- Select a language for the TTS:

- UK English Female

- UK English Male

- US English Female

- US English Male

- Australian Female

- Australian Male

- Language selected: (auto detect) - EN

Play all audios:

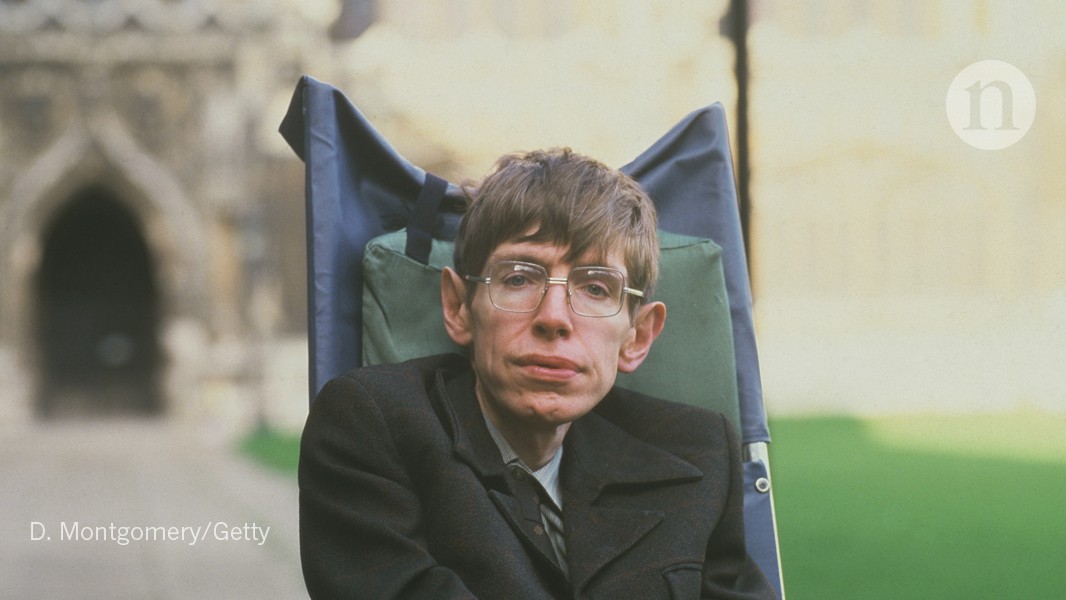

When Stephen Hawking was diagnosed with motor-neuron disease at the age of 21, it wasn’t clear that he would finish his PhD. Against all expectations, he lived on for 55 years, becoming one

of the world’s most celebrated scientists. Hawking, who died on 14 March 2018, was born in Oxford, UK, in 1942 to a medical-researcher father and a philosophy-graduate mother. After

attending St Albans School near London, he earned a first-class degree in physics from the University of Oxford. He began his research career in 1962, enrolling as a graduate student in a

group at the University of Cambridge led by one of the fathers of modern cosmology, Dennis Sciama. The general theory of relativity was at that time undergoing a renaissance, initiated in

part by Roger Penrose at Birkbeck College, London, who had introduced new mathematical techniques. These showed that generic gravitational collapse would lead to singularities — infinities

that signal the need for new physics. Stephen Hawking: A life in science The implications for black holes and the Big Bang were developed by Hawking in a series of papers collated in the

1973 monograph _The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time_ (Cambridge University Press), co-authored with George Ellis, a near-contemporary who had also been a student of Sciama. Especially

important was the realization that the area of black holes’ horizons (‘one-way membranes’ that shroud the singularities, and from within which nothing can escape) could never decrease. The

analogy with entropy — a measure of disorder that likewise can never decrease — was developed further by physicist Jacob Bekenstein. These findings gained Hawking election to the Royal

Society in London in 1974, at the age of 32. By then, he was so frail that both movement and speech were difficult, and most of us suspected that his days in front-line research were

numbered. But in that same year, he came up with his most distinctive contribution to science: Hawking radiation. By linking quantum theory and gravity, Hawking showed that a black hole

would not be completely black, but would radiate with a well-defined temperature that depended inversely on its mass (S. W. Hawking _Nature_ 248, 30–31; 1974). Black-hole entropy was more

than just an analogy. The implication was that the radiation would cause black holes to ‘evaporate’. This process would be unobservably slow, except in ‘mini-holes’ the size of atoms — and

these are thought not to exist. Yet Hawking radiation — and the related issue of whether information that falls into a black hole is lost or is somehow recoverable from the radiation — was a

profound issue, and one that still engenders controversy among theoretical physicists. Indeed, theorist Andrew Strominger at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, said in 2016

that one of Hawking’s papers on the subject (S. W. Hawking _Phys. Rev. D_ 14, 2460–2473; 1976) had caused “more sleepless nights among theoretical physicists than any paper in history”. By

the end of the 1970s, Hawking had been appointed to the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics at Cambridge (former incumbents include Isaac Newton and Paul Dirac); he held the post until he retired

in 2009. During these years, in which his focus shifted to the quantum aspects of the Big Bang, the issue of information loss in black holes continued to challenge him. In 1985, Stephen

underwent a tracheotomy, which removed his already limited powers of speech. He was able to control a cursor on a screen and type out sentences — albeit with increasingly painful slowness

(first with his hand, and eventually only with a cheek muscle). A speech synthesizer processed his words and generated the androidal accent that became his trademark. In this way, he

completed his best-selling book _A Brief History of Time _(Bantam, 1988), which propelled him to celebrity status. ENJOYING OUR LATEST CONTENT? LOGIN OR CREATE AN ACCOUNT TO CONTINUE *

Access the most recent journalism from Nature's award-winning team * Explore the latest features & opinion covering groundbreaking research Access through your institution or Sign

in or create an account Continue with Google Continue with ORCiD

![[withdrawn] near miss with a track worker at llandegai tunnel](https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6051d710d3bf7f0455a6e604/s960_Llandegai_tunnel.jpg)