- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

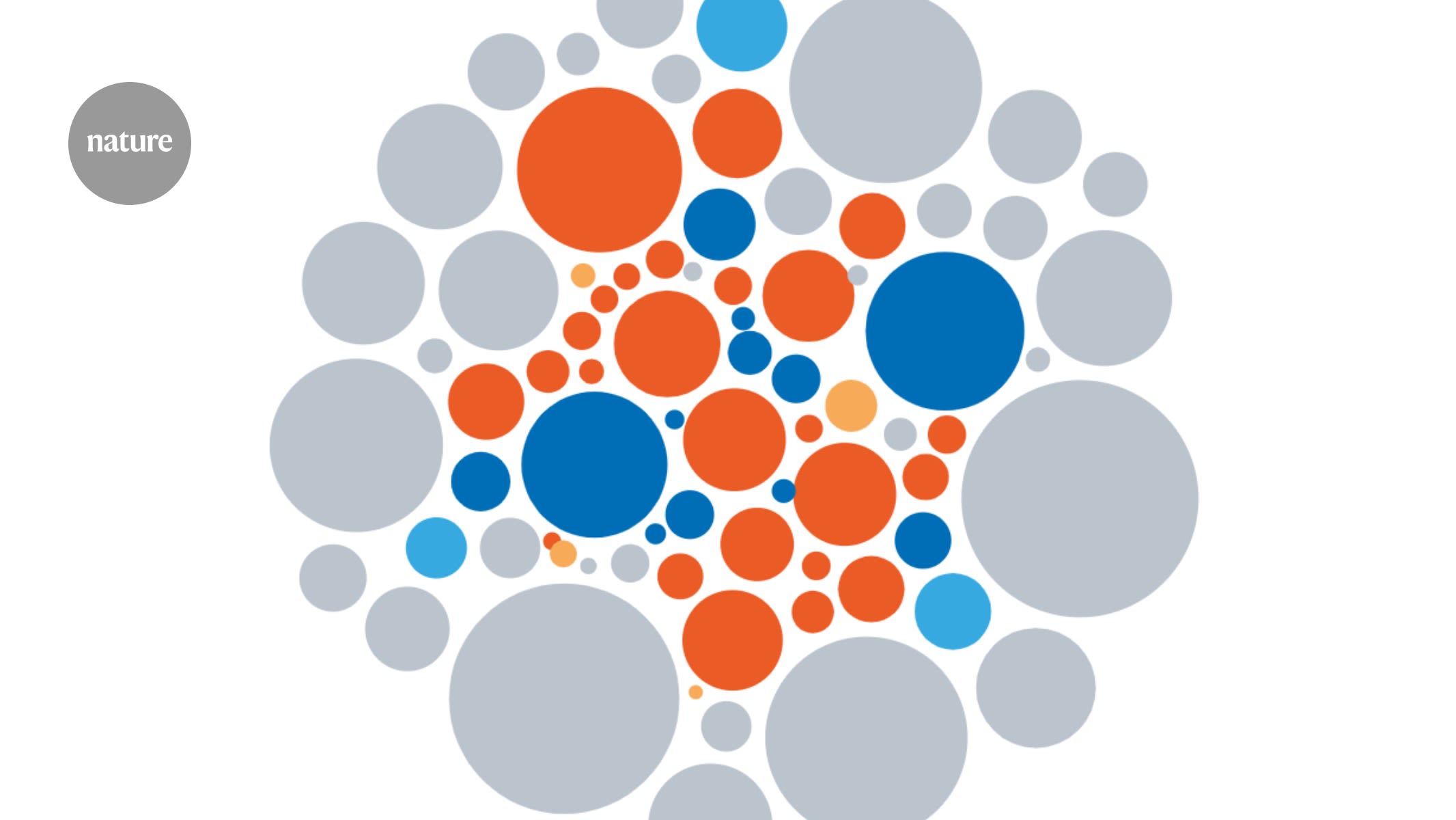

Source: Ref. 1 These results come from the work of US applied mathematician Arthur Mirin, an independent researcher who initially published the analysis1 in 2021. The data shown here are

from his updated analysis of the latest NIH information on funding and burden. The overall pattern remains the same. The 2021 analysis “demonstrates that the funding of research for women is

not aligned with burdens of disease”, says Sarah Temkin, associate director for clinical research at the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health in Bethesda, Maryland. Neuroscientist Liisa

Galea, at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Canada, who has published on female representation in science, is not surprised by the findings of Mirin’s study on funding

for women’s health. “Unfortunately it is really undervalued, understudied.” In an e-mail to _Nature_, the NIH also said that it takes into account considerations beyond the burden of disease

when making funding decisions, for example for urgent research that might mitigate an outbreak of infectious disease. Mirin is not the only one to make such observations. A smaller

analysis2 of cancer funding, using data from the US National Cancer Institute over the 11 years from 2007 to 2017, showed that gynaecological cancers receive much less support than do other

cancers when accounting for lethality (years of life lost for each new diagnosis). In a selection of 19 cancers, ovarian cancer ranks 5th for lethality, but 12th in terms of its

funding-to-lethality ratio. Cervical cancer followed a similar pattern. For many gynaecological cancers, the ratio of funding to mortality dropped during the 11-year period. Although other

public funding agencies outside the United States don’t provide such granular detail, one team of researchers looked at almost 9,000 grants3 awarded by the Canadian Institutes of Health

Research, the country’s main funder of such research, from 2009 to 2020. They found that 5.9% of grants looked at female-specific outcomes, although the grants were worth more on average in

2020 than in 2009. The UK Medical Research Council (MRC) provided _Nature_ with figures on its funding for women’s health, which includes research on preterm birth and perinatal health, and

long-term studies such as the Million Women Study, which investigates the effects of diet, smoking and other factors on disorders including cancer and heart disease. The funder spent £96

million (US$119 million) on this area in the 5 years from 2014. That was roughly equivalent to its spending on cardiovascular disease alone in the same period (the MRC spends about £325

million a year on health research overall). Galea, who studies depression and Alzheimer’s disease, among other disorders, says women’s health funding should cover more than just

female-specific conditions. “Every single organ in our body is affected by our sex,” she says. “It affects every part of our health.” HISTORICAL BIAS Women have been historically

under-represented in other parts of the medical research pipeline, such as clinical trials. The same is true for female animals in basic research. “It takes a long time to recover from the

gaps in the evidence base that resulted from exclusion,” says Temkin. Work to rectify the bias in clinical research is paying off in some places: by 2014, about half of all participants in

clinical trials funded by the NIH were women. But even so, women are not necessarily included in proportions that match the prevalence or burden of disease. For instance, in the United

States, women comprised 42.9% of participants in oncology clinical trials between 2000 and 2020, but experienced 46.5% of the burden4. In neurology and immunology, too, women were

under-represented. In some conditions, such as musculoskeletal disease and trauma, they were over-represented.