondrial sequence. We obtained a low depth-of-coverage (2.4 × ) in the ancient mtDNA genome and we found 41 heterozygote

positions; 21 (51%) of these were C/T or G/A changes that are likely attributable to post-mortem damage. To determine whether the rest of heterozygote sites could be due to contamination

from other pigs, and not to sequencing errors, we analyzed if these position are polymorphic in the panel of 41 complete mtDNA sequences used in this study. Only 6 out of 20 heterozygous

positions were also segregating in at least one modern complete mtDNA sequence. The same analysis in a low depth-of-coverage mtDNA genome (1.9 × ) from a modern pig (Duroc) rendered very

similar results, 37 heterozygote positions and 6 of these segregating in the panel of the 41 complete mtDNA. In all, it seems that contamination from other porcine samples is unlikely to

bias the results presented here. After alignment, 9% of the _Sus scrofa_ 10.2 assembly was covered with average depth of 2 × (equivalent to a genome-wide average depth ∼0.11 × ); the

percentage of genome aligned was uniform across chromosomes except sex chromosome X (Supplementary Figure S3). The pig sequenced was a sow, as evident from uniform depth along chromosome X

(Supplementary Figure S4). The filtering strategy applied (see Materials and methods) allowed us to retrieve the same mutation profile as in modern samples (Supplementary Figure S5). The

numbers of polymorphic sites (that is, sites with different ancient nucleotide and reference genome nucleotide) before and after filtering were 250 622 and 208 628, respectively, that is, an

estimation of post-mortem damage of 16.7%. Note that this is an upper bound because some true SNPs are filtered out if not found in the modern samples; this percentage should be small,

though, as shown in the Materials and methods section. This value was close to that found by PCR in an analysis of a fragment of mitochondrial cytochrome _b_ gene, _MT-CYB_ (13.1%). As for

modern sequences, the numbers of reads were 347 750 566 (Guatemalan Creole), 342 150 846 (Iberian) and 375 306 190 (Spanish wild boar), resulting in average depths 12–13 × after filtering by

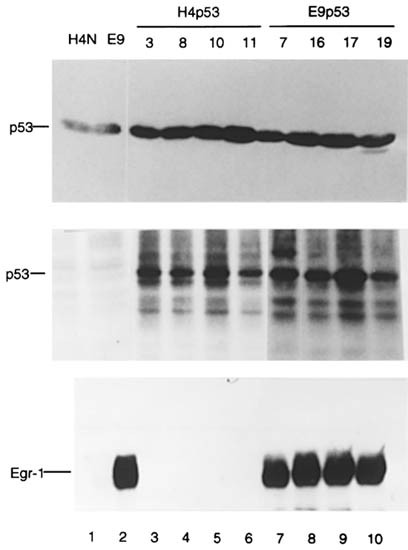

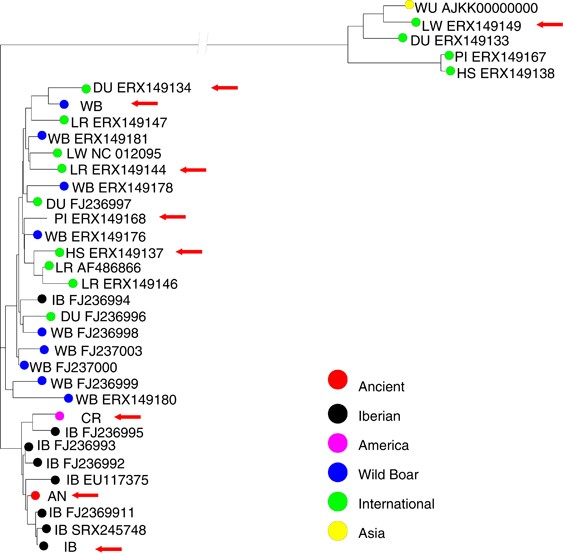

base and map quality; for publicly available genomes, average depths were also similar (10–13 × ; Supplementary Table S2). MITOCHONDRIAL PHYLOGEOGRAPHY Complete ancient mtDNA sequence was

aligned with published sequences and the three modern samples sequenced in this study. Figure 1 shows the NJ tree. As observed with shorter mtDNA fragments like the control region or

cytochrome _b_ (Larson et al. (2005), European wild boar and domestic breed haplotypes were not split into distinct clades but were rather intermixed. Note also that some European domestic

pigs harbor Asian haplotypes, as a result of Chinese introgression. As for the ancient pig, unsurprisingly, it is within the European clade, next to most Iberian haplotypes. Only two

differences separate the ancient pig from the haplotype found in black hairless Iberian Guadyerbas strain and _Lampiño de Guadiana_ Iberian strain (Supplementary Figure S6) and three

differences from a Spanish wild boar (accession FJ237000, _d_=0.0061±0.00024). Note that the Guatemalan Creole haplotype was clearly of Iberian origin as well and was positioned next to

Iberian clade and ancient pig (separated by 3 and 5 differences, respectively). WORLDWIDE CONTEXT INFERRED FROM SNP ARRAYS The large 60k genotyped panel (Supplementary Table S1) makes it

possible to position the ancient sample in a worldwide context. A total of 4090 autosomal SNPs from the 60k array that matched the ancient sample could be retrieved, using the criteria

described in Materials and methods. First, to position the ancient sample and to investigate whether a NE legacy could still be detected, we ran an unsupervised admixture (Alexander et al.,

2009) analysis excluding the Creole pigs, well known to have been admixed. Preliminary analyses suggested _K_=12 as the optimum number of components. Results with this _K_-value (Figure 2)

suggest that the NE component is completely absent from the ancient sample. In fact, the admixture analysis strongly supports a 100% Iberian component to the ancient pig. A principal

component analysis of those SNPs (Figure 3) broadly agrees with the original analysis that included the complete SNP data set from Manunza et al. (2013) and Burgos-Paz et al. (2013), showing

that the 4090 SNPs used here are a representative set—although always subject to SNP ascertainment. Figure 3 was drawn using a randomly sampled allele from each genotype, to match the fact

that only one ancient allele is generally observed. As can be seen in Supplementary Figure S7, sampling has a very small effect in the PC projection. The first principal component explains a

much larger fraction of variance (17.7%) than the second axis (3.7%). First principal component axis is primarily geographical, separating Asian from European populations. The NE wild boars

are closer to European than to Asian pigs, and NE genetic structure grossly coincides with their geographic origin. International breeds, well known to be admixed with Chinese pigs (Giuffra

et al., 2000), are closer to Chinese pigs than are Iberian pigs, not known to have been admixed. Also, all Creole populations show evidence of admixture as found in Burgos-Paz et al.

(2013). In the principal component analysis plot, and in logical agreement with the previous admixture analyses, the ancient sample was located within or nearby the modern Iberian pig

cluster; and it does not show evidence of Asian admixture either. Overall, PC-based distances between Creole and Iberian pigs were very similar to those between Creole and the ancient sample

(Supplementary Figure S8). This again shows that the ancient pig and modern Iberian pig are closely related. As in Burgos-Paz et al. (2013), we found that Yucatan minipigs (originally from

Mexico), Peruvian and some North Argentinean village pigs were the closest populations to both the ancient and the Iberian pigs. GENOME-WIDE ANALYSIS To gain a more faithful view of genetic

relationships, avoiding the SNP ascertainment bias inherent to the 60k array, and to extend the study beyond the mitochondrial lineage, the complete ancient sequence available was combined

with eight additional modern sequences (Supplementary Table S2) that represent the most widespread international pig breeds, and three putative close relatives: Iberian, wild boar and Creole

(Guatemala). After SNP calling and filtering (see Materials and methods), we retained 794 514 autosomal SNPs without any missing value across samples. Figure 4 shows the PCA and a

neighbor-joining tree with distances between samples. The figures show the result of random sampling one of the two alleles in the modern samples; for comparison, other replicates are shown

but the effect of allele sampling was, again, negligible (Supplementary Figure S9). The PCA (Figure 4) has the first axis bounded by the wild boar and Large White, which is the international

breed with the largest Chinese component. The second axis primarily explains divergence with Duroc. In agreement with the array SNPs (Figures 2 and 3) and mtDNA data (Figure 1), the ancient

sample is closest to the Iberian pig and wild boar. We computed autosomal divergence (% of allele differences) between the ancient and the eight modern sequences (Supplementary Table S4),

which again shows that the Iberian pig is the closest sample to the ancient pig, followed by Spanish wild boar, Hampshire and Creole. The length of ancient homozygous stretches (IBS blocks)

shared with the Iberian was the largest, followed at distance by wild boar (Supplementary Table S4). All other samples, including Creole pig, were less similar to the ancient pig. Use of

other publicly available sequences from European wild boar led consistently to similar results (not presented). Mitochondrial and genomic data (Figures 1 and 2, Supplementary Figures S6, S7

and Supplementary Table S4) suggest, as the archeological data, that the ancient pig is domestic. The ancient pig, though, is also close to wild boar (Figure 4). To test whether the ancient

pig was actually domestic or wild, we identified 24 positions in the ancient genome that were among the 227 SNPs described by Rubin et al. (2012) as highly differentiated between wild boar

and domestic pigs. For those 27 positions, we also determined the genotypes from a subset of sequenced modern animals and we computed the probability that the sample originates from either

wild boar or domestic (methods). Results (Supplementary Table S5) indicate that the ancient sample is much more likely to be a domestic pig than a wild boar (_P_D=0.72±0.07 vs

_P_W=0.27±0.07). These probabilities are comparable with other domestic pigs (Duroc, Large White, Creole), and somewhat higher than for the Iberian pigs (_P_D=0.65±0.05). As control, note

that wild boar probabilities are reversed (_P_D=0.32±0.03 and _P_W=0.70±0.04). Despite genetic differentiation between wild boar and domestics, wild boar admixture with domestic pigs has

been repeatedly suggested, based both on genetic and historical evidence (Thomas, 2005; Ramírez et al., 2009b). The availability of an animal from five centuries ago may help in resolving

whether this admixture occurred predominantly within the last centuries or predate that time. To investigate this, we applied the D-statistics as implemented in ADMIXtools (Patterson et al.,

2012). The results strongly suggest admixture, both in the ancient and in the modern Iberian pig (Supplementary Table S6). Results were very similar when the wild boar was from Spain,

France or Switzerland. Taken together, the D-statistics suggest gene flow levels of equal intensity between wild boar and both the ancient and Iberian pigs, but that admixture did not occur

frequently enough to wipe out genetic differences between them, as shown by the discriminant SNPs in Supplementary Table S5 and genetic distances in Supplementary Table S4. DISCUSSION

Ancient genomic data are needed to resolve the intricacies in the history of domestic species and to characterize the timing of selective events occurred between domestication and the modern

breeding era. Here we provide the first—to our knowledge—genome data from an ancient domestic pig. It corresponds to a female who lived in the Iberian Peninsula during the last third of the

sixteenth century, before Asian introgression and contemporary to the beginnings of American colonization. More ancient genomes from different epochs and geographic areas will be needed to

validate the results presented here, among them, the timing and extent of admixture with the wild boar. More data will also be needed to clarify the selective events that have occurred from

domestication until the creation of modern breeds and those ongoing as a result of current industrial selection programs. Nevertheless, despite the shallow coverage attained and having a

single individual sequenced, extensive comparison with modern genome sequences and a large genotyped diversity panel allowed us to draw relevant conclusions concerning pig genetic history.

We did not find any evidence of NE wild boar legacy in the ancient sample, although this might be due to the low resolution attained with the SNP array. In contrast, it seems clear that the

sixteenth-century pig was domestic (Figures 1 and 2, Supplementary Tables S4, S5 and Supplementary Figure S6). This is not perhaps unexpected, given that the sample was chosen to avoid

sampling a wild boar as much as possible, based on the sampling site and the size of the bones, but it is reassuring that genetic data confirms this. It agrees as well with the fact that

animal, and specifically pig breeding, was an important activity in Montsoriu castle (Novella, 2013). More importantly, Supplementary Table S5 demonstrates that the diagnostic SNPs

identified by Rubin et al. (2012) using only international pig breeds are also valid on ancient samples, before the onset of modern selection practices. All our data show a close

relationship of the ancient genome to extant Iberian pigs; this is interesting as it demonstrates that the Iberian pigs, at least the traditional strains analyzed here, have not undergone

dramatic modifications in their genomes for centuries. It is also an important result that confirms that Iberian pigs have not been admixed with Asian pigs. The next closest population to

the ancient pig was European wild boar (Supplementary Table S4), indicating a low differentiation between wild boar and Iberian pigs and in agreement with previous works Ramírez et al.

(2009b). The D-statistics (Supplementary Table S6) in fact suggests that admixture between wild boar and both ancient and Iberian pigs has occurred, as also proposed by several authors

(Ramírez et al., 2009b; Van Asch et al., 2012) and that admixture levels were very similar in either the Iberian or the ancient sample. On the basis of the similar D-statistics when using IB

or ancient samples (Supplementary Table S6), it can be tentatively hypothesized that the gene flow between wild boar and domestics occurred primarily before the sixteenth century, rather

than during modern ages, but more coverage is needed to resolve this definitely. We should remark, though, that the degree of admixture was not enough to wipe out differences between wild

and domestic pigs. For instance, we found a larger number of haplotype blocks shared between ancient and Iberian than between ancient and wild boar (1351 vs 865, Supplementary Table S4, see

also Supplementary Table S5). Nevertheless, a somewhat surprising result is the high similarity between the ancient genome and the wild boar genome when using all sequence data (Figure 4) as

compared with its somewhat smaller similarity inferred from array data (Figure 3). It can be hypothesized that the genetic similarity between the ancient pig and a Spanish wild boar is due

to local processes (say intense local admixture in Spain) rather than to domestication. To investigate this matter, we carried out a new PCA with sequence of four wild boars from four

European countries, four Iberian pigs and four Duroc pigs. Results (Supplementary Figure S10) are concordant with those in Figure 4: the ancient sample is positioned between WB and IB, and

there is very low variability within European WB compared to variability between populations. Therefore, the pattern observed is not due to a specific event having occurred in Spain, but

rather reflects a general process of domestication in Europe. These data, as well as our previous work in Ojeda et al. (2011) and the recent paper by Bosse et al. (2014), also suggest that

most of divergence between the ancient pig and modern international pig breeds (say Duroc or Large White) is caused by Asian introgression rather than by domestication itself, because the

divergence among modern Iberian pigs, wild boar and the ancient sample is much smaller than with breeds known to have been admixed with Asian germplasm. Iberian pig is not a uniform

population (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S9), it is made up of several varieties that differ in coat color or hair density. Among Iberian strains, the ancient sample seems directly

related to extant black hairless strains, as follows from the mtDNA haplotype (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S6). Modern Iberian pigs are red or black, but never white. Unsurprisingly,

we found no evidence of the _KIT_ gene (ENSSSCG00000008842) duplication, which is responsible for the white color (Giuffra et al., 2002): in the ancient sample, 5126 bp within the bounds of

_KIT_ gene (SSC8: 43 550 236–43 602 062) were covered with average depth 1.02, almost identical to the average depth in that chromosome (1.07). In contrast, depth in the _KIT_ gene for the

Large White sample, known to carry the duplicated gene, was 20.02 or about twice the average depth along SSC8 (10.41), whereas depth in the Iberian sample, which has a single copy of the

gene, was the same in the _KIT_ gene and along SSC8, 11.97 and 13.03. Supplementary Figure S11 shows the distinct patterns in an individual with and without the duplication, and the plots

strongly suggest that the ancient sample lacks the duplication. Furthermore, all historical depictions from Iberian pigs in the epoch show predominantly black pigs and none white, whereas

paintings from Northern Europe does show spotted or white pigs (Martín-Rivas, 2012). Unfortunately, there were no reads aligned to the _MC1R_ gene in the ancient pig, which would have

allowed us to confirm either red or black coat color, but all evidence points to a non-white individual. Pig introduction from Spain in the Americas started with Columbus’ second trip, in

1493 (Rodero et al., 1992; Zadik, 2005), and pigs adapted quickly to the new environments (Elliot, 2007). Following our previous work (Burgos-Paz et al., 2013), a matter of historical

interest is to disclose whether the current American Creole pigs are more related to the ancient sample than to the modern Iberian pigs. The availability of a contemporary pig from the

initial American colonization (sixteenth century) period should help to illuminate this issue. Our genotypic (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure S7) and sequence data (Figure 4, Supplementary

Table S4) show that the ancient pig and the modern Iberian pigs are equally close to American Creole pigs. This confirms, as pointed out in Burgos-Paz et al. (2013), that American Creole

pigs have lost much of its primigenious Iberian origin by admixture with other breeds, and not because Iberian pigs originally introduced in the Americas were very different from those

living in Spain today. It is likely that many more livestock ancient genomes will be published in the near future, providing a diachronic view of main demographic and selective events. Our

work, nevertheless, illustrates one of the main problems of aDNA studies: the low retrieval of endogenous DNA reads, specially in temperate climate conditions, which is normally in the order

of 1% for most of the samples. However, these paleogenomic approaches are still more efficient, in terms of the amount of sequence data generated, than PCR-based strategies. DATA ARCHIVING

Ancient, Iberian, Spanish wild boar and Guatemalan reads have been submitted to SRA (accession SRP044261), aligned mitochondrial fasta file, plink files with genotypic data have been

deposited in Dryad (doi:10.5061/dryad.sd784). ACCESSION CODES ACCESSIONS GENBANK/EMBL/DDBJ * AF486866 * EU117375 * FJ236991 * FJ236992 * FJ236993 * FJ236994 * FJ236995 * FJ236996 * FJ236997

* FJ236998 * FJ236999 * FJ237000 * FJ237003 * NC_012095 REFERENCES * Albarella U . (1997). Size, power, wool and veal: zooarchaeological evidence for late medieval innovations. In: De Boe G,

Verhaegue F, (eds) _Environment and Subsistence in Medieval Europe, IAP Rapporten_ VOL 9, Instituut voor het Archeologisch Patrimonium: Zellik, The Netherlands. pp 19–30. Google Scholar *

Albarella U, Dobney K, Rowley-Conwy P . (2009). Size and shape of the Eurasian wild boar (_Sus scrofa_), with a view to the reconstruction of its Holocene history. _Environ Archaeol_ 14:

103–136. Article Google Scholar * Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K . (2009). Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. _Genome Res_ 19: 1655–1664. Article CAS

Google Scholar * Alves E, Ovilo C, Rodríguez MC, Silió L . (2003). Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation and phylogenetic relationships among Iberian pigs and other domestic and wild pig

populations. _Anim Genet_ 34: 319–324. Article CAS Google Scholar * Bandelt HJ, Macaulay V, Richards M . (2000). Median networks: speedy construction and greedy reduction, one simulation,

and two case studies from human mtDNA. _Mol Phylogenet Evol_ 16: 8–28. Article CAS Google Scholar * Bosse M, Megens H-J, Madsen O, Frantz LaF, Paudel Y, Crooijmans RP _et al_. (2014).

Untangling the hybrid nature of modern pig genomes: a mosaic derived from biogeographically distinct and highly divergent _Sus scrofa_ populations. _Mol Ecol_ 23: 4089–4102. Article Google

Scholar * Burgos-Paz W, Souza Ca, Megens HJ, Ramayo-Caldas Y, Melo M, Lemús-Flores C _et al_. (2013). Porcine colonization of the Americas: a 60k SNP story. _Heredity_ 110: 321–330. Article

CAS Google Scholar * Conolly J, Colledge S, Dobney K, Vigne J-D, Peters J, Stopp B _et al_. (2011). Meta-analysis of zooarchaeological data from SW Asia and SE Europe provides insight

into the origins and spread of animal husbandry. _J Archaeol Sci_ 38: 538–545. Article Google Scholar * Edgar RC . (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high

throughput. _Nucleic Acids Res_ 32: 1792–1797. Article CAS Google Scholar * Elliot J . (2007) _Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492–1830_. Yale University

Press: New Haven, CT, USA. Google Scholar * Ervynck A, Lentacker A, Müldner G, Richards M, Dobney K . (2007). An investigation into the transition from forest dwelling pigs to farm animals

in Medieval Flanders, Belgium. In: Albarella U, Dobney KM, Ervynvk PR-C A, (eds) _Pigs and Humans:10000 years of interaction_. Oxford University Press: Oxford. pp 171–196. Google Scholar *

Esteve-Codina A, Paudel Y, Ferretti L, Raineri E, Megens H-J, Silió L _et al_. (2013). Dissecting structural and nucleotide genome-wide variation in inbred Iberian pigs. _BMC Genomics_ 14:

148. Article CAS Google Scholar * Fang X, Mou Y, Huang Z, Li Y, Han L, Zhang Y _et al_. (2012). The sequence and analysis of a Chinese pig genome. _Gigascience_ 1: 16. Article CAS

Google Scholar * Font G, Llorens J, Mateu J, Pujadas S . (2010). L’abandonament del castell de Montsoriu. Segles XVI-XVII. _Monogr del Montseny_ 18: 207–215. Google Scholar * Font G, Mateu

J, Pujadas S, Tura J . (2008). Síntesi històrica del castell de Montsoriu. _Monogr del Montseny_ 23: 109–134. Google Scholar * Font G, Mateu J, Tura J . (2007). Memòria excavacions

arqueològiques castell de Montsoriu, Arbúcies—Sant Feliu de Buillalleu, la Selva Campanya 2007. _Museu Etnológic del Montseny: La Gabella d’Arbúcies_. * García-Garcerà M, Gigli E,

Sanchez-Quinto F, Ramirez O, Calafell F, Civit S _et al_. (2011). Fragmentation of contaminant and endogenous DNA in ancient samples determined by shotgun sequencing; prospects for human

palaeogenomics. _PLoS ONE_ 6: e24161. Article Google Scholar * Giuffra E, Kijas JM, Amarger V, Carlborg O, Jeon JT, Andersson L . (2000). The origin of the domestic pig: independent

domestication and subsequent introgression. _Genetics_ 154: 1785–1791. CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar * Giuffra E, Törnsten A, Marklund S, Bongcam-Rudloff E, Chardon P, Kijas

JMH _et al_. (2002). A large duplication associated with dominant white color in pigs originated by homologous recombination between LINE elements flanking KIT. _Mamm Genome_ 13: 569–577.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW, Maricic T, Stenzel U, Kircher M _et al_. (2010). A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. _Science_ 328: 710–722. Article

CAS Google Scholar * Groenen MaM, Archibald AL, Uenishi H, Tuggle CK, Takeuchi Y, Rothschild MF _et al_. (2012). Analyses of pig genomes provide insight into porcine demography and

evolution. _Nature_ 491: 393–398. Article CAS Google Scholar * Huson DH, Mitra S, Ruscheweyh H-J, Weber N, Schuster SC . (2011). Integrative analysis of environmental sequences using

MEGAN4. _Genome Res_ 21: 1552–1560. Article CAS Google Scholar * Krause J, Dear PH, Pollack JL, Slatkin M, Spriggs H, Barnes I _et al_. (2006). Multiplex amplification of the mammoth

mitochondrial genome and the evolution of Elephantidae. _Nature_ 439: 724–727. Article CAS Google Scholar * Krause-Kyora B, Makarewicz C, Evin A, Flink LG, Dobney K, Larson G _et al_.

(2013). Use of domesticated pigs by Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in northwestern Europe. _Nat Commun_ 4: 1–7. Article Google Scholar * Lalueza-Fox C, Römpler H, Caramelli D, Stäubert C,

Catalano G, Hughes D _et al_. (2007). A melanocortin 1 receptor allele suggests varying pigmentation among Neanderthals. _Science_ 318: 1453–1455. Article CAS Google Scholar * Larson G,

Albarella U, Dobney K, Rowley-conwy P, Tagliacozzo A, Manaseryan N _et al_. (2007). Ancient DNA, pig domestication, and the spread of the Neolithic into Europe. _Proc Natl Acad Sci USA_ 104:

15276–15281. Article Google Scholar * Larson G, Dobney K, Albarella U, Fang M, Matisoo-Smith E, Robins J _et al_. (2005). Worldwide phylogeography of wild boar reveals multiple centers of

pig domestication. _Science_ 307: 1618–1621. Article CAS Google Scholar * Li H, Durbin R . (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. _Bioinformatics_

25: 1754–1760. Article CAS Google Scholar * Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N _et al_. (2009). The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. _Bioinformatics_ 25:

2078–2079. Article Google Scholar * Lindgreen S . (2012). AdapterRemoval: easy cleaning of next-generation sequencing reads. _BMC Res Notes_ 5: 337. Article Google Scholar * MacKinnon M

. (2004). Production and consumption of animals in Roman Italy: integrating the zooarchaeological and textual evidence. _J Rom Archaeol Supplement_. Portsmouth,: RI, USA. pp 264. Google

Scholar * Manunza A, Zidi A, Yeghoyan S, Balteanu VA, Carsai TC, Scherbakov O _et al_. (2013). A high throughput genotyping approach reveals distinctive autosomal genetic signatures for

European and Near Eastern wild boar. _PLoS ONE_ 8: e55891. Article CAS Google Scholar * Martín-Rivas S . (2012). El cerdo ibérico y el Arte en España. _Universidad Internacional de

Andalucía_. * McVean G . (2009). A genealogical interpretation of principal components analysis. _PLoS Genet_ 5: e1000686. Article Google Scholar * Meiri M, Huchon D, Bar-Oz G, Boaretto E,

Horwitz LK, Maeir AM _et al_. (2013). Ancient DNA and population turnover in southern levantine pigs- signature of the sea peoples migration? _Sci Rep_ 3: 3035. Article Google Scholar *

Novella V . (2013). La dieta avícola en el siglo XVI: conservación y consumo de aves en el Castillo de Montsoriu (Montseny). In: Lopez B, (eds) _LA producción de alimentos. Arqueología,

historia y futuro de la dieta mediterranea_. Universidad de Mazarrón: Murcia. pp 109–119. Google Scholar * Ojeda a, Ramos-Onsins SE, Marletta D, Huang LS, Folch JM, Pérez-Enciso M . (2011).

Evolutionary study of a potential selection target region in the pig. _Heredity_ 106: 330–338. Article CAS Google Scholar * Olalde I, Allentoft ME, Sánchez-Quinto F, Santpere G, Chiang

CWK, DeGiorgio M _et al_. (2014). Derived immune and ancestral pigmentation alleles in a 7,000-year-old Mesolithic European. _Nature_ 507: 225–228. Article CAS Google Scholar * Ottoni C,

Flink LG, Evin A, Geörg C, De Cupere B, Van Neer W _et al_. (2013). Pig domestication and human-mediated dispersal in western Eurasia revealed through ancient DNA and geometric

morphometrics. _Mol Biol Evol_ 30: 824–832. Article CAS Google Scholar * Patterson N, Moorjani P, Luo Y, Mallick S, Rohland N, Zhan Y _et al_. (2012). Ancient admixture in human history.

_Genetics_ 192: 1065–1093. Article Google Scholar * Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D _et al_. (2007). PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and

population-based linkage analyses. _Am J Hum Genet_ 81: 559–575. Article CAS Google Scholar * R Core Team. (2014) _R: A language and environment for statistical computing_. Foundation for

Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. * R Development Core Team. (2011) _R: A language and environment for statistical computing_. Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna. * Ramírez

O, Gigli E, Bover P, Alcover JA, Bertranpetit J, Castresana J _et al_. (2009a). Paleogenomics in a temperate environment: shotgun sequencing from an extinct Mediterranean caprine. _PLoS ONE_

4: e5670. Article Google Scholar * Ramírez O, Ojeda A, Tomàs A, Gallardo D, Huang LS, Folch JM _et al_. (2009b). Integrating Y-chromosome, mitochondrial, and autosomal data to analyze the

origin of pig breeds. _Mol Biol Evol_ 26: 2061–2072. Article Google Scholar * Rasmussen M, Anzick SL, Waters MR, Skoglund P, DeGiorgio M, Stafford TW _et al_. (2014). The genome of a Late

Pleistocene human from a Clovis burial site in western Montana. _Nature_ 506: 225–229. Article CAS Google Scholar * Rasmussen M, Guo X, Wang Y, Lohmueller KE, Rasmussen S, Albrechtsen A

_et al_. (2011). An Aboriginal Australian genome reveals separate human dispersals into Asia. _Science_ 334: 94–98. Article CAS Google Scholar * Rodero A, Delgado JV, Rodero E . (1992).

Primitive Anadalusian livestock and their implications in the discovery of America. _Zootecnia_ 41: 384–400. Google Scholar * Rubin C-J, Megens H-J, Martinez Barrio A, Maqbool K, Sayyab S,

Schwochow D _et al_. (2012). Strong signatures of selection in the domestic pig genome. _Proc Natl Acad Sci USA_ 109: 19529–19536. Article CAS Google Scholar * Sánchez-Quinto F, Schroeder

H, Ramirez O, Avila-Arcos MC, Pybus M, Olalde I _et al_. (2012). Genomic affinities of two 7,000-year-old Iberian hunter-gatherers. _Curr Biol_ 22: 1494–1499. Article Google Scholar *

Schubert M, Ginolhac A, Lindgreen S, Thompson JF, Al-Rasheid KaS, Willerslev E _et al_. (2012). Improving ancient DNA read mapping against modern reference genomes. _BMC Genomics_ 13: 178.

Article CAS Google Scholar * Silver A . (1969). The ageing of domestic animals. In: Brothwell DR, Higgs ES, (eds) _Science in Archaeology_. Thames and Hudson: London. pp 283–302. Google

Scholar * Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S . (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum

parsimony methods. _Mol Bol Evol_ 28: 2731–2739. Article CAS Google Scholar * Thalmann O, Shapiro B, Cui P, Schuenemann VJ, Sawyer SK, Greenfield DL _et al_. (2013). Complete

mitochondrial genomes of ancient canids suggest a European origin of domestic dogs. _Science_ 342: 871–874. Article CAS Google Scholar * Thomas R . (2005) _Animals, Economy and Status:

the Integration of Zooarchaeological and Historical Evidence in the Study of Dudley Castle, West Midlands (c.1100-1750)_. Archaeopre. BAR British Series 392: Oxford. Google Scholar * Thomas

R, Holmes M, Morris J . (2013). “So bigge as bigge may be”: tracking size and shape change in domestic livestock in London (AD 1220–1900). _J Archaeol Sci_ 40: 3309–3325. Article Google

Scholar * Toro Ma, Rodrigañez J, Silio L, Rodriguez C . (2008). Genealogical analysis of a closed herd of black hairless Iberian pigs. _Conserv Biol_ 14: 1843–1851. Article Google Scholar

* Van Asch B, Pereira F, Santos LS, Carneiro J, Santos N, Amorim a . (2012). Mitochondrial lineages reveal intense gene flow between Iberian wild boars and South Iberian pig breeds. _Anim

Genet_ 43: 35–41. Article CAS Google Scholar * Von Den Driesch A . (1976) _A guide to the Measurement of Animal Bones from Archaeological Sites_. Harvard University Press: Havard. Google

Scholar * Wall JD, Slatkin M . (2012). Paleopopulation genetics. _Annu Rev Genet_ 46: 635–649. Article CAS Google Scholar * Wang K, Li M, Bucan M . (2007). Pathway-based approaches for

analysis of genomewide association studies. _Am J Hum Genet_ 81: 1278–1283. Article CAS Google Scholar * Zadik B . (2005) _The Iberian Pig in Spain and the Americas at the time of

Columbus_. University of California. Google Scholar Download references ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank J Tura, J Mateu, G Font, S Pujadas, JM Llorens and _Museu Etnològic del Montseny_ for the

ancient sample, A. Luarca and E. Caal for providing the Guatemalan Creole sample, L. Silió and M.C. Rodríguez for the Iberian sample, M. Amills for genotype data in Manunza et al. (2013),

L.A. Frantz for discussions on the D statistic, and D.A.Hughes for proof correcting the English. Archeological excavation funded by _Direcció General d'Arxius, Biblioteques, Museus I

Patrimoni_ and _Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya_. This study was funded by 2010ACOM00030 (AGAUR) to MS, FEDER and BFU2012-34157 grant (Spain) to CLF, Consolider CSD2007-00036 ‘Centre for

Research in Agrigenomics’ and AGL2010-14822 grants (Spain) to MPE. OR is a postdoctoral Researcher from the JAEDOC program cofounded by ESF, EB is recipient of a FPI grant from ministry of

Research (Spain), IO of a predoctoral fellowship from the Basque Government (DEUI, Spain), WBP is funded by COLCIENCIAS (_Francisco José de Caldas_ fellowship 497/2009, Colombia). AUTHOR

INFORMATION Author notes * O Ramírez and W Burgos-Paz: These authors contributed equally to this work. AUTHORS AND AFFILIATIONS * Institut de Biologia Evolutiva (CSIC-Universitat Pompeu

Fabra), PRBB, Barcelona, Spain O Ramírez, I Olalde, G Santpere & C Lalueza-Fox * Centre for Research in Agricultural Genomics (CRAG), CSIC-IRTA-UAB-UB Consortium, Bellaterra, Spain W

Burgos-Paz, E Casas, M Ballester, E Bianco & M Pérez-Enciso * Departament de Ciència Animal i dels Aliments, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain W Burgos-Paz, M

Ballester, E Bianco & M Pérez-Enciso * Departament de Prehistòria, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain V Novella & M Saña * Centro Nacional de Análisis Genómico

(CNAG), PCB, Barcelona, Spain M Gut * Institut Català de Recerca i Estudis Avançats (ICREA), Carrer de Lluís Companys 23, Barcelona, Spain M Pérez-Enciso Authors * O Ramírez View author

publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * W Burgos-Paz View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * E Casas View

author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * M Ballester View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * E Bianco

View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * I Olalde View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * G

Santpere View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * V Novella View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

* M Gut View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * C Lalueza-Fox View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google

Scholar * M Saña View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar * M Pérez-Enciso View author publications You can also search for this author inPubMed

Google Scholar CORRESPONDING AUTHOR Correspondence to M Pérez-Enciso. ETHICS DECLARATIONS COMPETING INTERESTS The authors declare no conflict of interest. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Heredity website SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION (DOC 4035 KB) RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license,

unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce

the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Reprints and permissions ABOUT THIS ARTICLE CITE THIS ARTICLE Ramírez, O., Burgos-Paz,

W., Casas, E. _et al._ Genome data from a sixteenth century pig illuminate modern breed relationships. _Heredity_ 114, 175–184 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2014.81 Download citation *

Received: 04 March 2014 * Revised: 09 July 2014 * Accepted: 06 August 2014 * Published: 10 September 2014 * Issue Date: February 2015 * DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2014.81 SHARE THIS

ARTICLE Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content: Get shareable link Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article. Copy to clipboard

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative